A Secure and Lightweight ECC-Based Authentication Protocol for Wireless Medical Sensors Networks

Abstract

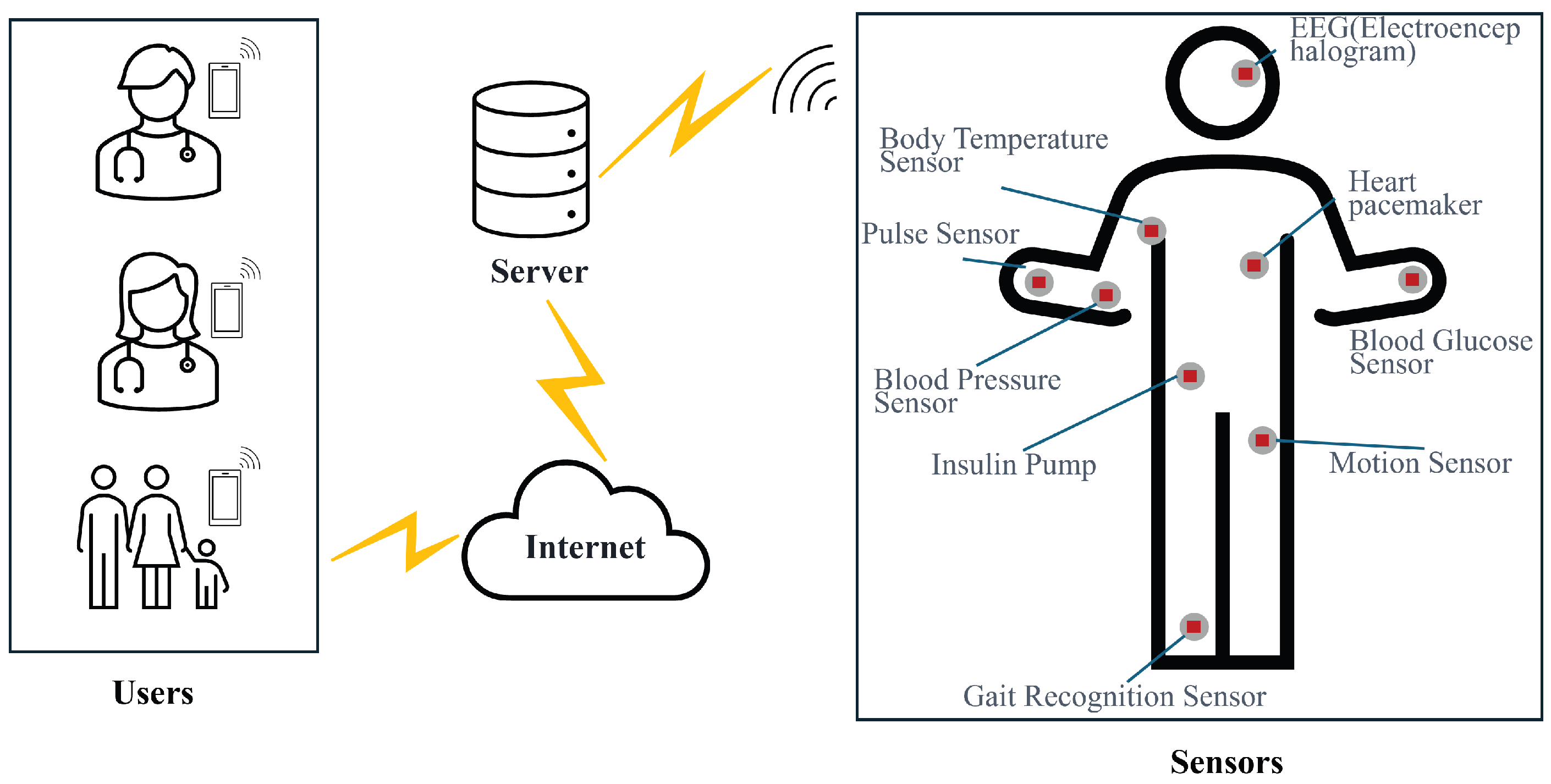

1. Introduction

- We analyze Wang et al.’s ECC-based protocol [18] and identify two major vulnerabilities—ESL and gateway impersonation attacks.

- A robust ECC-based three-factor authentication protocol for WMSNs is proposed. It leverages elliptic curve operations for lightweight key generation and introduces an enhanced adversary model covering insider and ESL attacks.

- The protocol is formally verified under the ROR model and through automated analysis with the ProVerif tool. The findings confirm that the proposed scheme withstands known attacks and satisfies security requirements in WMSNs settings.

- Compared with current protocols, the proposed protocol provides enhanced security features while improving computational and communication efficiency.

2. Related Work

3. Enhanced Attacker Model and Evaluation Criteria

3.1. Attacker Model

- A1:

- The Dolev–Yao model [41] assumes that can intercept, modify, delete, or block messages on public communication channels.

- A2:

- User passwords are typically easy-to-remember strings that follow a Zipf distribution [42]. can exhaustively search all elements of the user identity space and password space offline; and when evaluating non-privacy security, can obtain ’s identity .

- A3:

- When evaluating n factor security (), can obtain any factors. However, all n factors cannot be obtained simultaneously, as this would constitute a trivial attack [43].

- A4:

- can obtain the previous session keys between and [21].

- A5:

- physically captures the medical sensor node with the help of power analysis attacks, and can extract all the stored parameters from the memory [44].

- A6:

- can corrupt , eavesdrop on, and steal the messages received by during any operation.

- A7:

- has a certain ability to guess the random numbers of the protocol participants.

3.2. Evaluation Criteria

4. Review of Wang et al’s Protocol

- 1.

- ESL Attack: In Wang et al.’s scheme, once obtains the session’s temporary information , they can obtain the session key through the following steps.

- (a)

- obtains through a public channel.

- (b)

- extracts from the message.

- (c)

- calculates the session key .

- 2.

- Gateway Impersonation Attack: can generate a replay message that can pass the IoT device verification stage through the following steps:

- (a)

- obtains through the public channel.

- (b)

- generates and computes:, , .

- (c)

- sends to .

- (d)

- After receiving the message, calculates , and verifies .

In this way, the forged message is validated by verification, and successfully performs a gateway impersonation attack.

5. Proposed Protocol

5.1. Initialization Phase

- selects an elliptic curve over the finite field , a large prime number p, and a point as the base point.

- selects as the global private key and computes as the global public key.When using this protocol, the global private key of the server is assumed to remain constant during a specific operational period to ensure consistent authentication for registered users and devices. However, it can be periodically refreshed to improve resistance against key exposure.

- The function is selected as a one-way hash function.

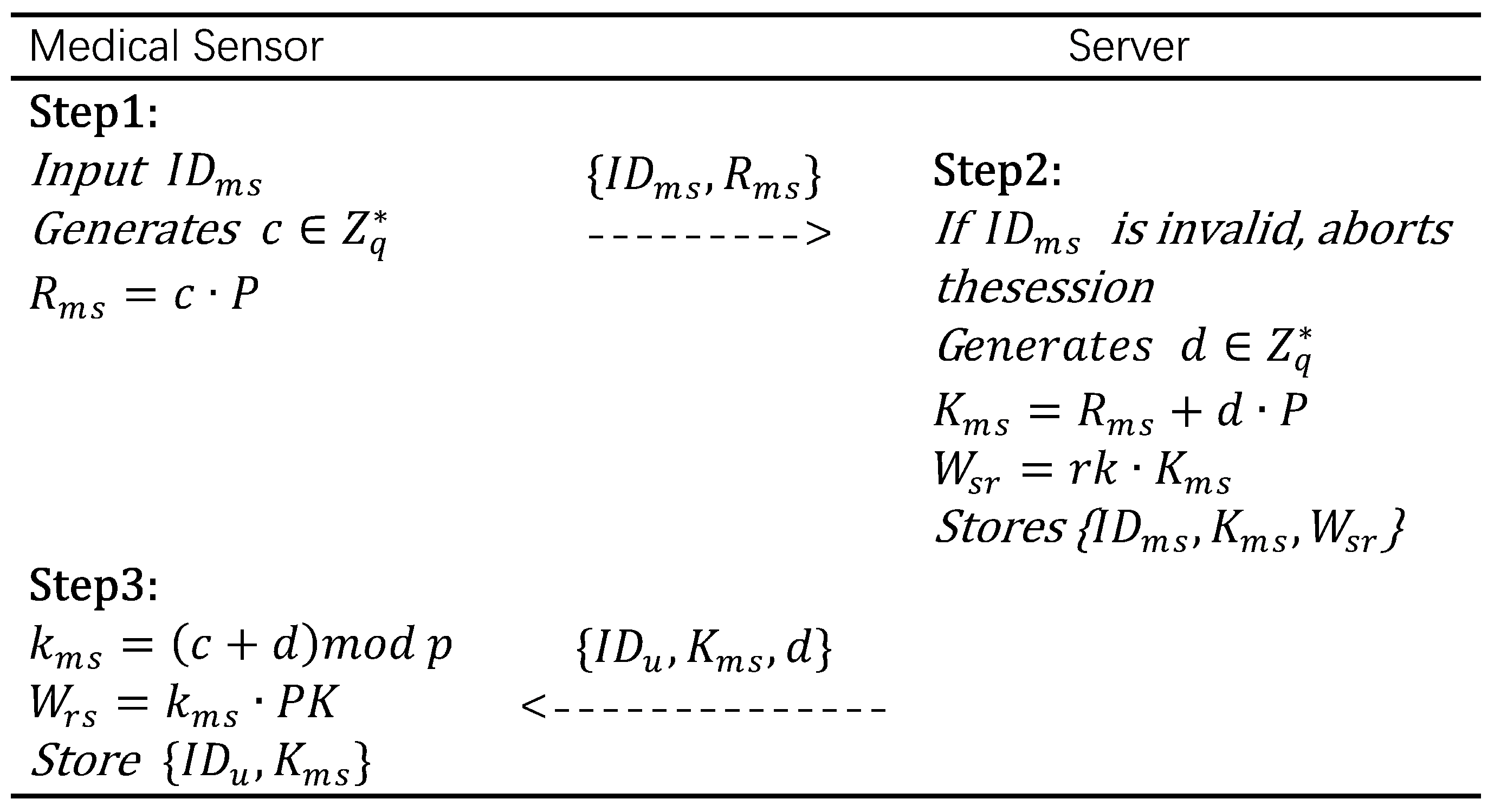

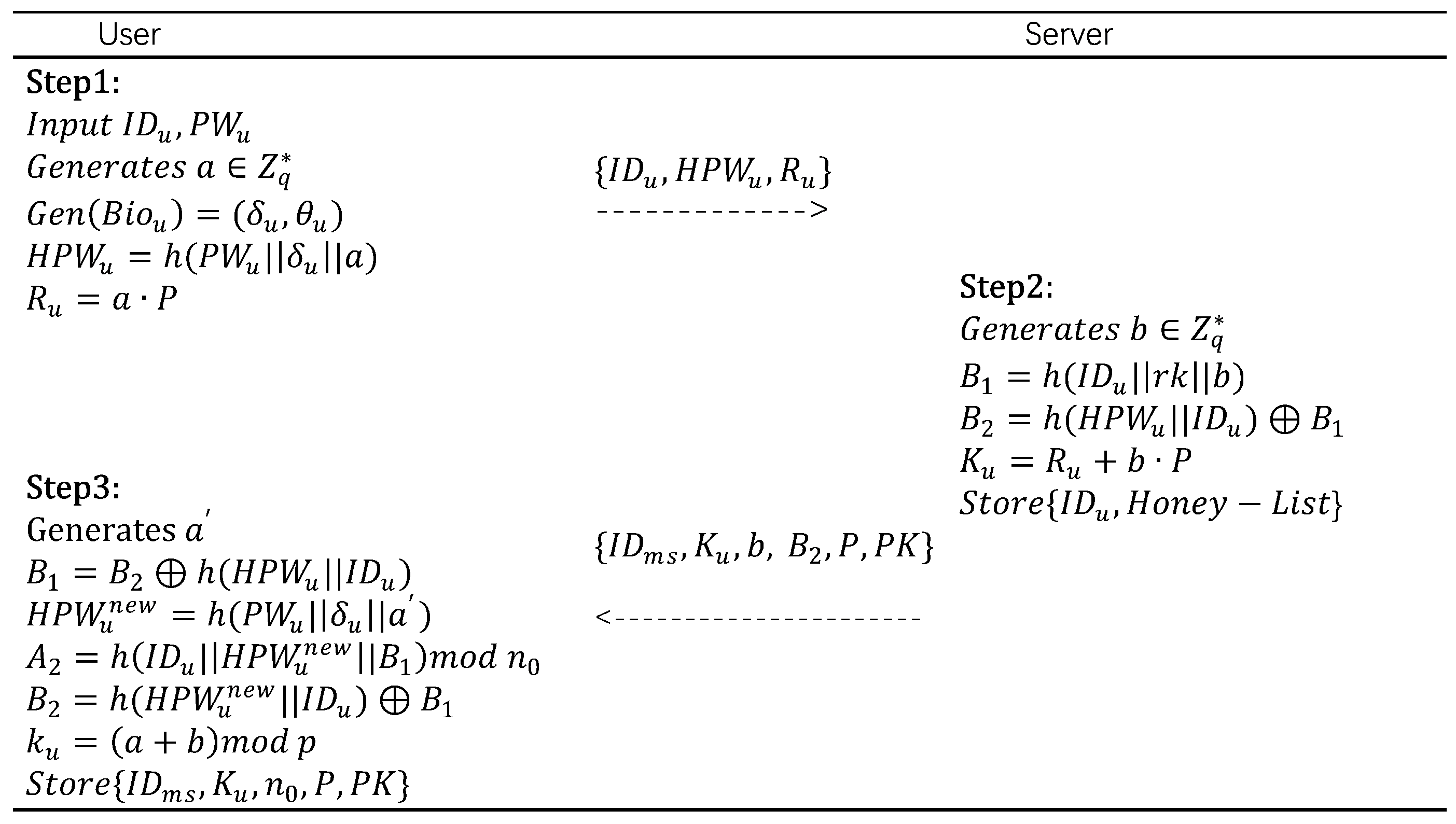

5.2. Registration Phase

- provides its identifier , generates a random number c, calculates , and after the calculation, sends the registration request to .

- After receiving the registration request, first checks whether is valid and does not already exist in the database. If already exists, rejects ’s registration request. Otherwise, generates a random number d, computes , and calculates . stores and then sends to via a secure channel.

- After receiving the message, calculates , computes , and stores .

- inputs , , and , and selects a random number a. It then uses the fuzzy extractor to extract biometric information. and are calculated. Finally, sends a registration request to via a secure channel.

- After receiving the registration request, generates a random number b, and calculates , , and . Here, is used to conceal ’s true identity, is used to transmit , and is ’s public key. After the calculations, stores and securely transmits to via a secure channel.

- After receiving the message, generates a new random number , and calculates , ,, , . Finally, stores .

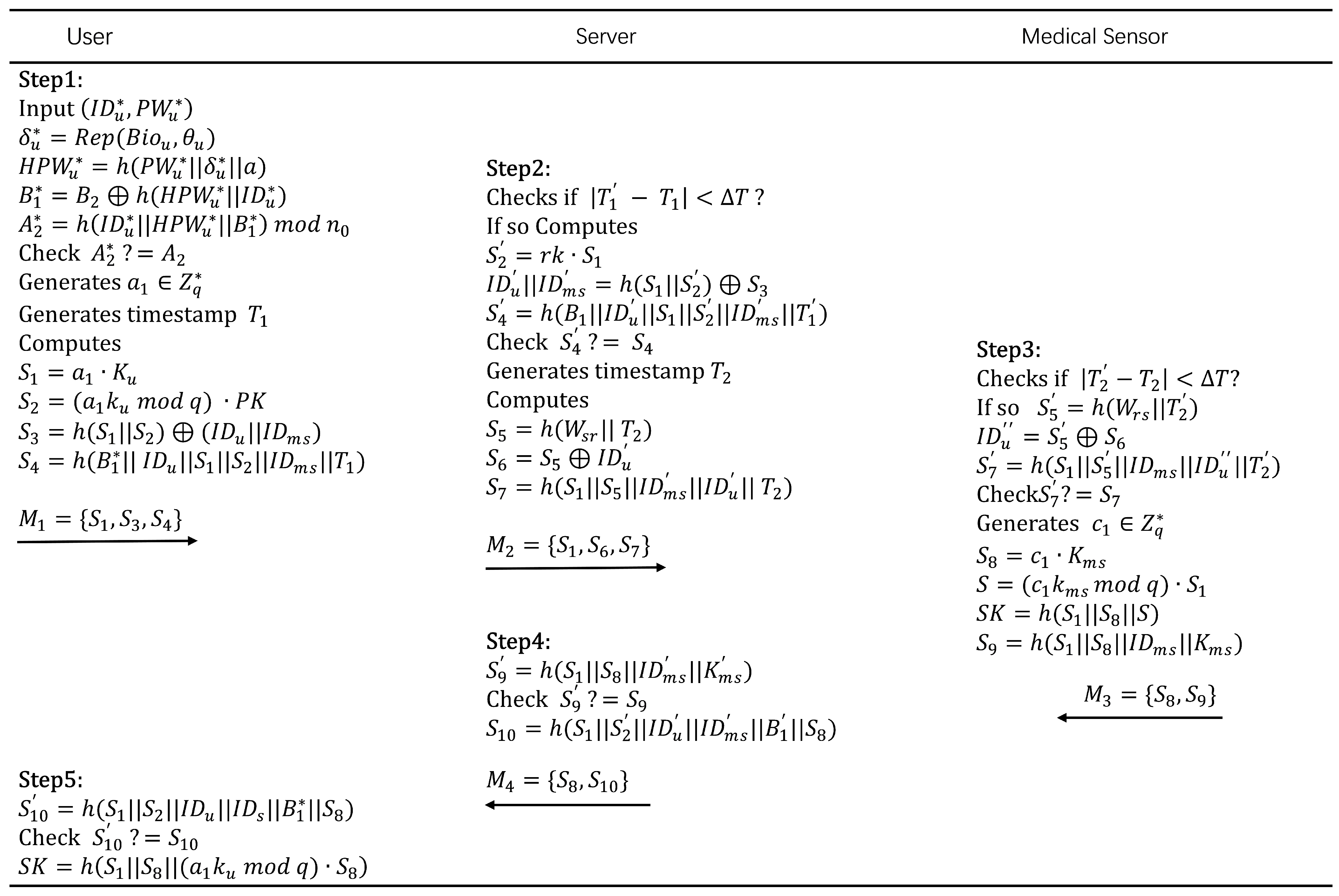

5.3. Authentication Phase

- : .inputs the identity and password , and the biometric data is stored in through the fuzzy extractor. computes , , , . Then, it checks if is equal to to verify ’s legitimacy. If , rejects ’s login request. Otherwise, generates a random number and a timestamp , and calculates , , , . Finally, the login request is sent to .

- : .After receiving the login request, first checks whether holds. If it does, it calculates , , , and verifies . If , terminates the request. Otherwise, it generates a timestamp , calculates , and . Finally, it sends to .

- : .After receiving the message, first checks whether holds. If it does, it calculates , , . Then, it checks whether . If , it terminates the session. Otherwise, it generates a random number , calculates , , , . Finally, it sends to .

- : .After receiving the message, calculates . Then, it checks whether . If , it terminates the session. Otherwise, calculates . Finally, it sends {} to .

- When receives , it calculates . Then, it checks whether . If , the session is terminated. Otherwise, this indicates that has successfully authenticated the . accepts as the session key shared with , and the verification process is successfully completed.

5.4. Password Change Phase

- : .initiates a password update request to and submits

- calculates , , , . If , it rejects the request. Otherwise, it calculates , , . Finally, and are replaced with and , completing the password update.

5.5. Re-Registration Phase

- : .

- : . Upon receiving the re-registration request, first checks the database for the ; if not found, the request is rejected. Otherwise, it selects a new random number , computes , , stores , and finally, it sends to .

- After receiving the response from , selects a new random number , performs the calculations according to the registration phase process, and finally stores .

6. Security Analysis

6.1. Formal Security Analysis

- This query simulates a passive attack, which is used by to obtain the information passed between entities.

- In this query, an active attack is simulated as I, sends a message m to entity , and receives a response from .

- The query simulates the leakage of an established session key by outputting the session key for if it has been created.

- This query simulates ’s ability to corrupt and includes three scenarios:

- For , has the ability to obtain two of the three factors, i.e., output or or .

- For , can obtain the ’s private key and authentication table , i.e., output .

- For , can obtain ’s private key , i.e., output .

- This query aims to define the semantic security of session keys rather than simulate ’s capabilities. It is restricted to “fresh” sessions and is permitted only once. If lacks a session key or the session is not considered “fresh”, it returns ⊥. Otherwise, a random bit b is selected. When , the session key is output; when , a random string of identical length is returned.

- The occurrence of a collision in the output of the hash function, with a probability no greater than ;

- The occurrence of a collision in the random number , with a probability no greater than .

- executes and , meaning can obtain and for and but cannot obtain the ephemeral secret.

- executes and . In this case, can obtain the ephemeral secret of and the long-term secret of .

- executes and . In this case, can obtain the long-term secret of and the ephemeral secret of .

- executes and , meaning can obtain the ephemeral secret of and of .

6.2. Descriptive Security Analysis

- Session Key Agreement: After the mutual authentication is completed, and share a session key , which is used to protect subsequent communication between and . Since the random numbers and are unique for each session, each session key is independent of the others. Therefore, the exposure of the session key in one session does not influence the keys established previously or in the future.

- Mutual Authentication: and achieve mutual authentication through . Specifically, and authenticate each other by verifying whether and hold. Similarly, and achieve mutual authentication by verifying whether and hold. If any of these conditions are not satisfied, the session is terminated. Therefore, the proposed protocol successfully achieves mutual authentication among the three parties.

- Anonymity and Untraceability: The protocol uses the secret parameter , generated through public-key technology, to protect and , with being different for each session. Specifically, the identity identifiers and are not directly transmitted to the . Instead, they are sent in the form of . The only entities that can calculate are and , which holds the private key. cannot obtain and , ensuring the anonymity of and . On the other hand, since and in the login request dynamically change with the random number , cannot track a specific and by eavesdropping on the login request message.

- Resistance Smart Device Loss Attack: Assume the ’s smart device is lost and obtained by , who can retrieve data . On the one hand, if wants to change the password without being noticed by the device, they must construct the correct in order to pass the verification. However, the data retrieved by does not help in computing . On the other hand, if wants to correctly guess the password, they can use and to verify the correctness of their guess. For , even if with biometric features finds identity and password that satisfy , in order to further confirm the password’s correctness, must perform online verification, which will be blocked by the . For , as described in (3), only the real who selects and the that knows the private key can compute . cannot compute , and therefore cannot construct , making it impossible to guess the password’s correctness by comparing and . In summary, our scheme is resilient to such attacks.

- Resistance User Impersonation Attack: impersonates the by forging the login request , where is composed of , as discussed in (4). cannot compute . Therefore, the proposed protocol is capable of defending against user impersonation attacks.

- Resist De-Synchronization Attack: In our protocol, we use random numbers and public-key algorithms to achieve user anonymity and resist replay attacks. Participants do not need to maintain clock synchronization consistency or some temporary certificate-related parameters. Therefore, our scheme can resist de-synchronization attacks.

- Resistance Replay Attack: Suppose has obtained all the login and authentication messages transmitted through a public channel and attempts to replay them to , , and . However, in each session, new random numbers and timestamps , are generated. Once the replayed messages reach and , both entities will verify and . Therefore, the proposed scheme can resist replay attacks.

- Resistance Offline Dictionary Guessing Attack: can retrieve the parameters from and generate an authentication factor using guessed identity and password. By comparing the generated factor with the real one, can verify the accuracy of the guessed password. On the one hand, the password is protected by the technique, and the limits ’s online guessing attempts by recording failed logins. On the other hand, for the authentication factors transmitted over a public channel, in order to conduct an offline dictionary guess attack, must compute . However, only ’s private key and the ’s private key can compute the parameters and . Therefore, the proposed scheme not only resists offline dictionary guess attacks against smart devices but also against offline dictionary guess attacks over public channels.

- Perfect Forward Secrecy: As described in (1), the session key shared between and is associated with ’s private key and the random numbers and . Even if the private key is compromised, cannot use it to decrypt past session records. Since needs to solve the elliptic curve discrete logarithm problem to obtain the parameter S, the future session keys remain secure. Therefore, the proposed scheme achieves perfect forward secrecy.

- Resistance Sensor Node Capture Attack: Assuming captures and uses power analysis attacks to extract the stored parameters , during the authentication phase, sends to , where and . The parameter is generated using the node’s public key and a random number , which is created by the node itself. only has and cannot compute . Moreover, when steals the session key, generating requires calculating and S, where . Since the session key can only be computed by and , the proposed scheme effectively resists node capture attacks.

- Resistance Insider Privilege Attack:

- After successful registration, gains access to the registered smart device and extracts the stored data. However, upon receiving the message from the server, the smart device selects a new random number and updates to a new value , ensuring that . As a result, is unable to obtain the verification parameters needed to guess ’s password.

- The private keys on both the side and side are generated locally rather than on the side, thereby avoiding security threats caused by private key leakage due to the semi-trusted nature of .

- Assuming that can obtain the secret parameters transmitted during the registration phase, namely and , as well as the public channel messages and , is still unable to compute the session key . Therefore, the proposed scheme is resistant to internal privileged attacks.

- Resistance Ephemeral Secret Leakage Attack: The session key , associated with ’s private key and the random numbers and , where , and . Even if gains the random numbers and , they cannot compute the ’s private key . To calculate the session key, must obtain both the random numbers , and the ’s private key , which is an infeasible task. Therefore, even if the two random numbers are leaked, the previous session keys will not be compromised.

- Resistance to Combined and Multi-Adversary Attacks: In addition to insider privileged and ESL attacks, the proposed protocol can also resist more complex threat scenarios involving multiple adversaries or combined attacks. Even if several malicious entities attempt to cooperate, the use of independent session keys and dynamic pseudonyms ensures that compromising one node does not reveal information about others. Furthermore, the mutual authentication and key agreement steps rely on fresh random values and ECC-based computations, preventing coordinated replay or collusion-based attacks.

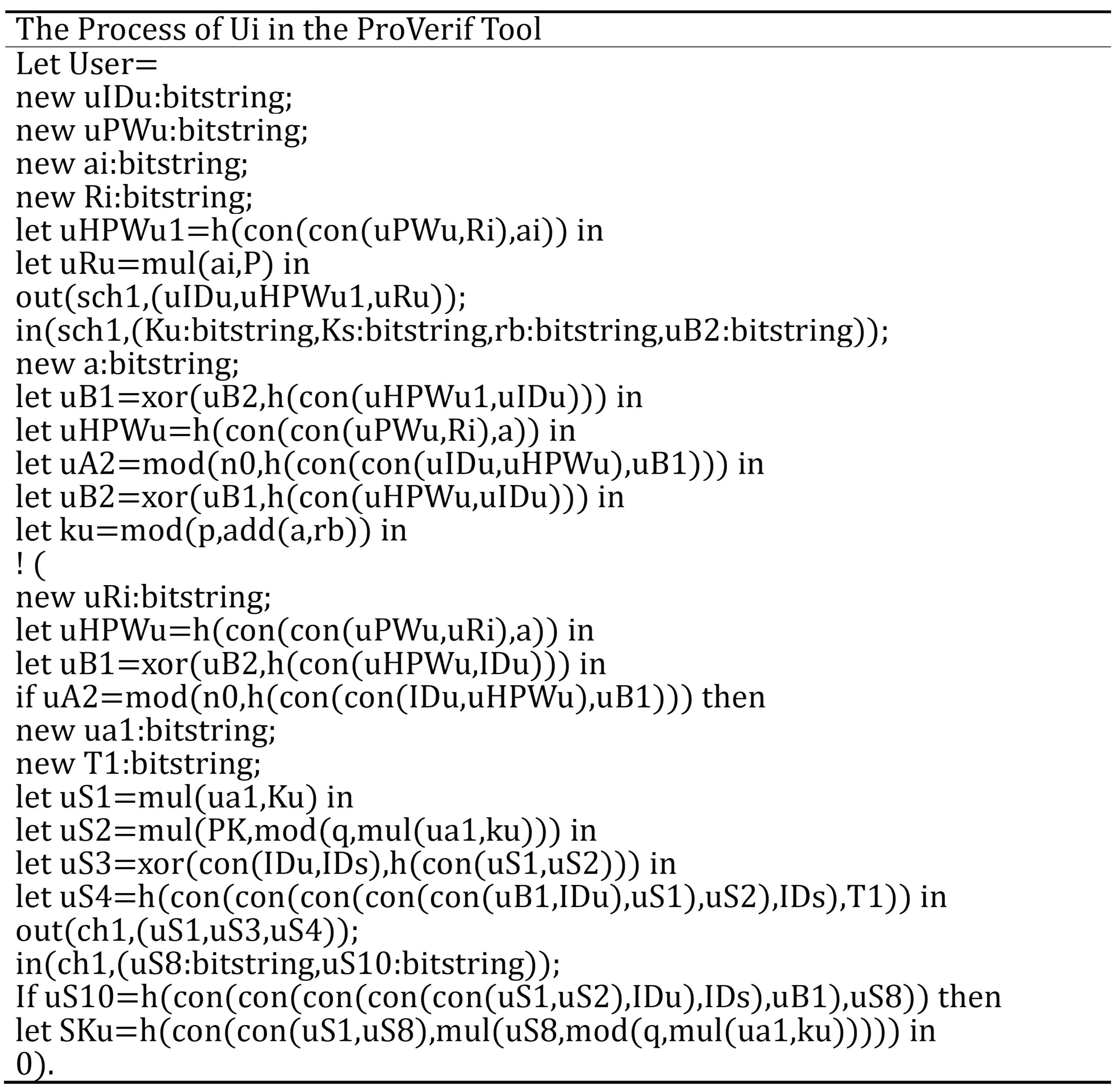

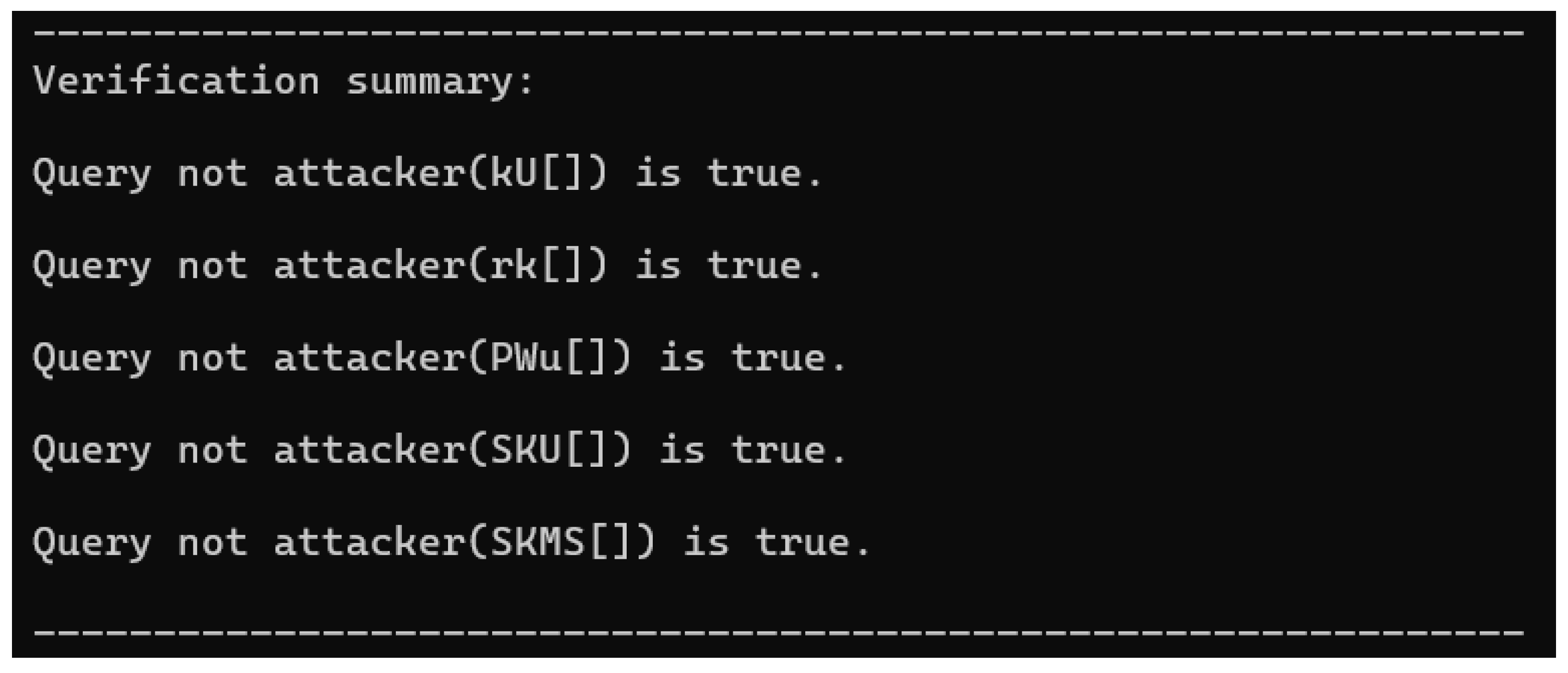

6.3. Automatic Formal Verification by ProVerif

- query attacker(kU).

- query attacker(rk).

- query attacker(PWu).

- query attacker(SKU).

- query attacker(SKMS).

7. Performance Comparison

7.1. Performance Comparison

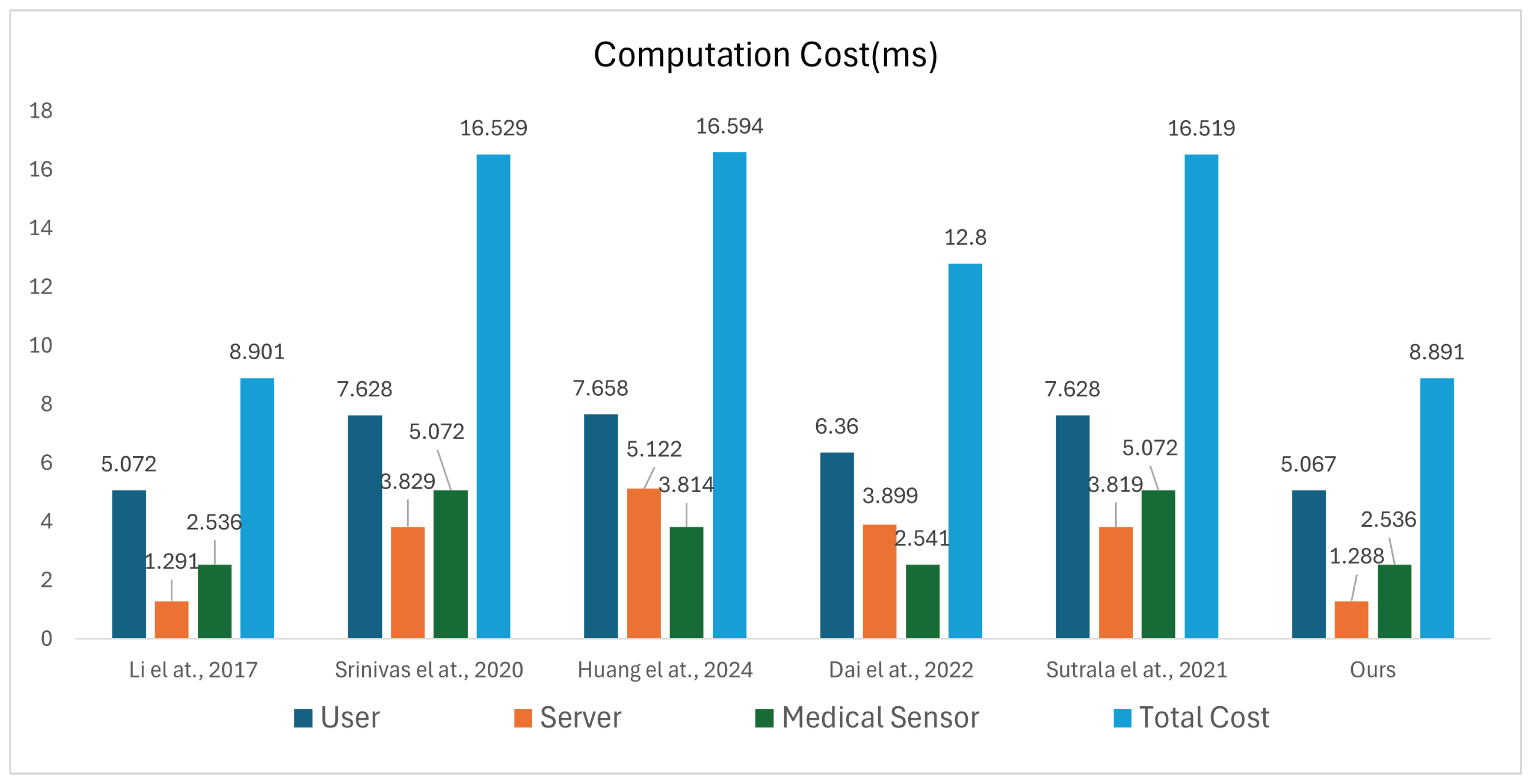

7.2. Computation Cost

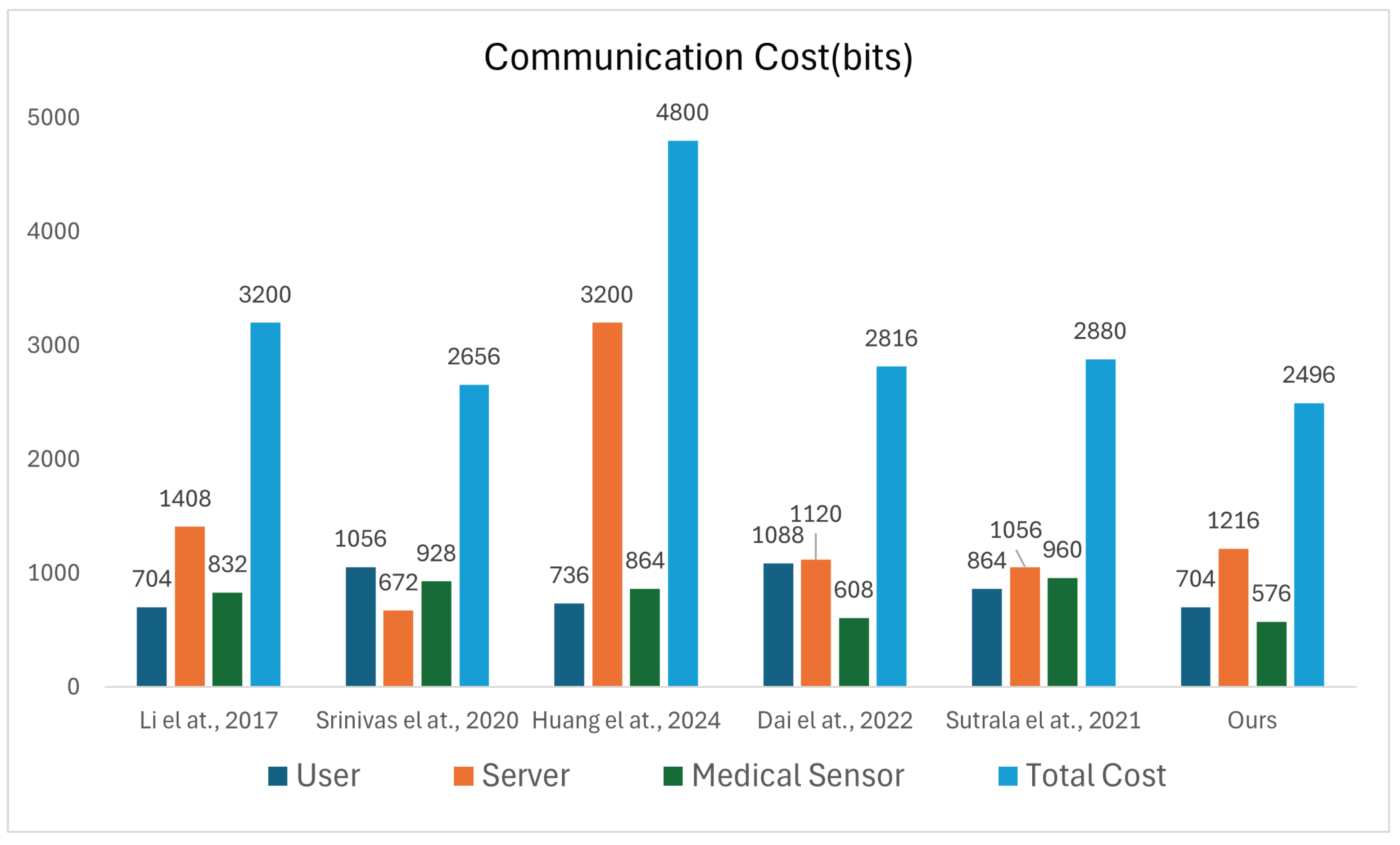

7.3. Communication Cost

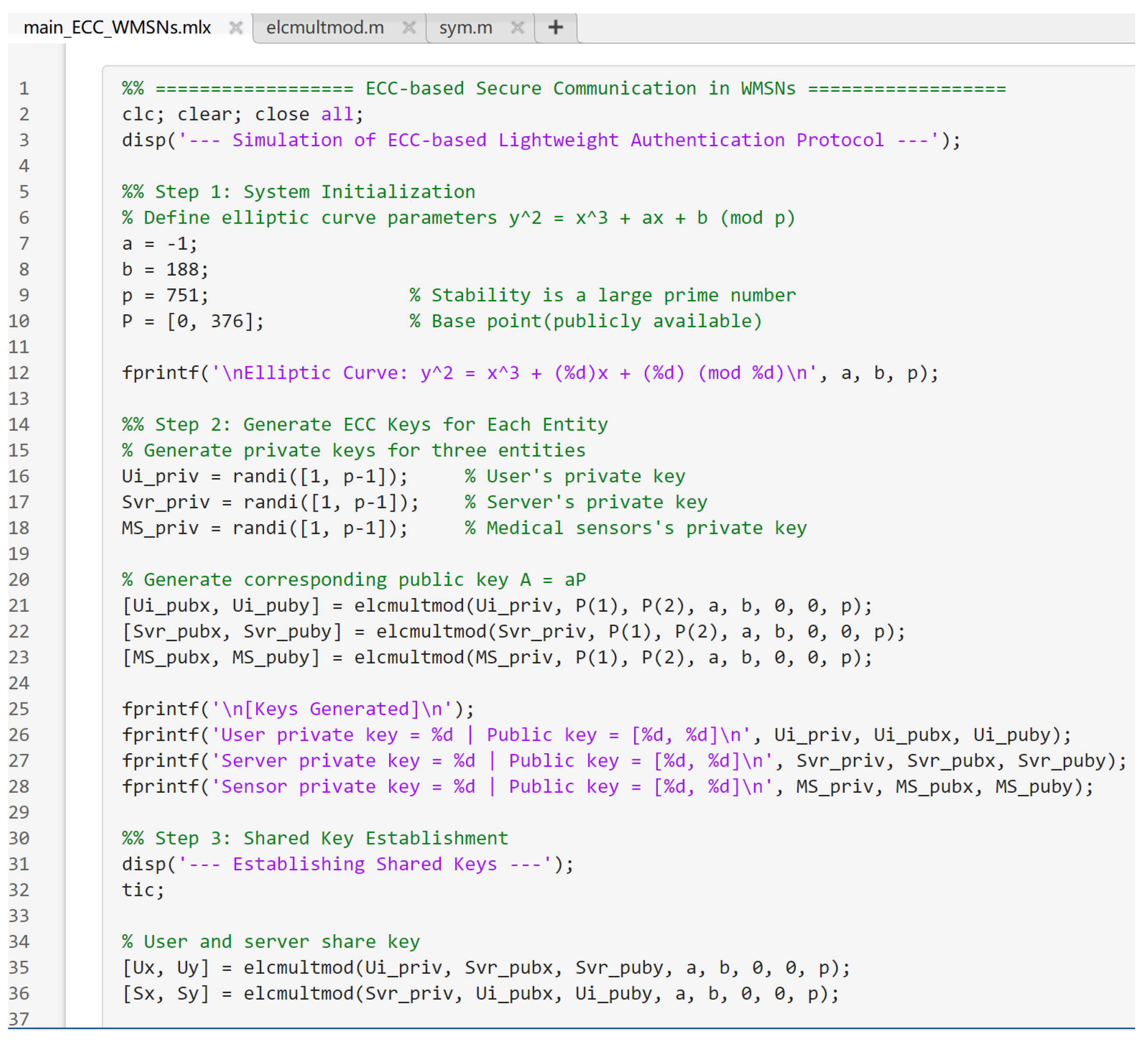

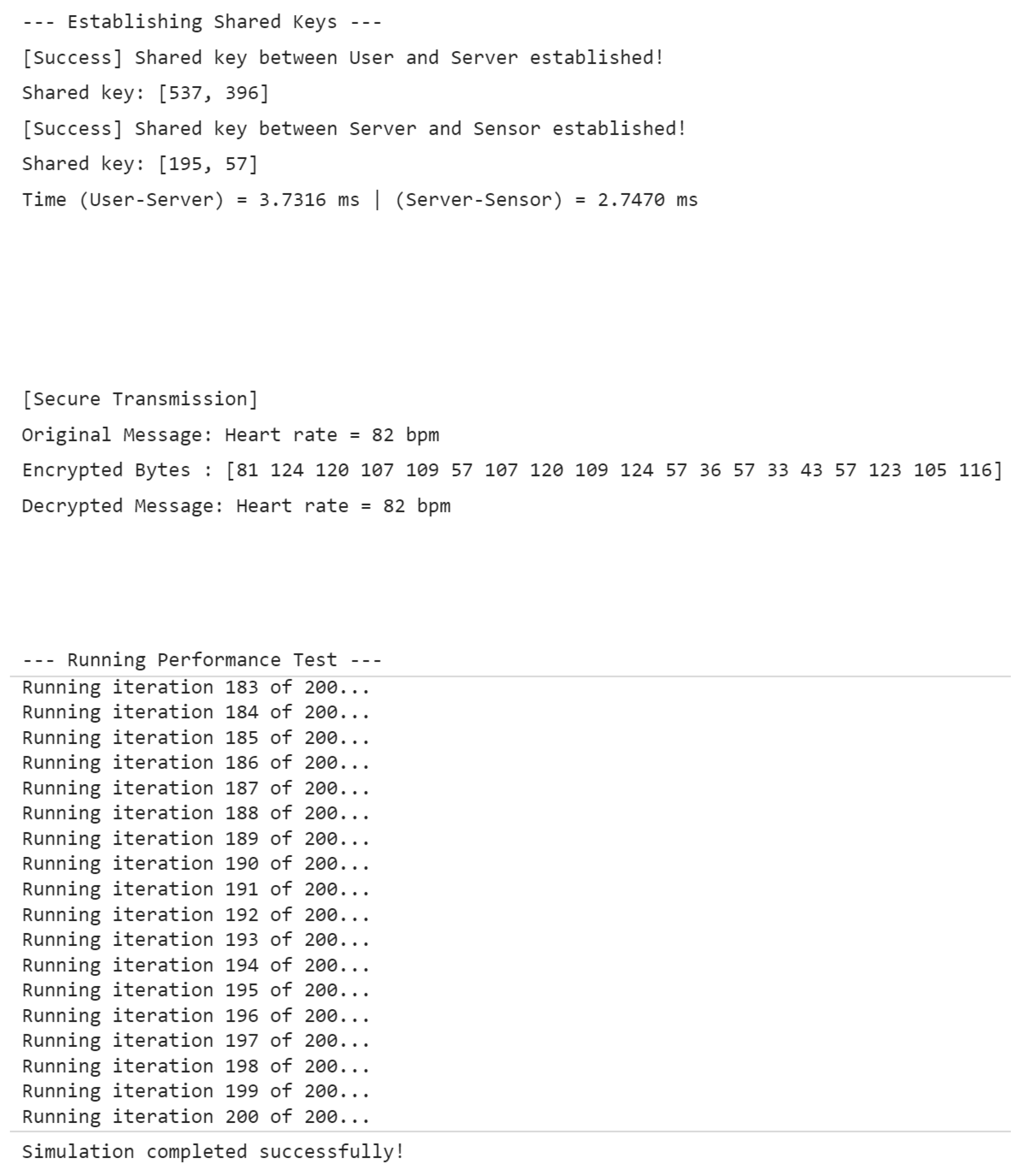

8. Experimental Study

8.1. Simulation of Secure Communication in a Simplified WMSN Model

8.2. Embedded Implementation and Communication Verification

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thakur, G.; Prajapat, S.; Kumar, P.; Das, A.K.; Shetty, S. An efficient lightweight provably secure authentication protocol for patient monitoring using wireless medical sensor networks. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 114662–114679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alladi, T.; Chamola, V.; Naren. HARCI: A two-way authentication protocol for three entity healthcare IoT networks. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2020, 39, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, B.A.; Irshad, A.; Albeshri, A.; Alsubhi, K. A provably secure and lightweight patient-healthcare authentication protocol in wireless body area networks. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2021, 117, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenyeres, M.; Kenyeres, J.; Hassankhani Dolatabadi, S. Distributed consensus gossip-based data fusion for suppressing incorrect sensor readings in wireless sensor networks. J. Low Power Electron. Appl. 2025, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Wazirali, R.; Abu-Ain, T. Machine learning for wireless sensor networks security: An overview of challenges and issues. Sensors 2022, 22, 4730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewangan, K.; Mishra, M.; Dewangan, N.K. A review: A new authentication protocol for real-time healthcare monitoring system. Ir. J. Med. Sci. (1971-) 2021, 190, 927–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamdouh, M.; Awad, A.I.; Khalaf, A.A.; Hamed, H.F. Authentication and identity management of IoHT devices: Achievements, challenges, and future directions. Comput. Secur. 2021, 111, 102491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Jin, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chang, D.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H. A survey: When moving target defense meets game theory. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2023, 48, 100544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Cheng, X.; Wu, H.; Luo, X.; Ma, B.; Zong, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J. A GAN-based anti-forensics method by modifying the quantization table in JPEG header file. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2025, 110, 104462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Xie, Z.; Chen, T.; Cheng, X.; Wen, H. Image privacy protection scheme based on high-quality reconstruction DCT compression and nonlinear dynamics. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 257, 124891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Oh, J.; Park, Y. A secure and anonymous authentication protocol based on three-factor wireless medical sensor networks. Electronics 2023, 12, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, B. An improved authentication protocol for smart healthcare system using wireless medical sensor network. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 105101–105117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Ryu, J.; Lee, Y.; Won, D. An improved lightweight user authentication scheme for the internet of medical things. Sensors 2023, 23, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.; Pal, A.K.; Kumari, S.; Sangaiah, A.K.; Li, X.; Wu, F. An enhanced three factor based authentication protocol using wireless medical sensor networks for healthcare monitoring. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2024, 15, 1165–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Guo, H.; Wu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Liu, J. A novel two-factor multi-gateway authentication protocol for WSNs. Ad Hoc Netw. 2023, 141, 103089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, C.M.; Dwivedi, S.K.; Brindha, M.; Al-Shehari, T.; Alfakih, T.; Alsalman, H.; Amin, R. REPACA: Robust ECC based privacy-controlled mutual authentication and session key sharing protocol in coalmines application with provable security. Peer-to-Peer Netw. Appl. 2024, 17, 4264–4285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazid, M.; Das, A.K.; Kumar, N.; Alazab, M. Designing authenticated key management scheme in 6G-enabled network in a box deployed for industrial applications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 17, 7174–7184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, D.; Duan, Y.; Tao, X. Secure and lightweight user authentication scheme for cloud-assisted Internet of Things. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2023, 18, 2961–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sureshkumar, V.; Amin, R.; Vijaykumar, V.; Sekar, S.R. Robust secure communication protocol for smart healthcare system with FPGA implementation. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 100, 938–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Teng, Y.; Chi, Y.; Hu, H. A robust and anonymous three-factor authentication scheme based ecc for smart home environments. Symmetry 2022, 14, 2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, P. Two Birds with One Stone: Two-Factor Authentication with Security Beyond Conventional Bound. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2018, 15, 708–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, M.; Fouque, P.A.; Pointcheval, D. Password-based authenticated key exchange in the three-party setting. In Proceedings of the Public Key Cryptography-PKC 2005: 8th International Workshop on Theory and Practice in Public Key Cryptography, Les Diablerets, Switzerland, 23–26 January 2005; Proceedings 8. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Q.; Khan, M.K.; Lu, X.; Ma, J.; He, D. A privacy preserving three-factor authentication protocol for e-health clouds. J. Supercomput. 2016, 72, 3826–3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minahil; Ayub, M.F.; Mahmood, K.; Kumari, S.; Sangaiah, A.K. Lightweight authentication protocol for e-health clouds in IoT-based applications through 5G technology. Digit. Commun. Netw. 2021, 7, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta-Ochoa, A.M.; Chaca-Asmal, P.A.; Guerrero-Vásquez, L.F.; Ordoñez-Ordoñez, J.O.; Coronel-González, E.J. Smart healthcare applications over 5G networks: A systematic review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H.; Chung, Y.F. Secure user authentication scheme for wireless healthcare sensor networks. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2017, 59, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challa, S.; Das, A.K.; Odelu, V.; Kumar, N.; Kumari, S.; Khan, M.K.; Vasilakos, A.V. An efficient ECC-based provably secure three-factor user authentication and key agreement protocol for wireless healthcare sensor networks. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2018, 69, 534–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narwal, B.; Mohapatra, A.K. A survey on security and authentication in wireless body area networks. J. Syst. Archit. 2021, 113, 101883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, D. Understanding failures in security proofs of multi-factor authentication for mobile devices. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2022, 18, 597–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, P.K.; Kalra, S. Multi-factor user authentication scheme for IoT-based healthcare services. J. Reliab. Intell. Environ. 2018, 4, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azrour, M.; Mabrouki, J.; Guezzaz, A.; Farhaoui, Y. New enhanced authentication protocol for internet of things. Big Data Min. Anal. 2021, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.K.; Ghaffari, A.; Besharat, S.; Afshari, H. Security of internet of things based on cryptographic algorithms: A survey. Wirel. Netw. 2021, 27, 1515–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; He, D.; Zeadally, S.; Wang, H. Anonymous biometrics-based authentication scheme with key distribution for mobile multi-server environment. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2018, 84, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ibrahim, M.H.; Kumari, S.; Sangaiah, A.K.; Gupta, V.; Choo, K.K.R. Anonymous mutual authentication and key agreement scheme for wearable sensors in wireless body area networks. Comput. Netw. 2017, 129, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koya, A.M.; Deepthi, P. Anonymous hybrid mutual authentication and key agreement scheme for wireless body area network. Comput. Netw. 2018, 140, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H.; Kim, H. Privacy-preserving authentication protocol for wireless body area networks in healthcare applications. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.; Chatterjee, S.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Gupta, A.K. A biometrics-based robust and secure user authentication protocol for e-healthcare service. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics (ICACCI), Jaipur, India, 21–24 September 2016; pp. 638–644. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Ding, S.; Ho-Ching Iu, H.; Erkan, U.; Toktas, A.; Simsek, C.; Wu, R.; Xu, X.; Cao, Y.; Mou, J. A three-dimensional memristor-based hyperchaotic map for pseudorandom number generation and multi-image encryption. Chaos 2025, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Q.; Ding, S.; Iu, H.H.C.; Cao, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, C.; Mou, J. Encrypt a Story: A Video Segment Encryption Method Based on the Discrete Sinusoidal Memristive Rulkov Neuron. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thousands of Servers Password and Sensitive Information. 2018. Available online: www.solidot.org (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Dolev, D.; Yao, A. On the security of public key protocols. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1983, 29, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Cheng, H.; Wang, P.; Huang, X.; Jian, G. Zipf’s law in passwords. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2017, 12, 2776–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, D.; Tu, Y.; Xu, G.; Wang, H. Understanding node capture attacks in user authentication schemes for wireless sensor networks. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2020, 19, 507–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazid, M.; Das, A.K.; Odelu, V.; Kumar, N.; Conti, M.; Jo, M. Design of secure user authenticated key management protocol for generic IoT networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2017, 5, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, J.; Chen, H. A lightweight secure user authentication and key agreement protocol for wireless sensor networks. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2019, 2019, 2136506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Niu, J.; Bhuiyan, M.Z.A.; Wu, F.; Karuppiah, M.; Kumari, S. A robust ECC-based provable secure authentication protocol with privacy preserving for industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2017, 14, 3599–3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, J.; Das, A.K.; Wazid, M.; Vasilakos, A.V. Designing secure user authentication protocol for big data collection in IoT-based intelligent transportation system. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 8, 7727–7744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W. ECC-based three-factor authentication and key agreement scheme for wireless sensor networks. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Xu, Z. A secure three-factor authentication scheme for multi-gateway wireless sensor networks based on elliptic curve cryptography. Ad Hoc Netw. 2022, 127, 102768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutrala, A.K.; Obaidat, M.S.; Saha, S.; Das, A.K.; Alazab, M.; Park, Y. Authenticated key agreement scheme with user anonymity and untraceability for 5G-enabled softwarized industrial cyber-physical systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 23, 2316–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, K. Micro-ECC Source Code. 2023. Available online: https://github.com/kmackay/micro-ecc (accessed on 10 September 2025).

| Notation | Description | Notation | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| ith user | jth medical sensor | ||

| kth server | an attacker | ||

| user’s smart device | user’s biometric | ||

| identity of | password of | ||

| identity of | T | timestamp | |

| private key of | public key of | ||

| private key of | public key of | ||

| private key | public key | ||

| session key | fuzzy extractor | ||

| → | public channel | ⇢ | security channel |

| No. | Security Requirements | Definition in WMSNs |

|---|---|---|

| C1 | No Password Verifier Table | doesn’t need to store the ’s password or the derived values of the ’s password. |

| C2 | Password Friendly | is allowed to select their password and change it directly on . |

| C3 | Session Key Agreement | Following the authentication process, a shared session key is generated between and to enable secure communication. |

| C4 | Mutual Authentication | and , as well as and , can mutually authenticate each other’s authenticity. |

| C5 | Sound Repairability | The scheme enables to revoke their without altering their identities. Moreover, it allows for the dynamic integration of sensor nodes. |

| C6 | User Anonymity | The scheme protects the ’s true identity, preventing the tracking of activities. |

| C7 | Resistance to Known Attacks | The scheme is capable of defending against various known attacks, including user impersonation attacks, de-synchronization attacks, replay attacks, offline dictionary guessing attacks, and others. |

| C8 | Resistance to Smart Device Loss Attacks | Even if captures the smart device/card and extracts the parameters, they cannot recover the password nor use a password guessing attack to impersonate the user. |

| C9 | Forward Secrecy | Leaking long-term keys will not impact the security of previous sessions. |

| C10 | Resistance to Node Capture Attacks | cannot compromise the protocol by capturing the medical sensor. |

| C11 | Resistance Insider Attack | The legitimate user’s password information and session key cannot be directly accessed by the server, nor can it be obtained through simple computations. |

| C12 | Resistance ESL Attack | In the scheme, even if the random numbers are leaked, the security of the protocol will not be compromised. |

| Scheme | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | C7 | C8 | C9 | C10 | C11 | C12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [46] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | ✓ | × | × | × |

| [47] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × | ✓ | × | ✓ | × |

| [48] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × |

| [49] | ✓ | × | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | × | ✓ | ✓ | × |

| [50] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × | ✓ | ✓ | × |

| Ours | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Scheme | User (ms) | Server (ms) | Medical Sensor (ms) | Total Cost (ms) | Total () |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [46] | |||||

| [47] | |||||

| [48] | |||||

| [49] | |||||

| [50] | |||||

| Ours | - |

| Scheme | Server (ms) | Total () |

|---|---|---|

| [46] | ||

| [47] | ||

| [48] | ||

| [49] | ||

| [50] | ||

| Ours | - |

| Scheme | N. | User (Bit) | Server (Bit) | Medical Sensor (Bit) | Total Cost (Bit) | Total () |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [46] | 4 | 3200 | ||||

| [47] | 3 | 2656 | ||||

| [48] | 4 | 4800 | ||||

| [49] | 4 | 2816 | ||||

| [50] | 4 | 2880 | ||||

| Ours | 4 | 2496 | - |

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| Operating system | Windows 10/11 |

| Cryptographic library | Micro-ECC |

| communication module | ESP-12F |

| Elliptic curves | Secp160r1, Secp192r1, Secp256k1 |

| Hash function | SHA-256 |

| Programming language | C (C Free 5)/Python 3.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shang, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, K. A Secure and Lightweight ECC-Based Authentication Protocol for Wireless Medical Sensors Networks. Sensors 2025, 25, 6567. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216567

Shang Y, Chen J, Wang S, Zhang Y, Ma K. A Secure and Lightweight ECC-Based Authentication Protocol for Wireless Medical Sensors Networks. Sensors. 2025; 25(21):6567. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216567

Chicago/Turabian StyleShang, Yu, Junhua Chen, Shenjin Wang, Ya Zhang, and Kaixuan Ma. 2025. "A Secure and Lightweight ECC-Based Authentication Protocol for Wireless Medical Sensors Networks" Sensors 25, no. 21: 6567. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216567

APA StyleShang, Y., Chen, J., Wang, S., Zhang, Y., & Ma, K. (2025). A Secure and Lightweight ECC-Based Authentication Protocol for Wireless Medical Sensors Networks. Sensors, 25(21), 6567. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216567