Abstract

In view of the difficulties regarding that airborne navigation equipment relies on imports and the expensive domestic high-precision navigation equipment in the manufacturing field of Chinese navigable aircraft, a dual-antenna GNSS (global navigation satellite system)/MINS (micro-inertial navigation system) integrated navigation system was developed to implement high-precision and high-reliability airborne integrated navigation equipment. First, the state equation and measurement equation of the system were established based on the classical discrete Kalman filter principle. Second, according to the characteristics of the MEMS (micro-electric-mechanical system), the IMU (inertial measurement unit) is not sensitive to Earth rotation to realize self-alignment; the magnetometer, accelerometer and dual-antenna GNSS are utilized for reliable attitude initial alignment. Finally, flight status identification was implemented by the different satellite data, accelerometer and gyroscope parameters of the aircraft in different states. The test results shown that the RMS (root mean square) of the pitch angle and roll angle error of the testing system are less than 0.05° and the heading angle error RMS is less than 0.15° under the indoor static condition. A UAV flight test was carried out to test the navigation effect of the equipment upon aircraft take-off, climbing, turning, cruising and other states, and to verify the effectiveness of the system algorithm.

1. Introduction

Integrated navigation system research is a hot spot in the fields of aviation and aerospace [1]. At present, the most widely used integrated navigation method in the aviation field is the integration of GNSS (global navigation satellite system) and INS (inertial navigation system) [2,3]. GNSS is a system capable of global positioning and time synchronization. It can provide continuous, full-time, high-precision localization services. It has now been widely used in military, aviation, navigation, automobile, agriculture, consumer electronics and numerous other fields and has become an indispensable and significant navigation mode in people’s daily lives [4]. For integration of GNSS and INS, currently, the commonly used classification standard is divided into loose integration, tight integration and deep integration according to different coupling degrees [5,6]. In the relaxed joint system, the GNSS and INS work independently and the GNSS output navigation results are then used to filter and correct the INS solution results [7]. This approach has the advantages of small system computation, high real-time performance, easy engineering implementation and high product reliability. Currently, most integrated navigation products on the market use a loose combination scheme. A loose combination, however, has its flaws. When GNSS can receive less than four satellite signals, satellite positioning fails and the loose combination does not function properly at this time. Therefore, other sensors are needed to ensure short-term navigation accuracy of the system. Currently, many loosely integrated navigation products have been applied in practical projects in China. Among them, loosely integrated navigation products are mostly used in military weapons and equipment, such as various missiles, Long March launch vehicles and aircraft. Xi’an Precision Measurement and Control has accumulated a great deal of technology in loosely integrated products and has successively launched several low-cost GNSS/INS integrated navigation systems, which have been widely used in vehicle navigation.

At present, the integrated navigation equipment widely used in the fields of military, commercial aircraft and shipping in China is mostly based on the products of laser gyro and fiber optic gyro. The equipment presents high precision and reliability priorities, while its price is also extremely expensive. However, due to the low cost of navigable aircraft and sensitivity to the price of airborne equipment, it is not possible to use expensive fiber optic or laser gyro integrated navigation equipment, which causes most domestic navigable aircraft manufacturers to rely on imported integrated navigation equipment based on MEMS (micro-electric-mechanical system) gyro and accelerometer. Navigation devices based on MEMS devices are tiny, light-weight, low-power consumption, low-cost and convenient in later maintenance. In addition, with in-depth research of MEMS-related technologies in countries around the world in recent years, accuracy and reliability of navigation devices based on MEMS have been considerably improved [8] and their performance could meet the requirements of integrated navigation devices for navigable aircraft. However, there is still a gap in popularity and reliability compared to foreign products [9,10].

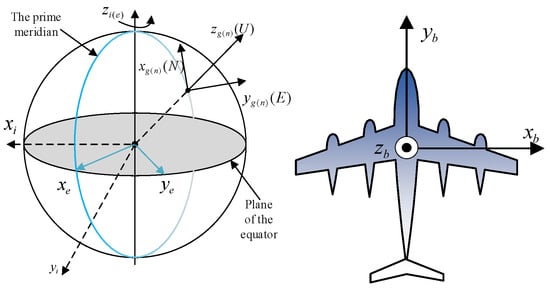

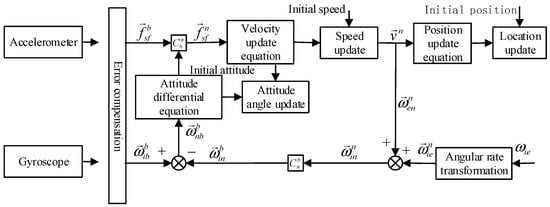

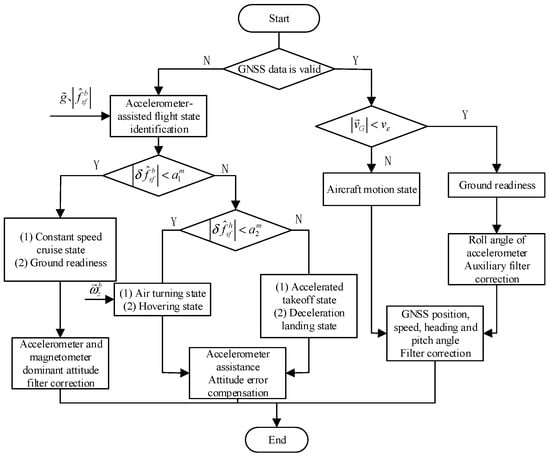

In this paper, we describe the details of the mathematical model and algorithm design of the dual-antenna GNSS/MINS integrated navigation system. First, the coordinate system commonly used in navigation systems is described and the Euler angle representation method and variation range of vehicular attitude are explained. Then, the mathematical model of the dual-antenna integrated navigation system is proposed, and the core algorithms of attitude, velocity and position update are analyzed and the error equation is derived. After that, the initial attitude alignment via accelerometer and magnetometer and pitch and heading angle alignment using dual-antenna GNSS are studied. Moreover, in the case of satellite failure, the flight state of the aircraft is judged by accelerometer and gyroscope measurements, and then the attitude angle is corrected by the accelerometer in the low dynamic flight state of the aircraft.

5. Experimental Verification and Analysis

To validate the actual performance as well as the reliability of this integrated navigation system, in this chapter, we detail an indoor static accuracy test of the equipment and UAV flight test to check the performance of the system under different environments and to verify the correctness of the system model and the feasibility of the system scheme.

5.1. Carry Out Indoor Static Experiment

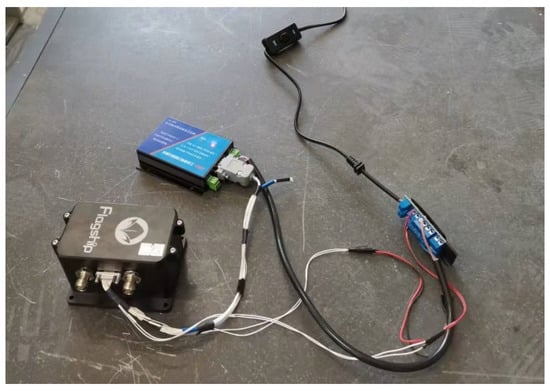

The first test is to test the static performance parameters of the system in an indoor environment. The main components of the indoor static experiment are an integrated navigation device body and a data recorder. The device was placed on a marble table in the laboratory, the power was started and, after the initialization of the device was completed, data were sent to the serial data logger and 30 min data were collected. Figure 4 shows the field experiment for static testing.

Figure 4.

Field experiment diagram of static test.

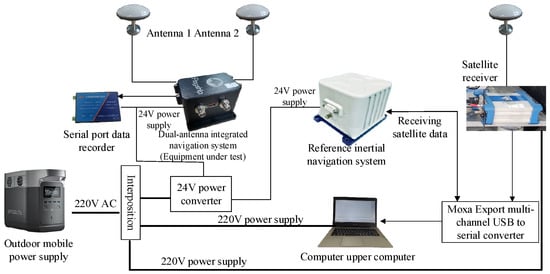

The experimental system installation diagram is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Installation diagram of experimental system.

The entire system is powered by an outdoor mobile 220 V AC supply. The tested dual-antenna GNSS/MINS integrated navigation system, reference fiber inertial navigation system and serial port data recorder use 24 V DC power supply provided by an AC/DC power adapter, while the laptop and reference satellite receiver use 220 V AC power supply.

The tested integrated navigation system receives satellite data through two satellite antennas and sends the final navigation solution data to a serial port data recorder for storage. The distance between the two satellite antennas is 1.5 m. The reference inertial navigation device reads the satellite data sent by the satellite receiver through a Moxa Upload multi-channel serial port USB to serial port converter and performs an integrated navigation solution that then sends the navigation data through the converter to the uplink computer for saving.

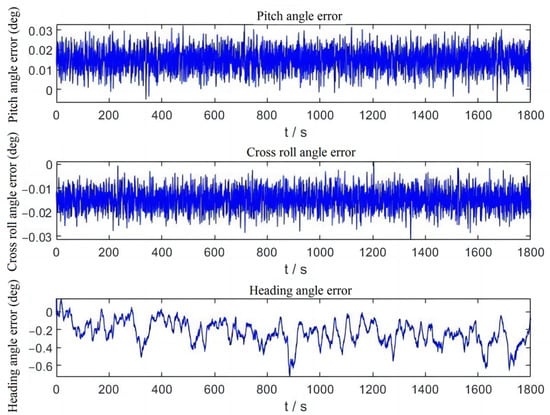

The test results are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Static test attitude error output result graph.

In the indoor static test situation, the system first detects that the satellite signal is not available, so it performs flight status identification by accelerometer and determines that the current device is in ground-ready state. During the ground-ready state without satellite signal, the system will use an accelerometer to correct the traverse and pitch angles of the attitude and a magnetometer to correct the heading angle. From the results in Table 2, the errors of pitch and roll angles in static condition are extremely small, and the RMS is within 0.75°. The error of heading angle is larger than the pitch and roll angles corrected by accelerometer due to fusion correction by magnetometer, but the error RMS is also within 1°.

Table 2.

Static test attitude angle error.

5.2. Conduct UAV Flight Test

This flight test will carry the system inside the aircraft near the propeller using the on-board 28 V DC to power the test equipment, using the on-board 12 V battery to power the industrial serial data logger, the reference equipment is the on-board main fiber optic inertial guidance and the GPS signal and heading are provided by the aircraft. Since the aircraft does not provide velocity information, the system will not perform velocity measurement update and comparison in this subsection. The flight process is divided into several phases, such as pre-takeoff preparation, takeoff, turn, cruise and landing, etc. This flight test will focus on analyzing the data of the first 2190 s, which contain the additional four phases of the flight process except for landing.

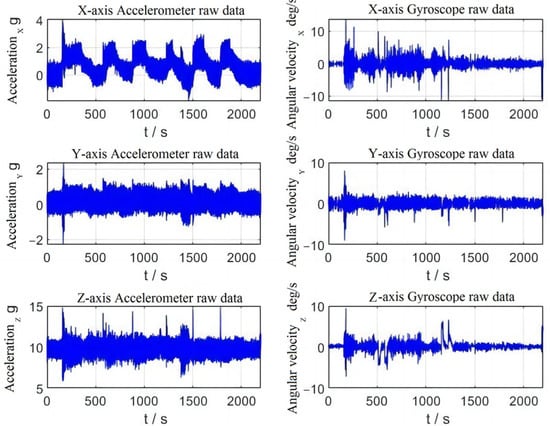

From Figure 7, it can be demonstrated that the aircraft will have an overall large amount of noise due to the vibration of the propeller. Even when the aircraft is in the ground preparation phase between 0 and 190 s, the gyroscope and accelerometer have a large amount of noise, but it can be considered as zero-mean noise, which has minor effect on later data solving. Compared with the sports car test, when the aircraft in the flight test undergoes dynamic changes, the amount of data change of its accelerometer and gyroscope is relatively small, the dynamic impact is smaller and the navigation effect can be expected to be better.

Figure 7.

Flight test accelerometer and gyroscope data.

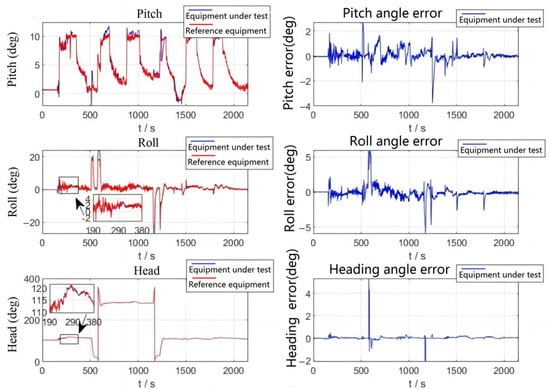

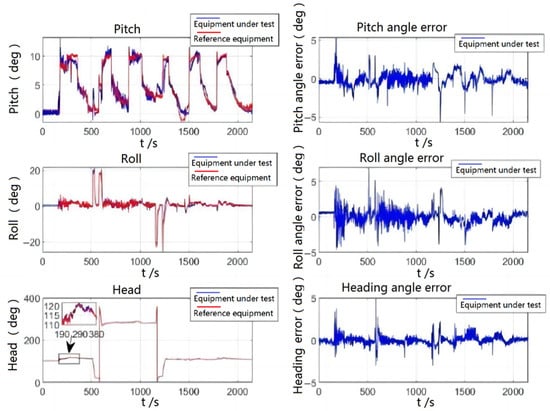

As shown in Figure 8, the aircraft is in the ground preparation state during 0–190 s, and the errors of the three attitude angles are relatively small. During the period of 191–380 s, the aircraft is in the takeoff phase, at which point the aircraft raises its head and the error of the pitch angle increases but remains within the range of 2°. The error of the cross-roll angle also has some fluctuations and remains within 1.5 degrees overall, and the error of the heading angle is small. During the period of 500–610 s, the aircraft starts the first large-angle turn, which leads to an increase in error, and the error exceeds 2°. During 500–610 s, the aircraft starts to make the first large-angle turn because there is no correction for the cross-roll angle at this time, which leads to an increase in error and further a brief large error fluctuation in the pitch angle; the error was more than 2°; this error was quickly corrected. Heading angle due to focus on stability, resulting in a slightly slower following velocity, causes large error, about 4°; about 1–2 s later, the system followed on the true heading angle and the amount of error returned to normal. After that, the aircraft made five climbs and one large maneuvering turn, during which the attitude angle error would increase, but the maximum error was within 5° and the correction velocity was fast.

Figure 8.

Flight test attitude comparison and attitude error.

The following table shows the quantitative analysis of the flight test attitude angle errors. In Table 3, the heading angle error is the smallest and the cross-roll angle error is a bit larger than the pitch angle error, but the root mean square of the error is within the allowable range of the index.

Table 3.

Flight test attitude error.

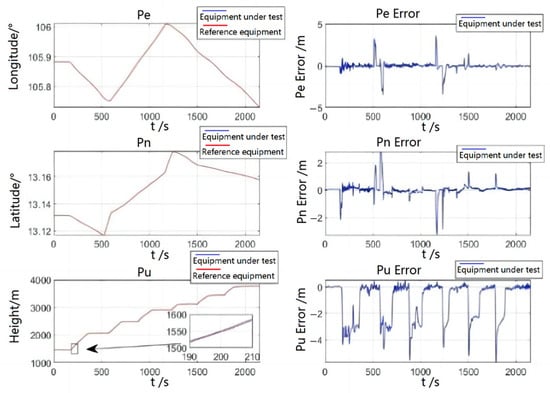

In Figure 9, the error in longitude and latitude of the system is relatively small, and a slightly larger amount of error will be generated during the takeoff, climb and turn phases. Regarding altitude, because the system depends on the correction of the satellite, there is a certain delay in the satellite signal, which will produce slightly larger error in the climb phase, about 4 m. Although the altitude error will be reduced if the measurement noise of the altitude is reduced at this time, the northward and skyward position error will increase, so a compromise is needed. When the aircraft is flying smoothly, the altitude error can be corrected quickly.

Figure 9.

Flight test position comparison and error.

The following table shows the quantitative analysis of the position error of the flight test. From Table 4, the root MSE of the position in the east direction and north direction are around 0.45 m, and the root MSE in the sky direction is larger, which can also meet the requirement of less than 1.5 m.

Table 4.

Flight test position error.

The system’s attitude solving effect in the absence of satellite is verified. After the 30S initial alignment of the system, the GNSS signal of the system is disconnected so that the system only uses the raw IMU data for attitude and heading angle solution and filtering, and the experimental effect is shown in Figure 10. When there is no GNSS signal, the system will use IMU data for flight attitude discrimination and then use accelerometer for attitude angle correction in the low acceleration phase of flight. From Figure 8, the attitude angle solution using accelerometer will have a larger amount of error compared with the attitude acquired by GNSS, but the systematic error RMS is guaranteed to be within 1 degree, which can be used as an inertial guide to provide higher accuracy attitude navigation information when there is no satellite signal from the aircraft.

Figure 10.

Inertial guidance attitude error.

Quantitative analysis of the attitude error is shown in Table 5. Through flight test verification, the effectiveness of the algorithm designed in this paper, using the angle, velocity and position information provided by GNSS and MEMS inertial guidance system for high precision data fusion, when the satellite signal fails, the IMU data alone can also be used to obtain better attitude solution accuracy to ensure the flight safety of the aircraft.

Table 5.

Inertial guidance attitude error.

6. Conclusions

By studying the discrete Kalman filter algorithm, the state-space model of the system is established based on the system error equation in this study. The mathematical model of the integrated dual-antenna GNSS/MINS navigation system is established and the integrated inertial guidance algorithm of Jet-Link is designed. The system is also tested in indoor static tests and UAV flight experiments to verify the attitude performance of the system, especially when it meets the index requirements without satellite signals. The experiments verified that the attitude, velocity and position accuracy through the system during take-off, climbing and turning are elevated and the errors are within the index range. It is realized that the attitude accuracy and position accuracy of the system meet the system index requirements when a GNSS signal is available. When there is no GNSS signal correction, the accelerometer can also be used to obtain a better attitude solution to ensure safe return and landing of the aircraft under GNSS signal rejection environment.

Future research will investigate the method to maintain the accuracy of MEMS inertial guidance solution for a longer duration in the absence of a satellite signal. Combined with the current situation of poor satellite signal due to complex terrain and mountainous plateaus in China, an airborne tight integration navigation algorithm will be studied. Using the existing hardware equipment, a more efficient and feasible algorithm will be explored to realize an algorithm solution of superior accuracy using low-cost computing units.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, M.X. and L.G.; software, P.S.; validation, M.X. and P.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.X. and P.S.; writing—review and editing, L.G. and Z.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Project of Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Education Commission of China (No. KJZD-K202104701).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hong, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, H.; Hu, W.; Qin, G. A time-controllable Allan variance method for MEMS IMU. Ind. Robot. Int. J. 2013, 40, 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson, D.; Dowdle, J. Deeply integrated code tracking: Comparative performance analysis. In Proceedings of the International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of The Institute of Navigation, Portland, OR, USA, 9–12 September 2003; pp. 2553–2561. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Guan, L.; Xu, D. Odometer Velocity and Acceleration Estimation Based on Tracking Differentiator Filter for 3D-Reduced Inertial Sensor System. Sensors 2019, 19, 4501–4517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, W.; Sun, W.; Gao, Y.; Wu, J. Vehicular Phase-Based Precise Heading and Pitch Estimation Using a Low-Cost GNSS Receiver. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Ban, Y.; Zhang, T.; Liu, J. Research progress and prospects of GNSS/INS deep integration. Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin. 2016, 37, 2895–2908. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, D.; Lim, D.W.; Cho, S.L.; Lee, S.J. Unified approach to ultra-tightly-coupled GPS/INS integrated navigation system. IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. 2011, 26, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, Q.; Wang, X.Y. Design of GPS/MEMS-IMU loose coupling navigation system. Ship Electron. Eng. 2018, 38, 52–56+59. [Google Scholar]

- Ayazi, F. Multi-DOF inertial MEMS: From gaming to dead reckoning. In Proceedings of the Solid-State Sensors, Actuators & Microsystems Conference, Beijing, China, 5–9 June 2011; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 2805–2808. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.P.; Wang, X.L. MEMS-SINS/GNSS deep integrated navigation system based on vector tracking. Navig. Control. 2019, 6, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Feng, S.G. Development status of airborne INS/GNSS deep integrated navigation system. Opt. Optoelectron. Technol. 2021, 19, 88–96. [Google Scholar]

- SAE AS8013A; Minimum Performance Standard of the Magnetic (Gyro Stabilized Type) Heading Instrument. International Society of Automation Engineers Aerospace Standards: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2008; pp. 4–9.

- SAE AS396B; Inclinometer (Indicating Gyro Stabilized Type) (Gyro Horizon, Gyro Attitude Meter). International Society of Automation Engineers Aerospace Standards: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2008; pp. 2–8.

- RTCA DO-160E/EUROCAEED-14F; American Aeronautical Radio Technical Commission (RTCA). RTCA: Washinton, DC, USA, 2007; pp. 11–139.

- Lin, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xiong, J. Specific force integration algorithm with high accuracy for strapdown inertial navigation system. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2015, 42, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, R.; Cheng, Q.; Zhang, W. Comparison of direct and indirect filtering modes for UAV integrated navigation. J. Beijing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. 2020, 46, 2156–2167. [Google Scholar]

- Gaoge, H.; Wei, W.; Yong, M. A new direct filtering approach to INS/GNSS integration. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2018, 77, 755–764. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Ren, X.; Fritsche, M.; Wickert, J.; Schuh, H. Precise positioning with current multi-constellation Global Navigation Satellite Systems: GPS, GLONASS, Galileo and BeiDou. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santerre, R.; Geiger, A.; Banville, S. Geometry of GPS dilution of precision: Revisited. GPS Solut. 2017, 21, 1747–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, B. Quaternion-Based Control Architecture for Determining Controllability Maneuverability Limits. In Proceedings of the AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 13–16 August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Cheng, M.; Aboelmagd, N. Research on the improved method for dual foot-mounted Inertial/Magnetometer pedestrian positioning based on adaptive inequality constraints Kalman Filter algorithm. Measurement 2019, 135, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.; Su, L.; Chu, K. Sensor data fusion for attitude stabilization in a low cost Quadrotor system. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE 15th International Symposium on Consumer Electronics (ISCE), Singapore, 14–17 June 2011; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Wang, J.; Du, M. A Fast SINS Initial Alignment Method Based on RTS Forward and Backward Resolution. J. Sens. 2017, 2017, 7161858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.; Li, E.; Qin, H. A Performance Improvement Method for Low-Cost Land Vehicle GPS/MEMS-INS Attitude Determination. Sensors 2015, 15, 5722–5746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, L.; Sun, P.; Xu, X.; Zeng, J.; Rong, H.; Gao, Y. Low-cost MIMU based AMS of highly dynamic fixed-wing UAV by maneuvering acceleration compensation and AMCF. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2021, 117, 106975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).