5.1. Formal Analysis

Following References [

54,

55], the performance of the proposed protocol has been tested under the compromised conditions using AVISPA (

Automated

Validation of

Internet

Security

Protocols and

Applications). AVISPA is a security analyzer tool used to find vulnerabilities in the security protocols. It works on HLPSL (High Level Protocol Specification Language) and use an interpreter,

HLPSL2IF which translates HLPSL to an Intermediate Format (IF). IF is presented as an input to the various back ends of AVISPA (e.g., on-the-fly model-checker (OFMC), Constraint-Logic-based ATtack SEarcher (CL-AtSe), etc.). The back ends compile the results and declare the protocol as

safe or

unsafe. We intentionally omitted the detailed discussion on the back ends of AVISPA, interested readers may refer to Reference [

56].

The initial process is to script the subjected protocol into HLPSL language. The script begins with basic roles, followed by composition role, and ends with environment role. Basic roles declare the agents, crypto operations, compromised channel (dolev-yao), and various processes that are carried out locally by the agent. In contrast, composition roles declare the various legitimate entities that participate in the conversation. A very careful scripting of environment role is required as it may decide the effectiveness of this test. Environment role declares the global entities and constants. In addition, environment role describes the role and knowledge of intruder followed by various sessions that may exists during the communication. This role ends with the declaration of goals that defines the security attributes taken into consideration.

To assess the strength of the MAKE-IT protocol, the mutual authentication and key exchange phase has been scripted and examined on AVISPA. Note that notations used in HLPSL script is defined in

Table 2.

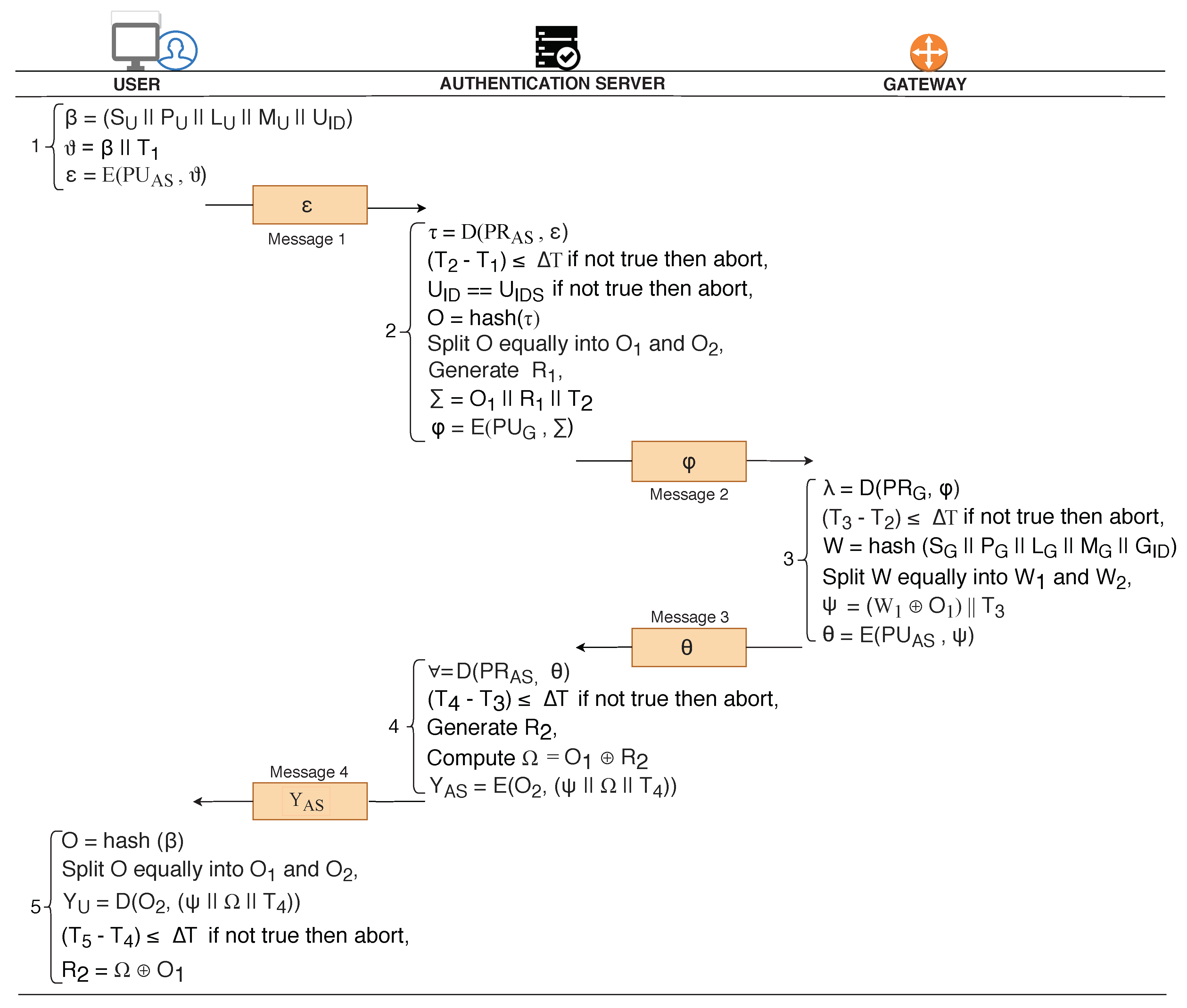

Initially basic roles of the

user and

are declared that comprises of local agents (

U,

), crypto operations (hash), description of keys (

,

, etc.) and details of the compromised channel (

dy) used for communication. Additionally, it describes the various local constants and messages used and exchanged during the conversation, respectively. User device gets activated in State = 0 (RCV(start)) whereas in State’:= 1 the user device generates a timestamp (

), and computes

. Afterwards, user computes

= {

and forms the message,

(=

). The goal predicates set by the

user is the privacy of the data

and

along with the validation of the timestamp

at

. The encrypted message (

) is sent to the

as shown in

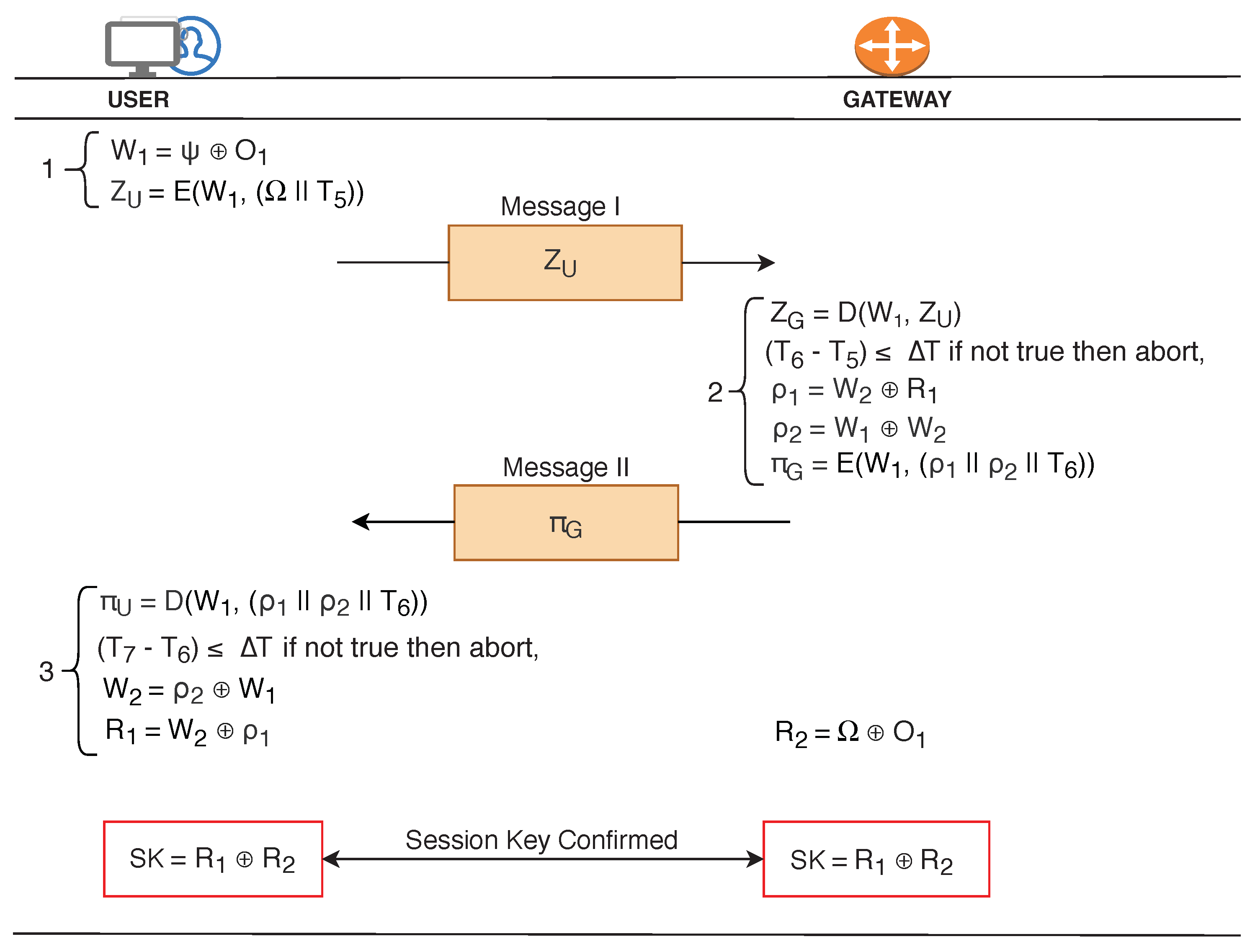

Figure 6.

receives the in State = 1 and begins processing in State:= 2. The foremost task performed by is the decryption of the received message, = {. Post decryption, gateway validates the timestamp (witness(,U,user_gateway_t5,)) to avoid replay attacks. Upon successful validation, computes (= (,)) and (= (,)). Subsequently, generates a fresh timestamp (), and computes = and compiles a message (= ). The goal predicates set by the is the privacy of the data and along with the validation of the timestamp at . Thereafter, send the message to the user for extracting the required information to generate secret keys. Consequently, decrypts the received message , = . Post decryption, validates the timestamp (witness(U,,gateway_user_t6,)). Successful decryption of and results in mutual authentication. Finally, user and use the retrieved information to generate the secret keys, .

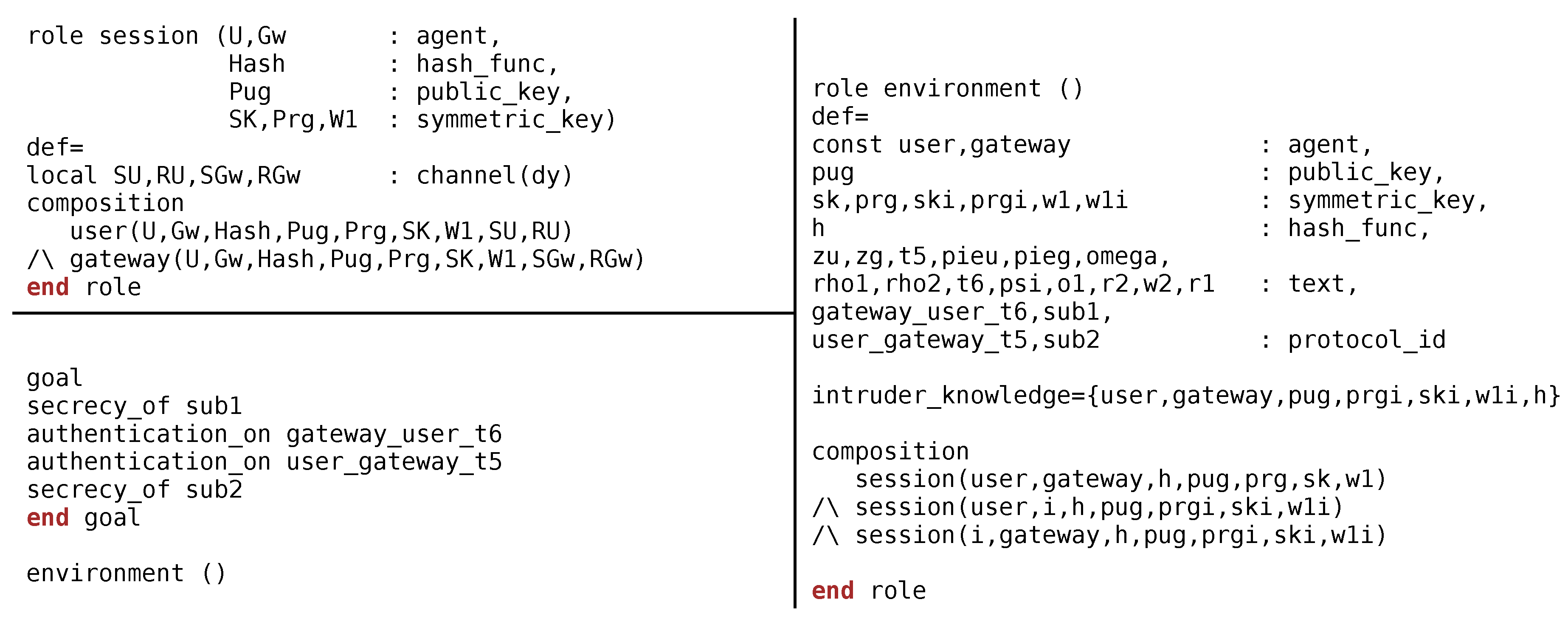

Session role demonstrates the various constants, variables used by the entities during the communication for example, User(U,,,,,,,,), (U,,,,,,, ,). On the contrary, environment role is very prominent as it describes the constants and variables used globally by the agents. Furthermore, it describes the behaviour of the {, ,,,,,h}. Environment role also discusses the organizations of various sessions that may takes place between legitimate and illegitimate entities, for example, (,,h,,,, ), (,i,h,,,,), (i,,h,,,,).

Finally, the environment role ends with declaration of goals of interest. The goals established to evaluate the robustness of proposed protocol is depicted in

Figure 7 and listed here:

Secrecy_of sub1 represents that {Omega; T5} are kept secret between user and gateway.

Authentication_on gateway_user_t6 states that the timestamp (i.e., ) of the message {} will be validated at the user.

Authentication_on user_gateway_t5 states that the timestamp (i.e., ) of the message will be validated at the .

Secrecy_of sub2 represents that {Rho1; Rho2} are kept secret between gateway and user.

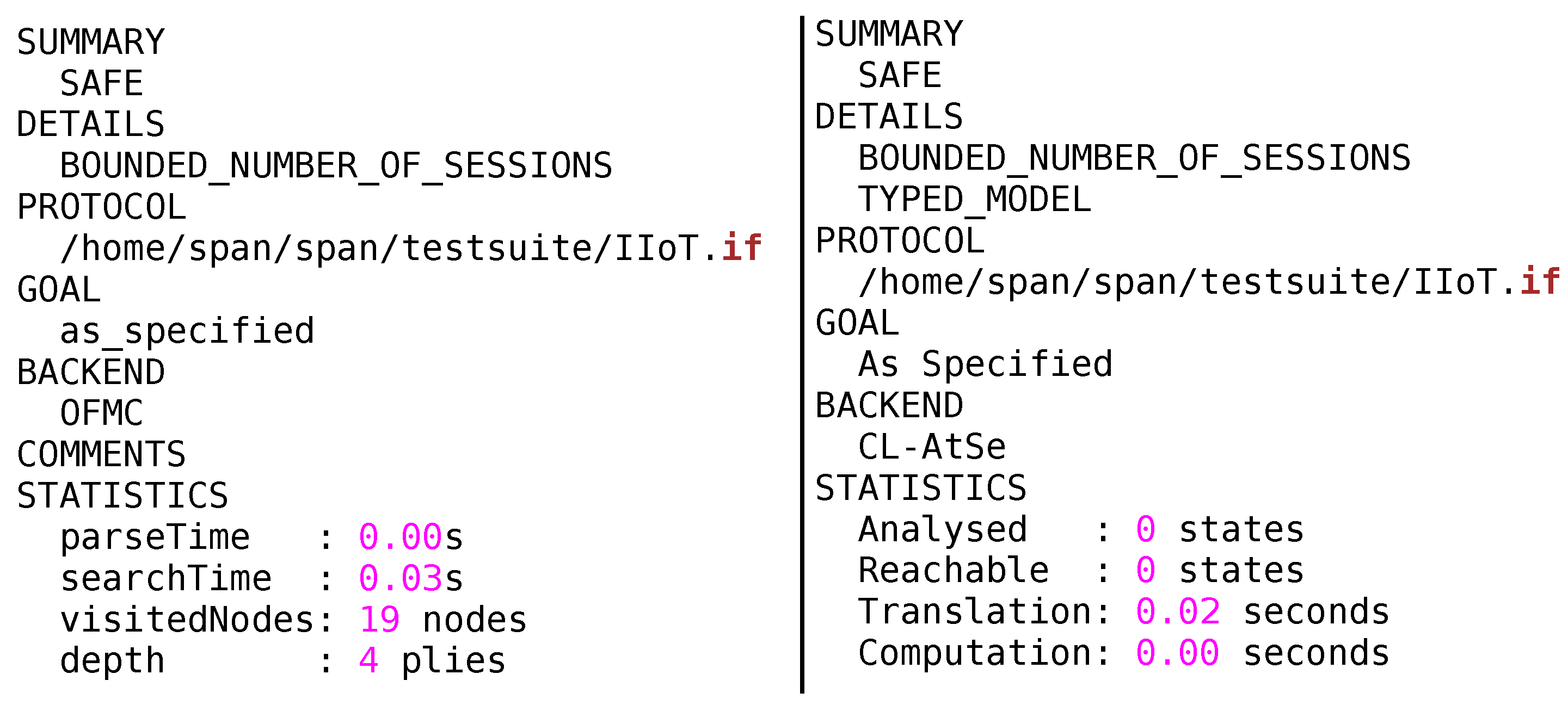

MAKE-IT approach has been tested on two back ends of AVISPA that is, OFMC and CL-AtSe as illustrated in

Figure 8. The Output file (OF) of OFMC and CL-AtSe backend clearly demonstrates that no vulnerability has been identified and the protocol is declared safe to use in Internet of Things applications. Conclusively, the protocol can withstand all the attacks mentioned in DY model while still maintaining the data privacy, authenticity and integrity of communications.

5.2. Informal Analysis

The informal security analysis of MAKE-IT approach has been discussed in this sub-section.

Theorem 1. Resistant to replay attacks.

Proof of Theorem 1. Freshness in each session is guaranteed as the messages () are composed of timestamps (). , , , , , and , are all embedded with timestamps , , , , , and , respectively. Any misuse of expired message can be easily traced, for example, − ≤ T. Assume an attacker eavesdropped the message, and replay later to for getting unauthorized access. The receives the replayed message and decrypts, , ( . Post decryption, verifies the timestamp and analyse that received message contains old and expired timestamp, − > T. The T is usually kept very small to make it difficult for the adversary to replay the captured messages within T. The instead of processing further discards the dishonest message. Additionally, the message is encrypted with the secret temporary session key , hence making it computationally infeasible for the adversary to modify the timestamp . Therefore, proposed protocol is resilient to replay attacks. □

Theorem 2. Resilient to man in the middle (MITM) attack.

Proof of Theorem 2. In MITM attack, adversary modifies the captured messages in such a way that destination cannot differentiate the modified message from the original message. Assume an attacker performs MITM attack between user and the gateway by capturing and modifying the message , ( . These computations are hard for attacker due to non availability of temporary secret key required for deciphering the captured message , ( followed by ciphering of modified message , ( . Therefore, attacker fails to attempt MITM attack between the user and the gateway. Similarly, other messages , , , , and are also encrypted and hence cannot be modified. Therefore, the proposed scheme is protected from MITM attacks. □

Theorem 3. Secured against modification attack.

Proof of Theorem 3. Integrity is preserved due to use of one way hash function (i.e., SHA), for example, the element O = hash () guarantees prevention against modification attacks. Any form of alterations in O can be easily identified during reconstruction and comparison of hash at other entity for example, == . Apart from one way hash functions, the messages exchanged are encrypted to ensure that integrity of the communication is retained. Assume if attacker captures the message , and tries to modify , . However, it is computationally difficult for the attacker to make any changes as the information is encrypted with the temporary secret key, . Neither the nor the security credentials (random secrets) are ever shared in plain text over the unsecured medium. Therefore, attacker does not find way to modify the content. Similarly, other messages , , , , and are ciphered to prevent modifications. Thus, proposed scheme is secured against modification attack. □

Theorem 4. Secure secret key generation.

Proof of Theorem 4. The proposed scheme ensures the secrecy during formation of secret key, . Secret key is formed using random secrets (, ) generated by trusted and tamper proof entity, . User shares with gateway through message . Likewise, gateway shares with user through . Both and user retrieve & from and , respectively. Finally, user and gateway generate a shared secret key, SK = ⊕. As the keys are formed using random secrets which were never shared with anyone, therefore proposed protocol adheres to security measures while forming the secret key. The compliance to security measures ensures that secret key generated is not compromised and can be used for securing future communications. □

Theorem 5. Proposed scheme exhibits data confidentiality.

Proof of Theorem 5. Revealing of information to untrusted entities can pose serious threats to the existence of IIoT networks. Assume an attacker eavesdrop a message, . In spite of successful eavesdropping, the attacker would not be able to interpret the information due to the non availability of the private key of AS, . The AS has never shared its private key with anyone, therefore, the attacker remains unsuccessful in obtaining the information from the captured message, . In another instance, lets assume that attacker has captured, , . The attacker has intentions to retrieve and from the captured message, . Despite the successful capturing of , the attacker would not be able to recover and from and , respectively as the attacker needs a temporary secret key to decipher the information , ; the temporary secret key is shared amongst legitimate entities only. Similarly, the messages , , , and are also encrypted, therefore, confidentiality of the information is ensured at all levels of communication. The attacker does not have these keys, , , , and , to recover the overall information exchanged between the IIoT network entities. The proposed scheme exhibits the security property of data confidentiality. □

Theorem 6. MAKE-IT achieves identity anonymity.

Proof of Theorem 6. Identity anonymity is desirous to prevent the network from flooding based attacks, location aware attacks, and impersonation attacks, and so forth. MAKE-IT never discloses the identities of the network nodes to any unauthorized entity. Only has prepared an offline database of identities for verification purposes. is a trusted entity and stores the information in tamper proof memory, therefore any access or modification by the attacker is not possible. Even the parties involved in the communication does not know the real identities of each other, their identity details are hashed before being shared. Consider an attacker intercepted the message = , ) containing the hashed identity details of the , still the attacker would not be able to interpret the identity due to hashing (W = hash ( )) and ciphering of information, . The attacker does not have the private key of to decipher the information. Therefore, MAKE-IT keeps the communication anonymous by not revealing the identities of , , and during the exchange of messages. □