Genome Sequence of Dickeya solani, a New soft Rot Pathogen of Potato, Suggests its Emergence May Be Related to a Novel Combination of Non-Ribosomal Peptide/Polyketide Synthetase Clusters

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

Genome Sequencing and Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sequence Comparisons of D. solani to Other Dickeya Strains

3.2. Manual Identification of Known Virulence Determinants

| D. solani D s0432-1 | D. dadantii 3937 | D. zeae Ech586 | D. paradisiaca Ech703 | D. chrysanthemi Ech1591 | P. atrosepticum SCRI1043 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D. solani D s0432-1 | --- | 94 | 85 | 79 | 86 | 75 |

| D. dadantii 3937 | 94 | --- | 85 | 79 | 87 | 75 |

| D. zeae Ech586 | 85 | 85 | --- | 78 | 86 | 74 |

| D. paradisiaca Ech703 | 79 | 79 | 78 | --- | 79 | 74 |

| D. chrysanthemi Ech1591 | 86 | 87 | 86 | 79 | --- | 75 |

| P. atrosepticum SCRI1043 | 75 | 75 | 74 | 74 | 75 | --- |

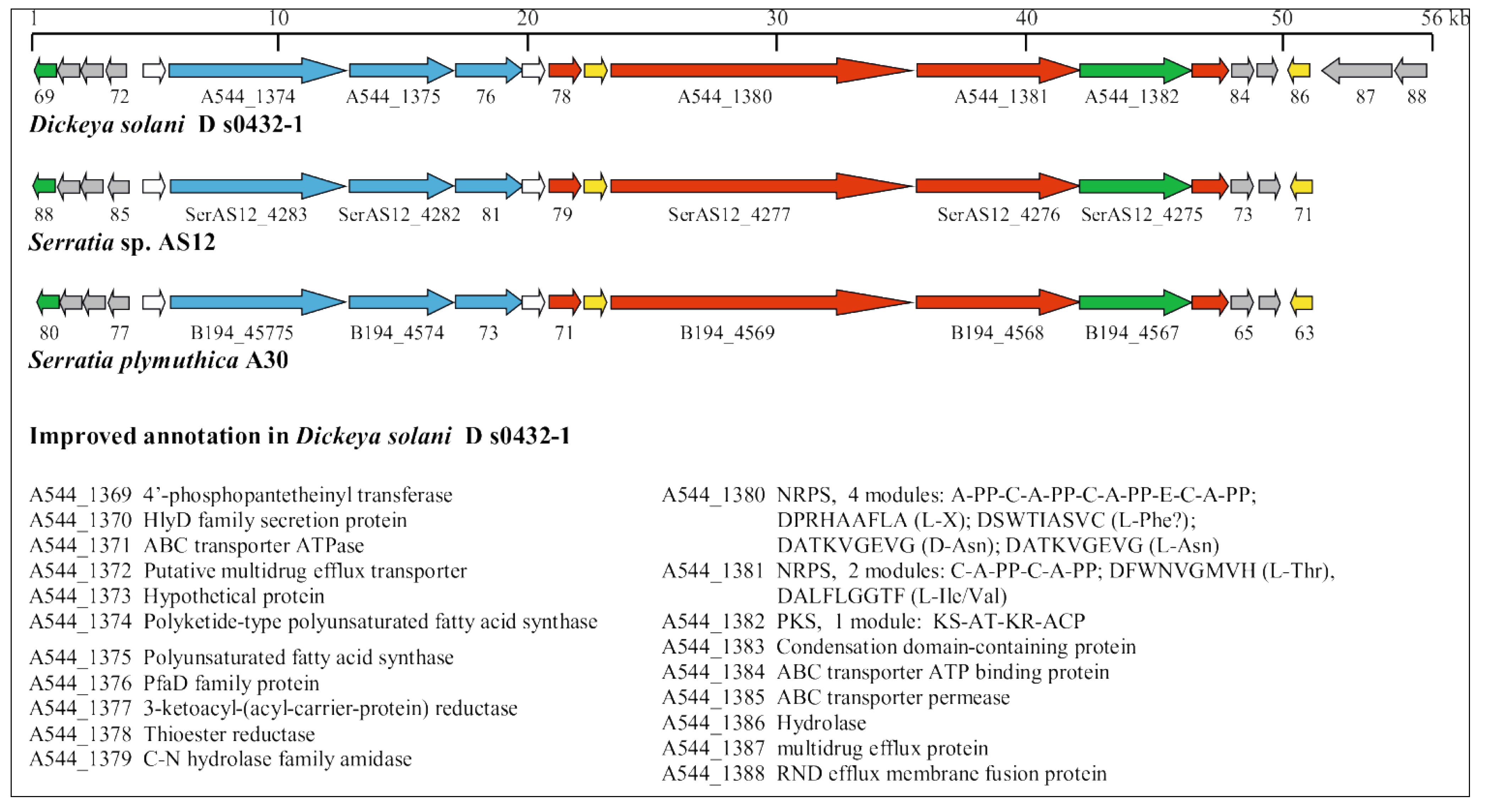

3.3. Identification of Large Genomic Regions in the D. solani Genome, Likely Acquired by Lateral Transmission

3.4. Identification of D. solani s0432-1-Specific ORFs

3.5. Identification of Horizontally Acquired Genomic Islands in D. solani

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- Burkholder, W.; McFadden, L.; Dimock, A. A Bacterial Blight of Chrysanthemums. Phytopathology 1953, 43, 522–526. [Google Scholar]

- Samson, R.; Legendre, J.; Christen, R.; Fischer-Le Saux, M.; Achouak, W.; Gardan, L. Transfer of Pectobacterium chrysanthemi (Burkholder et al. 1953) Brenner et al. 1973 and Brenneria paradisiaca to the Genus Dickeya Gen. Nov as Dickeya chrysanthemi Comb. Nov and Dickeya paradisiaca Comb. Nov and Delineation of Four Novel Species, Dickeya dadantii sp Nov., Dickeya dianthicola Sp Nov., Dickeya dieffenbachiae Sp Nov and Dickeya zeae Sp Nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 1415–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Hibbing, M.E.; Kim, H.; Reedy, R.M.; Yedidia, I.; Breuer, J.; Breuer, J.; Glasner, J.D.; Perna, N.T.; Kelman, A.; et al. Host Range and Molecular Phylogenies of the Soft Rot Enterobacterial Genera Pectobacterium and Dickeya. Phytopathology 2007, 97, 1150–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perombelon, M. Potato Diseases Caused by Soft Rot Erwinias: An Overview of Pathogenesis. Plant Pathol. 2002, 51, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurila, J.; Ahola, V.; Lehtinen, A.; Joutsjoki, T.; Hannukkala, A.; Rahkonen, A.; Pirhonen, M. Characterization of Dickeya Strains Isolated from Potato and River Water Samples in Finland. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2008, 122, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slawiak, M.; van Beckhoven, J.R.C.M.; Speksnijder, A.G.C.L.; Czajkowski, R.; Grabe, G.; van der Wolf, J.M. Biochemical and Genetical Analysis Reveal a New Clade of Biovar 3 Dickeya Spp. Strains Isolated from Potato in Europe. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2009, 125, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsror (Lahkim), L.; Erlich, O.; Lebiush, S.; Hazanovsky, M.; Zig, U.; Slawiak, M.; Grabe, G.; van der Wolf, J.M.; van de Haar, J.J. Assessment of Recent Outbreaks of Dickeya Sp (Syn. Erwinia chrysanthemi) Slow Wilt in Potato Crops in Israel. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2009, 123, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsror (Lahkim), L.; Erlich, O.; Lebiush, S.; van der Wolf, J.; Czajkowski, R.; Mozes, G.; Sikharulidze, Z.; Ben Daniel, B. First Report of Potato Blackleg Caused by a Biovar 3 Dickeya Sp. in Georgia. New Disease Reports 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Wolf, J.M.; Nijhuis, E.H.; Kowalewska, M.J.; Saddler, G.S.; Parkinson, N.; Elphinstone, J.G.; Pritchard, L.; Toth, I.K.; Lojkowska, E.; Potrykus, M.; et al. Dickeya solani Sp. Nov., a Pectinolytic Plant Pathogenic Bacterium Isolated from Potato (Solanum tuberosum). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, I.K.; van der Wolf, J.M.; Saddler, G.; Lojkowska, E.; Helias, V.; Pirhonen, M.; Tsror, L.; Elphinstone, J.G. Dickeya Species: An Emerging Problem for Potato Production in Europe. Plant Pathol. 2011, 60, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czajkowski, R.; de Boer, W.J.; Velvis, H.; van der Wolf, J.M. Systemic Colonization of Potato Plants by a Soilborne, Green Fluorescent Protein-Tagged Strain of Dickeya Sp Biovar 3. Phytopathology 2010, 100, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czajkowski, R.; de Boer, W.J.; van der Zouwen, P.S.; Kastelein, P.; Jafra, S.; de Haan, E.G.; van den Bovenkamp, G.W.; van der Wolf, J.M. Virulence of ‘Dickeya solani’ and Dickeya dianthicola Biovar-1 and -7 Strains on Potato (Solanum tuberosum). Plant Pathol. 2012, 62, 597–610. [Google Scholar]

- Nykyri, J.; Niemi, O.; Koskinen, P.; Nokso-Koivisto, J.; Pasanen, M.; Broberg, M.; Plyusnin, I.; Törönen, P.; Holm, L.; Pirhonen, M.; et al. Revised Phylogeny and Novel Horizontally Acquired Virulence Determinants of the Model Soft Rot Phytopathogen Pectobacterium wasabiae SCC3193. PLoS Pathogens 2012, 8, e1003013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margulies, M.; Egholm, M.; Altman, W.; Attiya, S.; Bader, J.; Bemben, L.; Berka, J.; Braverman, M.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Z.; et al. Genome Sequencing in Microfabricated High-Density Picolitre Reactors. Nature 2005, 437, 376–380. [Google Scholar]

- Staden, R.; Beal, K.F.; Bonfield, J.K. The Staden Package, 1998. Methods Mol. Bio. 2000, 132, 115. [Google Scholar]

- Hyatt, D.; Chen, G.; LoCascio, P.F.; Land, M.L.; Larimer, F.W.; Hauser, L.J. Prodigal: Prokaryotic Gene Recognition and Translation Initiation Site Identification. BMC Bioinformatics 2010, 11, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pati, A.; Ivanova, N.N.; Mikhailova, N.; Ovchinnikova, G.; Hooper, S.D.; Lykidis, A.; Kyrpides, N.C. GenePRIMP: A Gene Prediction Improvement Pipeline for Prokaryotic Genomes. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radivojac, P.; Clark, W.T.; Oron, T.R.; Schnoes, A.M.; Wittkop, T.; Sokolov, A.; Graim, K.; Funk, C.; Verspoor, K.; Ben-Hur, A.; et al. A Large-Scale Evaluation of Computational Protein Function Prediction. Nat. Methods 2013, 10 (suppl.), 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatusov, R.; Galperin, M.; Natale, D.; Koonin, E. The COG Database: A Tool for Genome-Scale Analysis of Protein Functions and Evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagesen, K.; Hallin, P.; Rodland, E.A.; Staerfeldt, H.; Rognes, T.; Ussery, D.W. RNAmmer: Consistent and Rapid Annotation of Ribosomal RNA Genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 3100–3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, M.; Rossello-Mora, R. Shifting the Genomic Gold Standard for the Prokaryotic Species Definition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009, 106, 19126–19131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, A.E.; Mau, B.; Perna, N.T. ProgressiveMauve: Multiple Genome Alignment with Gene Gain, Loss and Rearrangement. PLoS One 2010, 5, e11147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, L.; Humphris, S.; Saddler, G.S.; Parkinson, N.M.; Bertrand, V.; Elphinstone, J.G.; Toth, I.K. Detection of Phytopathogens of the Genus Dickeya using a PCR Primer Prediction Pipeline for Draft Bacterial Genome Sequences. Plant Pathol. 2013, 62, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BLAST. Available online: http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast.cgi (accessed on 8 March 2013).

- InterProScan 4. Available online: http://www.ebi.ac.uk/tools/pfa/iprscan/ (accessed on 8 March 2013).

- Stachelhaus, T.; Mootz, H.; Marahiel, M. The Specificity-Conferring Code of Adenylation Domains in Nonribosomal Peptide Synthetases. Chem. Biol. 1999, 6, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PKS/NRPS Analysis Web-site. Available online: http://nrps.igs.umaryland.edu/nrps (accessed on 8 March 2013).

- Bachmann, B.O.; Ravel, J. in Silico Prediction of Microbial Secondary Metabolic Pathways from DNA Sequence Data. Methods Enzymol. 2009, 458, 181–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrindt, U.; Hochhut, B.; Hentschel, U.; Hacker, J. Genomic Islands in Pathogenic and Environmental Microorganisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004, 2, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Mendoza, D.; Coulthurst, S.J.; Humphris, S.; Campbell, E.; Welch, M.; Toth, I.K.; Salmond, G.P.C. A Multi-Repeat Adhesin of the Phytopathogen, Pectobacterium atrosepticum, is Secreted by a Type I Pathway and is Subject to Complex Regulation Involving a Non-Canonical Diguanylate Cyclase. Mol. Microbiol. 2011, 82, 719–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, S.K.; Diner, E.J.; de Roodenbeke, C.T.K.; Burgess, B.R.; Poole, S.J.; Braaten, B.A.; Jones, A.M.; Webb, J.S.; Hayes, C.S.; Cotter, P.A.; et al. A Widespread Family of Polymorphic Contact-Dependent Toxin Delivery Systems in Bacteria. Nature 2010, 468, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blot, N.; Berrier, C.; Hugouvieux-Cotte-Pattat, N.; Ghazi, A.; Condemine, G. The Oligogalacturonate-Specific Porin KdgM of Erwinia chrysanthemi belongs to a New Porin Family. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 7936–7944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aymeric, J.; Guiseppi, A.; Pascal, M.; Chippaux, M. Mapping and Regulation of the Cel Genes in Erwinia chrysanthemi. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1988, 211, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yamazaki, A.; Zou, L.; Biddle, E.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, Y.; Lin, H.; Wang, Q.; Yang, C. ClpXP Protease Regulates the Type III Secretion System of Dickeya dadantii 3937 and is Essential for the Bacterial Virulence. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2010, 23, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandersman, C.; Delepelaire, P.; Letoffe, S. Secretion Processing and Activation of Erwinia chrysanthemi Proteases. Biochimie 1990, 72, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattinen, L.; Tshuikina, M.; Mae, A.; Pirhonen, M. Identification and Characterization of Nip, Necrosis-Inducing Virulence Protein of Erwinia carotovora Subsp carotovora. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2004, 17, 1366–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottmann, C.; Luberacki, B.; Kuefner, I.; Koch, W.; Brunner, F.; Weyand, M.; Mattinen, L.; Pirhonen, M.; Anderluh, G.; Seitz, H.U.; et al. A Common Toxin Fold Mediates Microbial Attack and Plant Defense. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 10359–10364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi-Pour, N.; Condemine, G.; Hugouvieux-Cotte-Pattat, N. The Secretome of the Plant Pathogenic Bacterium Erwinia chrysanthemi. Proteomics 2004, 4, 3177–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expert, D. Withholding and Exchanging Iron: Interactions between Erwinia spp. and their Plant Hosts. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1999, 37, 307–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boughammoura, A.; Matzanke, B.F.; Boettger, L.; Reverchon, S.; Lesuisse, E.; Expert, D.; Franza, T. Differential Role of Ferritins in Iron Metabolism and Virulence of the Plant-Pathogenic Bacterium Erwinia chrysanthemi 3937. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 1518–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boughammoura, A.; Expert, D.; Franza, T. Role of the Dickeya dadantii Dps Protein. Biometals 2012, 25, 423–433. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchart, F.; Delangle, A.; Lemoine, J.; Bohin, J.; Lacroix, J. Proteomic Analysis of a Non-Virulent Mutant of the Phytopathogenic Bacterium Erwinia chrysanthemi Deficient in Osmoregulated Periplasmic Glucans: Change in Protein Expression is Not Restricted to the Envelope, but Affects General Metabolism. Microbiology-(UK) 2007, 153, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Solanilla, E.; Garcia-Olmedo, F.; Rodriguez-Palenzuela, P. Inactivation of the sapA to sapF Locus of Erwinia chrysanthemi Reveals Common Features in Plant and Animal Bacterial Pathogenesis. Plant Cell 1998, 10, 917–924. [Google Scholar]

- Costechareyre, D.; Balmand, S.; Condemine, G.; Rahbe, Y. Dickeya dadantii, a Plant Pathogenic Bacterium Producing Cyt-Like Entomotoxins, Causes Septicemia in the Pea Aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum. PLoS One 2012, 7, e30702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charkowski, A.; Blanco, C.; Condemine, G.; Expert, D.; Franza, T.; Hayes, C.; Hugouvieux-Cotte-Pattat, N.; Lopez Solanilla, E.; Low, D.; Moleleki, L.; et al. The Role of Secretion Systems and Small Molecules in Soft-Rot Enterobacteriaceae Pathogenicity. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2012, 50, 425–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattinen, L.; Somervuo, P.; Nykyri, J.; Nissinen, R.; Kouvonen, P.; Corthals, G.; Auvinen, P.; Aittamaa, M.; Valkonen, J.P.T.; Pirhonen, M. Microarray Profiling of Host-Extract-Induced Genes and Characterization of the Type VI Secretion Cluster in the Potato Pathogen Pectobacterium atrosepticum. Microbiology-(UK) 2008, 154, 2387–2396. [Google Scholar]

- Nasser, W.; Dorel, C.; Wawrzyniak, J.; Van Gijsegem, F.; Groleau, M.; Déziel, E.; Reverchon, S. Vfm a New Quorum Sensing System Controls the Virulence of Dickeya dadantii. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 15, 865–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, K.; Nasser, W.; Tsuyumu, S. Self-Regulation of Pir, a Regulatory Protein Responsible for Hyperinduction of Pectate Lyase in Erwinia chrysanthemi EC16. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 1999, 12, 385–390. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.C.; Madupu, R.; Durkin, A.S.; Ekborg, N.A.; Pedamallu, C.S.; Hostetler, J.B.; Radune, D.; Toms, B.S.; Henrissat, B.; Coutinho, P.M; et al. The Complete Genome of Teredinibacter turnerae T7901: An Intracellular Endosymbiont of Marine Wood-Boring Bivalves (Shipworms). PLoS One 2009, 4, e6085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donadio, S.; Monciardini, P.; Sosio, M. Polyketide Synthases and Nonribosomal Peptide Synthetases: The Emerging View from Bacterial Genomics. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2007, 24, 1073–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Du, L.; Sanchez, C.; Edwards, D.J.; Chen, M.; Murrell, J.M. The Biosynthetic Gene Cluster for the Anticancer Drug Bleomycin from Streptomyces verticillus ATCC15003 as a Model for Hybrid Peptide-Polyketide Natural Product Biosynthesis. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001, 27, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piel, J. Biosynthesis of Polyketides by Trans-AT Polyketide Synthases. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2010, 27, 996–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, M.; Effmert, U.; Berg, G.; Piechulla, B. Volatiles of Bacterial Antagonists Inhibit Mycelial Growth of the Plant Pathogen Rhizoctonia solani. Arch. Microbiol. 2007, 187, 351–360. [Google Scholar]

- Matilla, M.A.; Stoeckmann, H.; Leeper, F.J.; Salmond, G.P.C. Bacterial Biosynthetic Gene Clusters Encoding the Anti-Cancer Haterumalide Class of Molecules: Biogenesis of the Broad Spectrum Antifungal and Anti-Oomycete Compound, Oocydin A. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 39125–39138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, S.; Finlay, R.D.; Alstrom, S.; Goodwin, L.; Kyrpides, N.C.; Lucas, S.; Lapidus, A.; Bruce, D.; Pitluck, S.; Peters, L.; et al. Complete Genome Sequence of Serratia plymuthica Strain AS12. Stand. Genomic Sci. 2012, 6, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, H.; Xu, J.; Cox, R.J.; Simpson, T.J.; Zhang, L. C-13 Labeling Reveals Multiple Amination Reactions in the Biosynthesis of a Novel Polyketide Polyamine Antibiotic Zeamine from Dickeya zeae. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 333–335. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, H.; Wu, J.; Liu, Q.; Xi, P.; Lee, J.; Liao, J.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, L. A Novel Multidomain Polyketide Synthase is Essential for Zeamine Production and the Virulence of Dickeya zeae. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2011, 24, 1156–1164. [Google Scholar]

- Masschelein, J.; Mattheus, W.; Gao, L.; Moons, P.; van Houdt, R.; Uytterhoeven, B.; Lamberigts, C.; Lescrinier, E.; Rozenski, J.; Herdewijn, P.; et al. A PKS/NRPS/FAS Hybrid Gene Cluster from Serratia plymuthica RVH1 Encoding the Biosynthesis of Three Broad Spectrum, Zeamine-Related Antibiotics. PLoS One 2013, 8, e54143. [Google Scholar]

- Du, L.H.; Sanchez, C.; Shen, B. Hybrid Peptide-Polyketide Natural Products: Biosynthesis and Prospects Toward Engineering Novel Molecules. Metab. Eng. 2001, 3, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaisser, S.; Hughes, C. A Locus Coding for Putative Non Ribosomal peptide/polyketide Synthase Functions is Mutated in a Swarming-Defective Proteus mirabilis Strain. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1997, 253, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikaido, H. Antibiotic Resistance Caused by Gram-Negative Multidrug Efflux Pumps. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1998, 27, S32–S41. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, W.; Nester, E. Characterization of a Putative RND-Type Efflux System in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Gene 2001, 270, 245–252. [Google Scholar]

- Burse, A.; Weingart, H.; Ullrich, M. The Phytoalexin-Inducible Multidrug Efflux Pump AcrAB Contributes to Virulence in the Fire Blight Pathogen, Erwinia amylovora. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2004, 17, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valecillos, A.; Palenzuela, P.; Lopez-Solanilia, E. The Role of several Multidrug Resistance Systems in Erwinia chrysanthemi Pathogenesis. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2006, 19, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, R.M.; Cheng, X. Restriction-Modification Systems. In Modern Microbial Genetics, 2nd ed.; Streips, U.N., Yasbin, R.E., Eds.; Wiley-Liss, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN: 978-0-471-38665-0; p. 178. [Google Scholar]

- Pirhonen, Minna. Personal Communication. University of Helsinki: Helsinki, Finland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Soballe, B.; Poole, R. Microbial Ubiquinones: Multiple Roles in Respiration, Gene Regulation and Oxidative Stress Management. Microbiology-(UK) 1999, 145, 1817–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brondijk, T.; Fiegen, D.; Richardson, D.; Cole, J. Roles of NapF, NapG and NapH, Subunits of the Escherichia coli periplasmic Nitrate Reductase, in Ubiquinol Oxidation. Mol. Microbiol. 2002, 44, 245–255. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, F.; Cheng, G.; Xu, H.; Wang, Z.; Lei, L.; Li, Y. Identification of a Novel Gene for Biosynthesis of a Bacteroid-Specific Electron Carrier Menaquinone. PLoS One 2011, 6, e28995. [Google Scholar]

- Juhas, M.; van der Meer, J.R.; Gaillard, M.; Harding, R.M.; Hood, D.W.; Crook, D.W. Genomic Islands: Tools of Bacterial Horizontal Gene Transfer and Evolution. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 33, 376–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H.; Hensel, M. Pathogenicity Islands in Bacterial Pathogenesis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2004, 17, 14–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Garlant, L.; Koskinen, P.; Rouhiainen, L.; Laine, P.; Paulin, L.; Auvinen, P.; Holm, L.; Pirhonen, M. Genome Sequence of Dickeya solani, a New soft Rot Pathogen of Potato, Suggests its Emergence May Be Related to a Novel Combination of Non-Ribosomal Peptide/Polyketide Synthetase Clusters. Diversity 2013, 5, 824-842. https://doi.org/10.3390/d5040824

Garlant L, Koskinen P, Rouhiainen L, Laine P, Paulin L, Auvinen P, Holm L, Pirhonen M. Genome Sequence of Dickeya solani, a New soft Rot Pathogen of Potato, Suggests its Emergence May Be Related to a Novel Combination of Non-Ribosomal Peptide/Polyketide Synthetase Clusters. Diversity. 2013; 5(4):824-842. https://doi.org/10.3390/d5040824

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarlant, Linda, Patrik Koskinen, Leo Rouhiainen, Pia Laine, Lars Paulin, Petri Auvinen, Liisa Holm, and Minna Pirhonen. 2013. "Genome Sequence of Dickeya solani, a New soft Rot Pathogen of Potato, Suggests its Emergence May Be Related to a Novel Combination of Non-Ribosomal Peptide/Polyketide Synthetase Clusters" Diversity 5, no. 4: 824-842. https://doi.org/10.3390/d5040824

APA StyleGarlant, L., Koskinen, P., Rouhiainen, L., Laine, P., Paulin, L., Auvinen, P., Holm, L., & Pirhonen, M. (2013). Genome Sequence of Dickeya solani, a New soft Rot Pathogen of Potato, Suggests its Emergence May Be Related to a Novel Combination of Non-Ribosomal Peptide/Polyketide Synthetase Clusters. Diversity, 5(4), 824-842. https://doi.org/10.3390/d5040824