Abstract

This trial evaluated the feasibility of podiatrist-led health coaching (HC) to facilitate smart-insole adoption and foot monitoring in adults with diabetes-related neuropathy. Adults aged 69.9 ± 5.6 years with diabetes for 13.7 ± 10.3 years participated in this 4-week explanatory sequential mixed-methods intervention. An HC training package was delivered to podiatrists, who used HC to issue a smart insole to support foot monitoring. Insole usage data monitored adoption. Changes in participant understanding of neuropathy, foot care behaviours, and intention to adopt the smart insole were measured. Focus group and in-depth interviews explored quantitative data. Initial HC appointments took a mean of 43.8 ± 8.8 min. HC fidelity was strong for empathy/rapport and knowledge provision but weak for assessing motivational elements. Mean smart-insole wear was 12.53 ± 3.46 h/day with 71.2 ± 13.9% alerts not effectively off-loaded, with no significant effect for time on usage F(3,6) = 1.194 (p = 0.389) or alert responses F(3,6) = 0.272 (p = 0.843). Improvements in post-trial questionnaire mean scores and focus group responses indicate podiatrist-led HC improved participants’ understanding of neuropathy and implementation of footcare practices. Podiatrist-led HC is feasible, supporting smart-insole adoption and foot monitoring as evidenced by wear time, and improvements in self-reported footcare practices. However, podiatrists require additional feedback to better consolidate some unfamiliar health coaching skills. ACTRN12618002053202.

1. Introduction

Despite ongoing global efforts to improve foot health outcomes for people with diabetes using a range of strategies [1,2], increasing numbers of people continue to develop preventable diabetes-related foot ulcerations and experience lower limb amputations [1,3,4]. While daily foot checks and regular attendance to primary clinicians for foot monitoring and care are beneficial in maintaining good foot health [5], people with diabetes-related peripheral neuropathy remain at constant risk of developing foot ulcerations due to an inability to detect noxious stimuli, such as the effect of high peak foot pressures, sustained lower peak pressures, or shear [2,6,7]. To augment current preventative foot care regimes, such as orthopaedic footwear and offloading [2], wearable smart foot monitoring devices, including smart socks [8,9,10] and smart sensory insoles [11,12,13,14], are being developed to provide ongoing monitoring of a number of variables in order to provide real-time alerts to the user to undertake protective action in order to prevent injury [8,12,15]. Since the underlying nerve damage caused by diabetes is life-long, people with peripheral neuropathy would need to adopt and use these technologies over many years in order for them to significantly impact foot ulcer incidence. However, patient adherence to currently prescribed footwear and off-loading for ulcer prevention is often poor [2,16]. It is therefore likely that usage of technologies, such as smart insoles that are worn within existing footwear, will also face barriers to adoption, over and above those that exist for footwear, due to a range of psychosocial factors impacting on adoption of diabetes management technologies [17].

Research investigating factors impacting adoption of diabetes management technologies have found many factors interact to affect adoption, such as individuals’ expectation of health benefits from the technology, accessibility, ease of use, social influence from family members, and support from clinicians [17]. While many of these factors are outside the control of clinicians, there is evidence that clinicians can impact patient technology utilisation by the degree they encourage patient use of, and engagement with, the technology and data generated [17]. Two recent Australian studies found generally positive attitudes of regional adults with diabetes and Australian podiatrists towards adopting wearable foot monitoring technology [18,19]. However, both groups had unanswered questions related to device performance and ease of use, and podiatrists had concerns regarding patient-related factors, such as age and footwear usage as well as the clinical time required to support patient smart insole adoption [18,19]. There is scope for podiatrists to play an important role in harnessing their patients’ openness to foot health monitoring technologies to support adoption and utilisation [17]. However, further research is required to optimise podiatrist and patient interactions in order to translate positive adoption intentions into actual adoption.

Health coaching is one approach to enhancing patient motivation and self-efficacy to change and has shown utility in supporting behaviour change in older people [20] and those with chronic illness, such as diabetes [21]. The term ‘health coaching’ has been applied to highly variable interventions, which has made it difficult to define the term [22,23]. Wolever et al. [22] defined multiple elements that comprise health and wellness coaching, including that it is patient centred and that the health professional providing the coaching utilises techniques to support the development of patients’ intrinsic motivation. Health coaching uses a range of techniques to assess a person’s readiness to change, identify health goals and the specific steps and actions required to support achievement of these goals [22,24,25,26,27].

In the context of foot care and foot ulcer prevention for people with diabetes, health coaching could be used to build participant knowledge and address misconceptions about neuropathy and foot care behaviour, encourage the identification of likely outcomes of various behaviours in the presence of neuropathy, and promote the exploration of the personal importance attached to these outcomes [22,23,24,25,27]. This process could build participant self-efficacy in performing foot monitoring and overcoming identified environmental and personal barriers to undertaking protective behaviours [22,24,25,26,27].

The aim of this study was to determine if a health coaching approach to issuing a smart insole with the purpose to augment foot health monitoring is feasible in podiatry practices. Secondary aims were to evaluate changes in patient usage of the smart insole, understanding of neuropathy, and self-reported foot care practices. We hypothesised that:

- A targeted 120-min face-to-face health coaching training session would be sufficient to enable podiatrists to appropriately use health coaching techniques in clinical consultations with participants to support foot monitoring as measured by a health coaching fidelity assessment tool and qualitative data;

- Participants would wear and respond to the smart insole alerts throughout the 28-day trial as measured by prospectively gathered smart insole usage data;

- Participant interpretation of neuropathy and self-reported foot care practices would improve following the health coaching intervention as measured by changes in questionnaire scores and qualitative data; and

- Trialling the smart insole would influence podiatrists’ and participants’ behavioural intention to use the smart insole in the future as measured by changes in modified Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology questionnaire domain scores and qualitative data.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Settings, and Recruitment

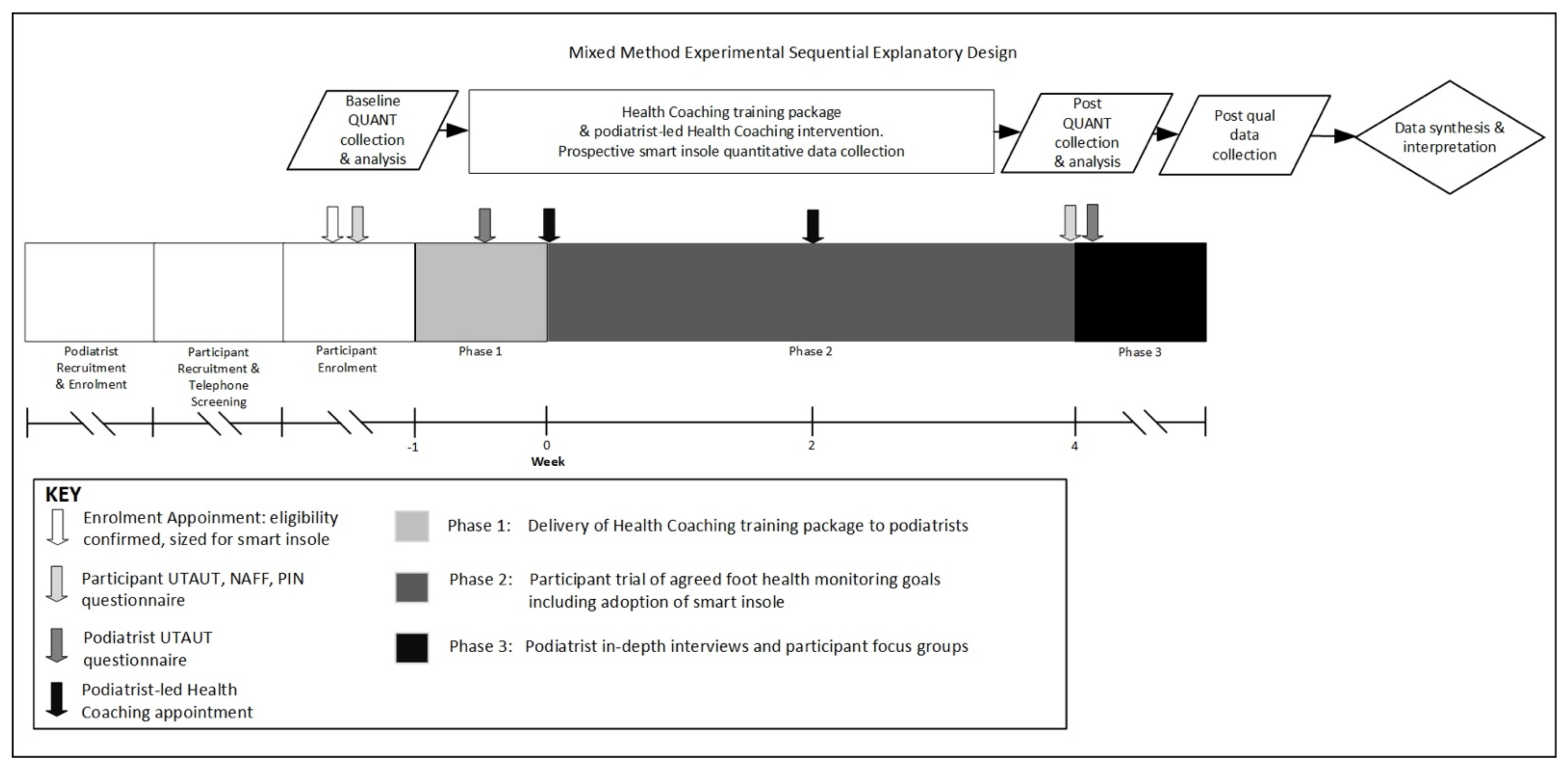

A quantitative dominant (QUANT-qual) mixed-methods intervention with an explanatory sequential core design was utilised (Figure 1) [28]. Ethics approval was granted by Goulburn Valley Health Human Research Ethics Committee (GVH-2019-171432(v2)) 28 June 2019 and La Trobe University Human Research Ethics Committees (HEC19148) 7 June 2019. The trial was registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry ACTRN12618002053202. Figure 1 illustrates the study design, procedure, and timeline. The interventional components occurred over a 5-week period during phases 1 and 2, with phase 3 conducted in the month following the intervention.

Figure 1.

Study design, procedure and timeline.

The trial was located in Shepparton, a regional city in north-central Victoria, Australia. The trial was conducted in one public podiatry practice treating people with high-risk feet and one private practice in order to determine the acceptability of a health coaching approach in these two settings.

Two podiatrists, one practicing in a regional public health setting and the second in a private practice setting, were recruited by email invitation as a convenience sample to participate. The inclusion criteria for podiatrists and participants are provided in Table 1. Both podiatrists invited to participate enrolled and completed the trial as podiatrist health coaches.

Table 1.

Podiatrist and participant inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Participants were recruited by flyers displayed in the waiting areas and podiatry treatment rooms of each of the participating practices. Volunteers contacted a researcher via telephone to obtain further information about the trial and undergo initial telephone screening to determine eligibility. If eligible volunteers were interested, they were booked for a face-to-face screening appointment and underwent an informed consent process, foot assessment, and baseline data collection. Figure 1 outlines the procedures utilised for this study, including the time points, the order in which data collection tools were administered, and the timing of interventions.

2.2. Tools for Data Collection

A tool was developed by the researchers to assess podiatrists’ fidelity to the health coaching training they received in phase 1, and then were to apply during the health coaching appointments at the start of phase 2. Details of the health coaching training package, associated podiatrist and participant resources, and health coaching fidelity assessment tool can be found in Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 2.

Study Tools.

Table 3.

Health coaching training package and written materials.

The foot monitoring technology selected for use in this study was the SurroSense Rx* smart insole manufactured by Orpyx Medical Technologies (Calgary, AB, Canada). The device prospectively collected data on wear time, number of alerts, and alert response. A description of the device characteristics can be found in Table 2.

Three questionnaires were used pre and post phase 2 in this study: the Nottingham Assessment of Functional Footcare (NAFF) questionnaire [31], the Patient Interpretation of Neuropathy questionnaire [32], and a modified version of the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) questionnaire [33,34]. Details of the tools and their use in the study are provided in Table 2.

2.3. Health Coaching Training Package

The 120-min health coaching training package was developed by two researchers, one of whom was a podiatrist and the other a registered nurse with a health coaching background. The training package was delivered to participating podiatrists in phase 1 (Figure 1). The elements of the health coaching training package and podiatrist and participant health coaching resources are outlined in Table 3.

2.4. Podiatrist-Led Health Coaching to Support Foot Health Monitoring

The initial health coaching appointments in phase 2 were expected to take 45 min and were audio-recorded on a password-protected smart phone and delivered to the trial’s health coach on a USB for later assessment of each podiatrists’ fidelity to the health coaching approach. During the appointments, podiatrists worked with participants to identify individual foot health monitoring goals, a component of which included the issue of the smart insole for use over the four-week trial. The strategies and tools podiatrists were to use during the health coaching intervention with participants are outlined in Table 3. The participants attended a follow-up appointment a fortnight later. The duration of the review consultations was noted by the podiatrists, but these were not audio recorded.

2.5. Quantitative Data Collection and Analysis

The granular raw data from each participant’s SurroSense Rx*smart watch, obtained from Orpyx Medical Technologies (Calgary, AB, Canada), was analysed using a program designed in LabVIEW (version 16; National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA). The researchers used the same definitions for the triggering of an alert as utilised by Abbott et al. [11]. An alert was successfully responded to if pressure on the affected part of the foot was off-loaded within 3 min of the alert being generated. The alert would remain active until pressure was reduced on the area, with the participant receiving reminders to off-load every 3 min. Days where insole wear time was recorded as less than 60 min due to device malfunctions were excluded from analyses. In total, 7 out of a possible total of 280 wear days’ data (2.5%) were excluded from analysis due to technology malfunctions.

Malfunctions included disconnection of leads from the transmission pod, and disconnection between the insole and smart watch. Days where participants had not attempted to wear the device were still included in the analyses. For two participants who had experienced technological malfunctions who chose to continue to wear the device beyond day 28, the additional valid wear days were included in the analyses in substitution for the days excluded due to technology issues.

Descriptive statistics were used for demographic, questionnaire, and insole usage data. Ratio data were presented as mean and standard deviation, and nominal data were presented as proportions. Statistical significance for analyses was set at p ≤ 0.05. A trend towards significance was set at p < 0.10. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 26.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Mean domain scores measured on a continuous 5-point Likert scale for the UTAUT and PIN questionnaire were calculated, and total scores for the NAFF questionnaire and health coaching fidelity tool were calculated. Insole usage data were presented as mean hours worn per valid wear day, mean daily number of alerts, and mean percentage of alerts not successfully responded to. Paired sample t-tests were used to assess changes in pre and post mean domain PIN and UTAUT scores.

Mixed-model analyses of variance were conducted to assess the impact of practice setting (between) and time (within) on weekly insole wear, number of alerts, number of alerts not responded to, percentage of alerts not successfully responded to, and the self-reported foot care behaviours of participants as measured by the NAFF over the four-week trial. Significant interaction effects were interpreted to indicate that the practice setting influenced the pattern of response over time. Where the interaction effect did not reach significance, the main effects of practice setting and time were consulted. Significant timing effects were further explored using Bonferroni–Holm adjusted pairwise comparisons.

2.6. Qualitative Data Collection

In phase 3, focus group and in-depth interviews were conducted to enable participants to provide context to, and exploration of, the quantitative data and the semi-open-ended UTAUT responses [28]. In particular, it was an opportunity for participants and podiatrists to relate their experiences of the health coaching approach taken to foot monitoring and the process of adopting a smart insole. Focus group questions included ‘Did the (health coaching) consultations with your podiatrist impact your understanding of nerve damage in your feet and how to look after your feet?’, ‘Did the written information provided to you, including the instruction manual, Quick Start Guide, laminated response to alerts pictograph and the action plan you completed enable you to confidently use the smart insole at home, resolve alerts or other issues?’ In-depth interview questions included ‘Was the health coaching training package understandable, and did it go into sufficient depth?’, ‘How did the health coaching skills impact your communication with your client and the provision of foot care/monitoring information, including the device issuing?’ Focus group and in-depth interviews were audio recorded using VoiceMemo on an i-phone 8 password-protected phone and then transcribed verbatim and analysed thematically using NVivo version 12.6.0 3841 (QRS International Pty Ltd., Chadstone, Australia). All coding was completed independently by two authors, with codes then being discussed to develop themes. Focus group and in-depth interview data related to technology adoption utilised thematic coding derived from the UTAUT domains. All other data was coded to describe the meaning of the text, then grouped into categories and then themes that could explain the quantitative data [36].

While it was anticipated that all participants would attend a focus group, 7 out of 10 attended on the day. Four out of five attended the private arm focus group; one woman aged 71 years with type 2 diabetes for 19 years, and four men aged between 68 to 79 years all with type 2 diabetes for between 10 to 18 years. Three out of five public arm participants attended their scheduled focus group. One failed to attend due to being out of the region and one could not be contacted to confirm the date and time of the session. One woman aged 58 years with type 1 diabetes for 34 years, and two men aged between 72 and 74 years both with type 2 diabetes for between 10 to 23 years attended the public arm focus group. Both podiatrists attended an in-depth interview, one male aged 32 years employed in public practice with 8 years professional practice and one male aged 58 years from private practice with 37 years of professional practice.

3. Results

The podiatrist-led health coaching appointments took a mean of 43.8 ± 8.8 min for the initial appointment and 29.6 ± 12.9 min for the review (Table 4). Participants used the smart insole for a mean of 12.53 ± 3.46 h per day and received a mean of 22.96 ± 12.9 daily alerts during the trial, of which they failed to effectively offload a mean of 71.2 ± 13.9 percent of alerts within 3 min of being generated (Table 4).

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics n = 10.

Table 5 provides the results for the health coaching fidelity tool. The mean health coaching fidelity score was 30.8 ± 2.0 out of a maximum possible total of 58. The health coaching fidelity tool revealed that podiatrists’ use of health coaching techniques related to motivational elements, including assessing participants’ readiness to adopt a smart insole and practice protective foot care behaviours (HC 4), the importance they attached to smart insole adoption and protective footcare behaviours (HC 5, 12, 13), and their confidence in their ability to do this (HC 14, 15), were either not used or only partially used (Table 5). While elements of the intervention related to being participant centred (HC 2, 3, 10, 11) demonstrated higher mean values than the motivational elements, their use was still inconsistent. Podiatrists most consistently used elements of the intervention related to providing knowledge to participants on how to use the smart insole, the nature of neuropathy and protective footcare behaviours (HC 6, 7, 8, 9, 16), and those related to demonstrating empathy and building rapport (HC 1, 17).

Table 5.

Health coaching fidelity assessment tool n = 10.

Practice setting did not influence the pattern of response over time for the variables mean daily hours per week of insole wear, mean daily number of alerts per week, mean daily number of alert non-responses per week, mean daily percentage per week of alert non-responses, and NAFF scores (interaction effect: p ≥ 0.236) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Mixed model ANOVA.

There was no significant main effect for time on mean daily hours of insole wear F(3,6) = 1.194, p = 0.389, η2 = 0.374 and mean daily percentage of alert non-responses F(3,6) = 0.272, p = 0.843, η2 = 0.12, which remained consistent over the four weeks of the trial. However there was a significant main effect for time on the mean daily alerts per week, F(3,6) = 4.92, p = 0.047, η2 = 0.711, and mean daily alert non-responses per week F(3,6) = 5.38, p = 0.035, η2 = 0.738, which significantly reduced from week 1 to week 4, p = 0.043. There was also a trend towards a significant change over time on NAFF total score F(1,8) = 4.29, p = 0.072, η2 = 0.349, with both groups increasing their mean total NAFF score compared to baseline (Table 6).

Practice setting did not significantly affect insole usage or response during the four-week trial, with no significant main effects for mean daily insole wear F(1,8) = 0.135, p = 0.723, η2 = 0.017, mean daily alerts F(1,8) = 0.665, p = 0.438, η2 = 0.077, mean daily alert non-responses F(1,8) = 1.136, p = 0.318, η2 = 0.124, and mean daily percentage of alert non-responses F(1,8) = 0.162, p = 0.698, η2 = 0.020. However, there was a trend toward significance for the main effect of practice setting and changes in NAFF total score F(1,8) = 5.012, p = 0.056, η2 = 0.385, with private participants having lower mean pre and post NAFF scores than public participants (Table 6).

UTUAT scores related to future adoption intentions of the smart insole demonstrated significant post trial reductions in mean participant attitude t = 2.6, p = 0.028, and behavioural intention t = 3.4, p = 0.008. There was also a trend towards a significant reduction in participants’ performance expectancy t = 2.15, p = 0.060 and an increase in self-efficacy t = −1.96, p = 0.081 from baseline to post trial (Table 7). Changes in pre and post PIN domain mean scores demonstrated a significant improvement in domains evaluating participants’ understanding of the causes of neuropathy and foot ulcers (item C1) t = −2.74, p = 0.023, foot ulcer onset (item TL) t = −2.70, p = 0.024, as well as allocation of responsibility for developing foot ulcers (item C2) t = −3.03, p = 0.014 (Table 7).

Table 7.

Questionnaire results n = 10.

3.1. Qualitative Results

3.1.1. Health Coaching Intervention

In the in-depth interviews, the podiatrists reported that they felt that the two-hour education session, with the additional written information, was sufficient to be able to coach participants in foot health monitoring and the use of a smart insole. However, the private podiatrist felt that the training would have been enhanced by receiving feedback on their performance following their initial health coaching consultation to assist in consolidating the procedure (Table 8).

Table 8.

Podiatrist in-depth interview results.

The health coaching education prompted the podiatrists to reconsider their approach to communicating with participants, particularly relating to the provision of knowledge and tailoring the session to each individual’s needs. In particular, podiatrists modified their usual practice by utilising health coaching tools, such as Teach Back, to confirm participant understanding in order to correct misunderstandings and fill knowledge gaps. For the private podiatrist, this process also enhanced and improved his relationship with participants (Table 8).

Participants in the private focus group reported that the way information was delivered by the podiatrist gave them far greater insights into their condition and how to care for their feet than previous education, and that the information was more personal and relevant to them (Table 9). Participants in the public focus group felt that the podiatrist made themselves ‘available’ throughout the consultation, and that his delivery of foot care knowledge and overall execution of the health coaching sessions was effective. However, they felt that the information provided regarding the nature of neuropathy and recommended protective foot care behaviours confirmed their existing understanding rather than providing them with new information (Table 9). Participants in both focus groups reported that the health coaching sessions and written information provided them with sufficient knowledge and confidence to monitor their feet and adopt the smart insoles successfully (Table 9).

Table 9.

Participant focus group results.

3.1.2. Performance Expectancy

Participants and podiatrists could see the potential benefits of foot monitoring technologies, like the smart insole, in providing greater knowledge about foot pressure areas. However, they felt that further development of the device utilised in this trial would make it more user friendly (Table 8 and Table 9). Some participants in the private arm were perplexed by the alerts they received and how the device defined ‘high pressure’, particularly in the context of being seated. For some private arm participants, the feedback appeared random and significantly diminished their level of trust in the feedback they received (Table 9). However, participants in the public arm who had previously experienced foot ulcerations understood why they were being alerted to pressure in a specific foot location and believed the device was providing accurate feedback but felt that there was little they could do to permanently address the pressure issues due to underlying structural foot deformities (Table 9).

3.1.3. Effort Expectancy

Participants found some elements of the device, such as charging the batteries and connecting the innersoles to the smart watch, to be easy when everything functioned as intended. However, participants experienced frustration or a sense of added burden when elements malfunctioned or when they received repeated alerts that became intrusive during daily tasks, such as driving or preparing meals. Public arm participants’ comments indicate that they found using the smart insoles less burdensome than participants in the private arm (Table 9).

3.1.4. Social Influence

Socially, some participants found that the audible alarms were disruptive when they were socialising with others, reporting that they were questioned about the alarms and the presence of transmission pods, which some found off-putting (Table 9).

Podiatrists’ attitudes towards the smart insole were strongly influenced by their patients’ (participants) experiences and opinions of the device, in particular the private podiatrist. Poor participant experiences with the smart insole exerted social influence that negatively impacted podiatrists’ intentions towards adopting the device into practice (Table 8).

3.1.5. Facilitating Conditions

Participants reported that they had the resources required to successfully use the smart insole. However, the restrictiveness of having to wear lace-up or Velcro-enclosed footwear to use the device was seen as a deterrent for those who preferred flexibility in the type of footwear that they wore through the day, particularly when at home (Table 9).

Podiatrists believed the health coaching approach to supporting foot health monitoring, including the issuing and education in the use of a smart insole, was suitable in both public and private settings in terms of the length of consultation times and practice resources required (Table 8).

3.1.6. Behavioural Intention

While participants and podiatrists were confident in their capacity to use the smart insole and could see potential benefits to the device, particularly for those who had experienced previous foot ulcers, neither group intended to adopt this version of a smart insole in the future. However, both participants and podiatrists believed that with further development, foot monitoring technologies could play a valuable role in preventing foot ulcerations, and they would be open to exploring future iterations of a smart insole (Table 8 and Table 9).

4. Discussion

The use of health coaching techniques to support foot health monitoring is feasible in both private and public podiatry practice settings, as evidenced by the mean duration of heath coaching appointments and focus group and in-depth interview responses. Podiatrists using health coaching techniques supported participants’ foot monitoring and adoption of a smart insole over a four-week period, as evidenced by insole usage data, improvements in total NAFF scores and individual PIN domains, and confirmed by focus group responses. However, the health coaching fidelity scores indicate that despite the education podiatrists received in using a range of health coaching strategies and the importance of being participant centred, podiatrists at times directed the consultations, rather than being primarily participant directed. Podiatrists were most comfortable providing education, building rapport, and demonstrating empathy to participants, skills that they were familiar with utilising in usual clinical practice rather than fully embracing more unfamiliar health coaching techniques.

Low health coaching fidelity scores in the domains related to improving participant motivation and moving through the stages of change could have been due to the fact that participants in this study were already motivated, as evidenced by the high baseline UTAUT behavioural intention scores toward smart insole adoption. Therefore, the podiatrists might have made assumptions about participant motivation being high for all aspects of foot health monitoring rather than explicitly confirming each element. However, once podiatrists had confirmed participant readiness to undertake change actions, it would have then been appropriate to move beyond the motivational elements [27]. The 120-min training package without further reinforcement was insufficient to consolidate unfamiliar health coaching skills to podiatrists’ practice. As one podiatrist stated in the in-depth interview, consolidating these skills would have been helped by receiving feedback about the quality of their health coaching technique immediately following their first appointment. Receiving ongoing feedback to consolidate coaching skills has been shown to improve fidelity in other targeted behaviour change interventions [37]. In future, an opportunity for more feedback should be incorporated into this type of targeted health coaching intervention to further support consolidation of trainee skills in order to improve their capacity to support participant self-determination [27,37].

The mean of 12.5 ± 3.5 h of smart insole and footwear daily use indicates that participants successfully adopted the insole and complied with directions to wear it consistently throughout the study, exceeding the 60% and approaching the 80% of the day threshold for shoe wear suggested to reduce ulceration recurrence [7,38]. This result was considerably higher than previous studies using a similar device without health coaching to support adoption, but it must be noted the other trials were for longer durations. A three-month trial had a mean of 5.4 ± 3.4 h per day for smart insole use [12], and an 18-month RCT reported a median of 6.1 h (range 4.3–7.6) of daily wear time [11]. However, while participants in this study were diligent in their daily wear, there was a relatively low percentage of alerts that were effectively off-loaded within the prescribed three-minute time frame, even with a significant decline in alert frequency over the four weeks. Najafi et al. [12] reported that their high-alert group, which they defined as receiving a mean of 0.75 alerts per hour, improved their successful response to alerts over time compared to their low-alert group but posited that there was likely an upper threshold at which additional alerts would lead to declining adherence. It is likely, based on focus group responses, that participants in this trial, who received a mean of 1.83 alerts per hour of wear, developed response fatigue, contributing to the low percentage of successful responses.

Despite the inconsistent application of motivational elements of the intervention, the focus group and in-depth interview responses indicate that the health coaching approach did improve communication with participants and, for the private practice participants, comprehension and internalisation of the nature of neuropathy and the personal implications for their foot health. The impact of this internalisation of foot health appears to be borne out by changes in the NAFF total score and some PIN domains following the intervention. The increase in NAFF scores reflects self-reported improvements in protective foot care behaviours by participants, which might reflect that podiatrists were successful in supporting participants’ sense of autonomy and competence in foot health monitoring, a key goal of coaching [22,27]. However, improvements in these scores could also have occurred simply as a biproduct of participation in the trial leading to a greater awareness of the need to monitor their feet during the study.

Participant dissatisfaction with elements of insole usage were reflected in the significant reduction in post mean participant attitude and behavioural intention towards the smart insole. These results indicate that the lived experience of using the insole negatively impacted participants’ perceptions of the device. This finding contrasted with Najafi et al. [12], who found that participants who received significantly fewer alerts per hour compared to the current study had positive adoption intentions towards a similar device at the end of a three-month trial.

The trend towards a significant reduction in mean UTAUT performance expectancy from baseline to post trial when considered in the context of the focus group and in-depth interview responses indicates that the performance, or functionality, of the device used in this study did not meet participants’ or podiatrists’ original expectations. Previous research in a similar patient population investigating factors that impacted intention to adopt a smart insole found that performance expectancy moderated attitude, which was a predictor of adoption intention [18]. It is therefore unsurprising that the reduction in performance expectancy and attitude negatively impacted our participants’ future adoption intentions. Another study investigating factors impacting Australian podiatrists’ intentions to adopt smart insoles in practice [19] found that performance expectancy was the sole predictor of behavioural intention. Again, it is unsurprising, given a reduction in podiatrists’ performance expectancy mean scores from baseline, that there was also a reduction in podiatrists’ mean post trial behavioural intention score. However, both participants and podiatrists still emphasised that they saw value in real-time foot monitoring and were open to trying future versions of this or other foot monitoring devices.

It is likely that continuing developments in foot monitoring technology would address many of our participants’ concerns and better support adoption and utilisation in the future. For example, the new generation of Orpyx SI Sensory Insole shows promise [39], addressing many of the technological and social issues identified in this study and providing additional desired functionalities. By enabling greater flexibility of alert notifications, the newer generation of insole might address the issue of alert frequency, which was so concerning for our participants, and the additional automation of device functions is likely to reduce the level of effort required for use. The integration of external components within the body of the custom-milled form addresses some of the social concerns identified by our participants related to the visibility of external components and also enables use in wider variety of footwear, a functionality identified in a previous study to be desired by Australian podiatrists [19]. Furthermore, the addition of temperature in conjunction with pressure monitoring is a physiologic parameter the podiatrists in this study identified as being of clinical importance, and which might make it more attractive to Australian podiatrists when considering clinical adoption. Dialogue between device developers and end users is likely to support a process of ongoing innovation and development that will make future foot monitoring technologies more user friendly and attractive to target populations.

Focus group discussions regarding a lack of trust in the alerts by some private practice participants, and the feeling that the insoles alerted when they did not perceive there to be ‘high pressure’ indicates that participants required further exploration of the types of plantar pressures that can lead to tissue damage (peak versus sustained) during their health coaching sessions. Future research using health coaching to support foot monitoring technology adoption should highlight the need to explore participant understanding of the way a device monitors and measures target variables and how the variables relate to their foot ulcer risk. The smart insole used did not report peak pressures but rather pressures >35 mmHg, which were sustained for 95–100% of the time, and if maintained for 15 min or more, generated an alert. Some private practice participants, none of whom had had previous foot ulcerations, struggled to understand how they could have ‘high’ pressure on their feet while sitting down with their feet resting on the floor. A lack of trust in alerts might have also contributed to the relatively low percentage of successful alert responses in this trial. Our participants’ experiences of receiving regular static alerts are consistent with a recent study where a majority of participants reported receiving alerts while in static positions, and resolved alerts with regular bouts of foot movement [11]. While Abbott et al. [11] reported statistically significantly fewer cumulative numbers of foot ulceration sites in their intervention group compared to their control group, they did not find a statistically significant difference between the intervention and control groups in the overall number of people who developed ulceration. While it is encouraging that the intervention group developed fewer numbers of ulcers, podiatrists and participants in our study required compelling evidence that use of a smart insole would significantly decrease the likelihood that they would develop foot ulcers (performance expectancy) in order to support ongoing usage.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study demonstrate that it is feasible to use a health coaching approach to issuing a smart insole in the context of foot care health monitoring for adults with diabetes. A strength of health coaching is that the strategies and tools used in this approach, once consolidated by the practitioner, can be applied to behaviour change in a wide range of contexts, including to support different types of technology adoption. However, while a 120-min training session for podiatrists was sufficient for them to successfully issue the smart insole and improve participant internalisation of protective foot practices and knowledge, unfamiliar aspects of the health coaching approach were not sufficiently consolidated. This indicates that further refinement of the package, which incorporates additional trainee feedback, utilisation of fidelity assessment for review appointments, and further development and validation of the fidelity tool, is warranted. After the package and fidelity tool have been refined, they should be tested in a larger prospective trial over a longer duration to assess the influence of health coaching on foot monitoring behaviour change over time, including smart insole wear and alert responses. Additional study limitations are the small sample size, the potential for self-selection bias in those who volunteered to participate compared to those who did not, and that changes in foot care practices were self-reported through questionnaire and focus group responses without objective confirmation.

Despite participants’ successful adoption of the smart insole during the trial, their attitude and behavioural intention towards future adoption were negatively impacted by their experiences. However, focus group and in-depth interview responses indicate that this population remain optimistic about the role of technology in supporting foot monitoring. Participant and podiatrist comments indicate that evidence of device efficacy in preventing foot ulcerations would improve trust, and additional device refinement to improve performance would all increase the likelihood of future adoption. Foot monitoring technology developers should continue to invest in prospective trials to assess device efficacy in preventing foot ulceration and consult with target users regarding device design features.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M.M., B.M.P., L.C. and M.I.C.K. Methodology, E.M.M., B.M.P., L.C. and M.I.C.K.; Software, M.I.C.K.; Validation, E.M.M., B.M.P., L.C. and M.I.C.K.; Formal Analysis, E.M.M., B.M.P., L.C. and M.I.C.K.; Investigation, E.M.M.; Resources, E.M.M. and L.C.; Data Curation, E.M.M.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, E.M.M.; Writing—E.M.M., B.M.P., L.C. and M.I.C.K.; Visualization, E.M.M., B.M.P., L.C. and M.I.C.K.; Supervision, B.M.P. and M.I.C.K.; Project Administration, E.M.M.; Funding Acquisition, M.I.C.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partly funded by La Trobe University, Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship, Orpyx Medical Technologies (Calgary, Alberta, CA, USA).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Goulburn Valley Health (GVH-2019-171432(v2)) 28 June 2019 and La Trobe University Human Research Ethics Committees (HEC19148) 7 June 2019.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Bendigo Tertiary Education Anniversary Foundation and Holsworth Research Initiative’s support of Michael Kingsley’s research.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders reviewed the manuscript prior to submission; however, the funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Lazzarini, P.A.; van Netten, J.J.; Fitridge, R.A.; Griffiths, I.; Kinnear, E.M.; Malone, M.; Perrin, B.M.; Prentice, J.; Wraight, P.R. Pathway to ending avoidable diabetes-related amputations in Australia. Med. J. Aust. 2018, 209, 288–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Netten, J.J.; Lazzarini, P.A.; Armstrong, D.G.; Bus, S.A.; Fitridge, R.; Harding, K.; Kinnear, E.; Malone, M.; Menz, H.B.; Perrin, B.M.; et al. Diabetic Foot Australia guideline on footwear for people with diabetes. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2018, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazzarini, P.A.; Gurr, J.M.; Rogers, J.R.; Schox, A.; Bergin, S.M. Diabetes foot disease: The Cinderella of Australian diabetes management? J. Foot Ankle Res. 2012, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, A. IDF Clinical Practice Recommendation on the Diabetic Foot: A guide for healthcare professionals. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2017, 127, 285–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bus, S.; Van Netten, S.; Lavery, L.; Monteiro-Soares, M.; Rasmussen, A.; Jubiz, Y.; Price, P. IWGDF guidance on the prevention of foot ulcers in at-risk patients with diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2016, 32, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzarini, P.A.; Crews, R.T.; van Netten, J.J.; Bus, S.A.; Fernando, M.E.; Chadwick, P.J.; Najafi, B. Measuring Plantar Tissue Stress in People with Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy: A Critical Concept in Diabetic Foot Management. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2019, 13, 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waaijman, R.; De Haart, M.; Arts, M.L.J.; Wever, D.; Verlouw, A.J.W.E.; Nollet, F.; Bus, S.A. Risk Factors for Plantar Foot Ulcer Recurrence in Neuropathic Diabetic Patients. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 1697–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, B.; Mohseni, H.; Grewal, G.S.; Talal, T.K.; Menzies, R.A.; Armstrong, D.G. An Optical-Fiber-Based Smart Textile (Smart Socks) to Manage Biomechanical Risk Factors Associated with Diabetic Foot Amputation. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2017, 11, 668–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Nahas, M.; El-Shazly, S.; El-Gamel, F.; Motawea, M.; Kyrillos, F.; Idrees, H. Relationship between skin temperature monitoring with Smart Socks and plantar pressure distribution: A pilot study. J. Wound Care 2018, 27, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyzelman, A.M.; Koelewyn, K.; Murphy, M.; Shen, X.; Yu, E.; Pillai, R.; Fu, J.; Scholten, H.J.; Ma, R. Continuous Temperature-Monitoring Socks for Home Use in Patients with Diabetes: Observational Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e12460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, C.A.; Chatwin, K.E.; Foden, P.; Hasan, A.N.; Sange, C.; Rajbhandari, S.M.; Reddy, P.N.; Vileikyte, L.; Bowling, F.L.; Boulton, A.J.M.; et al. Innovative intelligent insole system reduces diabetic foot ulcer recurrence at plantar sites: A prospective, randomised, proof-of-concept study. Lancet Digit. Health 2019, 1, e308–e318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, B.; Ron, E.; Enriquez, A.; Marin, I.; Razjouyan, J.; Armstrong, D.G. Smarter Sole Survival: Will Neuropathic Patients at High Risk for Ulceration Use a Smart Insole-Based Foot Protection System? J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2017, 11, 702–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, A.; Walter, I.; Alhajjar, A.; Leuckert, M.; Mertens, P.R. Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial to test for preventive effects of diabetic foot ulceration by telemedicine that includes sensor-equipped insoles combined with photo documentation. Trials 2019, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonso, B.B.A.R.; Rao, S.; Everett, B.M.M.B.; Chiu, F.M.E.S. Novel Pressure-Sensing Smart Insole System Used for the Prevention of Pressure Ulceration in the Insensate Foot. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.-Glob. Open 2017, 5, e1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, B.; Reeves, N.D.; Armstrong, D.G. Leveraging smart technologies to improve the management of diabetic foot ulcers and extend ulcer-free days in remission. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2020, 36, e3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, D.G.; Boulton, A.J.M.; Bus, S.A. Diabetic Foot Ulcers and Their Recurrence. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 2367–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, E.M.; Perrin, B.M.; Kingsley, M.I. Enablers and barriers to using two-way information technology in the management of adults with diabetes: A descriptive systematic review. J. Telemed. Telecare 2018, 24, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, E.M.; Perrin, B.M.; Hyett, N.; Kingsley, M.I.C. Factors influencing behavioural intention to use a smart shoe insole in regionally based adults with diabetes: A mixed methods study. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2019, 12, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, E.M.; Perrin, B.M.; Kingsley, M.I.C. Factors influencing Australian podiatrists’ behavioural intentions to adopt a smart insole into clinical practice: A mixed methods study. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2020, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.S.; Sherrington, C.; Amorim, A.B.; Dario, A.B.; Tiedemann, A. What is the effect of health coaching on physical activity participation in people aged 60 years and over? A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Br. J. Sports Med. 2017, 51, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirbaglou, M.; Katz, J.; Motamed, M.; Pludwinski, S.; Walker, K.; Ritvo, P. Personal Health Coaching as a Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Self-Management Strategy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am. J. Health Promot. 2018, 32, 1613–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolever, R.Q.; Simmons, L.A.; Sforzo, G.A.; Dill, D.; Kaye, M.; Bechard, E.M.; Southard, M.E.; Kennedy, M.; Vosloo, J.; Yang, N. A Systematic Review of the Literature on Health and Wellness Coaching: Defining a Key Behavioral Intervention in Healthcare. Glob. Adv. Health Med. 2013, 2, 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, J.M. Health Coaching: A Concept Analysis. Nurs. Forum 2013, 49, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brega, A.G.; Barnard, J.; Mabachi, N.M.; Weiss, B.D.; DeWalt, D.A.; Bach, C.; Cifuentes, M.; Albright, K.; West, D.R. AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit, 2nd ed.; Rockville, M.D., Ed.; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2015; pp. 1–175. [Google Scholar]

- Dinh, T.T.H.; Bonner, A.; Clark, R.; Ramsbotham, J.; Hines, S. The effectiveness of the teach-back method on adherence and self-management in health education for people with chronic disease: A systematic review. JBI Evid. Synth. 2016, 14, 210–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M. Theoretical Foundations of Health Education and Health Promotion, 3rd ed.; Jones & Bartlett Publishers: Burlington, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 77–163. [Google Scholar]

- Sohl, S.J.; Birdee, G.; Elam, R. Complementary Tools to Empower and Sustain Behavior Change. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2016, 10, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schaper, N.C.; Van Netten, J.J.; Apelqvist, J.; Bus, S.A.; Hinchliffe, R.J.; Lipsky, B.A.; IWGDF Editorial Board. Practical Guidelines on the prevention and management of diabetic foot disease (IWGDF 2019 update). Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2020, 36, e3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop-Busui, R.; Boulton, A.J.; Feldman, E.L.; Bril, V.; Freeman, R.; Malik, R.A.; Sosenko, J.M.; Ziegler, D. Diabetic Neuropathy: A Position Statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, N.; Jeffcoate, W.; Ince, P.; Smith, M.; Radford, K. Validation of a new measure of protective footcare behaviour: The Nottingham Assessment of Functional Footcare (NAFF). Pract. Diabetes Int. 2007, 24, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vileikyte, L.; Gonzalez, J.S.; Leventhal, H.; Peyrot, M.F.; Rubin, R.R.; Garrow, A.; Ulbrecht, J.S.; Cavanagh, P.R.; Boulton, A.J. Patient Interpretation of Neuropathy (PIN) Questionnaire: An instrument for assessment of cognitive and emotional factors associated with foot self-care. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 2617–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohnke, A.; Cole, M.L.; Bush, R. Incorporating UTAUT predictors for understanding home care patients’ and clinician’s acceptance of healthcare telemedicine equipment. J. Tech. Manag. Innov. 2014, 9, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D.; Harris, E.; Wise, W. Theory in a Nutshell: A Practical Guide to Health Promotion Theories, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: North Ryde, Australia, 2010; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Liamputtong, P.; Serry, T. Making sense of qualitative data. In Research Methods in Health: Foundations for Evidence-Based Practice, 2nd ed.; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Melbourne, Australia, 2013; pp. 365–379. [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Goodrich, D.E.; Kim, H.M.; Holleman, R.G.; Gillon, L.; Kirsh, S.R.; Richardson, C.R.; Lutes, L.D. Development and validation of the ASPIRE-VA coaching fidelity checklist (ACFC): A tool to help ensure delivery of high-quality weight management interventions. Transl. Behav. Med. 2015, 6, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantelau, E.; Haage, P. An Audit of Cushioned Diabetic Footwear: Relation to Patient Compliance. Diabet. Med. 1994, 11, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orpyx Medical Technologies Inc. Instructions for Use v 1.2, Orpyx SI Sensory Insoles; Orpyx Medical Technologies Inc.: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).