1. Introduction

In cities where winter snowfall scenarios are common, ice, heavy snow, sleet, and snow accumulation obstruct roadways, lanes, sidewalks, and traffic signals. This reduces mobility, increases travel time, and results in less-than-ideal visual conditions [

1]. Snow affects the stability of the environment [

2], causing changes in road structure and context by creating additional lane-like lines and areas within and near road boundaries [

3]. Autonomous vehicles (AVs), advanced driving-assistance systems (ADASs), and human drivers face significant challenges in these extreme environmental conditions, as they struggle to accurately detect obstacles, interpret scene features, identify drivable areas, and maintain the correct lane [

4,

5].

Lane detection is critical for estimating vehicle position and trajectory relative to the road. It requires models capable of achieving high detection rates under diverse environmental conditions [

6,

7]. Both model-based [

8,

9,

10] and deep learning-based approaches [

1,

11,

12,

13,

14] have been proposed. However, lane perception algorithms degrade significantly under winter conditions. Ice, snowflakes, and fog distort sensor data, reducing accuracy and reliability [

3]. For instance, LaneATT [

15], an object detection-based method that uses an anchor-based attention mechanism to aggregate global information, experiences a 41.3% drop in F1 score under snow-like scenarios, where lane markings are absent or difficult to distinguish. CLRNet [

16], a method that uses a cross-layer refinement network, drops 40.1% under these conditions, and UltraFast Deep Lane Detection (UFLD) [

17], a method designed for challenging scenarios that represents lanes with anchor-based coordinates and learns them through classification, falls by 43.3%. This sensor and algorithm degradation increases the risk of incorrect vehicle decisions, crashes, and energy inefficiency [

18].

Winter road conditions also impair human drivers’ lane-keeping performance by reducing lane boundary visibility, increasing fatigue and decreasing concentration [

4,

19,

20]. Furthermore, confidence in AVs and ADASs may decline if technology fails under snowy conditions. Even without snow, user trust in these systems is often low; many users already show apprehension due to unfamiliarity or reported accidents. Surveys report that many potential users fear (66%) or are unsure (25%) about driving fully autonomous cars [

21]. According to the American Automobile Association [

22], trust improves when users receive training and guidance on how to operate AVs and ADASs.

Lane detection methods must be improved and adapted to winter conditions from both technical and human-centered perspectives. However, this requires extensive evaluation prior to implementation [

23]. Real-world testing is challenging due to cost, safety risks, and ethical considerations [

24,

25]. Simulation provides a safe, realistic, and customizable alternative [

24,

26]. Technically, simulation has been used for data collection for training and validation of lane detection algorithms [

27,

28], systematic testing of lane-change behaviors [

23], evaluation of shadow pattern-induced vulnerabilities and mitigation strategies in lane detectors [

29], and analysis of perception systems under variations in sensors, lighting, and weather [

30]. Human-centered studies employ simulation to assess lane-change performance [

31], user reactions to takeover requests during non-driving tasks [

32], unsafe driving behaviors [

24], and user feedback interfaces that enhance situational awareness [

33]. They have also been used to teach drivers how to interact with AVs and react to unpredictable and dangerous situations [

34], and to increase trust and acceptance of AVs and ADASs through tasks such as lane changes or autonomous parking [

35].

Most studies on autonomous driving and human–driver interaction are conducted in daytime and mild or temperate weather conditions, limiting discovery of new design requirements and potential solutions [

36]. Environmental and road factors, and their impact on drivers’ experience, performance, AV/ADAS acceptance, and intention to use, remain understudied [

37,

38]. Evaluating more challenging scenarios is therefore essential to achieve a comprehensive understanding of these aspects and drivers’ responses under complex conditions [

24].

Despite advances in lane detection methods, their severe performance degradation under snow (~40% drop in F1) combined with limited knowledge on drivers’ acceptance, user experience, and interaction with such ADASs under adverse conditions highlights a critical research gap. Addressing this requires safe, controlled, and immersive testing environments, such as virtual reality (VR) simulators [

24,

26], which allow exploration of both technical and human factors without compromising safety.

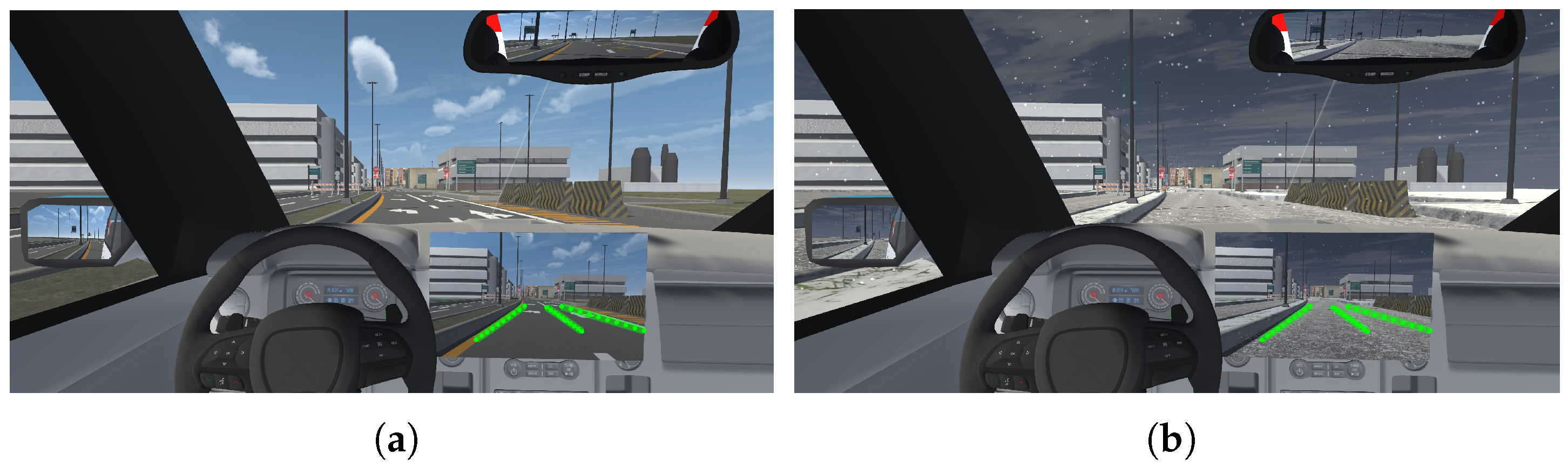

Building on previous work [

39,

40] where we developed a vision- and deep learning-based approach to improve lane detection on snowy roads, this paper presents a human-in-the-loop validation of winter lane detection using VR. Users’ lane-keeping performance, experience, and effectiveness of lane feedback user interfaces are evaluated in a safe, controlled, immersive, and interactive snowy driving simulation environment, monitoring variables such as heart rate, cognitive load, and vehicle-wheel contact with lane lines. Results show that the winter lane detection approach improves users’ lane-keeping performance, driving experience, and confidence under extreme winter conditions.

The contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

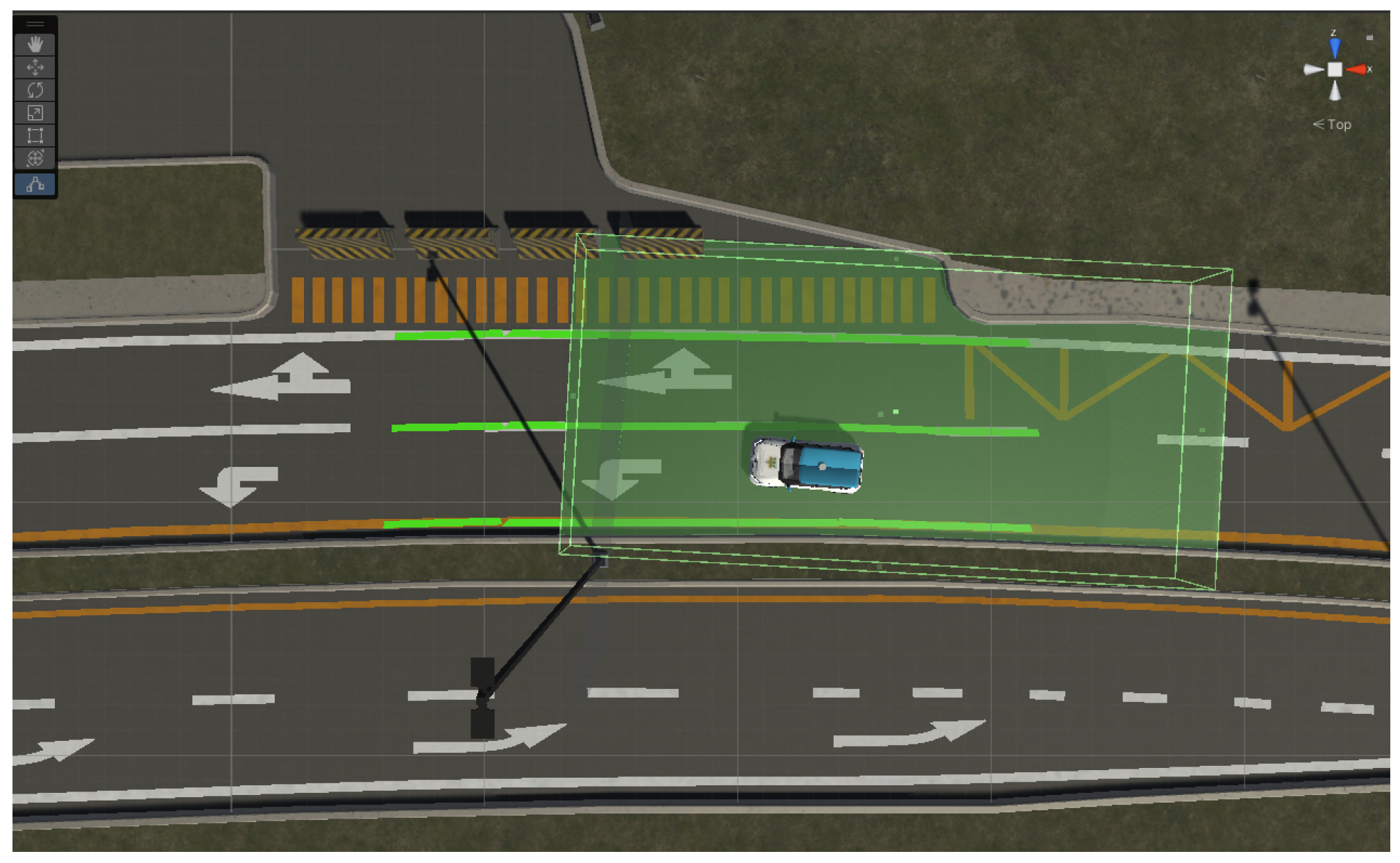

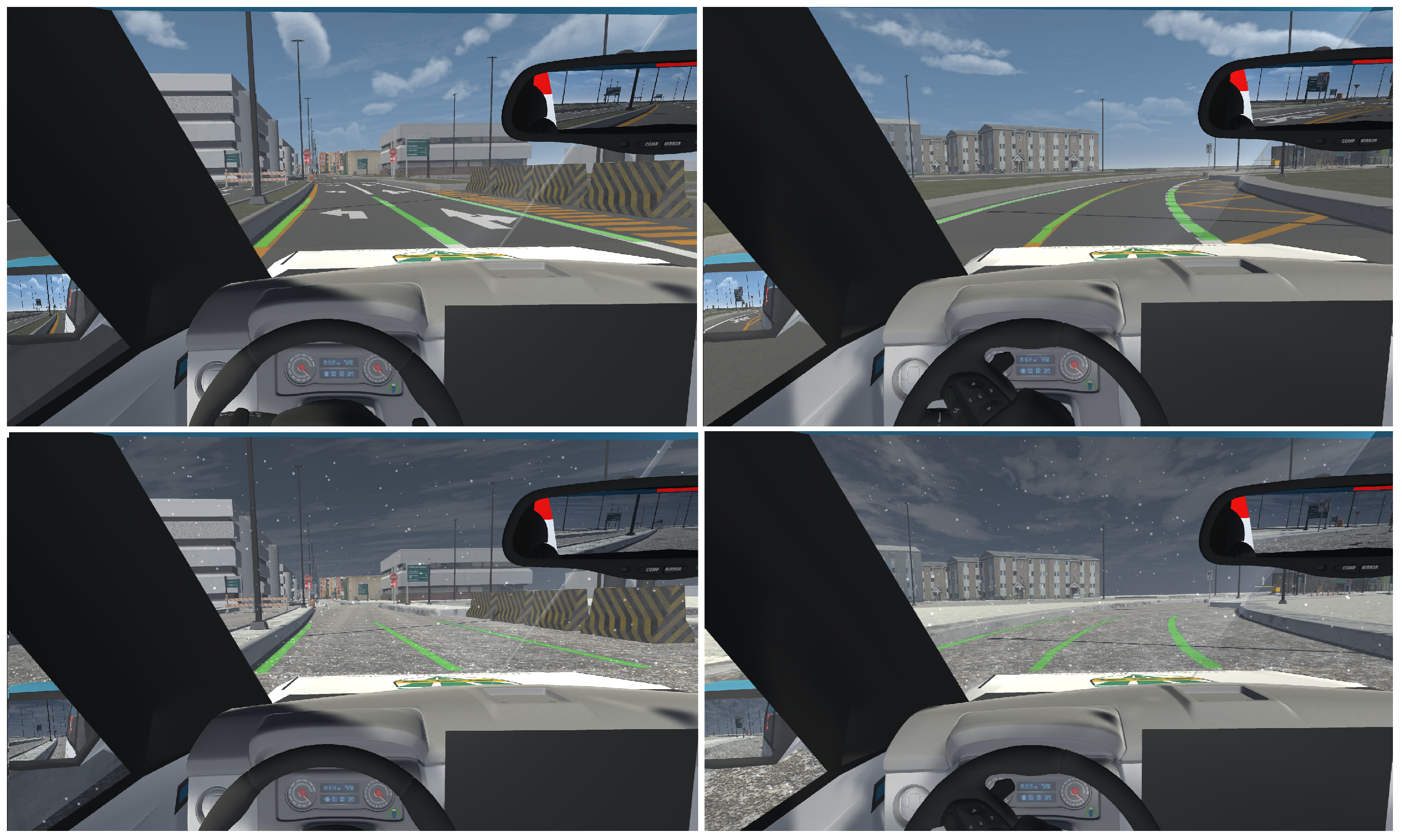

Low-cost virtual simulator-based evaluation in snowy conditions: We present a cost-effective virtual road environment that supports the integration and validation of vision-based lane detection algorithms in mild and snowy conditions, covering the full pipeline from virtual sensor data capture to lane visualization in a simulated vehicle. The platform also enables safe, immersive, and controlled user testing, not only allowing preliminary ADAS performance assessment but also enabling drivers to experience firsthand the benefits and practical usefulness of lane detection in challenging scenarios like snowy roads, fostering trust, acceptance, and familiarity with such systems.

Influence of snow on driving performance and the role of lane detection systems: We analyze how snowy conditions affect drivers’ lane-keeping performance and user experience, and demonstrate the advantages of lane detectors adapted to these challenging conditions.

User feedback on lane information presentation: The study provides insights into users’ preferences regarding lane information feedback, offering valuable data that can serve as a reference for future adaptations in real vehicles and the design of driver interfaces.

4. Experimental Design

We conducted a preliminary user study adopting a human-centered mixed experimental approach, combining quantitative physiological and performance measures during driving with qualitative measures of trust, acceptance, and user experience regarding the lane detector system in snowy road conditions.

4.1. Ethical Approval

The study protocol involving human participants was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières (Certificate No. CER-24-310-07.04) on 22 October 2024. Subsequent modifications to the protocol were also reviewed and approved under Certificate No. CER-25-324-08-01.11. Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. All physiological data collected were anonymized and securely stored to ensure participant privacy and confidentiality, in accordance with the committee’s requirements.

4.2. Participants

Fifteen volunteers participated in the experiment, with a wide range of driving experience, with an overall average of 12.13 years of driving (SD = 13.95). Of the sample, 40% had been driving for 10 years or more. Regarding the accident history, 40% of the participants reported having been involved in one or more traffic accidents. The familiarity of the participants with driving on snow-covered roads was limited, with only 20% having driven under such conditions.

Participant ages ranged from 19 to 64 years, with an average age of 32.9 years (SD = 15.7). Of the participants, 53.3% were older than 28 years and 46.7% were younger. The gender distribution was unbalanced, with 86.7% male and 13.3% female.

Regarding contact with autonomous systems, one participant reported having driven such a vehicle (7%), and two said that they had only had contact with them (13%). The remaining participants (80%) had neither driven nor had contact with autonomous vehicles. In contrast, participants’ familiarity with ADASs was much higher, with 60% of participants having used such systems and 7% having only had contact with them.

This resulted in a heterogeneous sample with varying levels of driving experience, age, education, and exposure to ADASs and autonomous systems, all with sufficient competence to carry out the experimental tasks.

4.3. Planning

We implemented a

factorial repeated-measures design with two within-subjects factors: lane detector (activated or deactivated) and snow (present or absent on the road). Each participant completed the four scenarios described in

Table 1 by driving along a designated UQTR circuit. The circuit was 950 m long, with an approximate duration of 5 min per trial. The route map was presented to the participants prior to the experiment and was also displayed on the central console user interface as guidance during the virtual driving task.

For situations involving the lane detector, the three user interfaces implemented for lane visualization were activated sequentially along the circuit so that participants could evaluate them and give us their opinion. The activation of the interfaces throughout the test circuit is illustrated in

Figure 12.

4.4. Procedure

The duration of the experiment was approximately 55 min per participant, of which 25 min was spent on driving within the virtual environment. The experiment was conducted in a single session for each participant.

Stages of the Experiment

Reception and characterization of the participants:

At the beginning of the experimental session, the participants were welcomed and briefed on the objectives and procedures of the study, and asked to sign an informed consent form. All participants agreed to participate. Subsequently, participants completed two preliminary questionnaires. The first gathered sociodemographic information and assessed their prior experience with ADASs and automated driving systems. The second questionnaire evaluated their level of technological acceptance regarding lane detection systems.

Presentation of the test and control devices:

At this stage, participants were introduced to the test to be performed and the devices to be used for interacting with the simulator. They were then given time to familiarize themselves with the virtual environment and the vehicle controls. An overview of the experimental setup, with one of the participants during the test, is presented in

Figure 13.

Driving experience in the virtual environment:

The participant undergoes the driving experience following the indicated trajectory within the virtual environment in the different driving situations. The order of the situations was counterbalanced using a Latin square to minimize order effects.

End of the session:

At the end of the driving experience, participants completed a series of questionnaires about their driving experience, their level of acceptance of the lane detection system, their confidence in it, and the feedback interfaces.

4.5. Metrics

We conducted quantitative and qualitative measurements to evaluate the impact of winter driving conditions and a lane detection system on driving performance, experience, technology acceptance, and user confidence during the driving situations described above.

To assess participants’ physiological responses across scenarios, we recorded heart rate and cognitive load using the VR headset in each situation.

Table 2 provides a description of the monitored signals [

95]. Driving performance was evaluated in Unity 3D by measuring the number of times participants unintentionally departed from their lane. All data were stored in log files for subsequent analysis.

In addition, various questionnaires were administered to participants to assess the aforementioned impact:

Sociodemographic questionnaire: driving experience (years), age, sex, nationality, education level, and experience with ADASs and automated driving systems.

Initial questionnaire on the acceptance of lane detection systems [

56,

96,

97].

Driving experience questionnaire (ease of use, acceptance, and user experience) [

98,

99,

100,

101].

Questionnaire on confidence in lane detection [

102].

5. Results and Discussion

In this section, we present the results of the preliminary user study. We analyze the data obtained to assess whether the use of a lane detection system and winter driving conditions have a direct impact on lane-keeping task performance, as well as on user experience and the trust and acceptance of this type of ADAS. Although the sample size is limited, the results provide insights into the effectiveness of the lane detection system in snowy winter conditions, both in terms of performance and user experience, as well as into the user feedback interfaces.

After starting the driving experience, two participants experienced symptoms of dizziness due to the VR headset and therefore decided not to continue the tests. The results presented below correspond to the remaining participants.

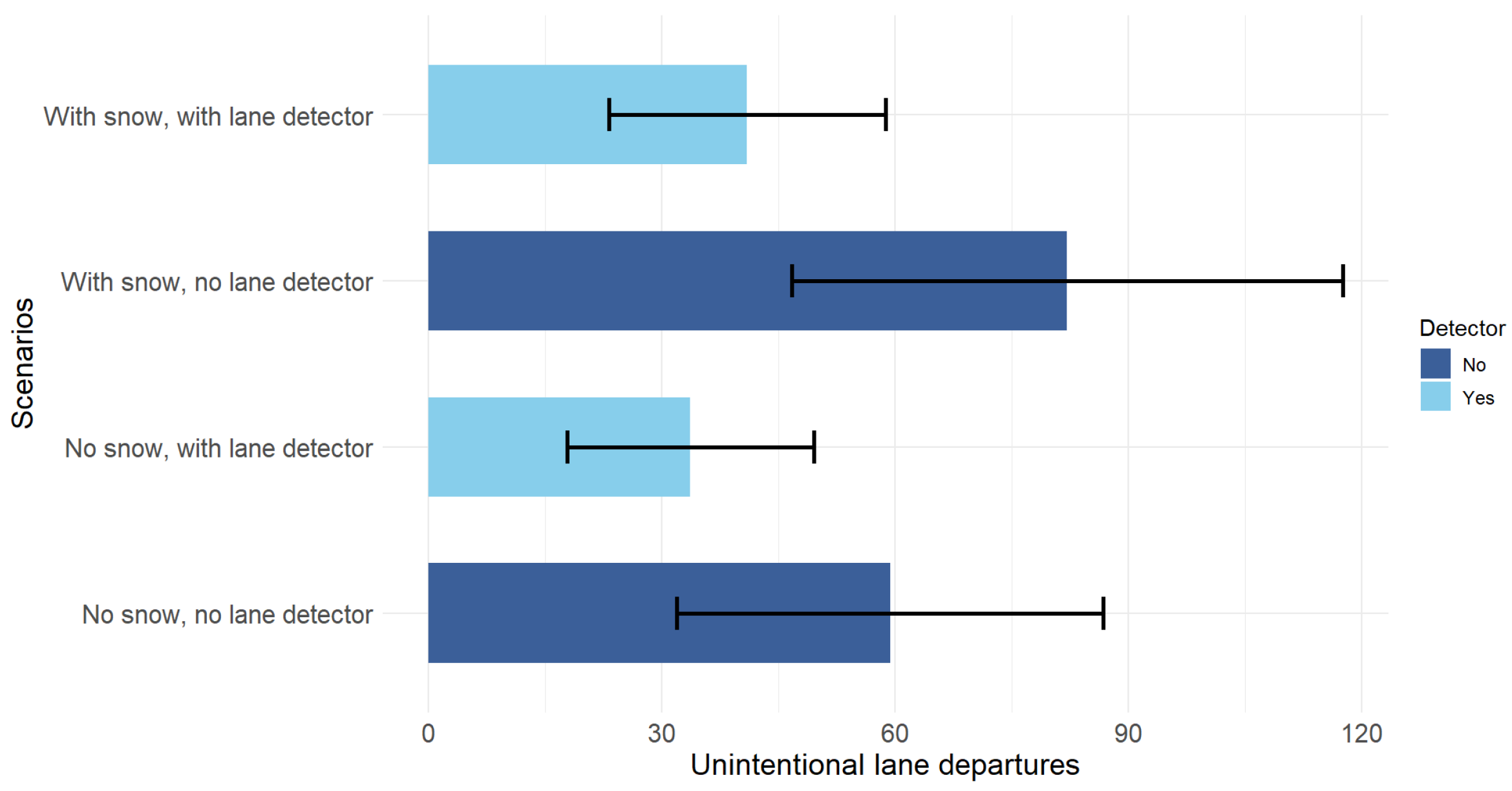

5.1. Driving Performance

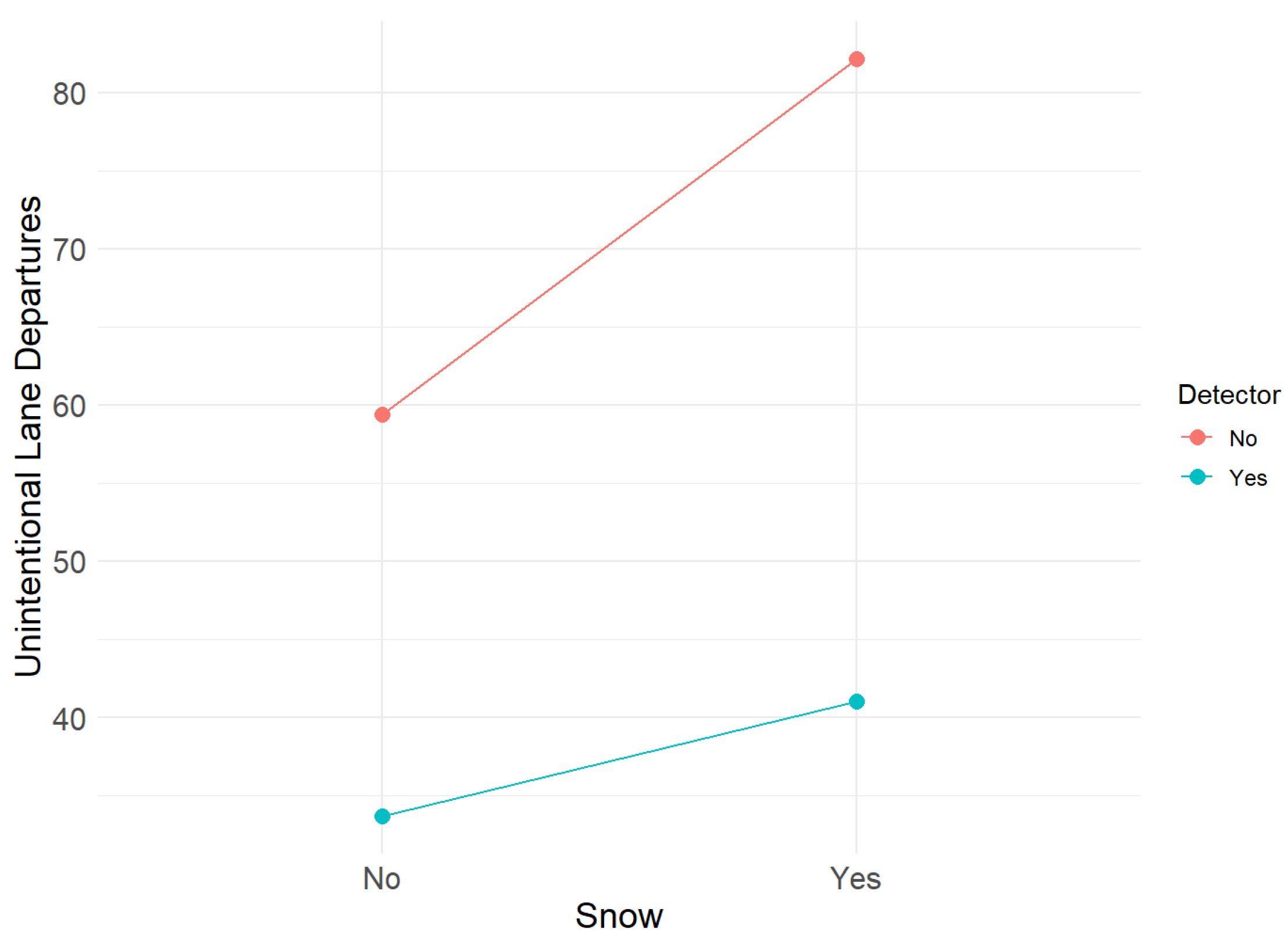

We performed a one-way ANOVA to analyze participant performance based on the number of unintentional lane departures, evaluating overall differences between the four driving scenarios. A significant effect of the scenario on the performance was found F(3,48) = 3.45,

p = 0.024. Tukey’s post hoc tests showed that significantly more lane departures were made in the snowy road scenario without the detector, compared to the snow-free road condition with this system (diff = 48.46;

p = 0.025). The comparison between the snowy road scenarios with and without the lane detector showed a trend toward fewer lane departures when the detector was activated (

p = 0.073), with approximately 41 fewer errors on average, as shown in

Figure 14. Although this effect did not reach the conventional threshold for statistical significance (

= 0.05), the magnitude of the difference indicates a potential practical benefit of the lane detection system in snowy driving conditions in terms of lane keeping. A larger sample size would be necessary to confirm this effect with greater statistical power. No significant differences were observed among the other comparisons.

Subsequently, to specifically explore the separate effects of the detector, the presence or absence of snow on the road, and their interaction on the number of unintentional lane departures, we performed a two-way ANOVA with a two-by-two factorial design. A significant main effect of detector use was found (F(1,48) = 8.24,

p = 0.006), with fewer lane departures when the detector was turned on. The sole presence or absence of snow on the road did not have a significant effect (F(1,48) = 1.67,

p = 0.2). The interaction between snow and the detector was also not significant (F(1,48) = 0.44,

p = 0.51), highlighting that the positive effect of the detector does not depend on the presence of snow. In both environmental conditions, lane departures are consistently reduced with the activation of this ADAS, significantly improving the performance of participants. The snow x detector interaction graph for erroneous lane departures in

Figure 15 illustrates the observed trends. Although snow and interaction were not statistically significant, visual inspection suggests that the presence of snow on the road tends to increase the number of wrong-lane departures, especially when the detector is deactivated. The lane detector dampens the negative effect of snow [

103,

104,

105].

5.2. Physiological Response

To evaluate the participants’ physiological response to different driving situations, we recorded their cognitive load and heart rate during these situations using the VR headset, and compared the values obtained with a one-way ANOVA and a repeated-measures ANOVA.

Missing data were particularly present in physiological measurements due to the technical limitations of the VR headset, whose sensor accuracy was affected by unstable contact, sweat, or cosmetic interference. Given the small size of our sample (N = 15), listwise deletion would have further reduced statistical power and potentially introduced bias by disproportionately excluding participants with missing values. Mean substitution or single imputation approaches were also deemed inappropriate, as they tend to distort variance and underestimate uncertainty. Multiple imputation, despite the small dataset, provides a more principled way to handle missingness, as it preserves variability, accounts for the uncertainty of missing values, and avoids the loss of cases.

Therefore, we opted to perform multiple imputation using the mice package in R [

106]. Thus, we generated five imputations using the predictive mean matching (pmm) method, which we combined to obtain a complete dataset and perform the corresponding analyses. The pmm method was used because it is particularly robust with small samples, as it imputes observed values from similar cases rather than generating purely model-based estimates. This approach is also well-suited when the variables may deviate from normality, as it does not assume a specific distribution and better preserves the variability of the original data [

106,

107].

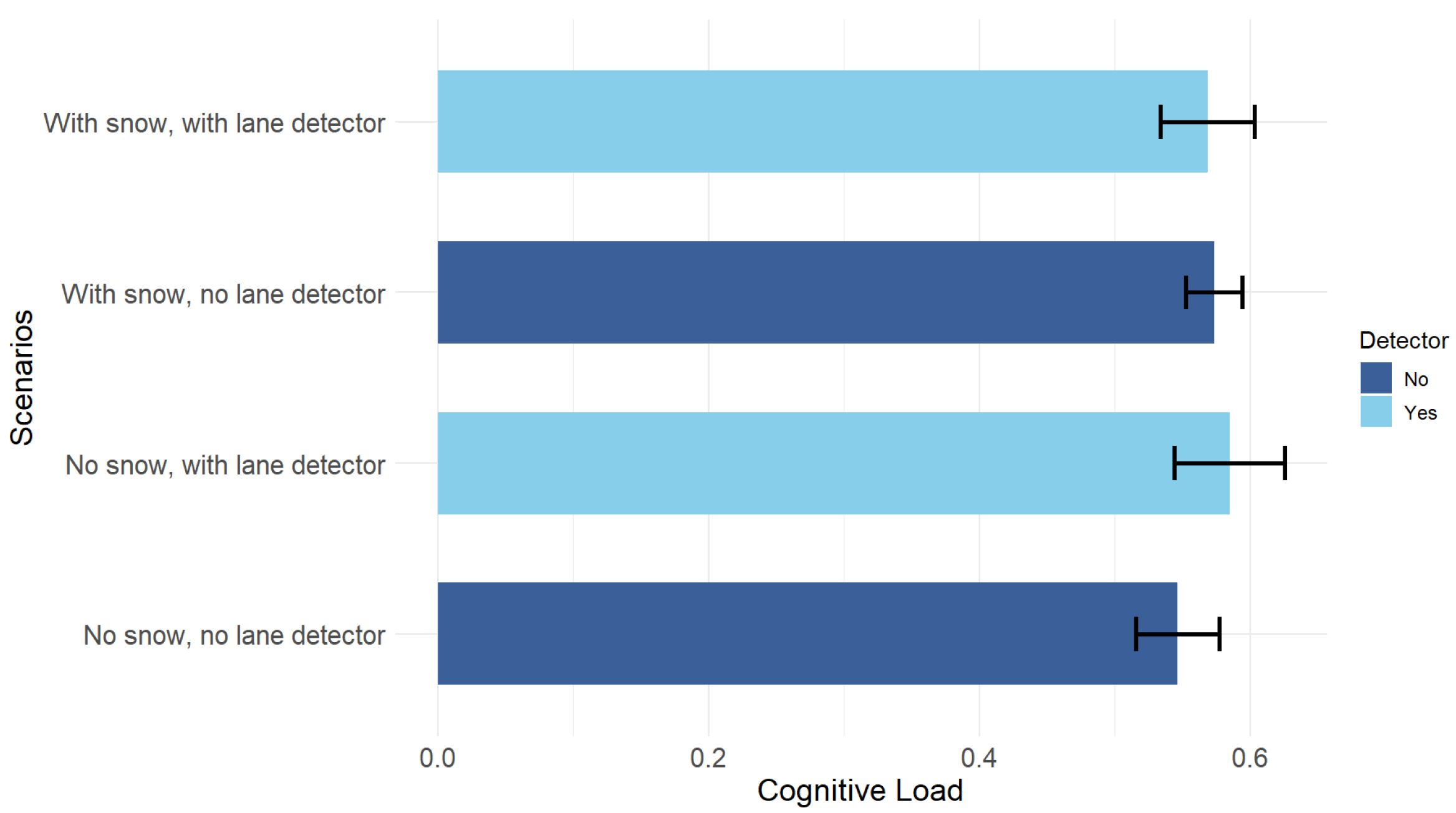

5.2.1. Cognitive Load

Univariate analysis of variance showed that the effect of the four scenarios on cognitive load was not significant (F(3,48) = 1.15,

p = 0.34).

Figure 16 shows the means of cognitive load per scenario, noting that these do not differ in a statistically detectable way.

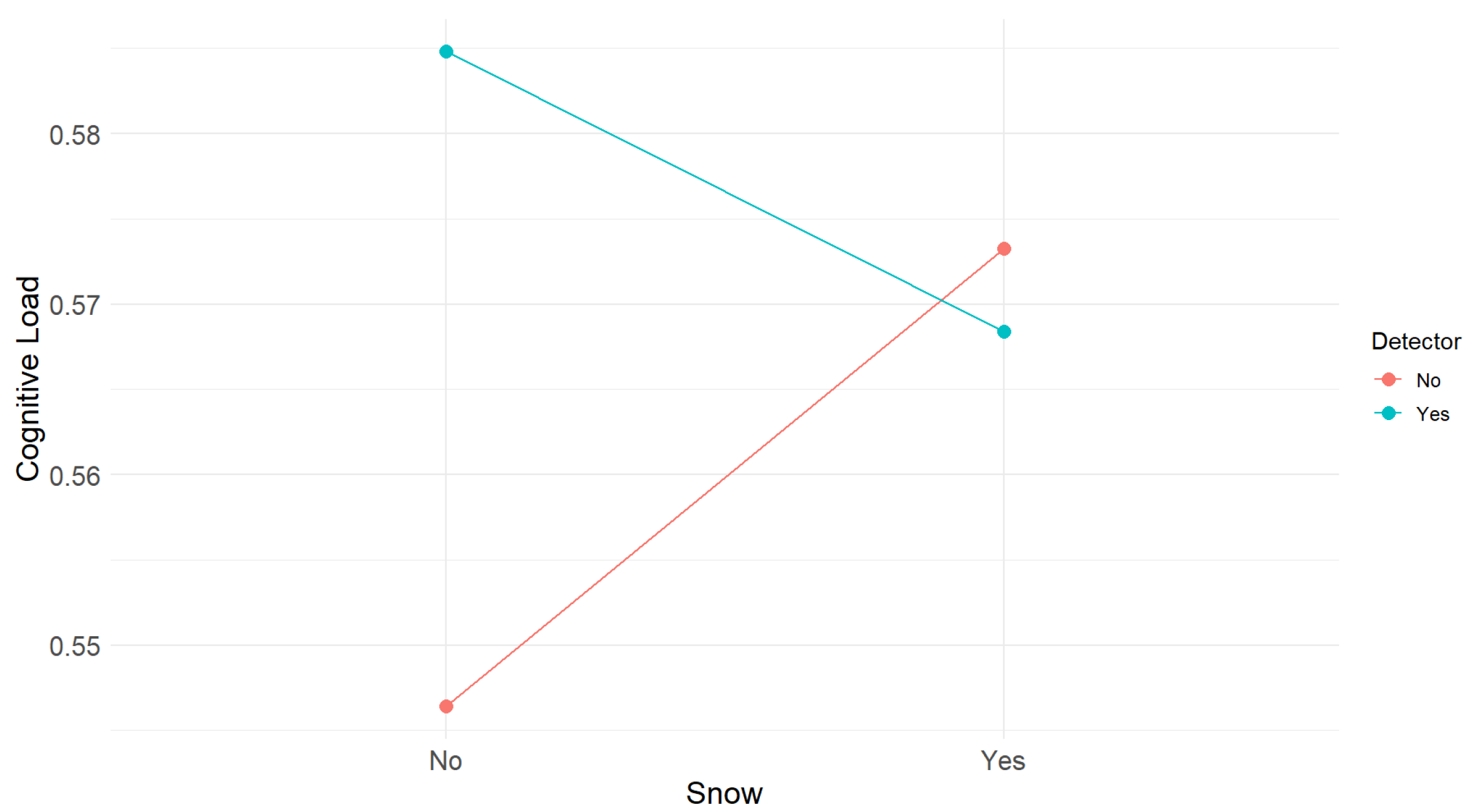

The

ANOVA revealed that there were no main effects of the detector (F(1,48) = 1.25,

p = 0.27) or presence or absence of snow (F(1,48) = 0.12,

p = 0.73) on cognitive load. A trend toward snow × detector interaction was observed (F(1,48) = 2.08,

p = 0.16), although this also did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 17 shows the snow × detector interaction for cognitive load.

On average, participants showed moderate cognitive load in all driving conditions (0.57), with a slightly higher value in the snow-free road scenario with the lane detector (CL = 0.59) and slightly lower in the snow-free road without the lane detector (CL = 0.55). These values fall within the middle range of the cognitive load scale reported in the study by Wei et al. [

108], which allows us to interpret them as close to the so-called Goldilocks zone. In this range, the mental resources invested are sufficient for participants to be attentive and engaged in the tasks, but without overloading them to the point of degrading their performance.

Although participants appear to have remained in a state of optimal effort, the results on lane maintenance suggest that contextual factors, such as the presence of snow or the use of the lane detector, affect their behavior and determine where they focus their attention. Being within the Goldilocks zone does not in itself guarantee optimal performance in this case, as the environmental features and available technological aids also have an influence.

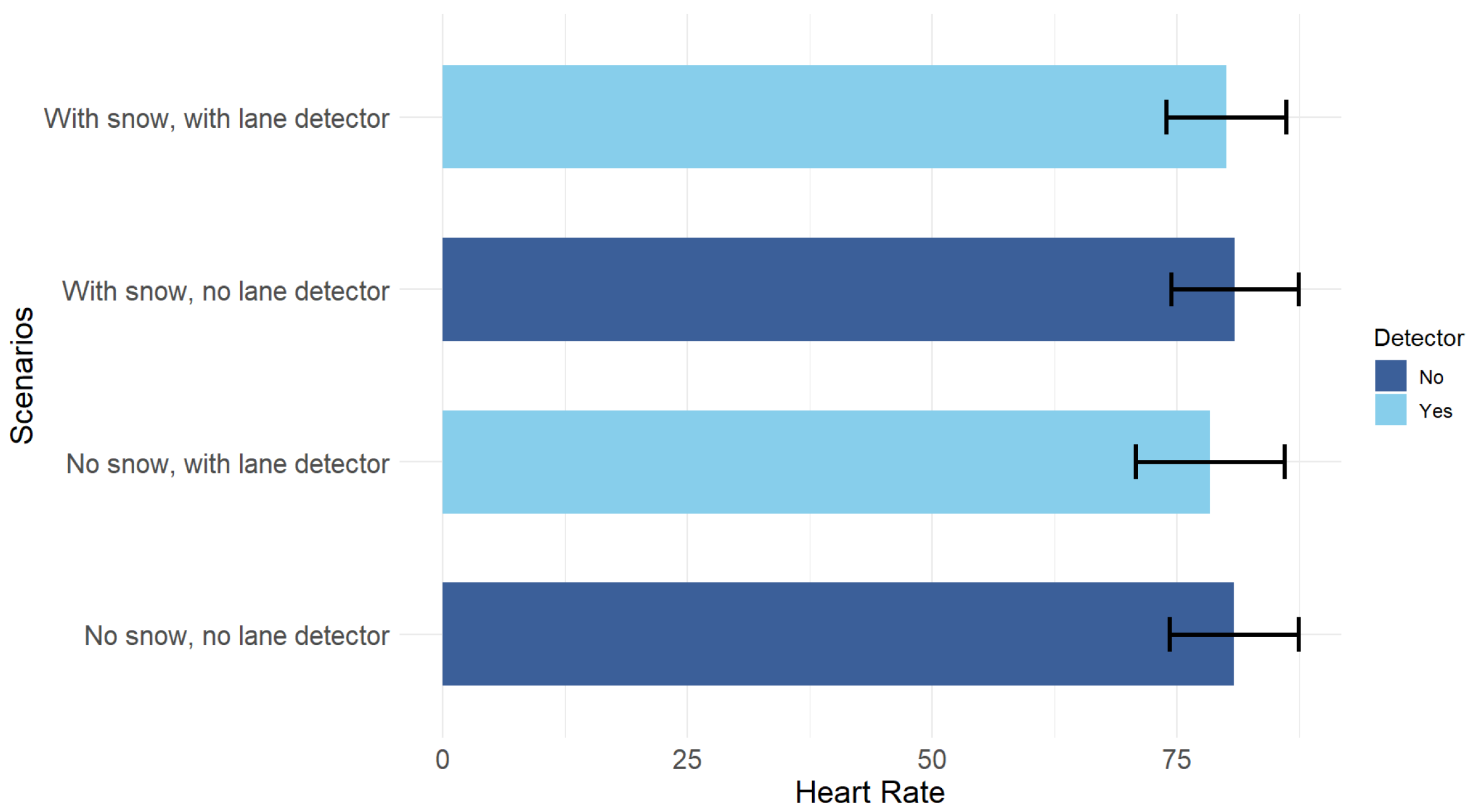

5.2.2. Heart Rate

Like cognitive load, the univariate ANOVA for heart rate also showed no statistically significant differences between the four situations (F(3,48) = 0.15,

p = 0.93), with the measurements being almost equal considering the variability of the data, as illustrated in

Figure 18.

The

repeated-measures ANOVA also revealed that the detector (F(1,48) = 0.29,

p = 0.59) or the absence or presence of snow (F(1,48) = 0.08,

p = 0.78) did not have significant main effects on heart rate. The interaction between the two factors was also not significant (F(1,48) = 0.07,

p = 0.79).

Figure 19 shows the snow × detector interaction graph for heart rate, suggesting that the experimental manipulation had no impact on this variable.

5.2.3. Physiological Measures Discussion

Despite our expectations, heart rate and cognitive load did not show statistically significant differences across driving scenarios, including conditions with and without the lane detection system. Several factors may explain these non-significant results:

Task demands: Although driving on snowy roads can be challenging, the controlled VR simulation lacked additional environmental complexity (e.g., dynamic traffic, pedestrians), which may have made the driving tasks insufficiently demanding to induce detectable changes in physiological measures.

Moderate cognitive load: Participants appeared to remain within a moderate range of cognitive load (the so-called Goldilocks zone), where mental resources were sufficient to stay attentive and engaged without overloading, potentially limiting detectable changes in physiological measures.

Technical and practical limitations associated with VR hardware: The HP Reverb G2 Omnicept Edition headset was used to record heart rate and cognitive load; however, sensor readings and stability can be influenced by factors such as facial sweat, cosmetic products, or improper sensor contact. During testing, the photoplethysmogram sensor occasionally failed to register data, and some participants sweated due to long (30 min) VR sessions. These factors could have reduced the sensitivity of the physiological metrics.

Adaptive strategies: From a human factors perspective, participants may have employed adaptive strategies to maintain stable performance, effectively compensating for environmental challenges, which could have stabilized physiological responses even under more complex scenarios.

Sample size: The small number of participants may have limited statistical power to detect subtle effects.

VR context: The VR context itself may influence physiological responses differently from real-world driving. Although driving on snowy roads is demanding in real life, our simulation provided a simplified and controlled setting, lacking dynamic traffic, pedestrians, and other real-world stressors. This reduction in complexity may have lowered cognitive load and physiological stress compared to actual driving conditions.

Overall, these results suggest that while participants’ performance showed measurable differences, heart rate and cognitive load may either reflect a genuine lack of strong effects under experimental conditions or the limited sensitivity of the measurements in prolonged VR driving simulations. Caution is warranted when interpreting these metrics in similar studies. Future research could improve sensor reliability and consider alternative or additional physiological measures to more accurately assess cognitive load and heart rate in VR driving experiments.

5.3. Lane Detection System

Acceptance of the Lane Detection System

To evaluate users’ adoption of the lane recognition system and identify the factors that most influence their decision to use the ADAS, we adapted the Technology Acceptance Model questionnaire to our experiment and administered it to participants [

56,

57,

96,

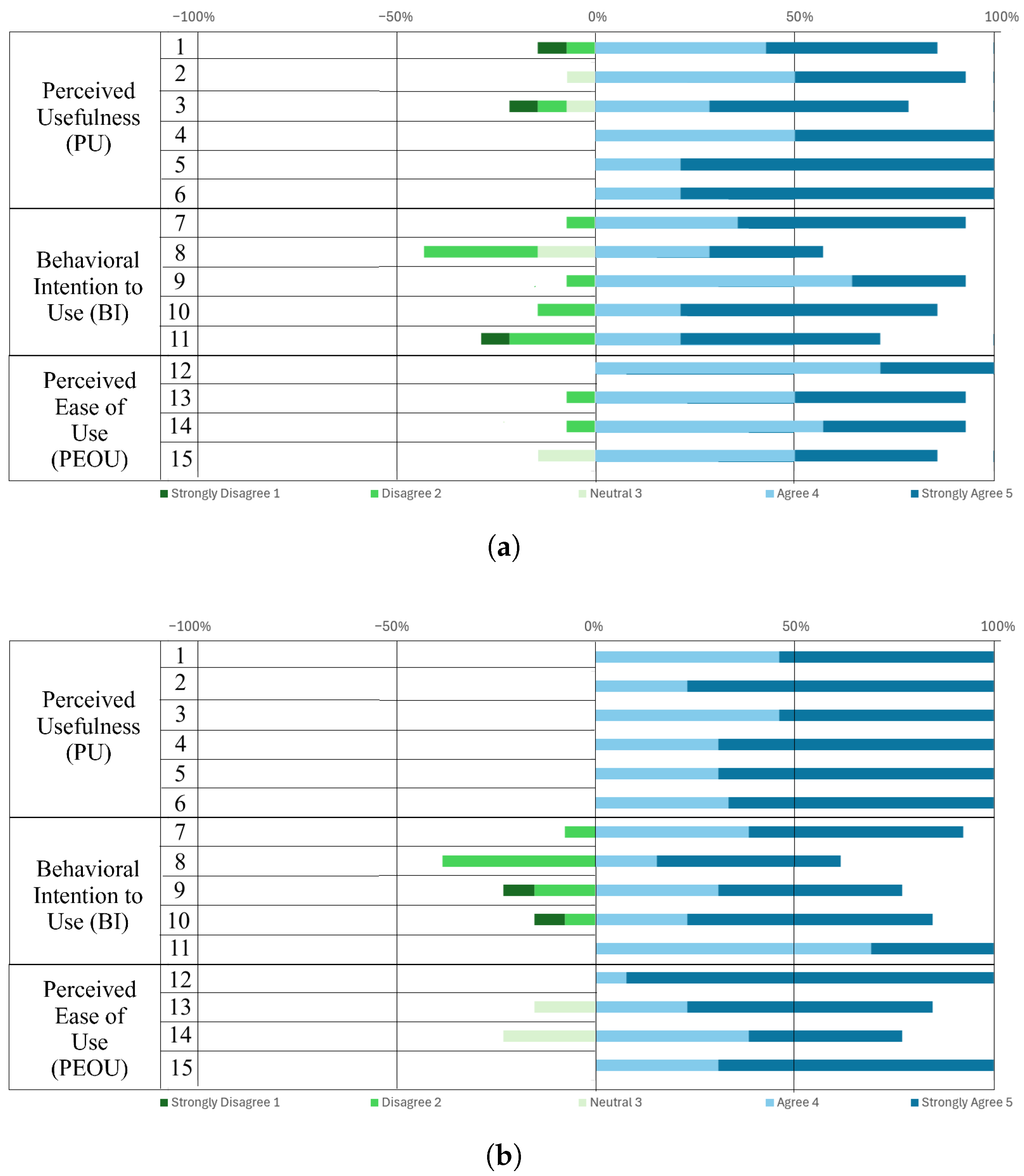

97]. This questionnaire uses a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from extremely likely to extremely unlikely, and classifies the questions into three constructs: perceived usefulness (PU), behavioral intention to use (BI), and perceived ease of use (PEOU).

Table 3 presents the questionnaire applied.

The questionnaire was administered twice: at the beginning of the test to understand participants’ initial concept of lane detectors, and at the end of the experiment to assess whether participants’ adoption of lane detectors changed when using our simulator.

We calculated the item correlations by construct using Cronbach’s

,

Table 4, to assess the validity of the collected data.

The Cronbach’s results from the pre-test confirm that the data are valid for re-evaluation. When comparing the pre-test with the post-test values, PU improved while BI remained at a similar value. In the case of PEOU, the change was drastic, with a decrease in . This result does not reflect a lack of validity or poor item design, since was high in the pre-test, but rather indicates a problem of response variability (ceiling effect) and redundancy between items.

In the post-test, participants perceived the system as easy to use, assigning scores of mainly 4 or 5 to all items, with means above 4.1 and low standard deviations (average SD = 0.29), as shown in

Figure 20b. In particular, very low variability was observed in the first and last PEOU items. This homogeneity reduces the variance and, therefore, the correlations between items. In contrast, the pre-test showed a greater dispersion in responses (

Figure 20a).

In analyzing the medians of the constructs together, the results after using the lane recognition system were very similar to those obtained before using it (

Table 5). This suggests that the driving experience with the lane detector in the virtual environment did not produce significant changes in participants’ intention to use the detector, their perception of its usefulness, or its perceived ease of use. In the statistical analysis using Wilcoxon tests, PU showed practically identical values in the pre-test (Mdn = 4.67) and post-test (Mdn = 4.67) (V = 30.5,

p = 0.3734, r = −0.196). BI decreased slightly after interaction with the system (Mdn = 4.2) compared to the initial measurement (Mdn = 4.4) (V = 25,

p = 0.8121, r = 0.0102). Finally, after using the detector, PEOU was higher (Mdn = 4.5) than the initial measurement (Mdn = 4.25) (V = 40,

p-value = 0.2146, r = −0.286); however, this difference did not reach statistical significance either.

When evaluating only the post-test acceptance results, participants reported on average a positive perception of usefulness, ease of use, and intention to use. In general, PU and PEOU showed high values with low variability, while BI was more dispersed and slightly lower. Correlation analyses between constructs revealed a moderate positive association between PEOU and BI (r = 0.42), while PU was not significantly related to BI (r = −0.07). These findings suggest that, in this context, perceived ease of use may have had a stronger influence than perceived usefulness on participants’ intention to use the system.

5.4. User Experience

To assess participants’ overall impression of their experience when interacting with the virtual vehicle and using the lane detector, we administered the short version of the user experience questionnaire (UEQ) [

109]. The questionnaire consists of pairs of opposite attributes that the system may have, with gradations between the opposites represented by seven circles. It measures classical aspects of usability through four scales—attractiveness, efficiency, perspicuity, and dependability—of which the latter three are pragmatic quality aspects (goal-directed). It also measures user experience through two scales—novelty and stimulation—which represent hedonic quality aspects (not goal-directed). The short version of the questionnaire includes the pragmatic quality and hedonic quality scales, as well as a global scale [

99]. Items are scored from −3 to +3, where values below −0.8 represent a negative evaluation, between −0.8 and 0.8 a neutral evaluation, and above 0.8 a positive evaluation [

100].

By calculating the mean scores of the pragmatic and hedonic quality aspects, we observed that the user experience with the lane detector was rated extremely positively, with scores greater than 0.8 for each item. Pragmatic quality received the highest score (2.1), although hedonic quality was not far behind (1.9). Overall, the user experience was rated as excellent according to UEQ standards, with the highest scores on the perspicuity, novelty, and efficiency scales, followed by stimulation and dependability. The system and driving experience were particularly highlighted by participants as clear, interesting, easy, leading-edge, and effective. Although items such as supportive and exciting did not receive the highest scores, participants still assigned them high values, as shown in

Table 6.

To obtain a clearer picture of the relative quality of the lane detector, we compared the user experience with this system to the driving experience without it. A paired-samples

t-test was conducted with a significance level of

= 0.05, revealing that, overall, the mean scores differed statistically significantly (overall

p-value: 0.023) and with practical relevance, showing a moderate-to-large effect size (Cohen’s d: 0.72). Both pragmatic quality (

p-value: 0.047, Cohen’s d: 0.62) and hedonic quality (

p-value: 0.018, Cohen’s d: 0.76) also differed significantly between the two experiences.

Figure 21 illustrates this difference.

Regarding the user experience questionnaire results without the detection system, overall scores were lower, indicating a neutral evaluation, with values of 0.5 for hedonic quality and 1.07 for pragmatic quality. Perspicuity and efficiency were again the highest-scoring scales, although they received lower values than in the experience with the detector, closely followed by stimulation. The novelty scale showed the lowest performance, as expected. Participants perceived driving without the detector as somewhat obstructive and boring, although easy, as shown in

Table 6.

5.5. Confidence in Lane Detection

To assess users’ trust in the lane detection system, we used the Situational Trust Scale for Automated Driving (STS-AD). This questionnaire evaluates different aspects of situational trust in the context of autonomous driving, taking into account six elements: trust, reaction, non-driving-related tasks (NDRTs), performance, risk, and judgment. The latter three items are scored inversely. For our experiment, we removed the NDRT element and defined the situations as driving on a snowy road and driving on a clear road. A 5-point Likert scale was used for the evaluation, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).

To assess the reliability of the adapted STS-AD version, we calculated Cronbach’s as an indicator of internal consistency, obtaining a value of = 0.81. This result reflects a good level of reliability, indicating that the items are adequately correlated and can be considered representative of a single construct of situational trust.

We calculated the average response to each item to assess situational trust. Overall, participants reported high situational trust in the lane detection system (3.9/5), perceiving it as reliable, safe, and competent. Positive ratings were observed for system judgment, appropriate reactions, and participant trust in both snowy and clear conditions, as shown in

Table 7. This table indicates which value is considered favorable and unfavorable for each item. Performance, risk, and judgment items were reverse-scored (1 = favorable, 5 = unfavorable). Despite the inherent risk of snowy driving, the use of the ADAS led participants to perceive the scenario as neutral in terms of risk, while the non-snowy scenario was rated as non-risky. The system was rated as outperforming the user in snowy conditions, whereas performance was considered similar on the clear road.

5.6. Feedback Evaluation

We asked participants about the lane information feedback provided by the detection system. Overall, they agreed that it was adequate, with an average rating of 4.15 (SD = 1.14) on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Regarding feedback channels, 50% of participants reported preferring a combination of visual and auditory feedback. A further 41.67% preferred visual feedback only, and 8.33% opted solely for auditory feedback, as they found visual feedback distracting. Concerning visual feedback, some participants suggested improvements through additional user support elements, such as a color code (green and red) to indicate lane deviation, directional markers to signal whether to move right or left to stay in the lane, or racing lines indicating the recommended speed for taking a curve without leaving the lane, which change color according to braking distance. Others suggested incorporating haptic feedback, so that the steering wheel vibrates slightly when the driver deviates from the lane.

Regarding the user interfaces evaluated, the HUD was the preferred option (69.2%), followed by the HDD located behind the steering wheel (23.1%) and finally the central HDD (7.7%). The HUD was rated as the most intuitive, easy to use, and dynamic, as it allowed participants to view the lane markings at all times without taking their eyes off the road. One participant additionally pointed out that its design appeared futuristic and suggested that the driver’s position should be considered when adjusting lane overlays to ensure accurate feedback.

In contrast, the central HDD was the least preferred by participants, as it forced them to take their eyes and attention off the road, causing insecurity and distraction, with potential risk in critical situations. The HDD located behind the steering wheel was perceived as less risky and distracting than the central HDD, although it still required glancing away from the road. Some participants also noted that the steering wheel partially obstructed the screen, making it difficult to view. Despite this, three users considered it appropriate and useful, highlighting that they found it an interesting design option.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

In this study, we presented the design of a virtual driving environment for the safe and controlled evaluation of vision-based lane detection algorithms in winter driving conditions, from a human-in-the-loop perspective. We integrate and validate a vision- and deep learning-based approach previously implemented to improve winter lane detection, and we monitored both quantitative and qualitative variables to examine the influence of contextual factors, such as snow presence or activation of the lane detection system, on user experience, lane-keeping performance, and user trust and acceptance of this type of ADAS.

The results suggest that activating the lane detector has a significant effect on user performance, reducing unintended lane departures. This finding highlights the system’s relevance, particularly under adverse weather conditions such as snow, where it compensates for performance deterioration due to low road visibility. Thus, the lane detector is supported as a resource that enhances both vehicle control and road safety.

Although physiological measurements did not show significant differences between scenarios, they provided valuable information on participants’ concentration, attention, readiness, stress, and relaxation levels. This underlines the importance of including both direct performance measures and psychophysiological indicators to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the effects of technological aids, task demands, and the environment. In addition, the ability to interact directly with this ADAS within the immersive environment contributed to increased user trust in the system and improved their driving experience on snowy roads, evidencing a highly positive user experience given the clarity, simplicity, effectiveness, and leading-edge nature of the detector under such conditions.

Future Work

We acknowledge that real-world driving involves additional variables not fully reproduced in our VR simulation. Future work will extend the VR environment to include more realistic conditions, such as dynamic traffic, irregular snow accumulation, multiple pedestrians, and additional weather variations. The lane detection algorithm, already integrated into the simulation, will be fully activated in real time using optimized or hardware-accelerated implementations. These enhancements aim to increase ecological validity, preserve user immersion, and allow a more comprehensive assessment of human–ADAS interaction under complex real-world winter driving conditions. Additional directions include integrating and testing additional user support elements, such as guidance lines and dynamic visual or auditory signals, with personalization mechanisms to optimize safety and user experience.

Driver responses will be assessed using multidimensional psychophysiological indicators, including EEG, skin conductance, and eye tracking, enabling a more comprehensive evaluation of drivers’ psychological and physical states and providing a richer, more reliable understanding of their behavior. To improve robustness and generalizability, future studies will involve larger and more gender-balanced participant samples.

Finally, we aim to investigate the path toward real-world deployment of the winter lane detection system, addressing hardware requirements, latency constraints, and performance under mixed or partially snowy conditions. Building on these insights, VR-based evaluations will be complemented with pilot testing in controlled real-road winter scenarios or augmented reality-based simulations, bridging the gap between virtual simulation and real-world evaluation, and ensuring that results from the immersive environment translate effectively to practical driving conditions. Direct quantitative comparisons of our method’s performance with commercial lane-keeping assistance systems are also planned, once resources, safety protocols, and ethical approvals are in place. This will strengthen the validity and contextual relevance of this study.