FoGGAN: Generating Realistic Parkinson’s Disease Freezing of Gait Data Using GANs

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Related Works

3. Data Feature Selection and Generation Using GANs

3.1. Dataset

- 0: not part of the experiment. For instance, the sensors were installed on the user or the user was performing activities unrelated to the experimental protocol, such as debriefing;

- 1: experiment, no freeze (can be any of stand, walk, or turn);

- 2: freeze.

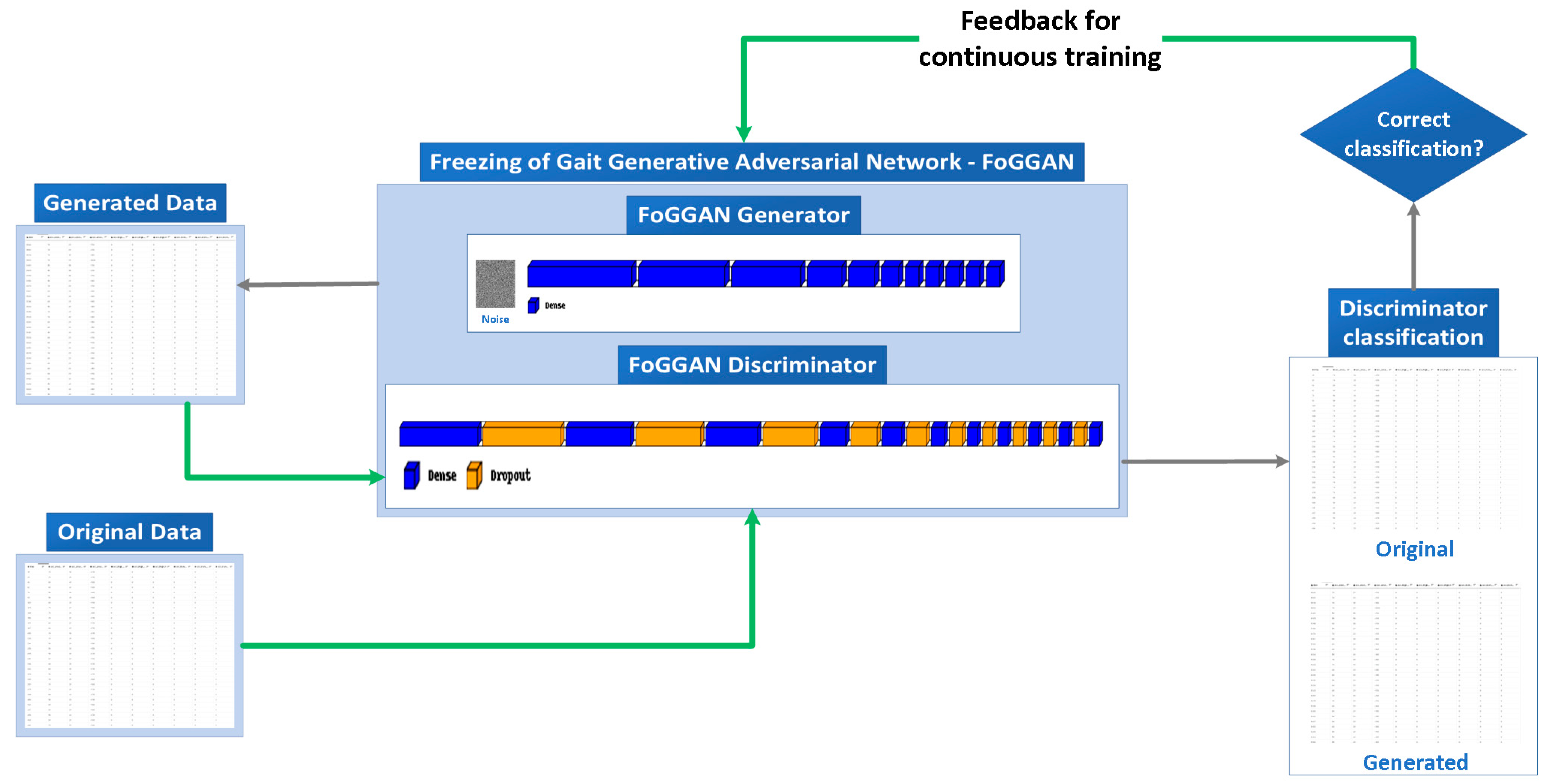

3.2. FoGGAN Architecture

4. Results

4.1. Comparison Results between Original and FoGGAN-Generated Data

- Heatmaps depicting correlation matrices offer a valuable solution in terms of visualizing clusters and detecting dissimilarities between the real and generated datasets. These heatmaps prove especially beneficial for pinpointing patterns of similarity scores linked to distinct data features.

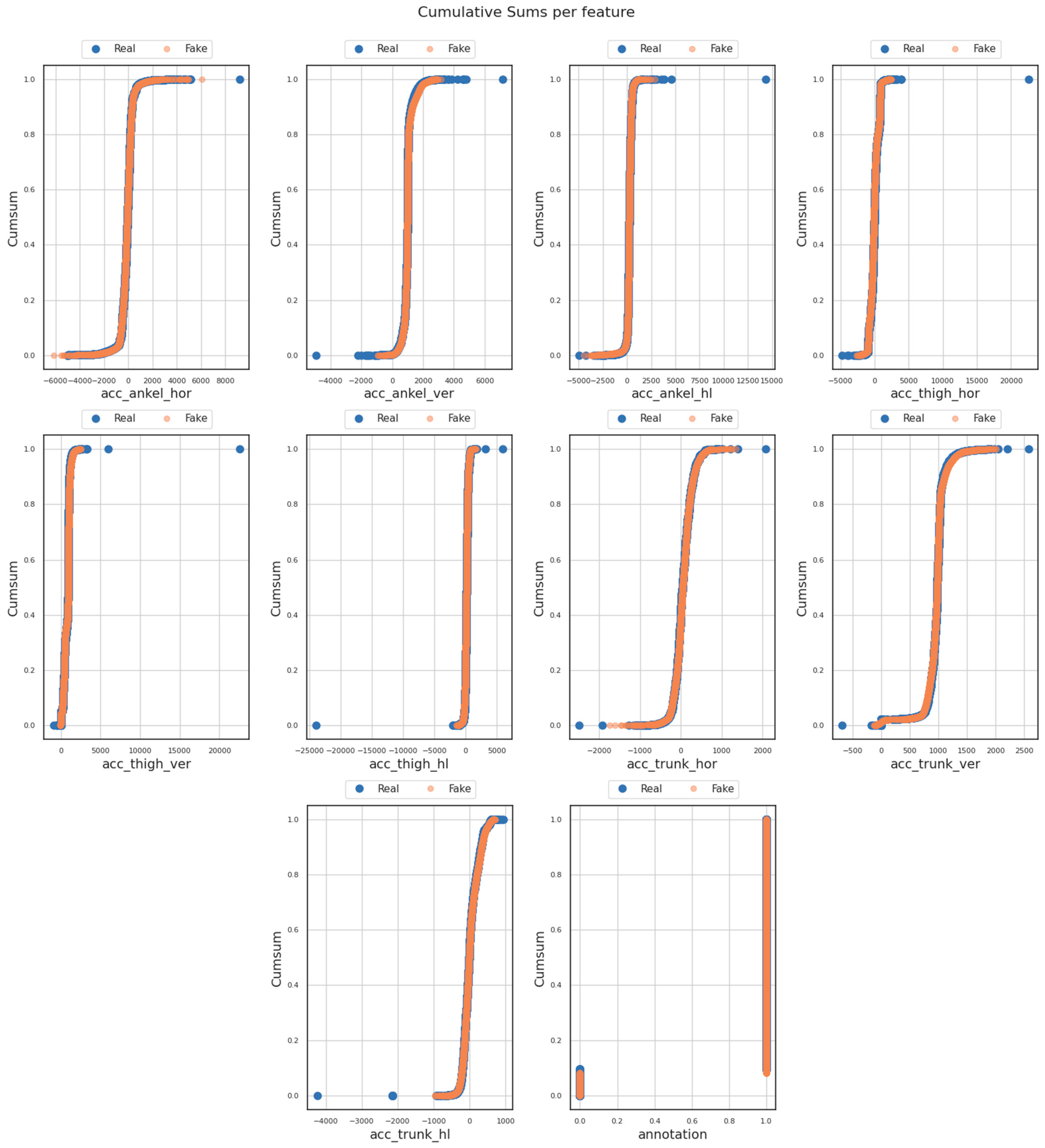

- Cumulative sum (or cumsum) diagrams provide a visual representation of the cumulative sum for both the real and generated datasets. In the context of assessing similarity scores and comparing datasets using the FoGGAN model, the cumsum diagram offered an effective way to visualize the accumulation of the similarity scores computed between the original and generated datasets gradually.

- Logarithmic (Log) mean and standard deviation (STD) diagrams usually serve as tools for comparing similarity scores between the original dataset and the one generated by a GAN (the ‘FoGGAN’ in our study). A Log mean diagram provided a visual representation of the average or mean similarity score between the original and generated dataset(s) for each training epoch. This depiction enabled an assessment of how the similarity score evolves over time, revealing whether the generated dataset’s similarity to the real dataset is increasing or decreasing during the training process. Conversely, a standard deviation diagram (STD) illustrated the variability in similarity scores between the real and generated datasets for each training epoch. This visualization assessed the consistency of the similarity score and identifies significant fluctuations in similarity between epochs.

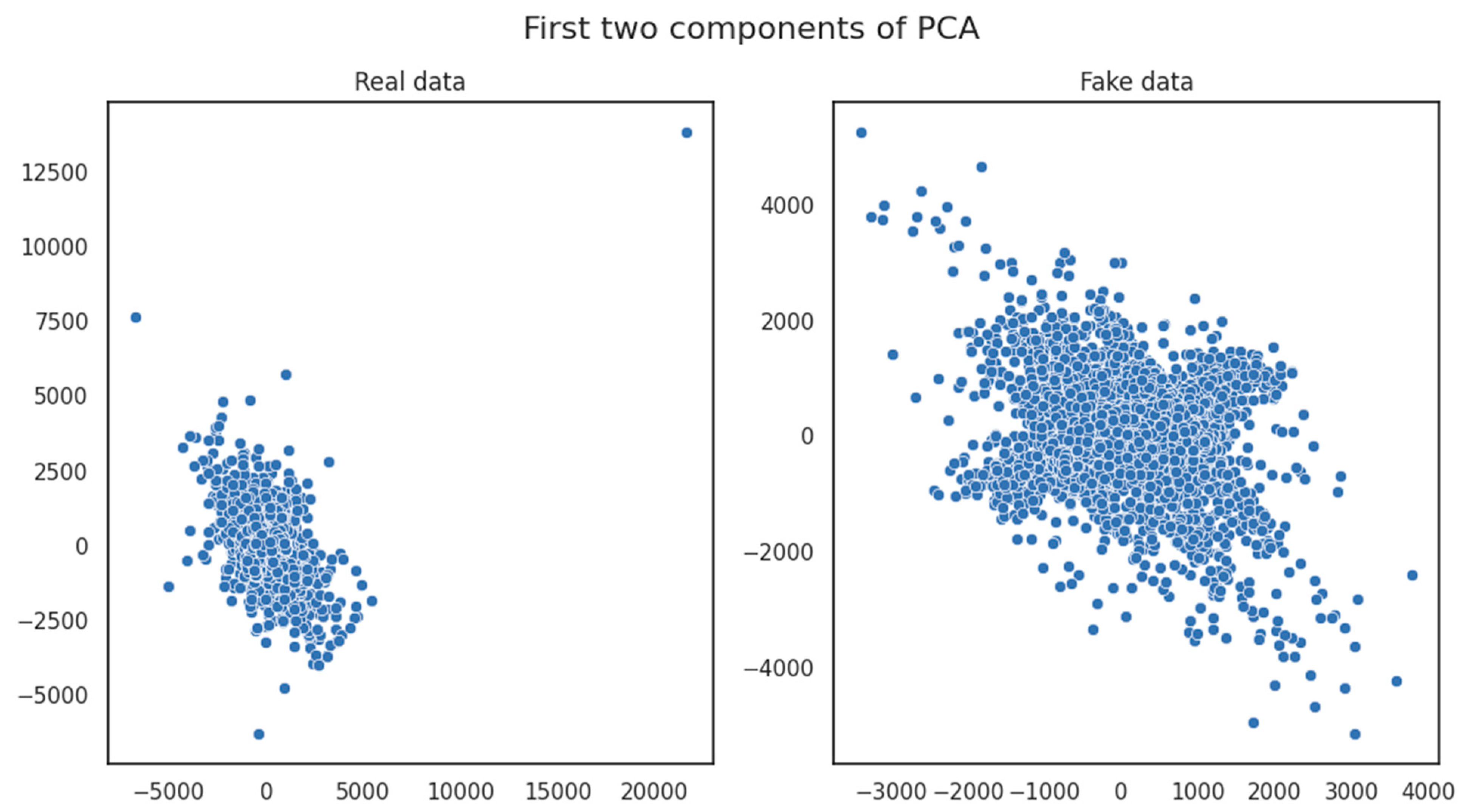

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA) diagrams are employed as a valuable tool in comparing similarity scores between the original and generated datasets. These diagrams offer a graphical representation of how the under-examination dataset’s dimensions align and diverge. By visualizing the distribution of similarity scores through PCA, it was possible to distinguish patterns and trends in the relationship between the compared datasets, illuminating the evolution of their similarity as the GAN model underwent training.

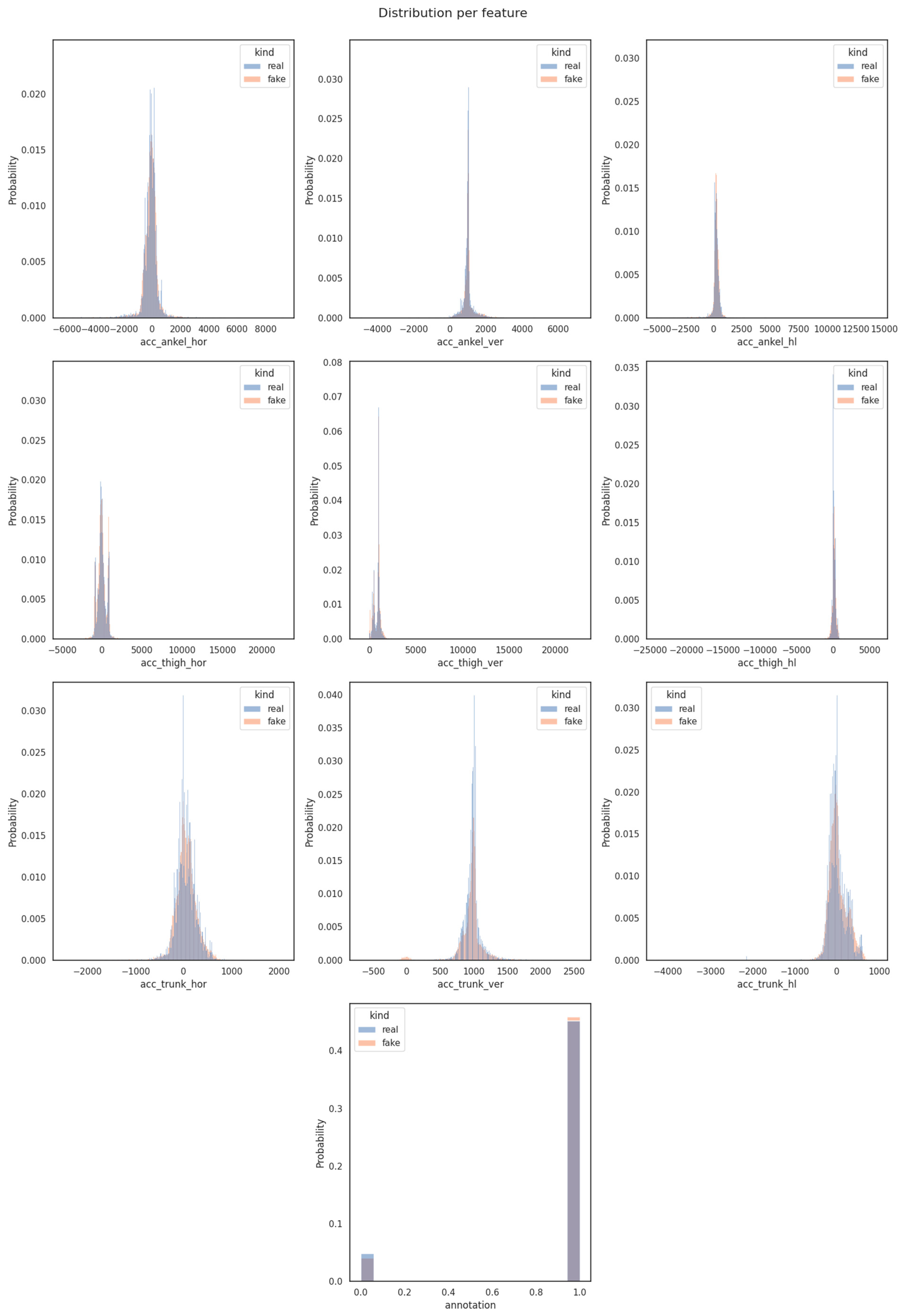

- Distribution diagrams for individual features are instrumental in comparing similarity scores between the original and generated datasets, on a feature-specific level. These diagrams provided a focused view of how each feature’s distribution evolved over time during the FoGGAN model’s training procedure. By analyzing these distributions separately, we gained insights into the similarity fluctuations for each feature, aiding in a more detailed assessment of the synthetic data generation process.

4.2. FoG Incidents Classification Using a DNN Classifiier

4.3. Discussion on the Results

- Data Source Availability: The availability of high-quality, annotated FoG datasets remains a challenge. Gathering and labeling datasets, especially for rare medical conditions like FoG, is time-consuming and resource-intensive. This limitation hinders the scalability and widespread applicability of our approach.

- Clinical Validation: While promising, the high-accuracy results obtained using the FoGGAN-generated data for classification purposes need further clinical validation. Real-world clinical trials and expert assessments are necessary to validate the clinical utility of the synthetic data.

- Data Generalization: The effectiveness of the FoGGAN architecture in generating synthetic data relies on the quality and representativeness of the input dataset. If the initial dataset has limitations or biases, these may also be reflected in the generated data. Careful curation of the input dataset is necessary to mitigate this issue.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Parkinson Disease. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/parkinson-disease (accessed on 16 May 2023).

- Kalia, L.V.; Lang, A.E. Parkinson’s Disease. Lancet 2015, 386, 896–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NINDS. Parkinson’s Disease Information Page. Available online: https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/parkinsons-disease (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Sveinbjornsdottir, S. The Clinical Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease. J. Neurochem. 2016, 139, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giladi, N.; Kao, R.; Fahn, S. Freezing phenomenon in patients with parkinsonian syndromes. Mov. Disord. 1997, 12, 302–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Liu, J.; Tan, Y.; Chen, S. Freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease: Pathophysiology, risk factors and treatments. Transl. Neurodegener. 2020, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaafsma, J.D.; Balash, Y.; Gurevich, T.; Bartels, A.L.; Hausdorff, J.M.; Giladi, N. Characterization of freezing of gait subtypes and the response of each to levodopa in Parkinson’s disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 2003, 10, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson’s Foundation Prevalence & Incidence. Available online: https://www.parkinson.org/understanding-parkinsons/statistics/prevalence-incidence (accessed on 16 May 2023).

- Parkinson’s Europe about Parkinson’s. Available online: https://www.parkinsonseurope.org/about-parkinsons/what-is-parkinsons/ (accessed on 19 May 2023).

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative Adversarial Networks. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1406.2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, C.; Eunice, H. Simulation of Synthetic Diabetes Tabular Data Using Generative Adversarial Networks. Clin. Med. J. 2021, 7, 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, E.; Biswal, S.; Malin, B.; Duke, J.; Stewart, W.; Sun, J. Generating Multi-Label Discrete Patient Records Using Generative Adversarial Networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1703.06490. [Google Scholar]

- Baowaly, M.K.; Lin, C.-C.; Liu, C.-L.; Chen, K.-T. Synthesizing Electronic Health Records Using Improved Generative Adversarial Networks. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2019, 26, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulrajani, I.; Ahmed, F.; Arjovsky, M.; Dumoulin, V.; Courville, A. Improved Training of Wasserstein GANs. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 5769–5779. [Google Scholar]

- Hjelm, R.D.; Jacob, A.P.; Che, T.; Trischler, A.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Boundary-Seeking Generative Adversarial Networks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1702.08431. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, A.E.W.; Pollard, T.J.; Shen, L.; Lehman, L.H.; Feng, M.; Ghassemi, M.; Moody, B.; Szolovits, P.; Anthony Celi, L.; Mark, R.G. MIMIC-III, a Freely Accessible Critical Care Database. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau of National Health Insurance. Department of Health National Health Insurance Research Database. Available online: http://nhird.nhri.org.tw/en/index.htm (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Yang, F.; Yu, Z.; Liang, Y.; Gan, X.; Lin, K.; Zou, Q.; Zeng, Y. Grouped Correlational Generative Adversarial Networks for Discrete Electronic Health Records. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), San Diego, CA, USA, 18–21 November 2019; pp. 906–913. [Google Scholar]

- Arjovsky, M.; Chintala, S.; Bottou, L. Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Sydney, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; pp. 214–223. [Google Scholar]

- Che, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Zhai, S.; Sun, Z.; Liu, Y. Boosting Deep Learning Risk Prediction with Generative Adversarial Networks for Electronic Health Records. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–21 November 2017; pp. 787–792. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, S.; Kakadiya, A.; Mehta, M.; Derasari, R.; Patel, R.; Gandhi, R. Correlated Discrete Data Generation Using Adversarial Training 2018. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.00925. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, J.; Drumright, L.N.; van der Schaar, M. Anonymization Through Data Synthesis Using Generative Adversarial Networks (ADS-GAN). IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2020, 24, 2378–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordon, J.; Yoon, J.; Schaar, M.v.d. PATE-GAN: Generating Synthetic Data with Differential Privacy Guarantees. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Learning Representations, New Orleans, LA, USA, 6–9 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, L.; Lin, K.; Wang, S.; Wang, F.; Zhou, J. Differentially Private Generative Adversarial Network. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.06739. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, W.; He, X. Continuous Patient-Centric Sequence Generation via Sequentially Coupled Adversarial Learning. In Proceedings of the Database Systems for Advanced Applications: 24th International Conference, DASFAA 2019, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 22–25 April 2019; Proceedings, Part II. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 36–52. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Yu, Y. SeqGAN: Sequence Generative Adversarial Nets with Policy Gradient. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, San Francisco, CA, USA, 4–9 February 2017; Volume 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogren, O. C-RNN-GAN: Continuous Recurrent Neural Networks with Adversarial Training 2016. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1611.09904. [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu-Jones, B.K.; Wu, Z.S.; Williams, C.; Lee, R.; Bhavnani, S.P.; Byrd, J.B.; Greene, C.S. Privacy-Preserving Generative Deep Neural Networks Support Clinical Data Sharing. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2019, 12, e005122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteban, C.; Hyland, S.; Rätsch, G. Real-Valued (Medical) Time Series Generation with Recurrent Conditional GANs. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.08633. [Google Scholar]

- Kiyasseh, D.; Tadesse, G.A.; Nhan, L.N.T.; Van Tan, L.; Thwaites, L.; Zhu, T.; Clifton, D. PlethAugment: GAN-Based PPG Augmentation for Medical Diagnosis in Low-Resource Settings. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2020, 24, 3226–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVries, T.; Romero, A.; Pineda, L.; Taylor, G.W.; Drozdzal, M. On the Evaluation of Conditional GANs. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.08175. [Google Scholar]

- Brophy, E. Synthesis of Dependent Multichannel ECG Using Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, Virtual Event, 19–23 October 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 3229–3232. [Google Scholar]

- Hazra, D.; Byun, Y.-C. SynSigGAN: Generative Adversarial Networks for Synthetic Biomedical Signal Generation. Biology 2020, 9, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, H.; Chu, X.; Liu, Q.; Xue, D. Anomaly Detection and Critical SCADA Parameters Identification for Wind Turbines Based on LSTM-AE Neural Network. Renew. Energy 2021, 172, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.-S.; Nguyen, L.-M.; Tojo, S.; Satoh, K.; Shimazu, A. Recurrent Neural Network-Based Models for Recognizing Requisite and Effectuation Parts in Legal Texts. Artif. Intell. Law 2018, 26, 169–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Ye, F.; Fu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Shen, B. Electrocardiogram Generation with a Bidirectional LSTM-CNN Generative Adversarial Network. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torfi, A.; Fox, E.A.; Reddy, C.K. Differentially Private Synthetic Medical Data Generation Using Convolutional GANs. Inf. Sci. 2022, 586, 485–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, N.; Mohammadi, M.; Gorde, K.; Jajodia, S.; Park, H.; Kim, Y. Data Synthesis Based on Generative Adversarial Networks. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2018, 11, 1071–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin-Cheong, K.; Sutter, T.; Vogt, J.E. Generation of Heterogeneous Synthetic Electronic Health Records Using GANs. In Proceedings of the 33rd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2019), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Aggarwal, H.; Rani, R. Data Augmentation Using GAN for Parkinson’s Disease Prediction. In Proceedings of the Recent Innovations in Computing; Singh, P.K., Singh, Y., Kolekar, M.H., Kar, A.K., Chhabra, J.K., Sen, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 589–597. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.-J.; Wang, R.-F.; Wang, J.; Yu, D.-H. Parkinson’s Disease Detection Based on Spectrogram-Deep Convolutional Generative Adversarial Network Sample Augmentation. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 206888–206900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1512.03385. [Google Scholar]

- Noella, R.S.N.; Priyadarshini, J. Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s Disease and Frontotemporal Dementia Using a Generative Adversarial Deep Convolutional Neural Network. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 2845–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anicet Zanini, R.; Luna Colombini, E. Parkinson’s Disease EMG Data Augmentation and Simulation with DCGANs and Style Transfer. Sensors 2020, 20, 2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Aggarwal, H.; Rani, R. Diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease Using Deep CNN with Transfer Learning and Data Augmentation. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 10113–10139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Lenka, A.; Kumar Pal, P. Handwriting Analysis in Parkinson’s Disease: Current Status and Future Directions. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2017, 4, 806–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzotsenidze, E.; Valla, E.; Nõmm, S.; Medijainen, K.; Taba, P.; Toomela, A. Generative Adversarial Networks as a Data Augmentation Tool for CNN-Based Parkinson’s Disease Diagnostics. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, A.; Chitta, K.; Müller, J.; Geiger, A. Projected GANs Converge Faster. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Ranzato, M., Beygelzimer, A., Dauphin, Y., Liang, P.S., Vaughan, J.W., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 34, pp. 17480–17492. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W. Evolution of StyleGAN3. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Electronics and Devices, Computational Science (ICEDCS), Marseille, France, 20–22 September 2022; pp. 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Woodland, M.; Wood, J.; Anderson, B.M.; Kundu, S.; Lin, E.; Koay, E.; Odisio, B.; Chung, C.; Kang, H.C.; Venkatesan, A.M.; et al. Evaluating the Performance of StyleGAN2-ADA on Medical Images. In Proceedings of the Simulation and Synthesis in Medical Imaging; Zhao, C., Svoboda, D., Wolterink, J.M., Escobar, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 142–153. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, H.-Y.; Jiang, L.; Liu, C.; Yang, M.-H.; Yang, W. Regularizing Generative Adversarial Networks under Limited Data. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.03310. [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh, V.; Bilal, E. Detecting Motor Symptom Fluctuations in Parkinson’s Disease with Generative Adversarial Networks. npj Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhidayasiri, R.; Tarsy, D. Movement Disorders: A Video Atlas; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-1-60327-425-8. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.; Chai, Y.; Samtani, S.; Liu, H. Motion Sensor-Based Fall Prevention for Senior Care: A Hidden Markov Model with Generative Adversarial Network (HMM-GAN) Approach. Inf. Syst. Res. 2023, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiner, L.; Juang, B. An Introduction to Hidden Markov Models. IEEE ASSP Mag. 1986, 3, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V. Data_Daphnet_Combined. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/vguptanitj/data-daphnet-combined?resource=download (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Bächlin, M.; Plotnik, M.; Roggen, D.; Maidan, I.; Hausdorff, J.M.; Giladi, N.; Tröster, G. Wearable Assistant for Parkinson’s Disease Patients with the Freezing of Gait Symptom. Trans. Info. Technol. Biomed. 2010, 14, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadi, M.; Agarwal, A.; Barham, P.; Brevdo, E.; Chen, Z.; Citro, C.; Corrado, G.S.; Davis, A.; Dean, J.; Devin, M.; et al. TensorFlow: Large-Scale Machine Learning on Heterogeneous Systems. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1603.04467. [Google Scholar]

- Bhanot, K.; Qi, M.; Erickson, J.S.; Guyon, I.; Bennett, K.P. The Problem of Fairness in Synthetic Healthcare Data. Entropy 2021, 23, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| acc_ankel_hor | numerical | Ankle (shank) acceleration— horizontal forward acceleration |

| acc_ankel_ver | numerical | Ankle (shank) acceleration— Acceleration—vertical |

| acc_ankel_hl | numerical | Ankle (shank) acceleration— horizontal lateral |

| acc_thigh_hor | numerical | Upper leg (thigh) acceleration— horizontal forward acceleration |

| acc_thigh_ver | numerical | Upper leg (thigh) acceleration— vertical |

| acc_thigh_hl | numerical | Upper leg (thigh) acceleration— horizontal lateral |

| acc_trunk_hor | numerical | Trunk acceleration— horizontal forward acceleration |

| acc_trunk_ver | numerical | Trunk acceleration— vertical |

| acc_trunk_hl | numerical | Trunk acceleration— horizontal lateral |

| annotation | numerical | 0 or 1 |

| Generator | ||

|---|---|---|

| Layer (Type) | Output Shape | Number of Parameters |

| dense (Dense) | (None, 1536) | 13,824 |

| dense_1 (Dense) | (None, 1278) | 1,964,286 |

| dense_2 (Dense) | (None, 1024) | 1,309,696 |

| dense_3 (Dense) | (None, 512) | 524,800 |

| dense_4 (Dense) | (None, 384) | 196,992 |

| dense_5 (Dense) | (None, 256) | 98,560 |

| dense_6 (Dense) | (None, 128) | 32,896 |

| dense_7 (Dense) | (None, 64) | 8256 |

| dense_8 (Dense) | (None, 32) | 2080 |

| dense_9 (Dense) | (None, 16) | 528 |

| dense_10 (Dense) | (None, 9) | 153 |

| Total parameters | 4,152,071 | |

| Trainable parameters | 4,152,071 | |

| Non-trainable parameters | 0 | |

| Discriminator | ||

|---|---|---|

| Layer (Type) | Output Shape | Number of Parameters |

| dense_11 (Dense) | (None, 1536) | 13,824 |

| dropout (Dropout) | (None, 1536) | 0 |

| dense_12 (Dense) | (None, 1278) | 1,964,286 |

| dropout_1 (Dropout) | (None, 1278) | 0 |

| dense_13 (Dense) | (None, 1024) | 1,309,696 |

| dropout_2 (Dropout) | (None, 1024) | 0 |

| dense_14 (Dense) | (None, 512) | 524,800 |

| dropout_3 (Dropout) | (None, 512) | 0 |

| dense_15 (Dense) | (None, 384) | 196,992 |

| dropout_4 (Dropout) | (None, 384) | 0 |

| dense_16 (Dense) | (None, 256) | 98,560 |

| dropout_5 (Dropout) | (None, 256) | 0 |

| dense_17 (Dense) | (None, 128) | 32,896 |

| dropout_6 (Dropout) | (None, 128) | 0 |

| dense_18 (Dense) | (None, 64) | 8256 |

| dropout_7 (Dropout) | (None, 64) | 0 |

| dense_19 (Dense) | (None, 32) | 2080 |

| dropout_8 (Dropout) | (None, 32) | 0 |

| dense_20 (Dense) | (None, 16) | 528 |

| dropout_9 (Dropout) | (None, 16) | 0 |

| dense_21 (Dense) | (None, 9) | 153 |

| Total parameters | 4,152,071 | |

| Trainable parameters | 4,152,071 | |

| Non-trainable parameters | 0 | |

| DL Classifier | ||

|---|---|---|

| Layer (Type) | Output Shape | Number of Parameters |

| dense (Dense) | (None, 64) | 640 |

| dropout (Dropout) | (None, 64) | 0 |

| dense_1 (Dense) | (None, 32) | 2080 |

| dropout_1 (Dropout) | (None, 32) | 0 |

| dense_2 (Dense) | (None, 16) | 528 |

| dropout_2 (Dropout) | (None, 16) | 0 |

| dense_3 (Dense) | (None, 8) | 136 |

| dropout_3 (Dropout) | (None, 8) | 0 |

| dense_4 (Dense) | (None, 2) | 18 |

| Total parameters | 3402 | |

| Trainable parameters | 3402 | |

| Non-trainable parameters | 0 | |

| Training/ Evaluation Dataset | Original | Generated | Mixed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training data samples | 912,668 | - | - |

| Evaluation data samples | 228,167 | 60,000 | 288,167 |

| Total data samples | 1,140,835 | 60,000 | 288,167 |

| Metric/Dataset | Original | Generated | Combined |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 90.29% | 92.09% | 90.66% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peppes, N.; Tsakanikas, P.; Daskalakis, E.; Alexakis, T.; Adamopoulou, E.; Demestichas, K. FoGGAN: Generating Realistic Parkinson’s Disease Freezing of Gait Data Using GANs. Sensors 2023, 23, 8158. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23198158

Peppes N, Tsakanikas P, Daskalakis E, Alexakis T, Adamopoulou E, Demestichas K. FoGGAN: Generating Realistic Parkinson’s Disease Freezing of Gait Data Using GANs. Sensors. 2023; 23(19):8158. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23198158

Chicago/Turabian StylePeppes, Nikolaos, Panagiotis Tsakanikas, Emmanouil Daskalakis, Theodoros Alexakis, Evgenia Adamopoulou, and Konstantinos Demestichas. 2023. "FoGGAN: Generating Realistic Parkinson’s Disease Freezing of Gait Data Using GANs" Sensors 23, no. 19: 8158. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23198158

APA StylePeppes, N., Tsakanikas, P., Daskalakis, E., Alexakis, T., Adamopoulou, E., & Demestichas, K. (2023). FoGGAN: Generating Realistic Parkinson’s Disease Freezing of Gait Data Using GANs. Sensors, 23(19), 8158. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23198158