Palladium-Doped Tin Oxide Nanosensor for the Detection of the Air Pollutant Carbon Monoxide Gas

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Methods

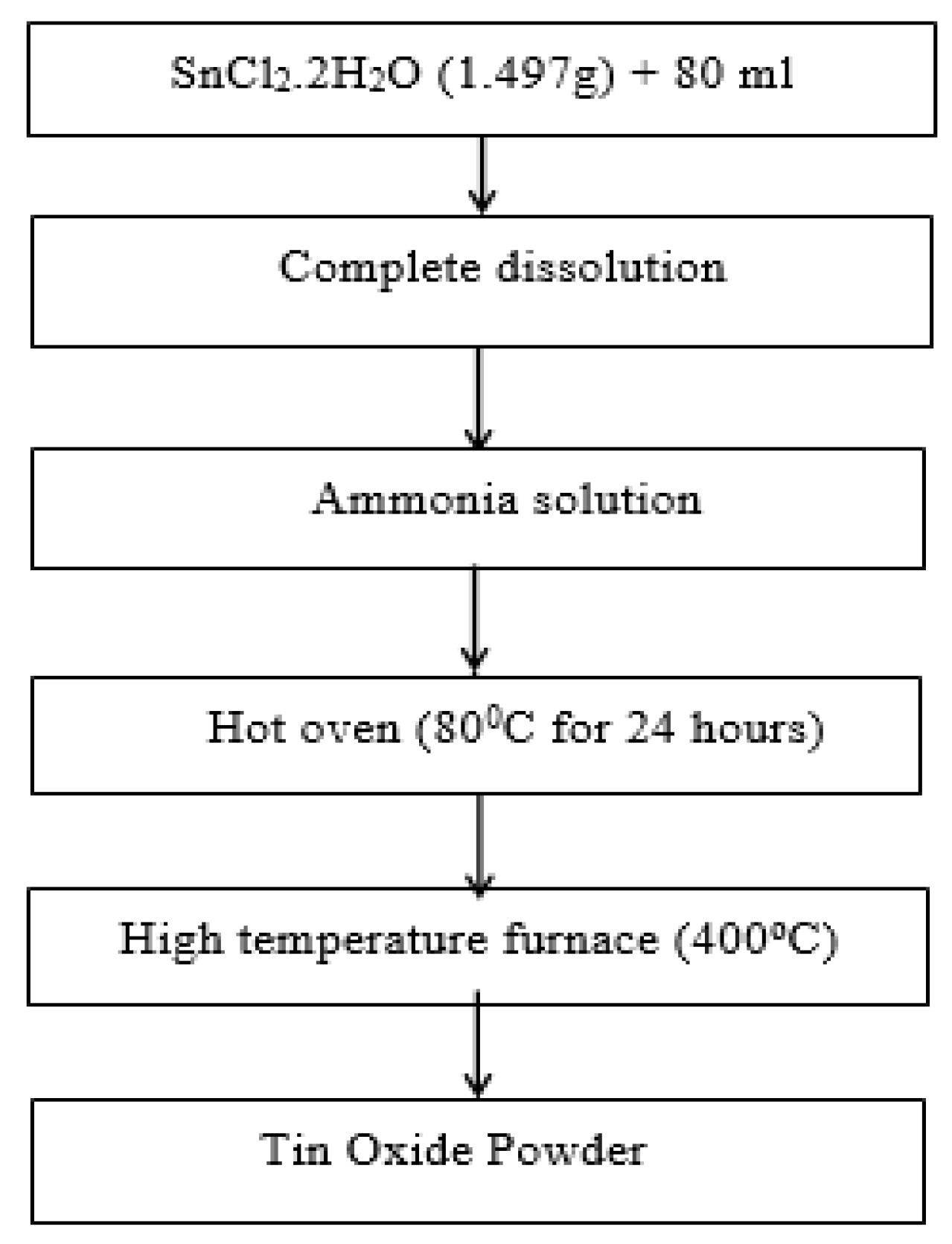

2.1. Synthesis of SnO2

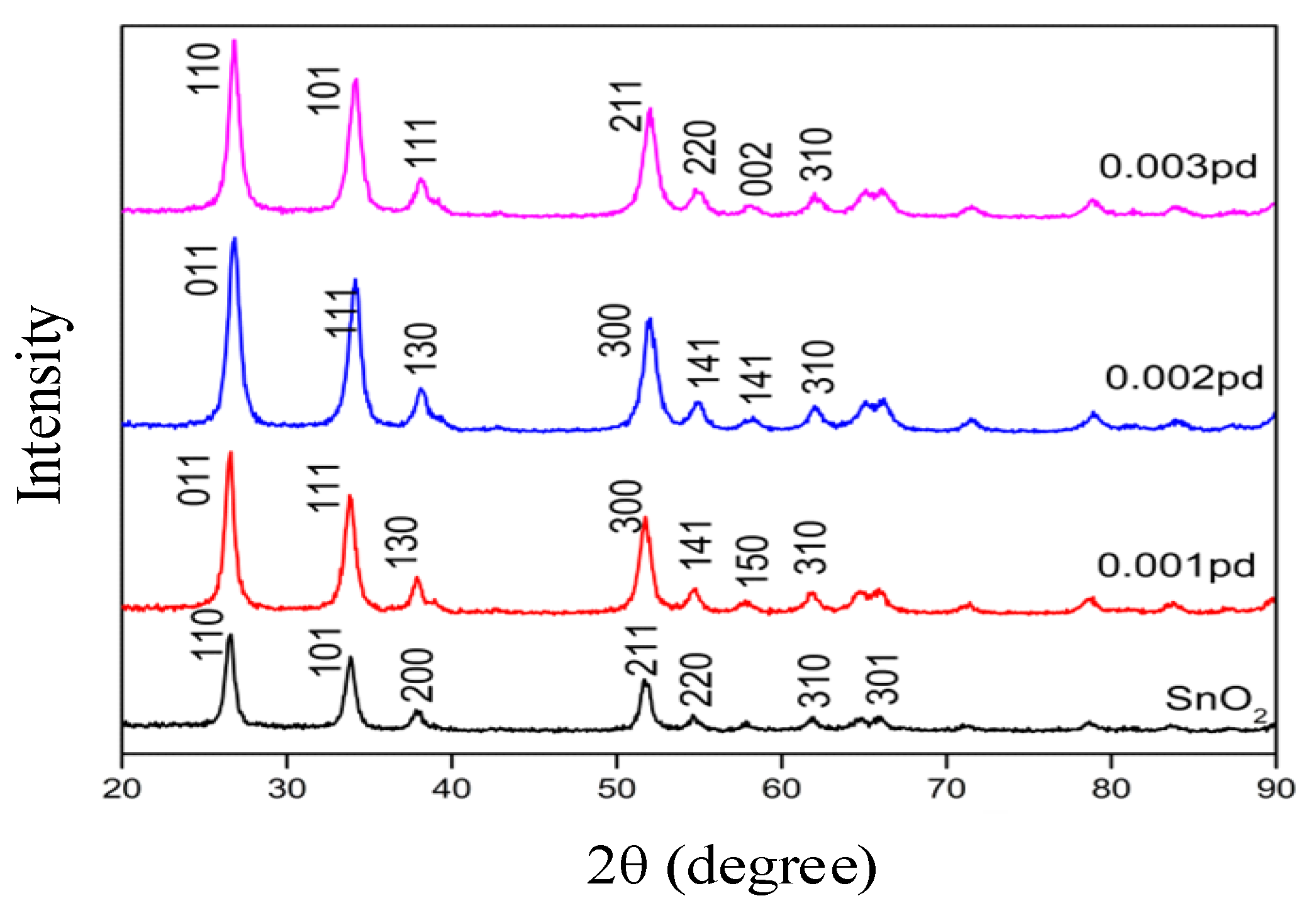

2.2. X-ray Diffraction

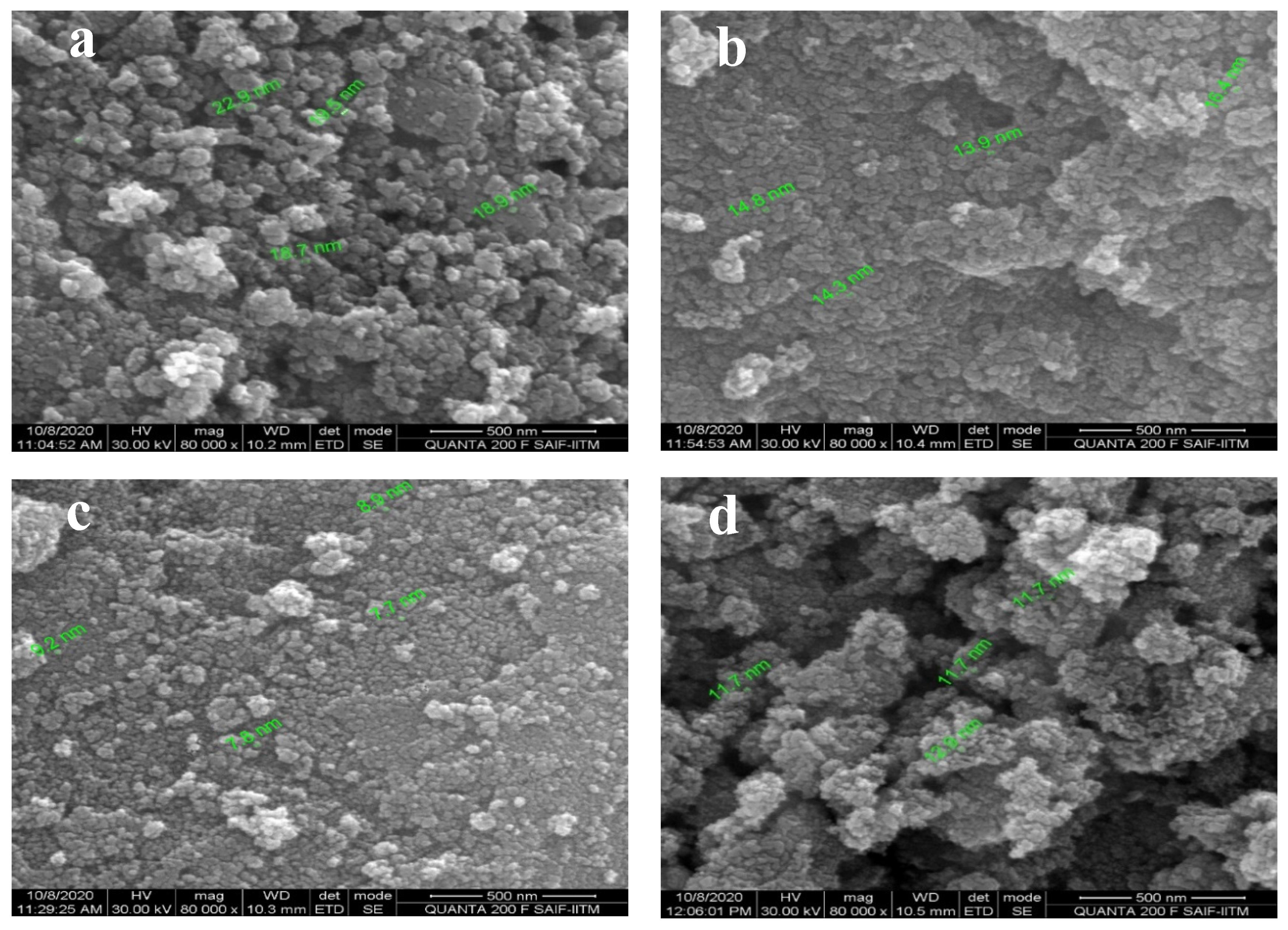

2.3. Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy

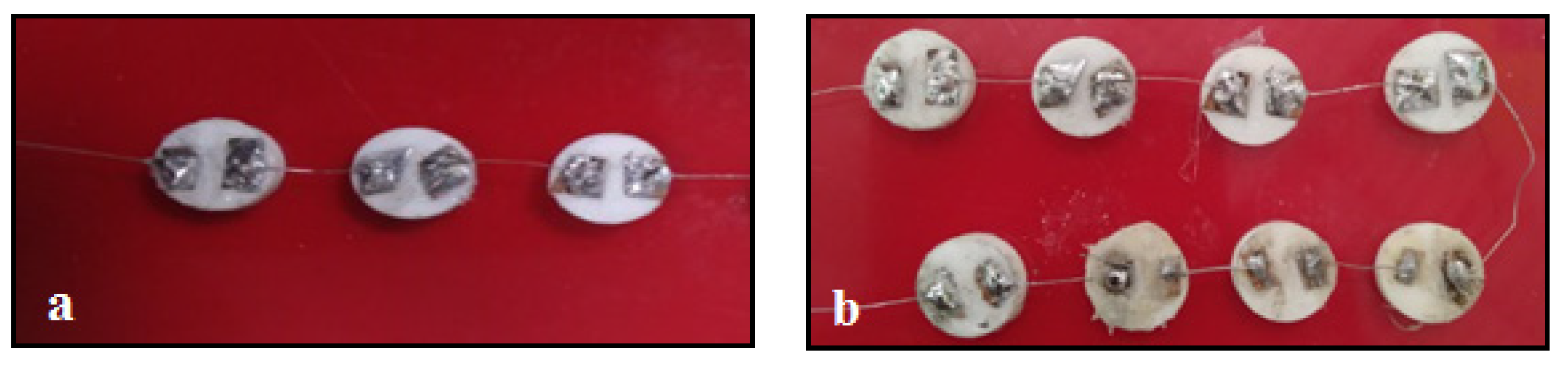

2.4. Real-Time Testing of the Sensor

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structural Properties of SnO2 by XRD Analysis

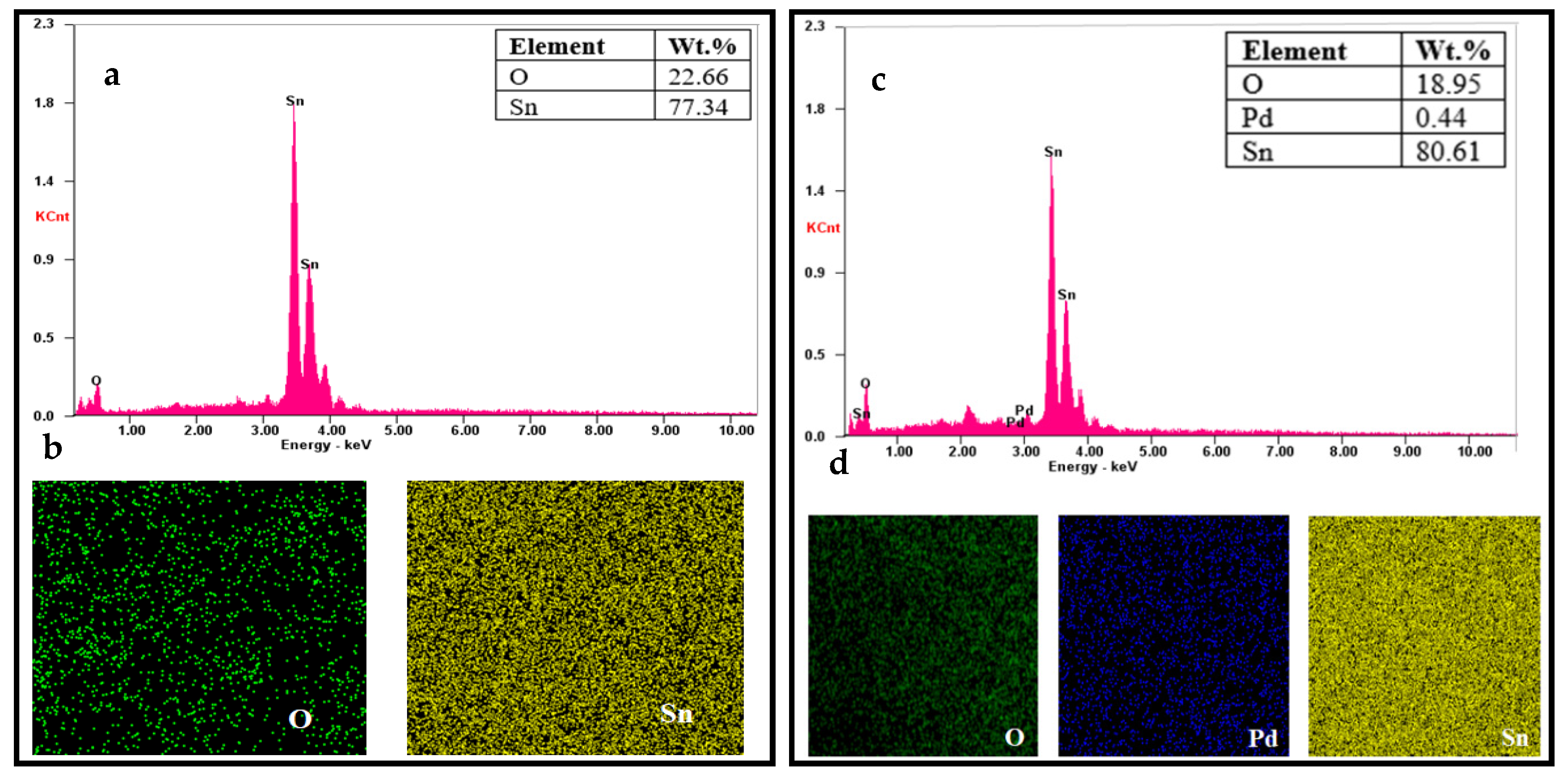

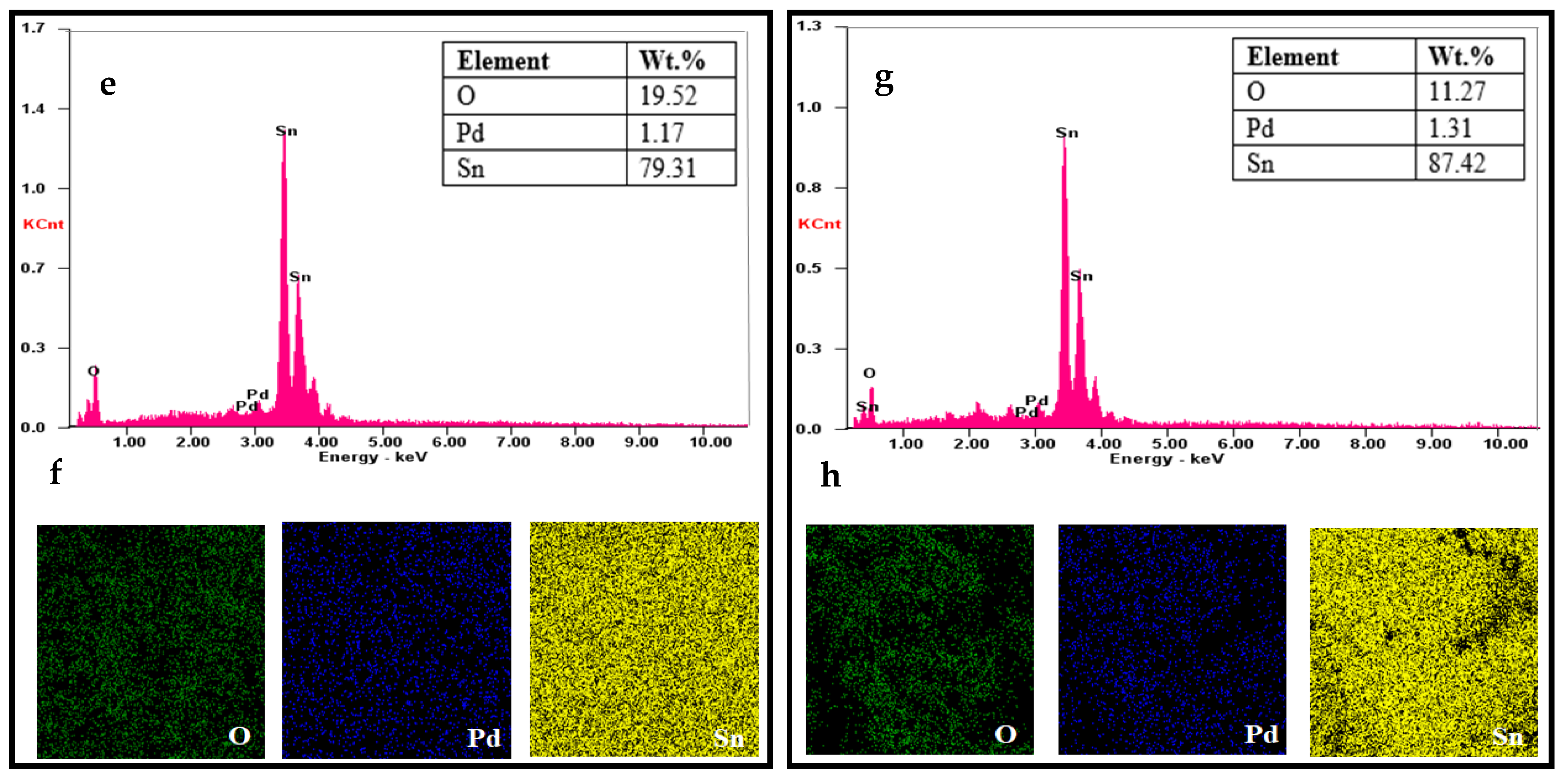

3.2. Morphological Properties of SnO2 by FESEM Analysis

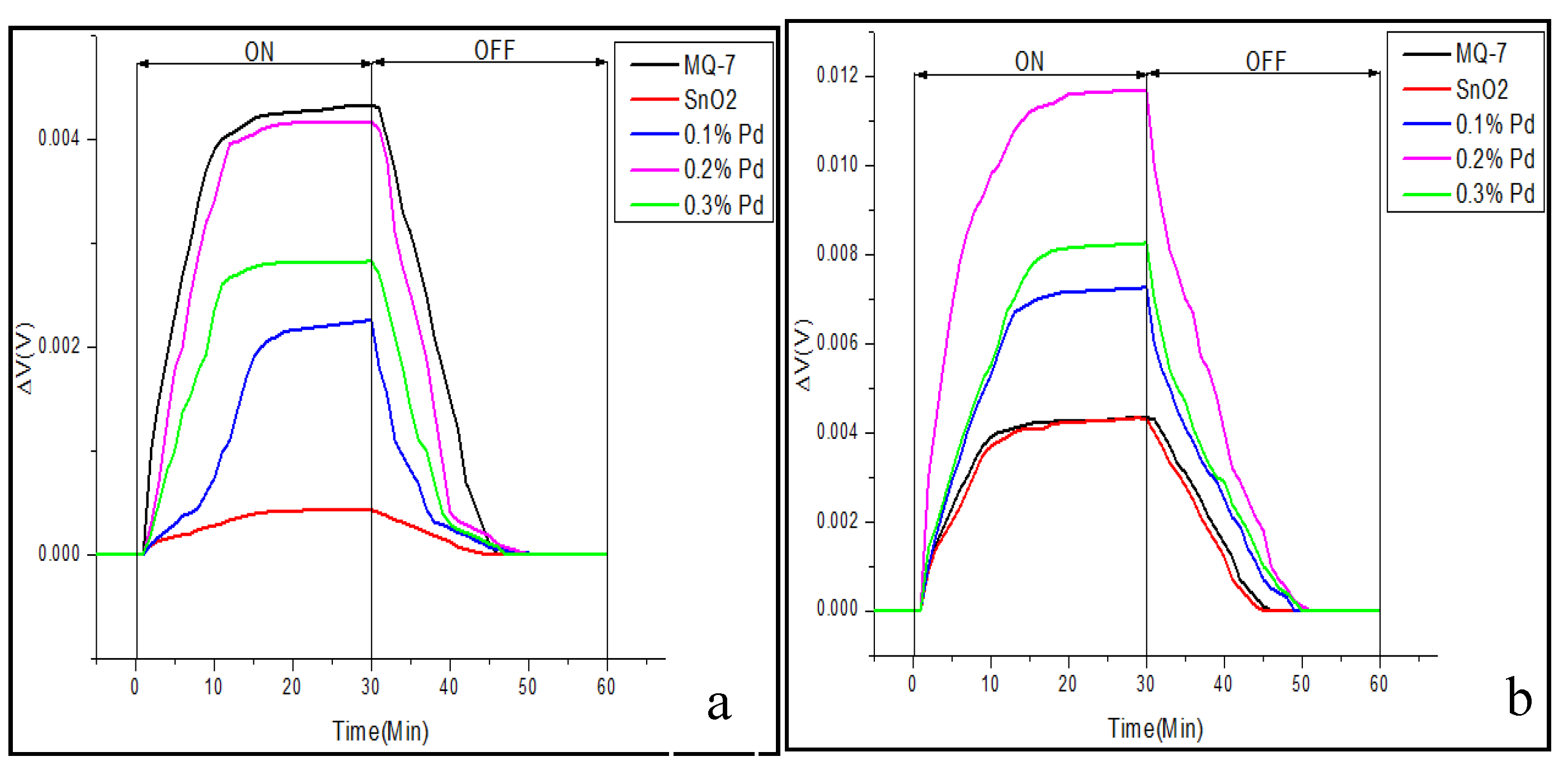

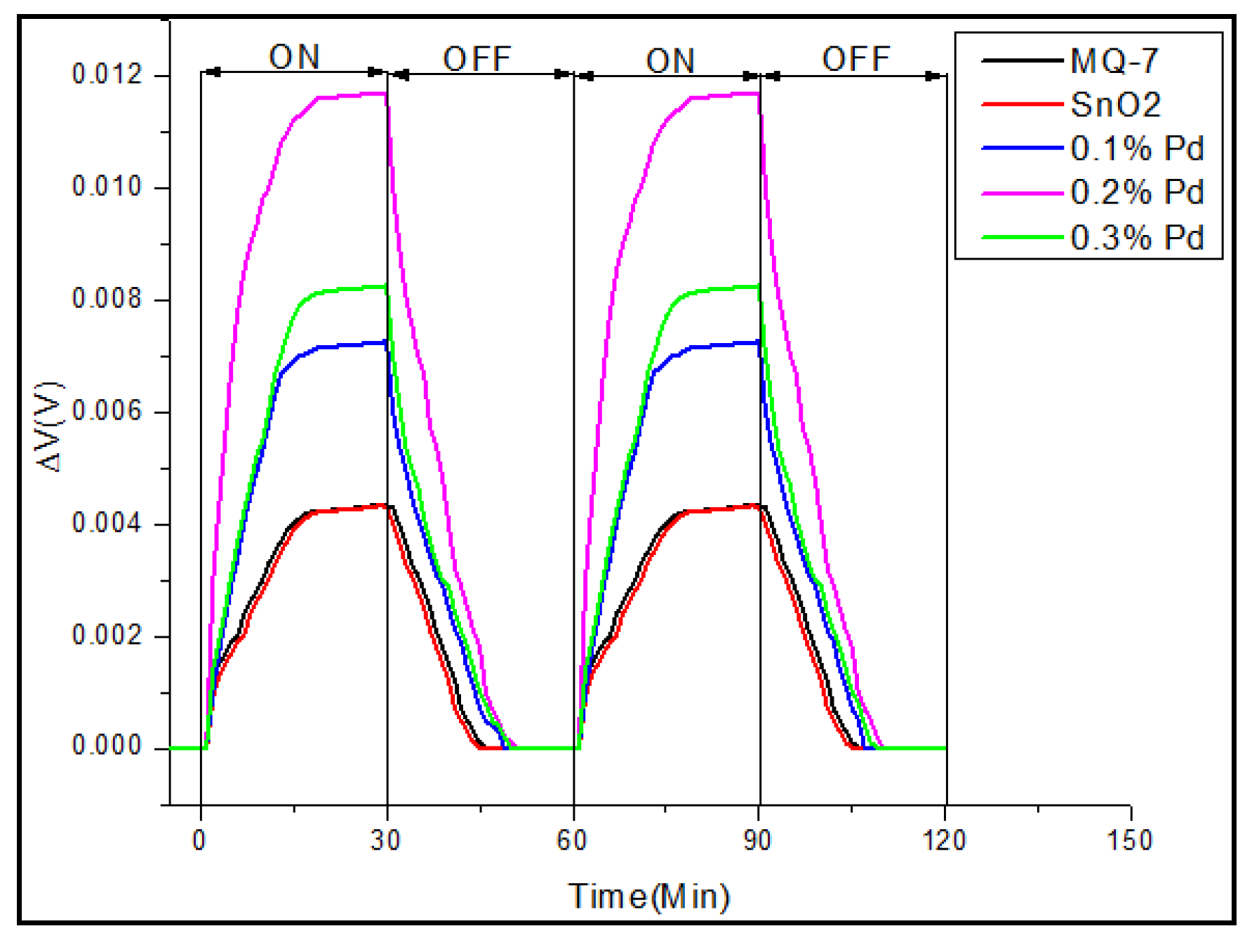

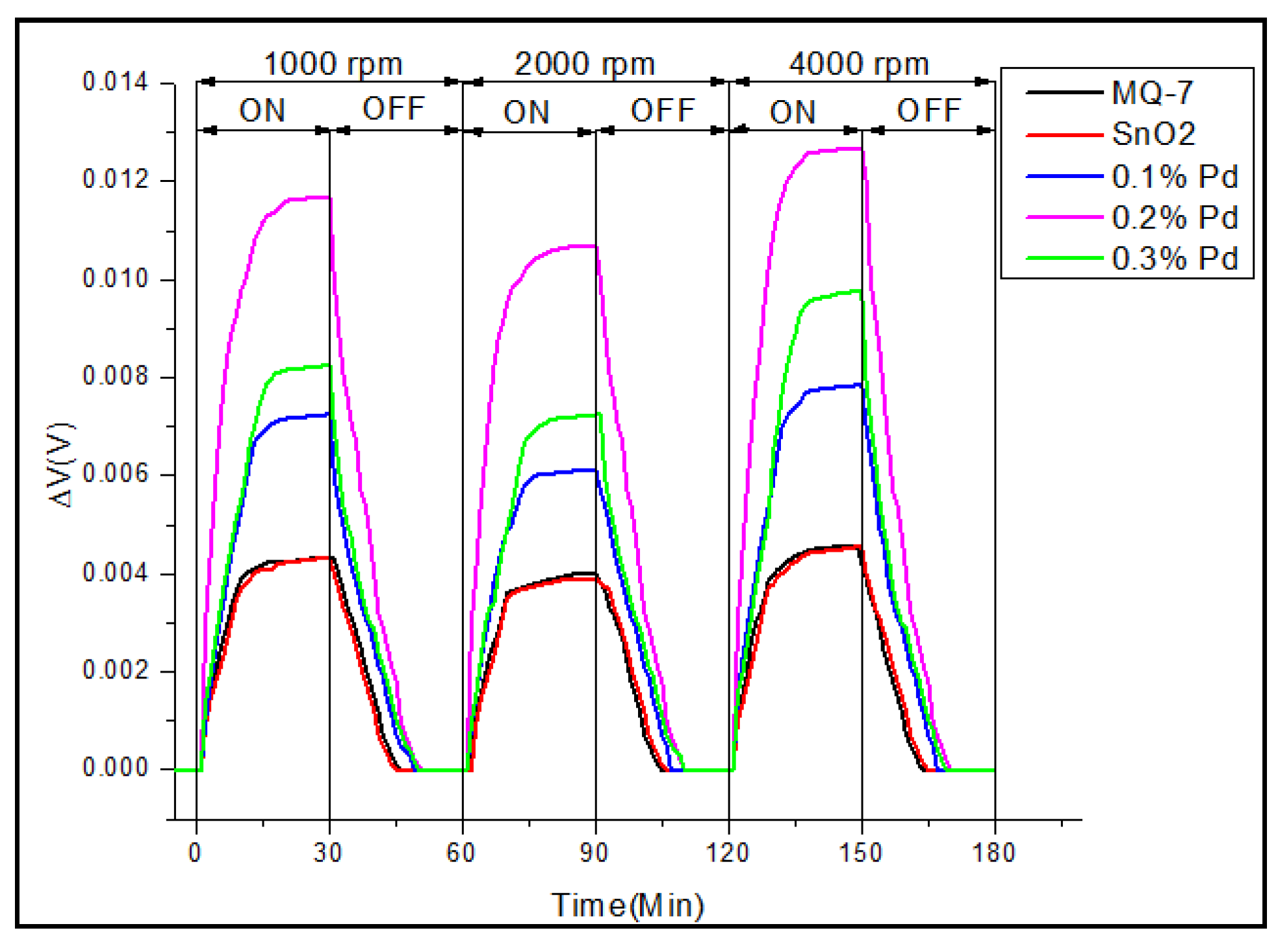

3.3. Real-Time Testing of the Sensor

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tong, S. Air pollution and disease burden. Lancet Planet. Health Comment 2019, 3, 49–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliarto, B.; Gumilar, G.; Septiani, N.L.W. SnO2 nanostructure as pollutant gas sensors: Synthesis, sensing performances, and mechanism. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godish, T. Atmospheric pollution and pollutants. In Air Quality, 4th ed.; Lewis Publishers: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004; pp. 26–75. [Google Scholar]

- Omaye, S.T. Metabolic modulation of carbon monoxide toxicity. Toxicology 2002, 180, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.M.; Sampath, S.; Jeena, V.S.; Anjali, R. Carbon monoxide pollution levels at environmentally different sites. J. Indian Geophys. Union 2008, 12, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Rozante, J.R.; Rozante, V.; Alvim, D.S.; Manzi, A.O.; Chiquetto, J.B.; D’Amelio, M.T.S.; Moreira, D.S. Variations of carbon monoxide concentrations in the megacity of São Paulo from 2000 to 2015 in different time scales. Atmosphere 2017, 8, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myronuk, D.J. Augmented ingestion of carbon monoxide and sulfur oxides by occupants of vehicles while idling in drive-up facility lines. Water Air Soil Pollut. 1977, 7, 203–213. [Google Scholar]

- Penney, D.G. A survey study of public perceptions about carbon monoxide. In Carbon Monoxide Poisoning; Penney, D.G., Ed.; Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008; pp. 325–340. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.X.; Yin, L.W.; Zhang, L.Y.; Xiang, D.; Gao, R. Metal oxide gas sensors: Sensitivity and influencing factors. Sensors 2010, 10, 2088–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Wu, W.; Gao, J.; Lu, J.; Fan, C. Nanomaterials-based sensors for applications in environmental monitoring. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 18101–18110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, I.Y.; Tajuddin, A.A.; Noor, H.A.; Lim, C.M.; Mahadi, A.H.; Kumara, N.T.R.N. Enhanced carbon monoxide-sensing properties of chromium-doped ZnO nanostructures. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, W.; Wang, H.; Li, Z. Nanomaterials for sensing applications. J. Nanotechnol. 2016, 2016, 2083948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanan, S.M.; El-Kadri, O.M.; Abu-Yousef, I.A.; Kanan, M.C. Semiconducting metal oxide based sensors for selective gas pollutant detection. Sensors 2009, 9, 8158–8196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanazawa, E.; Sakai, G.; Shimanoe, K.; Kanmura, Y.; Teraoka, Y.; Miura, N.; Yamazoe, N. Metal oxide semiconductor N2O sensor for medical use. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2001, 77, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, S.; Agarwal, A.; Agarwal, R. A comparative study of gas sensing properties of tungsten oxide, tin oxide and tin-doped tungsten oxide thin films for acetone gas detection. J. Electron. Mater. 2019, 48, 1617–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.E.; Rahman, A.Z.M.S. Metal-oxide-based gas sensors. In Reference Module in Materials Science and Materials Engineering; Elsevier Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.P.; Wang, J.; Li, Q.Q.; Liu, H.G.; Li, Y. A review of recent developments in tin dioxide composites for gas sensing application. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2016, 44, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govardhan, K.; Nirmala, A. Grace metal/metal oxide doped semiconductor based metal oxide gas sensors—A review. Sens. Lett. 2016, 14, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramgir, N.S.; Hwang, Y.K.; Jhung, S.H.; Kim, H.K.; Hwang, J.S.; Mulla, I.S.; Chang, J.S. CO sensor derived from mesostructured Au-doped SnO2 thin film. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2006, 252, 4298–4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Chen, W.; Xu, L.; Kumar, R.; Gui, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Tang, C.; Zhu, S. Highly sensitive carbon monoxide CO) gas sensors based on Ni and Zn doped SnO2 nanomaterials. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 4392–4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basyooni, M.A.; Eker, Y.R.; Yilmaz, M. Structural, optical, electrical and room temperature gas sensing characterizations of spin coated multilayer cobalt-doped tin oxide thin films. Superlattices Microstruct. 2020, 140, 106465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombak, A.; Ocak, Y.S.; Bayansal, F. Cu/SnO2 gas sensor fabricated by ultrasonic spray pyrolysis for effective detection of carbon monoxide. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 493, 1075–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navazani, S.; Shokuhfar, A.; Hassanisadi, M.; Di Carlo, A.; Nia, N.Y.; Agresti, A. A PdPt decorated SnO2-rGO nanohybrid for high-performance resistive sensing of methane. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2019, 95, 438–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Li, Y.; Ran, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, R.; Su, L.; Kong, Y.; Ma, D.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y. Construction of novel Pd–SnO2 composite nanoporous structure as a high-response sensor for methane gas. J. Alloy. Compd. 2020, 826, 154063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmakov, A.; Klenov, D.O.; Lilach, Y.; Stemmer, S.; Moskovits, M. Enhanced gas sensing by individual SnO2 nanowires and nanobelts functionalized with Pd catalyst particles. Nano Lett. 2005, 5, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Li, L.; Jiang, W.; Liu, C.; Ding, W.; Chai, W. Crystallinity and morphology-controlled synthesis of SnO2 nanoparticles for higher gas sensitivity. Powder Technol. 2013, 245, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firooz, A.A.; Mahjoub, A.R.; Khodadadi, A.A. Effects of flower-like, sheet-like and granular SnO2 nanostructures prepared by solid-state reactions on CO sensing. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2009, 115, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel-Garcia, I.; Berenguer-Murcia, A.; Cazorla-Amoros, D. Preferential oxidation of CO catalyzed by supported polymer-protected palladium-based nanoparticles. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2010, 98, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasthurirengan, S.; Behera, U.; Nadig, D.S.; Weisend, J.G. Palladium doped tin oxide based hydrogen gas sensors for safety applications. AIP Conf. Proc. 2010, 1218, 1239–1246. [Google Scholar]

- Jarzebski, Z.M.; Marton, J.P. Physical properties of SnO2 materials: I. Preparation and defect structure. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1976, 123, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debataraja, A.; Septiani, N.L.W.; Yuliarto, B.; Nugraha, N.; Sunendar, B.; Abdullah, H. High performance of a carbon monoxide sensor based on a Pd-doped graphene-tin oxide nanostructure composite. Ionics 2019, 25, 4459–4468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blessi, S.; Sonia, M.; Vijayalakshmi, S.; Pauline, S. Preparation and characterization of SnO2 nanoparticles by hydrothermal method. Int. J. ChemTech Res. 2014, 6, 2153–2155. [Google Scholar]

- Naje, A.N.; Norry, A.S.; Suhail, A.M. Preparation and characterization of SnO2 nanoparticles. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2013, 2, 7068–7072. [Google Scholar]

- Inderan, V.; Arafat, M.M.; Haseeb, A.S.M.A.; Sudesh, K.; Lee, H.L. A comparative study of structural and ethanol gas sensing properties of pure, nickel and palladium doped SnO2 nanorods synthesised by the hydrothermal method. J. Phys. Sci. 2019, 30, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niranjan, R.S.; Hwang, Y.K.; Kim, D.K.; Jhung, S.H.; Chang, J.S.; Mulla, I.S. Nanostructured tin oxide: Synthesis and gas-sensing properties. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2005, 92, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranya, M.; Santhosh, C.; Augustine, S.P.; Grace, A.N. Synthesis and characterization of CuS nanomaterials using hydrothermal route. J. Exp. Nanosci. 2014, 9, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskandari, P.; Farhadian, M.; Nazar, A.R.S.; Jeon, B.-H. Adsorption and photodegradation efficiency of TiO2/Fe2O3/PAC and TiO2/Fe2O3/Zeolite nanophotocatalysts for the removal of cyanide. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 2099–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, C.; Schrapler, L.; Herklotz, G. Doped and low-alloyed gold bonding wires. Gold Bull. 2000, 33, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.M.; Chon, B.S.; Jeon, S.H.; Rai, P.; Yu, Y.T.; Dutta, P.K. Synthesis of Au@SnO2 core–shell nanoparticles with controllable shell thickness and their CO sensing properties. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2015, 166, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Qin, H.; Hu, J. CO sensing properties and mechanism of Pd doped SnO2 thick-films. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 428, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, P.G.; Izu, N.; Shirahata, N.; Masuda, Y. Improvement of sensing properties for SnO2 gas sensor by tuning of exposed crystal face. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 296, 126655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhou, Q.; Gao, T.; Su, X.; Wan, F. Pd-doped SnO2-based sensor detecting characteristic fault hydrocarbon gases in transformer oil. J. Nanomater. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Liang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, M.; Li, P.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhuiykov, S. Highly sensitive NO2 detection on ppb level by devices based on Pd-loaded In2O3 hierarchical microstructures. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 252, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso, A.J.; Tessarolo, E.; Guidolin, M.; Della Gaspera, E.; Martucci, A.; Angiola, M.; Pelizzo, M.G. Room-temperature optical detection of hydrogen gas using palladium nano-islands. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2018, 43, 5783–5792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, G.E.; Kajale, D.D.; Gaikwad, V.B.; Jain, G.H. Preparation and characterization of SnO2 nanoparticles by hydrothermal route. Int. Nano Lett. 2012, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuasa, M.; Masaki, T.; Kida, T.; Shimanoe, K.; Yamazoe, N. Nano-sized PdO loaded SnO2 nanoparticles by reverse micelle method for highly sensitive CO gas sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2009, 136, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Sharif, S.; Anjum, S.; Imran, M.; Ikram, M.; Naz, M.; Ali, S. Preparation of Co and Ni doped ZnO nanoparticles served as encouraging nano-catalytic application. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 1250d5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineau, N.J.; Keller, S.D.; Güntner, A.T.; Pratsinis, S.E. Palladium embedded in SnO2 enhances the sensitivity of flame-made chemoresistive gas sensors. Microchim. Acta 2020, 187, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koziej, D.; Hubner, M.; Barsan, N.; Weimar, U.; Sikora, M.; Grunwaldt, J.-D. Operando X-ray absorption spectroscopy studies on Pd-SnO2 based sensors. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2009, 11, 8620–8625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandy, T.; Coutu, R.A., Jr.; Ababei, C. Carbon monoxide sensing technologies for next-generation cyber-physical systems. Sensors 2018, 18, 3443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menini, P.; Parret, F.; Guerrero, K.; Soulantica, K.; Erades, L.; Maisonnat, A.; Chaudret, B. CO response of a nanostructured SnO2 gas sensor doped with palladium and platinum. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2004, 103, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilicarslana, A.; Qatub, M. Exhaust gas analysis of an eight cylinder gasoline engine based on engine speed. Energy Procedia 2017, 110, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisser, M.; Badcock, R.A.; Teal, P.D.; Hunze, A. Optimizing the sensitivity of palladium based hydrogen sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 259, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meenakshi, C.; Mishra, V.N.; Dwivedi, R. Platinum and palladium doped tin oxide thick film sensors for sensing methane and hydrogen. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Communication and Electronics System Design, SPIE 8760, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India, 28 January 2013; p. 87601X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Bian, C.; Kuang, J.; Wang, J.; Tong, J.; Xia, S. A palladium-tin modified microband electrode array for nitrate determination. Sensors 2015, 15, 23249–23261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, J.; Park, J.A.; Lee, S.J.; Zyung, T.; Kim, I.D. Pd-doped TiO2 nanofiber networks for gas sensor applications. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2010, 149, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorenko, G.; Oleksenko, L.; Maksymovych, N.; Skolyar, G.; Ripko, O. Semiconductor gas sensors based on Pd/SnO2 nanomaterials for methane detection in air. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.-T.; Guo, X.-M. Selectivity and sensitivity of Pd-loaded and Fe-doped SnO2 sensor for CO detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 200, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasaltin, C. Sensor properties of Pd doped SnO2 nanofiber enshrouded with functionalized MWCNT. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.03031. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Fu, H.; Jin, O.; Jin, H.; Haick, H.; Wang, S.; Yu, K.; Dengh, S.; Wang, Y. Directly transforming SnS2 nanosheets to hierarchical SnO2 nanotubes: Towards sensitive and selective sensing of acetone at relatively low operating temperatures. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 292, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayago, I.; Aleixandre, M.; Santos, J.P. Development of tin oxide-based nanosensors for electronic nose environmental applications. Biosensors 2019, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Qiao, Q.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Jian, J. Gas sensing behavior of palladium oxide for carbon monoxide at low working temperature. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015, 212, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Yuan, T.; Yuan, H.; Zheng, X.; Ijaz, H.; Hui, J.; Fan, D.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, S. PdO/SnO2 heterostructure for low-temperature detection of CO with fast response and recovery. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 22875–22882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Absalan, S.; Nasresfahani, S.; Sheikhi, M.H. High-performance carbon monoxide gas sensor based on palladium/tin oxide/porous graphitic carbon nitride nanocomposite. J. Alloy. Compd. 2019, 795, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Liu, X.; Yu, W. Research progress of gas sensor based on graphene and its derivatives: A review. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Kundu, V.S.; Maan, A.S. Structural, morphological and gas sensing study of palladium doped tin oxide nanoparticles synthesized via hydrothermal technique. J. Mol. Struct. 2015, 1100, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sam Jebakumar, J.; Juliet, A.V. Palladium-Doped Tin Oxide Nanosensor for the Detection of the Air Pollutant Carbon Monoxide Gas. Sensors 2020, 20, 5889. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20205889

Sam Jebakumar J, Juliet AV. Palladium-Doped Tin Oxide Nanosensor for the Detection of the Air Pollutant Carbon Monoxide Gas. Sensors. 2020; 20(20):5889. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20205889

Chicago/Turabian StyleSam Jebakumar, Jeyapaul, and Asokan Vimala Juliet. 2020. "Palladium-Doped Tin Oxide Nanosensor for the Detection of the Air Pollutant Carbon Monoxide Gas" Sensors 20, no. 20: 5889. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20205889

APA StyleSam Jebakumar, J., & Juliet, A. V. (2020). Palladium-Doped Tin Oxide Nanosensor for the Detection of the Air Pollutant Carbon Monoxide Gas. Sensors, 20(20), 5889. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20205889