Cross Lingual Sentiment Analysis: A Clustering-Based Bee Colony Instance Selection and Target-Based Feature Weighting Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Studies

2.1. Challenges of CROSS-LINGUAL Sentiment Analysis

2.2. Main Techniques for CROSS-LINGUAL Sentiment Analysis (CLSA)

2.3. Main Techniques for Instance Selection and Feature Weighting

3. The Proposed Method

3.1. Clustering Based on BEE-COLONY Training Instance Selection

3.2. Clustering Target Language Data

- (i)

- Inferring a target data similarity matrix: Given an unlabeled target data set consisting of the feature vectors of m unlabeled reviews, , The similarity matrix element is computed between each pair of the unlabeled reviews () from the target language dataset using cosine similarity measure as in Equation (1):The constructed similarity matrix is built through computing pair-wise similarity between the target set instances:

- (ii)

- Estimating reviews density: A random number is selected where . The algorithm then calculates the density of each unlabeled review of the data as:where is the cosine similarity between two feature vectors of review and . is the density of review, is the set of all reviews whose cosine similarity such that the review is greater than r. After computing the density function for all reviews, a review which has the highest density (i.e., ) is then chosen as the seed of the first , i.e., review which has most similar reviews, and all reviews in density set are removed from the data set.

- (iii)

- The centroid of each cluster: Given the selected review and all reviews in its density set, the centroid of a formed cluster is computed as average of the feature vectors of all cluster members (i.e., density set members), as shown in the equation below:where is the centroid of the formed cluster, is the number of reviews in the cluster and is the feature vector of review

- (iv)

- Selection Q optimal target clusters: Repeat step (iii) and step (iv) to continue selecting the subsequent clusters as long as the algorithm continues to find documents in the data set.

3.3. Improved Artificial BEE-COLONY Training Selection

- (1)

- For each review from the solution ( selected sample from the source), the algorithm finds the maximum similarity of review and each centroid of the target clusters as follows:where can be defined as the maximum similarity of a review and the target data.

- (2)

- Then, the fitness of the solution is defined as average of total maximum similarity of all of its reviews and calculated as follows:

| Algorithm 1. ABC algorithm Pseudo code |

| Input: Translated Training Data, Q optimal target clusters, S centroids of target clusters Output: Optimal Training Data |

| For each Cluster Ci in Q target clusters |

| (1) Generate the initial population { (2) Assess the fitness of the population using Equation (9) (3) Let cycle to be 1 |

| (4) Repeat |

| (5) FOR each solution (employed bee) |

| Begin Find new solution from with Equation (11) Determine the fitness value using Equation (9) Employ greedy process EndFor |

| (6) Find probability values for the solutions utilizing Equation (10) |

| (7) FOR every onlooker bee |

| Begin Choose solution based on Generate new solution from utilizing Equation (11) Determine the fitness value using Equation (9) Employ greedy selection process EndFor |

| (8) If abandoned solution for the scout is determined, Begin |

| swap it with a new solution |

| randomly generated using Equation (12) EndIF |

| (9) Remember the best solution up to this point |

| (10) increase cycle by 1 |

| (11) Until cycle equals to MCN |

3.4. Target-Based Feature Selection Methods

| Algorithm 2. Algorithm for integrating prior supervised information with semi-supervised training. |

| Input:UT Test Unlabeled data from the target language, LS: Selected labeled training sample from Source language. Output: Unconfident Group UG, Prior Label matrix PL, confident group CG Begin |

|

(1)

Train classifier C1 on LS. (2) Train classifier C2 on LS. (3) Train classifier C3 on LS. // C1, C2 and C3 used to predict class label and calculate // the prediction confidence of each example in U (4) For Each (Example ui in UT) Begin // calculate average confidence values Begin Else (5) End |

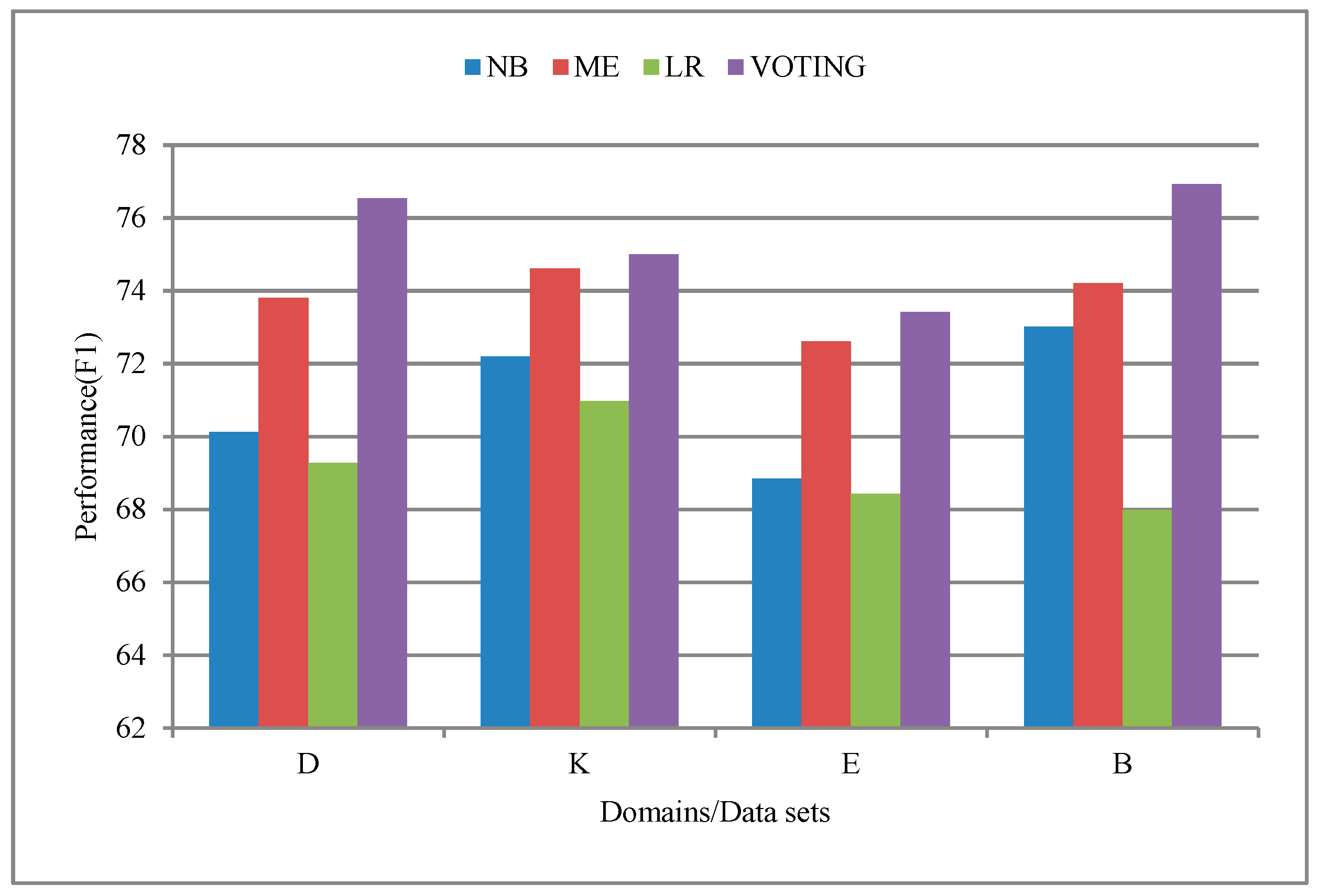

3.5. Ensemble Supervised Learning

- (1)

- Using different types of base classifiers.

- (2)

- Selecting samples that contain instances generated randomly, and

- (3)

- Selecting samples that are distributed in a representative and informative way. The final prediction output of the ensemble model is obtained by averaging the confidence values for each label.

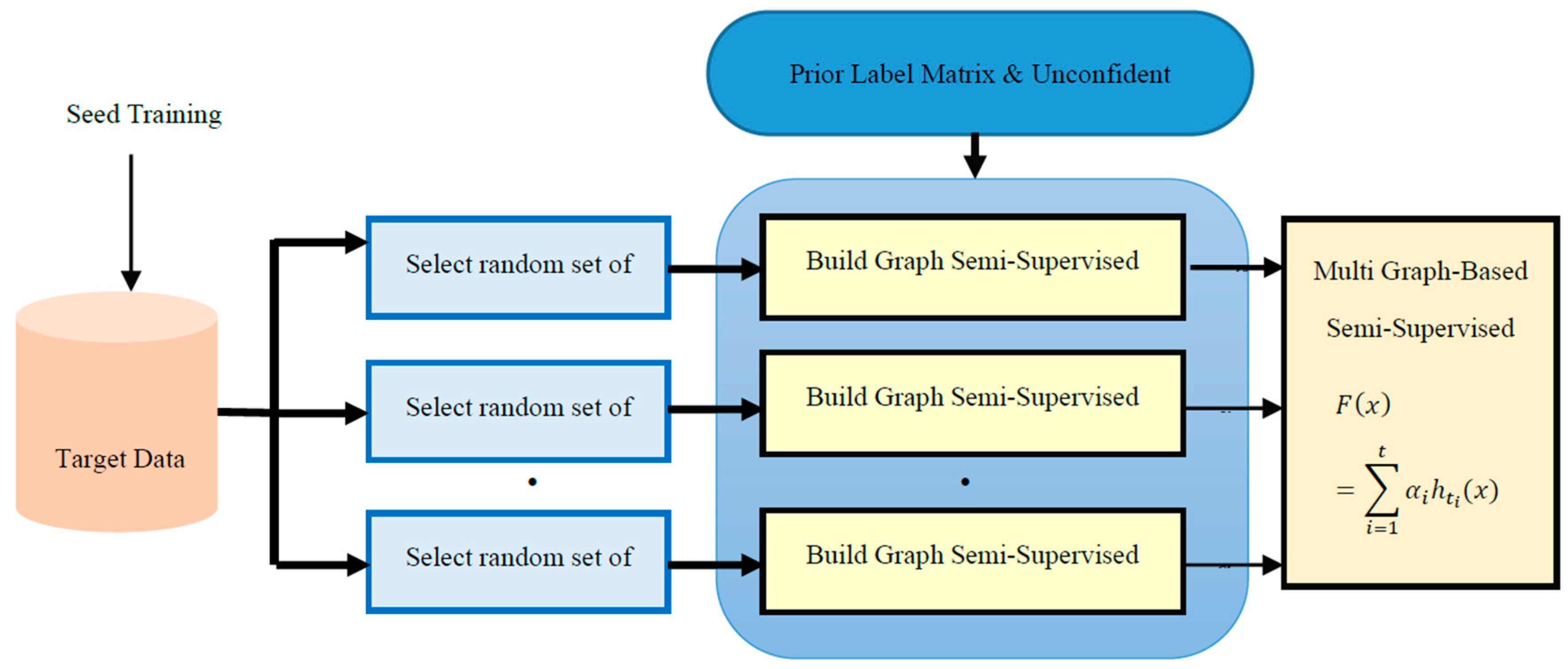

3.6. Integrating Prior Supervised Information with Semi-Supervised

3.7. SEMI-SUPERVISED Learning

- Step (1)

- Each review is represented as a feature vector.

- Step (2)

- Initialize the label matrix for the labeled data set. and is described above.

- Step (3)

- Randomly select features from all features

- Step (4)

- Graph construction:

- (a)

- Each a labeled or unlabelled review, a node is assigned. Allow to be a set of vertices.

- (b)

- K-NN node calculation: To construct the graphs, the nearest neighbor method is employed. Two nearest k neighbors set a review of and is determined where is a set of nearest unlabeled neighbors, and is a set of nearest labeled neighbors of . A review is assigned to one of the k nearest neighbors set of review if their edge weight between their feature vectors is greater than . The weight of an edge is defined with the Gaussian kernel:where is the feature vector of review xi, Weight matrix is constructed.

- Step (1)

- Run semi-supervised inference on this graph utilizing label propagation:Finally, NormalizeRepeat the above steps n times from step 3 to build n trained semi-supervised modelsEach trained with different feature set;

- Step (2)

- The n Semi-Supervised classifier vote to determine the final labels for the unlabeled data .

4. Experimental Design

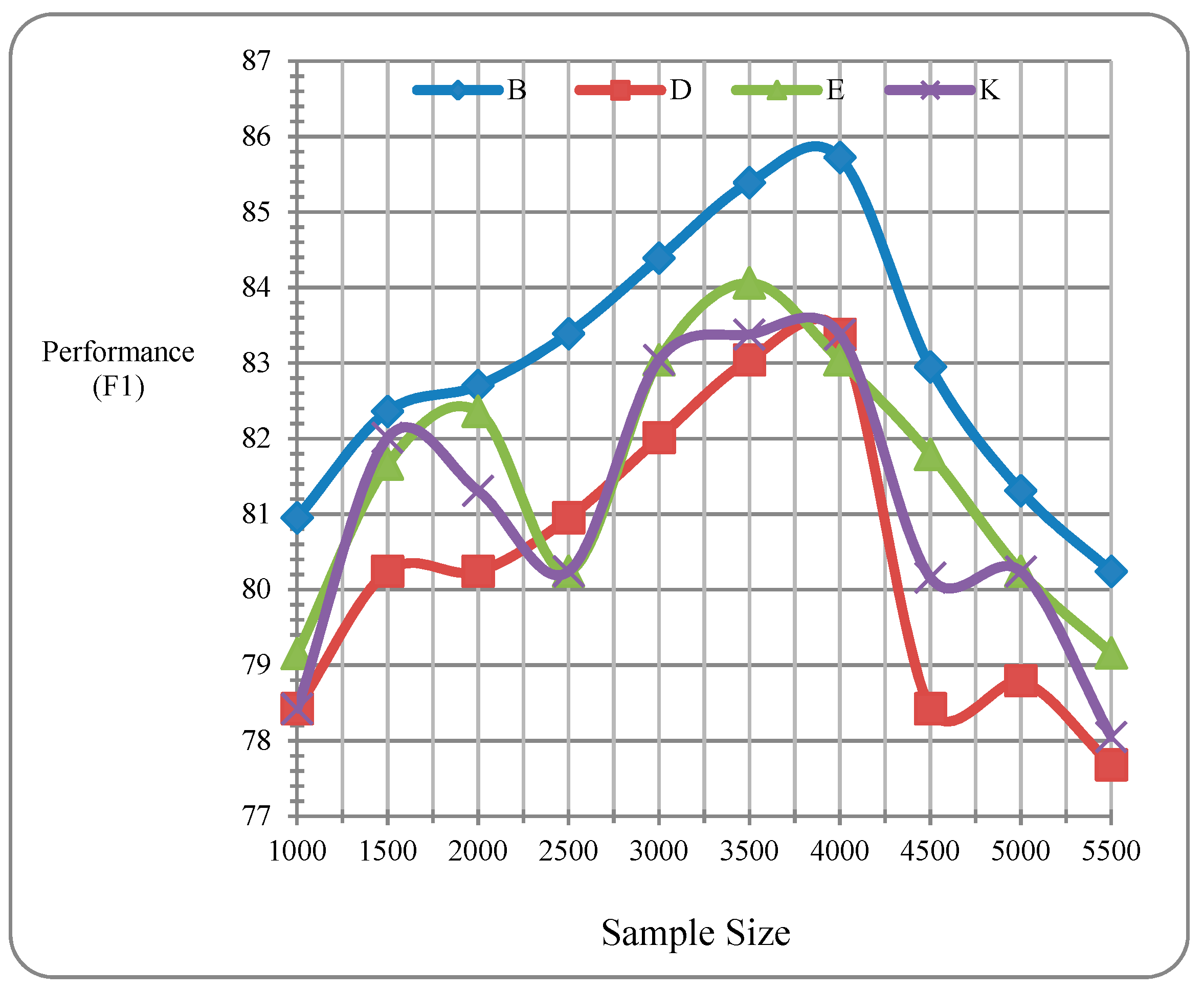

5. Result and Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hajmohammadi, M.S.; Ibrahim, R.; Selamat, A.; Fujita, H. Combination of active learning and self-training for cross-lingual sentiment classification with density analysis of unlabelled samples. Inf. Sci. 2015, 317, 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Balahur, A.; Turchi, M. Comparative experiments using supervised learning and machine translation for multilingual sentiment analysis. Comput. Speech Lang. 2014, 28, 56–75. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shabi, A.; Adel, A.; Omar, N.; Al-Moslmi, T. Cross-lingual sentiment classification from english to arabic using machine translation. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2017, 8, 434–440. [Google Scholar]

- Rasooli, M.S.; Farra, N.; Radeva, A.; Yu, T.; McKeown, K. Cross-lingual sentiment transfer with limited resources. Mach. Transl. 2018, 32, 143–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, R.; Zong, C.; Hu, X.; Cambria, E. Feature ensemble plus sample selection: Domain adaptation for sentiment classification. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2013, 28, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Mei, C.; Chen, D.; Yang, Y. A fuzzy rough set-based feature selection method using representative instances. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2018, 151, 216–229. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Wei, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liao, T. Sentiment analysis of Chinese micro-blog text based on extended sentiment dictionary. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2018, 81, 395–403. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Lu, K.; Su, S.; Wang, S. Chinese micro-blog sentiment analysis based on multiple sentiment dictionaries and semantic rule sets. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 183924–183939. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Wang, S.; Li, D. Cross-lingual sentiment classification: Similarity discovery plus training data adjustment. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2016, 107, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.-B.; Jin, Y.; Li, N.; Su, X.; Cardiff, B.; Bhanu, B. Words alignment based on association rules for cross-domain sentiment classification. Front. Inf. Technol. Electron. Eng. 2018, 19, 260–272. [Google Scholar]

- Salameh, M.; Mohammad, S.; Kiritchenko, S. Sentiment after translation: A case-study on arabic social media posts. In Proceedings of the 2015 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Denver, CO, USA, 31 May–5 June 2015; pp. 767–777. [Google Scholar]

- Demirtas, E.; Pechenizkiy, M. Cross-lingual polarity detection with machine translation. In Proceedings of the Second International Workshop on Issues of Sentiment Discovery and Opinion Mining, Chicago, IL, USA, 11 August 2013; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, K.; Moreira, V.P.; dos Santos, A.G. Multilingual emotion classification using supervised learning: Comparative experiments. Inf. Process. Manag. 2017, 53, 684–704. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wei, F.; Liu, X.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, M. Topic sentiment analysis in twitter: A graph-based hashtag sentiment classification approach. In Proceedings of the 20th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Scotland, UK, 24–28 October 2011; pp. 1031–1040. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar, M.S.; Sawant, P.; Sen, S.; Ekbal, A.; Bhattacharyya, P. Solving data sparsity for aspect based sentiment analysis using cross-linguality and multi-linguality. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long Papers), New Orleans, LA, USA, 1–6 June 2018; pp. 572–582. [Google Scholar]

- Balahur, A.; Turchi, M. Multilingual sentiment analysis using machine translation? In Proceedings of the 3rd Workshop in Computational Approaches to Subjectivity and Sentiment Analysis, Jeju, Korea, 12–13 July 2012; pp. 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mihalcea, R.; Banea, C.; Wiebe, J. Learning multilingual subjective language via cross-lingual projections. In Proceedings of the 45th Annual Meeting of the Association of Computational Linguistics, Prague, Czech Republic, 23–30 June 2007; pp. 976–983. [Google Scholar]

- Prettenhofer, P.; Stein, B. Cross-lingual adaptation using structural correspondence learning. Acm Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. (TIST) 2011, 3, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Blitzer, J.; Dredze, M.; Pereira, F. Biographies, bollywood, boom-boxes and blenders: Domain adaptation for sentiment classification. In Proceedings of the 45th Annual Meeting of the Association of Computational Linguistics, Prague, Czech Republic, 23–30 June 2007; pp. 440–447. [Google Scholar]

- Hajmohammadi, M.S.; Ibrahim, R.; Selamat, A. Bi-view semi-supervised active learning for cross-lingual sentiment classification. Inf. Process. Manag. 2014, 50, 718–732. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Sun, Y.; Athiwaratkun, B.; Cardie, C.; Weinberger, K. Adversarial deep averaging networks for cross-lingual sentiment classification. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2018, 6, 557–570. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Zhai, S.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, B. Structural correspondence learning for cross-lingual sentiment classification with one-to-many mappings. In Proceedings of the Thirty-First AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, San Francisco, CA, USA, 4–9 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, M.; Guo, Y. Semi-Supervised Matrix Completion for Cross-Lingual Text Classification. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Eighth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Québec City, QC, Canada, 27–31 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Abdalla, M.; Hirst, G. Cross-lingual sentiment analysis without (good) translation. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.01626. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Li, W.; Lei, Y.; Liu, X.; Luo, C.; He, Y. Cross-Lingual Sentiment Relation Capturing for Cross-Lingual Sentiment Analysis. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Information Retrieval, Aberdeen, UK, 8–13 April 2017; pp. 54–67. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, S.; Batra, S. Cross lingual sentiment analysis using modified BRAE. In Proceedings of the 2015 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Lisbon, Portugal, 17–21 September 2015; pp. 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Wan, X.; Xiao, J. Attention-based LSTM network for cross-lingual sentiment classification. In Proceedings of the 2016 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing, Austin, TX, USA, 1–4 November 2016; pp. 247–256. [Google Scholar]

- Abdalla, M.M.S.A. Lowering the Cost of Improved Cross-Lingual Sentiment Analysis. 2018. Available online: http://ftp.cs.utoronto.ca/cs/ftp/pub/gh/Abdalla-MSc-thesis-2018.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2020).

- Wan, X. Co-training for cross-lingual sentiment classification. In Proceedings of the Joint Conference of the 47th Annual Meeting of the ACL and the 4th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing of the AFNLP: Volume 1-volume 1, Suntec, Singapore, 7–12 August 2009; pp. 235–243. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, X. Bilingual co-training for sentiment classification of Chinese product reviews. Comput. Linguist. 2011, 37, 587–616. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, J.; Klinger, R.; Walde, S.S.i. Bilingual sentiment embeddings: Joint projection of sentiment across languages. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1805.09016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wen, J.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Z. Semi-supervised learning combining co-training with active learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2014, 41, 2372–2378. [Google Scholar]

- Kouw, W.M.; Loog, M. A review of domain adaptation without target labels. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahat, A.K.; Ghodsi, A.; Kamel, M.S. A Fast Greedy Algorithm for Generalized Column Subset Selection. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.6820. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, R.; Hu, X.; Lu, J.; Yang, J.; Zong, C. Instance selection and instance weighting for cross-domain sentiment classification via PU learning. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Third International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Beijing, China, 3–9 August 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, R.; Pan, Z.; Xu, F. Instance weighting for domain adaptation via trading off sample selection bias and variance. In Proceedings of the 27th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Stockholm, Sweden, 13–19 July 2018; pp. 4489–4495. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Fan, W.; Luo, Y. A method on selecting reliable samples based on fuzziness in positive and unlabeled learning. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1903.11064. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F.; Yu, J.; Xia, R. Instance-based domain adaptation via multiclustering logistic approximation. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2018, 33, 78–88. [Google Scholar]

| Dataset/Features | Books | DVDS | Electronics | Kitchen |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of reviews | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 |

| Positive | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 |

| Negative | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 |

| No of features | 188,050 | 179,879 | 104,027 | 89,478 |

| Average length/review | 239 | 234 | 153 | 131 |

| Model | Target Data Set | Precision | Recall | F-Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NB | D | 70.59 | 69.68 | 70.13 |

| K | 72.44 | 71.97 | 72.2 | |

| E | 68.18 | 69.54 | 68.85 | |

| B | 74.19 | 71.88 | 73.02 | |

| ME | D | 74.05 | 73.58 | 73.81 |

| K | 74.84 | 74.38 | 74.61 | |

| E | 73.08 | 72.15 | 72.61 | |

| B | 73.75 | 74.68 | 74.21 | |

| LR | D | 67.95 | 70.67 | 69.28 |

| K | 70.06 | 71.9 | 70.97 | |

| E | 69.33 | 67.53 | 68.42 | |

| B | 67.76 | 68.21 | 67.98 | |

| VOTING | D | 77.5 | 75.61 | 76.54 |

| K | 76.43 | 73.62 | 75 | |

| E | 74.36 | 72.5 | 73.42 | |

| B | 77.16 | 76.69 | 76.92 |

| Target Data Set | Precision | Recall | F-Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| D | 65.07 | 63.76 | 64.41 |

| K | 63.89 | 62.16 | 63.01 |

| E | 67.11 | 66.23 | 66.67 |

| B | 63.38 | 60.81 | 62.07 |

| Size of Sample | B | D | E | K |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000 | 80.95 | 78.42 | 79.15 | 80.95 |

| 1500 | 82.36 | 80.24 | 81.66 | 82.36 |

| 2000 | 82.7 | 80.24 | 82.36 | 82.7 |

| 2500 | 83.39 | 80.95 | 80.24 | 83.39 |

| 3000 | 84.39 | 82.01 | 83.04 | 84.39 |

| 3500 | 85.39 | 83.04 | 84.06 | 85.39 |

| 4000 | 85.72 | 83.38 | 83.04 | 85.72 |

| 4500 | 82.95 | 78.42 | 81.79 | 80.16 |

| 5000 | 81.31 | 78.79 | 80.24 | 80.24 |

| 5500 | 80.24 | 77.68 | 79.16 | 78.05 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mohammed Almansor, M.A.; Zhang, C.; Khan, W.; Hussain, A.; Alhusaini, N. Cross Lingual Sentiment Analysis: A Clustering-Based Bee Colony Instance Selection and Target-Based Feature Weighting Approach. Sensors 2020, 20, 5276. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20185276

Mohammed Almansor MA, Zhang C, Khan W, Hussain A, Alhusaini N. Cross Lingual Sentiment Analysis: A Clustering-Based Bee Colony Instance Selection and Target-Based Feature Weighting Approach. Sensors. 2020; 20(18):5276. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20185276

Chicago/Turabian StyleMohammed Almansor, Mohammed Abbas, Chongfu Zhang, Wasiq Khan, Abir Hussain, and Naji Alhusaini. 2020. "Cross Lingual Sentiment Analysis: A Clustering-Based Bee Colony Instance Selection and Target-Based Feature Weighting Approach" Sensors 20, no. 18: 5276. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20185276

APA StyleMohammed Almansor, M. A., Zhang, C., Khan, W., Hussain, A., & Alhusaini, N. (2020). Cross Lingual Sentiment Analysis: A Clustering-Based Bee Colony Instance Selection and Target-Based Feature Weighting Approach. Sensors, 20(18), 5276. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20185276