Differences in Manioc Diversity Among Five Ethnic Groups of the Colombian Amazon

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Manioc Diversity in the Study Area

2.1.1. Morphotypic Manioc Diversity

| Maniocinventory San Martín de Amacayacu (Tikuna) | Manioc inventory communities “People of the Center” | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aduche (Andoke) | Guacamayo (Uitoto) | Peña Roja (Nonuya) | Villazul (Muinane) | ||||||

| Maniocs “to eat” | Total | 23 (70%) | Manicuera | Total | 2 (6%) | 3 (9%) | 2 (4%) | 2 (7%) | 60 |

| EI | 2 | 3 | 2 | 211 | |||||

| EI | 10 | NE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Maniocs “to eat” | Total | 9 (28%) | 8 (23%) | 4 (9%) | 7 (27%) | ||||

| NE | 13 | EI | 8 | 0 | 0 | 11 | |||

| NE | 1 | 8 | 4 | 6 | |||||

| Bitter maniocs | Total | 10 (30%) | Maniocs “to grate” | Total | 18 (57%) | 14 (40%) | 25 (54%) | 16 (59%) | 113 |

| EI | 14 | 0 | 52 | 21 | |||||

| EI | 0 | NE | 4 | 14 | 20 | 14 | |||

| Yellow bitter maniocs | Total | 3 (9%) | 10 (28%) | 15 (33%) | 2 (7%) | ||||

| NE | 10 | EI | 3 | 1 | 22 | 11 | |||

| NE | 0 | 9 | 13 | 1 | |||||

| Total | 33 | 32 | 35 | 46 | 27 | 173 | |||

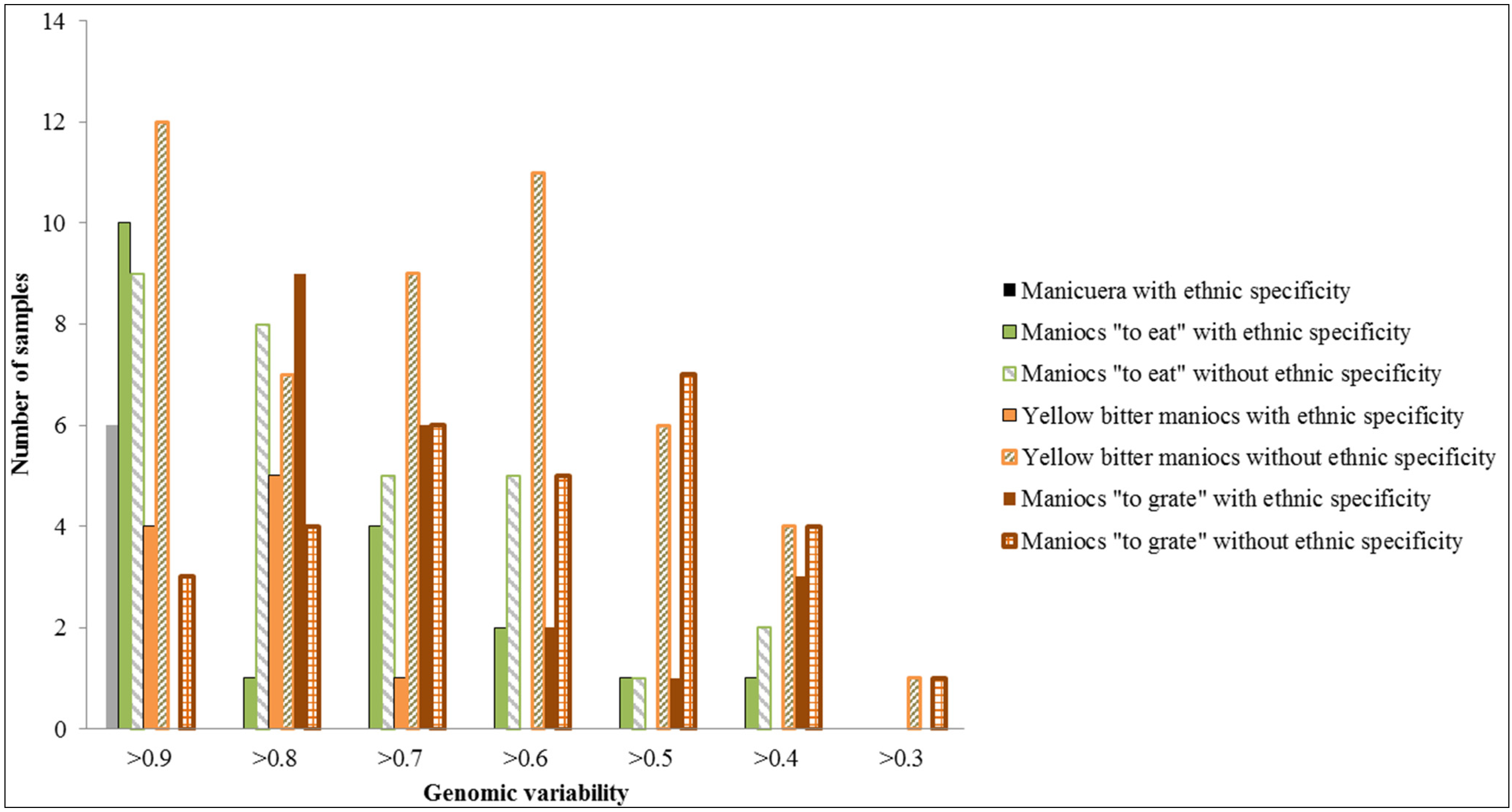

2.1.2. Genotypic Manioc Diversity

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| z-value obtained | 3.27 | 1.96 | 1.52 | 1.09 | 1.09 | −0.21 | −0.65 | −1.09 | −1.52 | −1.96 | −2.40 | −2.40 |

| z-value expected (two-tailed 95% confidence interval) | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.40 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.60 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Duplicates | Duplicates among Communities | |||||||||||

| 1.(ADU10, GUO18, GUO22) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2. (ADU16,GUO6, AMA1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3. (ADU1, GUO29) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 4. (ADU11, GUO13) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5. (ADU18, GUO4) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 6. (ADU23, GUO8) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 7. (ADU30, GUO10) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8. (AMA28, GUO9) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 9. (GUO31, PRO23) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 10. (PRO2, VA12) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 11. (PRO21, VA24) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12. (PRO40, VA19) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 13. (PRO42, VA11) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 14. (PRO8,VA23) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Duplicates | Duplicates within Communities | |||||||||||

| 15. (ADU32, ADU27) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 16. (ADU3,ADU4) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 17. (AMA7, AMA17) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 18. (AMA3, AMA30) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 19. (AMA31, AMA32) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 20. (PRO9, PRO47) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 21. (VA13,VA15) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

2.2. Sources of Manioc Landraces

2.2.1. Mythical Accounts of the Origin of Manioc Use

“When God started to distribute the manioc landraces among the People of the Center, he first distributed Manicuera among all groups. Then he distributed maniocs “to grate” to Andoke, Muniane and Bora people. It was getting late and there were still other groups waiting for maniocs. He finally gave to Uitoto and Nonuya people yellow bitter maniocs. Because it was too late to grate them, Uitoto and Nonuya women put the roots into the water. That is why Uitoto and Nonuya women don’t know how to grate manioc”.(Interview with V.M., April 25, 2013)

2.2.2. Sources of Today’s Manioc Inventories

2.3. The Effect of Different Soil Environments on Manioc Diversity

2.4. The Effect of Manioc Exchange on Manioc Diversity

2.5. Indigenous Culinary Traditions

| Ethnic Preparations | A | M | N | T | U |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Based on Manicuera maniocs | |||||

| Manicuera (Manioc grated and boiled for a sweet manioc juice) | A | M | N | U | |

| Based on maniocs “to eat” | |||||

| Arapata (Manioc cooked and mixed with banana) | T | ||||

| Colada (Manioc starch cooked with water and sugar) | X | ||||

| Dry casabe (Round bread made from the manioc root) | X | ||||

| Farinha (A granulate of fermented and roasted manioc) | T | ||||

| Jutiroi (Juice of fermented manioc leaves boiled) | U | ||||

| Manioc juice boiled with fish | X | X | X | X | |

| Masato (Manioc beer obtained from a mix of mashed manioc and sweet potatoes) | T | ||||

| Monegú (Boiled manioc and kneaded with fish) | T | ||||

| Payavarú (Boiled manioc, mixed with toasted manioc leaves and squeezed) | T | ||||

| Payavarú wine (Fermented Payavarú) | T | ||||

| Pururuca (Masato with banana) | T | ||||

| Starch casabe (Round bread made of manioc starch) | X | ||||

| Tapioca (A granulate of toasted manioc starch) | T | ||||

| Unchará (Manioc bread) | T | ||||

| Based on maniocs “to grate” | |||||

| Arepa (Baked round bread) | X | X | X | X | |

| Caguana (Boiled starch and mixed with fruit juice) | A | M | X | X | |

| Colada | X | ||||

| Farinha | X | X | X | ||

| Manioc juice boiledwith fish | X | X | X | X | |

| Starch casabe | A | M | |||

| Tamal (Manioc root packed in banana leaves and steamed) | X | X | X | X | |

| Tapioca | X | ||||

| Based on yellow bitter maniocs | |||||

| Arepa | X | X | X | X | |

| Caguana | X | X | N | U | |

| Colada | X | ||||

| Dry casabe | N | U | |||

| Manioc juice boiled with fish | X | X | X | X | |

| Farinha | X | X | X | X | X |

| Tucupí (Source made cooking the fermented bitter manioc juice with hot chilies) | X | X | X | X | U |

| Jukui (Tucupí with fish and/or shrimps) | U | ||||

| Mingao (farinha mixed and water) | X | ||||

| Starch casabe | X | ||||

| Tapioca | X | ||||

| Tamal | X | X | X | X |

3. Discussion

3.1. Manioc Diversity and Manioc Classification in Indigenous Communities of the Colombian Amazon

3.2. Sources of Manioc Variability among Ethnic Groups

3.3. Sources of Manioc Variability among Communities

4. Conclusions

5. Materials and Methods

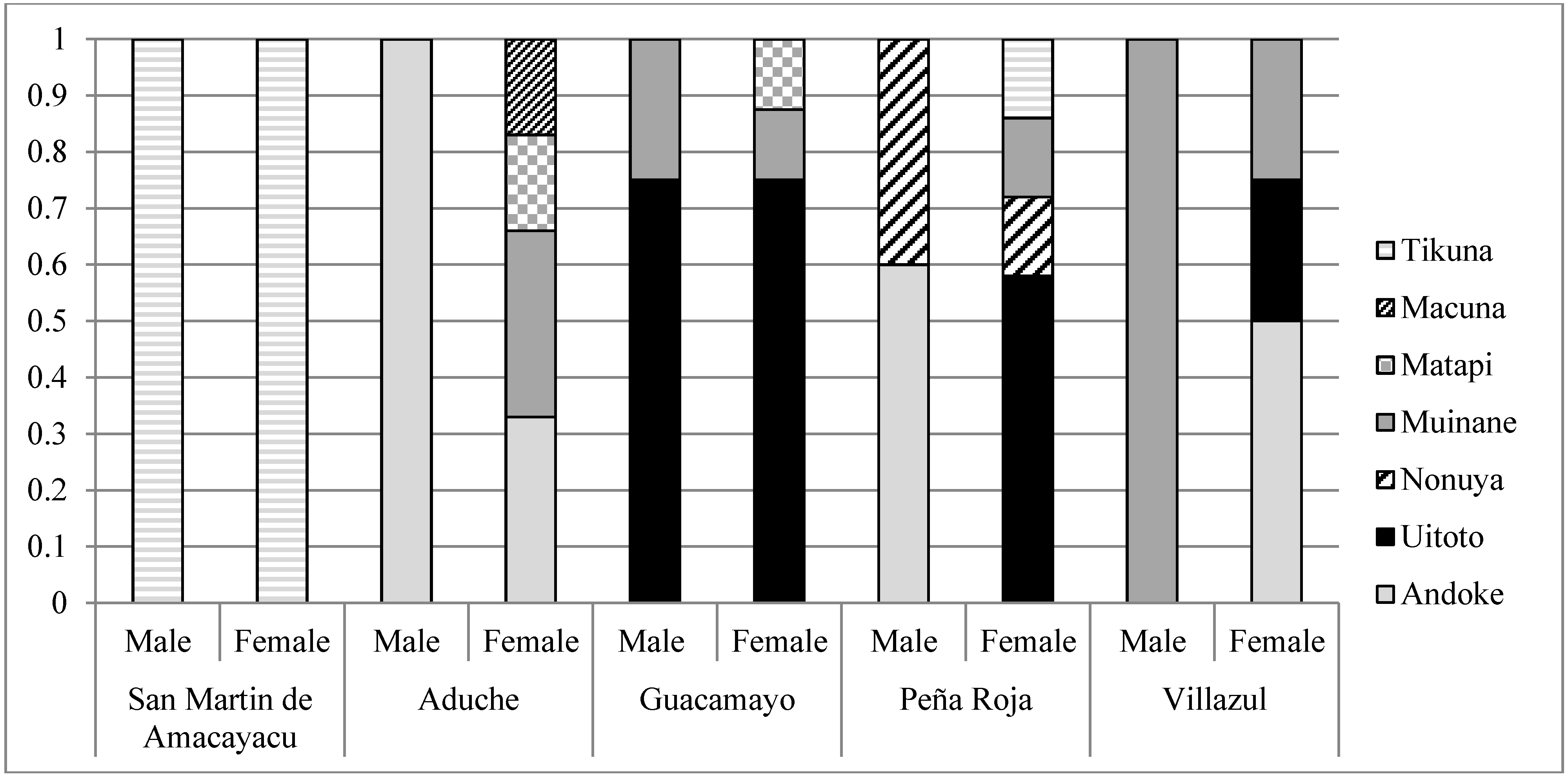

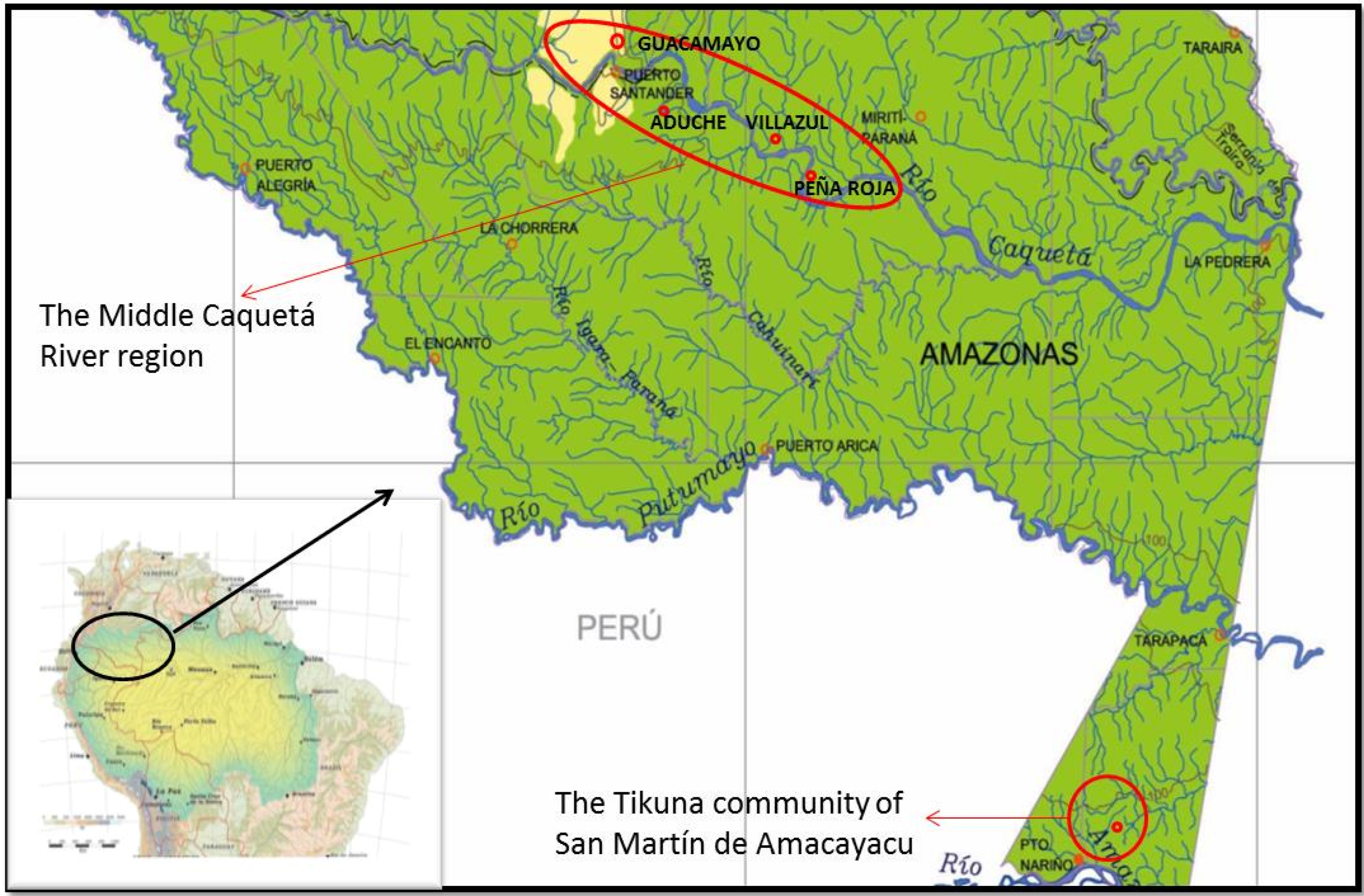

5.1. Study Area

5.2. Fieldwork

5.3. Populations

5.4. Ethnobotanical Data

5.4.1. Manioc Inventories

5.4.2. Inventory of Ethnic Manioc Dishes

5.5. Genetic Data

5.6. Statistical Analysis

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olsen, K.M.; Schaal, B.A. Evidence on the origin of cassava: Phylogeography of manihot esculenta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 5586–5591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sharkawy, M.A. Cassava biology and physiology. Plant Mol. Biol. 2004, 56, 481–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sharkawy, M.A. International research on cassava photosynthesis, productivity, eco-physiology, and responses to environmental stresses in the tropics. Photosynthetica 2006, 44, 481–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.H.D. Core collections: A practical approach to genetic resources management. Genome 1989, 31, 818–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, M.; Panaud, O.; Robert, T. Assessment of genetic variability in a traditional cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) farming system, using AFLP markers. Heredity 2000, 85, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, M.; McKey, D.; Panaud, O.; Anstett, M.C.; Robert, T. Traditional management of cassava morphological and genetic diversity by the Makushi Amerindians (Guyana, South America): Perspectives for on-farm conservation of crop genetic resources. Euphytica 2001, 120, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, M.; Mühlen, G.S.; McKey, D.; Roa, A.C.; Tohme, J. Genetic diversity of traditional South American landraces of cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz): An analysis using microsatellites. Econ. Bot. 2004, 58, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emperaire, L.; Peroni, N. Traditional management of agrobiodiversity in Brazil: A case study of manioc. Hum. Ecol. 2007, 35, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, J.A. Caboclo horticulture and Amazonian dark earths along the middle Madeira River, Brazil. Hum. Ecol. 2010, 38, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boster, J.S. Exchange of varieties and information between Aguaruna manioc cultivators. Am. Anthropol. New Ser. 1986, 88, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salick, J.; Cellinese, N.; Knapp, S. Indigenous diversity of cassava: Generation, maintenance, use and loss among the Amuesha, Peruvian upper Amazon. Econ. Bot. 1997, 51, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeven, A.C. Landraces: A review of definitions and classifications. Euphytica 1998, 104, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, T.C.C.; Maxted, N.; Scholten, M.; Ford-Lloyd, B. Defining and identifying crop landraces. Plant Genet. Resour. 2006, 3, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbi, I.Y.; Kulembeka, H.P.; Masumba, E.; Marri, P.R.; Ferguso, M. An est-derived SNP and SSR genetic linkage map of cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2012, 125, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, M.E.; Hearne, S.J.; Close, T.J.; Wanamaker, S.; Moskal, W.A.; Town, C.D.; de Young, J.; Marri, P.R.; Rabbi, I.Y.; de Villiers, E.P. Identification, validation and high-throughput genotyping of transcribed gene SNPs in cassava. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2012, 124, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKey, D.; Cavagnaro, T.R.; Cliff, J.; Gleadow, R. Chemical ecology in coupled human and natural systems: People, manioc, multitrophic interactions and global change. Chemoecology 2010, 20, 109–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujol, B.T.; Renoux, F.O.; Elias, M.; Rival, L.; Mckey, D. The unappreciated ecology of landrace populations: Conservation consequences of soil seed banks in cassava. Biol. Conserv. 2007, 136, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves-Pereira, A.; Peroni, N.; Abreu, A.G.; Gribel, R.; Clement, C.R. Genetic structure of traditional varieties of bitter manioc in three soils in Central Amazonia. Genetica 2011, 139, 1259–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, J.A.; Alves-Pereira, A.; Junqueira, A.B.; Peroni, N.; Clement, C.R. Convergent adaptations: Bitter manioc cultivation systems in fertile anthropogenic dark earths and floodplain soils in central Amazonia. PLoS One 2012, 7, e43636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heckler, S.; Zent, S. Piaroa manioc varietals: Hyperdiversity or social currency? Hum. Ecol. 2008, 36, 679–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duputié, A.; Massol, F.; David, P.; Haxaire, C.; McKey, D. Traditional amerindian cultivators combine directional and ideotypic selection for sustainable management of cassava genetic diversity. J. Evol. Biol. 2009, 22, 1317–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pujol, B.; Mühlen, G.; Garwood, N.; Horoszowski, Y.; Douzery, E.J.P.; McKey, D. Evolution under domestication: Contrasting functional morphology of seedlings in domesticated cassava and its closest wild relatives. New Phytol. 2005, 166, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKey, D.; Elias, M.; Pujol, B.; Duputié, A. The evolutionary ecology of clonally propagated domesticated plants. New Phytol. 2010, 186, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias, J.C.; Aguila, L.R.D.; Huaines, F.; Acosta, L.E.; Camacho, H.A.; Marín, Z.Y. Diversidad de Yucas Entre los Ticuna: Riqueza Cultural y Genética de un Producto Tradicional; Instituto Amazónico de Investigaciones Científicas Sinchi: Bogotá, Colombia, 2004; p. 32. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Acosta, L.E.; Mazorra, A. Enterramientos de Masas de Yuca del Pueblo Ticuna: Tecnología Tradicional en la Várzea del Amazonas Colombiano; Instituto Amazónico de Investigaciones Científicas, Sinchi: Leticia, Colombia, 2004; p. 109. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Camacho, H. Màgutá. La Gente Pescada por Yoí. Colcultura Premios Nacionales 1994; Colcultura: Bogotá, Colombia, 1995. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Peña-Venegas, C.P.; Stomph, T.J.; Verschoor, G.; Echeverri, J.A.; Struik, P.C. Classification and use of natural and anthropogenic soils by indigenous communities of the upper Amazon region of Colombia. Hum. Ecol. 2015, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen, M.C.V.D. La Dinámica de la Chagra; Corporación Araracuara: Bogotá, Colombia, 1984. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson, M.; Rosenberg, N.A. Clumpp: A cluster matching and permutation program for dealing with label switching and multimodality in analysis of population structure. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 1801–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, E.A.; Fialho, J.D.F.; Faleiro, F.G.; Bellon, G.; Fonseca, K.G.D.; Carvalho, L.J.C.B.; Silva, M.S.; Paula-Moraes, S.V.D.; Filho, M.O.S.D.S.; Silva, K.N.D. Divergência genética entre acessos açucarados e não açucarados de mandioca. Pesqui. Agropecaria Bras. 2008, 43, 1707–1715. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, E.J.D.; Ferreira, C.F.; Santos, V.D.S.; Jesus, O.N.D.; Oliveira, G.A.F.; Silva, M.S.D. Potential of SNP markers for the characterization of brazilian cassava germplasm. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2014, 127, 1423–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aristizábal, J.; Sánchez, T.; Lorío, D.M. Guía Técnica Para Producción y Análisis de Almidón de Yuca; FAO: Roma, Italy, 2007; Volume 163, pp. 2–3. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J.T.D.; Paula, C.D.D.; Oliveira, T.M.D.; Pérez, O.A. Cassava derivatives and toxic components in Brazil. Temas Agrar. 2008, 13, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, W.M.; Dufour, D.L. Why “bitter” cassava? Productivity of “bitter” and “sweet” cassava in a Tukanoan indian settlement in the northwest Amazon. Econ. Bot. 2002, 56, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiwona-Karltun, L.; Mkumbira, J.; Saka, J.; Bovin, M.; Mahungu, N.M.; Rosling, H. The importance of being bitter: A qualitative study on cassava cultivar preference in Malawi. Ecol. Food Nutr. 1998, 37, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresco, L.O. Cassava in shifting cultivation. In A Systems Approach to Agricultural Technology Development in Africa; Royal Tropical Institute: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Mühlen, G.S.; Alves-Pereira, A.; Clement, C.R.; Valle, T.L. Genetic diversity and differentiation of brazilian bitter and sweet manioc varieties (Manihot esculenta Crantz, Euphorbiaceae) based on SSR molecular markers. Tipití J. Soc. Anthropol. Lowl. S. Am. 2013, 11, 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo-Kalin, M. The Amazonia formative: Crop domestication and anthropogenic soils. Diversity 2010, 2, 473–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coomes, O.T. Of stakes, stems, and cuttings: The importance of local seed sustems in traditional Amazonian societies. Prof. Geogr. 2010, 62, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delêtre, M.; McKey, D.B.; Hodkinson, T.R. Marriage exchanges, seed exchanges, and the dynamics of manioc diversity. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 18249–18254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pautasso, M.; Aistaka, G.; Barnaud, A.; Caillon, S.; Clouvel, P.; Coomes, O.T.; Delêtre, M.; Demeulenaere, E.; Santis, P.D.; Döring, T.; et al. Seed exchenge networks for agrobiodiversity conservation. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 33, 151–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samberg, L.H.; Shennan, C.; Zavaleta, E. Farmer seed exchange and crop diversity in a changing agricultural landscape in the southern highlands of Ethiopia. Hum. Ecol. 2013, 41, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, G.A.; González, C.; Lopera, D.C. Informal “seed” systems and the management of gene flow in traditional agroecosystems: The case of cassava in Cauca, Colombia. PLoS One 2011, 6, e29067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, W.M.; Dufour, D.L. Ethnobotanical evidence for cultivar selection among the Tukanoans: Manioc (Manihot esculenta Crantz) in the northwest Amazaon. Cult. Agric. 2006, 28, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, E. Palavra de coca e de tabaco como “conhecimento tradicional”: Cultura, política e desenvolvimento entre os uitoto-murui do rio caraparaná (co). MANA 2011, 17, 69–98. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, J.A.; Clement, C.R. Dark earths and manioc cultivation in central amazonia: A window on pre-colombian agricultural systems? Bol. Mus. Para. Emílio Goeldi 2008, 3, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastik, R.; Geitner, C.; Neuburger, M. Amazonian dark earths in bolivia? A soil study of anthropogenic ring ditches near baures (eastern llanos de mojos). Erdkunde 2013, 67, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-Kalin, M. Slash-burn-and-churn: Landscape history and crop cultivation in pre-columbian amazonia. Quat. Int. 2012, 249, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, L.E. Pueblos Indígenas de la Amazonia e Indicadores de Bienestar Humano en la Encrucijada de la Globalización: Estudio de Caso Amazonia Colombiana; Universidad del País Basco: Bilbao, Spain, 2013. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Acosta, L.E.; Zoria, J. Ticuna traditional knowledge on chagra agriculture and innovative mechanisms for its protection. Bol. Mus. Para. Emílio Goeldi 2012, 7, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steward, A. Nobody farms here anymore: Livelihood diversification in the Amazonian community of carvão, a historical perspective. Agric. Hum. Values 2007, 24, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, L.E.; Zoria, J. Experiencias locales en la protección de los conocimientos tradicionales indígenas en la Amazonia Colombiana. Rev. Colomb. Amazón. 2009, 2, 117–130. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Kawuki, R.S.; Ferguson, M.; Labuschagne, M.; Herselman, L.; Kim, D.-J. Identification, characterisation and application of single nucleotide polymorphisms for diversity assessment in cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz). Mol. Breed. 2009, 23, 669–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciarmiello, L.F.; Piccirillo, P.; Pontecorvo, G.; Luca, A.D.; Kafantaris, I.; Woodrow, P. A PCR based SNPs marker for specific characterization of English walnut (Juglans regia L.) cultivars. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2011, 38, 1237–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.-H.; Li, W.; Zhang, C.; Yang, L.; Chang, R.-Z.; Gaut, B.S.; Qiu, L.-J. Genetic diversity in domesticated soybean (Glycine max) and its wild progenitor (Glycine soja) for simple sequence repeat and single-nucleotide polymorphism loci. New Phytol. 2010, 188, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulloo, M.E.; Hunter, D.; Borelli, T. Ex situ and in situ conservation of agricultural biodiversity: Major advances and research needs. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2010, 38, 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP; ACTO. Environment Outlook in Amazonia Geoamazonia; The United Nations Environment Programme UNEP, The Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization ACTO, The Research Center of the Universidad del Pacífico CIUP: Panama City, Panama, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- IGAC. La Amazonia Colombiana y sus Recursos Proyecto Radargramético del Amazonas Proradam; IGAC: Bogotá, Colombia, 1979. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Duivenvoorden, J.F.; Lips, J.M. Landscape Ecology of the Middle Caquetá Basin; Tropenbos Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 1993; Volume IIIA. [Google Scholar]

- Shorr, N. Early utilization of flood-recession soils as a response to the intensification of fishing and upland agriculture: Resource-use dynamics in a large Tikuna community. Hum. Ecol. 2000, 28, 73–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.; Murrieta, R.S.S.; Sanches, R.A. Agricultura e alimentação em populações ribeirinhas das várzeas do Amazonas: Novas perspectivas. Ambiente Soc. 2005, 8, 1–22. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Eden, M.J.; Andrade, A. Ecological aspects of swidden cultivation among the Andoke and Witoto Indians of the Colombian Amazon. Hum. Ecol. 1987, 15, 339–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA. Soil Taxonomy a Basic System of Soil Classification for Making and Interpreting Soil Surveys; USDA United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1999; Volume 436.

- Piedade, M.T.F.; Worbes, M.; Junk, W.J. Geological controls on elemental fluxes in communities of higher plants in amazonian floodplains. In The Biochemistry of the Amazon Basin; McClain, M.E., Victoria, R.L., Richey, J.E., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 225–227. [Google Scholar]

- Denevan, W.M. A bluff model of riverine settlement in prehistoric Amazonia. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1996, 86, 654–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.; Birk, J.J. State of the scientific knowledge on properties and genesis of anthropogenic dark earths in central Amazonia (terra preta de índio). Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2012, 82, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.; Haumaier, L.; Guggenberger, G.; Zech, W. The “terra preta” phenomenon: A model for sustainable agriculture in the humid tropics. Naturwissenschaften 2001, 88, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, H.N.; Schaefer, C.E.R.; Mello, J.W.V.; Gilkes, R.J.; Ker, J.O.C. Pedogenesis and pre-colombian land use of “terra preta anthrosols” (“Indian Black Earth”) of western Amazonia. Geoderma 2002, 110, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B. Prehistorically modified soils of central Amazonia: A model for sustainable agriculture in the twenty-first century. Philos. Transcr. R. Soc. B 2007, 362, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, L.E.; Mendoza, D. El conocimiento tradicional: Clave en la Construcción del Desarrollo sostenible en la Amazonia Colombiana. Available online: http://nuevo.portalces.org/sites/default/files/6_conocimiento_tradicional_clave_en_la_contruccin_del_desarrollo_sostenible_en_la_amazonia_colombiana.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2014).

- Colombia, R.O. Ley 99 de 1993; Colombia, M.O.E.O., Ed.; Republic of Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 1993. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, E.J.U.D.L. Los indios ticuna del alto Amazonas ante los procesos actuales de cambio cultural y globalización. Rev. Esp. Antropol. Am. 2000, 30, 291–336. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Riaño, E. Los asentamientos ticuna de hoy en la rivera del río Amazonas colombiano. Perspect. Geogr. 2002, 7, 1–38. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, A. Investigación Antropológica de los Antrosoles de Araracuara; Fundación de Investigaciones Arqueologicas Nacionales: Bogotá, Colombia, 1986. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- CIAT. Morphology of the Cassava Plant: Study Guide; CIAT: Cali, Colombia, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Fukoda, W.M.G.; Guevara, C.L. Descritores Morfológicos e Agronômicos para la Caracterizaҫão de Mandioca; EMBRAPA/CNPMF: Cruz das almas, BA, Brazil, 1998; Volume 78. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible. Decreto por el cual se reglamenta el permiso de recolección de especímenes de especies silvestres de la diversidad bilológica con fines de investigación científica no comercial. In Decreto 1376 de 2013; Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible, Ed.; Imprenta Ministerio de Medio Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible: Bogotá, Colombia, 2013; p. 12. Available online: http://wsp.presidencia.gov.co/Normativa/Decretos/2013/Documents/JUNIO/27/DECRETO%201376%20DEL%2027%20DE%20JUNIO%20DE%202013.pdf. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Duitama, J.; Perea, C.S.; Ovalle, T.; Aranzales, E.; Ballen, C.; Calle, F.; Dufour, D.; Parsa, S.; Alzate, A.; Debouck, D.; et al. Revisiting cassava genetic diversity reveals eco-geographic signature of the crop’s domestication. Nat. Genet. 2014. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Deng, T.; Chu, X.; Yang, R.; Jiang, J.; Shen, G.; Yu, R. Rolling circle amplification combined with gold nanoparticle aggregates for highly sensitive identification of single-nucleotide polymorphisms. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 2811–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spurgeon, S.L.; Jones, R.C.; Ramakrishnan, R. High throughput gene expression measurement with real time PCR in a microfluidic dynamic array. PLoS One 2008, 3, e1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawuki, R.S.; Herselman, L.; Labuschagne, M.T.; Nzuki, I.; Ralimanana, I.; Bidiaka, M.; Kanyange, M.C.; Gashaka, G.; Masumba, E.; Mkamilo, G.; et al. Genetic diversity of cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) landraces and cultivars from southern, eastern and central Africa. Plant Genet. Resour. Charact. Util. 2013, 11, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, J.K.; Stephens, M.; Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 2000, 155, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Evanno, G.; Regnaut, S.; Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software structure: A simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 2005, 14, 2611–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nei, M. Analysis of gene diversity in subdivided populations. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 1973, 70, 3321–3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shete, S.; Tiwari, H.; Elston, R.C. On estimating the heterozygosity and polymorphism information content value. Theor. Popul. Biol. 2000, 57, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peña-Venegas, C.P.; Stomph, T.J.; Verschoor, G.; Lopez-Lavalle, L.A.B.; Struik, P.C. Differences in Manioc Diversity Among Five Ethnic Groups of the Colombian Amazon. Diversity 2014, 6, 792-826. https://doi.org/10.3390/d6040792

Peña-Venegas CP, Stomph TJ, Verschoor G, Lopez-Lavalle LAB, Struik PC. Differences in Manioc Diversity Among Five Ethnic Groups of the Colombian Amazon. Diversity. 2014; 6(4):792-826. https://doi.org/10.3390/d6040792

Chicago/Turabian StylePeña-Venegas, Clara P., Tjeerd Jan Stomph, Gerard Verschoor, Luis A. Becerra Lopez-Lavalle, and Paul C. Struik. 2014. "Differences in Manioc Diversity Among Five Ethnic Groups of the Colombian Amazon" Diversity 6, no. 4: 792-826. https://doi.org/10.3390/d6040792

APA StylePeña-Venegas, C. P., Stomph, T. J., Verschoor, G., Lopez-Lavalle, L. A. B., & Struik, P. C. (2014). Differences in Manioc Diversity Among Five Ethnic Groups of the Colombian Amazon. Diversity, 6(4), 792-826. https://doi.org/10.3390/d6040792