3.1. The Performance of the Sensor by Optimizing Device Structure Performance

In our experiments, we primarily focused on the gas-sensing performance parameters of response, response time, and recovery time. We focused more on analyzing the gas-sensing characteristics of sensors for NO

2 using response values rather than the response itself. Among these parameters, the response is defined as R

t/R

0 [

11], where R

0 is the value of resistance in N

2 and R

t is the value of test resistance. The gas-sensitive detection device has a preset time of 120 s to inflate the background gas, and the response time (t

resp) is the time it takes for the sensor to reach 90% of the steady-state resistance value after contact with the target gas. Similarly, recovery time (t

rec) refers to the time it takes for the resistance to return to 90% R

0 after NO

2 is removed from the test chamber. Additionally, the responsivity–concentration gradient and response recovery time of the sensor to NO

2 can be evaluated by setting the pulse ventilation mode in the test system. First, the background gas is continuously passed in until the resistance is stable. Then the test gas and background gas are alternately passed in for 300 s, and the concentrations of the test gas are 50, 100, 150, 200, and 250 ppm. The response and recovery time of the gas sensor to NO

2 are tested in response and recovery modes. Similarly, the background gas needs to be passed in until the resistance is stable. Then, the test gas, with a concentration of 250 ppm, is passed in, followed by the background gas for 120 and 300 s, respectively.

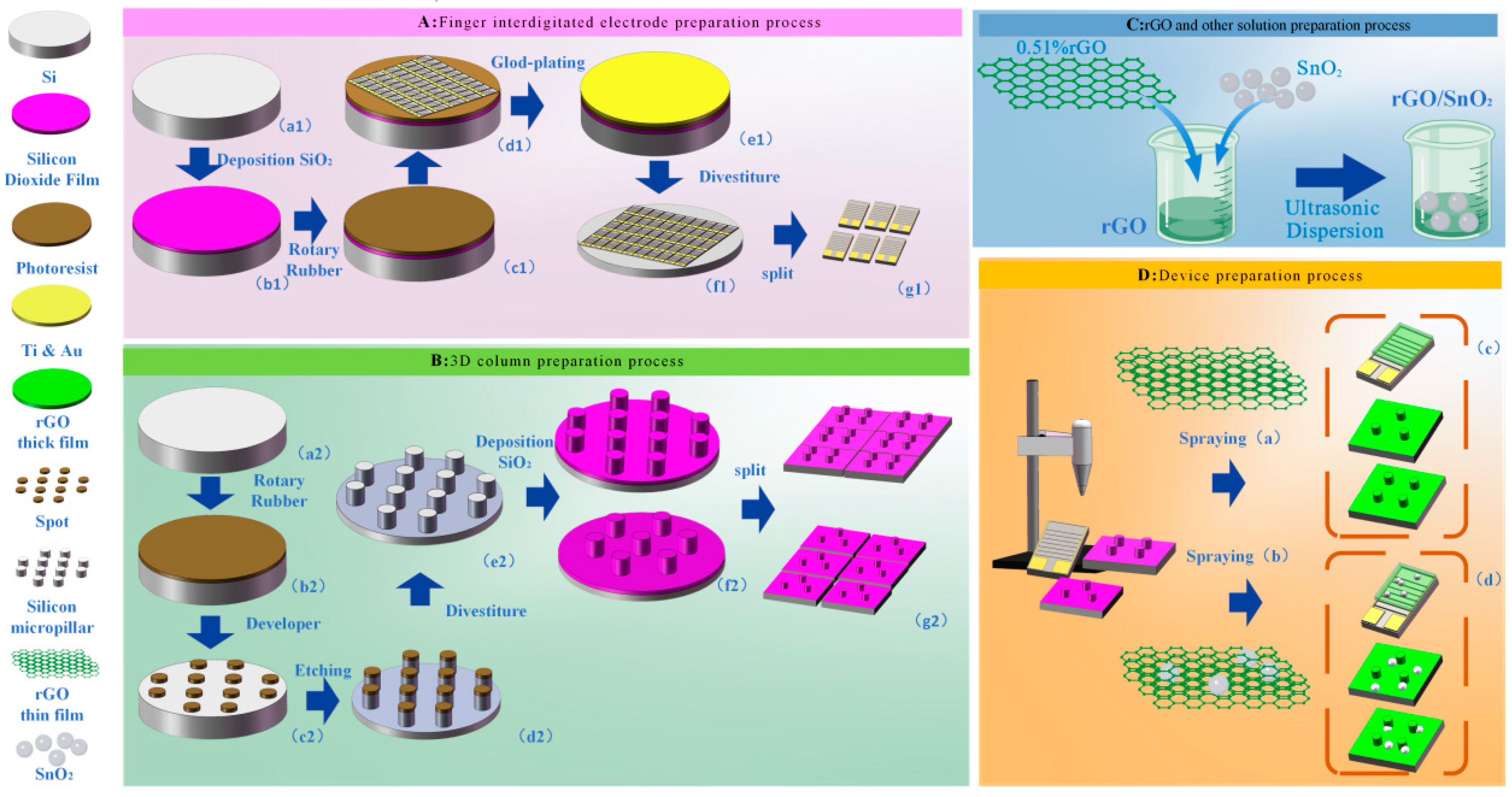

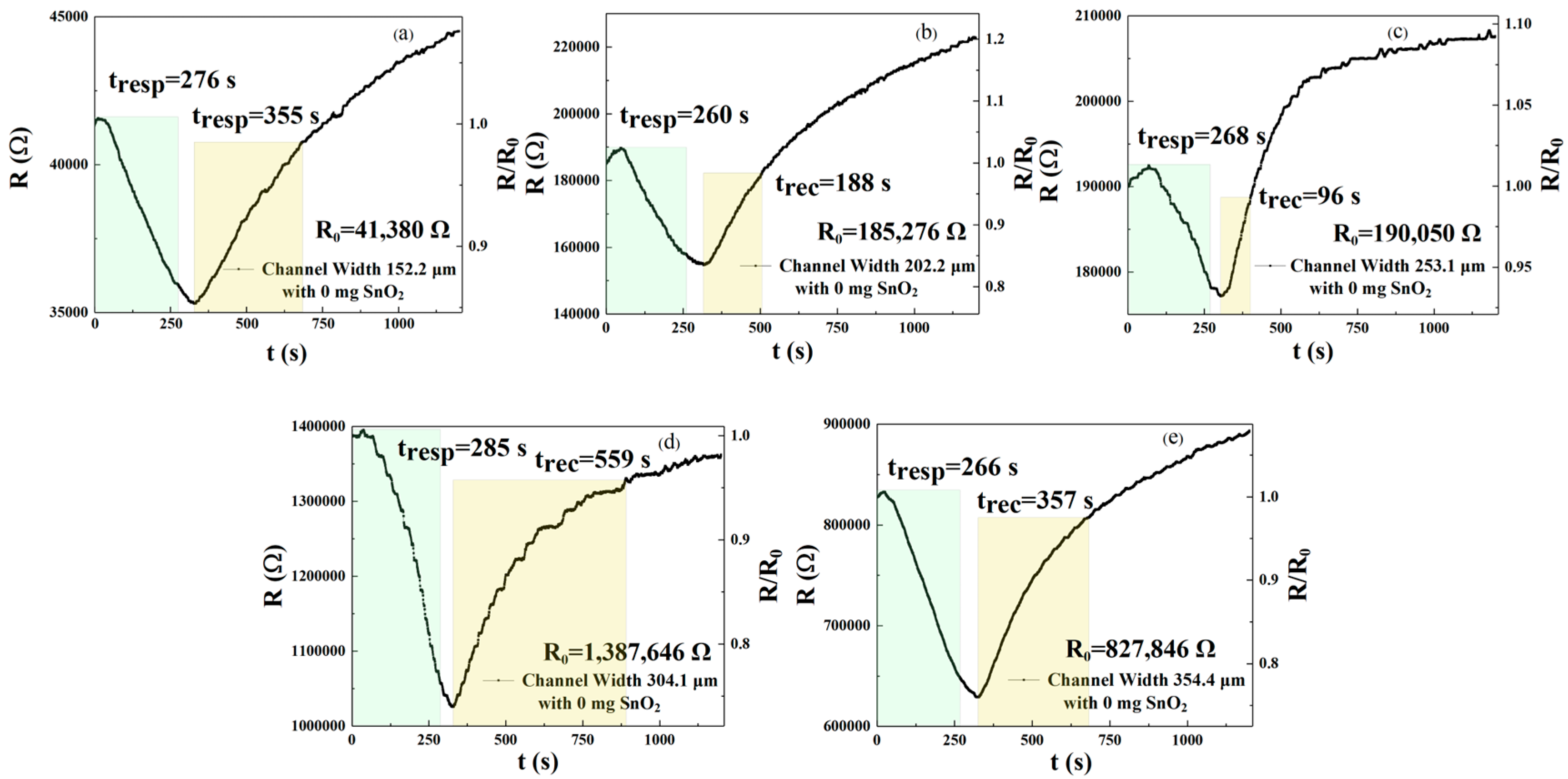

In this experiment, we selected interdigital electrodes with widths of 152.2, 202.2, 253.1, 304.1, and 354.4 μm. We sprayed these with the same amount of rGO (see

Figure 1C, rGO) to study the effects of interdigital electrodes of different widths on the performance of the gas sensor.

Figure 2a–e show the response time and recovery time of a gas sensor detecting 250 ppm NO

2 on five interdigital electrodes of different widths at a test temperature of 30 °C. We defined the response time and recovery time using a channel width of 304.1 μm as the reference value. The improvement rate of response time can be defined as

(where w represents the sample corresponding to w

1 = 152.2 μm, w

2 = 202.2 μm, w

3 = 253.1 μm, w

4 = 304.1 μm, and w

5 = 354.4 μm):

When

is negative, it means that the response speed of this width is improved relative to the interdigital electrodes of width 304 μm, and the larger the value, the shorter the response time. Similarly, the improvement rate of the recovery time can be defined as

Based on the response and recovery times of sensors of different widths (w

1 = 152.2 μm, w

2 = 202.2 μm, w

3 = 253.1 μm, w

4 = 304.1 μm, and w

5 = 354.4 μm) (

Table 1), we calculated the values for the two improvement rates for each device. The response times of the sensors (of five widths) are 276, 260, 268, 285, and 266 s, and the recovery times are 355, 188, 96, 559, and 357 s, respectively. Sensors of width w

1, w

2, w

3, and w

5 reduced the response times by 3.1%, 8.8%, 6%, and 6.7%, respectively, compared with gas-sensitive sensors of width w

4, while recovery times for widths w

1, w

2, w

3, and w

5 decreased by 36.5%, 66.4%, 82.8%, and 36.1%, respectively. Based on these results, the most significant improvement in response speed was observed in sensors with a channel width of w

2 = 202.2 μm, resulting in an 8.8% reduction in response time. In contrast, the best recovery speed was achieved by sensors with a channel width of w

3 = 253.1 μm, resulting in an 82.8% reduction in recovery time.

The sensors’ responsivity to NO

2 can be calculated from the data on the right axis in

Figure 2a–e. The responsivity values of the gas sensors (of five widths) are 1.172, 1.197, 1.073, 1.352, and 1.316, respectively. As can be seen from the above data, when comparing w

1, w

2, w

3, and w

5, the responsivity values are the highest under the w

4 condition. We define the responsivity ∆R, the slope of the response–concentration linear fit line [

15], as

where R

Y is the analysis value, and R

X is the reference value. When ∆R is positive, it means that the responsivity of the gas sensor is increased under Y conditions relative to X, and the larger the value, the greater the increase. When ∆R is negative, it means that the responsivity of the gas sensor under condition Y is lower than that under condition X. The higher the absolute value of ∆R, the greater the decline. We selected X = w

3 to analyze the device responsivity values for all Y values. At 250 ppm NO

2 concentration, the ∆R of w

1, w

2, w

4, and w

5 is 9.22%, 11.56%, 25.72%, and 22.65%, respectively. Based on the above analysis, the improvement rate of the w

2 response recovery is higher than that of other sensors’ rates, indicating that the response time is shorter, although the responsivities of w

4 and w

5 are higher. Therefore, gas sensors with a channel width of w

2 have better gas detection characteristics. Next, we present a further exploration of the effects of doping with varying amounts of SnO

2 on the gas detection performance of these devices.

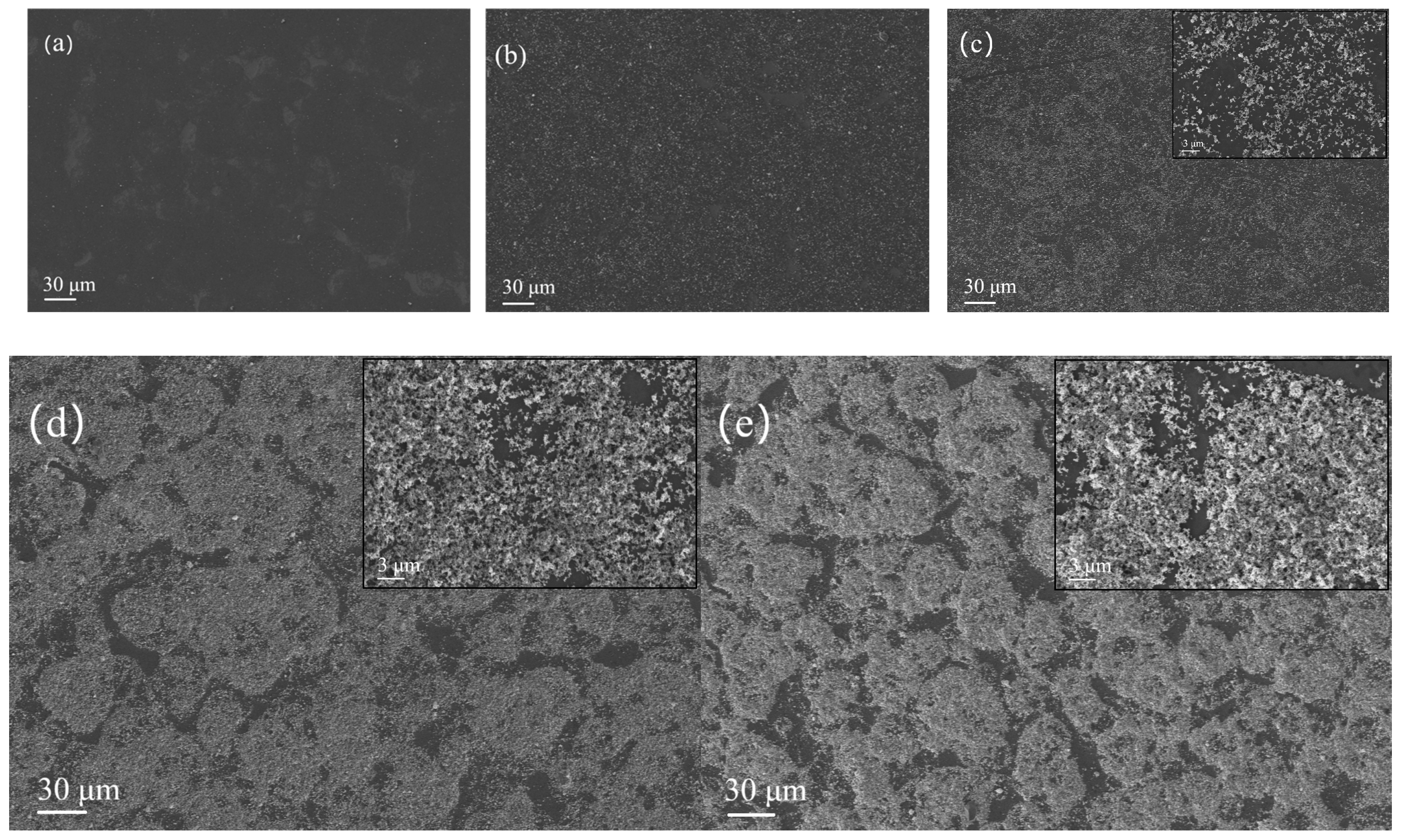

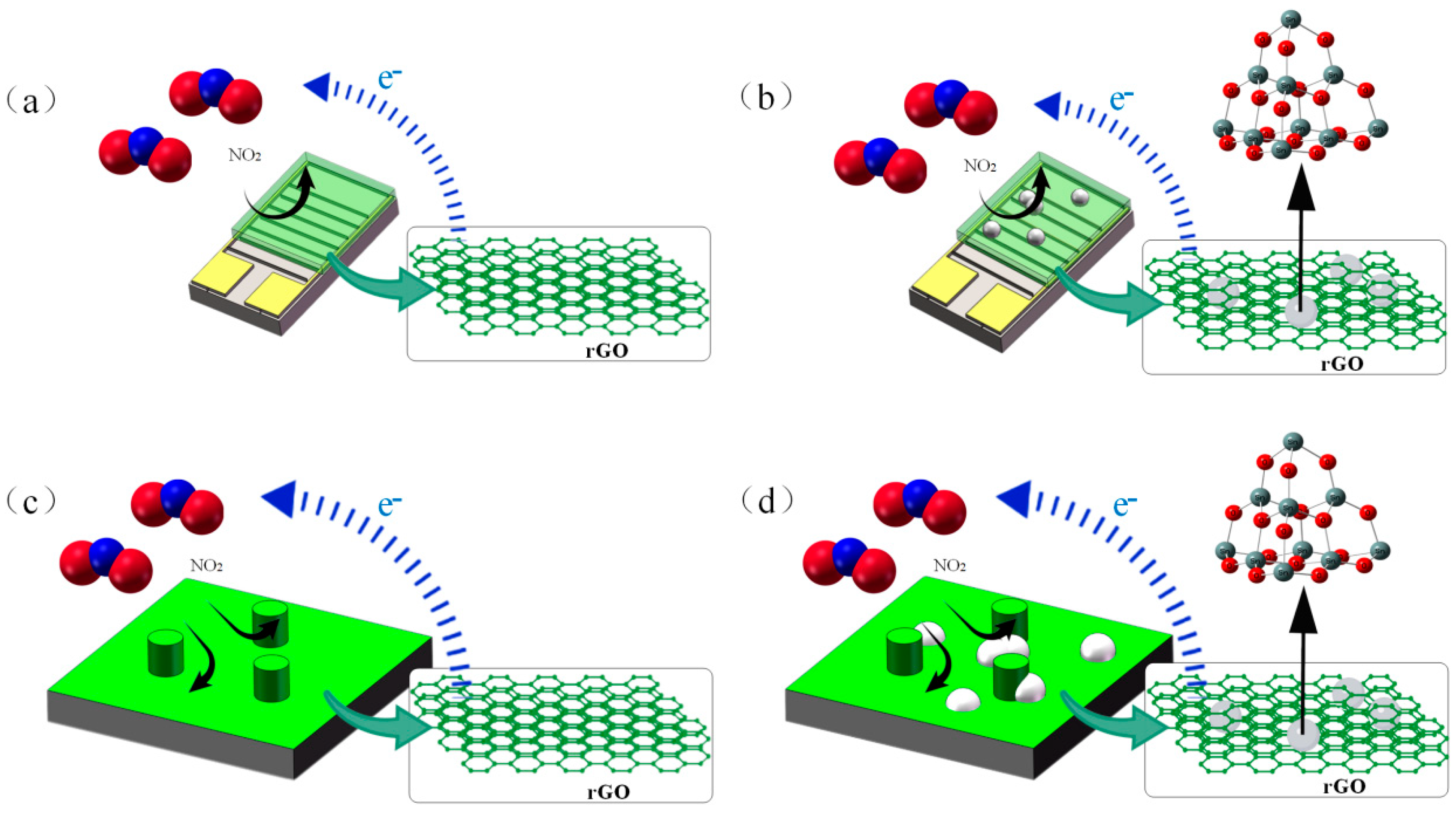

The image series shown in

Figure 3 displays scanning electron microscopy of rGO/SnO

2 composite gas-sensitive materials with silicon-based interdigital electrodes (width: 202.2 μm).

Figure 3a–e correspond to samples with SnO

2 doping amounts of 0, 10, 20, 100, and 160 mg, respectively. After drying at 80 °C for 2 h, the bright white area in the microstructure consists of SnO

2 particles, and the deep black substrate is an rGO film. The upper right corners of

Figure 3c–e provide a magnified view of the key area, which clearly shows how rGO/SnO

2 particles are distributed on the surface of the gas sensor. Despite there being some incomplete coverage areas, small-scale pores do not significantly affect the charge transport performance of the gas-sensitive film, enabling effective contact between the material and the electrode; the composite layer above the sensor channel forms a stable electrical connection with the electrode, ensuring efficient carrier migration when the target gas is exposed. Additionally, the oxygen-containing functional groups on the surface of rGO may anchor SnO

2 nanoparticles through chemical bonding, significantly enhancing the sensor’s responsivity to NO

2.

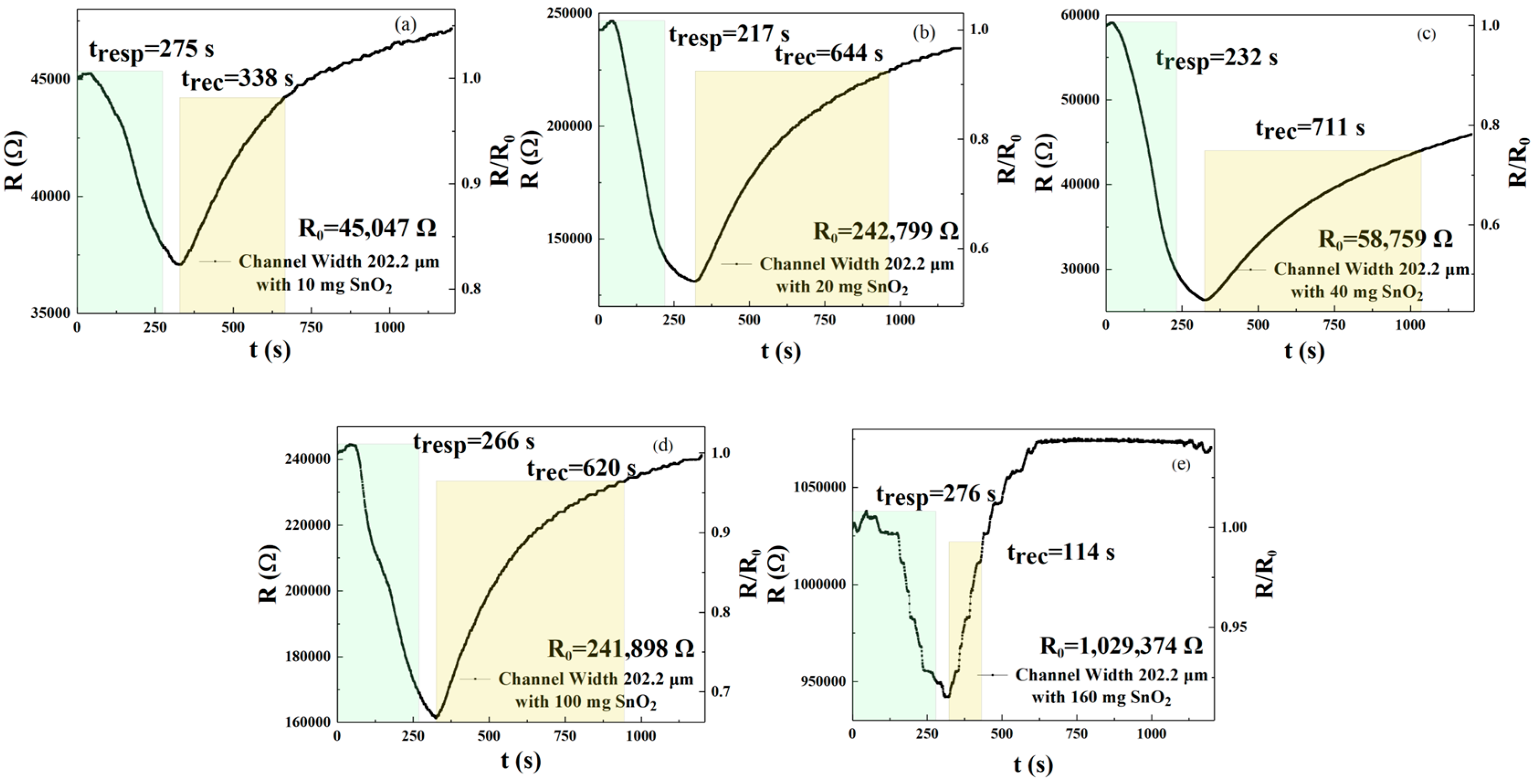

In this experiment, we prepared an rGO solution doped with five different amounts of SnO

2 and sprayed it onto an interdigital electrode surface with the channel width that had the best performance in the previous experiment. We then used this setup as a sensor in the presence of NO

2 at a concentration of 250 ppm. As shown in

Figure 4a–e, the response recovery time and responsivity of the five sensor devices were tested for gas responsivity, respectively.

Figure 4a–e and

Table 2 describe the response and recovery curves and times for the 250 ppm NO

2 condition for five different concentrations (in milligrams) of SnO

2 in rGO solution. For these sensors, the response times for the five different concentrations (in milligrams) were 275, 217, 232, 266, and 276 s, respectively. The recovery times were 338, 644, 711, 620, and 114 s, respectively. According to Formulas (1) and (2), sensors doped with 10 mg (m

1), 20 mg (m

2), 40 mg (m

3), and 100 mg (m

4) reduced response times by 0.36%, 21.4%, 15.9%, and 3.6%, respectively, when compared with gas-sensitive sensors doped with 160 mg (m

5). Sensors doped with 10 mg (m

1), 20 mg (m

2), 40 mg (m

3), and 100 mg (m

4) had a reduction in recovery time of −196.5%, −464.9%, −523.7%, and −443.9%, respectively. Therefore, the sensor doped with 20 mg shows the best response and recovery speed.

The response curves for NO

2 and sensors doped with different amounts of SnO

2 can also be calculated using

Figure 4a–e. When doped with 10, 20, 40, 100, and 160 milligrams, the response values were 1.215, 1.849, 2.228, 1.499, and 1.092, respectively. Based on the above data, the sensor doped with 40 mg (m

3) exhibits the best response when compared with the m

1, m

2, m

4, and m

5 gas-sensitive sensors, respectively. According to Formula (3), the responsivity of the m

2 = 20 mg sensor increased by 52.1%, −260%, 23.3%, and 69.32%, when compared to the m

1, m

3, m

4, and m

5 gas-sensitive sensors, respectively. The above results show that the rGO solution doped with 20 mg of SnO

2 has a high response value compared to the other doping amounts. Therefore, for this specific solution concentration, it is possible to adjust the width of the interdigital electrode to improve the coverage rate of the rGO film on the non-insulating layer (on the surface of the substrate), thereby more effectively adjusting the gas responsivity of the sensor device. We will discuss this in detail below.

As shown in

Figure 5a–e, in this experiment, we selected the m

2 doping concentration as the parameter for preparing the next sensor samples.

Figure 5a–e and

Table 3 describe the response and recovery curves and times of sensors with different interdigital electrode widths sprayed with an rGO solution doped with 20 mg of SnO

2. The results show response times of 188, 217, 251, 235, and 195 s and recovery times of 842, 644, 656, 643, and 684 s for the five sensors, respectively. According to Formulas (1) and (2), sensors with w

1, w

2, w

3, and w

5 channel widths reduced response times by 25.10%, 13.55%, 6.37%, and 22.31%, respectively, compared with the sensor of channel width w

3 = 253.1 μm. Sensors with w

1, w

2, w

3, and w

5 channel widths exhibit reductions in recovery time of −28.35%, 1.83%, 1.98%, and −4.27%, respectively. Therefore, sensors with a channel width of w

1 = 152.2 μm exhibit the best response and recovery speed. When the channel width is w

1 = 152.2 μm, w

2 = 202.2 μm, w

3 = 253.1 μm, w

4 = 304.1 μm, and w

5 = 354.4 μm, the responses were 1.388, 1.849, 1.621, 1.345, and 1.899, respectively, at the concentration of 250 ppm NO

2. The results demonstrate that the sensor with a channel width of w

5 = 354.4 μm exhibited the best response compared with channel widths of w

1, w

2, w

3, and w

4. According to Formula (3), a channel width of w

5 = 354.4 μm improves responsivity by 36.82%, 2.70%, 17.15%, and 41.19%, respectively, when compared with sensors of channel width w

1, w

2, w

3, and w

4. The above results indicate that a small amount of SnO

2 in rGO can improve performance. The reason why rGO/SnO

2 can improve a sensor’s performance may be that the oxygen-containing functional groups on the rGO surface assist in the adsorption of SnO

2 through chemical bonding, thereby enhancing the sensor’s responsivity to NO

2. Second, when the added content exceeds a certain value (20 mg in this experiment), a large amount of SnO

2 will accumulate, which can easily block the original pores of rGO and hinder the interaction between NO

2 gas and rGO. Therefore, the 20 mg rGO/SnO

2 condition has the best sensing performance. Gas-sensitive sensors prepared using interdigital electrodes of specific widths exhibit excellent gas responsivity characteristics at a certain concentration of NO

2. After our analysis, the reasons may be as follows. First, when the width-to-gap ratio of the electrode changes, the influence of interface and film resistance on responsivity can be relatively reduced, thereby improving responsivity performance. Second, if the channel width is too large, it will also lead to an increase in the Schottky Barrier Height [

16], which can result in higher contact resistance with the gas, causing a longer response recovery time and a decrease in responsivity. Based on the above, it is evident that increasing the rGO active site on the sensor’s surface can enhance its performance. Next, we will further explore whether the sensor’s gas detection performance can be improved by increasing the specific surface area of the sensor through the creation of three-dimensional columns.

The Raman spectrum for pure rGO (

Figure 6a) has two characteristic peaks at 1345 and 1606 cm

−1, corresponding to the D and G peaks, respectively, confirming the presence of rGO material. The peak at 1345 cm

−1 is the D peak, which originates from the breathing vibration mode of sp

2 hybridized carbon atoms in the carbon lattice. Therefore, the presence of the D peak indicates structural disorder, defects, or edges in the material. The peak at 1606 cm

−1 is the G peak, resulting from the in-plane stretching vibrations of sp

2 hybridized carbon bonds. These two peaks are characteristic features common to all graphitized carbon materials, indicating that rGO has been successfully coated onto the interdigital electrodes. The broad peak around 2700 cm

−1 is the 2D peak (or G’ peak), which is a second-order Raman peak arising from two-phonon resonance. Its broadened line shape and lower intensity correlate with the multi-layered and defect-rich characteristics of rGO. The clear observation of the D and G peaks in this spectrum indicates that the prepared material is a typical rGO specimen, containing both sp

2 carbon domains and numerous defects in its structure. From

Figure 6a–f, the values of I

D/I

G are 1.22, 1.19, 1.29, 1.17, 1.24, and 1.28, respectively. This indicates that the reduction process successfully removed most oxygen-containing functional groups, thereby restoring the sp

2 carbon network, and that a large number of ‘defects’ were formed at the boundaries of these small sp

2 domains within the material. The higher defect density provides more active sites, which is beneficial for the adsorption of gas molecules.

3.2. Silicon Micropillar Gas Sensor Performance

A series of scanning electron microscopy image systems (

Figure 7) show the morphological characteristics of the rGO/SnO

2 solution at different concentrations on the surface of the micropillars (including a pure rGO solution and a solution doped with 20 mg SnO

2) with different spatial arrangements: a–b correspond to the square array arrangement, and c–d correspond to the triangle array arrangement. The upper right corner of each image is embedded with a magnified view of the key area, and e–h represent the oblique viewing angle of a–d, respectively. As shown in

Figure 7, the three-dimensional cylinder structure exhibits significant advantages over the flat substrate. The gas-sensitive material forms an extended interface on the three-dimensional surface, greatly increasing the effective contact area with the target gas; this enables the sensor to have a faster response speed and higher detection responsivity to the target gas.

Figure 8a–f shows that the cylindrical gas-sensitive materials exhibit a similar Raman spectrum and peaks to the interdigital electrode gas-sensitive materials, with peaks at approximately 1350, 1600, and 2700 cm

−1. This indicates that they share similar physical properties with the interdigital electrode gas-sensitive materials. From

Figure 8a–f, the values of I

D/I

G are 1.34, 1.23, 1.28, 1.43, 1.32, and 1.21, respectively. These results confirm that the incorporation of SnO

2 nanoparticles effectively disrupts the rGO lattice and increases defect density. Furthermore, the sensors with optimal gas response—the square array with 20 mg SnO

2 and the triangular array with 160 mg SnO

2—exhibit lower I

D/I

G ratios, confirming that an increase in defects contributes to enhanced gas response performance.

The g and h compares the XRD spectra of rGO solutions with 160 mg SnO2 and without SnO2 doping, sprayed onto cylindrical gas-sensitive materials arranged in a triangle pattern. It can be seen that, compared with g the spectrum in h displays three main characteristic peaks, corresponding to crystal orientations: (110), (101), and (211). These three crystal orientations indicate the presence of SnO2 particles. The characteristic peaks can be indexed according to the standard tetragonal rutile structure (JCPDS card, no. 41-1445).

In this experiment, we selected three-dimensional cylinders made of silicon as the experimental material, which have a diameter of 6.0 μm and a distribution period of 14.5 μm. The array has a square arrangement, sprayed with six different concentrations of rGO/SnO

2; the prepared sensors were tested for response recovery time and responsivity.

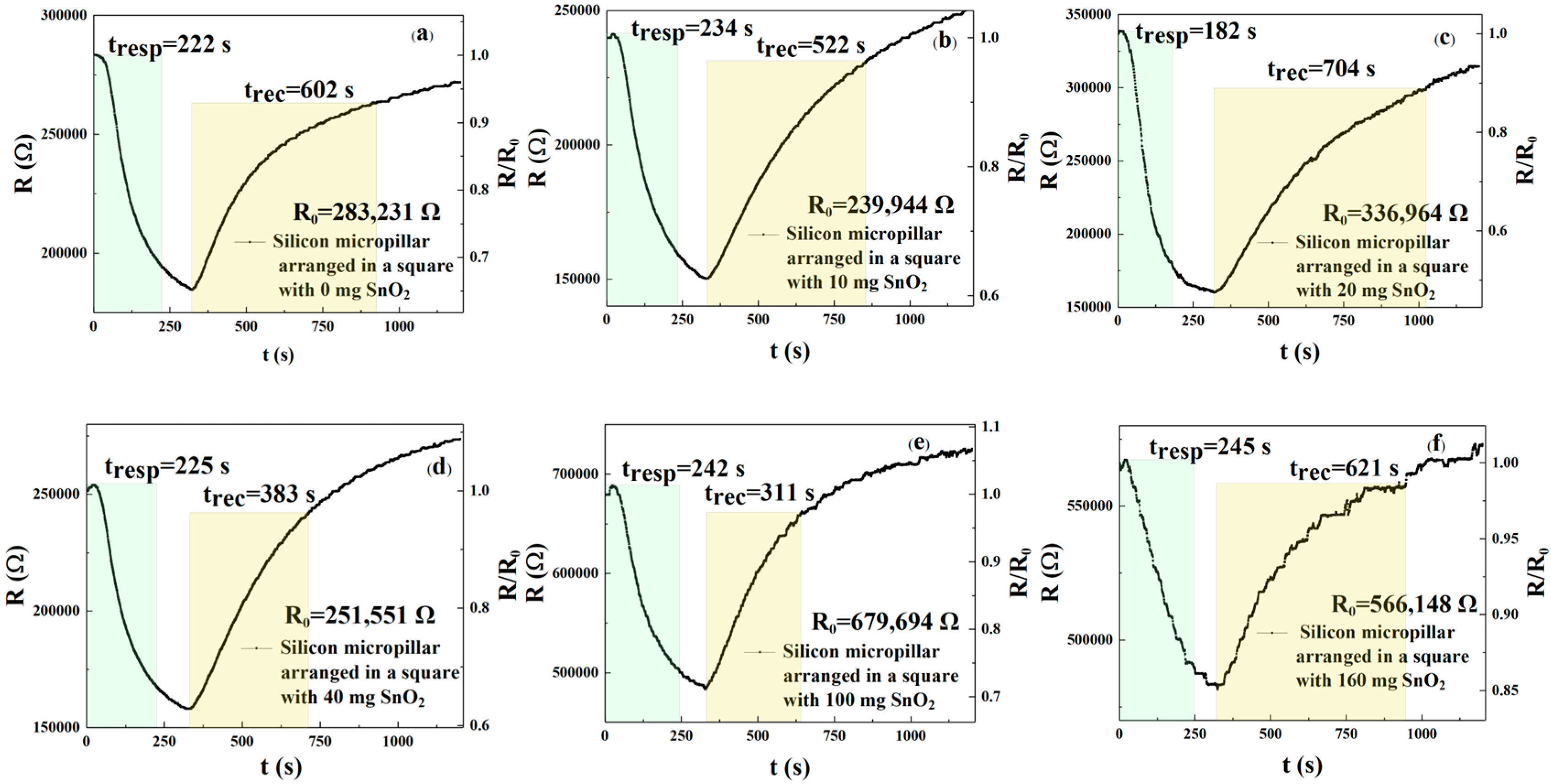

Figure 9a–f and

Table 4 show the response and recovery curves and times of the sensors (square arrangement; three-dimensional column) to 250 ppm NO

2 when sprayed with six different concentrations of rGO/SnO

2. The results show that the response times regarding the six different concentrations are 222, 234, 182, 225, 242, and 245 s, respectively, with recovery times of 602, 522, 704, 383, 311, and 621 s, respectively. According to Formulas (1) and (2), the response times of the m

1, m

2, m

3, m

4, and m

5 sensors were reduced by 9.39%, 4.49%, 25.71%, 8.16%, and 1.22%, respectively, when compared with the m

6 gas sensor, while the recovery times of the m

1, m

2, m

3, m

4, and m

5 sensors were reduced by 3.06%, 15.94%, −13.37%, 38.33%, and 49.92%, respectively. Therefore, the sensor doped with 20 mg shows the best response and recovery speed. The NO

2 response of these six sensors can be calculated from

Figure 9a–f and Formula (3). When the rGO/SnO

2 concentrations were m

1, m

2, m

4, m

5, and m

6, the responsivity values were 1.533, 1.596, 2.101, 1.591, 1.406, and 1.175, respectively. The results show that the sensor with an rGO/SnO

2 concentration of m

3 = 20 mg exhibited the best responsivity compared with m

1, m

2, m

4, m

5, and m

6, respectively. According to Formula (3), the responsivity of the sensor with m

3 = 20 mg improved by 37.05%, 31.64%, 32.06%, 49.43%, and 78.81%, respectively, when compared to the m

1, m

2, m

4, m

5, and m

6 sensors. For square-arranged silicon micropillar sensor surfaces, the m

3 (20 mg) sensors perform best. Next, we investigate whether triangularly arranged silicon micropillars also impact gas detection performance.

In this experiment, we selected a triangular arrangement of micropillars with the same period and diameter as the square arrangement: 14.5 and 6.0 μm, respectively. These were sprayed with different concentrations of rGO/SnO

2 solution.

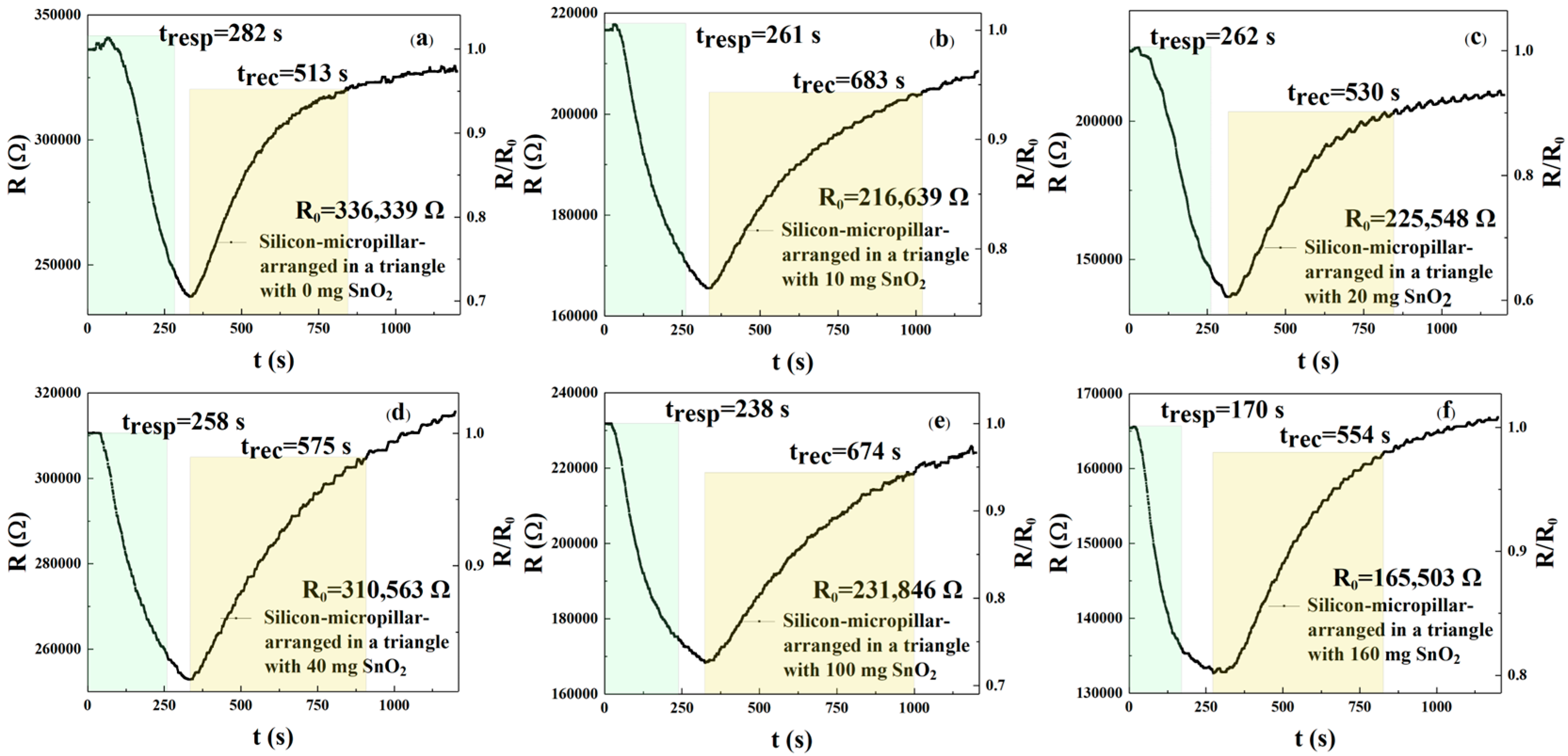

Figure 10a–f show the recovery curves of the sensors’ response to 250 ppm NO

2.

Figure 10a–f and

Table 5 describe the response and recovery curves and times of the described sensors. The results show response times of 282, 261, 262, 258, 238, and 170 s, respectively, and recovery times of 513, 683, 530, 575, 674, and 554 s, respectively, for the six different solution concentrations. According to Formulas (1) and (2), the response time of the m

2, m

3, m

4, m

5, and m

6 sensors was reduced by 7.45%, 7.09%, 8.51%, 15.60%, and 39.72%, respectively, when compared with the m

1 sensor. The recovery times of the m

2, m

3, m

4, m

5, and m

6 sensors were reduced by −33.14%, −3.31%, −12.09%, −31.38%, and −7.99%, respectively. These values indicate that for the triangular arrangement of micropillars, the m

6 = 160 mg sensor shows the best response and recovery speed. The NO

2 response for these six sensors can be calculated from

Figure 10a–f. When the rGO/SnO

2 concentrations were m1, m2, m3, m4, m5, and m6, the response values were 1.417, 1.308, 1.652, 1.228, 1.377, and 1.247, respectively. Based on the above data, sensors with rGO/SnO

2 doping concentrations of m

3 = 20 mg exhibit the best response compared with the m

1, m

2, m

4, m

5, and m

6 sensors, respectively. According to Formula (3), the responsivity of the m

3 = 20 mg sensor increased by 16.58%, 26.30%, 34.53%, 19.97%, and 32.48%, respectively, compared with the m

1, m

2, m

4, m

5, and m

6 gas sensors. It is evident that for a triangular arrangement of micropillars, the 160 mg rGO/SnO

2 concentration (m

6) exhibits the best performance. From the above experimental results, it is clear that the response recovery time of the triangular-arrangement sensor is shorter than that of the square-arrangement sensor. The possible reasons for this are as follows. The triangular arrangement (hexagonal, close-packed structure) has a higher packing density and a more uniform gap distribution than the square arrangement. Therefore, the sensor with a triangular arrangement of silicon micropillars has a larger effective specific surface area, and the formed rGO coating may form a more continuous network, providing more active sites for interaction with NO

2 molecules [

17]. Another possibility is that the triangular arrangement may promote gas diffusion by optimizing gas permeation, enabling the rapid and uniform distribution of gas between the micropillars. This is because the triangular arrangement reduces the tail effect and equalizes the usable concentration downstream of the array, thereby improving the signal and accelerating the rate to a steady state, with a higher response and faster stability [

18].

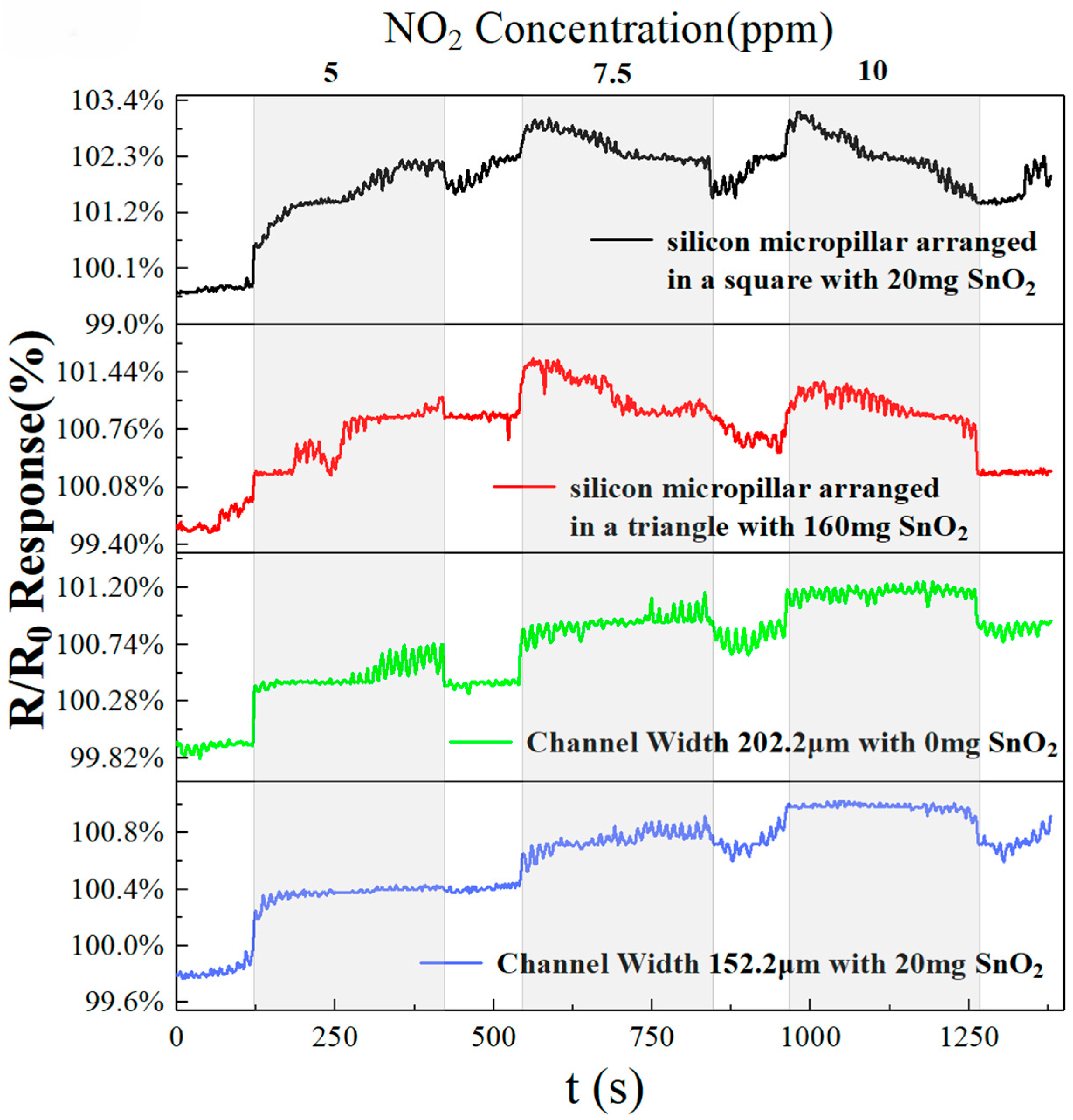

At 40 °C, we selected the best pure rGO sensor, SnO

2-doped sensor, triangle-arranged micropillars sensor, square-arranged micropillars sensor, and interdigital electrode sensor, with the test curve for NO

2 gas shown in

Figure 11. The sensors have similar response and recovery times over a NO

2 concentration range of 5 to 10 ppm. The four optimized sensors all respond to NO

2 gas concentrations of 5, 7.5, and 10 ppm, indicating that the fabricated sensors can also respond at low concentrations. Compared with the other sensors, the pure rGO sensor with a channel width of 202.2 µm exhibits the highest responsivity and shows a distinct recovery curve at 5, 7.5, and 10 ppm. This indicates that at room temperature, the pure rGO sensor with a channel width of 202.2 µm can achieve good response recovery performance for low concentrations of gas.

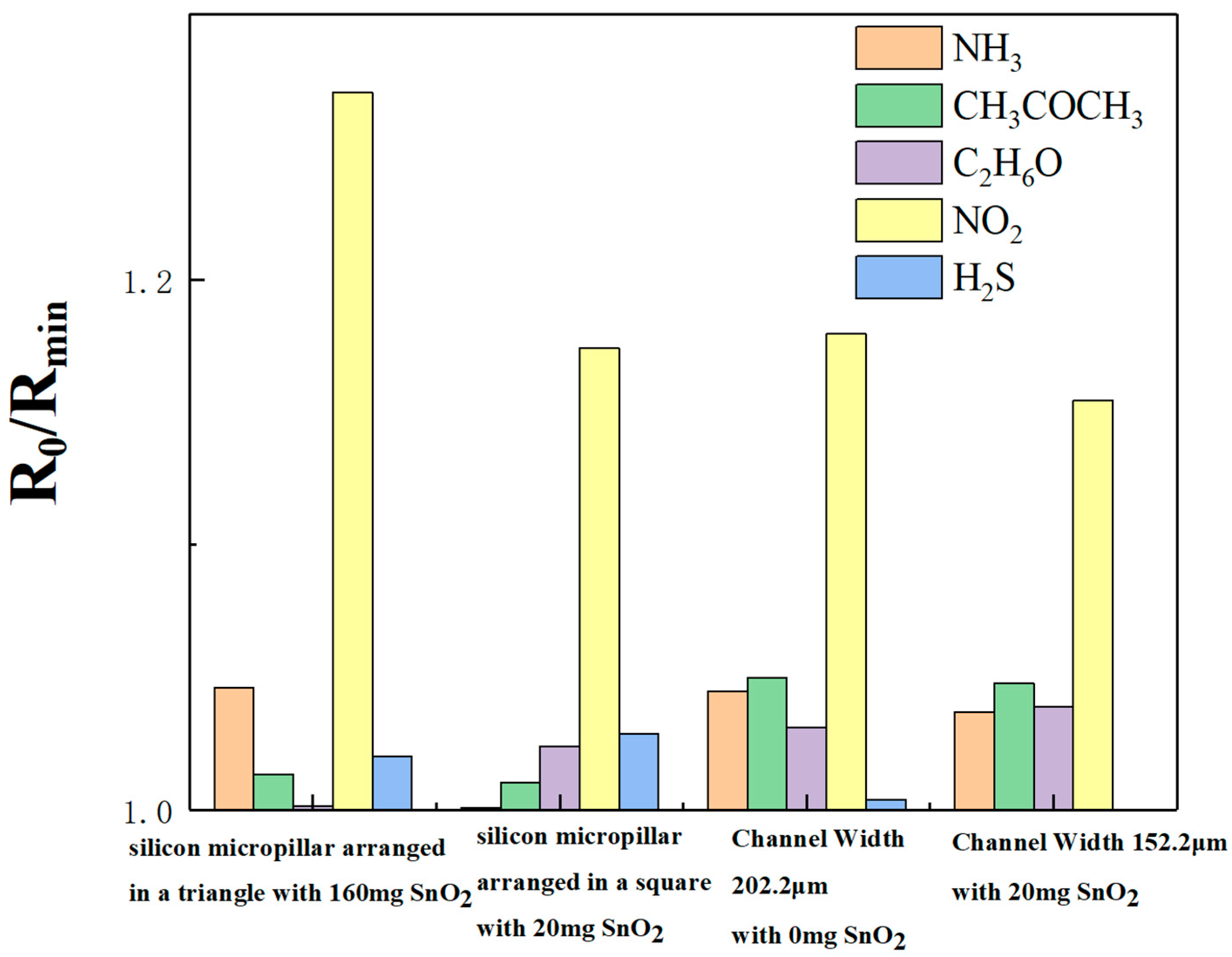

Additionally, the four sensors were tested for gas selectivity, as illustrated in

Figure 12. All the different gases were at a concentration of 50 ppm. Responsivities to NH

3, CH

3COCH

3, C

2H

6O, NO

2, and H

2S for the 160 mg-doped triangle-arranged micropillars sensor were 1.04604, 1.0133, 1.00173, 1.27071, and 1.02014, respectively. According to Formula (3), responsivity to NO

2 increased by 21.48%, 25.40%, 26.85%, and 24.56%, respectively, when compared with NH

3, CH

3COCH

3, C

2H

6O, and H

2S. For the 20 mg-doped square-arranged micropillars sensor, the responsivities were 1.00082, 1.0103, 1.02413, 1.17417, and 1.02891, respectively. According to Formula (3), responsivity to NO

2 increased by 17.32%, 16.22%, 14.65%, and 14.12%, respectively, when compared with NH

3, CH

3COCH

3, C

2H

6O, and H

2S. Responsivities to NH

3, CH

3COCH

3, C

2H

6O, and H

2S for the 0 mg-doped with a width of 202.2 μm sensor were 1.0448, 1.04997, 1.03134, 1.17961, and 1.00408, respectively. According to Formula (3), responsivity to NO

2 increased by 12.90%, 12.35%, 14.38%, and 17.48%, respectively, when compared with NH

3, CH

3COCH

3, C

2H

6O, and H

2S, respectively. Finally, for the 20 mg-doped with a width of 152.2 μm sensor, the responsivities were 1.0371, 1.04789, 1.03909, 1.1545, and 0, respectively. According to Formula (3), responsivity to NO

2 increased by 11.32%, 10.17%, and 11.11%, respectively, when compared with NH

3, CH

3COCH

3, and C

2H

6O,. Based on the above data, when compared with NH

3, CH

3COCH

3, C

2H

6O, and H

2S, the sensors respond significantly more to NO

2 gas, indicating the high selectivity of our sensors for NO

2 gas.

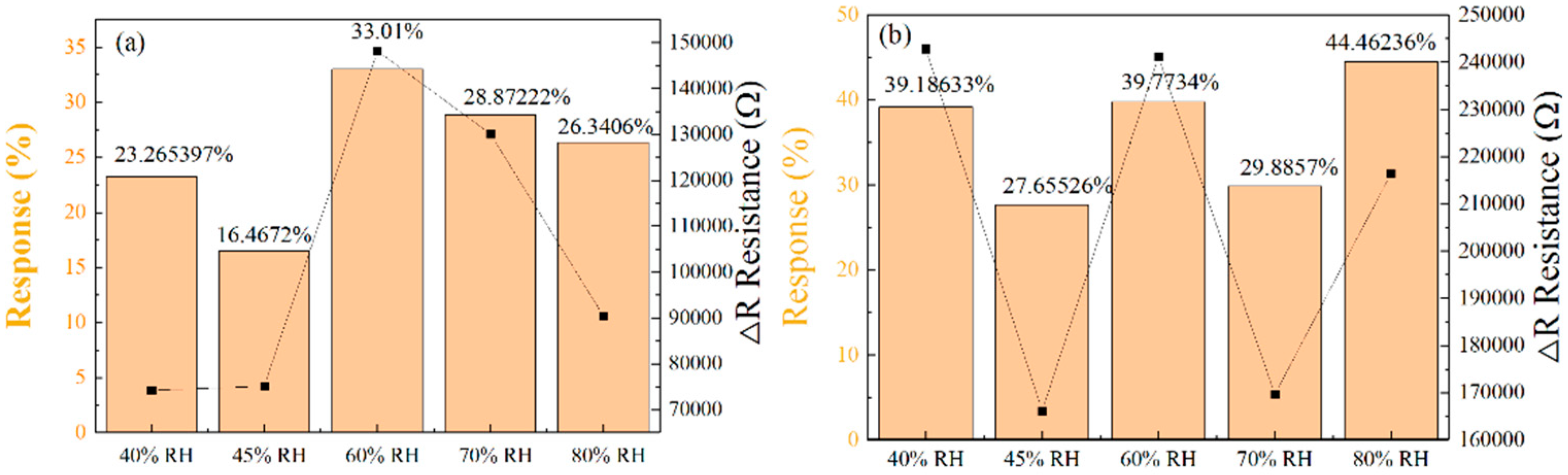

To explore sensor response under different humidity conditions, we subjected the two optimized micropillar sensors to relative humidity environments of 40%, 45%, 60%, 70%, and 80%.

Figure 13a,b show the relative response values of the two sensor types under varying humidity levels, corresponding to the triangular and square arrangements of micropillars, respectively. The sensors’ response to NO

2 was significantly influenced by ambient humidity, exhibiting an initial increase followed by a decrease. At moderate humidity levels, the hydroxyl groups formed by the dissociation of adsorbed surface water acted as proton conductors, promoting NO

2 charge transfer reactions. However, in high-humidity environments, excess water molecules form a physical barrier, preventing NO

2 gas molecules from approaching and adsorbing onto the most critical, highly active sites, resulting in reduced responsivity. A relative humidity of 60% represents the optimal equilibrium point. At this level, the promotional effect of water molecules reaches its maximum, whereby their shielding of active sites has not yet become a significant issue, resulting in the highest response value.

It is interesting to note that in humid environments, the response values of sensors arranged in a square arrangement are higher than those of sensors arranged in a triangular arrangement. The sensors with micropillars in a triangular arrangement showed response values of 23.27%, 16.47%, 33.01%, 28.87%, and 26.34% for 250 ppm NO

2 gas at relative humidities of 40%, 45%, 60%, 70%, and 80%, respectively. In contrast, the sensors with micropillars in a square arrangement demonstrated superior performance, with response values of 39.19%, 27.66%, 39.77%, 29.89%, and 44.46%.

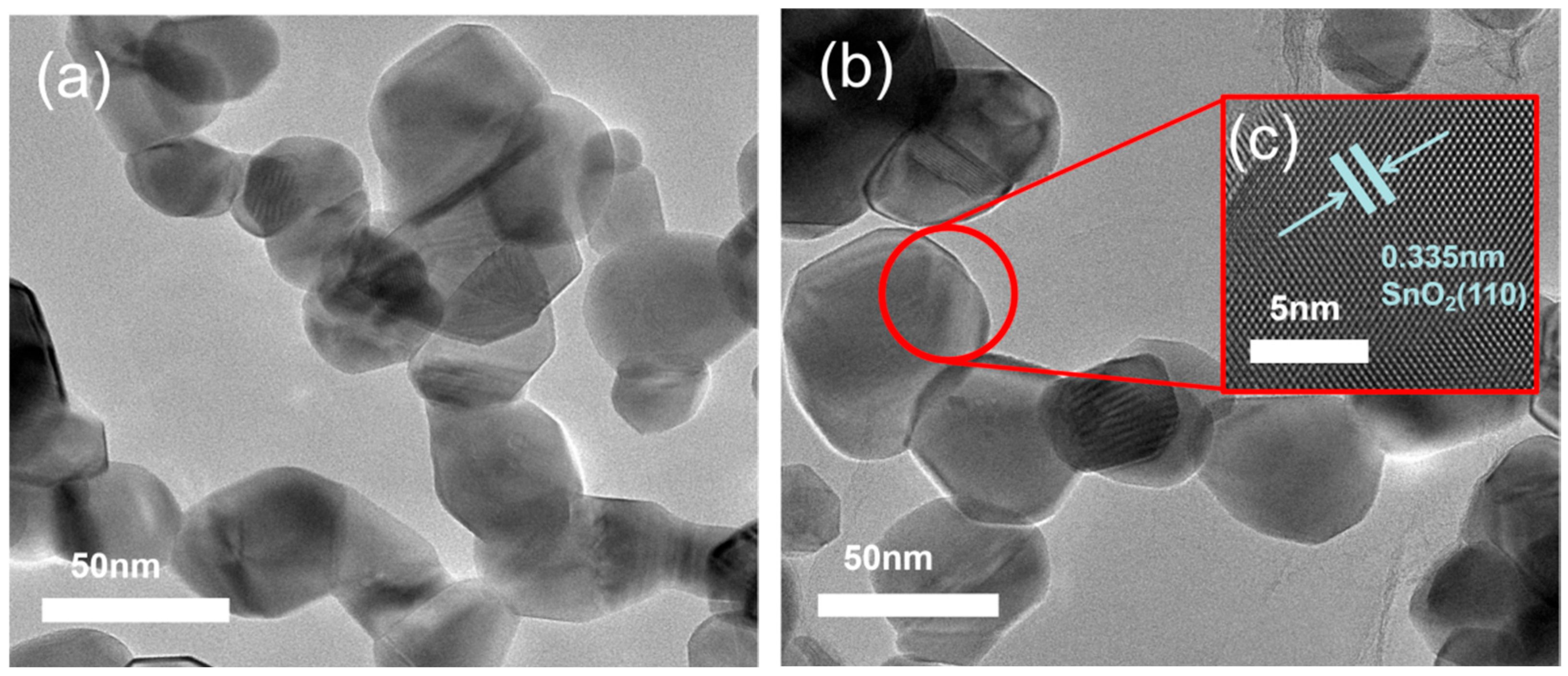

Figure 14a presents a TEM image of pure SnO

2, characterized by the aggregation of numerous small nanoparticles in the dark regions. In contrast,

Figure 14b shows a similar morphology, indicating a uniform dispersion of SnO

2 nanoparticles on the rGO sheets. Furthermore, the HRTEM image in

Figure 14c reveals well-defined lattice fringes with an interplanar spacing of 0.335 nm, corresponding to the (110) crystal plane of SnO

2, providing further evidence of successful composite formation.

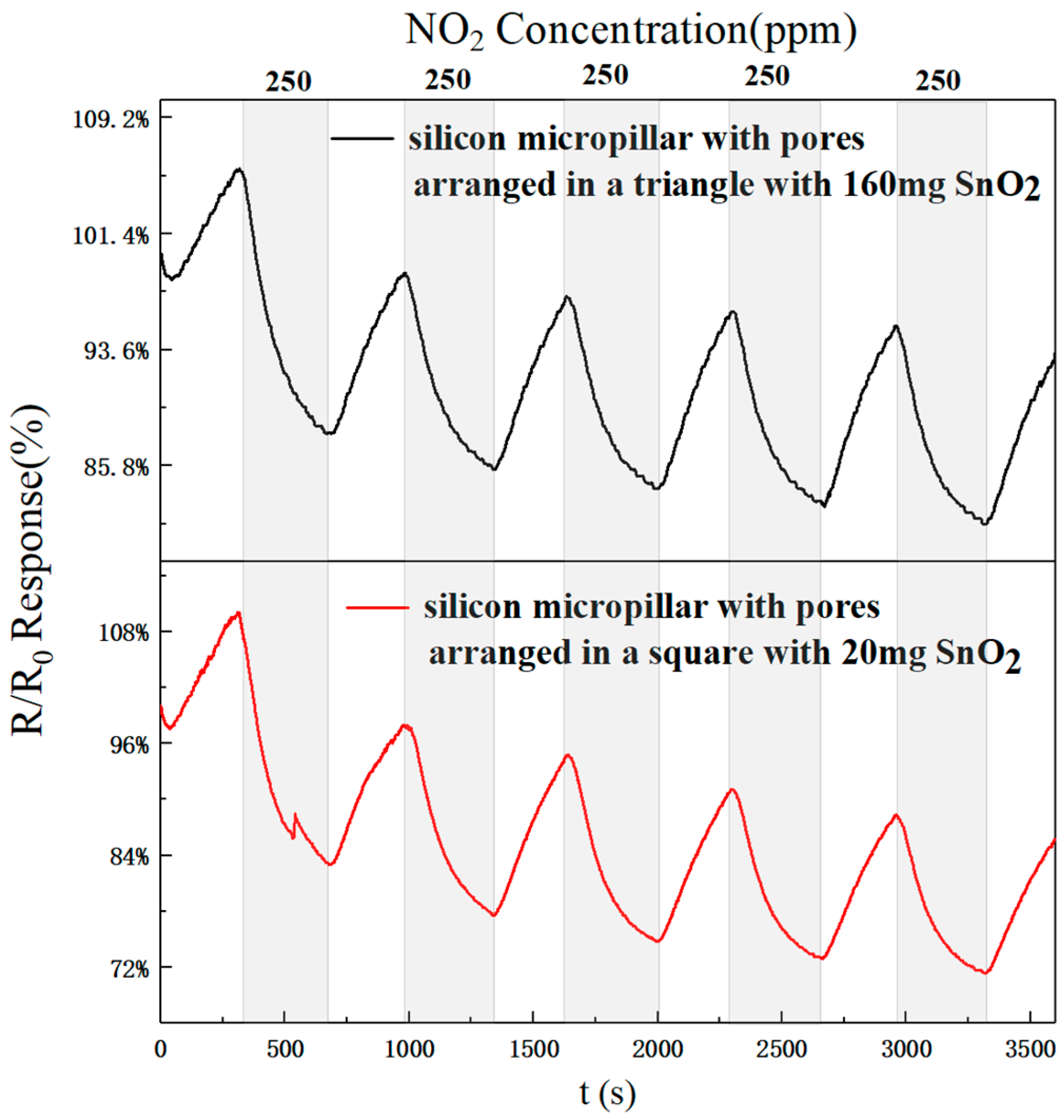

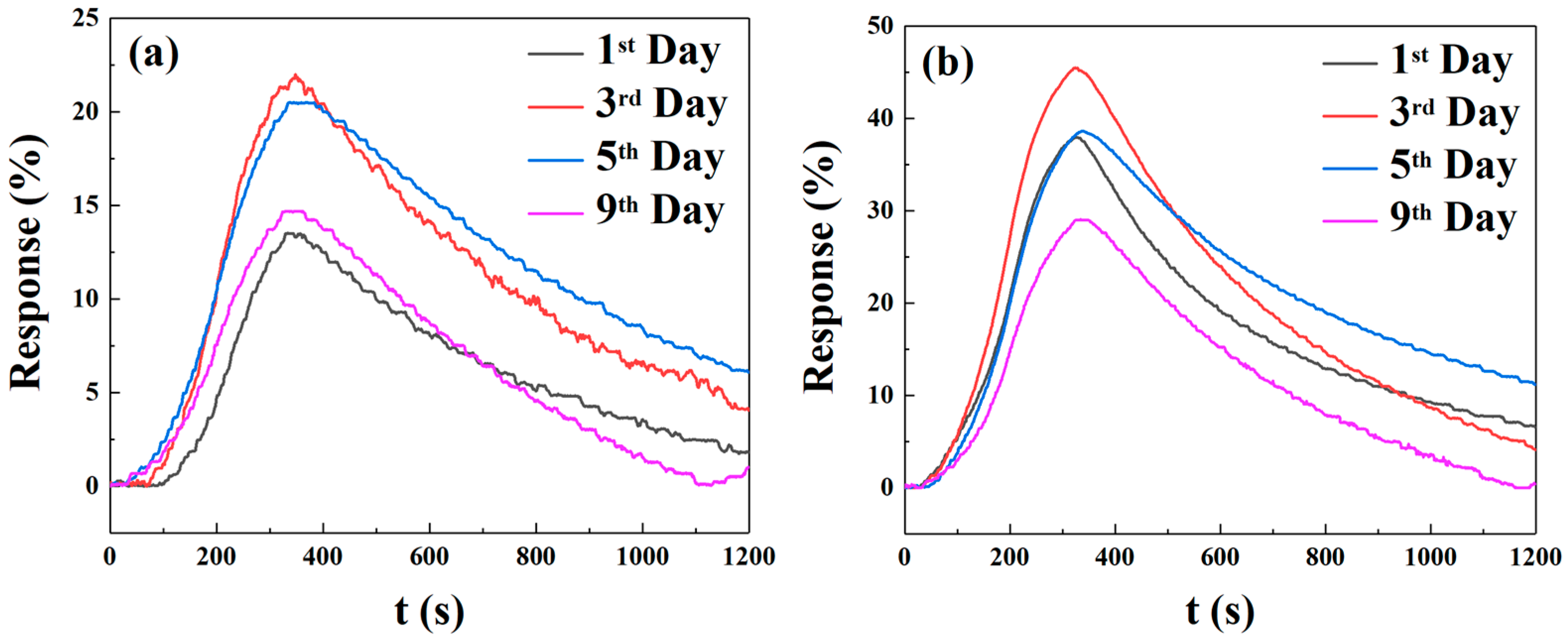

Figure 15 shows the results of five cycles of 250 ppm NO

2 for the more responsive sensors (triangular and square micropillar arrays). The response value remains relatively unchanged, indicating that the sensors exhibit good repeatability. To ensure the temporal stability of the test results, we selected four time points: the first, third, fifth, and ninth days. We conducted response tests for two micropillar array types of gas sensors with a target gas concentration of 250 ppm NO

2, as shown in

Figure 16. We define the “response value” as follows:

R

g is the current resistance, and R

a is the initial resistance [

5]. The highest response values of the triangular micropillar array gas sensors at the four time points are 13.531%, 22.004%, 20.495%, and 14.700%, respectively. The response on the third day is higher than that on the first, fifth, and ninth days by 62.62%, 7.36%, and 49.69%, respectively. The highest response values of the square micropillar array gas sensors at the four time points are 37.975%, 45.447%, 38.628%, and 29.076%, respectively. The response on the third day is higher than that on the first, fifth, and ninth days by 19.68%, 17.65%, and 56.30%, respectively. From the above results, it is obvious that both types of gas sensors reached their highest response values on the third day. The optimized sensors in this work demonstrate substantially superior performance to the value of 13.27 reported in [

12] for 300 ppm NO

2, even at a lower detection concentration of 250 ppm. The responses of both optimized sensors exceeded the value reported in the reference. Notably, the 20 mg-doped square micropillar array sensor achieved optimal response values ranging from 29.17 to 45.47 over different testing days, confirming a significant enhancement in response.

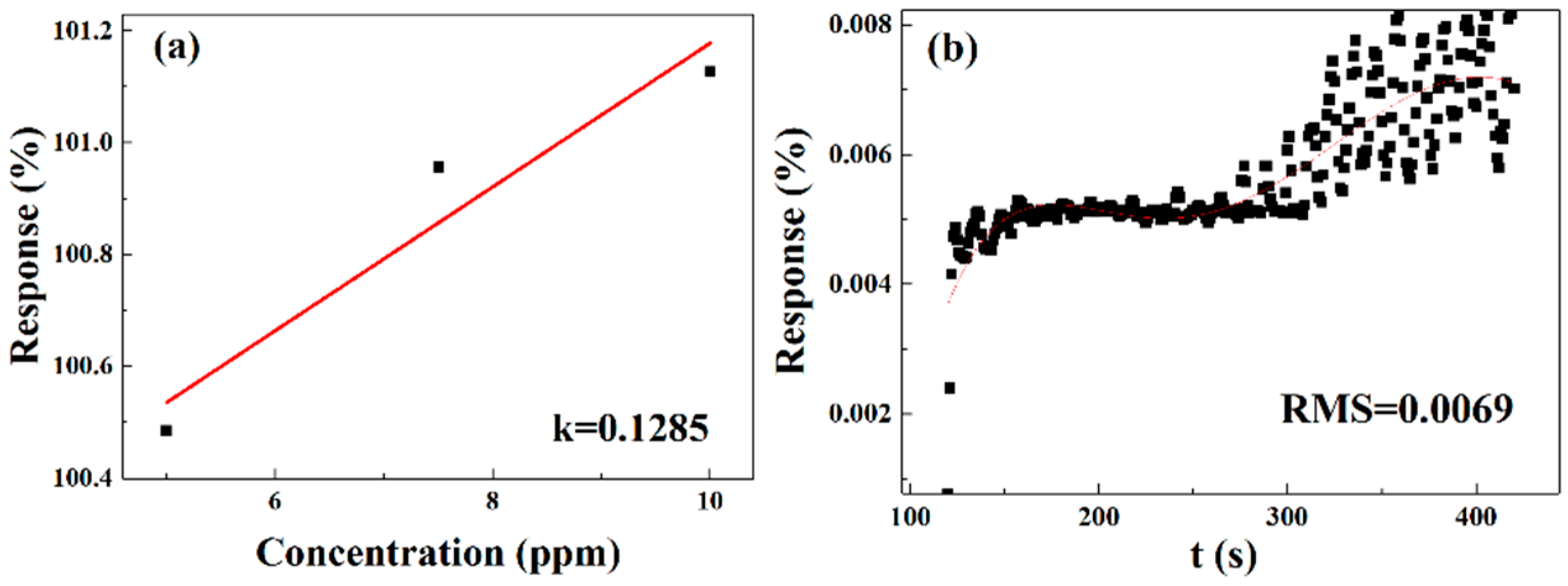

We define the “limit of detection” as follows:

Slope k can be obtained by linear fitting (

Figure 17a), and the root mean square (RMS) can be calculated using the fifth polynomial linear fitting analysis of the baseline data of the 0 mg-doped and 202.2 μm-width gas sensor (

Figure 17b). Finally, the theoretical LOD of the gas sensor was calculated to be 0.161089 ppm [

19].