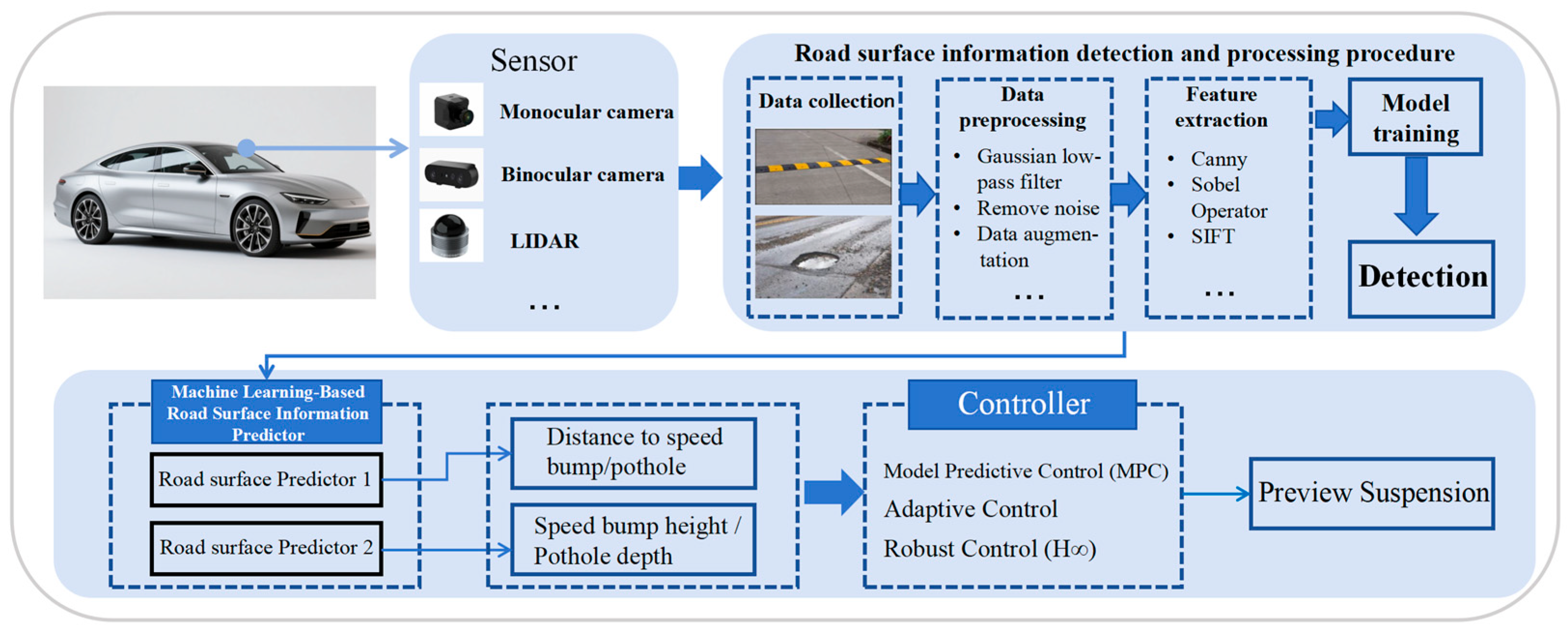

Review of Uneven Road Surface Information Perception Methods for Suspension Preview Control

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Collection of Road Surface Information Datasets

3. Method Classification

3.1. Road Surface Information Detection Based on Traditional Dynamics

3.2. Road Surface Information Detection Based on 2D Data

3.3. Road Surface Information Detection Based on 3D

3.4. Road Surface Information Detection Based on Deep/Machine Learning

3.5. Multi-Sensor Fusion Methods

3.6. Comparative Analysis and Challenges

4. Elevation Information Detection

5. Future Outlook

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2D | Two-dimensional |

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| FFT | Fast Fourier transform |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| ICV | Intelligent connected vehicle |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

| ToF | Time of flight |

| MLS | Mobile laser scanning |

| SIFT | Scale-invariant feature transform |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| FIS | Fuzzy inference system |

| AUC | Area under Curve |

| CWT | Continuous wavelet transform |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| EFDD | Extract data features filter |

| CNN-LSTM | Convolutional Neural Network- Long Short-Term Memory |

| ROI | Region of interest |

| FCM | Fuzzy c-means |

| GMM | Gaussian Mixture Model |

| MRF | Markov Random Field |

| RANSAC | Random Sample Consensus |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| SFCW | Stepped-frequency continuous wave |

| DSST | Discriminative scale space tracking |

| mAP | Mean Average Precision |

| FNR | False negative rate |

| TPR | True positive rate |

| HOG | Histogram of Oriented Gradients |

| NST | Negative sample training |

| SPP | Spatial pyramid pooling |

| FPN | Feature pyramid network |

| GPR | Ground-penetrating radar |

| GPS | Global positioning system |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| CoU | Complete-IoU |

| DIoU | Distance-IoU |

| SFM | Structure from motion |

| RPN | Region proposal network |

| DR | Damage rate |

| PCI | Pavement condition index |

| ADAS | Advanced driver assistance systems |

| NAS | Neural architecture search |

| KD | Knowledge distillation |

| 3F2N | Three-Filters-To-Normal |

| DBSCAN | Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise |

| cGAN | Conditional generative adversarial networks |

| GAL | Graph Attention Layer |

| AP | Average precision |

| DCN | Deep convolutional neural networks |

| ESRGAN | Enhanced Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Network |

| LR | Low-resolution |

| SR | super-resolution |

References

- Liu, J.; Luo, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Li, K.; Huang, H.; Xiong, H. A probabilistic architecture of long-term vehicle trajectory prediction for autonomous driving. Engineering 2022, 19, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukoševičius, V.; Makaras, R.; Rutka, A.; Keršys, R.; Dargužis, A.; Skvireckas, R. Investigation of vehicle stability with consideration of suspension performance. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dridi, I.; Hamza, A.; Ben Yahia, N. A new approach to controlling an active suspension system based on reinforcement learning. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2023, 15, 16878132231180480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Yu, Z.; Wu, P.; Hou, Z. Analytical solutions of the energy harvesting potential from vehicle vertical vibration based on statistical energy conservation. Energy 2023, 264, 126111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Wu, W.; Yuan, S. Longitudinal-vertical dynamics of wheeled vehicle under off-road conditions. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2022, 60, 470–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Bai, X.-X.F.; Zhu, A.-D.; Wu, D.; Deng, X.-C.; Li, Z.-D. Influence of balanced suspension on handling stability and ride comfort of off-road vehicle. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 2021, 235, 1602–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues Moreira Resende da Silva, R.; Lucas Reinaldo, I.; Pinheiro Montenegro, D.; Simão Rodrigues, G.; Dias Rossi Lopes, E. Optimization of vehicle suspension parameters based on ride comfort and stability requirements. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 2021, 235, 1920–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unnithan, A.R.R.; Subramaniam, S. Enhancing ride comfort and stability of a large van using an improved semi-active stability augmentation system. SAE Int. J. Veh. Dyn. Stab. NVH 2022, 6, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, M.; Samn, A. Passive vehicle suspension system optimization using Harris Hawk Optimization algorithm. Math. Comput. Simul. 2022, 191, 328–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Li, J.; Huang, R.; Yang, X.; Chen, J.; Chen, L.; Li, M. Vibration control of vehicle ISD suspension based on the fractional-order SH-GH stragety. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 234, 112880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, C.; Chen, L.; Zhang, X. Phase deviation of semi-active suspension control and its compensation with inertial suspension. Acta Mech. Sin. 2024, 40, 523367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Li, Z.; Tian, X.; Ji, K.; Yang, X. Vibration Suppression of the Vehicle Mechatronic ISD Suspension Using the Fractional-Order Biquadratic Electrical Network. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Xie, F.; Zhou, R.; Huang, X.; Cheng, W.; Tian, Z.; Li, Z. Vibration analysis and control of semi-active suspension system based on continuous damping control shock absorber. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2023, 45, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-J.; Huang, Z.-Q.; Liu, H.-J.; Qiu, G.-Q.; Gu, Y.-K. A unified stiffness model of rolling lobe air spring with nonlinear structural parameters and air pressure dependence of rubber bellows. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 2025, 239, 407–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Ge, X.; Han, Q.-L. Decentralized dynamic event-triggered communication and active suspension control of in-wheel motor driven electric vehicles with dynamic damping. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2021, 8, 971–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Li, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhang, N. Efficiency improvement of vehicle active suspension based on multi-objective integrated optimization. J. Vib. Control 2017, 23, 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Quan, W.; Dong, Z.; Dong, Y.; Si, C. Dynamic response analysis of vehicle and asphalt pavement coupled system with the excitation of road surface unevenness. Appl. Math. Model. 2022, 104, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lin, W. Predictor-based observer and controller for nonlinear systems with input/output delays. Syst. Control Lett. 2024, 184, 105723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongyang, T.; Daming, H.; Xingyi, H.; Aheto, J.H.; Yi, R.; Yu, W.; Ji, L.; Shuai, N.; Mengqi, X. Detection of browning of fresh-cut potato chips based on machine vision and electronic nose. J. Food Process Eng. 2021, 44, e13631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Chen, J.; Guan, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Shi, H.; Cheng, K. Development of a combined harvester navigation control system based on visual simultaneous localization and mapping-inertial guidance fusion. J. Agric. Eng. 2024, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deubel, C.; Ernst, S.; Prokop, G. Objective evaluation methods of vehicle ride comfort—A literature review. J. Sound Vib. 2023, 548, 117515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, Z.; Li, M.; Shang, Z. Dynamic Measurement Method for Steering Wheel Angle of Autonomous Agricultural Vehicles. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, S.; Hu, X.; Deng, P.; Li, B.; Li, Y.; Ai, Y.; Yang, D.; Li, L.; Xuanyuan, Z.; Zhu, F. Motion planning for autonomous driving: The state of the art and future perspectives. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 8, 3692–3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-M.; Toda, K.; Gui, X.; Seo, S.H.; Igarashi, T. Can eyes on a car reduce traffic accidents? In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Automotive User Interfaces and Interactive Vehicular Applications, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 17–20 September 2022; pp. 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, J. Jaguar Land Rover’s ‘Pothole Alert’ Warns About Hated Hazard. 2015. Available online: https://www.motorauthority.com/news/1098673_jaguar-land-rovers-pothole-alert-warns-about-hated-hazard (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Dhiman, A.; Klette, R. Pothole detection using computer vision and learning. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2019, 21, 3536–3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitrakis, M.; Alexandridis, A. Active vehicle suspension control using road preview model predictive control and radial basis function networks. Appl. Soft Comput. 2022, 120, 108646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.-Y.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Zhang, G.-Z. YOLOv5s-road: Road surface defect detection under engineering environments based on CNN-transformer and adaptively spatial feature fusion. Measurement 2025, 242, 115990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sime, M.; Bailey, G.; Hajj, E.; Chkaiban, R. Impact of pavement roughness on fuel consumption for a range of vehicle types. J. Transp. Eng. Part B Pavements 2021, 147, 04021022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirziyoyeva, Z.; Salahodjaev, R. Renewable energy and CO2 emissions intensity in the top carbon intense countries. Renew. Energy 2022, 192, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, C.; Zheng, G.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, H.; Li, M.; Zhang, L.; Tan, Y. A lightweight detection method of pavement potholes based on binocular stereo vision and deep learning. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 436, 136733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goenaga, B.; Underwood, S.; Fuentes, L. Effect of speed bumps on pavement condition. Transp. Res. Rec. 2020, 2674, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Nguyen, V.; Zhou, H. Research on semi-active air suspensions of heavy trucks based on a combination of machine learning and optimal fuzzy control. SAE Int. J. Veh. Dyn. Stab. NVH 2021, 5, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Zhang, W.; Xiao, Y.; Yao, L.; Fang, Z. Cooperative perception technology of autonomous driving in the internet of vehicles environment: A review. Sensors 2022, 22, 5535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Yan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, K.; Liu, R.; Lin, C. RDD-YOLOv5: Road defect detection algorithm with self-attention based on unmanned aerial vehicle inspection. Sensors 2023, 23, 8241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Li, S.; Peng, L.; Jiang, B.; Huang, R.; Chen, Y. Ultra-fast semantic map perception model for autonomous driving. Neurocomputing 2024, 599, 128162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tu, C.; Gao, K.; Wang, L. Multisensor information fusion: Future of environmental perception in intelligent vehicles. J. Intell. Connect. Veh. 2024, 7, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Xue, X.; Le, F.; Mao, H.; Ding, S. Design and experiment of electro hydraulic active suspension for controlling the rolling motion of spray boom. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2019, 12, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Xu, L.; Wang, J.; Li, Y. Inertial force balance and ADAMS simulation of the oscillating sieve and return pan of a rice combine harvester. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2018, 11, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomiyama, K.; Kawamura, A. Application of lifting wavelet transform for pavement surface monitoring by use of a mobile profilometer. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2016, 9, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimaunahan, E.D.; Abo, K.A.P.; Ricafort, C.D.; Gabayeron, X.R.; Teope, L.M.L. Road Surface Quality Assessment Using Fast-Fourier Transform. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 12th International Conference on Humanoid, Nanotechnology, Information Technology, Communication and Control, Environment, and Management (HNICEM), Manila, Philippines, 3–7 December 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Jiang, J.; Fichera, S.; Paoletti, P.; Layzell, L.; Mehta, D.; Luo, S. Road surface defect detection—From image-based to non-image-based: A survey. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 10581–10603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küçükkülahlı, E.; Erdoğmuş, P.; Polat, K. Histogram-based automatic segmentation of images. Neural Comput. Appl. 2016, 27, 1445–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akagic, A.; Buza, E.; Omanovic, S.; Karabegovic, A. Pavement crack detection using Otsu thresholding for image segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2018 41st International Convention on Information and Communication Technology, Electronics and Microelectronics (MIPRO), Opatija, Croatia, 21–25 May 2018; pp. 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, B.M.S.; Majety, V.D.; Pittala, C.S.; Vijay, V.; Sandeep, K.S.; Kiran, S. Road Identification Through Efficient Edge Segmentation Based on Morphological Operations. Trait. Du Signal 2021, 38, p1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Ding, S.; Xu, X.; Nie, R. The latest research progress on spectral clustering. Neural Comput. Appl. 2014, 24, 1477–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Wen, W.; Wu, S.; Zheng, C.; Lu, X.; Chang, W.; Xiao, P.; Guo, X. 3D reconstruction of wheat plants by integrating point cloud data and virtual design optimization. Agriculture 2024, 14, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Guo, H.; Tian, X.; Wu, Z. Intelligent tuning of fractional-order PID control for performance optimization in active suspension systems. J. Vib. Control 2025, 10775463251348002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, D.; Guo, T.; Yu, S.; Liu, W.; Li, L.; Sun, Z.; Peng, H.; Hu, D. Classification of Apple Color and Deformity Using Machine Vision Combined with CNN. Agriculture 2024, 14, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, H.-C.; Zeng, H.-F.; Zhu, Z.-H.; Bai, G.-W.; Cao, W. Methodology for interactive labeling of patched asphalt pavement images based on U-Net convolutional neural network. Sustainability 2022, 14, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wu, J.; Li, P. Real-time detection and location of potted flowers based on a ZED camera and a YOLO V4-tiny deep learning algorithm. Horticulturae 2021, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, S.; Bai, Q.; Yang, J.; Jiang, S.; Miao, Y. Review of image classification algorithms based on convolutional neural networks. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Wang, W.; Gu, J.; Xia, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, B. Research on apple object detection and localization method based on improved YOLOX and RGB-D images. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachmanus, S.; Ravankar, A.A.; Emaru, T.; Kobayashi, Y. Multi-modal sensor fusion-based semantic segmentation for snow driving scenarios. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 16839–16851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Cho, J. Convergence of Stereo Vision-Based Multimodal YOLOs for Faster Detection of Potholes. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2022, 73, p2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.-Y.; Dong, J.-F.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.-H. Adaptive fuzzy PID control strategy for vehicle active suspension based on road evaluation. Electronics 2022, 11, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, C.; Brilakis, I. Pothole detection in asphalt pavement images. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2011, 25, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Song, X.; Wu, J.; Liu, S.; Chen, X.; Guo, X. Road surface defects detection based on IMU sensor. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 22, 2711–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, S.; Takeuchi, K.; Shibata, K.; Horita, Y. A method to distinguish road surface conditions for car-mounted camera images at night-time. In Proceedings of the 2012 12th International Conference on ITS Telecommunications, Taipei, Taiwan, 5–8 November 2012; pp. 668–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, L.; Wang, L.; Zhang, P. Estimation of crop height distribution for mature rice based on a moving surface and 3D point cloud elevation. Agronomy 2022, 12, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.; Singh, A.K.; Lohani, B. Extraction of road surface from mobile LiDAR data of complex road environment. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2017, 38, 4655–4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wei, L.; Xu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, J.; Cai, Q.; Zhang, W. Stereo-vision-based multi-crop harvesting edge detection for precise automatic steering of combine harvester. Biosyst. Eng. 2022, 215, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Shao, L.; Xu, D.; Shotton, J. Enhanced computer vision with microsoft kinect sensor: A review. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2013, 43, 1318–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Li, Y.; Zhao, C.; Yao, D.; Chen, G.; Sun, L.; Krajnik, T.; Yan, Z. 3D ToF LiDAR in mobile robotics: A review. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.11025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikosaka, S.; Tonooka, H. Image-to-image subpixel registration based on template matching of road network extracted by deep learning. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, R.D.; Petruska, M.A.; Klimov, V.I. Tunable Near-Infrared Optical Gain and Amplified Spontaneous Emission Using PbSe Nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 13765–13768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Ai, X.; Dahnoun, N. Road Surface 3D Reconstruction Based on Dense Subpixel Disparity Map Estimation. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 27, 3025–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moscoso Thompson, E.; Ranieri, A.; Biasotti, S.; Chicchon, M.; Sipiran, I.; Pham, M.-K.; Nguyen-Ho, T.-L.; Nguyen, H.-D.; Tran, M.-T. SHREC 2022: Pothole and crack detection in the road pavement using images and RGB-D data. Comput. Graph. 2022, 107, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xue, X.; Chen, C.; Sun, Z.; Sun, T. Development of a low-cost quadrotor UAV based on ADRC for agricultural remote sensing. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2019, 12, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, N.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, F.; Wang, X. Advanced interferometric fiber optic gyroscope for inertial sensing: A review. J. Light. Technol. 2023, 41, 4023–4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Tian, X. Automatic cruise system for water quality monitoring. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2018, 11, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wu, J.; Pan, X.; Dou, H.; Zhao, X.; Gao, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhai, C. Design and Experiment of a Breakpoint Continuous Spraying System for Automatic-Guidance Boom Sprayers. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Hu, H.; Xing, S.; Li, Z. Efficient and fast real-world noisy image denoising by combining pyramid neural network and two-pathway unscented Kalman filter. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2020, 29, 3927–3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Yongchareon, S.; Knoche, M. A review on computer vision and machine learning techniques for automated road surface defect and distress detection. J. Smart Cities Soc. 2023, 1, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghandorh, H.; Boulila, W.; Masood, S.; Koubaa, A.; Ahmed, F.; Ahmad, J. Semantic segmentation and edge detection—Approach to road detection in very high resolution satellite images. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, L.; Huang, C.; Lu, Y.; Wang, C. A dynamic tire model based on HPSO-SVM. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2019, 12, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Hu, X.; Du, X.; Cai, J.; Jia, W.; Wu, C. UAV-Based Multispectral Winter Wheat Growth Monitoring with Adaptive Weight Allocation. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Dong, J.; Fang, H.; Li, B.; Zhai, K.; Ma, D.; Shen, Y.; Hu, H. 3D reconstruction and segmentation system for pavement potholes based on improved structure-from-motion (SFM) and deep learning. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 398, 132499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhou, J.; Liu, W.; Yue, R.; Shi, J.; Zhou, C.; Hu, J. SN-CNN: A Lightweight and Accurate Line Extraction Algorithm for Seedling Navigation in Ridge-Planted Vegetables. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, H.; Sun, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhang, W.; Sheng, J.; Zhang, Z. Weed detection in maize fields by UAV images based on crop row preprocessing and improved YOLOv4. Agriculture 2022, 12, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Yang, S.; Li, J.; Qi, J. Research on SLAM Localization Algorithm for Orchard Dynamic Vision Based on YOLOD-SLAM2. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Hu, W.; Tran, A.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, G.; Kruppa, H.; Zimmermann, R.; Ng, S.-K. Multimodal deep learning for robust road attribute detection. ACM Trans. Spat. Algorithms Syst. 2023, 9, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackel, T.; Wegner, J.D.; Schindler, K. Contour detection in unstructured 3D point clouds. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 1610–1618. [Google Scholar]

- Badurowicz, M.; Karczmarek, P.; Montusiewicz, J. Fuzzy extensions of isolation forests for road anomaly detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems (FUZZ-IEEE), Luxembourg, 11–14 July 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyiga, J.; Ogunbiyi, T.; Achas, M.; Olagunju, O.; Ashade, B. An Improved Mobile Sensing Algorithm for Potholes Detection and Analysis. Univ. Ibadan J. Sci. Log. ICT Res. 2024, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Mednis, A.; Strazdins, G.; Zviedris, R.; Kanonirs, G.; Selavo, L. Real time pothole detection using android smartphones with accelerometers. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Distributed Computing in Sensor Systems and Workshops (DCOSS), Barcelona, Spain, 27–19 June 2011; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-W.; Chen, C.-H.; Cheng, D.-Y.; Lin, C.-H.; Lo, C.-C. A Real-Time Pothole Detection Approach for Intelligent Transportation System. Math. Probl. Eng. 2015, 2015, 869627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rishiwal, V.; Khan, H. Automatic pothole and speed breaker detection using android system. In Proceedings of the 2016 39th International Convention on Information and Communication Technology, Electronics and Microelectronics (MIPRO), Opatija, Croatia, 30 May–3 June 2016; pp. 1270–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljaafreh, A.; Alawasa, K.; Alja’afreh, S.; Abadleh, A. Fuzzy inference system for speed bumps detection using smart phone accelerometer sensor. J. Telecommun. Electron. Comput. Eng. (JTEC) 2017, 9, 133–136. [Google Scholar]

- Pooja, P.; Hariharan, B. An early warning system for traffic and road safety hazards using collaborative crowd sourcing. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Communication and Signal Processing (ICCSP), Chennai, India, 6–8 April 2017; pp. 1203–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celaya-Padilla, J.M.; Galván-Tejada, C.E.; López-Monteagudo, F.E.; Alonso-González, O.; Moreno-Báez, A.; Martínez-Torteya, A.; Galván-Tejada, J.I.; Arceo-Olague, J.G.; Luna-García, H.; Gamboa-Rosales, H. Speed bump detection using accelerometric features: A genetic algorithm approach. Sensors 2018, 18, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, R.S.; Pasin, M.; Kozakevicius, A.; Monego, V. Pothole detection in asphalt: An automated approach to threshold computation based on the haar wavelet transform. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 43rd Annual Computer Software and Applications Conference (COMPSAC), Milwaukee, WI, USA, 15–19 July 2019; pp. 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekshmipathy, J.; Velayudhan, S.; Mathew, S. Effect of combining algorithms in smartphone based pothole detection. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2021, 14, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalushkov, T.; Shipkovenski, G.; Petkov, E.; Radoeva, R. Accelerometer Sensor Network for Reliable Pothole Detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 5th International Symposium on Multidisciplinary Studies and Innovative Technologies (ISMSIT), Ankara, Turkey, 21–23 October 2021; pp. 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Farid, Y.Z.; Ucar, S.; Sisbot, E.A.; Oguchi, K. A Vehicular-Network Based Speed-Bump Detection Approach. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Vehicular Networking Conference (VNC), Kobe, Japan, 29–31 May 2024; pp. 275–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Fu, W.; Ma, X.; Yu, J.; Li, X.; Dong, Z. Road surface pits and speed bumps recognition based on acceleration sensor. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 10669–10679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Haodong, P.; Xuchen, Z.; Wenjiang, L.; Tang, Z. Identification and depth determination of potholes based on vibration acceleration of vehicles. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2025, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, T.; Chen, T.; Zhang, X.; Taha, M.F.; Yang, N.; Mao, H.; Shi, Q. Cucumber downy mildew disease prediction using a CNN-LSTM approach. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, H.; Correia, P.L. Automatic road crack segmentation using entropy and image dynamic thresholding. In Proceedings of the 2009 17th European Signal Processing Conference, Glasgow, Scotland, 24–28 August 2009; pp. 622–626. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, M.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, S.; Chen, J. Improved piezoelectric grain cleaning loss sensor based on adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system. Precis. Agric. 2022, 23, 1174–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Yang, X.; Cheng, Z.; Zou, P.X.; Gong, J.; Ye, M. A novel moisture damage detection method for asphalt pavement from GPR signal with CWT and CNN. NDT E Int. 2024, 145, 103116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Qin, G.; Wang, X. Improvement of canny algorithm based on pavement edge detection. In Proceedings of the 2010 3rd International Congress on Image and Signal Processing, Yantai, China, 16–18 October 2010; pp. 964–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarneh, S.; Elghaish, F.; Al-Ghraibah, A.; Abdellatef, E.; Edwards, D.J. An automatic image processing based on Hough transform algorithm for pavement crack detection and classification. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2025, 14, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Liu, L.; Zhou, X.; Wang, C. Road detection algorithm of integrating region and edge information. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Robotics and the International Conference on Automation, Control and Robotics Engineering, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 20–22 April 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buza, E.; Omanovic, S.; Huseinovic, A. Pothole detection with image processing and spectral clustering. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Information Technology and Computer Networks, Antalya, Turkey, 8–10 October 2013; p. 4853. [Google Scholar]

- Kiran, A.G.; Murali, S. Automatic hump detection and 3D view generation from a single road image. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics (ICACCI), Delhi, India, 24–27 September 2014; pp. 2232–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.-K.; Kim, T.; Kim, Y.-R. Feature-based pothole detection in two-dimensional images. Transp. Res. Rec. 2015, 2528, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devapriya, W.; Babu, C.N.K.; Srihari, T. Advance driver assistance system (ADAS)-speed bump detection. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Computing Research (ICCIC), Madurai, India, 10–12 December 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiopu, I.; Saarinen, J.P.; Kettunen, L.; Tabus, I. Pothole detection and tracking in car video sequence. In Proceedings of the 2016 39th International Conference on Telecommunications and Signal Processing (TSP), Vienna, Austria, 27–29 June 2016; pp. 701–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devapriya, W.; Babu, C.N.K.; Srihari, T. Real time speed bump detection using Gaussian filtering and connected component approach. In Proceedings of the 2016 World Conference on Futuristic Trends in Research and Innovation for Social Welfare (Startup Conclave), Coimbatore, India, 29 February–1 March 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouma, Y.O.; Hahn, M. Pothole detection on asphalt pavements from 2D-colour pothole images using fuzzy c-means clustering and morphological reconstruction. Autom. Constr. 2017, 83, 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srimongkon, S.; Chiracharit, W. Detection of speed bumps using Gaussian mixture model. In Proceedings of the 2017 14th International Conference on Electrical Engineering/Electronics, Computer, Telecommunications and Information Technology (ECTI-CON), Phuket, Thailand, 27–30 June 2017; pp. 628–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Hu, Y.; Dai, Y.; Tian, M. Asphalt pavement pothole detection and segmentation based on wavelet energy field. Math. Probl. Eng. 2017, 2017, 1604130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, T.D.; Khan, M.A. Watershed-based real-time image processing for multi-potholes detection on asphalt road. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 9th International Conference on System Engineering and Technology (ICSET), Shah Alam, Malaysia, 7 October 2019; pp. 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirbu, C.L.; Tomoiu, C.; Fancsali-Boldizsar, S.; Orhei, C. Real-time line matching based speed bump detection algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 27th International Symposium for Design and Technology in Electronic Packaging (SIITME), Timisoara, Romania, 27–30 October 2021; pp. 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Li, Y.; Tian, Z.; Zhang, F. 2D and 3D object detection algorithms from images: A Survey. Array 2023, 19, 100305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.-K.; Choi, G.-S. Improved yolov5: Efficient object detection using drone images under various conditions. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Xie, Y.; Ding, M.; Yang, L.; Tomizuka, M.; Wei, Y. A road surface reconstruction dataset for autonomous driving. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Guo, Y. Toward real-time 3D object recognition: A lightweight volumetric CNN framework using multitask learning. Comput. Graph. 2018, 71, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhu, H. Evaluation of a laser scanning sensor in detection of complex-shaped targets for variable-rate sprayer development. Trans. ASABE 2016, 59, 1181–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazal, F.; Guibas, L.J.; Oudot, S.Y.; Skraba, P. Analysis of scalar fields over point cloud data. In Proceedings of the Twentieth Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms, New York, NY, USA, 4–6 January 2009; pp. 1021–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, C.; Gavilán, M.; Llorca, D.F.; Parra, I.; Quintero, R.; Lorente, A.G.; Vlacic, L.; Sotelo, M. Free space and speed humps detection using lidar and vision for urban autonomous navigation. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium, Alcala de Henares, Spain, 3–7 June 2012; pp. 698–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moazzam, I.; Kamal, K.; Mathavan, S.; Usman, S.; Rahman, M. Metrology and visualization of potholes using the microsoft kinect sensor. In Proceedings of the 16th International IEEE Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC 2013), Hague, The Netherlands, 6–9 October 2013; pp. 1284–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, S.; Marchetti, E.; Cassidy, S.; Hoare, E.; Bogoni, A.; Gashinova, M.; Cherniakov, M. 24 GHz interferometric radar for road hump detections in front of a vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2018 19th International Radar Symposium (IRS), Bonn, Germany, 20–22 June 2018; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.-C.; Chatterjee, A. Pothole detection and classification using 3D technology and watershed method. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2018, 32, 04017078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lion, K.M.; Kwong, K.H.; Lai, W.K. Smart speed bump detection and estimation with kinect. In Proceedings of the 2018 4th International Conference on Control, Automation and Robotics (ICCAR), Auckland, New Zealand, 20–23 April 2018; pp. 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Fan, J.; Guo, L.; Qiao, L.; Bhutta, M.U.M.; Hosking, B.; Vityazev, S.; Fan, R. Scale-adaptive pothole detection and tracking from 3-d road point clouds. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Imaging Systems and Techniques (IST), Online, 24–26 August 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Yue, D.; Li, S.; Cai, D.; Zhang, Y. Road potholes detection from MLS point clouds. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2023, 34, 095017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Chen, Y. Towards detecting speed bumps from MLS point clouds data. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, 48, 815–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Qiao, L.; Shen, Y. Pavement Potholes Quantification: A Study Based on 3D Point Cloud Analysis. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 12945–12955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Alzubaidi, L.; Zhang, J.; Duan, Y.; Gu, Y. A comparison review of transfer learning and self-supervised learning: Definitions, applications, advantages and limitations. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 242, 122807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, K.; Rane, C.; Sriram, R.; Manry, M. Unsupervised learning. In Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for EDGE Computing; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucheng, J.; Jizhan, L.; Zhujie, X.; Shouqi, Y.; Pingping, L.; Jizhang, W. Development status and trend of agricultural robot technology. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2021, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, Q.; Xu, W.; Xu, L.; Lu, E. Prediction of Feed Quantity for Wheat Combine Harvester Based on Improved YOLOv5s and Weight of Single Wheat Plant without Stubble. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, R.; Kumar, K. Yolo and RetinaNet Ensemble Transfer Learning Detector: Application in Pavement Distress. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computing, Communication and Learning, Warangal, India, 29–31 August 2023; pp. 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; He, X.; Ge, X.; Wu, X.; Shen, J.; Song, Y. Detection of key organs in tomato based on deep migration learning in a complex background. Agriculture 2018, 8, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouazizi, O.; Azroumahli, C.; El Mourabit, A.; Oussouaddi, M. Road object detection using ssd-mobilenet algorithm: Case study for real-time adas applications. J. Robot. Control (JRC) 2024, 5, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Deshmukh, C. Pothole and bump detection using convolution neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference (ITEC-India), Bengaluru, India, 17–19 December 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, P.; Yang, X.; Gao, Z. A deep learning approach for street pothole detection. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Sixth International Conference on Big Data Computing Service and Applications (BigDataService), Oxford, UK, 3–6 August 2020; pp. 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunpriyan, J.; Variyar, V.S.; Soman, K.; Adarsh, S. Real-time speed bump detection using image segmentation for autonomous vehicles. In Intelligent Computing, Information and Control Systems: ICICCS 2019; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 308–315. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Sharma, P.; Sharma, D.; Gupta, V.; Sambyal, N. Detection and localization of potholes in thermal images using deep neural networks. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2020, 79, 26265–26284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.O.; Variyar, V.S.; Soman, K. Speed bump segmentation an application of conditional generative adversarial network for self-driving vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2020 Fourth International Conference on Computing Methodologies and Communication (ICCMC), Erode, India, 11–13 March 2020; pp. 935–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewangan, D.K.; Sahu, S.P. Deep learning-based speed bump detection model for intelligent vehicle system using raspberry Pi. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 21, 3570–3578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, M.; Pitas, I. Graph attention layer evolves semantic segmentation for road pothole detection: A benchmark and algorithms. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 8144–8154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan Prakash, B.; Sriharipriya, K. Enhanced pothole detection system using YOLOX algorithm. Auton. Intell. Syst. 2022, 2, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugenti, A.; Vulpi, F.; Domínguez, R.; Cordes, F.; Milella, A.; Reina, G. On the role of feature and signal selection for terrain learning in planetary exploration robots. J. Field Robot. 2022, 39, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Gautam, A.; Basak, S.; Saxena, N. Yolov8 based deep learning method for potholes detection. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision and Machine Intelligence (CVMI), Gwalior, India, 10–11 December 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aishwarya, P.V.; Reddy, D.S.; Sonkar, D.K.; Koundinya, P.N.; Rajalakshmi, P. Robust deep learning based speed bump detection for autonomous vehicles in indian scenarios. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 26th International Symposium on Real-Time Distributed Computing (ISORC), Nashville, TN, USA, 23–25 May 2023; pp. 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, D.-H.; Choi, J.-Y.; Kim, S.-B.; Tak, T.-O.; Zhang, S.-P. Image-based pothole detection using multi-scale feature network and risk assessment. Electronics 2023, 12, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, A.A.; Omar, M.M.; Altamimi, J.S.; Ead, W.M. An Intelligent Approach for Speed Bump Detection. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Computing and Machine Intelligence (ICMI), Mt Pleasant, MI, USA, 13–14 April 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewangan, D.K.; Sahu, S.P.; Arya, K.V. Vision-Sensor Enabled Multilayer CNN Scheme and Impact Analysis of Learning Rate Parameter for Speed Bump Detection in Autonomous Vehicle System. IEEE Sens. Lett. 2024, 8, 6002504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodake, V.J.; Meeeshala, S.K. FTayCO-DCN: Fractional Taylored Crocuta Optimization Enabled Deep Convolutional Neural Network for Pothole Detection. In Proceedings of the 2025 6th International Conference on Mobile Computing and Sustainable Informatics (ICMCSI), Malmo, Sweden, 15 March 2025; pp. 1774–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandak, P.; Chaurasia, S.; Patil, M. Identification of Potholes and Speed Bumps Using SSD and YOLO. In International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Networking; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Dollár, K.H.G.G.P.; Girshick, R. Mask r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2961–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Li, S.; Jia, Y. Real-time object detection method based on improved YOLOv4-tiny. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2011.04244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joubert, D.; Tyatyantsi, A.; Mphahlehle, J.; Manchidi, V. Pothole Tagging System. 2011. Available online: https://researchspace.csir.co.za/server/api/core/bitstreams/5b05fc0f-e3dc-4c74-a3f2-ee8c443cbdb6/content (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Zhou, X.; Chen, W.; Wei, X. Improved Field Obstacle Detection Algorithm Based on YOLOv8. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.; Antony, J.K.; Isaac, A.V.; Aromal, M.; Verghese, S. A novel road attribute detection system for autonomous vehicles using sensor fusion. Int. J. Inf. Technol. 2025, 17, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yuan, C.; Liu, D.; Cai, H. Integrated processing of image and GPR data for automated pothole detection. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2016, 30, 04016015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.-h.; Choi, S.-i. Pothole detection system using 2D LiDAR and camera. In Proceedings of the 2017 Ninth International Conference on Ubiquitous and Future Networks (ICUFN), Milan, Italy, 4–7 July 2017; pp. 744–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, H.-S.; Kim, T.-H.; Park, T.-H. Speed-bump detection for autonomous vehicles by lidar and camera. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2019, 14, 2155–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaudeen, H.; Çelebi, E. Pothole Detection Using Image Enhancement GAN and Object Detection Network. Electronics 2022, 11, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman-Garay, M.; Rodriguez-Rangel, H.; Hernandez-Beltran, C.B.; Lepej, P.; Arreygue-Rocha, J.E.; Morales-Rosales, L.A. Architecture for pavement pothole evaluation using deep learning, machine vision, and fuzzy logic. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Chen, Z.; Song, H.; Dong, Y. Model predictive control for speed-dependent active suspension system with road preview information. Sensors 2024, 24, 2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, X.; Wang, L.-M.; Hou, J.-X.; Xue, Y.-Q.; Rao, S.-J.; Zhou, Z.-Y.; Jia, F.-X.; Zhang, Z.-Y.; Li, L.-M. Road recognition and stability control for unmanned ground vehicles on complex terrain. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 77689–77702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-H.; Kim, H.-J.; Cho, B.-J.; Choi, J.-H.; Kim, Y.-J. Road bump detection using LiDAR sensor for semi-active control of front axle suspension in an agricultural tractor. IFAC-Pap. 2018, 51, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seok, J.; Jo, J.; Kim, Y.; Kim, H.; Jung, I.; Jeong, M.; Kim, N.; Jo, K. LiDAR-based Road Height Profile Estimation and Bump Detection for Preview Suspension. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024; early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Na, Y.; Jung, M.; Lee, J.; Seok, J.; Kim, B.; Kim, H.; Jung, I.; Jo, K. Personalized Driving Data-based Bump Prediction Using a Cloud-based Continuous Learning for Preview Electronically Controlled Suspension. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024; early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitale, P.A.; Kekre, K.Y.; Shenai, H.R.; Karani, R.; Gala, J.P. Pothole detection and dimension estimation system using deep learning (yolo) and image processing. In Proceedings of the 2020 35th International Conference on Image and Vision Computing New Zealand (IVCNZ), Wellington, New Zealand, 25–27 November 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Ashfaque, M.; Ulhaq, M.U.; Mathavan, S.; Kamal, K.; Rahman, M. Pothole 3D reconstruction with a novel imaging system and structure from motion techniques. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 23, 4685–4694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Kale, A. P3De-a novel pothole detection algorithm using 3D depth estimation. In Proceedings of the 2021 2nd International Conference for Emerging Technology (INCET), Belagavi, India, 21–23 May 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, T.; Wang, X. Advanced pavement distress recognition and 3D reconstruction by using GA-DenseNet and binocular stereo vision. Measurement 2022, 201, 111760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranyal, E.; Sadhu, A.; Jain, K. AI assisted pothole detection and depth estimation. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Machine Intelligence for GeoAnalytics and Remote Sensing (MIGARS), Hyderabad, India, 27–29 January 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Randhawa, M.; Kalra, N.; Seth, C.; Gill, A.; Chopra, P.; Kaur, G. Pothole Sensing and Depth Estimation System using Deep Learning Technique. In Proceedings of the 2024 OPJU International Technology Conference (OTCON) on Smart Computing for Innovation and Advancement in Industry 4.0, Raigarh, India, 5–7 June 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-S.; Nguyen, N.-N. Two-camera vision technique for measuring pothole area and depth. Measurement 2025, 247, 116809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset Name | Description | Train | Validation | Test | Access Link |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Pothole-600 Dataset | Provide disparity maps converted using stereo matching algorithms | 239 | 179 | 179 | Google (https://sites.google.com/view/pothole-600/dataset; accessed on 1 September 2025) |

| Dib’s Pothole Detection Dataset | The first dataset with water-filled and dried pothole | 570 | 173 | / | Mendeley (https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/tp95cdvgm8; accessed on 1 September 2025) |

| PODS Dataset | Including potholes in various road environments | 1191 | 113 | 59 | Universe (https://universe.roboflow.com/pods/pothole-detection-x7dgh; accessed on 1 September 2025) |

| Abhinva Kulshreshth’s Pothole Detection Dataset | Contains both normal images and potholes images, combines of Google and Kaggle | 1167 | 108 | 136 | Kaggle (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/abhinavkulshreshth/pothole-detection-dataset; accessed on 1 September 2025) |

| Semantic Segmentation of Pothole and Cracks Dataset | A dataset focused on semantic segmentation | 3340 | 496 | 504 | DeepLearning (http://deeplearning.ge.imati.cnr.it/genova-5G/; accessed on 1 September 2025) |

| Japanese Road Damage Detection Dataset | Images of road damage instances captured using a mobile phone installed in the vehicle | 7718 | 4630 | 3087 | GitHub (https://github.com/sekilab/RoadDamageDetector; accessed on 1 September 2025) |

| Dataset Name | Description | Total Images | Access Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpeedHump/bumpDataset | Images of marked and unmarked speed bumps | 543 | Mendeley (https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/xt5bjdhy5g/1; accessed on 1 September 2025) |

| Marked Speed Bump/Speed Breaker Dataset (India) | Image of speed bumps on Indian roads | 969 | Mendeley (https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/bvpt9xdjz8/1; accessed on 1 September 2025) |

| ZIYA’s Speed Bump Detection Dataset | Including images of speed bumps, potholes, cracks and normal roads under various road conditions | 270 | Kaggle (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ziya07/speed-bump-dataset/data; accessed on 1 September 2025) |

| Universe Speed Bump Dataset (4) | Contains the images used for the object detection of the YOLO model | 593 | Universe (https://universe.roboflow.com/alia-khalifa/detecting-speed-bumps/dataset/4; accessed on 1 September 2025) |

| Universe Speed Bump Dataset (15) | One of the largest datasets for speed bumps object detection | 1692 | Universe (https://universe.roboflow.com/speed-bump-detection/speed-bump-detection-se0eh/dataset/15; accessed on 1 September 2025) |

| Authors | Date | Method | Descriptions | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mednis et al. (2011) [86] | Acceleration signal | Z-THRESH, Z-DIFF, STDEV(Z), G-ZERO | Four algorithms were used to analyze acceleration signals. Among them, the Z-DIFF algorithm achieved the best performance. | Positive rate: 99% |

| Wang et al. (2015) [87] | Acceleration signal, GPS | Normalization, Z-THRESH Spatial Interpolation Method, G-ZERO | Acceleration data were normalized to establish a reference angle, and the Z-THRESH and G-ZERO algorithms were integrated to enhance detection accuracy. | False positive: 0% |

| Rishiwal and Khan (2016) [88] | Acceleration signal | Z-axis acceleration threshold | By detecting the sudden change in Z-axis acceleration, combined with threshold detection and classification. | Accuracy: 93.75% |

| Aljaafreh et al. (2017) [89] | Acceleration signal | Fuzzy Inference System (FIS) | The fuzzy reasoning system detects speed bumps via vehicle vertical acceleration and speed changes. | / |

| Celaya-Padilla et al. (2018) [91] | Acceleration signal, gyroscope data, GPS | Genetic algorithm, cross-validation | Retrieving data from sensors, employing a cross-validation strategy, and using the genetic algorithm for speed bump detection. | Accuracy: 97.14% |

| Rodrigues et al. (2019) [92] | Acceleration signal | Haar wavelet transform (HWT), two-step thresholding procedure, adaptive threshold estimation | Wavelet coefficients are obtained via a two-step thresholding process, with adaptive threshold estimation employed instead of manual threshold calibration. | / |

| Lekshmipathy et al. (2021) [93] | Acceleration signal | High-pass filtering, algorithm combination | By determining the optimal combination and thresholds of different algorithms, the proposed algorithm-threshold combination achieved a true positive rate of 93.18%. | True positive: 93.18% False positive: 20% |

| Yin et al. (2024) [96] | Acceleration signal, GPS | Feature extraction filter (EFDD), least squares method, Euler point, wavelet technology, genetic algorithm | A new method for detecting speed bumps using accelerometers, GPS sensors, and feature extraction filters (EFDD) achieves 100% accuracy in speed bump detection. | Pothole accuracy: 75% Speed bumps accuracy: 75% |

| Zhang et al. (2025) [97] | Acceleration signal | Newmark method, particle swarm optimization algorithm | The acceleration when passing through potholes is derived by solving the vibration equation via the Newmark method, and pothole depth is inversely estimated using the particle swarm optimization algorithm. | Average error rate: 8.94% |

| Authors | Date | Method | Descriptions | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buza et al. (2013) [105] | Color image | Otsu’s threshold processing, spectral clustering algorithm | By using the data based on the histogram in the grayscale image, spectral clustering is employed to identify the potholes. | Accuracy: 81% |

| Kiran and Murali (2014) [106] | Color image | Canny edge detection, Hough transform, morphological processing | Speed bumps are detected using Canny edge detection, Hough transform, and morphological processing. | / |

| Ryu et al. (2015) [107] | Color image | Based on histogram, thresholding, geometric features | Using histograms and morphological closing operations, dark areas for pothole detection are extracted; pothole contours are extracted using geometric features. | Accuracy: 71.6% Precision: 85.3% Recall: 61.3% |

| Devapriya et al. (2015) [108] | Color image | Grayscale conversion, binarization, morphological processing, horizontal projection method | Speed bumps are detected using grayscale conversion, binarization, morphological processing, and the horizontal projection method. | Ture positive: 92% |

| Schiopu et al. (2016) [109] | Color image | Histogram-based threshold, geometric properties | Select the region of interest (ROI) and employ a threshold-based algorithm to generate it. | Precision: 90% Recall: 100% |

| Devapriya et al. (2016) [110] | Color image | Gaussian filtering, median filtering, connected region analysis | Methods using Gaussian filtering, median filtering, and connected region analysis to detect speed bumps yield relatively low detection accuracy for unmarked ones. | Accuracy: 85% |

| Ouma and Habn (2017) [111] | Color image | Wavelet transform, fuzzy c-means clustering, morphological reconstruction | Using wavelet transform to reduce noise, fuzzy C-means clustering extracts pothole areas, and morphological reconstruction optimizes pothole edge detection. | Accuracy: 87.5% |

| Srimongkon and Chiracharit (2017) [112] | Color image | Gaussian mixture model, morphological processing | Based on Gaussian mixture model segmentation and morphological operations, speed bumps are identified and detected. | Ture positive: 82.75% False positive: 17.25% |

| Wang et al. (2017) [113] | Grayscale Image | Wavelet energy field, Markov random field, morphological processing | Construct the wavelet energy field of road surface images, detect potholes using morphological processing, and perform segmentation using the Markov random fields. | Precision: 85.7% Recall: 72% F1: 78.3% |

| Sirbu et al. (2021) [115] | Color image | Gaussian filtering, semantic segmentation, ED line algorithm | Apply Gaussian filtering to smooth the image, extract the region of interest based on semantic segmentation, and use the ED algorithm for speed bump detection. | Accuracy: 71.6% Precision: 85.3% Recall: 61.3% |

| Authors | Date | Method | Descriptions | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fernández et al. (2012) [122] | 3D road point cloud | Coordinate system conversion, free space detection algorithm | LiDAR provides four horizontal layer measurements, combined with the free space detection algorithm to detect speed bumps. | Computed time: 6.48 ms |

| Moazzam et al. (2013) [123] | Depth image | Coordinate system transformation, trigonometric surveying method | The Kinect is used to capture depth images, enabling low-cost acquisition of pit depth without complex calculations. | Low cost |

| Melo et al. (2018) [124] | Radar scanning data | Interferometric measurement method, SFCW | Innovative integration of radar interferometry with SFCW enables effective speed bump detection and height measurement. | height estimation error less than 5% |

| Tsai and Chatterjee (2018) [125] | 3D road surface data | Data correction, watershed algorithm | The collected 3D road data are corrected, with potholes detected via the watershed algorithm. | Accuracy: 94.97% Precision: 90.80% Recall: 98.75% |

| Lion et al. (2018) [126] | Color images, depth images | Three-dimensional scene reconstruction, morphological processing, Canny edge detection | Using the Kinect to obtain ground color and depth images enables three-dimensional scene reconstruction, enabling effective detection of speed bumps’ height and distance. | Accuracy: 86.84% |

| Wu et al. (2021) [127] | 3D road point cloud | GPT-SGM, Three-Stage Normal Filter (3F2N), Discriminative Scale Space Tracking (DSST) Algorithm | Fitting a quadratic surface to the 3D road point cloud and comparing it with the actual 3D road point cloud extracts the pothole point cloud. The DSST algorithm is then used to detect the potholes. | Accuracy: 98.7% |

| Ma et al. (2023) [128] | Mobile laser scanning data | Directed distance, skew distribution, density clustering | Combining directed distance calculation with density clustering for the singularization and denoising of potholes, potholes are detected using the negative skew distribution and skewness coefficient of the directed distance histogram. | Accuracy: 91% Recall: 82% |

| Fan and Chen (2023) [129] | Mobile laser scanning data | PointNet, PointCNN, region-growing algorithm | Based on MLS point cloud data, a comparison was conducted between deep learning algorithms and the region-growing algorithm. | Recall: 89.2% IoU: 0.82 |

| Sun et al. (2025) [130] | 3D point cloud | Voxel filtering, RANSAC, Euclidean clustering, Alpha Shapes algorithm | Voxel filtering is used for noise reduction, RANSAC and Euclidean clustering for point cloud segmentation, and the Alpha Shapes algorithm for 3D reconstruction to detect potholes and estimate their volumes. | Accuracy: 96.4% |

| Authors | Date | Method | Descriptions | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shah and Deshmukh (2019) [138] | Color image | ResNet-50, YOLO | Using the ResNet-50 network to classify normal roads, speed bumps, and potholes from images achieves a true positive rate (TPR) of 88.9%. | True positive: 88.9% |

| Arunpriyan et al. (2020) [140] | Color image | Data augmentation, SegNet | SegNet, a semantic segmentation deep CNN, has 91.781% global accuracy but performs poorly in detecting unmarked speed bumps and vertical-view images. | Accuracy: 91.781% MIoU: 48.872 |

| Gupta et al. (2020) [141] | Thermal image | ResNet34-SSD, ResNet50-RetinaNet | Innovatively combining thermal images with deep learning for pothole detection, the improved ResNet50-RetinaNet achieves 91.15% average precision. | Accuracy: 91.15% |

| Dewangan and Sahu (2020) [143] | Color image | Self-built CNN, distance estimation algorithm based on pixel changes | A deep learning and computer vision-based speed bump detection model is proposed, achieving 98.54% accuracy, 99.05% precision, and 97.89% F1-score in real-time scenarios. | Accuracy: 98.54% Precision: 99.05% F1-score: 97.89% |

| Fan et al. (2021) [144] | RGB image, disparity image, transformed disparity image | SoAT CNNs, GAL-DeepLabv3+ | The first stereo vision-based road pothole monitoring dataset and a new disparity transformation algorithm have been released. The GAL-DeepLabv3+ model achieves the highest overall detection accuracy across all data modalities. | Precision: 89.819% Accuracy: 98.669% Recall: 83.205% F1-score: 89.802% |

| Mohan and Sriharipriya (2022) [145] | Color image | YOLOX-Nano | A pioneering study introduces the first application of the YOLOX object detection model to pothole detection, achieving 85.6% average precision with the lightweight YOLOX-Nano variant, which occupies only 7.22 MB of storage. | Precision: 85.6% Size: 7.22 MB |

| Aishwarya et al. (2023) [148] | Color image | Faster R-CNN, YOLOv5, Negative Sample Training (NST) | State-of-the-art Faster R-CNN and YOLOv5 models were used, with the negative sample training (NST) method enhancing detection accuracy—achieving 5.58% and 2.3% increases for significant speed bumps, respectively. | Accuracy: 98.8% Size: 42.2 MB |

| Hussein et al. (2024) [150] | Color image | Data augmentation, YOLOv8 | The YOLOv8n model performs best in detecting both labeled and unlabeled speed bumps, with an average precision (mAP) of 0.81. This method integrates a Kinect Xbox camera on the Jetson Nano developer kit to enable distance estimation for detected speed bumps. | Precision: 82% Recall: 79% |

| Bodake and Meeeshala (2025) [152] | Color image | FTayCO-DCN, Panoramic Image Conversion, Grayscale Conversion | The integrated framework combining the improved FTayCO algorithm and the DCN classification model achieves pothole detection with 99.06% accuracy, 99.09% sensitivity, and 99.04% specificity. | Accuracy: 99.06% Sensitivity: 99.09% Specificity: 98.33% |

| Chandak et al. (2024) [153] | Color image | YOLOv4, SSD-MobileNet, data augmentation | A comparative analysis of YOLOv4 and SSD-MobileNet reveals that SSD-MobileNet exhibits superior performance in terms of accuracy (0.42), recall (0.81), and F1-score (0.82). Additionally, SSD-MobileNet outperforms YOLOv4 in inference efficiency, with an inference time of 7 ms compared to 52.51 ms for YOLOv4. | Precision: 85.48% Recall: 81% F1-score: 82% |

| Authors | Date | Method | Descriptions | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joubert et al. (2011) [156] | 3D point cloud, color image | Random Sample Consensus algorithm, contour detection | Integrates 3D point clouds with high-speed USB-captured images; uses RANSAC to separate road surface from depression point clouds and edge detection to calculate depression width/depth. | / |

| Li et al. (2016) [159] | 2D images, GPR data | Image processing, based on geometric active contour model | Integrates 2D images and GPR data; estimates pothole location/size from GPR data, maps them to image. | Accuracy: 88% Recall: 90% Precision: 94.7% |

| Kang and Chio (2017) [160] | 2D radar point cloud, color image | Median filtering, Gaussian blurring algorithm, Canny edge detection | 2D LiDAR acquires road distance/angle information; through noise filtering, clustering, line extraction, and data gradient analysis, obtains pothole contours. | / |

| Yun et al. (2019) [161] | 2D images, 3D point clouds | Image binarization, Gaussian filtering, median filtering, Harr, HOG, SVM | Uses two detectors to extract/verify speed bumps: extracts speed bump candidate regions via image patterns; detects speed bump area/height via point cloud data, HOG, and SVM. | Precision: 88% Recall: 95% F1-score: 91% |

| Salaudeen and Celebi (2022) [162] | Color Image (Low Resolution and Super-Resolution) | ESRGAN, YOLOv5, EfficientDet | Super-resolution reconstruction of low-resolution road images at 4× scale is performed using ESRGAN. Subsequently, two object detection models, YOLOv5 and EfficientDet, are employed for training and inference on the enhanced high-resolution images. | Precision: 97.6% Recall: 70% |

| Roman-Garay (2025) [163] | 2D images, 3D point clouds | Segformer, RANSAC, Fuzzy Logic Model | Creates dataset with 2D images/3D point clouds; uses transfer learning (Segformer) to achieve 90.87% recall, 90.01% accuracy, 90.43% F1 score. | Accuracy: 90.01% Recall: 90.87% F1-score: 90.43% |

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional dynamics | Easy to deploy, low cost | Poor real-time performance |

| 2D Image Processing | Simplicity, low cost | Sensitive to lighting conditions and road conditions |

| 3D Point Cloud Analysis | Detailed surface information | Computational complexity, high equipment costs |

| Machine/Deep Learning | High detection accuracy, high robustness, high reliability | Requires a large amount of training data |

| Multi-sensor fusion methods | Higher accuracy, robustness | Increased complexity, integration challenges |

| Method | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional dynamics | 85% | / | / | Low |

| 2D Image Processing | 76% | 69% | 70% | Low |

| 3D Point Cloud Analysis | 85% | 84% | 83% | High |

| Machine/Deep Learning | 88% | 86% | 87% | Medium |

| Multi-sensor fusion methods | 91% | 87% | 90% | High |

| Authors | Date | Method | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chitale et al. (2020) [169] | Color image | YOLOv3, YOLOv4, Triangular Similarity Based on Image Processing | The YOLOv4 model exhibits excellent performance, with an mAP of 0.933 and IoU of 0.741. Combined with the triangular similarity principle, pothole depth can be estimated, with an error of 5.868%. |

| Ahmed et al. (2021) [170] | Dynamic image | High-pass filtering, Gaussian filtering, SIFT feature matching, laser triangulation measurement | Using SIFT feature matching and the 5-point algorithm, a 3D point cloud is generated. Under static imaging conditions, the average depth and perimeter errors are 5.3% and 5.2%, respectively. |

| Das and Kale (2021) [171] | Live video | CNN, RPN, frequency heatmap calibration | The method combines CNN and RPN, converting real-time video into a VIBGYOR color scale heatmap via frequency heatmap calibration to enhance system adaptability to complex environments. |

| Li et al. (2022) [172] | Stereo image | Binocular stereo vision, three-dimensional reconstruction, genetic algorithm | Combining binocular stereo vision, 3D pothole features are extracted using point cloud interpolation and plane fitting algorithms, achieving depth and area detection with average accuracies of 98.9% and 98%, respectively. |

| Wang et al. (2023) [78] | Multi-view 2D images | PP-SFM algorithm, Trans-3DSeg | An approach based on PP-SFM generates 3D point clouds, with the Trans-3DSeg model for training. Under low-light conditions, segmentation accuracy is 91.86% and F1 score is 92.13%. |

| Ranyal et al. (2023) [173] | 2D image | Improving CNN architecture–RetinanNet, motion structure photogrammetry technology | An intelligent pavement detection system employs the improved CNN RetinanNet. It uses motion structure photogrammetry to simulate pothole 3D point clouds, achieving an F1 score up to 98% on the dataset with average pothole depth estimation error below 5%. |

| Singh et al. (2024) [174] | Color image | Faster RCNN Resnet 50 FPN | The Faster R-CNN ResNet-50 FPN model achieves training and validation accuracies of 96% and 85%, respectively. Using image processing and ultrasonic sensors, pothole depth can be estimated. |

| Park and Nguyan (2025) [175] | Color image | YOLOv8-seg, optical geometric principles | Using binocular vision, the YOLOv8 instance segmentation model, and optical geometry principles, real-time pothole area and depth are calculated with average error below 5%. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shen, Y.; Jing, K.; Sun, K.; Liu, C.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y. Review of Uneven Road Surface Information Perception Methods for Suspension Preview Control. Sensors 2025, 25, 5884. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25185884

Shen Y, Jing K, Sun K, Liu C, Yang Y, Liu Y. Review of Uneven Road Surface Information Perception Methods for Suspension Preview Control. Sensors. 2025; 25(18):5884. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25185884

Chicago/Turabian StyleShen, Yujie, Kai Jing, Kecheng Sun, Changning Liu, Yi Yang, and Yanling Liu. 2025. "Review of Uneven Road Surface Information Perception Methods for Suspension Preview Control" Sensors 25, no. 18: 5884. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25185884

APA StyleShen, Y., Jing, K., Sun, K., Liu, C., Yang, Y., & Liu, Y. (2025). Review of Uneven Road Surface Information Perception Methods for Suspension Preview Control. Sensors, 25(18), 5884. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25185884