Defect Analysis in a Long-Wave Infrared HgCdTe Auger-Suppressed Photodiode

Abstract

1. Introduction

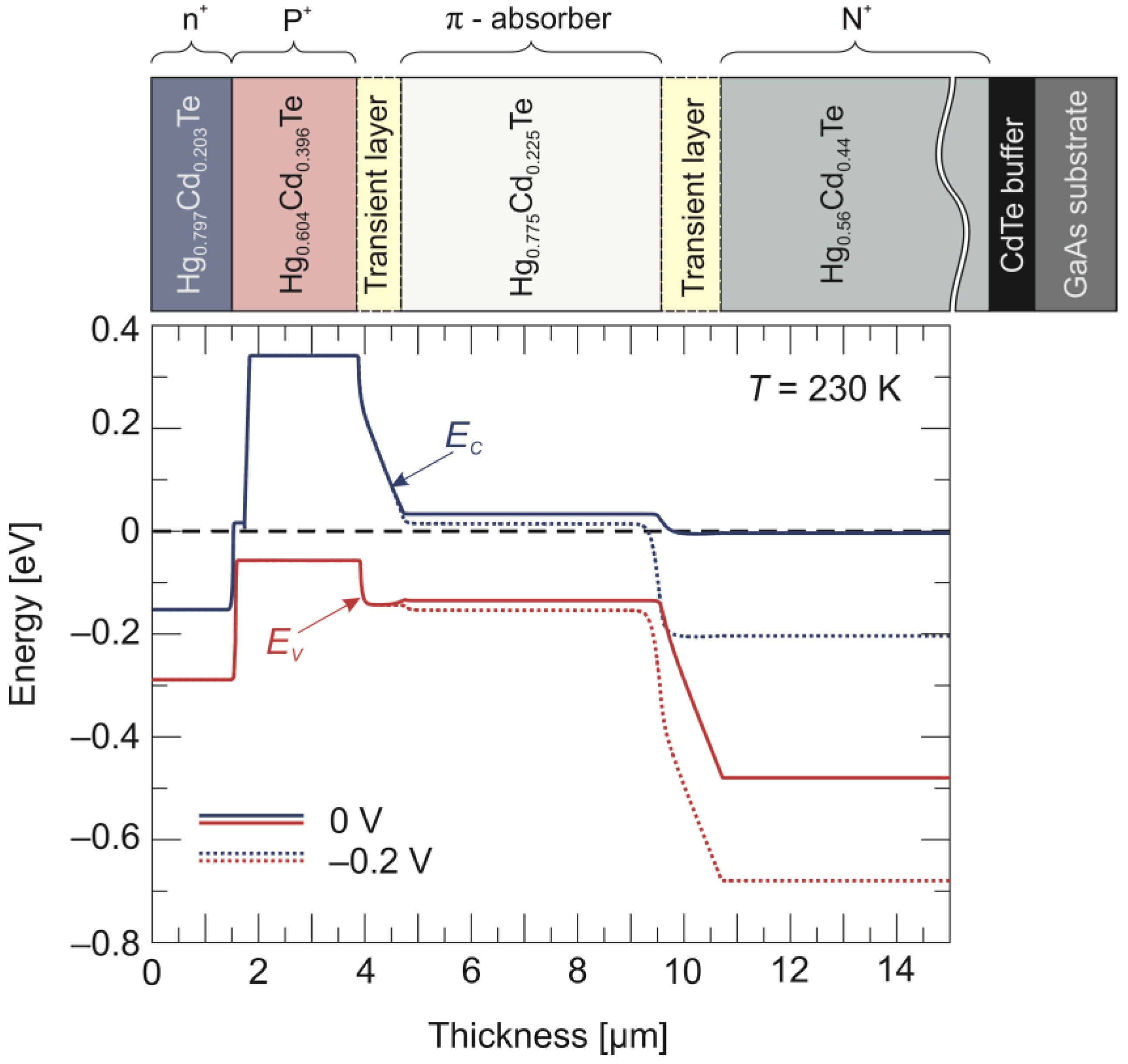

2. Materials and Methods

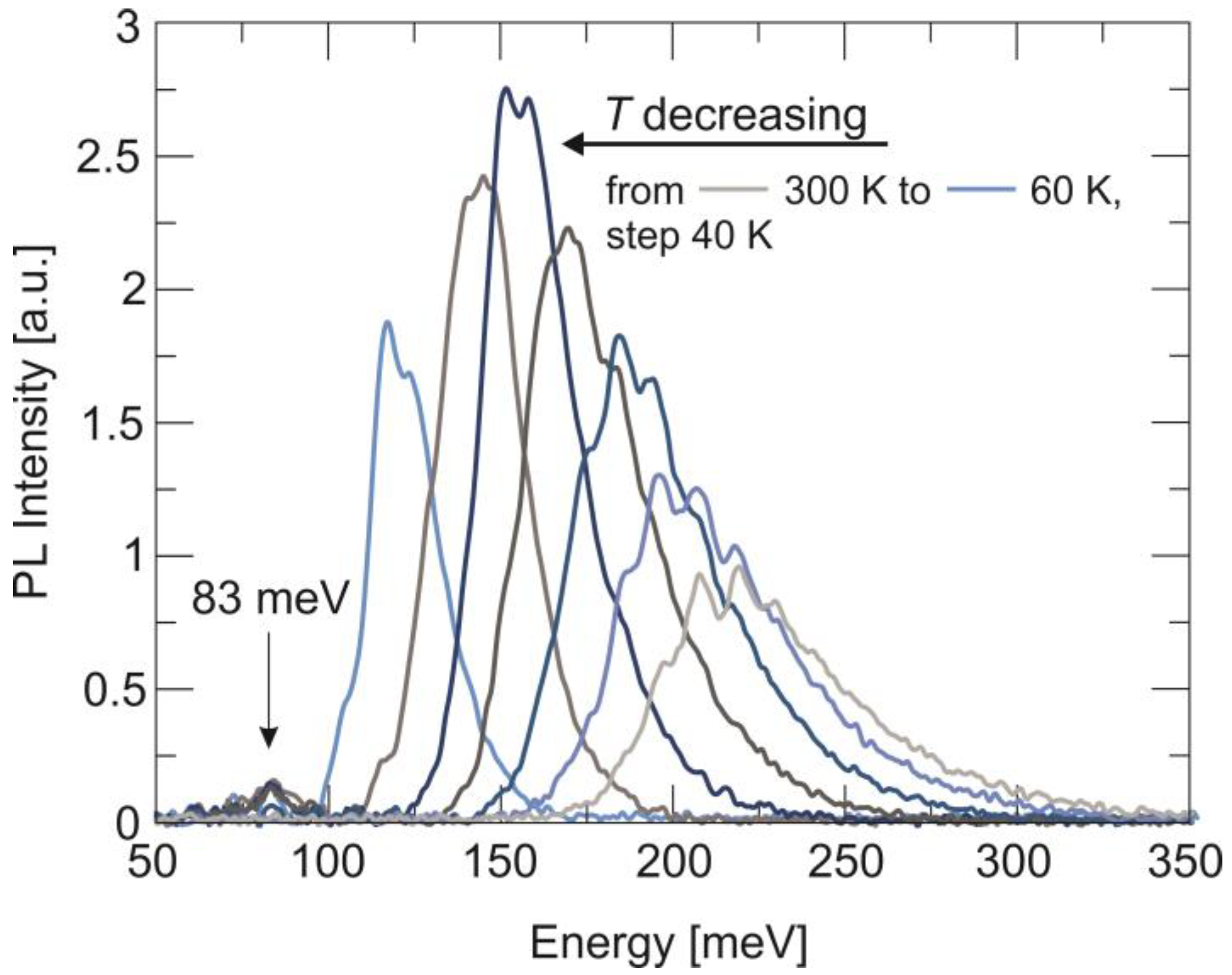

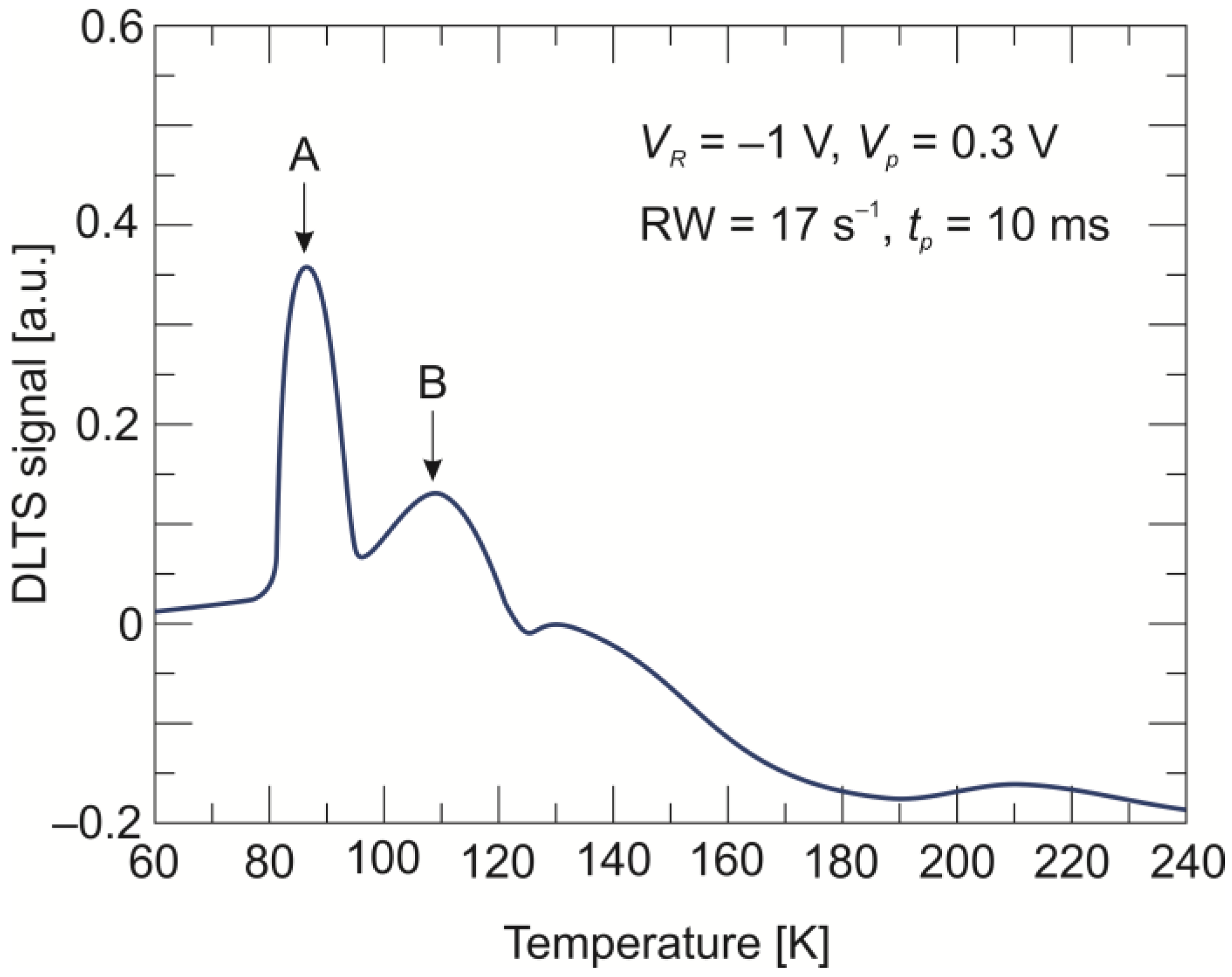

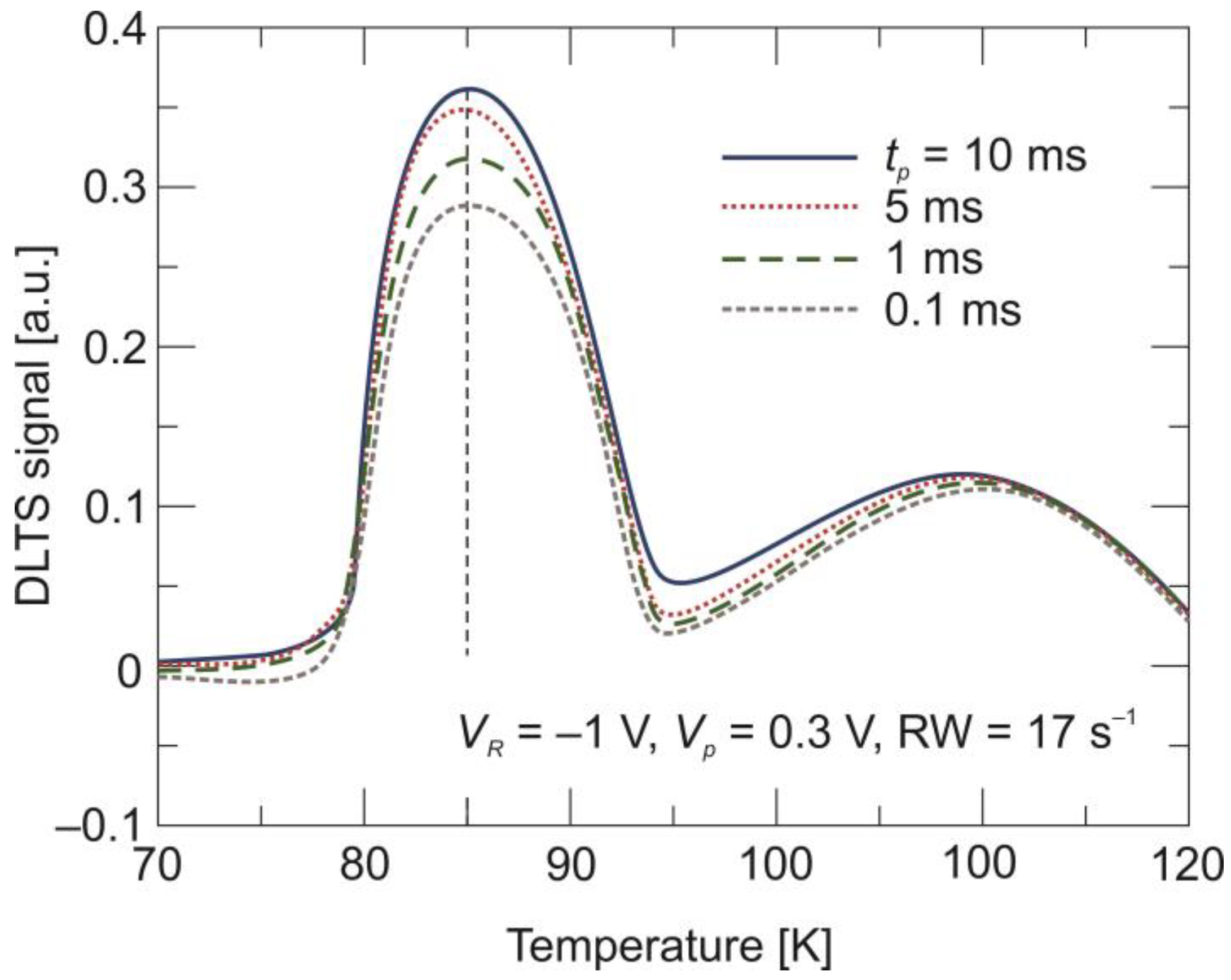

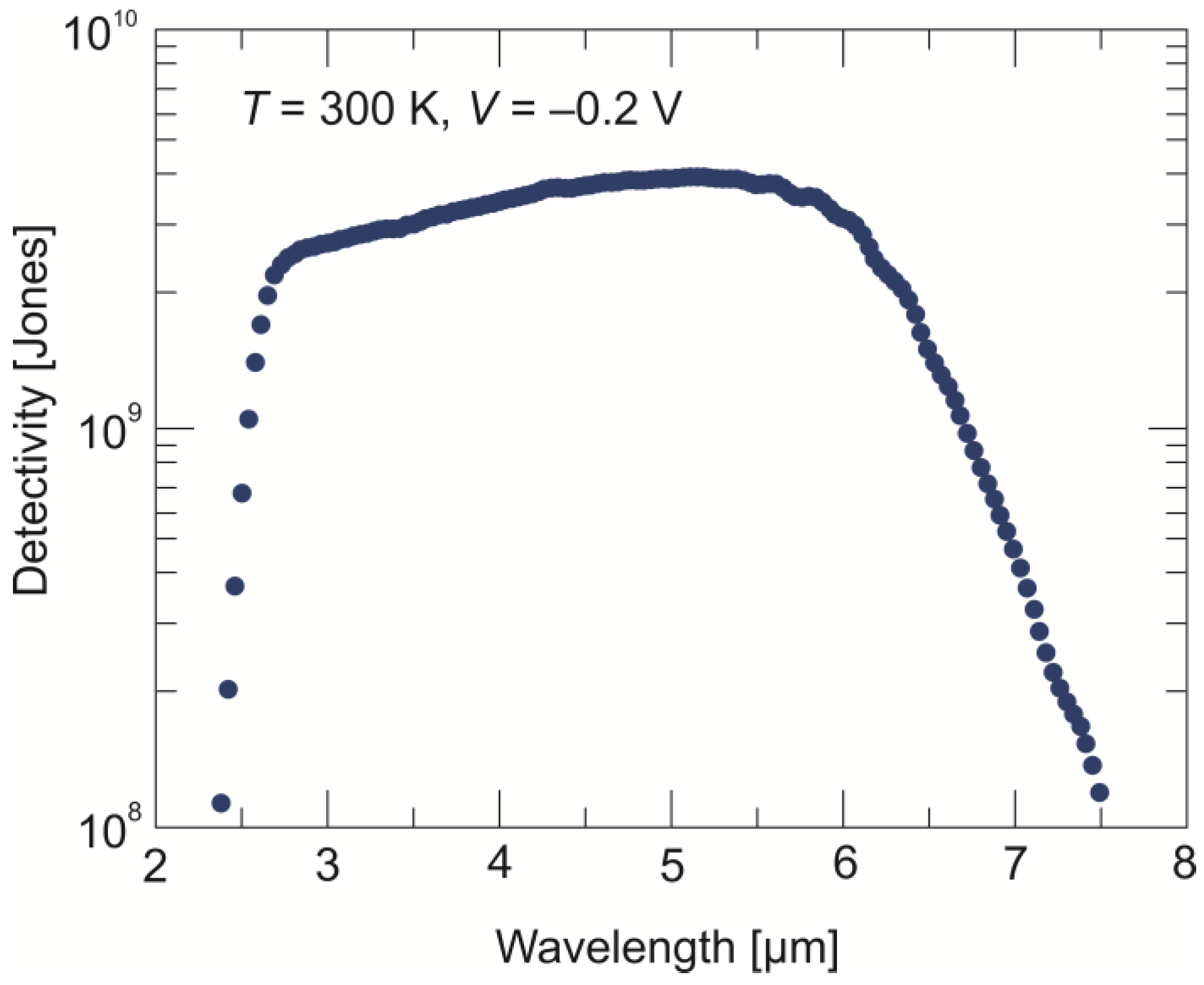

3. Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Piotrowski, J.; Rogalski, A. High-Operating-Temperature Infrared Photodetectors; SPIE Press: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowski, J.; Galus, W.; Grudzien, M. Near room-temperature IR photodetectors. Infrared Phys. 1991, 31, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawron, W.; Piotrowski, J.; Djuric, Z.G. New generation of near-room-temperature photodetectors. Opt. Eng. 1994, 33, 1413–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowski, J.; Rogalski, A. Uncooled long wavelength infrared photon detectors. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2004, 46, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinch, M.A. State-of-the-Art Infrared Detector Technology; SPIE Press: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ashley, T.; Elliott, C. Nonequilibrium devices for infra-red detection. Electron. Lett. 1985, 21, 451–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, T.; Elliott, C.T.; White, A.M. Infra-Red Detection Using Minority Carrier Exclusion. In Recent Developments in Materials & Detectors for the Infrared; SPIE Press: Bellingham, WA, USA, 1986; pp. 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- White, A. Auger suppression and negative resistance in low gap PIN diode structures. Infrared Phys. 1986, 26, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniewski, J.; Orman, Z.; Piotrowski, J.; Sioma, M.; Ornoch, L.; Romanis, M. Epitaxial in As Detectors Optically Immersed to GaAs Microlenses. In Infrared Technology and Applications XXVII; SPIE Press: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2001; pp. 721–729. [Google Scholar]

- Martyniuk, P.; Gawron, W.; Madejczyk, P.; Rogalski, A.; Piotrowski, J. Modeling of HgCdTe LWIR detector for high operation temperature conditions. Metrol. Meas. Syst. 2013, 20, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Xu, L.; Tang, W.; Zhang, S. Auger-suppression in barrier-blocking HgCdTe long-wavelength infrared detector. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2023, 134, 104918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madejczyk, P.; Gawron, W.; Martyniuk, P.; Keblowski, A.; Pusz, W.; Pawluczyk, J.; Kopytko, M.; Rutkowski, J.; Rogalski, A.; Piotrowski, J. Engineering steps for optimizing high temperature LWIR HgCdTe photodiodes. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2017, 81, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achtenberg, K.; Gawron, W.; Bielecki, Z. Low-frequency noise and impedance measurements in Auger suppressed LWIR N+p(π)P+n+ HgCdTe detector. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2024, 137, 105110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopytko, M.; Kębłowski, A.; Gawron, W.; Pusz, W. LWIR HgCdTe barrier photodiode with Auger-suppression. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2016, 31, 035025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyniuk, P.; Gawron, W.; Stępień, D.; Pawluczyk, J.; Kębłowski, A.; Madejczyk, P.; Kopytko, M.; Koźniewski, A. Status of long-wave Auger suppressed HgCdTe detectors operating >200 K. Opto Electron. Rev. 2015, 23, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyniuk, P.; Madejczyk, P.; Kopytko, M.; Gawron, W.; Rutkowski, J. Utmost response time of long-wave HgCdTe photode-tectors operating under zero voltage condition. Opt. Quant. Electron. 2018, 50, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emelie, P.Y.; Velicu, S.; Grein, C.H.; Phillips, J.D.; Wijewarnasuriya, P.S.; Dhar, N.K. Modeling of LWIR HgCdTe Au-ger-Suppressed Infrared Photodiodes under Nonequilibrium Operation. J. Electron. Mater. 2008, 37, 1362–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itsuno, A.M.; Emelie, P.Y.; Phillips, J.D.; Velicu, S.; Grein, C.H.; Wijewarnasuriya, P.S. Arsenic Diffusion Study in HgCdTe for Low p-Type Doping in Auger-Suppressed Photodiodes. J. Electron. Mater. 2010, 39, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Carmody, M.; Piquette, E.; Dreiske, P.; Chen, A.; Yulius, A.; Edwall, D.; Bhargava, S.; Zandian, M.; Tennant, W.E. High-Operating Temperature HgCdTe: A Vision for the Near Future. J. Electron. Mater. 2016, 45, 4587–4595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Dreiske, P.; Ellsworth, J.; Cottier, R.; Chen, A.; Tallaricao, S.; Yulius, A.; Carmody, M.; Piquetteb, E.; Zandian, M.; et al. Law 19—The Ultimate Photodiode Performance Metric. In Infrared Technology and Applications XLVI; SPIE Press: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tunnicliffe, J.; Irvine, S.; Dosser, O.; Mullin, J. A new MOVPE technique for the growth of highly uniform CMT. J. Cryst. Growth 1984, 68, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svoronos, S.A.; Woo, W.W.; Irvine, S.J.C.; Sankur, H.O.; Bajaj, J. A model of the interdiffused multilayer process. J. Electron. Mater. 1996, 25, 1561–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxey, C.D.; Capper, P.; Baker, I.M. MOVPE Growth of Cadmium Mercury Telluride and Applications. In Metalorganic Vapor Phase Epitaxy (MOVPE): Growth, Materials Properties and Applications; Irvine, S., Capper, P., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 293–324. [Google Scholar]

- Gawron, W.; Sobieski, J.; Manyk, T.; Kopytko, M.; Madejczyk, P.; Rutkowski, J. MOCVD Grown HgCdTe Heterostructures for Medium Wave Infrared Detectors. Coatings 2021, 11, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

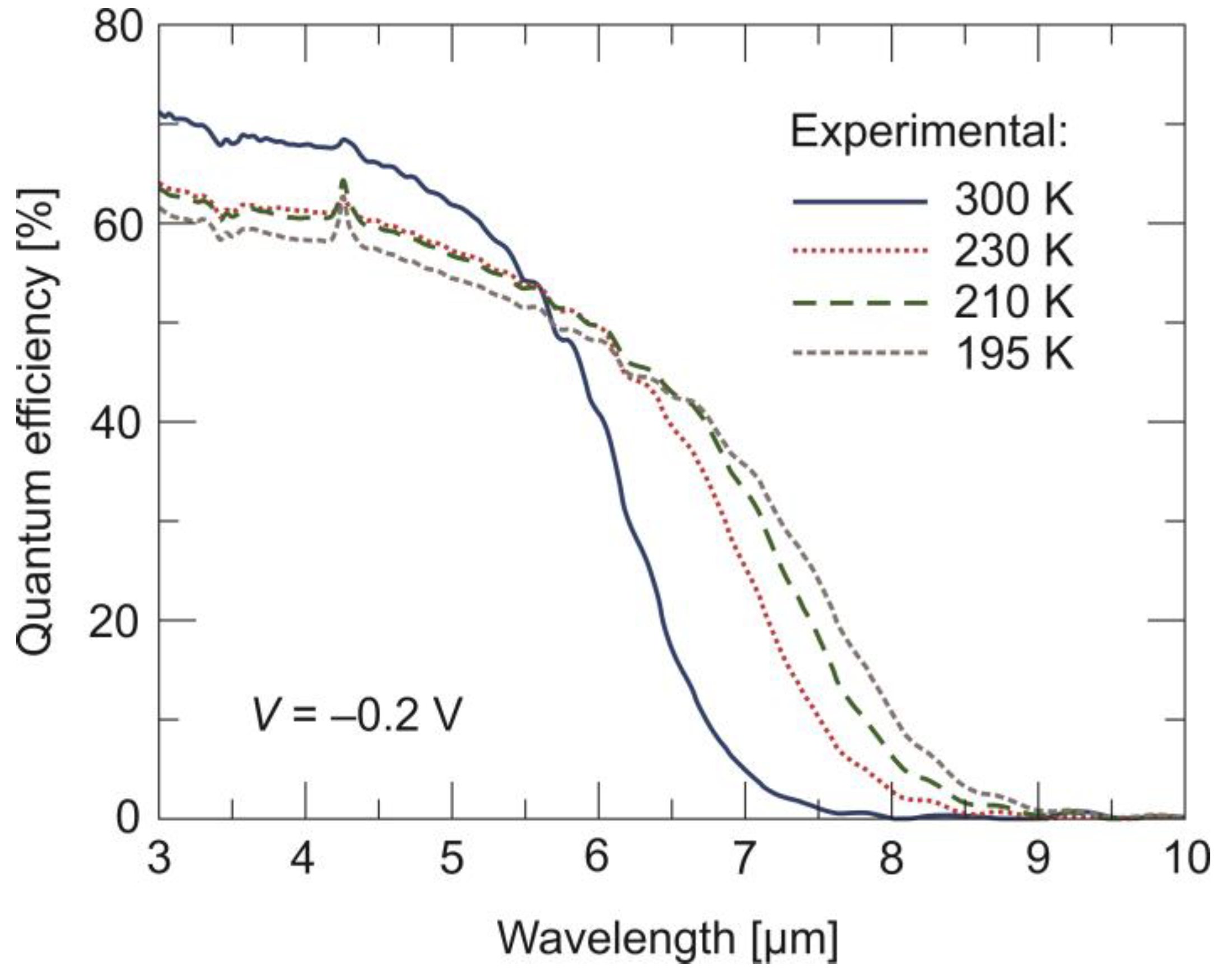

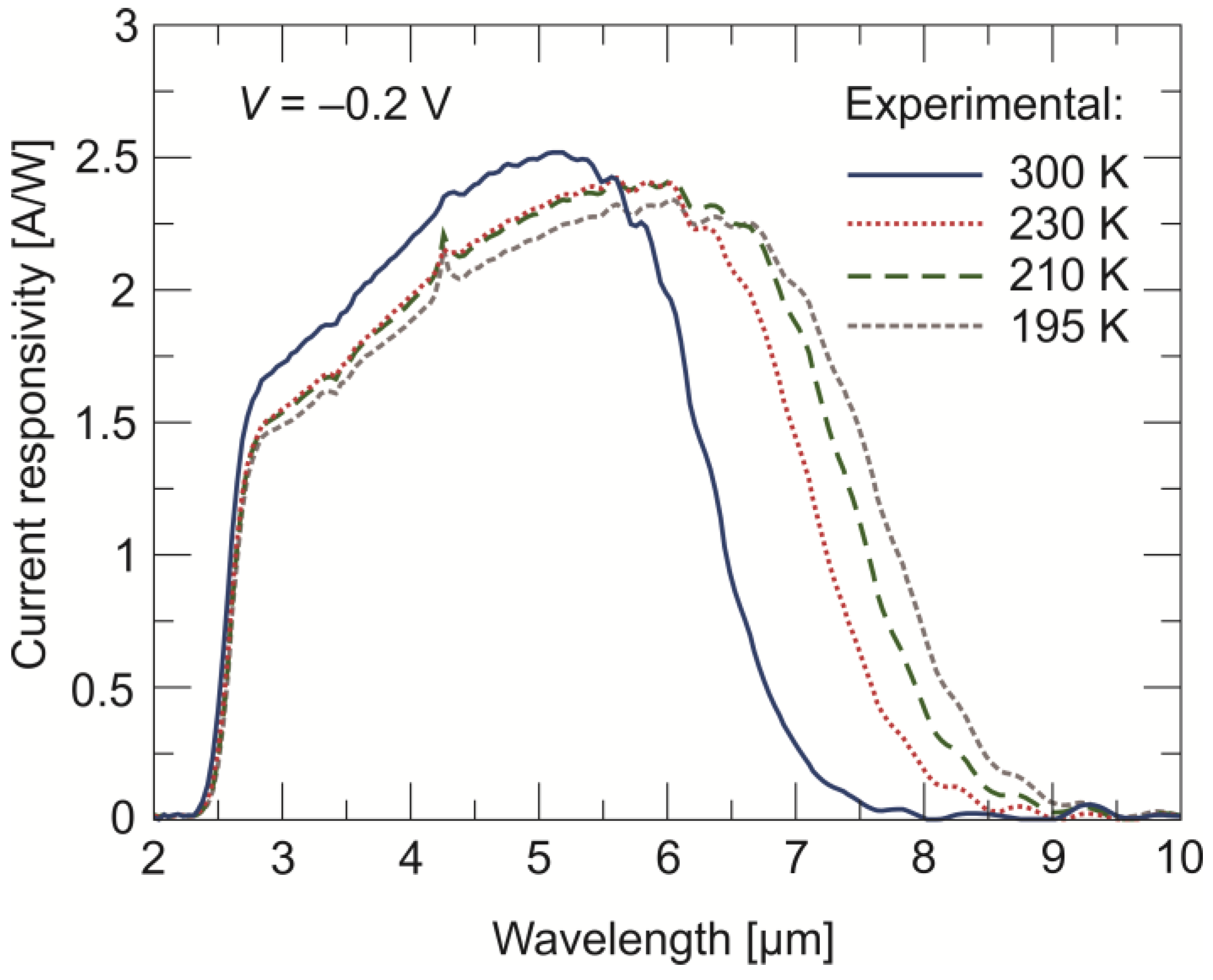

- Hansen, G.L.; Schmit, J.L.; Casselman, T.N. Energy gap versus alloy composition and temperature in Hg 1-xCdxTe. J. Appl. Phys. 1982, 53, 7099–7101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, F.-Y.; Ma, S.-Y.; Hong, J.; Yang, P.-X.; Jing, C.-B.; Chen, Y.; Chu, J.-H. Optical characterization of defects in narrow-gap HgCdTe for infrared detector applications. Chin. Phys. B 2019, 28, 17104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

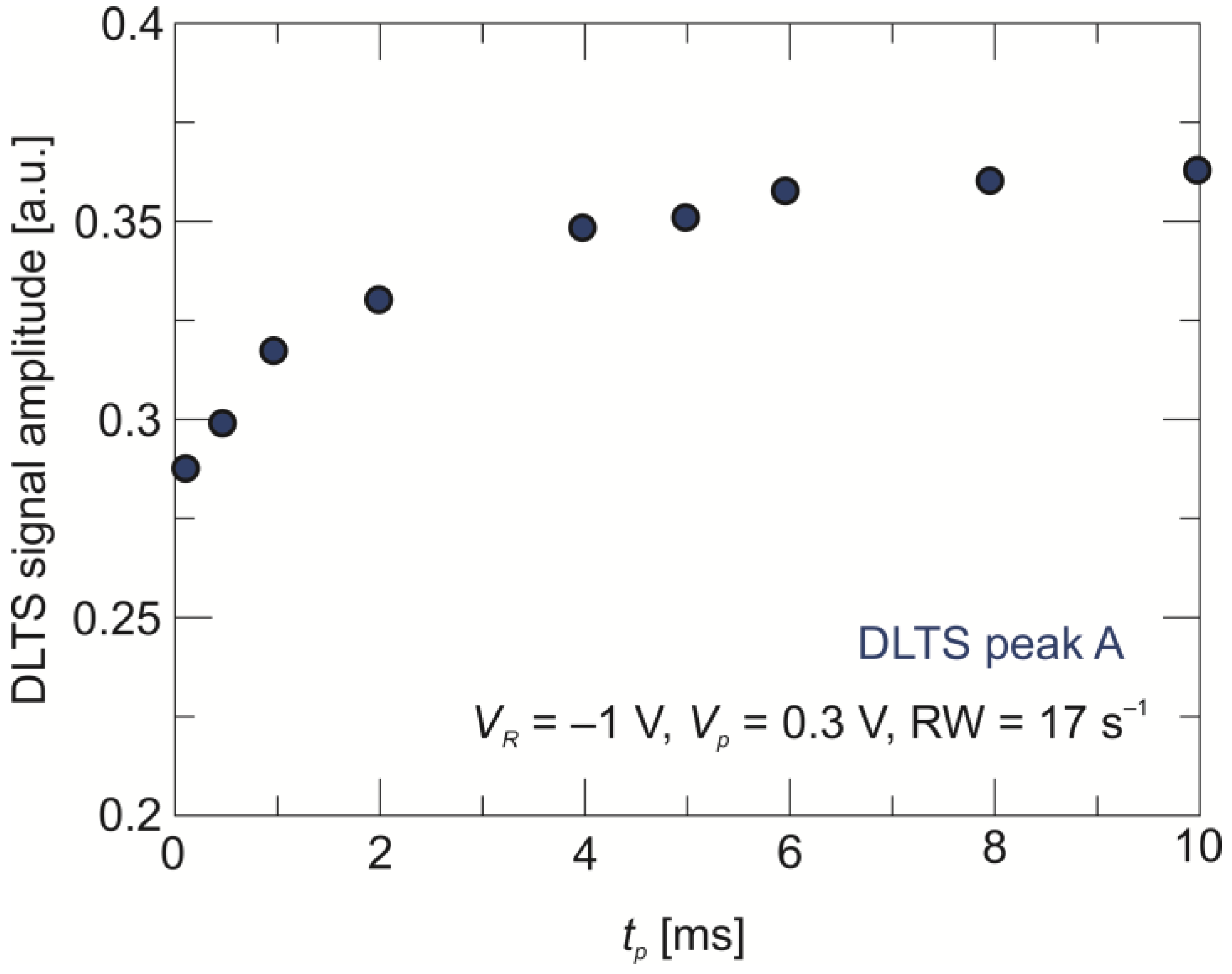

- Majkowycz, K.; Murawski, K.; Manyk, T.; Rutkowski, J.; Kopytko, M.; Martyniuk, P. DLTS Study of Defects in HgCdTe Heter-ostructure Photodiode. J. Electron. Mater. 2023, 52, 7074–7080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majkowycz, K.; Kopytko, M.; Murawski, K.; Martyniuk, P. The method for extracting defect levels in the MCT multilayer low bandgap heterostructures. Opto Electron. Rev. 2023, 32, 149182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polla, D.L.; Aggarwal, R.L.; Mroczkowski, J.A.; Shanley, J.F.; Reine, M.B. Observation of deep levels in Hg1-xCdxTe with optical modulation spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1982, 40, 338–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.H.; Rujirawat, S.; Ashokan, R.; Grein, C.H.; Sivananthan, S. Ionization energy of acceptors in As-doped HgCdTe grown by molecular beam epitaxy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1998, 73, 638–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.E.; James, K.; Merz, J.; Braunstein, R.; Burd, M.; Eetemadi, M.; Hutton, S.; Drumheller, J. Status of point defects in HgCdTe. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 1985, 3, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selamet, Y.; Grein, C.H.; Lee, T.S.; Sivananthan, S.; Lange, M.D.; Monfroy, G.; Faurie, J.P.; Debnath, M.C.; Mishima, T.D.; Santos, M.B.; et al. Electrical properties of in situ As doped Hg1−xCdxTe epilayers grown by molecular beam epitaxy. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B Microelectron. Nanometer Struct. 2001, 19, 1488–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majkowycz, K.; Murawski, K.; Kopytko, M. New insight into defect energy levels in HgCdTe. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2024, 137, 105126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogalski, A. Infrared and Terahertz Detectors, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

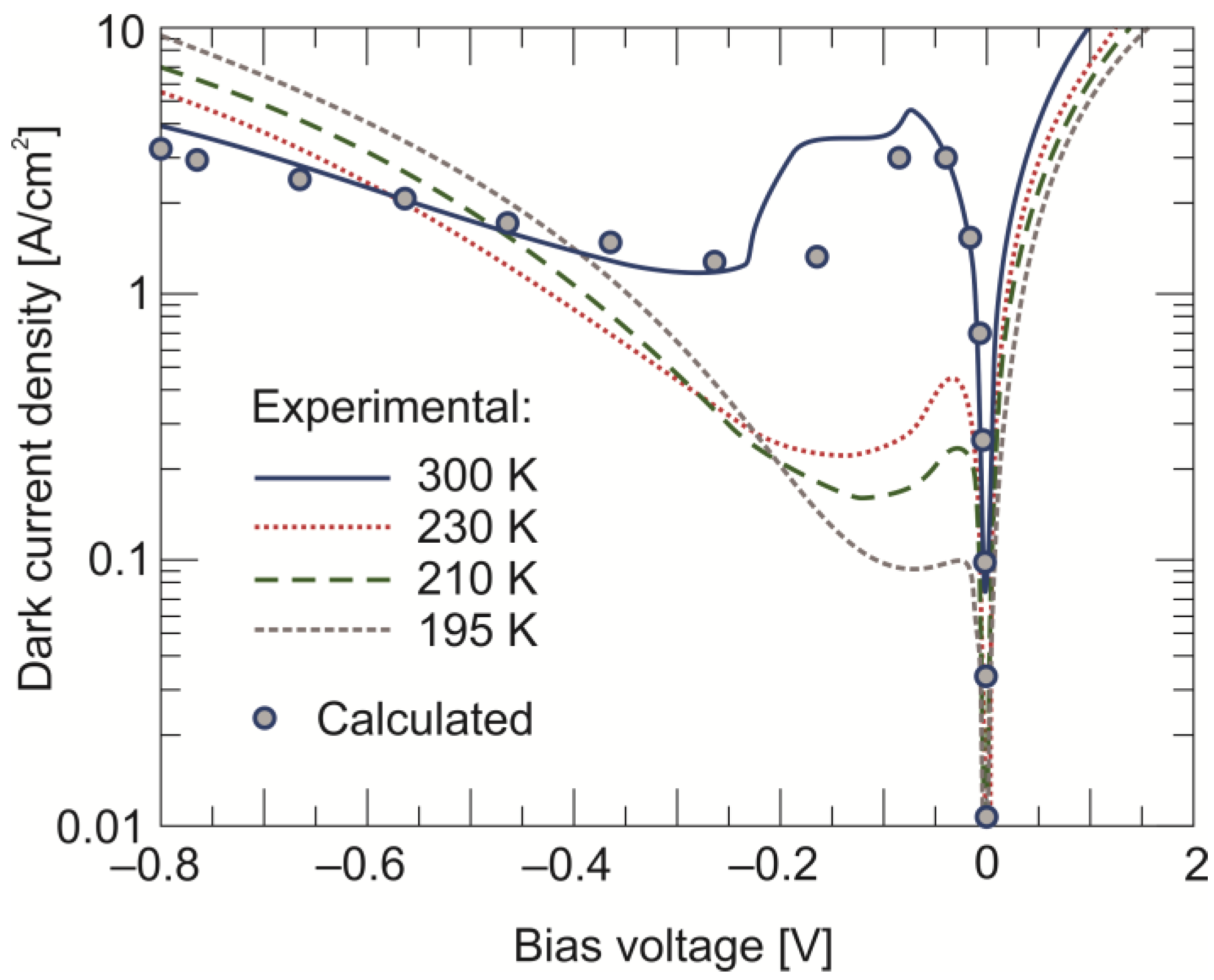

| Parameter | Determined | Assumed |

|---|---|---|

| Defect identification | VHg | |

| Activation energy, ET – EV [meV] | 83 (PL) | 86 |

| 89 (DLTS) | ||

| Trap concentration, NT [cm−3] | 3 × 1014 | 3.4 × 1014 |

| Hole capture cross-section, σp [cm2] | 4 × 10−15 | 1 × 10−16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kopytko, M.; Majkowycz, K.; Murawski, K.; Sobieski, J.; Gawron, W.; Martyniuk, P. Defect Analysis in a Long-Wave Infrared HgCdTe Auger-Suppressed Photodiode. Sensors 2024, 24, 3566. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113566

Kopytko M, Majkowycz K, Murawski K, Sobieski J, Gawron W, Martyniuk P. Defect Analysis in a Long-Wave Infrared HgCdTe Auger-Suppressed Photodiode. Sensors. 2024; 24(11):3566. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113566

Chicago/Turabian StyleKopytko, Małgorzata, Kinga Majkowycz, Krzysztof Murawski, Jan Sobieski, Waldemar Gawron, and Piotr Martyniuk. 2024. "Defect Analysis in a Long-Wave Infrared HgCdTe Auger-Suppressed Photodiode" Sensors 24, no. 11: 3566. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113566

APA StyleKopytko, M., Majkowycz, K., Murawski, K., Sobieski, J., Gawron, W., & Martyniuk, P. (2024). Defect Analysis in a Long-Wave Infrared HgCdTe Auger-Suppressed Photodiode. Sensors, 24(11), 3566. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113566