Structure of Fungal Communities in Sub-Irrigated Agricultural Soil from Cerrado Floodplains

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

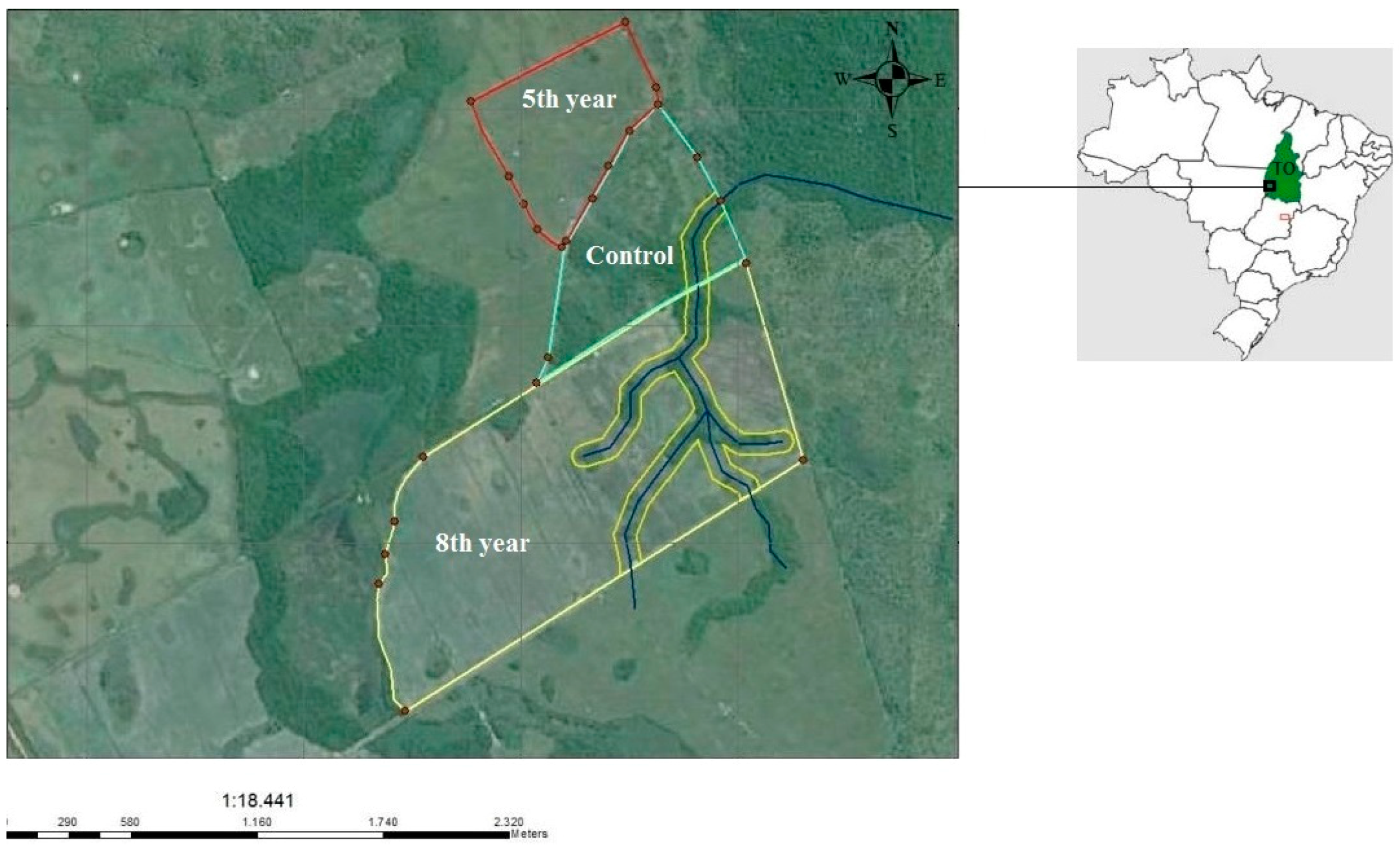

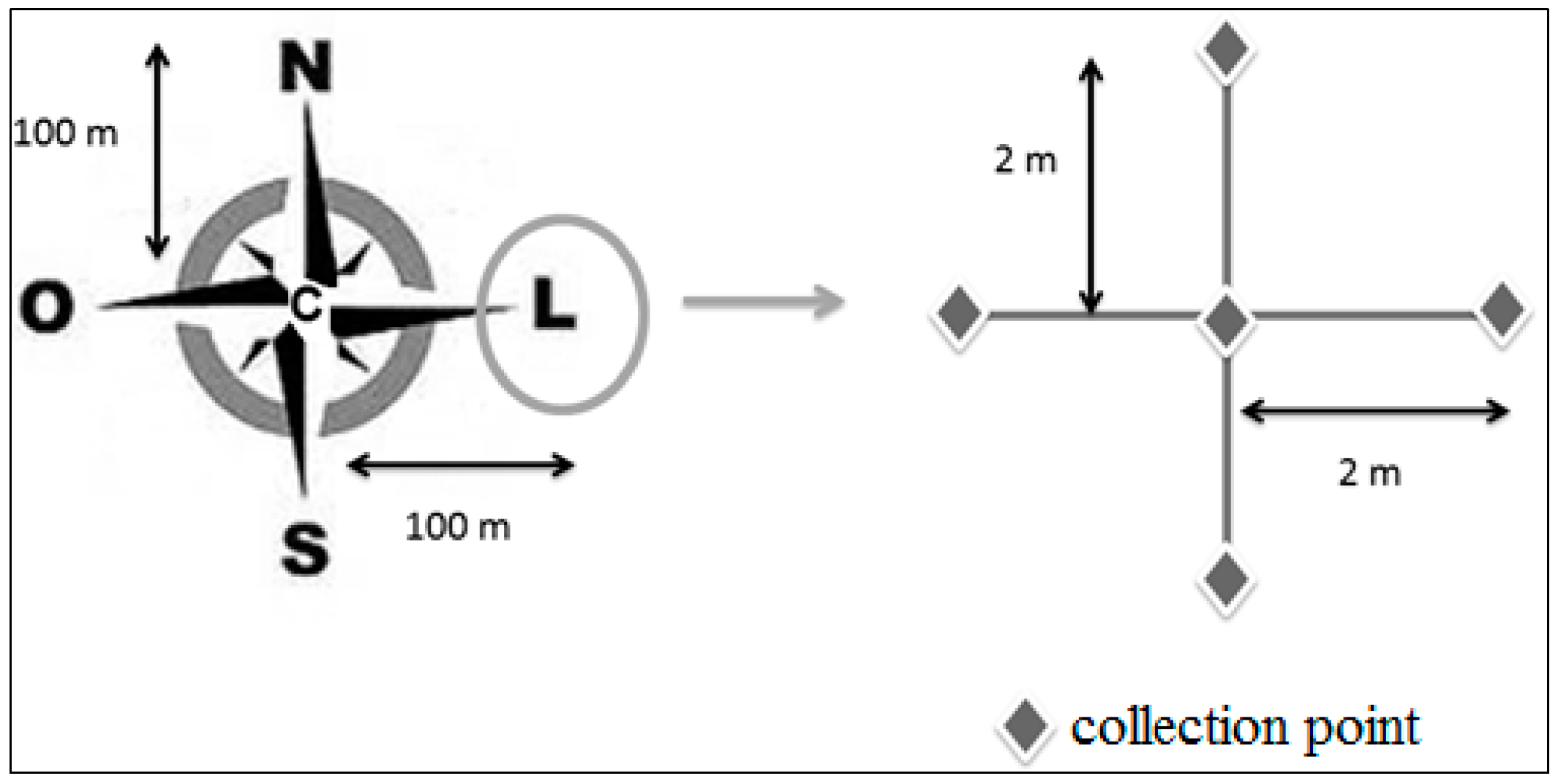

2.1. Study Areas and Soil Sampling

2.2. Soil Chemical Characteristics and Statistical Analysis

2.3. Genomic DNA Extraction and PCR-ARISA of the 18S-28S Ribosomal Intergenic Spacer

2.4. Automated Analysis of the 18S-28S Ribosomal Intergenic Spacer

2.5. Statistical Analysis of the Data Obtained Using ARISA Technique

3. Results and Discussion

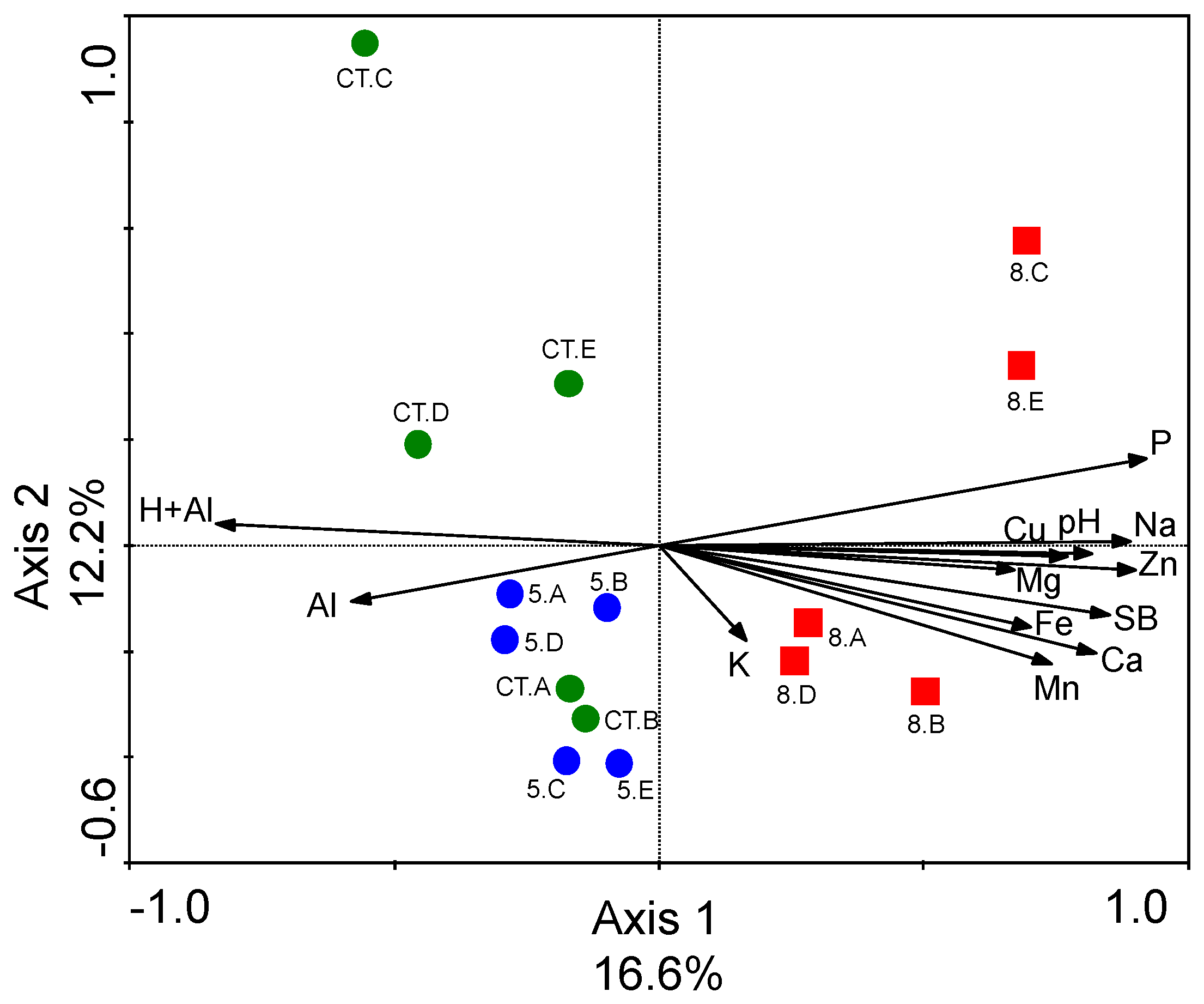

3.1. Differences in Soil Chemical Characteristics

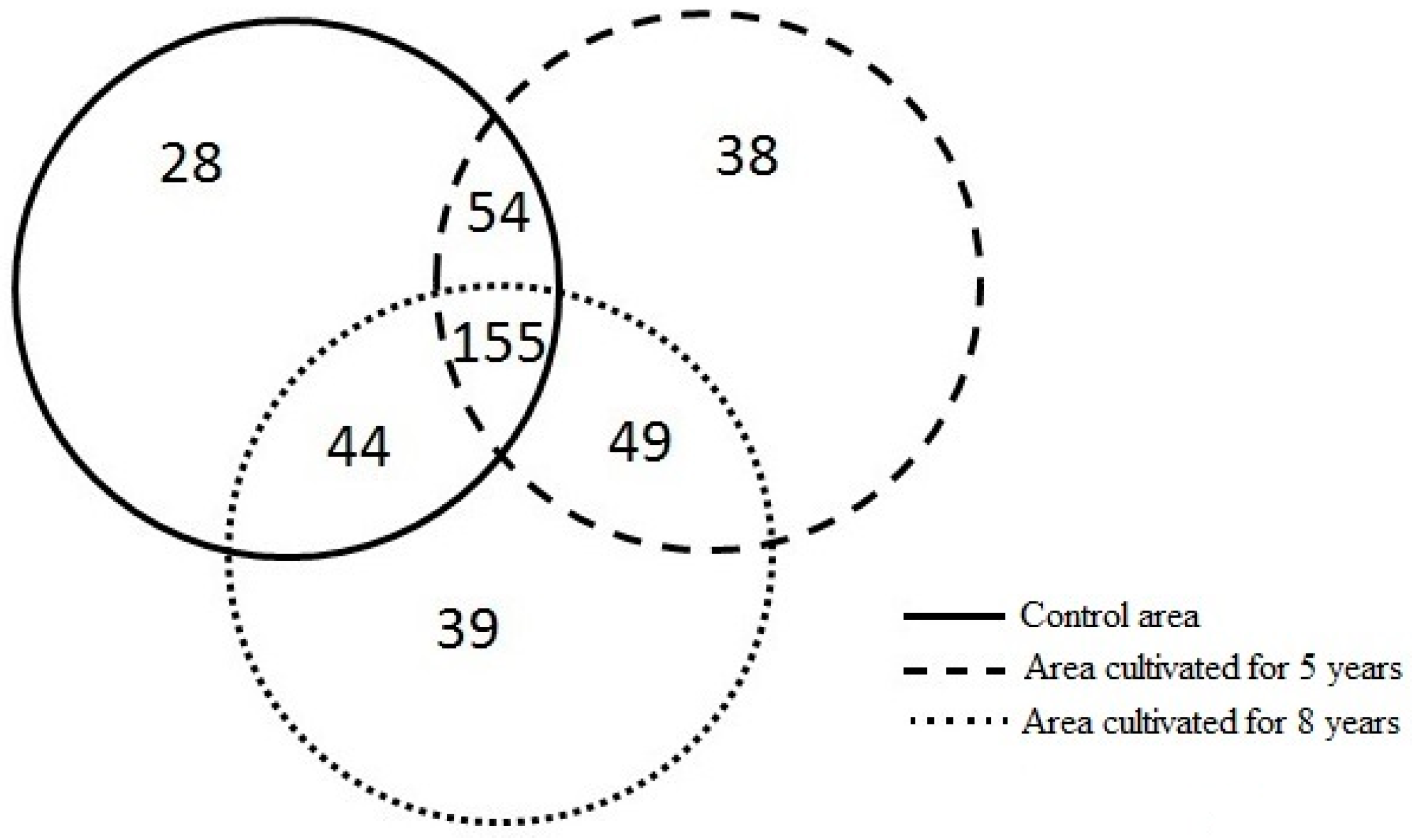

3.2. Differences in Richness and Abundance of Phylotypes in the Soil Fungal Microbial Communities

3.3. Differences in Soil Fungal Microbial Community Structures

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Satish, N.; Sultana, S.; Nanjundiah, V. Diversity of soil fungi in a tropical deciduous forest in Mudumalai, southern India. Curr. Sci. 2007, 93, 669–677. [Google Scholar]

- Bills, G.F.; Christensen, M.; Powell, M.; Thorn, G. Saprobic soil fungi. In Biodiversity of Fungi: Inventory and Monitoring Methods; Mueller, G.M., Bills, G.F., Foster, M.S., Eds.; Elsevier: Burlington, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 271–302. [Google Scholar]

- Treseder, K.K. Nutrient acquisition strategies of fungi and their relation to elevated atmospheric CO2. In The Fungal Community: Its Organization and Role in the Ecosystem; Dighton, J., White, J.F., Oudemans, P, Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Ration, FL, USA, 2005; pp. 713–731. [Google Scholar]

- Watling, R. Fungal conservation: Some impressions–A personal view. In The Fungal Community: Its Organization and Role in the Ecosystem; Dighton, J., White, J.F., Oudemans, P., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Ration, FL, USA, 2005; pp. 881–896. [Google Scholar]

- Miransari, M. Contribution of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis to plant growth under different types of soil stress. Plant Biol. 2010, 12, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, E.A.; Goedert, W.J.; Souza, D.M.G. Qualidade de solo submetido a sistemas de cultivo com preparo convencional e plantio direto. Pesqui. Agropecu. Bras. 2006, 41, 1185–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, M.A.C.; Souza, E.D.; Reis, E.F.; Pereira, H.S.; Azevedo, W.R. Atributos físicos, químicos e biológicos de solo de Cerrado sob diferentes sistemas de uso e manejo. Revista Bras. Ciênc. Solo 2009, 33, 147–157. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, M.J.; Muzilli, O. Características físicas de um Latossolo Vermelho-Escuro sob diferentes sistemas de manejo. Pesqui. Agropecu. Bras. 1984, 19, 873–882. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, A.P.; Quirino, B.F.; Pappas, G., Jr.; Kurokawa, A.S.; Neto, E.L.; Kruger, R.H. Diversity of soil fungal communities of Cerrado and its closely surrounding agriculture fields. Arch. Microbiol. 2008, 190, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, A.P.; Silva, M.R.S.S.; Quirino, B.F.; Bustamante, M.M.C.; Krüger, R.H. Microbial diversity in cerrado biome (Neotropical savanna) soils. PLoS ONE 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresolin, J.D.; Bustamante, M.M.C.; Krüger, R.H.; Silva, M.R.S.S.; Perez, K.S. Structure and composition of bacterial and fungal community in soil under soybean monoculture in the brazilian cerrado. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2010, 41, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O´Brien, H.E.; Parrent, J.L.; Jackson, J.A.; Moncalvo, J.M.; Vilgalys, R. Fungal community analisys by large-scale sequencing of environmental samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 5544–5550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, M.M.; Triplett, E.W. Automated approach for ribosomal intergenic spacer analysis of microbial diversity and its application to freshwater bacterial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 4630–4636. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ranjard, L.; Poly, F.; Lata, J.C.; Mougel, C.; Thioulouse, J.; Nazaret, S. Characterization of bacterial and fungal soil communities by automated ribosomal intergenic spacer analysis fingerprints: Biological and methodological variability. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 4479–4487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lejon, D.P.H.; Chaussod, R.; Ranger, J.; Ranjard, L. Microbial community structure and density under different tree species in an acid forest soil (Morvan, France). Microb. Ecol. 2005, 50, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarrete, A.A.; Cannavan, F.S.; Taketani, R.G.; Tsai, S.M. A molecular survey of the diversity of microbial communities in different Amazonian agricultural model systems. Diversity 2010, 2, 787–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouquet, P.; Maron, P.A.; Nowak, V.; Duc, T.T. Utilization of microbial abundance and diversity as indicators of the origin of soil aggregates produced by earthworms. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2013, 57, 950–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiten, G. Vegetation near Santa Teresinha, NE Mato Grosso. Acta Amazon. 1985, 15, 275–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kichel, E.; Fidelis, R.R.; dos Santos, M.M.; Brandão, D.R.; Cancellier, E.L.; do Nascimento, I.R. Efeito do Nitrogênio em genótipos de arroz cultivados em várzea úmida do Estado do Tocantins. Rev. Ceres 2011, 58, 84–89. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mileski, E. Aspecto da vegetação e do ecossistema da Ilha do bananal. In Mapa Fitoecológico e Indicadores da Pressão Antrópica; Secretária de Assuntos Estratégicos: Brasília, Brazil, 1994; p. 104. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Embrapa. Manual de Métodos de Análise de Solos; Embrapa Solos: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2011; p. 230. Available online: https://www.embrapa.br/busca-de-publicacoes/-/publicacao/990374/manual-de-metodos-de-analise-de-solo (accessed on 10 March 2016). (In Spanish)

- Brody, J.R.; Kern, S.E. Sodium boric acid: Atriz-less, cooler conductive medium for DNA electrophoresis. BioTechniques 2004, 36, 214–216. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Culman, S.W.; Gauch, H.G.; Blackwood, C.B.; Thies, J.E. Analysis of T-RFLP data using analysis of variance and ordination methods: A comparative study. J. Microbiol. Methods 2008, 75, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mucha, A.P.; Teixeira, C.; Reis, I.; Magalhães, C.; Bordalo, A.A.; Almeida, C.M.R. Response of a salt marsh microbial community to metal contamination. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2013, 130, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindt, R.; Coe, R. A manual and software for common statistical methods and biodiversity studies. In Tree Diversity Analysis; World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF): Nairobi, Kenya, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ernani, P.R.; Ribeiro, M.F.S.; Bayer, C. Chemical modifications caused by liming below the limed layer in a predominantly variable charge acid soil. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2004, 35, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caires, E.F.; Garbuio, F.J.; Churka, S.; Barth, G.; Corrêa, J.C.L. Effects of soil acidity amelioration by surface liming on no-till corn, soybean, and wheat root growth and yield. Eur. J. Agron. 2008, 28, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.; Fageria, N.K. Liming influence on soil chemical properties, nutritional status and yield of alfalfa grown in acid soil. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Solo 2010, 34, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, D.H.; Schmidt, T.M. Diversity and dynamics of microbial communities in soils from agro-ecosystems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 5, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambelli, A.; Persiani, A.M.; Maggi, O.; Lunghini, D.; Onofri, S.; Riess, S.; Dowgiallo, G.; Puppi, G. Comparative studies on microfungi in tropical ecosystems. In Mycological Studies in South Western Ivory Coast Forest; Report No. 1; MAB, UNESCO: Paris, France, 1983; p. 102. [Google Scholar]

- Maggi, O.; Persiani, A.M.; Casado, M.A.; Pineda, F.D. Edaphic mycoflora recovery in tropical forests after shifting cultivation. Acta Oecol. 1990, 11, 337–350. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, K.R.; Gorley, R.N. PRIMER 6.0: User Manual/Tutorial; PRIMER-E: Plymouth, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hitzl, W.; Henrich, M.; Kessel, M.; Insam, H. Application of multivariate analysis of variance and related techniques in soil studies with substrate utilization tests. J. Microbiol. Methods 1997, 30, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. Microbial ecology in the age of genomics and metagenomics: concepts, tools, and recent advances. Mol. Ecol. 2006, 15, 1713–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramette, A. Multivariate analyses in microbial ecology. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2007, 62, 142–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Chemical Properties | Study Areas | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Native Vegetation (Control Area) | Area Cultivated for Five Years | Area Cultivated for Eight Years | |

| pH | 4.4 (1) c (2) ± 0.11 (3) | 4.6 b ± 0.08 | 5.0 a ± 0.07 |

| OM | 89.6 a ± 16.78 | 86.6 a ± 11.82 | 60.2 a ± 20.37 |

| P | 8.8 b ± 0.97 | 20.2 a ± 7.67 | 46.3 a ± 11.78 |

| S | 3.1 a ± 0.32 | 3.8 a ± 0.43 | 3.4 a ± 1.06 |

| K | 46.6 b ± 8.29 | 94.8 a ± 35.40 | 75.8 a,b ± 16.85 |

| Ca | 0.68 c ± 0.53 | 1.92 b ± 0.41 | 3.5 a ± 0.46 |

| Mg | 0.76 b ± 0.59 | 0.92 b ± 0.08 | 1.8 a ± 0.33 |

| Al | 1.04 a ± 0.41 | 0.5 b ± 0.45 | 0.28 b ± 0.04 |

| H + Al | 10.0 a ± 1.20 | 8.8 a ± 0.45 | 7.2 b ± 0.56 |

| CEC | 11.55 a ± 1.33 | 11.92 a ± 0.17 | 12.77 a ± 0.89 |

| SB | 13.38 c ± 6.21 | 25.84 b ± 3.69 | 43.62 a ± 2.41 |

| Na | 21.2 b ± 4.14 | 19.6 b ± 1.67 | 29.6 a ± 2.96 |

| Zn | 0.78 c ± 0.82 | 4.0 b ± 0.88 | 8.1 a ± 1.60 |

| B | 0.22 a ± 0.05 | 0.19 a ± 0.03 | 0.23 a ± 0.05 |

| Cu | 1.2 b ± 0.46 | 2.1 a,b ± 0.58 | 3.22 a ± 1.00 |

| Fe | 47.84 b ± 12.27 | 73.16 a,b ± 13.63 | 86.78 a ± 20.18 |

| Mn | 9.2 b ± 3.4 | 18.8 a ± 3.65 | 23.84 a ± 3.32 |

| Study Areas | Sampling Site in Each Area | Number of Phylotypes in Each Sampling Site | Total Number of Phylotypes * | Number of Phylotypes with Abundance Levels < 1% | Number of Phylotypes with Abundance Levels > 1% | Number of Phylotypes with Abundance Levels > 1% Shared Between the Control Area and the Area Cultivated for Five Years | Number of Phylotypes with Abundance Levels > 1% Shared Between the Control Area and the Area Cultivated for Eight Years | Number of Phylotypes with Abundance Levels > 1% Shared Between the Area Cultivated for Five and Eight Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control area | A | 102 | 281 | 255 | 26 | 5 | 0 | 2 |

| B | 126 | |||||||

| C | 76 | |||||||

| D | 86 | |||||||

| E | 115 | |||||||

| Area cultivated for 5 years | A | 98 | 296 | 273 | 23 | |||

| B | 88 | |||||||

| C | 123 | |||||||

| D | 144 | |||||||

| E | 118 | |||||||

| Area cultivated for 8 years | A | 94 | 287 | 270 | 17 | |||

| B | 98 | |||||||

| C | 104 | |||||||

| D | 149 | |||||||

| E | 156 |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oliveira, E.C.A.M.; Navarrete, A.A.; Peluzio, J.M.; De Oliveira Junior, W.P.; Valadares, A.D.A.; Tsai, S.M.; Morais, P.B.d. Structure of Fungal Communities in Sub-Irrigated Agricultural Soil from Cerrado Floodplains. Diversity 2016, 8, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/d8020013

Oliveira ECAM, Navarrete AA, Peluzio JM, De Oliveira Junior WP, Valadares ADA, Tsai SM, Morais PBd. Structure of Fungal Communities in Sub-Irrigated Agricultural Soil from Cerrado Floodplains. Diversity. 2016; 8(2):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/d8020013

Chicago/Turabian StyleOliveira, Elainy Cristina A. M., Acacio A. Navarrete, Joenes M. Peluzio, Waldesse P. De Oliveira Junior, Alana De A. Valadares, Siu M. Tsai, and Paula B. de Morais. 2016. "Structure of Fungal Communities in Sub-Irrigated Agricultural Soil from Cerrado Floodplains" Diversity 8, no. 2: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/d8020013

APA StyleOliveira, E. C. A. M., Navarrete, A. A., Peluzio, J. M., De Oliveira Junior, W. P., Valadares, A. D. A., Tsai, S. M., & Morais, P. B. d. (2016). Structure of Fungal Communities in Sub-Irrigated Agricultural Soil from Cerrado Floodplains. Diversity, 8(2), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/d8020013