Smartphone Apps in the Context of Tinnitus: Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

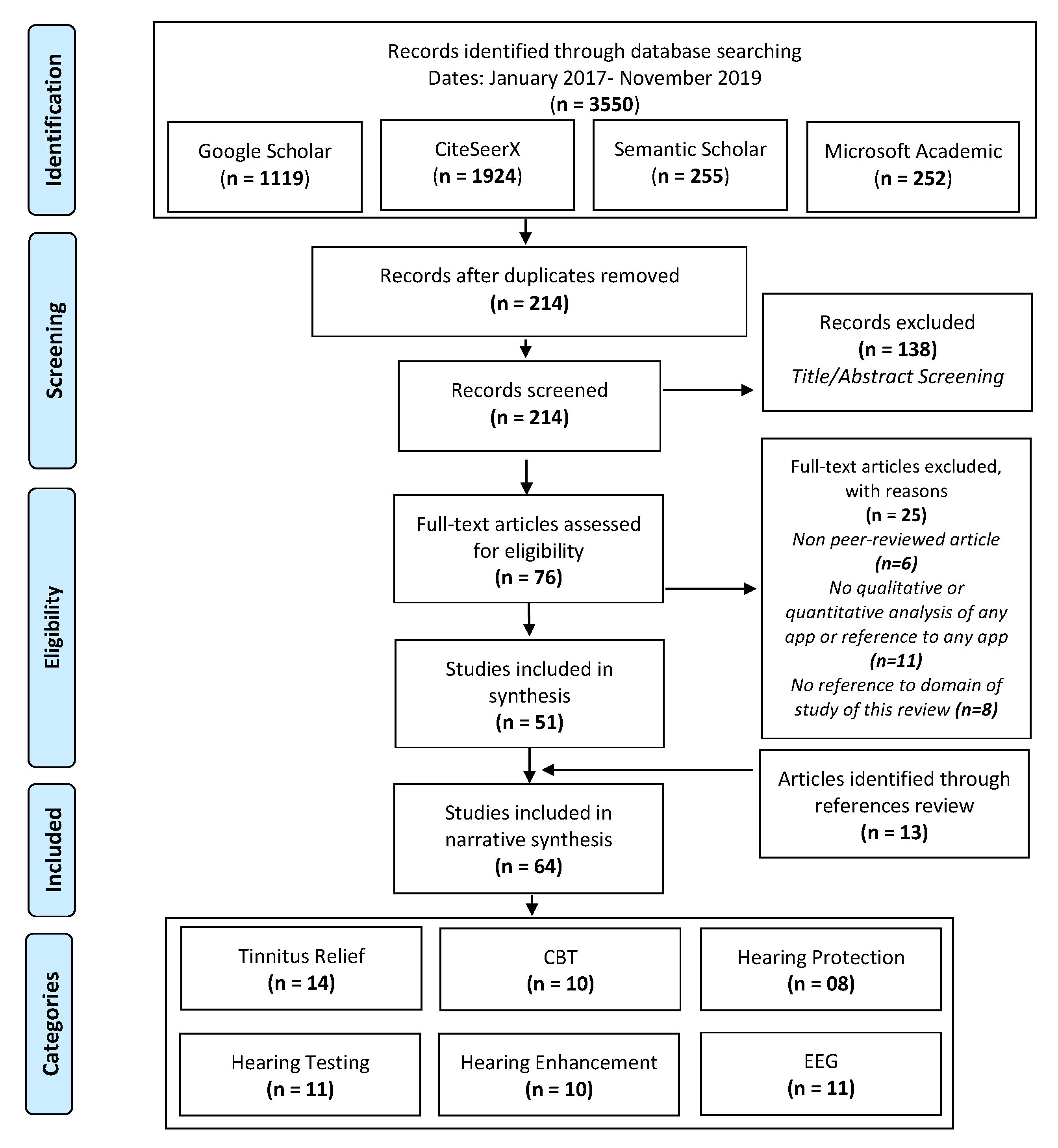

2. Review Design

2.1. Finding Relevant Literature

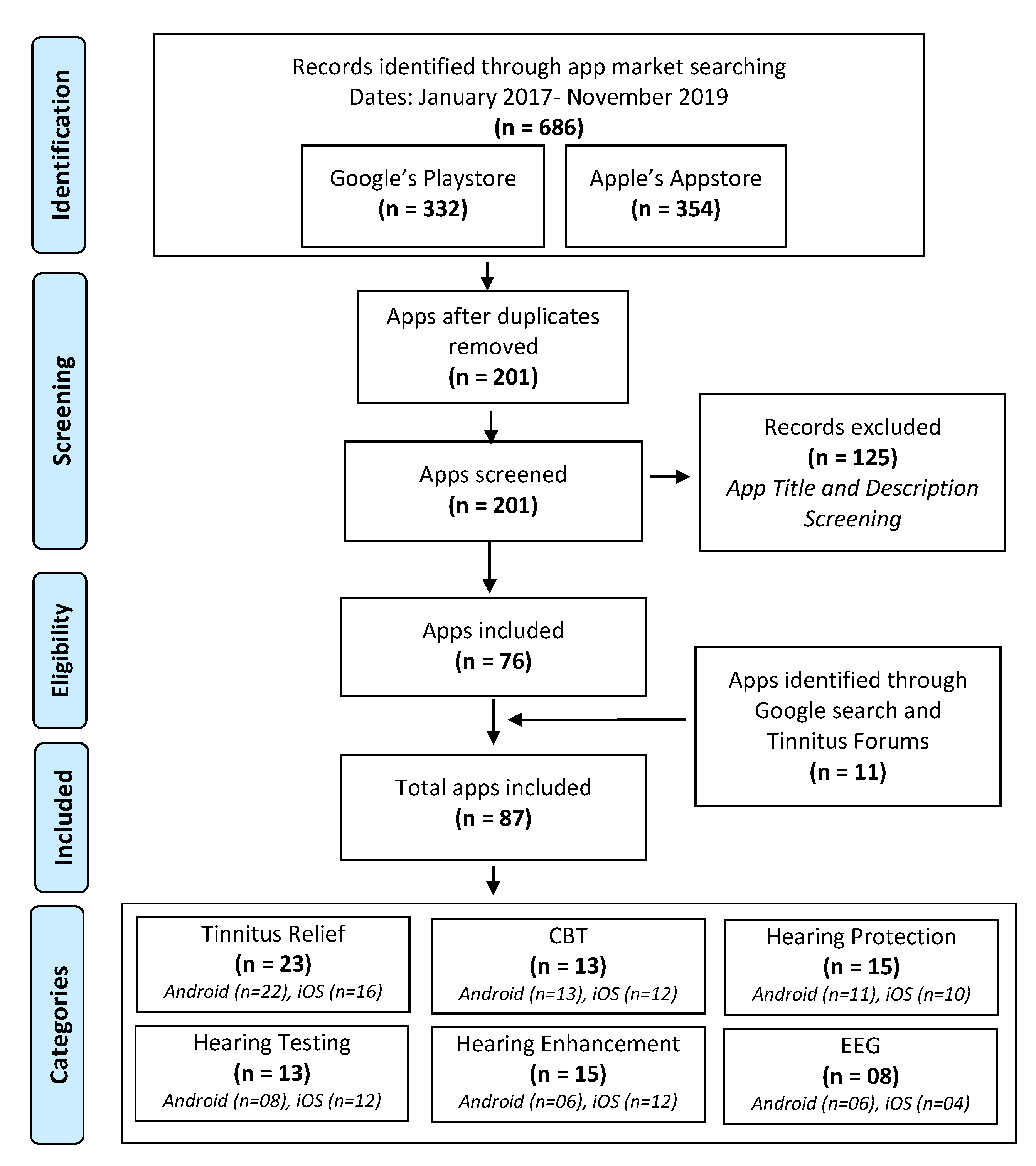

2.2. Finding Relevant Apps

2.3. Rationale Behind App Categorization

- Tinnitus Relief Different treatment modalities for the management of tinnitus symptoms exist, for instance, Tinnitus Retaining Therapy (TRT), Tinnitus Masking (TM), conventional drug delivery, and even brain stimulation—among them, TRT, TM using sound generators, and CBT as counseling are standard treatment procedures [1]. Most of the tinnitus relief apps that are generally published on app markets offer tinnitus masking, or sound therapies using different sound techniques like acoustic neuromodulation, notched sound, or amplitude modulation. Smartphones are capable of delivering acoustic and sound therapy reliably and accurately [39].

- CBT Although, the acoustic characteristics of tinnitus, particularly the subjective loudness of tinnitus is minimally affected by CBT [40], CBT has been pivotal for the treatment of tinnitus [41]. Since CBT and self-help therapies have been useful in dealing with stress and anxiety associated with tinnitus [42], we deem it important to be included in this review.

- Hearing protection Tinnitus is reported to be accompanied by hearing loss in more than 80% of cases [29]. Augmentation of tinnitus symptoms with increased noise exposures [43], and hearing loss being prevalent causal risk factor for tinnitus [44], it can be argued that hearing protection can lead to reduced odds for developing tinnitus, as well as support tinnitus patients in managing their symptoms.

- Hearing testing Since hearing loss is a commonly occurring phenomenon with tinnitus, we argue that apps for hearing testing are certainly linked to processes of tinnitus matching (for example, sensation levels for staircase procedures). Therefore, smartphone-based tinnitus matching may be a relevant feature for current or future sound therapies. Furthermore, in patients where the tinnitus is caused by hearing damage, using hearing aids (or even cochlear implants) can help to reduce tinnitus symptoms [45]. Therefore, we believe that it makes sense for the tinnitus patients to test their hearing and thus hearing testing apps are relevant for this review.

- Hearing enhancement Tinnitus and hearing loss has been reported to directly influence the quality of life of patients [44]. Apps for hearing enhancement could be useful to counteract tinnitus-related impairments of hearing functions in daily life like speech in noisy environments or cocktail-party situations, and directional hearing. Therefore, we consider our addition of hearing enhancement as rather straight forward.

- Smartphone-based EEG Despite the fact that tinnitus is traditionally considered only a problem of the inner ear, research using brain imaging has shown that the complexity of tinnitus goes beyond the auditory cortex into non-auditory brain areas [43,46]. Additionally, EEG allows the investigation of resting-state activity of the brain [43], and is widespread in tinnitus research [47,48,49]. With the growing interest in the development and significant technological advancements in mobile-based EEG systems and due to the fact of recent developments, it is possible to record EEG outside of a laboratory setting. Further, EEG is one approach of few to record the changes in brain activity, which corresponds to the perception of tinnitus [49]. That is why we considered smartphone-based electroencephalography (EEG) to be pertinent and included it in this review.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Tinnitus Relief Using Smartphones

3.2. Smartphone-Based CBT

3.3. Smartphone-Based Hearing Protection

3.4. Hearing Testing Using Smartphones

3.5. Smartphones-Based Hearing Enhancement

3.6. EEG Systems and Smartphones

4. Limitations, Future Work and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baguley, D.; McFerran, D.; Hall, D. Tinnitus. Lancet 2013, 382, 1600–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoor, A. Presbycusis values in relation to noise induced hearing loss. Int. Audiol. 1967, 6, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsson, L.; Hawkins, J. Sensory and neural degeneration with aging, as seen in microdissections of the human inner ear. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1972, 81, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuknecht, H.; Gacek, M. Cochlear pathology in presbycusis. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1993, 102, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardone, R.; Battista, P.; Panza, F.; Lozupone, M.; Griseta, C.; Castellana, F.; Capozzo, R.; Ruccia, M.; Resta, E.; Seripa, D.; et al. The Age-Related Central Auditory Processing Disorder: Silent Impairment of the Cognitive Ear. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panza, F.; Lozupone, M.; Sardone, R.; Battista, P.; Piccininni, M.; Dibello, V.; La Montagna, M.; Stallone, R.; Venezia, P.; Liguori, A.; et al. Sensorial frailty: Age-related hearing loss and the risk of cognitive impairment and dementia in later life. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2019, 10, 2040622318811000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlee, W.; Kleinjung, T.; Hiller, W.; Goebel, G.; Kolassa, I.T.; Langguth, B. Does tinnitus distress depend on age of onset? PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e27379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurek, B.; Szczepek, A.; Hebert, S. Stress and tinnitus. HNO 2015, 63, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastreboff, P.J.; Jastreboff, M.M. Tinnitus retraining therapy (TRT) as a method for treatment of tinnitus and hyperacusis patients. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2000, 11, 162–177. [Google Scholar]

- Probst, T.; Pryss, R.; Langguth, B.; Schlee, W. Emotion dynamics and tinnitus: Daily life data from the “TrackYourTinnitus” application. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimoto, K.; Aiba, S.; Takashima, R.; Suzuki, K.; Takekawa, H.; Watanabe, Y.; Tatsumoto, M.; Hirata, K. Influence of barometric pressure in patients with migraine headache. Intern. Med. 2011, 50, 1923–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, W.; Sarran, C.; Ronan, N.; Barrett, G.; Whinney, D.J.; Fleming, L.E.; Osborne, N.J.; Tyrrell, J. The weather and Meniere’s disease: A longitudinal analysis in the UK. Otol. Neurotol. 2017, 38, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staffen, W.; Biesinger, E.; Trinka, E.; Ladurner, G. The effect of lidocaine on chronic tinnitus: A quantitative cerebral perfusion study. Audiology 1999, 38, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volcy, M.; Sheftell, F.D.; Tepper, S.J.; Rapoport, A.M.; Bigal, M.E. Tinnitus in Migraine: An Allodynic Symptom Secondary to Abnormal Cortical Functioning? Headache J. Head Face Pain 2005, 45, 1083–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havia, M.; Kentala, E.; Pyykkö, I. Hearing loss and tinnitus in Meniere’s disease. Auris Nasus Larynx 2002, 29, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.J.; Chen, K. The relationship of tinnitus, hyperacusis, and hearing loss. Ear Nose Throat J. 2004, 83, 472–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schecklmann, M.; Landgrebe, M.; Langguth, B.; TRI Database Study Group. Phenotypic characteristics of hyperacusis in tinnitus. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herraiz, C.; Tapia, M.; Plaza, G. Tinnitus and Meniere’s disease: Characteristics and prognosis in a tinnitus clinic sample. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. Head Neck 2006, 263, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H. Seasonal affective disorder in patients with chronic tinnitus. Laryngoscope 2016, 126, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlee, W.; Pryss, R.C.; Probst, T.; Schobel, J.; Bachmeier, A.; Reichert, M.; Langguth, B. Measuring the moment-to-moment variability of tinnitus: The TrackYourTinnitus smart phone app. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2016, 8, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naslund, J.A.; Aschbrenner, K.A.; Barre, L.K.; Bartels, S.J. Feasibility of popular m-health technologies for activity tracking among individuals with serious mental illness. Telemed. e-Health 2015, 21, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, E.C.; Verhagen, T.; Noordzij, M.L. Health empowerment through activity trackers: An empirical smart wristband study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 62, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buijink, A.W.G.; Visser, B.J.; Marshall, L. Medical apps for smartphones: Lack of evidence undermines quality and safety. BMJ Evid.-Based Med. 2013, 18, 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Freeman, B.; Li, M. Can mobile phone apps influence people’s health behavior change? An evidence review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdi, M.; Mühlmeier, G.; Agrawal, K.; Pryss, R.; Reichert, M.; Hauck, F.J. Referenceable mobile crowdsensing architecture: A healthcare use case. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 134, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdi, M. Smart mobile crowdsensing for tinnitus research: Student research abstract. In Proceedings of the 34th ACM/SIGAPP Symposium on Applied Computing, Limassol, Cyprus, 8–12 April 2019; pp. 1220–1223. [Google Scholar]

- Mehdi, M.; Schwager, D.; Pryss, R.; Schlee, W.; Reichert, M.; Hauck, F.J. Towards Automated Smart Mobile Crowdsensing for Tinnitus Research. In Proceedings of the 32nd IEEE CBMS International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems, Cordoba, Spain, 5–7 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, T.P. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norena, A.; Micheyl, C.; Chéry-Croze, S.; Collet, L. Psychoacoustic characterization of the tinnitus spectrum: Implications for the underlying mechanisms of tinnitus. Audiol. Neurotol. 2002, 7, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sereda, M.; Smith, S.; Newton, K.; Stockdale, D. Mobile Apps for Management of Tinnitus: Users’ Survey, Quality Assessment, and Content Analysis. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e10353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanov, S.R.; Hides, L.; Kavanagh, D.J.; Zelenko, O.; Tjondronegoro, D.; Mani, M. Mobile App Rating Scale: A New Tool for Assessing the Quality of Health Mobile Apps. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2015, 3, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalle, S.; Schlee, W.; Pryss, R.C.; Probst, T.; Reichert, M.; Langguth, B.; Spiliopoulou, M. Review of smart services for tinnitus self-help, diagnostics and treatments. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, J.H.; Marcus, D.K.; Barry, C.T. Evidence-based apps? A review of mental health mobile applications in a psychotherapy context. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2017, 48, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paglialonga, A.; Tognola, G.; Pinciroli, F. Apps for hearing science and care. Am. J. Audiol. 2015, 24, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, T.; Pallawela, D. Validated smartphone-based apps for ear and hearing assessments: A review. JMIR Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2016, 3, e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; She, D.; Qian, Z. Android root and its providers: A double-edged sword. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, New York, NY, USA, 12–16 October 2015; pp. 1093–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Cederroth, C.R.; Gallus, S.; Hall, D.A.; Kleinjung, T.; Langguth, B.; Maruotti, A.; Meyer, M.; Norena, A.; Probst, T.; Pryss, R.C.; et al. Towards an Understanding of Tinnitus Heterogeneity. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederroth, C.R.; Canlon, B.; Langguth, B. Hearing loss and tinnitus—are funders and industry listening? Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauptmann, C.; Wegener, A.; Poppe, H.; Williams, M.; Popelka, G.; Tass, P.A. Validation of a mobile device for acoustic coordinated reset neuromodulation tinnitus therapy. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2016, 27, 720–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse, G. Evidence and evidence gaps in tinnitus therapy. GMS Curr. Top. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, H.J.; Park, M.K. Cognitive behavioral therapy for tinnitus: Evidence and efficacy. Korean J. Audiol. 2013, 17, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Devesa, P.; Waddell, A.; Perera, R.; Theodoulou, M. Cognitive behavioural therapy for tinnitus. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgoyhen, A.B.; Langguth, B.; De Ridder, D.; Vanneste, S. Tinnitus: Perspectives from human neuroimaging. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 632–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langguth, B.; Kreuzer, P.M.; Kleinjung, T.; De Ridder, D. Tinnitus: Causes and clinical management. Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12, 920–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, G.; Adjout, K.; Gallego, S.; Thai-Van, H.; Collet, L.; Norena, A. Effects of hearing aid fitting on the perceptual characteristics of tinnitus. Hear. Res. 2009, 254, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastreboff, P.J. Phantom auditory perception (tinnitus): Mechanisms of generation and perception. Neurosci. Res. 1990, 8, 221–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güntensperger, D.; Thüring, C.; Meyer, M.; Neff, P.; Kleinjung, T. Neurofeedback for tinnitus treatment–review and current concepts. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohrmann, K.; Weisz, N.; Schlee, W.; Hartmann, T.; Elbert, T. Neurofeedback for treating tinnitus. Prog. Brain Res. 2007, 166, 473–554. [Google Scholar]

- Adjamian, P. The application of electro-and magneto-encephalography in tinnitus research–methods and interpretations. Front. Neurol. 2014, 5, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryss, R.; Schlee, W.; Langguth, B.; Reichert, M. Mobile crowdsensing services for tinnitus assessment and patient feedback. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on AI & Mobile Services (AIMS), Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 June 2017; pp. 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hiller, W.; Goebel, G. Rapid assessment of tinnitus-related psychological distress using the Mini-TQ. Int. J. Audiol. 2004, 43, 600–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamchic, I.; Langguth, B.; Hauptmann, C.; Tass, P.A. Psychometric evaluation of visual analog scale for the assessment of chronic tinnitus. Am. J. Audiol. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.A.; Thielman, E.; Zaugg, T.; Kaelin, C.; Choma, C.; Chang, B.; Hahn, S.; Fuller, B. Development and field testing of a smartphone “App” for tinnitus management. Int. J. Audiol. 2017, 56, 784–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pablo, C.; Alberto, E.; Angelo, T.; Pierpaolo, V. An App Supporting the Self-management of Tinnitus. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Practical Applications of Computational Biology & Bioinformatics, Porto, Portugal, 21–23 June 2017; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F., III; Monk, T.H.; Hoch, C.C.; Yeager, A.L.; Kupfer, D.J. Quantification of subjective sleep quality in healthy elderly men and women using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Sleep 1991, 14, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khalfa, S.; Dubal, S.; Veuillet, E.; Perez-Diaz, F.; Jouvent, R.; Collet, L. Psychometric normalization of a hyperacusis questionnaire. Orl 2002, 64, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, C.W.; Jacobson, G.P.; Spitzer, J.B. Development of the tinnitus handicap inventory. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1996, 122, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, T.; Pryss, R.; Langguth, B.; Schlee, W. Emotional states as mediators between tinnitus loudness and tinnitus distress in daily life: Results from the “TrackYourTinnitus” application. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, T.; Pryss, R.C.; Langguth, B.; Spiliopoulou, M.; Landgrebe, M.; Vesala, M.; Harrison, S.; Schobel, J.; Reichert, M.; Stach, M.; et al. Outpatient tinnitus clinic, self-help web platform, or mobile application to recruit tinnitus study samples? Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryss, R.; Probst, T.; Schlee, W.; Schobel, J.; Langguth, B.; Neff, P.; Spiliopoulou, M.; Reichert, M. Prospective crowdsensing versus retrospective ratings of tinnitus variability and tinnitus–stress associations based on the TrackYourTinnitus mobile platform. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. 2018, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniandi, L.P.; Schlee, W.; Pryss, R.; Reichert, M.; Schobel, J.; Kraft, R.; Spiliopoulou, M. Finding tinnitus patients with similar evolution of their Ecological Momentary Assessments. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 31st International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (CBMS), Karlstad, Sweden, 18–21 June 2018; pp. 112–117. [Google Scholar]

- Piskosz, M. ReSound Relief: A Comprehensive Tool for Tinnitus Management. Audiol. Online 2017, 1–11. Available online: https://www.audiologyonline.com/articles/resound-relief-comprehensive-tool-for-20353 (accessed on 19 March 2020).

- Hesse, G. Smartphone app-supported approaches to tinnitus therapy. HNO 2018, 66, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Chang, M.Y.; Hong, M.; Yoo, S.G.; Oh, D.; Park, M.K. Tinnitus therapy using tailor-made notched music delivered via a smartphone application and Ginko combined treatment: A pilot study. Auris Nasus Larynx 2017, 44, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryss, R.; Reichert, M.; Schlee, W.; Spiliopoulou, M.; Langguth, B.; Probst, T. Differences between android and ios users of the trackyourtinnitus mobile crowdsensing mhealth platform. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 31st International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (CBMS), Karlstad, Sweden, 18–21 June 2018; pp. 411–416. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, S.K.; Viirre, E.S.; Bailey, K.A.; Kindermann, S.; Minassian, A.L.; Goldin, P.R.; Pedrelli, P.; Harris, J.P.; McQuaid, J.R. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavior therapy for tinnitus. Int. Tinnitus J. 2008, 14, 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Kaldo, V.; Levin, S.; Widarsson, J.; Buhrman, M.; Larsen, H.C.; Andersson, G. Internet versus group cognitive-behavioral treatment of distress associated with tinnitus: A randomized controlled trial. Behav. Ther. 2008, 39, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, G.; Strömgren, T.; Ström, L.; Lyttkens, L. Randomized controlled trial of internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for distress associated with tinnitus. Psychosom. Med. 2002, 64, 810–816. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kaldo-Sandstrom, V.; Larsen, H.C.; Andersson, G. Internet-Based Cognitive—Behavioral Self-Help Treatment of Tinnitus. Am. J. Audiol. 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langguth, B.; Landgrebe, M.; Kleinjung, T.; Sand, G.P.; Hajak, G. Tinnitus and depression. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 12, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattyn, T.; Van Den Eede, F.; Vanneste, S.; Cassiers, L.; Veltman, D.; Van De Heyning, P.; Sabbe, B. Tinnitus and anxiety disorders: A review. Hear. Res. 2016, 333, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husain, F.T.; Zimmerman, B.; Tai, Y.; Finnegan, M.K.; Kay, E.; Khan, F.; Menard, C.; Gobin, R.L. Assessing mindfulness-based cognitive therapy intervention for tinnitus using behavioural measures and structural MRI: A pilot study. Int. J. Audiol. 2019, 58, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, K.M.; Evans, S.S.; Bielko, S.L.; Rohlman, D.S. Efficacy of technology-based interventions to increase the use of hearing protections among adolescent farmworkers. Int. J. Audiol. 2018, 57, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, K.L.; Welles, R.; Zurek, P. Development of the Warfighter’s Hearing Health Instructional (WHHIP) Primer App. Mil. Med. 2018, 183, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.M.; Bielko, S.L.; McCullagh, M.C. Efficacy of hearing conservation education programs for youth and young adults: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Themann, C.L.; Kardous, C.A.; Beamer, B.R.; Morata, T.C. ‘Internet of Ears’ and Hearables for Hearing Loss Prevention. Hear. J. 2019, 72, 32–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B. Improved Methods for Evaluating Noise Exposure and Hearing Loss. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, K.; Kardous, C.A.; Shaw, P.B.; Kim, B.; Mechling, J.; Azman, A.S. The potential use of a NIOSH sound level meter smart device application in mining operations. Noise Control. Eng. J. 2019, 67, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Kozin, E.D.; Naunheim, M.R.; Barber, S.R.; Wong, K.; Katz, L.W.; Otero, T.M.; Stefanov-Wagner, I.J.; Remenschneider, A.K. Cycling exercise classes may be bad for your (hearing) health. Laryngoscope 2017, 127, 1873–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura, R.; Mallet, V.; Issarny, V.; Raverdy, P.G.; Rebhi, F. Evaluation and calibration of mobile phones for noise monitoring application. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2017, 142, 3084–3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.C.; Cheng, Y.F.; Lai, Y.H.; Tsao, Y.; Tu, T.Y.; Young, S.T.; Chen, T.S.; Chung, Y.F.; Lai, F.; Liao, W.H. A Mobile Phone–Based Approach for Hearing Screening of School-Age Children: Cross-Sectional Validation Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e12033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yimtae, K.; Israsena, P.; Thanawirattananit, P.; Seesutas, S.; Saibua, S.; Kasemsiri, P.; Noymai, A.; Soonrach, T. A Tablet-Based Mobile Hearing Screening System for Preschoolers: Design and Validation Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018, 6, e186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousuf Hussein, S.; Swanepoel, D.W.; Mahomed, F.; Biagio de Jager, L. Community-based hearing screening for young children using an mHealth service-delivery model. Glob. Health Action 2018, 11, 1467077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saliba, J.; Al-Reefi, M.; Carriere, J.S.; Verma, N.; Provencal, C.; Rappaport, J.M. Accuracy of mobile-based audiometry in the evaluation of hearing loss in quiet and noisy environments. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2017, 156, 706–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louw, C.; Eikelboom, R.H.; Myburgh, H.C. Smartphone-based hearing screening at primary health care clinics. Ear Hear. 2017, 38, e93–e100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, R.K.; Ghanad, I.; Kanumuri, V.; Herrmann, B.; Kozin, E.D.; Remenschneider, A.K. Mobile Hearing Testing Applications and the Diagnosis of Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss: A Cautionary Tale. Otol. Neurotol. 2018, 39, e1–e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brittz, M.; Heinze, B.; Mahomed-Asmail, F.; Swanepoel, D.W.; Stoltz, A. Monitoring Hearing in an Infectious Disease Clinic with mHealth Technologies. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2019, 30, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Tonder, J.; Swanepoel, D.W.; Mahomed-Asmail, F.; Myburgh, H.; Eikelboom, R.H. Automated smartphone threshold audiometry: Validity and time efficiency. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2017, 28, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornman, M.E. Validation of hearTest Smartphone Application for Extended High Frequency Hearing Thresholds. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Masalski, M.; Grysiński, T.; Kręcicki, T. Hearing Tests Based on Biologically Calibrated Mobile Devices: Comparison With Pure-Tone Audiometry. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018, 6, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickens, A.W.; Robertson, L.D.; Smith, M.L.; Zheng, Q.; Song, S. Headphone Evaluation for App-Based Automated Mobile Hearing Screening. Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2018, 22, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paglialonga, A.; Nielsen, A.C.; Ingo, E.; Barr, C.; Laplante-Levesque, A. eHealth and the hearing aid adult patient journey: A state-of-the-art review. Biomed. Eng. Online 2018, 17, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Tiwari, N.; Pandey, P.C. Implementation of Digital Hearing Aid as a Smartphone Application. Proc. Interspeech 2018, 1175–1179. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, T.A.; Sehgal, A.; Kehtarnavaz, N. Integrating Signal Processing Modules of Hearing Aids into a Real-Time Smartphone App. In Proceedings of the 2018 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Honolulu, HI, USA, 18-21 July 2018; pp. 2837–2840. [Google Scholar]

- Klasen, T.J.; Van den Bogaert, T.; Moonen, M.; Wouters, J. Binaural noise reduction algorithms for hearing aids that preserve interaural time delay cues. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2007, 55, 1579–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saki, F.; Kehtarnavaz, N. Online frame-based clustering with unknown number of clusters. Pattern Recognit. 2016, 57, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Sehgal, A.; Kehtarnavaz, N. Low-latency smartphone app for real-time noise reduction of noisy speech signals. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 26th International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE), Edinburgh, UK, 19–21 June 2017; pp. 1280–1284. [Google Scholar]

- Alamdari, N.; Yaraganalu, S.; Kehtarnavaz, N. A Real-Time Personalized Noise Reduction Smartphone App for Hearing Enhancement. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Signal Processing in Medicine and Biology Symposium (SPMB), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1 December 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, A.; Williams, R.; Livingston, E.; Futscher, C. Review of Auditory Training Mobile Apps for Adults With Hearing Loss. Perspect. Asha Spec. Interest Groups 2018, 3, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. Mobile application development for improving auditory memory skills of children with hearing impairment. Audiol. Speech Res. 2017, 13, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarenoe, R.; Ledin, T. Quality of life in patients with tinnitus and sensorineural hearing loss. B-ent 2014, 10, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Folmer, R.L.; Martin, W.H.; Shi, Y.; Edlefsen, L.L. Lifestyle changes for tinnitus self-management. Tinnitus Treat. Clin. Protoc. 2006, 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Trotter, M.; Donaldson, I. Hearing aids and tinnitus therapy: A 25-year experience. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2008, 122, 1052–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kochkin, S.; Tyler, R. Tinnitus treatment and the effectiveness of hearing aids: Hearing care professional perceptions. Hear. Rev 2008, 15, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Norena, A.; Eggermont, J. Changes in spontaneous neural activity immediately after an acoustic trauma: Implications for neural correlates of tinnitus. Hear. Res. 2003, 183, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güntensperger, D.; Thüring, C.; Kleinjung, T.; Neff, P.; Meyer, M. Investigating the Efficacy of an Individualized Alpha/Delta Neurofeedback Protocol in the Treatment of Chronic Tinnitus. Neural Plast. 2019, 2019, 3540898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thibault, R.T.; Raz, A. The psychology of neurofeedback: Clinical intervention even if applied placebo. Am. Psychol. 2017, 72, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, L.D.; Chen, C.Y.; Wang, I.J.; Chen, S.F.; Li, S.Y.; Chen, B.W.; Chang, J.Y.; Lin, C.T. Gaming control using a wearable and wireless EEG-based brain-computer interface device with novel dry foam-based sensors. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2012, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.L.; Fairweather, M.M.; Donaldson, D.I. Making the case for mobile cognition: EEG and sports performance. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2015, 52, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.Y.; Chang, D.W.; Liu, Y.D.; Liu, C.W.; Young, C.P.; Liang, S.F.; Shaw, F.Z. Portable wireless neurofeedback system of EEG alpha rhythm enhances memory. Biomed. Eng. Online 2017, 16, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antle, A.N.; Chesick, L.; Mclaren, E.S. Opening up the Design Space of Neurofeedback Brain–Computer Interfaces for Children. Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 2018, 24, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, E.D.; Lim, A.S.; Leung, E.C.; Cole, A.J.; Lam, A.D.; Eloyan, A.; Nirola, D.K.; Tshering, L.; Thibert, R.; Garcia, R.Z.; et al. Validation of a smartphone-based EEG among people with epilepsy: A prospective study. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stopczynski, A.; Stahlhut, C.; Larsen, J.E.; Petersen, M.K.; Hansen, L.K. The smartphone brain scanner: A portable real-time neuroimaging system. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau-Zhu, A.; Lau, M.P.; McLoughlin, G. Mobile EEG in Research on Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Opportunities and Challenges. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2019, 36, 100635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlee, W.; Hall, D.A.; Canlon, B.; Cima, R.F.; de Kleine, E.; Hauck, F.; Huber, A.; Gallus, S.; Kleinjung, T.; Kypraios, T.; et al. Innovations in doctoral training and research on tinnitus: The European School on Interdisciplinary Tinnitus Research (ESIT) Perspective. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 9, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| App Name | Description | Platform | Users | Rating | Update | Pricing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H& T Sound Therapy | Noise Player (pink noise, white noise or brown noise) for masking tinnitus | Android | 10K+ | Oct-19 | Free | |

| Kalmeda mynoise* | Offers medically-based, individual tinnitus therapy | Android | 1000+ | Jul-19 | Free(I) | |

| iOS | - | Jul-19 | Free(I) | |||

| myNoise* | Controlling tinnitus via combination of different sounds and noises | Android | 100K+ | Mar-18 | Free(I) | |

| iOS | - | Apr-19 | Free(I) | |||

| Oticon Tinnitus Sound* | Offers different sound types to control tinnitus | Android | 100K+ | Feb-19 | Free | |

| iOS | - | Feb-19 | Free | |||

| Relax Melodies* | Sleep assisting app that combines sounds and melodies | Android | 10M+ | May-19 | Free(I, A) | |

| iOS | - | May-19 | Free(I) | |||

| Relax Noise 3* | Masking tinnitus by using red, white, or pink noise | Android | 100K+ | Mar-15 | Free | |

| SimplyNoise* | Controlling and managing stress and tinnitus using white, and brown noises | Android | 50K+ | Jun-12 | Free | |

| iOS | - | May-18 | Free(I) | |||

| Starkey Relax* | Tinnitus masking, self-management, and education app | Android | 10K+ | Oct-17 | Free | |

| iOS | - | Oct-17 | Free | |||

| StopTinnitus* | Masking tinnitus using customised tones | Android | 100+ | Jan-15 | 7.95 | |

| iOS | - | Jan-15 | 8.03 | |||

| Tinnitracks* | Controlling and managing tinnitus by filtering out music for sound therapy | Android | 10K+ | Apr-19 | Free(I) | |

| iOS | - | Feb-19 | Free(I) | |||

| Tinnitus Balance App* | Controlling annoying tinnitus using customised sounds or music | Android | 50K+ | Mar-16 | Free | |

| iOS | - | Mar-19 | Free | |||

| Tinnitus Help* | Tinnitus masking using natural sounds or music | Android | 500+ | Nov-15 | 9.90 | |

| iOS | - | Jan-19 | 17.99 | |||

| Tinnitus Notch | Provided custom tailored notch therapy for tinnitus relief | Android | 1000+ | Sep-16 | Free(I) | |

| Tinnitus Peace | Offers melodies to match the frequency of tinnitus to reduce its effects | Android | 5K+ | Nov-15 | Free | |

| TinnitusPlay | Tinnitus masking using different sound techniques | iOS | - | Dec-19 | Free | |

| Tinnitus Relief* | Controlling tinnitus using information on different relaxation exercises | Android | 1000+ | Dec-13 | 2.99 | |

| Tinnitus Sound Therapy | Sound/Acoustic therapy for masking tinnitus | Android | 10K+ | Jun-19 | Free | |

| Tinnitus Therapy (Lite)* | Avoiding tinnitus with sound masking and therapy | Android | 500+ | Feb-19 | 6.49 | |

| iOS | - | Mar-19 | 5.36 | |||

| Tonal Tinnitus Therapy* | Helps to mitigate symptoms of tonal tinnitus based on acoustic neuromodulation | Android | 10K+ | Jul-18 | Free(I) | |

| Track Your Tinnitus* | Managing tinnitus by tracking tinnitus patterns in daily activity | Android | 1000+ | Oct-18 | Free | |

| iOS | - | Jun-17 | Free | |||

| Whist* | Controlling tinnitus using sounds with adjusted volume, pitch etc. | Android | 1000+ | Mar-17 | 2.18 | |

| iOS | - | Jan-19 | 1.78 | |||

| White Noise (Lite)* | Masking and Controlling tinnitus using environmental sounds | Android | 5K+ | Sep-18 | 3.19 | |

| iOS | - | Apr-19 | 2.67 | |||

| Widex Zen* | Avoiding tinnitus using relaxing zen sounds, and exercises to manage tinnitus | Android | 10K+ | May-17 | Free | |

| iOS | - | Nov-17 | Free |

| App Name | Description | Platform | Users | Rating | Update | Pricing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beltone Tinnitus Calmer* | Combination of relaxation exercise and sound therapy to avoid tinnitus | Android | 1000+ | Sep-19 | Free(I) | |

| iOS | - | Sep-19 | Free(I) | |||

| CBT Companion | Employs visual tools to learn and practice CBT techniques | Android | 50K+ | Feb-19 | Free(I) | |

| iOS | - | Feb-19 | Free | |||

| Diapason for tinnitus* | Game-based digital therapeutic providing app for tinnitus relief | Android | 5K+ | May-19 | Free(I) | |

| iOS | - | - | May-19 | Free(I) | ||

| MindShift CBT* | CBT tools to manage and control anxiety | Android | 100K+ | Oct-19 | Free | |

| iOS | - | Oct-19 | Free | |||

| Moodfit—Stress and Anxiety | Stress and Anxiety management and tracking, and offers CBT exercises | Android | 5K+ | Aug-19 | Free | |

| Quirk CBT | Self-help CBT companion based on ‘three column technique’ | Android | 10K+ | Jul-19 | Free(I) | |

| iOS | - | Sep-19 | Free(I) | |||

| ReSound Relief* | Avoiding tinnitus using combination of sound therapy and relaxation exercise | Android | 100K+ | Feb-19 | Free(I) | |

| iOS | - | Jan-19 | Free(I) | |||

| Sanvello—Stress and Anxiety Help | Audio and Video CBT exercises, Anxiety tracking and management | Android | 1M+ | Feb-19 | Free(I) | |

| iOS | - | Nov-19 | Free(I) | |||

| Stress and Anxiety Companion | CBT based visual exercises to manage stress and anxiety | Android | 10K+ | Jul-19 | Free(I) | |

| iOS | - | Jun-19 | Free(I) | |||

| What’s Up? A Mental Health App | Offers CBT and ACT methods to manage stress, anxiety as well as depression | Android | 50K+ | Jun-19 | Free(I) | |

| iOS | - | Dec-16 | Free(I) | |||

| Woebot - Your Self-Care Expert* | A chatbot for guided CBT to manage stress and anxiety | Android | 100K+ | Nov-19 | Free | |

| iOS | - | Nov-19 | Free | |||

| Wysa: Mental Health Therapy* | A chatbot offering CBT and DBT techniques | Android | 1M+ | Nov-19 | Free(I) | |

| iOS | - | Dec-19 | Free(I) | |||

| Youper - Emotional Health* | A chatbot based on CBT and ACT techniques, monitoring and tracking mood changes | Android | 1M+ | Dec-19 | Free(I) | |

| iOS | - | Dec-19 | Free(I) |

| App Name | Description | Platform | Users | Rating | Update | Pricing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decibel X* | iOS equivalent of SPL Meter and Sound Meter | iOS | - | Jan-19 | Free(I) | |

| dbTrack | Uses earphones to measure sound exposure inside the ear canal | Android | 10+ | - | May-19 | Free |

| Hearangel | Monitors music levels, notifies extreme and dangerous sound levels | Android | 1000+ | Sep-18 | Free | |

| iHEARu Here* | Crowdsourcing tool to report noise levels and find low sound exposure places | Android | 10000+ | Aug-18 | Free | |

| iOS | - | - | Sep-18 | Free | ||

| NIOSH Sound Level Meter* | Notifies user of current sound environment | iOS | - | May-19 | Free | |

| Noise Control | Measures surrounding sounds, allows recording and playback | Android | - | - | Sep-12 | Free |

| iOS | - | - | May-15 | Free | ||

| NoiseCapture* | Evaluates noise environment and reports exposure | Android | 100K+ | Mar-19 | Free | |

| NoiSee* | Offers ANSI- or IEC-compliant sound level monitoring | iOS | - | Jan-19 | 0.89€(I) | |

| NoiseScore* | Documents and visualizes environmental soundscape of users | Android | 100+ | Apr-18 | Free | |

| iOS | - | Apr-18 | Free | |||

| Soundcheck* | Identifies overexposing sounds and recommends hearing protection | Android | 10K+ | Jun-15 | Free | |

| iOS | - | Jul-19 | Free | |||

| Sound Meter* | Measures loudness of the environment, reference sound comparison | Android | 10M+ | Apr-19 | Free(A) | |

| Sound Meter - SPL Meter* | Sound Pressure Level (SPL) meter, reference sound comparison | Android | 50K+ | May-19 | Free(A) | |

| SoundPrint* | Crowdsourcing-based approach to find quiet places | Android | 1000+ | Apr-19 | Free | |

| iOS | - | Apr-19 | Free | |||

| SPLnFFT Noise Meter* | SPL with frequency analyzer, signal generator, dosimeter, etc. | iOS | - | Oct-18 | 3.59(I) | |

| Too Noisy Pro* | Monitors noise levels in a closed environment, e.g., in classroom | Android | 1000+ | Feb-16 | 5.49€ | |

| iOS | - | Jan-17 | 4.46€ |

| App Name | Description | Platform | Users | Rating | Update | Pricing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Audicus Hearing Test* | Quick hearing test at different frequencies | iOS | - | Oct-18 | Free | |

| Better Hearing | Hearing test to identify inaudible frequencies | iOS | - | Sep-12 | Free(I) | |

| Hearing Test* | Hearing test in normal and noisy environments shows results in audiogram | Android | 1M+ | Dec-16 | Free | |

| iOS | - | Aug-13 | Free(I) | |||

| Hearing Test Pro* | Paid version of Hearing Test | Android | 1K+ | Dec-16 | 3.58€ | |

| hearWHO* | Hearing test using headphones from WHO | Android | 10K+ | Mar-16 | Free | |

| iOS | - | May-13 | Free | |||

| Jacoti Hearing Center* | Helps in tracking hearing and provides results using DuoToneTM technology | iOS | - | Mar-19 | Free | |

| Mimi Hearing Test* | Determines hearing age based on hearing test | Android | 10K+ | Sep-18 | Free | |

| iOS | - | Jan-19 | Free | |||

| Signia Hearing Test* | Hearing test to identify words in background noise | Android | 10K+ | Nov-18 | Free | |

| iOS | - | Jan-19 | Free | |||

| Sound Scouts* | A game-based hearing test for children | Android | 1K+ | Mar-19 | Free | |

| iOS | - | Mar-19 | Free | |||

| Soundcheck* | Screens hearing and shows results in easy to read format | Android | 10K+ | Jun-15 | Free | |

| iOS | - | Jul-15 | Free | |||

| Tone Generator | Compares hearing with friends and family using customised frequency tones | iOS | - | Sep-16 | Free(I) | |

| Track Your Hearing* | Helps in monitoring and keeping track of hearing loss | Android | 50+ | Feb-18 | Free | |

| iOS | - | - | Feb-15 | Free | ||

| uHear* | Hearing test in normal and noisy environments | iOS | - | Oct-15 | Free |

| App Name | Description | Platform | Users | Rating | Update | Pricing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUD-1* | Improves sound clarity using signal processing techniques | iOS | - | Nov-15 | 6.26€ | |

| BioAid* | Offers different amplifications for a personalized selection | iOS | - | Feb-15 | Free | |

| Ear Agent | Sound enhancements using headphones | Android | 5M+ | Feb-19 | Free(I,A) | |

| Ear Booster | Sound amplification using headphones | Android | 100K+ | May-19 | Free(A) | |

| EarMachine* | Sound enhancing app by recording via microphones | iOS | - | Jan-17 | Free | |

| Ear Spy Pro | Noise reduction and sound enhancement | Android | 50K+ | Dec-18 | Free(A) | |

| EasyHearingAid | Hearing impairment assistance using different frequencies | iOS | - | Jan-15 | 0.89€ | |

| Hear | Hearing enhancement and noise control with auto personalized adjustments | iOS | - | Feb-18 | Free(I) | |

| Hear Coach | An app to increase and improve listening abilities using a game | Android | 5K+ | Mar-16 | Free | |

| iOS | - | Nov-19 | Free | |||

| Hearing Aid | An app to record conversation and remove background noise | iOS | - | - | Apr-19 | Free |

| Hearing Amplifier* | Enhances microphone input and outputs to headphones | iOS | - | Jan-19 | Free | |

| HearYouNow* | Sound amplifier for each ear | iOS | - | - | Free | |

| Jacoti ListenApp* | Enables apple ear phone to improve sound clarity | iOS | - | Mar-19 | Free | |

| Petralex Hearing Aid* | Incoming sound enhancement | Android | 100K+ | Apr-19 | Free(I) | |

| iOS | - | May-19 | Free(I) | |||

| uSound* | Amplifies sounds based on profile created using hearing tests | Android | 100K+ | Jan-19 | Free(I) | |

| iOS | - | Sep-18 | Free(I) |

| App Name | Description | EEG System | Platform | Users | Rating | Update | Pricing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BrainLog | Records brain activity, exports as .csv and stores in iCloud | Muse | iOS | - | Nov-15 | 1.09€ | |

| EEG 101 | Teaches users the basics of EEG while displaying their own brain data | Muse brain sensing headband | Android | 10K+ | May-18 | Free | |

| EEG Analyzer | Brain activity recorded and stored as .csv in Dropbox | MindWave by NeuroSky | Android | 10K+ | Aug-14 | 1.79€ | |

| eegID | Captures electrical activity of brain and stores in .csv | MindWave by NeuroSky | Android | 5K+ | Mar-14 | 1.79€ | |

| iBrainEEG2 | Brain activity analyzed in relation to functional connectivity network | Biosemi | Android | 1K+ | Mar-14 | Free | |

| Muse Monitor | Monitors EEG data and stores in .csv | Muse | Android | 5K+ | Jan-19 | 16.99€ | |

| Muse | iOS | - | Jan-19 | 13.40€ | |||

| MyEmotiv | Capture, save and playback recordings of brain activity in six “cognitive and emotional metrics” | EPOC | Android | 5K+ | Apr-19 | Free | |

| EPOC | iOS | - | Apr-19 | Free | |||

| Persyst Mobile | Mobile-phone–based EEG recorder | Persyst | iOS | - | Jul-18 | Free |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mehdi, M.; Riha, C.; Neff, P.; Dode, A.; Pryss, R.; Schlee, W.; Reichert, M.; Hauck, F.J. Smartphone Apps in the Context of Tinnitus: Systematic Review. Sensors 2020, 20, 1725. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20061725

Mehdi M, Riha C, Neff P, Dode A, Pryss R, Schlee W, Reichert M, Hauck FJ. Smartphone Apps in the Context of Tinnitus: Systematic Review. Sensors. 2020; 20(6):1725. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20061725

Chicago/Turabian StyleMehdi, Muntazir, Constanze Riha, Patrick Neff, Albi Dode, Rüdiger Pryss, Winfried Schlee, Manfred Reichert, and Franz J. Hauck. 2020. "Smartphone Apps in the Context of Tinnitus: Systematic Review" Sensors 20, no. 6: 1725. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20061725

APA StyleMehdi, M., Riha, C., Neff, P., Dode, A., Pryss, R., Schlee, W., Reichert, M., & Hauck, F. J. (2020). Smartphone Apps in the Context of Tinnitus: Systematic Review. Sensors, 20(6), 1725. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20061725