LMCSleepNet: A Lightweight Multi-Channel Sleep Staging Model Based on Wavelet Transform and Muli-Scale Convolutions

Abstract

1. Introduction

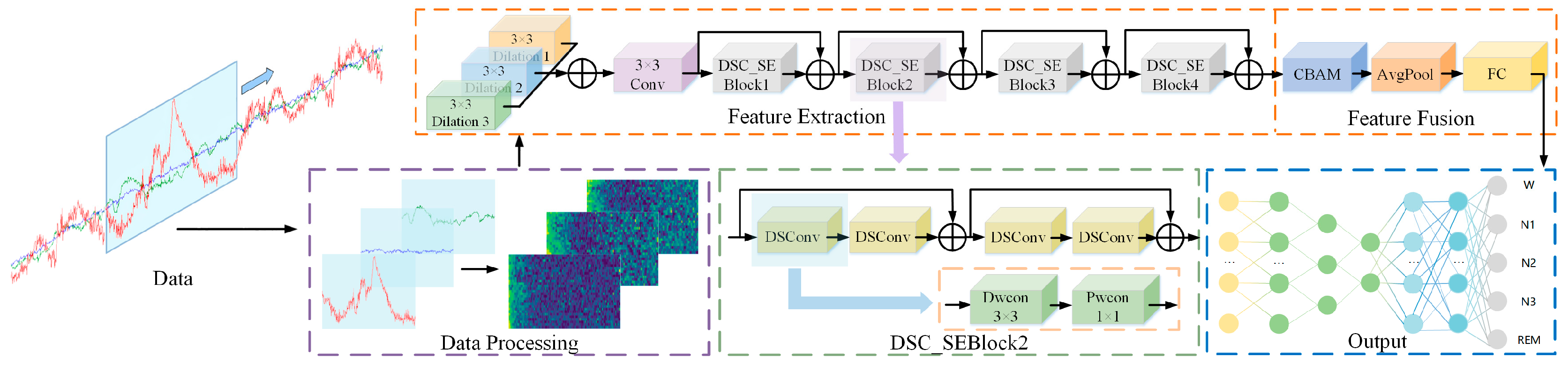

2. Design Based on LMCSleepNet Model

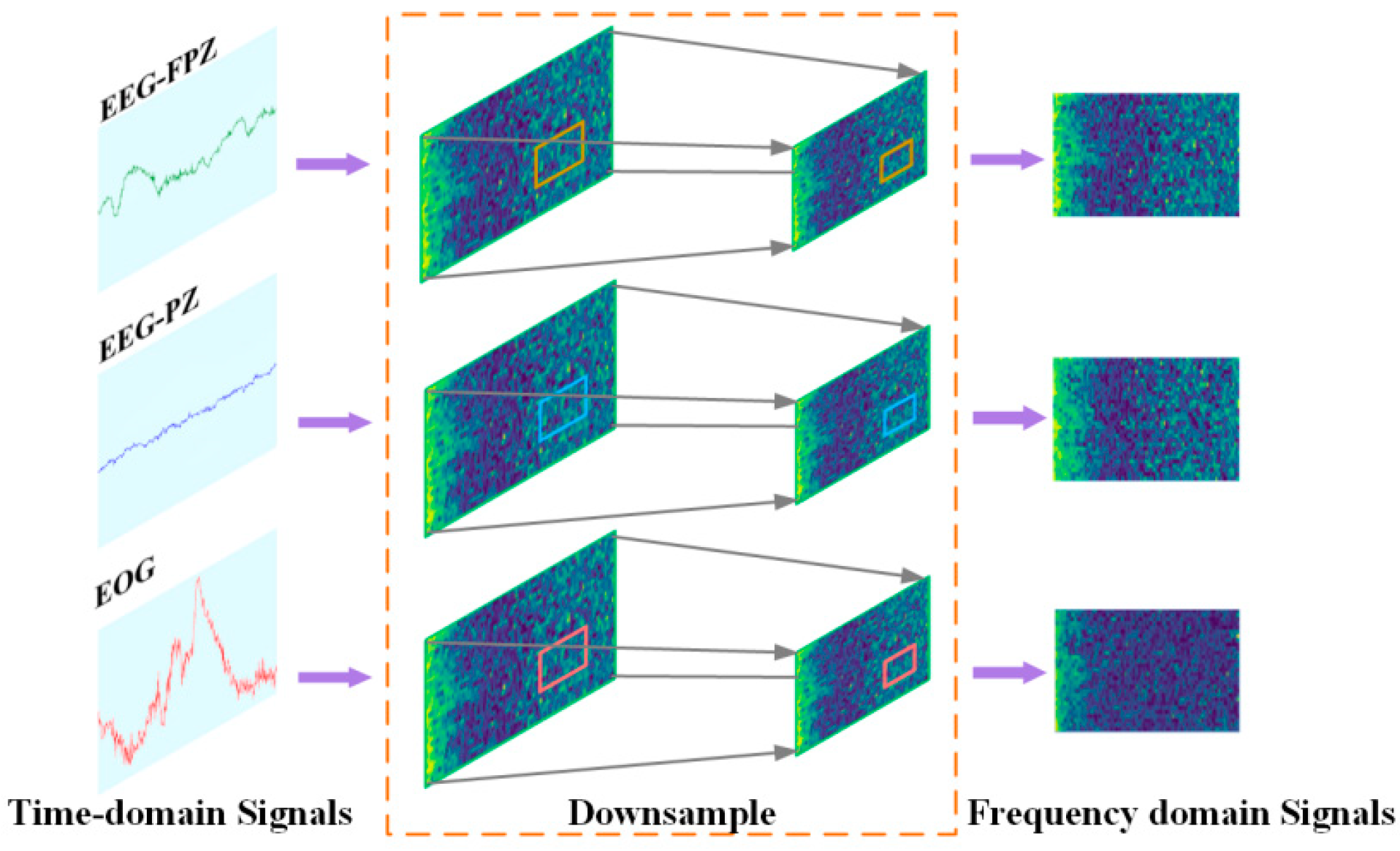

2.1. Data Preprocessing Module

2.2. Feature Extraction Module

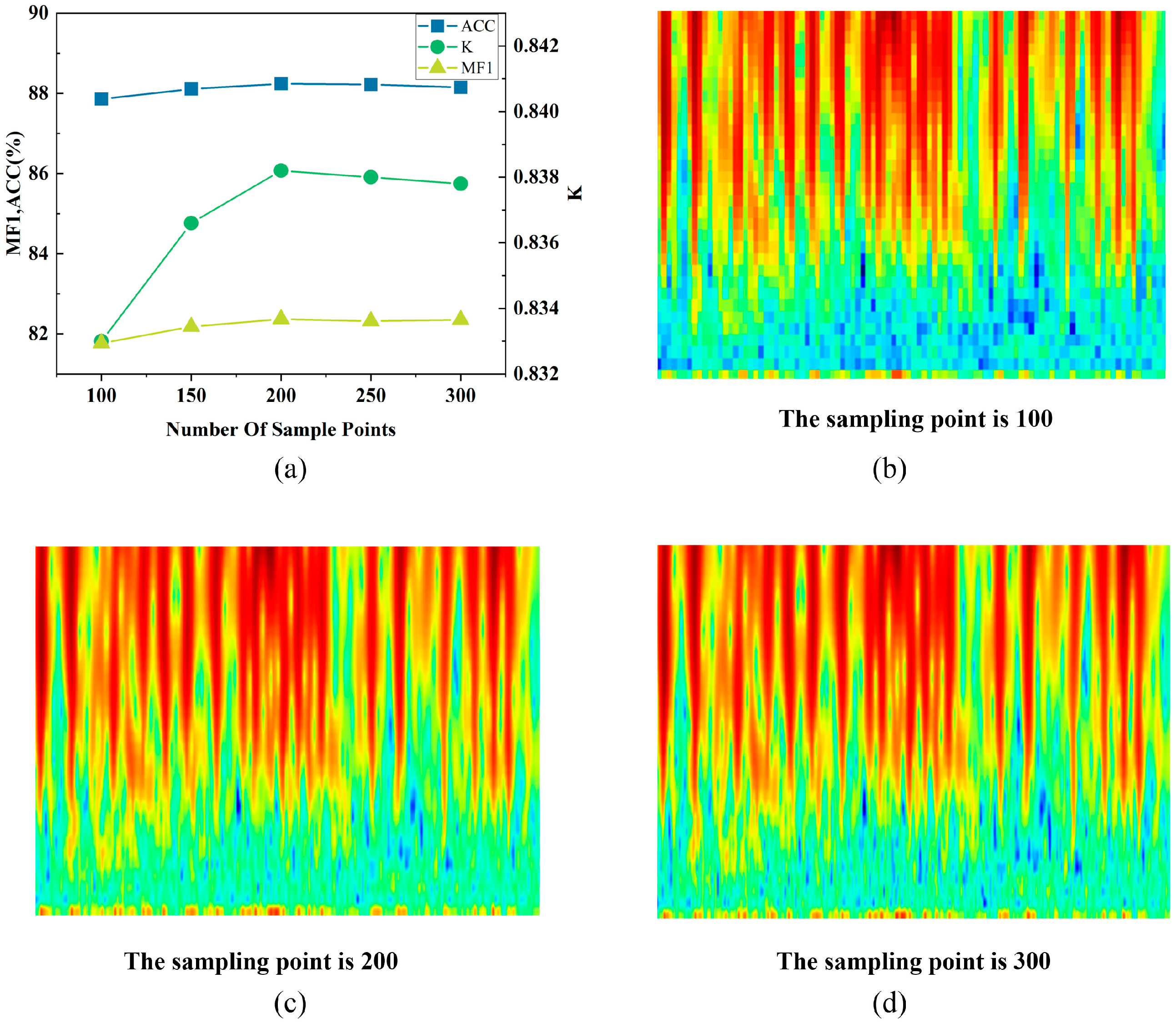

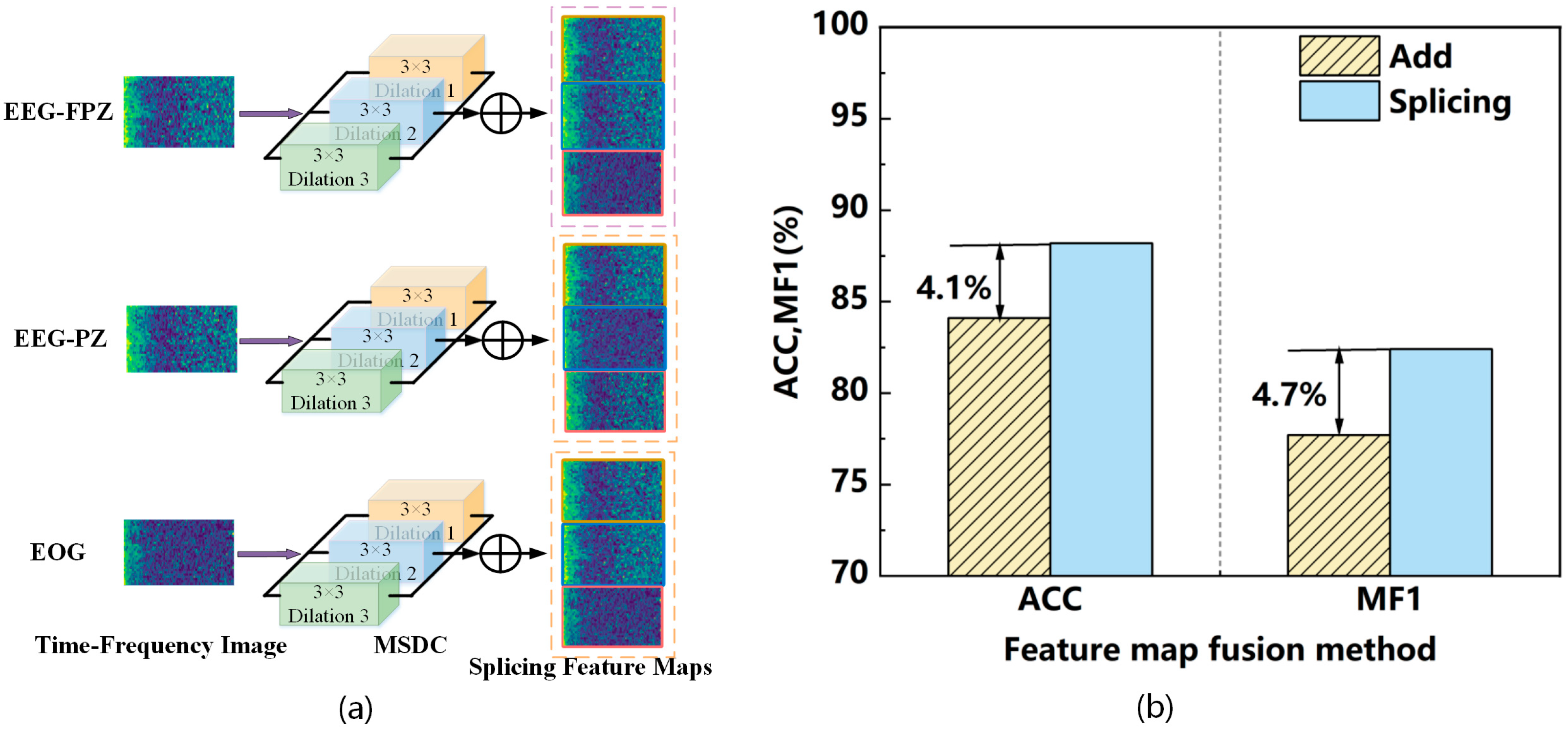

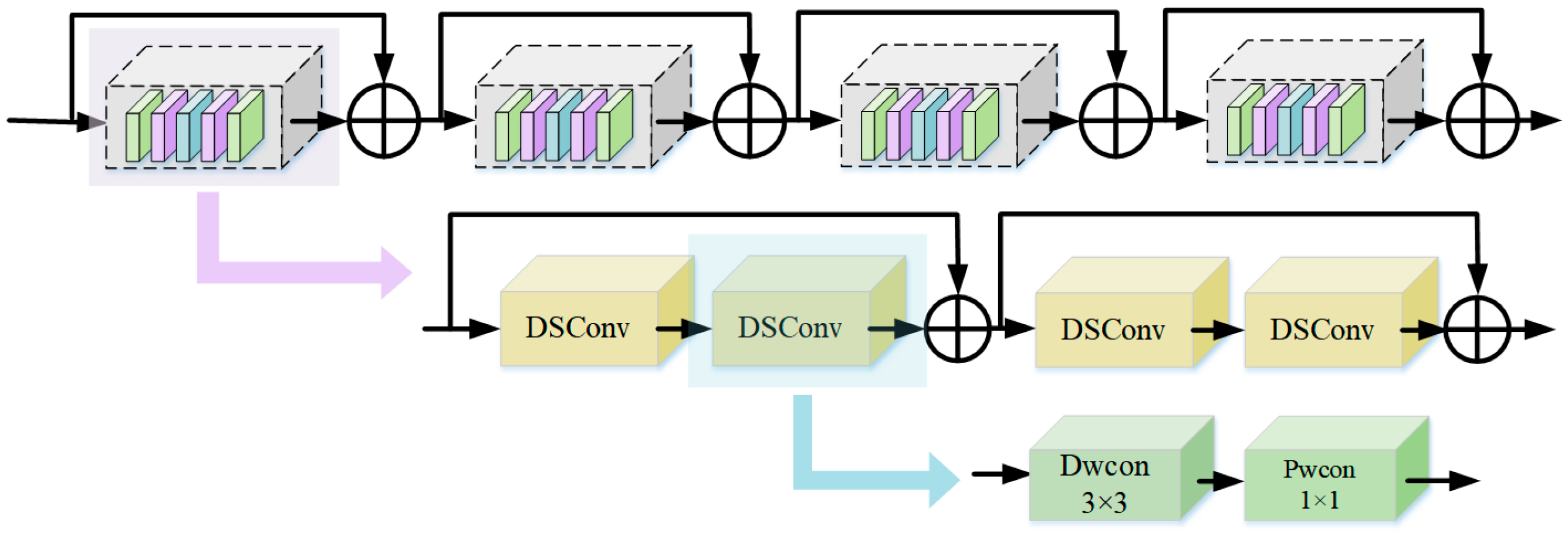

2.2.1. Mult-Scale Dilated Convolution Module

2.2.2. ResNet18 Module Based on Depth Separability

2.3. Feature Fusion Module

2.4. Classification Module

2.5. Efficiency Analysis of Modules

3. Experiment and Result Analysis

3.1. Dataset

3.2. Experimental Setup and Model Parameters

3.3. Evaluation Criteria

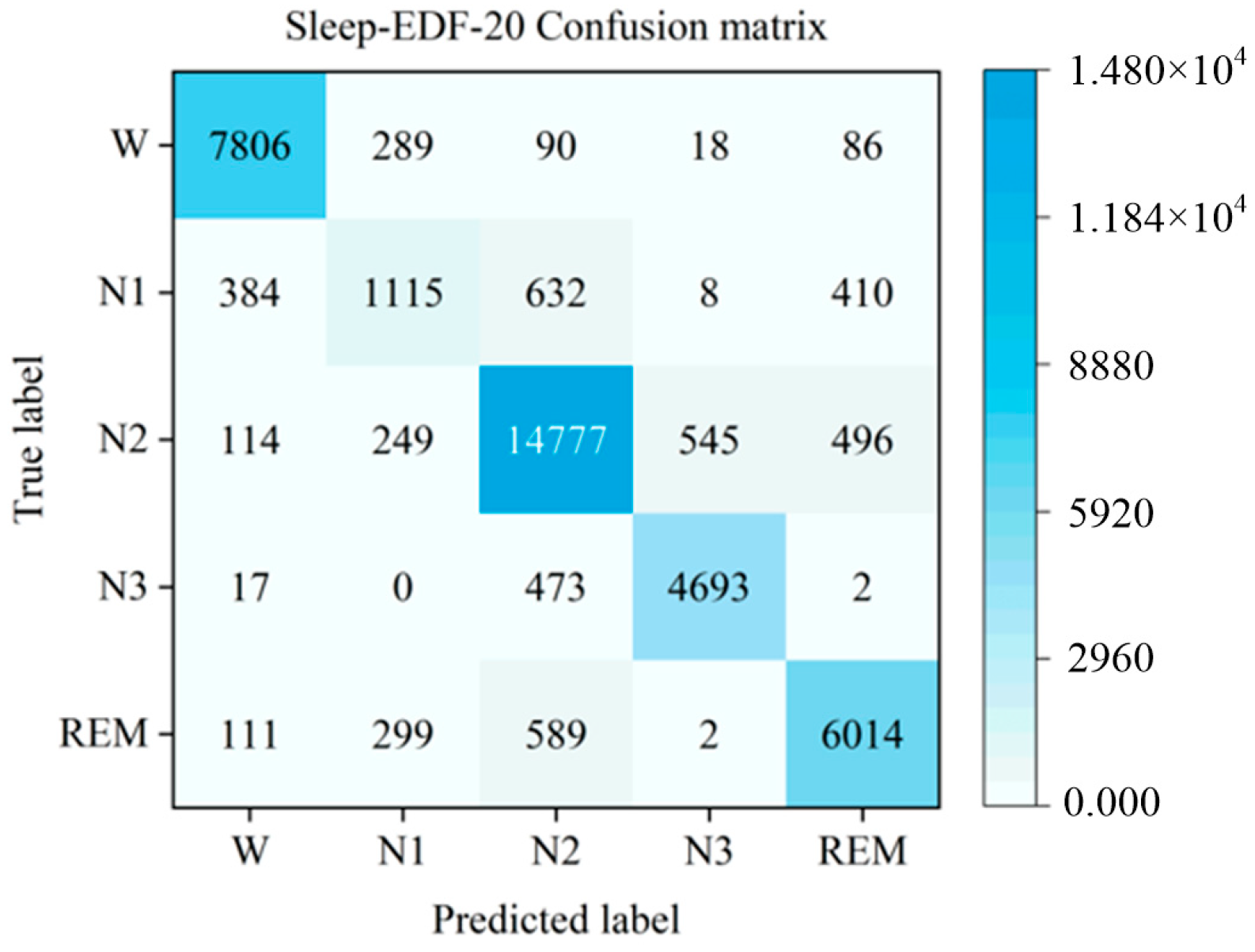

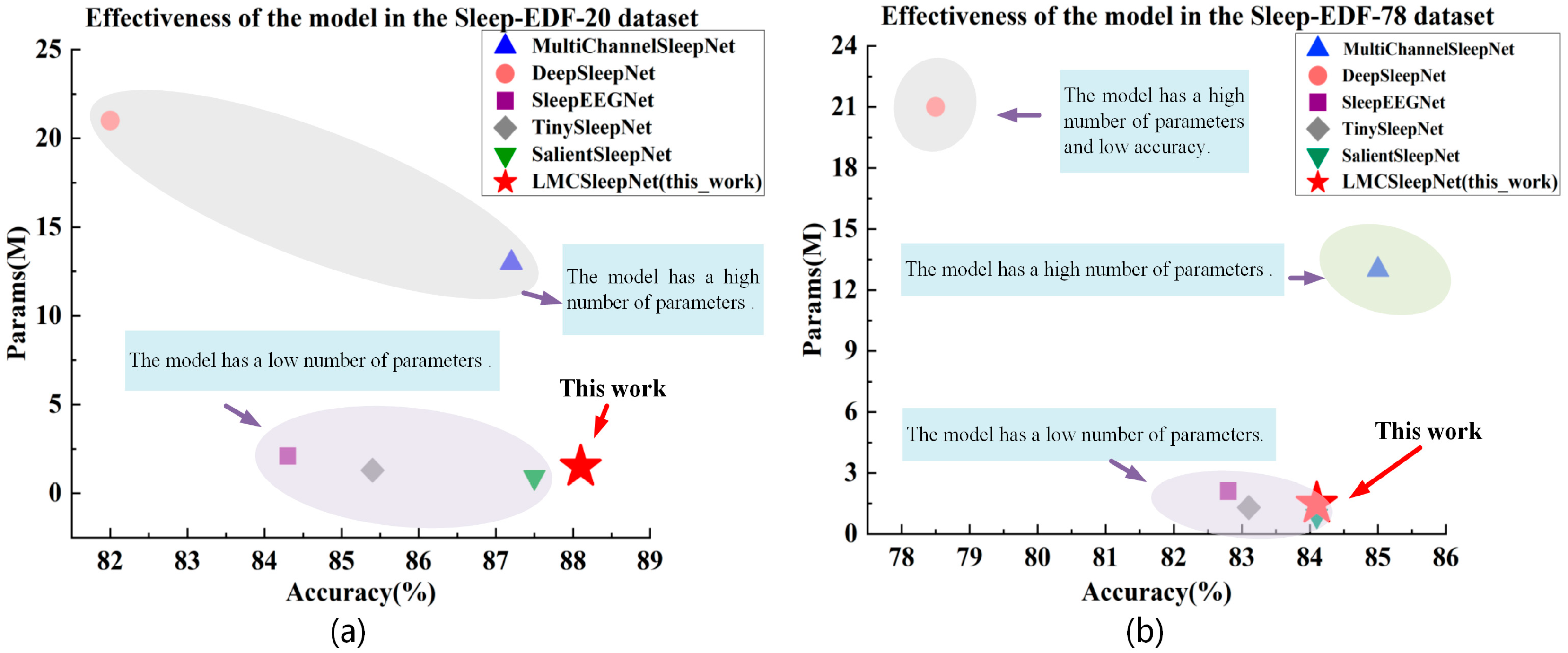

3.4. Comparison and Analysis of Experimental Results

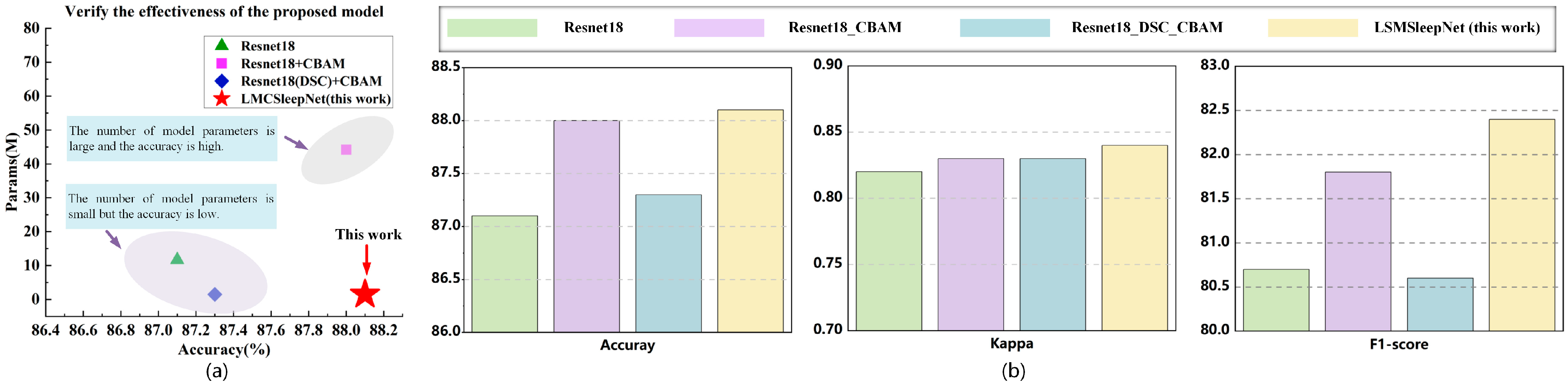

3.5. Ablation Experiment

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Faust, O.; Acharya, U.R.; Ng, E.Y.K.; Fujita, H. A Review of ECG—Based Diagnosis Support Systems for Obstructive Sleep Apnea. J. Mech. Med. Biol. 2016, 16, 1640004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassin, A.; Al-Mistarehi, A.-H.; Yonis, O.B.; Aleshawi, A.J.; Momany, S.M.; Khassawneh, B.Y. Prevalence of Sleep Disorders Among Medical Students and Their Association with Poor Academic Performance: A Cross-Sectional Study. Ann. Med. Surg. 2020, 58, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkalainen, H.; Aakko, J.; Nikkonen, S.; Kainulainen, S.; Leino, A.; Duce, B.; Afara, I.O.; Myllymaa, S.; Töyräs, J.; Leppänen, T. Accurate Deep Learning-Based Sleep Staging in a Clinical Population With Suspected Obstructive Sleep Apnea. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2020, 24, 2073–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.F.; Liu, X.X.; Hu, W.N.; Han, X.C.; Zhou, W.H.; Lu, A.D.; Wang, X.Z.; Wu, S.L. Night Sleep Duration and Risk of Cognitive Impairment in a Chinese Population: A Cross-Sectional Study. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2017, 30, 749–757. [Google Scholar]

- Rudoy, J.D.; Voss, J.L.; Westerberg, C.E.; Paller, K.A. Strengthening Individual Memories by Reactivating Them During Sleep. Science 2009, 326, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peter-Derex, L.; Yammine, P.; Bastuji, H.; Croisile, B. Sleep and Alzheimer’s Disease. Sleep Med. Rev. 2015, 19, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNicholas, W.T. Comorbid Obstructive Sleep Apnoea and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, S4253–S4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, P.C.; Richards, G. Recognition and Treatment of Sleep-Disordered Breathing: An Important Component of Chronic Disease Management. J. Transl. Med. 2017, 15, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danker-Hopfe, H.; Anderer, P.; Zeitlhofer, J.; Boeck, M.; Dorn, H.; Gruber, G.; Dorffner, G. Interrater Reliability for Sleep Scoring According to the Rechtschaffen & Kales and the New AASM Standard. J. Sleep Res. 2009, 18, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loh, H.W.; Ooi, C.P.; Vicnesh, J.; Oh, S.L.; Faust, O.; Gertych, A.; Acharya, U.R. Automated Detection of Sleep Stages Using Deep Learning Techniques: A Systematic Review of the Last Decade (2010–2020). Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koley, B.; Dey, D. An Ensemble System for Automatic Sleep Stage Classification Using Single Channel EEG Signal. Comput. Biol. Med. 2012, 42, 1186–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraiwan, L.; Lweesy, K.; Khasawneh, N.; Wenz, H.; Dickhaus, H. Automated Sleep Stage Identification System Based on Time–Frequency Analysis of a Single EEG Channel and Random Forest Classifier. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2012, 108, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güneş, S.; Polat, K.; Yosunkaya, Ş. Efficient Sleep Stage Recognition System Based on EEG Signal Using k-means Clustering Based Feature Weighting. Expert Syst. Appl. 2010, 37, 7922–7928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Supratak, A.; Pan, W.; Wu, C.; Matthews, P.M.; Guo, Y. Mixed Neural Network Approach for Temporal Sleep Stage Classification. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2017, 26, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sors, A.; Bonnet, S.; Mirek, S.; Vercueil, L.; Payen, J.F. A Convolutional Neural Network for Sleep Stage Scoring from Raw Single-Channel EEG. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2018, 42, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supratak, A.; Dong, H.; Wu, C.; Guo, Y. DeepSleepNet: A Model for Automatic Sleep Stage Scoring Based on Raw Single-Channel EEG. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2017, 25, 1998–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousavi, S.; Afghah, F.; Acharya, U.R. SleepEEGNet: Automated Sleep Stage Scoring with Sequence to Sequence Deep Learning Approach. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Li, X.; Liang, S.; Wang, L.; Duan, Q.; Yang, H.; Liao, X. MultichannelSleepNet: A Transformer-Based Model for Automatic Sleep Stage Classification with PSG. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2023, 27, 4204–4215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faust, O.; Razaghi, H.; Barika, R.; Ciaccio, E.J.; Acharya, U.R. A Review of Automated Sleep Stage Scoring Based on Physiological Signals for the New Millennia. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2019, 176, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Zhu, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H. A Single-Channel EEG Based Automatic Sleep Stage Classification Method Leveraging Deep One-Dimensional Convolutional Neural Network and Hidden Markov Model. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2021, 68, 102581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, L.; Li, L. MMASleepNet: A Multimodal Attention Network Based on Electrophysiological Signals for Automatic Sleep Staging. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 973761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.P.; Zaidi, S.; Mishra, A.; Yadav, V. Survey on Machine Learning in Speech Emotion Recognition and Vision Systems Using a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN). Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2022, 29, 1753–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siami-Namini, S.; Tavakoli, N.; Namin, A.S. The Performance of LSTM and BiLSTM in Forecasting Time Series. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 9–12 December 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 3285–3292. [Google Scholar]

- Han, K.; Xiao, A.; Wu, E.; Guo, J.; Xu, C.; Wang, Y. Transformer in Transformer. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 15908–15919. [Google Scholar]

- Wacker, M.; Witte, H. Time-Frequency Techniques in Biomedical Signal Analysis. Methods Inf. Med. 2013, 52, 279–296. [Google Scholar]

- Lawhern, V.J.; Solon, A.J.; Waytowich, N.R.; Gordon, S.M.; Hung, C.P.; Lance, B.J. EEGNet: A Compact Convolutional Neural Network for EEG-Based Brain–Computer Interfaces. J. Neural Eng. 2018, 15, 056013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. MobileNets: Efficient Convolutional Neural Networks for Mobile Vision Applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fu, X.; Qi, G.; Zhang, N. A Multi-Scale Feature Fusion Convolutional Neural Network for Facial Expression Recognition. Expert Syst. 2024, 41, e13517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Dong, F.; Wu, J.; Xu, Y. Downsampling of EEG Signals for Deep Learning-Based Epilepsy Detection. IEEE Sens. Lett. 2023, 7, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-Based Learning Applied to Document Recognition. Proc. IEEE 2002, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Ahuja, N.; Yang, R.; Tan, K.H.; Davis, J.; Culbertson, B.; Wang, G. Fusion of Median and Bilateral Filtering for Range Image Upsampling. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2013, 22, 4841–4852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S.; Shlens, J.; Wojna, Z. Rethinking the Inception Architecture for Computer Vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 2818–2826. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Z.; Chen, W.; Chen, Y. Multi-Scale Convolutional Neural Networks for Time Series Classification. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1603.06995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, B.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Tuk, B.; Kamphuisen, H.A.; Oberye, J.J. Analysis of a Sleep-Dependent Neuronal Feedback Loop: The Slow-Wave Microcontinuity of the EEG. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2000, 47, 1185–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberger, A.L.; Amaral, L.A.N.; Glass, L.; Hausdorff, J.M.; Ivanov, P.C.; Mark, R.G.; Mietus, J.E.; Moody, G.B.; Peng, C.-K.; Stanley, H.E. PhysioBank, PhysioToolkit, and PhysioNet: Components of a New Research Resource for Complex Physiologic Signals. Circulation 2000, 101, E215–E220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolovsky, M.; Guerrero, F.; Paisarnsrisomsuk, S.; Ruiz, C.; Alvarez, S.A. Deep Learning for Automated Feature Discovery and Classification of Sleep Stages. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2019, 17, 1835–1845. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, H.; Andreotti, F.; Cooray, N.; Chén, O.Y.; De Vos, M. Joint Classification and Prediction CNN Framework for Automatic Sleep Stage Classification. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 66, 1285–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Yan, R.; Mahini, R.; Wei, L.; Wang, Z.; Mathiak, K.; Cong, F. End-to-End Sleep Staging Using Convolutional Neural Network in Raw Single-Channel EEG. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2021, 63, 102203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Decoupled Weight Decay Regularization. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.05101. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, D.D.; Schapire, R.E.; Callan, J.P.; Papka, R. Training Algorithms for Linear Text Classifiers. In Proceedings of the 19th Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Zurich, Switzerland, 18–22 August 1996; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 298–306. [Google Scholar]

- Supratak, A.; Guo, Y. TinySleepNet: An Efficient Deep Learning Model for Sleep Stage Scoring Based on Raw Single-Channel EEG. In Proceedings of the 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 July 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 641–644. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Z.; Lin, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Xie, P.; Zhang, Y. SalientSleepNet: Multimodal Salient Wave Detection Network for Sleep Staging. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.13864. [Google Scholar]

| Stage (AASM) | SleepEDF-20 (Number/30 s) | Proportion/% | SleepEDF-78 (Number/30 s) | Proportion/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| W | 9118 | 21.10 | 66,822 | 34.00 |

| N1 | 2804 | 6.50 | 21,522 | 11.00 |

| N2 | 17,799 | 41.30 | 69,132 | 35.20 |

| N3 | 5703 | 13.20 | 13,039 | 6.60 |

| REM | 7717 | 17.90 | 25,835 | 13.20 |

| Total | 43,141 | 100% | 196,350 | 100 |

| Layer | Kernel Size/ Channels, Stride | Output Size |

|---|---|---|

| Input | ||

| MSDC | ||

| MaxPool | ||

| Layer 1 (DSC) | ||

| Layer 2 (DSC) | ||

| Layer 3 (DSC) | ||

| Layer 4 (DSC) | ||

| Channel Attention (CA) | ||

| Spatial Attention (SA) | ||

| Average Pooling |

| True Label | Predicted Label | Performance Metrics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W | N1 | N2 | N3 | REM | PR (%) | RE (%) | F1 (%) | |

| W | 7844 | 276 | 87 | 14 | 68 | 92.7 ± 0.2 | 94.6 ± 0.2 | 93.7 ± 0.2 |

| N1 | 387 | 1131 | 614 | 12 | 405 | 59.4 ± 0.3 | 44.4 ± 0.3 | 51.5 ± 0.3 |

| N2 | 109 | 241 | 14,858 | 514 | 459 | 89.5 ± 0.3 | 91.8 ± 0.3 | 90.6 ± 0.4 |

| N3 | 17 | 0 | 461 | 4706 | 1 | 89.7 ± 0.2 | 90.8 ± 0.4 | 90.2 ± 0.2 |

| REM | 106 | 257 | 582 | 2 | 6068 | 86.7 ± 0.2 | 86.5 ± 0.2 | 86.6 ± 0.3 |

| Model | Channel | Overall Metrics | Per-Class F1-Score | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acc | k | MFI | Params/M | W | N1 | N2 | N3 | REM | ||

| DeepSleepNet | EEG | 82.0 ± 0.2 | 0.76 ± 0.05 | 76.9 ± 0.6 | 21.0 | 85.0 | 47.0 | 86.0 | 85.0 | 82.0 |

| MultiChannelSleepNet | EEG-Fpz-Cz, EEG-Pz-Oz, EOG | 87.2 ± 0.3 | 0.82 ± 0.06 | 81.2 ± 0.5 | 13.0 | 92.8 | 49.1 | 90.0 | 89.3 | 84.8 |

| SleepEEGNet | EEG | 84.3 ± 0.2 | 0.79 ± 0.06 | 79.7 ± 0.6 | 2.1 | 89.2 | 52.2 | 89.8 | 85.1 | 85.0 |

| TinySleepNet | EEG | 85.4 ± 0.3 | - | 80.5 ± 0.5 | 1.3 | 90.1 | 51.4 | 88.5 | 88.3 | 84.3 |

| SalientSleepNet | EEG-Fpz-Cz, EEG-Pz-Oz, EOG | 87.5 ± 0.3 | - | 83.0 ± 0.6 | 0.9 | 92.3 | 56.2 | 89.9 | 87.2 | 89.2 |

| LMCSleepNet (this work) | EEG-Fpz-Cz, EEG-Pz-Oz, EOG | 88.2 ± 0.6 | 0.84 ± 0.6 | 82.4 ± 0.4 | 1.49 | 93.7 | 51.5 | 90.6 | 90.2 | 86.6 |

| Model | Channel | Overall Metrics | Per-Class F1-Score | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acc | k | MFI | Params/M | W | N1 | N2 | N3 | REM | ||

| DeepSleepNet | EEG | 78.5 | 0.73 | 75.3 | 21.0 | 91.0 | 47.0 | 81.0 | 69.0 | 79.0 |

| MultiChannelSleepNet | EEG-Fpz-Cz, EEG-Pz-Oz, EOG | 85.0 | 0.79 | 79.6 | 13.0 | 94.0 | 53.0 | 86.9 | 81.8 | 82.6 |

| SleepEEGNet | EEG | 82.8 | 0.73 | 77.0 | 2.1 | 90.3 | 44.6 | 85.7 | 81.6 | 82.9 |

| TinySleepNet | EEG | 83.1 | - | 78.1 | 1.3 | 92.8 | 51.0 | 85.3 | 81.1 | 80.3 |

| SalientSleepNet | EEG-Fpz-Cz, EEG-Pz-Oz, EOG | 84.1 | - | 79.5 | 0.9 | 93.3 | 54.2 | 85.8 | 78.3 | 85.8 |

| LMCSleepNet (this work) | EEG-Fpz-Cz, EEG-Pz-Oz, EOG | 84.1 | 0.77 | 77.7 | 1.49 | 94.2 | 48.5 | 85.8 | 77.6 | 82.7 |

| ResNet18 | CBAM | DSC | MSDC | Overall Metrics | Per-Class F1-Score | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acc | k | MFI | Params/M | W | N1 | N2 | N3 | REM | ||||

| √ | 87.1 | 0.82 | 80.7 | 11.69 | 93.2 | 47.4 | 89.8 | 88.6 | 84.6 | |||

| √ | √ | 88.0 | 0.83 | 81.8 | 11.71 | 93.6 | 49.0 | 90.5 | 89.7 | 86.1 | ||

| √ | √ | √ | 87.3 | 0.83 | 80.6 | 1.48 | 93.2 | 44.9 | 90.1 | 90.0 | 85.1 | |

| √ | √ | √ | √ | 88.2 | 0.84 | 82.4 | 1.49 | 93.7 | 51.5 | 90.6 | 90.2 | 86.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Yu, T.; Zhang, Y. LMCSleepNet: A Lightweight Multi-Channel Sleep Staging Model Based on Wavelet Transform and Muli-Scale Convolutions. Sensors 2025, 25, 6065. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25196065

Yang J, Chen Y, Yu T, Zhang Y. LMCSleepNet: A Lightweight Multi-Channel Sleep Staging Model Based on Wavelet Transform and Muli-Scale Convolutions. Sensors. 2025; 25(19):6065. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25196065

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Jiayi, Yuanyuan Chen, Tingting Yu, and Ying Zhang. 2025. "LMCSleepNet: A Lightweight Multi-Channel Sleep Staging Model Based on Wavelet Transform and Muli-Scale Convolutions" Sensors 25, no. 19: 6065. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25196065

APA StyleYang, J., Chen, Y., Yu, T., & Zhang, Y. (2025). LMCSleepNet: A Lightweight Multi-Channel Sleep Staging Model Based on Wavelet Transform and Muli-Scale Convolutions. Sensors, 25(19), 6065. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25196065