Analysis of Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems for Safe and Comfortable Driving of Motor Vehicles

Abstract

1. Introduction

- increasing driving safety;

- improvement of driving comfort.

2. Description and Operation of Sensors in Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems

2.1. Radar Sensors

2.2. A Camera or Set of Cameras

2.3. LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging)

2.4. Ultrasounds

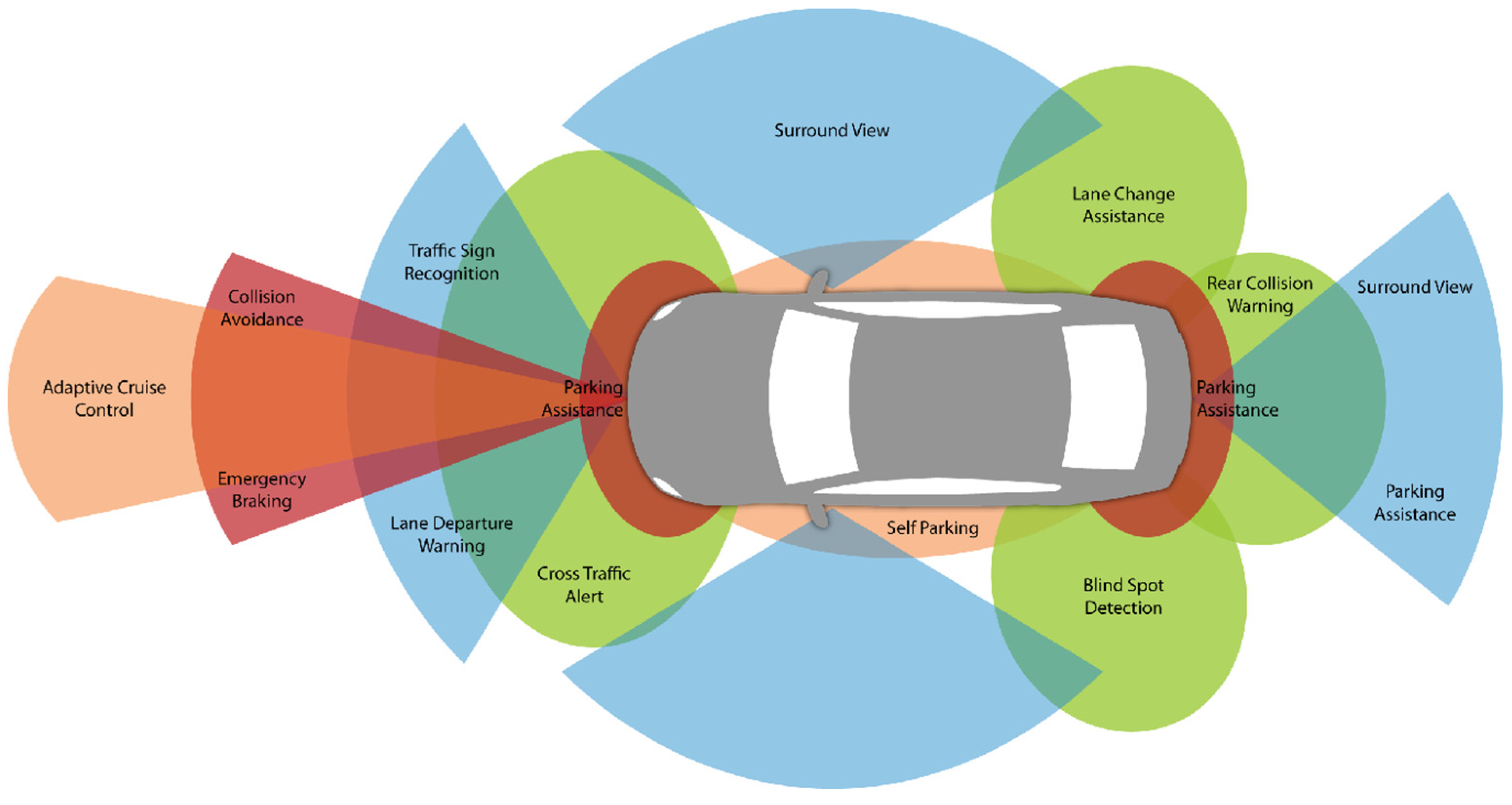

3. The Most Popular Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems Found in Cars on European Roads

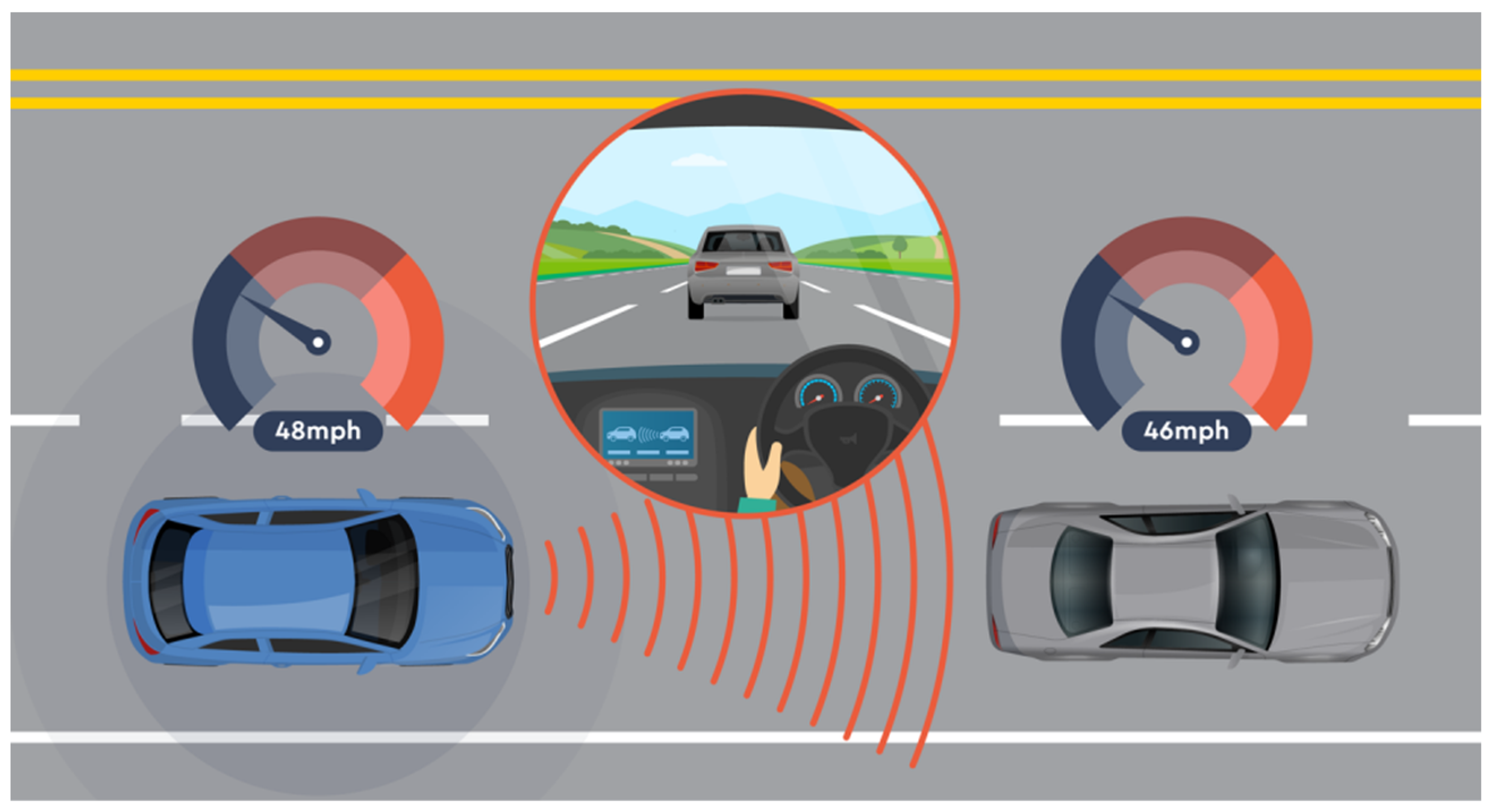

3.1. Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC)

3.2. Blind Spot Detection System—BSD

3.3. Lane Maintenance System—LDW/LKS

- Passive LDW systems that only warn of danger;

- Active LDW systems that combine warnings with light steering or braking corrections;

- LKS systems with full control that signal danger and actively keep the vehicle in the lane.

3.4. Intelligent Headlamp Control—IHC

- Systems with automatic headlight switching—the simplest form of IHC involves automatic switching between low and high beams. The main purpose of this type of system is to prevent dazzling oncoming drivers by automatically reducing light intensity in appropriate situations;

- Adaptive front lighting systems—these are advanced IHC systems that adjust the angle and intensity of the headlights depending on various factors, such as vehicle speed, driving direction, and general environmental conditions. They are designed to provide optimal road illumination, increasing driving safety;

- Cornering lighting systems—these systems illuminate the road when maneuvering around bends. These systems actively direct light in the direction the vehicle is facing by directing the headlights according to the steering angle. They provide better visibility around corners and at intersections, which is especially useful when driving at night.

3.5. EBA Driving Assistance System

- Basic EBA—this is a type of EBA system that focuses mainly on increasing the braking force when it detects a sudden need for the driver to brake. It does not include advanced predictive features or is integrated with other vehicle safety systems;

- EBA with Threat Detection EBA—more advanced EBA systems not only support braking, but also actively monitor the vehicle’s surroundings to detect potential threats early. They can use sensors, radars, or cameras to assess the road situation and respond to threats early;

- Adaptive EBA—these systems are capable of adapting their response depending on driving conditions, such as vehicle speed, road conditions, and even the behavior of other vehicles on the road. They are more flexible and can provide a more varied response in different situations;

- Integrated EBA—these are systems that are integrated with other vehicle safety systems, such as collision warning systems, lane keeping systems, or adaptive cruise control. These integrated systems can offer a more comprehensive security solution by analyzing and responding to a wider range of sensory data;

- EBA with Autonomous Emergency Braking EBA—this is the most advanced form of EBA, which can initiate emergency braking on its own, even if the driver does not respond to warnings. This is particularly useful in situations where the driver’s reaction time may be insufficient to avoid a collision;

4. Assessment of the Effectiveness of ADASs in the Area of Safety and Driving Comfort in the Opinion of Drivers

4.1. The Role of Driver-Assistance Systems in Improving Road Safety

4.2. The Impact of Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems in Improving Driving Comfort

4.3. The Impact of ADASs on the Sense of Safety and Driving Comfort—Survey Study

- What type of car do you have?

- What ADAS systems are installed in your car?

- How often do you use ADAS systems while driving?

- Do you think ADAS systems increase your sense of safety while driving?

- Do ADAS systems affect your driving comfort?

- Do you have any experiences where ADAS systems helped avoid an accident or dangerous situation?

- Do you have any comments or suggestions for improving ADAS systems?

4.4. Discussion

- Positive impacts on driver health:

- Reduced stress and fatigue: ADAS automates many tasks, such as keeping the vehicle in lane, adaptive cruise control, or automatic emergency braking, which reduces the cognitive load on the driver and reduces the stress associated with driving, especially on long journeys or in city traffic.

- Increased safety: ADASs help avoid accidents, which directly translates into a reduced risk of physical injury to the driver and passengers.

- Support in difficult conditions: Systems such as blind spot detection, forward collision warning, or automatic beam adjustment help the driver respond better to changing road conditions, which can reduce stress and the risk of accidents.

- Potential negative effects:

- ADAS dependency: Drivers may become overly reliant on assistance systems, which can lead to reduced driving skills and reduced ability to react quickly in emergency situations when ADASs may not function properly.

- Increased distraction: Automation of certain tasks can lead to drivers being more distracted, such as using phones or other devices, which can increase the risk of accidents in situations where ADASs are unable to respond appropriately.

- Risk of inaccurate information: Some ADASs may generate false alarms or incorrect warnings, which can lead to unnecessary stress or, in extreme cases, poor driver decisions.

- Physical health impacts:

- Exposure to electromagnetic radiation: ADASs use various technologies such as radars, cameras, and sensors that can emit electromagnetic radiation. The health impacts of long-term exposure are not fully understood, although current levels are considered safe.

- Posture and ergonomic changes: Reduced engagement in driving can lead to a less active driving posture, which can have long-term impacts on physical health, such as spine problems.

5. ADASs Systems Failure

- Automatic Emergency Braking (AEB) Failure. Description: The AEB system may fail to respond to an obstacle on the road, potentially leading to a collision. This could be due to software glitches, sensor malfunctions, or environmental conditions (e.g., fog, heavy rain) that interfere with sensor performance. Example: In 2020, some car models experienced issues with their AEB systems, leading to false alarms or failure to react in real emergency situations.

- Lane Keeping Assist (LKA) Failure. Description: The lane keeping assist system may stop working or malfunction, causing unintended lane departures. This could happen due to problems with cameras or sensors failing to detect lane markings properly, particularly in the case of poor lighting conditions, dirty sensors, or poorly maintained road markings. Example: Certain vehicles have been reported to have issues where the system fails to recognize lane markings in rain or bright sunlight, causing the system to deactivate unexpectedly.

- Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC) Failure. Description: Adaptive cruise control might not correctly adjust the vehicle’s speed in response to traffic. For example, the system may fail to detect a vehicle ahead or may not react to sudden speed changes, increasing the risk of a collision. Example: Some vehicles have experienced problems where the ACC does not respond to sudden stops by vehicles ahead, especially at high speeds on highways.

- Blind Spot Monitoring (BSM) Failure. Description: The Blind Spot Monitoring system may fail to detect vehicles in the driver’s blind spot, potentially leading to dangerous lane changes. This could be caused by sensor malfunctions, electromagnetic interference, or adverse weather conditions that affect radar performance. Example: There have been cases where the Blind Spot Monitoring system failed to detect vehicles next to the driver’s car, leading to risky maneuvers when changing lanes.

- Traffic Sign Recognition System Failure. Description: The Traffic Sign Recognition system may fail to correctly identify road signs or provide incorrect information. This could result from software errors, camera issues, or poor weather conditions like rain, fog, or low visibility. Example: In some instances, these systems have incorrectly identified speed limit signs, leading to improper speed suggestions for the driver.

- False Alarms. Description: ADASs may generate false alarms, warning the driver of non-existent hazards. This can lead to unnecessary stress or risky maneuvers. Example: False collision warnings or false detections of vehicles in the blind spot could cause sudden, unwarranted actions like abrupt braking or lane changes.

- Software Update Issues. Description: ADASs may malfunction due to errors during software updates. An improperly executed update can cause the systems to operate incorrectly or not at all. Example: After a software update, some ADASs in vehicles might malfunction or fail to activate, requiring service intervention.

6. Comparison of Different ADAS System Architectures

- 1.

- Centralized ArchitectureIn a centralized architecture, all sensor data are transmitted to a central processing unit for analysis and decision-making. Advantages: Unified data processing: Easier to synchronize and fuse data from multiple sensors; high computational power: The central processing unit can be more powerful, allowing for more complex algorithms; simplified maintenance: Only one core unit needs to be updated or maintained. Disadvantages: Latency issues: High data traffic can lead to communication delays, especially with high-resolution sensors like cameras and LiDAR; single point of failure: If the central processor fails, the entire system can go down; scalability: May not scale efficiently with an increasing number of sensors or sensor types.

- 2.

- Distributed ArchitectureIn a distributed architecture, sensors have local processing units and only transmit results (or partial data) to a central system. Advantages: Reduced latency: Local processing reduces the need for constant communication with the central unit; scalability: Easier to add more sensors since each sensor handles its own processing; robustness: Failure of one sensor or processing unit does not affect the entire system. Disadvantages: Synchronization challenges: Harder to synchronize data across sensors; increased power consumption: Local processing at each sensor requires more power; Higher cost: each sensor needs to be equipped with local processing capabilities.

- 3.

- Hybrid ArchitectureA hybrid architecture combines aspects of centralized and distributed systems, where some sensors have local processing while others rely on the central unit. Advantages: Flexibility: You can choose which sensors need local processing based on the application; optimized performance: Balance between reduced latency and computational power by distributing the workload; fault tolerance: Part of the system can still function if one section fails. Disadvantages: Complexity: More difficult to design and maintain than purely centralized or distributed systems; cost: Can be more expensive to implement, depending on the sensors used.

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raviteja, S.; Shanmughasundaram, R. Advanced Driver Assitance System (ADAS). In Proceedings of the 2018 Second International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems (ICICCS), Madurai, India, 14 June 2018; pp. 737–740. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, C.; Sridhar, P.; Madhumitha, R.; Sushmitha, R. Advanced Driver Assistance System (ADAS) in Autonomous Vehicles: A Complete Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2023 8th International Conference on Communication and Electronics Systems (ICCES), Coimbatore, India, 1 June 2023; pp. 1501–1505. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, I.S.; Casimiro, A.; Cecílio, J. Artificial Neural Networks for Real-Time Data Quality Assurance. Ada Lett. 2022, 42, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeba, M.; Bohumel, S.; Hrnčár, J.; Galinski, M.; Kotuliak, I. Small and Affordable Platform for Research and Education in Connected, Cooperative and Automated Mobility. In Proceedings of the 2023 21st International Conference on Emerging eLearning Technologies and Applications (ICETA), Stary Smokovec, Slovakia, 26–27 October 2023; pp. 225–230. [Google Scholar]

- Łukasik, Z.; Kuśmińska-Fijałkowska, A.; Olszańska, S. Strategy for the Implementation of Transport Processes toward Improving Services. Zesz. Nauk. Transp./Politech. Śląska 2023, 118, 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Zhu, K.; Liu, J.; Peng, C.; Wang, Y.; Lu, J. Adaptive Memory Event Triggered Output Feedback Finite-Time Lane Keeping Control for Autonomous Heavy Truck with Roll Prevention. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unar, S.; Su, Y.; Liu, P.; Teng, L.; Wang, Y.; Fu, X. An Intelligent System to Sense Textual Cues for Location Assistance in Autonomous Vehicles. Sensors 2023, 23, 4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, F.; Han, X.; Jiang, C.; Liu, J.; Peng, C. Fuzzy Dynamic Output Feedback Force Security Control for Hysteretic Leaf Spring Hydro-Suspension With Servo Valve Opening Predictive Management Under Deception Attack. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2022, 30, 3736–3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expósito, I.; Chin, I.; García Sánchez, M.; Cuiñas, I.; Verhaevert, J. Car Bumper Effects in ADAS Sensors at Automotive Radar Frequencies. Sensors 2023, 23, 8113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, G.; Cecílio, J.; Casimiro, A. Cooperative Autonomous Driving in Simulation. Ada Lett. 2023, 43, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orłowski, Ł.; Wszeborowski, R. Bezpieczeństwo w ruchu drogowym. Syst. Logistyczne Wojsk 2020, 53, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisaj, A. Model of Radio-Communications Platform Supporting Inland Navigation. TransNav Int. J. Mar. Navig. Saf. Sea Transp. 2024, 18, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexiev, K.; Slavcheva, N. A Method for Target Localization by Multistatic Radars. In Proceedings of the Modelling and Development of Intelligent Systems, Sibiu, Romania, 28–30 October 2022; Simian, D., Stoica, L.F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 89–103. [Google Scholar]

- Jarzemski, J.; Szagajew, L. Radar antykolizyjny. Probl. Tech. Uzbroj. 2006, 35, 211–216. [Google Scholar]

- Choromański, W.; Grabarek, I.; Kozłowski, M.; Czerepicki, A.; Marczuk, K. Pojazdy Autonomiczne i Systemy Transportu Autonomicznego; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN SA: Warszawa, Poland, 2020; ISBN 978-83-01-21154-7. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Yan, J.; Chen, H.; Zheng, K. Radar-Camera Fusion Network for Depth Estimation in Structured Driving Scenes. Sensors 2023, 23, 7560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, L.; Haider, A.; Kastner, L.; Zeh, T.; Poguntke, T.; Kuba, M.; Schardt, M.; Jakobi, M.; Koch, A.W. Velocity Estimation from LiDAR Sensors Motion Distortion Effect. Sensors 2023, 23, 9426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podbucki, K. Możliwości i ograniczenia monitorowania otoczenia z wykorzystaniem czujnika LiDAR. Przegląd Elektrotechniczny 2022, 98, 184–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, W.; Son, M.; Yoo, J.; Lee, S. Optimal Configuration of Multi-Task Learning for Autonomous Driving. Sensors 2023, 23, 9729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowotyńska, I. Systemy wspomagające bezpieczeństwo w transporcie drogowym. Autobusy Tech. Eksploat. Syst. Transp. 2013, 14, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.; Sun, H.; Tong, J.; Lin, M.; Li, J.; Liang, L.; Yin, F.; Xie, M.; et al. 3D Ultrasonic Brain Imaging with Deep Learning Based on Fully Convolutional Networks. Sensors 2023, 23, 8341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solanke, S. Project 2 Adaptive Cruise Control. Available online: https://skill-lync.com/student-projects/project-2-adaptive-cruise-control-5 (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Koznowski, W.; Łebkowski, A. Control of Electric Drive Tugboat Autonomous Formation. TransNav Int. J. Mar. Navig. Saf. Sea Transp. 2023, 17, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Zhu, Z.; Qin, J.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, H.; Fan, Y.; Liu, C.; Niu, W.; Li, S. Research on Construction of the Smart Internet of Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Power, Intelligent Computing and Systems (ICPICS), Shenyang, China, 29 July 2021; pp. 338–341. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao-Yun, L.; Hedrick, J.K.; Drew, M. ACC/CACC-Control Design, Stability and Robust Performance. In Proceedings of the 2002 American Control Conference (IEEE Cat. No.CH37301), Anchorage, AK, USA, 8–10 May 2002; Volume 6, pp. 4327–4332. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiev, K.; Tkachenko, I.; Ivanushkin, M.; Volgin, S. Telemetry Information Restoring in Satellite Communications. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Computer Systems and Technologies, Ruse, Bulgaria, 21–23 December 2018; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanna, K. Blind Spot Detection System Using Deep Learning. Available online: https://devpost.com/software/blind-spot-detection-using-deep-learning (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Bilik, D.; Lehoczký, P.; Kotuliak, I. Simulating Vehicle-to-Vehicle (V2V) Communication in Urban Traffic Scenarios. In Proceedings of the 2023 21st International Conference on Emerging eLearning Technologies and Applications (ICETA), Stary Smokovec, Slovakia, 26–27 October 2023; pp. 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Krzyszkowska, P. Nowoczesne systemy bezpieczeństwa stosowane w pojazdach i ich wpływ na bezpieczeństwo uczestników ruchu drogowego. Bezpieczeństwo Pr. Nauka I Prakt. 2015, 9, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiński, T. Pojazdy zautomatyzowane w aspekcie zrównoważonej mobilności miejskiej. Gospod. Mater. I Logistyka 2021, 2021, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICT Group Intelligently Controlling Headlight Beams. Available online: https://www.ict.eu/en/projects/intelligently-controlling-headlight-beams (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Canadian Underwriter The One Technology the Industry Can’t Wait to See Grow. Available online: https://www.canadianunderwriter.ca/insurance/the-one-technology-the-industry-cant-wait-to-see-grow-1004167271/attachment/emergency-braking-assist-eba-sysyem-to-avoid-car-crash-concept-smart-car-technology-3d-rendering-image/ (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Budziszewski, P. Autonomiczny system awaryjnego hamowania–działanie. Bezpieczeństwo Pr. Nauka I Prakt. 2015, 5, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brożyna, E. Czynnik ludzki a bezpieczeństwo w ruchu drogowym. Autobusy Tech. Eksploat. Syst. Transp. 2017, 18, 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Tęczyńska, E.; Dudek, T. Bezpieczeństwo a wykorzystanie inteligentnych systemów wspomagających kierowcę. Autobusy Tech. Eksploat. Syst. Transp. 2017, 18, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Gorzelańczyk, P.; Kaczmarek, Ł. Wpływ nowoczesnych systemów informatycznych na eksploatację pojazdów osobowych. Autobusy Tech. Eksploat. Syst. Transp. 2019, 20, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perzyńska, A.; Gliński, H.; Sokalska, A.; Śliwiński, Ł. Nowoczesne systemy bezpieczeństwa w transporcie drogowym. Przedsiębiorczość I Zarządzanie 2019, 20, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kłos-Adamkiewicz, Z. Nowoczesne technologie wspomagające bezpieczeństwo w transporcie. Probl. Transp. I Logistyki 2010, 10, 111–124. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Neumann, T. Analysis of Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems for Safe and Comfortable Driving of Motor Vehicles. Sensors 2024, 24, 6223. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24196223

Neumann T. Analysis of Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems for Safe and Comfortable Driving of Motor Vehicles. Sensors. 2024; 24(19):6223. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24196223

Chicago/Turabian StyleNeumann, Tomasz. 2024. "Analysis of Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems for Safe and Comfortable Driving of Motor Vehicles" Sensors 24, no. 19: 6223. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24196223

APA StyleNeumann, T. (2024). Analysis of Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems for Safe and Comfortable Driving of Motor Vehicles. Sensors, 24(19), 6223. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24196223