When Teratology and Augmented Reality Entwine: A Qualitative Phenomenological Analysis in a Museal Setting

Abstract

Highlights

- This is the first qualitative study that shows insights that were encountered when using AR in a teratological collection;

- Both (bio)medical students and general visitors are interested in using AR in an educational and museal setting;

- Teratological exhibitions may enhance public awareness and acceptance of developmental anomalies.

- Teratological exhibitions provide a unique opportunity to reflect on both historical and contemporary bioethical issues;

- It was suggested that AR can provide better insights into teratology and create a more interactive way of learning.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Creation of the AR Models

2.3. Participants and Recruitment

2.4. Study Design

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Results of the Analysis for (Bio)Medical Students

3.2.1. Theme 1: Views on the Teratological Collection

Additional Value of the Collection

“I think these specimens are especially informative because you can see what can go wrong on the outside. Then you realize that it does not only exist in books, but that it also happens in real life.”(P3, age 26)

Feelings of Unease and Inconvenience

“I find it very sad... If you’re the mother of such a child, it must be so strange. You expect to bring a healthy baby into the world, but then you give birth to a deceased child that’s also completely deformed.”(P8, age 23)

Ethical Aspects

“I think that not only medical students, but also other groups should know about congenital abnormalities and that things don’t always go well.”(P10, age 23)

“You can say that it is not allowed or wrong or that we shouldn’t do it. But on the other hand, what do you do with them then? I think that now it has already happened, and we can learn valuable information from them.”(P7, age 20)

Knowledge and Prevention

“Each time when you see it again, it’s strange to realize it does not always go well. We are lucky when it does go well.”(P14, age 21)

“It is something that doctors should learn and understand, because it exists. And because they have to be able to provide information to parents if it happens to them.”(P7, age 20)

3.2.2. Theme 2: Positive and Negative Aspects of AR

Positive Aspects: Positive Experience

“It was a lot of fun. I had never done this before, so I found it exceptional that this was even possible and how it’s all made. I think it adds to the experience.”(P12, age 22)

Positive Aspects: Interactive

Positive Aspects: Insightful

“It’s amazing that you can walk around it, that you can grab it, turn it, that you can take the structures out and enlarge them.”(P2, age 27)

Negative Aspects: Logistics

Negative Aspects: Feeling Watched

“There are all these people around me who are not wearing the AR devices, who are just visiting the museum. And I’m there, looking strange with these devices and movements.”(P1, age 24)

“Putting on the glasses and launching the systems is a bit weird. It feels strange because you are in a room, and you have the idea someone is watching you while you’re doing all these things in the air.”(P2, age 27)

3.2.3. Theme 3: The Use of AR in a Teratological Collection

Impact on Museum Visit

“I think this is less shocking for people. So, I think that it’s also more approachable. If people find the specimens really scary, I think this could be more approachable for them.”(P9, age 24)

AR as an Alternative or Addition to Specimens

“I think it’s a good addition to see them next to each other. You have the specimen and that’s what it looks like on the outside. And then you can visualize it even more with the models.”(P3, age 26)

“With the specimens I have the feeling I am looking at someone’s child. With the AR modalities, I am looking at a learning object.”(P13, age 25)

3.2.4. Theme 4: Recommendations on Using AR Devices in Museum Tours and Teratology Education

User-Friendliness of the AR Device

“I had to practice a bit. It’s as they say in German: Fingerspitzengefühl.”(P1, age 24)

Didactics

Tips and Tricks

3.3. Results of the Analysis for General Visitors

3.3.1. Theme 1: Views on the Teratological Collection

Positive Attitude Toward the Collection

“…you spend more time looking at a specimen and then it’s mainly interesting and fascinating to see. It makes you think on how it is possible that something can grow like that.”(P1, age 24)

Negative Feelings and Uneasiness

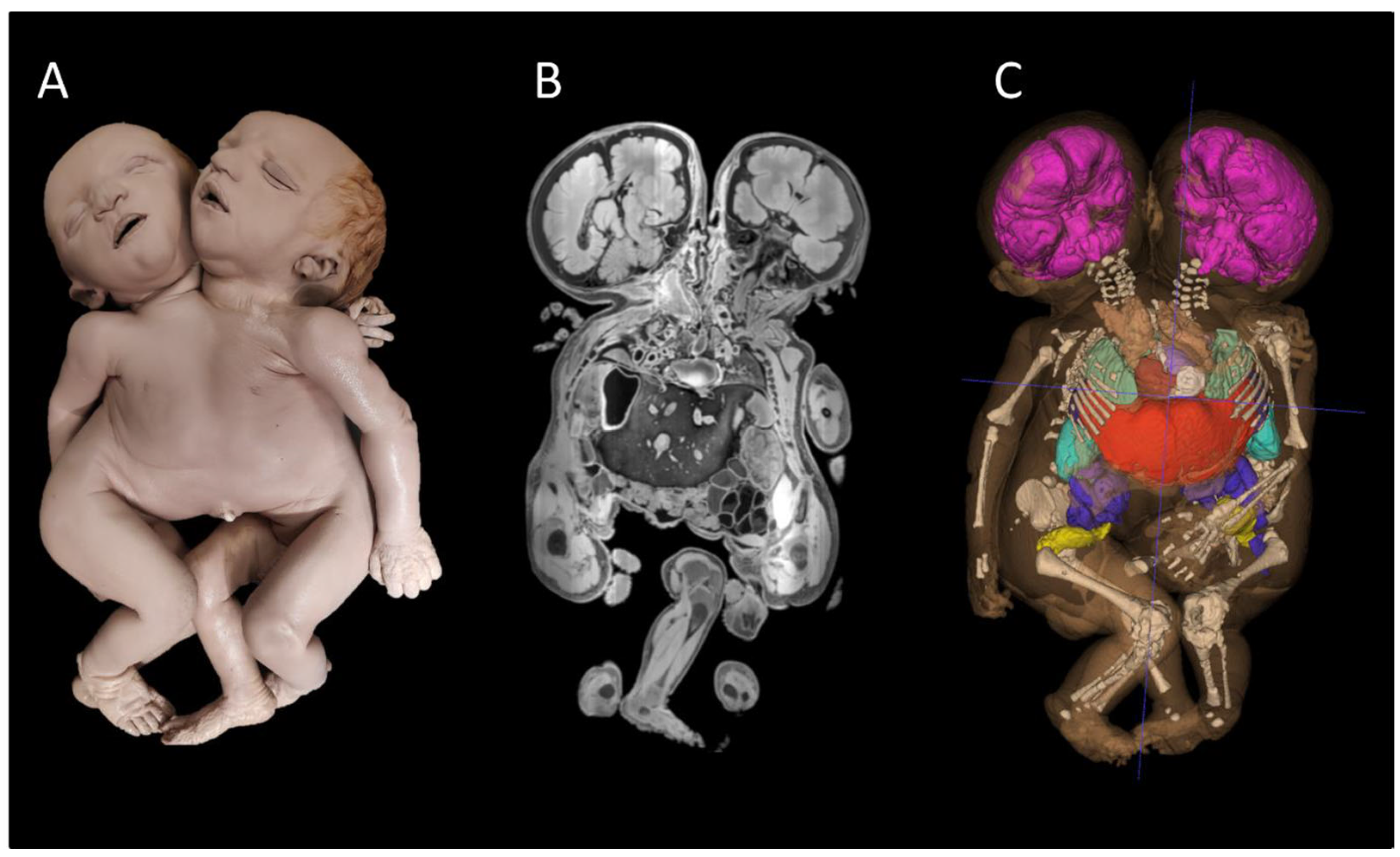

“This one with the two heads on one body, it looks a bit monstruous.”(P6, age 54)

Relevance for the Visitor

“…you see it and interpret it as a simple, technical soul. But you don’t really know what to do with it. I mean you don’t know much about it. And without information you won’t get very far.”(P3, age 22)

Ethical Aspects

“If people look at it the right way, then I find it very positive. And educational. But it shouldn’t be a circus attraction. That’s what we had in the past. That was the only way to see them, at the fair.”(P4, age 73)

“I think that we shouldn’t use the current ethical standards on things that were different in the past. I think we often go too far with that. I think it’s good for people that they can see it in real life.”(P10, age 25)

Knowledge and Prevention

“I want to become a mother too. And when you see this, you realize there are a lot of things that can go wrong.”(P10, age 25)

Purposes and Use of the Collection

3.3.2. Theme 2: Additional Value of AR

Positive Experience with AR

Learning Efficiency and Insightfulness

“It is impressive that you can actually see the reason it’s not viable. With the baby with the two heads on one body, you can actually see that it only has one heart.”(P12, age 25)

Creating Awareness

Use of the AR Technique

3.3.3. Theme 3: Use of AR in a Teratological Museum

Museum Purposes of AR

“A museum is mainly for enjoyment and conveying information. Education means further development…”(P1, age 24)

Ethical Aspects

“It looks a bit artificial. That’s why I think the combination, AR as an addition would be good. Because people need to remain aware of the ethical dilemmas and that these are human beings.”(P6, age 54)

Impact on the Museum Visit

“I think it is a way to get rid of your fear. Because you’re always scared of things you don’t know. So, if you know more about it, it becomes less scary…”(P12, age 25)

3.3.4. Theme 4: Use of AR in Teratology Education

Educational Purposes of AR

“Education means further development… I think in education you can go more into depth. And this shouldn’t be the intention of the museum without offering that in-depth information in the medical curriculum.”(P1, age 24)

AR as an Alternative or Addition to Specimens

3.3.5. Theme 5: Improvements and Recommendations on AR

User-Friendliness of the AR Devices

“It’s like learning a game and after 15 min you know how to play it.”(P4, age 73)

Information on the AR Models

“When you’re using it, it’s interactive, but you don’t know what structures… What you are grabbing. I don’t know. There are probably people that do know. People who are medically versed.”(P5, age 53)

Technical Developments

3.3.6. Theme 6: Logistics When Implementing AR

“I think glasses like this need to be renewed every once in a while. So, you will have to look at the financial picture. If it gets outdated, costs come into play.”(P8, age 56)

4. Discussion

Teratological Specimens: An Ethical Issue for Museums?

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boer, L.L.; Boek, P.L.; van Dam, A.J.; Oostra, R.J. History and highlights of the teratological collection in the Museum Anatomicum of Leiden University, The Netherlands. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2018, 176, 618–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boer, L.L.; Kircher, S.G.; Rehder, H.; Behunova, J.; Winter, E.; Ringl, H.; Scharrer, A.; de Boer, E.; Oostra, R.J. History and highlights of the teratological collection in the Narrenturm, Vienna (Austria). Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2023, 191, 1301–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oostra, R.J.; Schepens-Franke, A.N.; Magno, G.; Zanatta, A.; Boer, L.L. Conjoined twins and conjoined triplets: At the heart of the matter. Birth Defects Res. 2022, 114, 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boer, L. The Past, Present and Future of Dutch Teratological Collections. From Enigmatic Specimens to Paradigm Breakers. 2019. Available online: https://repository.ubn.ru.nl/bitstream/handle/2066/206293/206293.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Moxham, B.J.; Emmanouil-Nikoloussi, E.; Standley, H.; Brenner, E.; Plaisant, O.; Brichova, H.; Pais, D.; Stabile, I.; Borg, J.; Chirculescu, A. The attitudes of medical students in Europe toward the clinical importance of embryology. Clin. Anat. 2016, 29, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, L.L.; de Rooy, L.; Oostra, R.J. Dutch teratological collections and their artistic portrayals. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 2021, 187, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovendeert, J.F.M.; Nievelstein, R.A.J.; Bleys, R.L.A.W.; Cleypool, C.G.J. A parapagus dicephalus tripus tribrachius conjoined twin with a unique morphological pattern: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2020, 14, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, L.L.; Schepens-Franke, A.N.; van Asten, J.J.A.; Bosboom, D.G.H.; Kamphuis-van Ulzen, K.; Kozicz, T.L.; Ruiter, D.J.; Oostra, R.J.; Klein, W.M. Radiological imaging of teratological fetuses: What can we learn? Insights Imaging 2017, 8, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harthoorn, F.S.; Scharenborg, S.W.J.; Brink, M.; Peters-Bax, L.; Henssen, D.J.H.A. Students’ and junior doctors’ perspectives on radiology education in medical school: A qualitative study in the Netherlands. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- vom Lehn, D. The body as interactive display: Examining bodies in a public exhibition. Sociol. Health Illn. 2006, 28, 223–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwall, J.; Champney, T.H.; de la Cova, C.; Hall, D.; Hildebrandt, S.; Mussell, J.C.; Winkelmann, A.; DeLeon, V.B. American Association for Anatomy recommendations for the management of legacy anatomical collections. Anat. Rec. 2024, 307, 2787–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourniquet, S.E.; Beiter, K.J.; Mussell, J.C. Ethical Rationales and Guidelines for the Continued Use of Archival Collections of Embryonic and Fetal Specimens. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2019, 12, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdecasas, A.G.; Correia, V.; Correas, A. Museums at the crossroad: Contributing to dialogue, curiosity and wonder in natural history museums. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2006, 21, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, L.M. The rise and demise of a collection of human fetuses at Mount Holyoke College. Perspect. Biol. Med. 2006, 49, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Haddad, J.; Štrkalj, G.; Pather, N. A global perspective on embryological and fetal collections: Where to from here? Anat. Rec. 2022, 305, 869–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.G. The use of human tissue: An insider’s view. N. Z. Bioeth. J. 2002, 3, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D.G.; Gear, R.; Galvin, K.A. Stored human tissue: An ethical perspective on the fate of anonymous, archival material. J. Med. Ethics 2003, 29, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marreez, Y.M.A.-H.; Willems, L.N.A.; Wells, M.R. The role of medical museums in contemporary medical education. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2010, 3, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, B.M. Embryology in the medical curriculum. Anat. Rec. 2002, 269, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillon, A.B.; Marchal, I.; Houlier, P. Mobile augmented reality in the museum: Can a lace-like technology take you closer to works of art? In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality—Arts, Media, and Humanities, Basel, Switzerland, 26–29 October 2011; pp. 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.A.; Lai, H.I. Application of augmented reality in museums—Factors influencing the learning motivation and effectiveness. Sci. Prog. 2021, 104 (Suppl. 3), 368504211059045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, A.; Kitama, T.; Toyoura, M.; Mao, X. The Use of Augmented Reality Technology in Medical Specimen Museum Tours. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2019, 12, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogali, S.R.; Vallabhajosyula, R.; Ng, C.H.; Lim, D.; Ang, E.T.; Abrahams, P. Scan and Learn: Quick Response Code Enabled Museum for Mobile Learning of Anatomy and Pathology. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2019, 12, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yushkevich, P.A.; Piven, J.; Hazlett, H.C.; Smith, R.G.; Ho, S.; Gee, J.C.; Gerig, G. User-guided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: Significantly improved efficiency and reliability. NeuroImage 2006, 31, 1116–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutherland, J.; Belec, J.; Sheikh, A.; Chepelev, L.; Althobaity, W.; Chow, B.J.W.; Mitsouras, D.; Christensen, A.; Rybicki, F.J.; La Russa, D.J. Applying Modern Virtual and Augmented Reality Technologies to Medical Images and Models. J. Digit. Imaging 2019, 32, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson, M.; Smith, S. A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med. Image Anal. 2001, 5, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson, M.; Bannister, P.; Brady, M.; Smith, S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage 2002, 17, 825–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G. The Constant Comparative Method of Qualitative Analysis. Soc. Probl. 1965, 12, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sale, J.E.M. The role of analytic direction in qualitative research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2022, 22, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, D. The future of medical museums: Threatened but not extinct. Med. J. Aust. 2007, 187, 380–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temme, J.E.V. Amount and Kind of Information in Museums: Its Effects on Visitors Satisfaction and Appreciation of Art. Vis. Arts Res. 1992, 18, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- George, O.; Foster, J.; Xia, Z.; Jacobs, C. Augmented Reality in Medical Education: A Mixed Methods Feasibility Study. Cureus 2023, 15, e36927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhar, P.; Rocks, T.; Samarasinghe, R.M.; Stephenson, G.; Smith, C. Augmented reality in medical education: Students’ experiences and learning outcomes. Med. Educ. Online 2021, 26, 1953953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bork, F.; Lehner, A.; Eck, U.; Navab, N.; Waschke, J.; Kugelmann, D. The Effectiveness of Collaborative Augmented Reality in Gross Anatomy Teaching: A Quantitative and Qualitative Pilot Study. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2021, 14, 590–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henssen, D.J.H.A.; van den Heuvel, L.; De Jong, G.; Vorstenbosch, M.A.T.M.; van Cappellen van Walsum, A.M.; Van den Hurk, M.M.; Kooloos, J.G.M.; Bartels, R.H.M.A. Neuroanatomy Learning: Augmented Reality vs. Cross-Sections. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2020, 13, 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Rios, M.D.; Paredes-Velasco, M.; Beleño, R.D.H.; Fuentes-Pinargote, J.A. Analysis of emotions in the use of augmented reality technologies in education: A systematic review. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2023, 31, 216–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugelmann, D.; Stratmann, L.; Nühlen, N.; Bork, F.; Hoffmann, S.; Samarbarksh, G.; Pferschy, A.; von der Heide, A.M.; Eimannsberger, A.; Fallavollita, P.; et al. An Augmented Reality magic mirror as additive teaching device for gross anatomy. Ann. Anat. 2018, 215, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullinane, D.P.; Franklin, C.; Barry, D.S. Reviving the anatomic past: Breathing new life into historic anatomical teaching tools. J. Anat. 2023, 242, 701–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urlings, J.; Abma, I.; Aquarius, R.; Aalbers, M.; Bartels, R.; Maal, T.; Henssen, D.; Boogaarts, J. Augmented reality-The way forward in patient education for intracranial aneurysms? A qualitative exploration of views, expectations and preferences of patients suffering from an unruptured intracranial aneurysm regarding augmented reality in patient education. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1204643. [Google Scholar]

- Neb, A.; Brandt, D.; Awad, R.; Heckelsmüller, S.; Bauernhansl, T. Usability study of a user-friendly AR assembly assistance. Procedia CIRP 2021, 104, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSesso, J.M. The arrogance of teratology: A brief chronology of attitudes throughout history. Birth Defects Res. 2019, 111, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson-Marten, P.; Rich, B.A. A historical perspective of informed consent in clinical practice and research. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 1999, 15, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulczyński, J.; Paluchowski, P.; Halasz, J.; Szarszewski, A.; Bukowski, M.; Iżycka-Świeszewska, E. An insight into the history of anatomopathological museums. Part 2. Pol. J. Pathol. 2018, 69, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monza, F.; Cusella, G.; Ballestriero, R.; Zanatta, A. New life to Italian university anatomical collections: Desire to give value and open museological issues. Cases compared. Pol. J. Pathol. 2019, 70, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | (Bio)Medical Students | General Visitors |

| Gender | ||

| -Male (n) | 1 | 4 |

| -Female (n) | 13 | 8 |

| Age | ||

| -Age range | 20–27 years | 22–73 years |

| -Median age | 24 years | 27.5 years |

| Previous experience in the museum | ||

| -Present (n) | 14 | 1 |

| -Not present (n) | 0 | 11 |

| Previous experience with AR | ||

| -Present (n) | 3 | 2 |

| -Not present (n) | 11 | 10 |

| Years of (bio)medical education | ||

| -1st year (n) | 0 | / |

| -2nd year (n) | 3 | / |

| -3rd year (n) | 1 | / |

| -4th year (n) | 2 | / |

| -5th year (n) | 2 | / |

| -6th year (n) | 6 | / |

| Occupational status | ||

| -Working (n) | / | 5 |

| -Non-working (unable, etc.) (n) | / | 2 |

| -Student from non-(bio)medical faculty (n) | / | 3 |

| -Retired (n) | / | 2 |

| Themes | Categories |

|---|---|

| Views on the teratological collection. | Additional value of the collection |

| Feelings of unease and inconvenience | |

| Ethical aspects | |

| Knowledge and prevention | |

| Positive and negative aspects of AR | Positive aspects: positive experience, interactive and insightful |

| Negative aspects: logistics and feeling watched | |

| The use of AR in a teratological collection | Impact on museum visit |

| AR as an alternative or addition to specimens | |

| Recommendations on using AR devices in museum tours and teratology education | User-friendliness of the AR device |

| Didactics | |

| Tips and tricks |

| Themes | Categories |

|---|---|

| Views on the teratological collection | Positive attitude toward the collection |

| Negative feelings and uneasiness | |

| Relevance for the visitor | |

| Ethical aspects | |

| Knowledge and prevention | |

| Purposes and use of the collection | |

| Additional value of AR | Positive experience with AR |

| Learning efficiency and insightfulness | |

| Creating awareness | |

| Use of AR technique | |

| Use of AR in a teratological museum | Museum purposes of AR |

| Ethical aspects | |

| Impact on museum visit | |

| Use of AR in teratology education | Educational purposes of AR |

| AR as an alternative of addition to specimens | |

| Improvements and recommendations on AR | User-friendliness of the AR devices |

| Information on the AR models | |

| Technical developments | |

| Logistics when implementing AR | / |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boer, L.L.; Schol, F.; Christiaans, C.; Duits, J.; Maal, T.; Henssen, D. When Teratology and Augmented Reality Entwine: A Qualitative Phenomenological Analysis in a Museal Setting. Sensors 2025, 25, 3683. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25123683

Boer LL, Schol F, Christiaans C, Duits J, Maal T, Henssen D. When Teratology and Augmented Reality Entwine: A Qualitative Phenomenological Analysis in a Museal Setting. Sensors. 2025; 25(12):3683. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25123683

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoer, Lucas L., Frédérique Schol, Colin Christiaans, Jacobus Duits, Thomas Maal, and Dylan Henssen. 2025. "When Teratology and Augmented Reality Entwine: A Qualitative Phenomenological Analysis in a Museal Setting" Sensors 25, no. 12: 3683. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25123683

APA StyleBoer, L. L., Schol, F., Christiaans, C., Duits, J., Maal, T., & Henssen, D. (2025). When Teratology and Augmented Reality Entwine: A Qualitative Phenomenological Analysis in a Museal Setting. Sensors, 25(12), 3683. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25123683