1. Introduction

The extreme variation in elevation in Nepal provides a habitat for three species of bear. Sloth bears (

Melursus ursinus) inhabit the southern lowlands (Terai; <1500 m); Asian black bears (

Ursus thibetanus) live in the Middle Hills region up to the tree line (1500–3500 m); and Tibetan brown bears (

Ursus arctos pruinosus) [

1,

2,

3], which represent the most widely distributed ursid in the world [

4], occur in the Northern Mountain region of Nepal [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

The brown bear population reported in the higher Himalayan protected area of Nepal, that is, in the Annapurna Conservation Area (ACA) and Manasalu Conservation Area (MCA), share habitat with other types of prey and predators of the region [

1,

2,

3,

5]. These include blue sheep, or Bharal (

Pseudois nayaur), which is the major wild prey species, and consequently also their predators such as the snow leopard (

Panthera uncia). Additionally, livestock farming is the predominant human activity in the region, and most of the available pastureland is used for livestock grazing [

1,

2,

3,

5,

6,

7,

8]. The coexistence between wildlife and agricultural practices has the potential for conflict. Brown bears are known to predate livestock in the region; it has been estimated that in the ACA 10% of the brown bears’ diet comes from livestock [

3]. Local people do not frequently encounter brown bears, and consequently associate livestock losses with other predators such as the snow leopard. Nonetheless, livestock depredation may lead to retaliatory killings and consequently a negative impact on conservation of the predatory species in the area [

3].

The first aim in this study is to assess the extent of the brown bear habitat in Nepal. The composition of the vegetation is a major factor defining the suitability of habitat for wild herbivore and livestock populations [

5,

8], and yet there is limited information on the vegetation composition of the habitat that the brown bear shares with blue sheep and livestock in the upper Mustang region. An understanding of the resource base shared by these species is important for the preparation of a management plan to ensure the long-term sustainability of the native fauna and minimize conflicts between wildlife and agricultural practices on which the local communities are dependent. The second aim of the present study is to examine habitat use by the brown bear and its overlap with the blue sheep and livestock in relation to the vegetation composition in the upper Mustang region.

The government of Nepal has given legal protection to the brown bear under the National Park and Wildlife Act (NPWA) 1973. Brown bear research and conservation activities were initiated in Nepal in 2004 [

1,

2,

3,

5,

8]. This included a survey for the presence of the brown bear in ACA, and in 2010 Aryal

et al. [

3] confirmed the presence of brown bears in the MCA. Since that time, continued research and conservation has been conducted in the ACA. In January 2010, the first brown bear conservation action plan preparation workshop was organized with the involvement of local people, relevant government agencies, non-government organizations (NGOs), international non-governmental organizations (INGOs), and local and international bear scientists [

9]. Following those activities, a draft brown bear conservation action plan was prepared and discussed at a second national level workshop in March 2011.

The third aim of this paper is to explore the workshop findings and outline the core components of a plan for bear research and conservation in Nepal. The plan highlights the major activities proposed by local people, scientists and the field-based investigation for brown bear conservation in Nepal. It is anticipated that a conservation strategy that focuses on a top predator, the brown bear, will not only help to ensure stable coexistence between this species and its competitors, including livestock, but also produce an umbrella effect for the conservation of other wild species and livestock in the region.

2. Study Area

Nepal (147,181 km

2) is located in South-Asia on the southern slopes of the central-Himalayan Range (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). The average length of Nepal is 885 km, and the width varies from 145 to 241 km. Mountains cover ~86% of the total land area, while the remaining 14% is comprised of the Terai flatlands (60–300 m above sea level). Nepal contains eight of the ten highest mountains in the world, the tallest being Sagarmatha (Mount Everest; 8848 m) [

10].

In addition to Nepal’s legendary Himalayan Range, the country is a hotspot for biodiversity. Species richness in Nepal is a product of its geographic position as well as its diverse altitudinal and climatic gradients. Nepal contains ~4.3 million ha (29%) of forest, 1.6 million ha (10.6%) of scrubland and degraded forest, 1.7 million ha (12%) of grassland, 3.0 million ha (21%) of farmland, and about 1.0 million ha (7%) of uncultivated lands outside Nepal’s protected areas [

10]. Within Nepal there are 10 national parks, three wildlife reserves, one hunting reserve, six conservation areas, and 11 buffer zones covering 34,187 km

2 (23.23%) [

11].

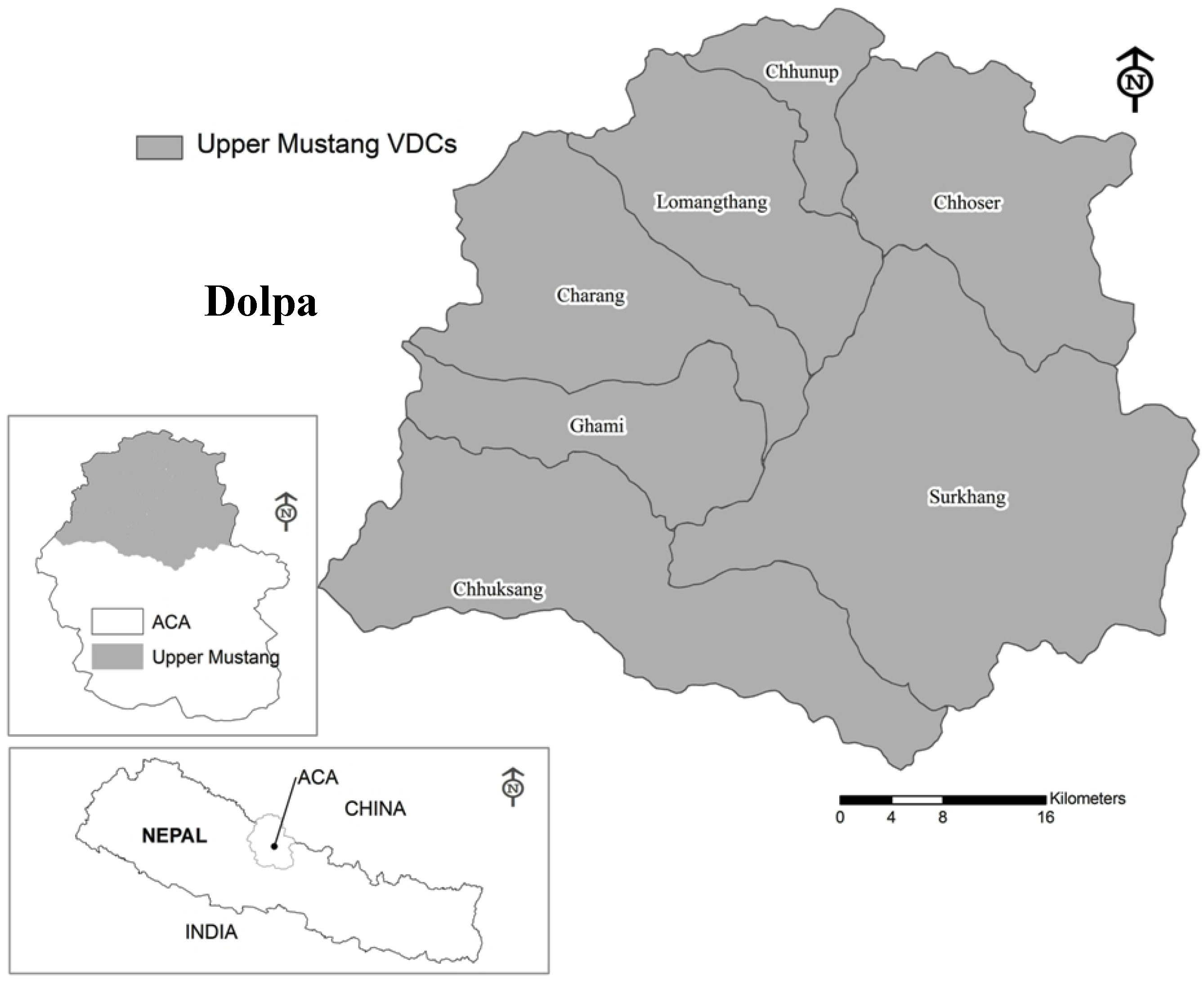

Our field study was conducted in the upper Mustang region of ACA in Nepal (

Figure 1). The northern part of this area borders the Tibetan region of China and has very low annual rainfall (<200 mm). Animal husbandry is the main income source of the local people of the region [

7]. The upper Mustang region consists of seven village development committees (VDCs), with a human population of <15,000 [

10]. We performed a habitat survey during September–October 2010, in the pastureland of the upper Mustang VDCs (Lomangthang, Chhoser, Chhunup, Surkhang) and its border regions in ACA and Dolpa district (

Figure 2). We used brown bear distribution data from the MCA from our earlier study [

3], and these data were also used for modeling the brown bear distribution in the area.

Figure 1.

Location of the study area within Nepal.

Figure 1.

Location of the study area within Nepal.

Figure 2.

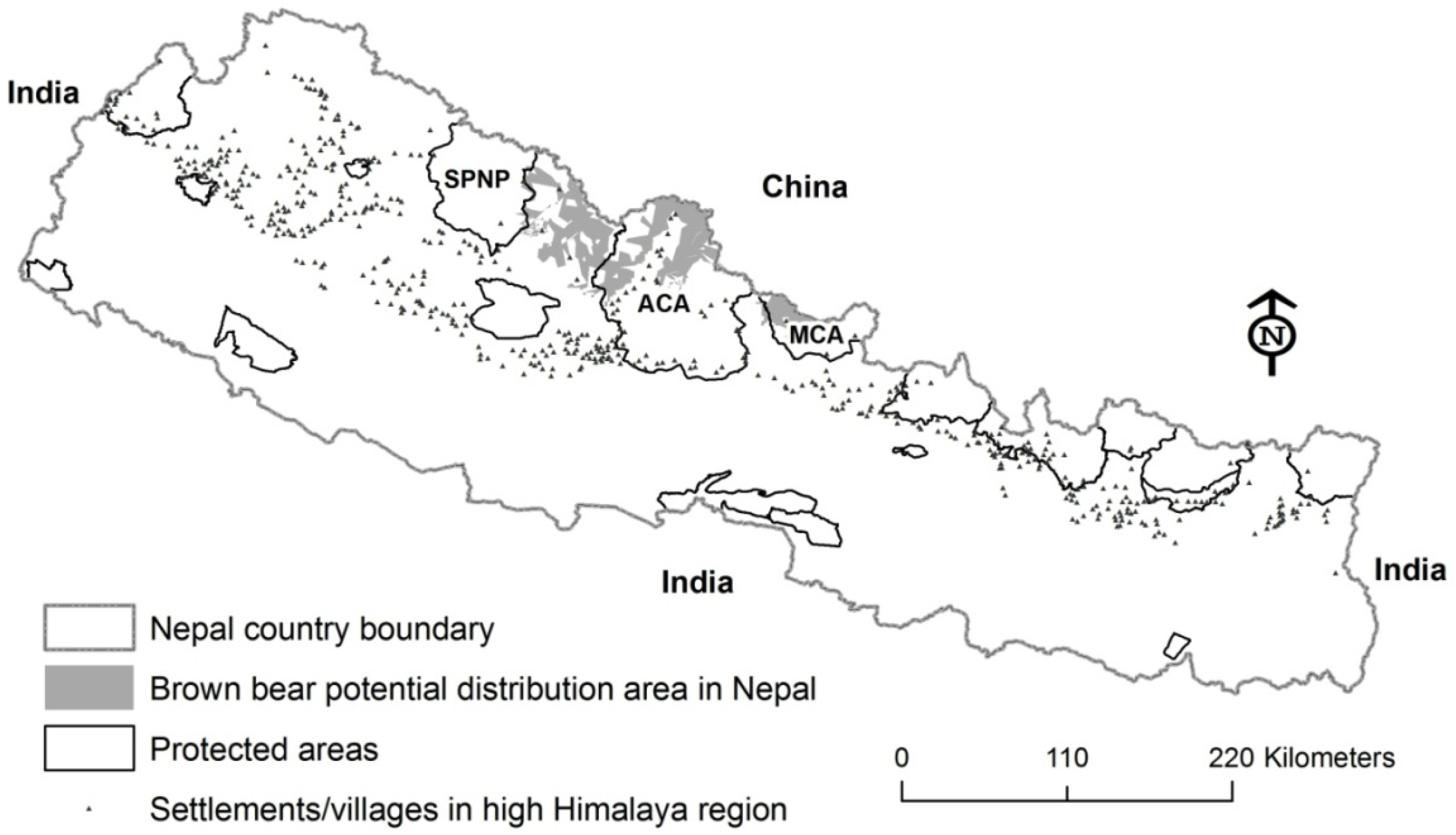

Potential brown bear distribution between the eastern border of Shey Phoksundo National Park (SPNP) and the Manasalu Conservation Area (MCA) predicted by our model.

Figure 2.

Potential brown bear distribution between the eastern border of Shey Phoksundo National Park (SPNP) and the Manasalu Conservation Area (MCA) predicted by our model.

3. Methods

3.1. Potential Brown Bear Habitat in Nepal

We prepared a potential brown bear distribution habitat map using past records of brown bear presence [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5] and information about the habitat based on the present study in ACA and the border regions of ACA and the Dolpa district. To determine the distribution of the potential habitat for brown bears within the ACA, the MCA [

3], and the corridors between the ACA and Shey Phoksundo National Park (SPNP), habitat features were quantified in locations where brown bear presence was directly confirmed. ArcGIS 9.3 (Version 9.3, ESRI Inc., Redlands, CA, USA) software was used to prepare maps and modeling. The features we included in the model were elevation, slope, aspect, and vegetation types. We used habitat layers (elevation, land use-ecology and settlement) that were freely available from

http://geoportal.icimod.org [

12]. A 20 m contour interval layer was used to make a digital elevation model (DEM) of the bear distribution area, and 3D analysis was used to further reclassify the DEM at 500 m elevation intervals. Aspect and slope were also computed from 3D analysis. This was then converted to a shape file for area calculation and analysis.

Additionally, we used information derived from two national level workshops on a conservation action plan for brown bear that were conducted in Nepal. At the workshops, the participants (scientists, conservation officials, field personnel and representatives of local communities) pooled information to generate an understanding of the features of brown bear habitat. On this basis, together with information on direct signs of brown bear (sightings, scats, etc.), maps of brown bear distributions were prepared during the workshop sessions. These were subsequently loaded and geo-referenced in the GIS layers to refine our distribution model of the brown bear in the region.

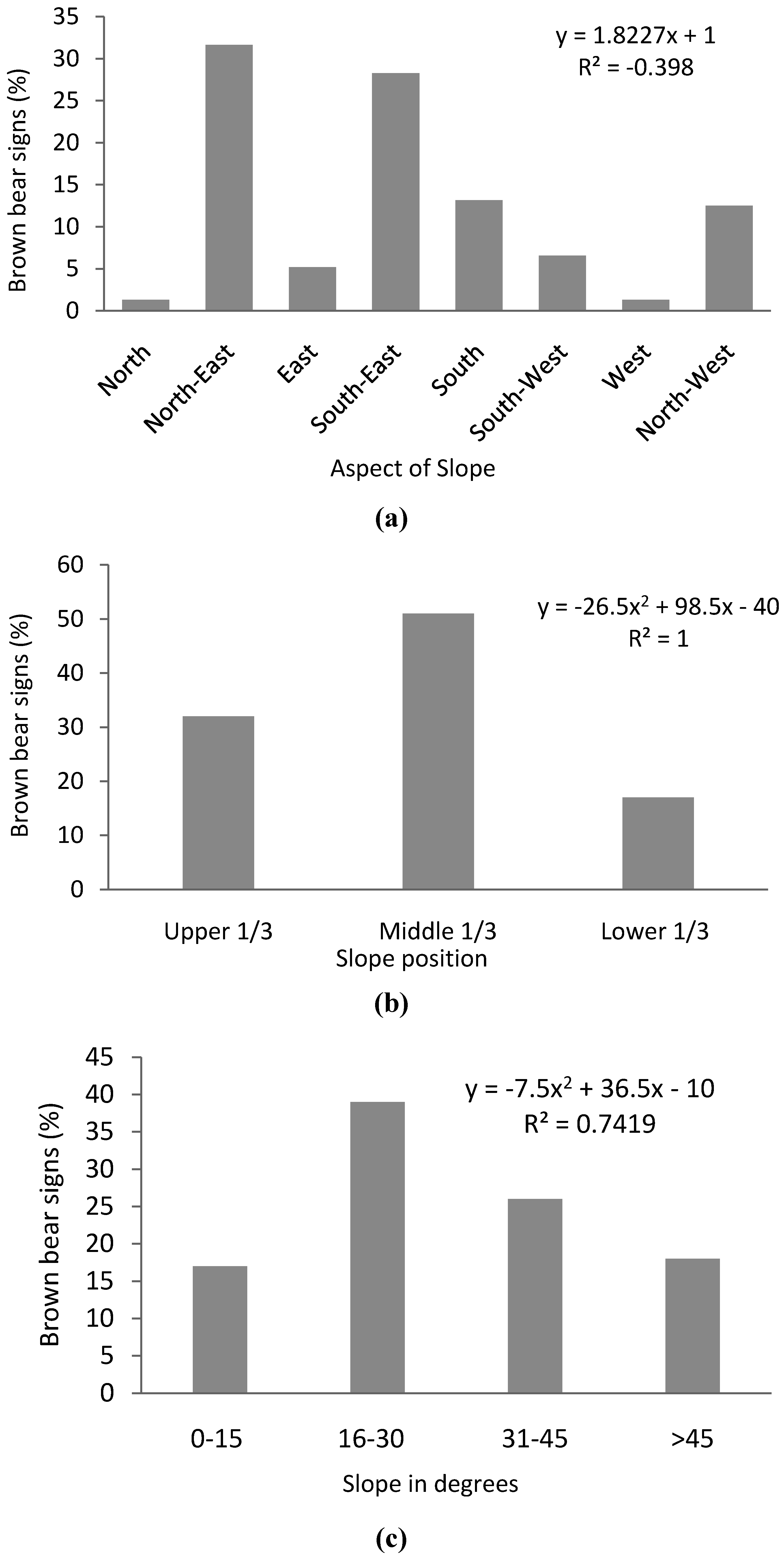

3.2. Brown Bear Habitat Survey

A vegetation survey was conducted in the confirmed brown bear habitat of the upper Mustang region in 2010–2011. Vegetation was sampled using ‘animal use plots’ where bear signs were encountered (digging sites, footprints, hair, scats). Plot sizes were 4 m × 4 m for estimating species composition and coverage of woody shrubs (woody plants <3 m height), and 1 m × 1 m for estimating species composition and coverage of herbs (plants ≤1 m height). Additionally, parameters such as aspect, slope, elevation, vegetation, anthropogenic activities, and the presence of blue sheep and livestock, as well as the presence/absence of uprooted plants for fuel wood were recorded during the survey.

Based on the frequency and abundance of herbs and shrubs, an Importance Value Index (IVI) (Equation (1)) of vegetation for brown bear habitat was calculated [

8]. The IVI ranges from 0 to 300, the highest value of vegetation represents more importance than the lowest value.

where: frequency (F) = number of plots with the individual species × 100/total number of plots; relative frequency (RF) = frequency of any one species × 100/total frequency of all species; density (D) = total number of species in all plots/total number of plots × area of plots; relative density (RD) = density of a species × 100/total density of all species; and relative coverage (RC) = coverage of a species × 100/total coverage.

3.3. Habitat Overlap among Brown Bear, Livestock, and Blue Sheep

The overlap of habitat among brown bears, livestock and blue sheep was determined using methods developed by Real [

13] and Real and Vargas [

14]. Once signs of brown bears (scat, tracks, or dig sites) were encountered, the site was sampled (plots = 90; size 50 m × 50 m) and an additional sample plot (50 m × 50 m) located 200 m in a random direction was used as a matched pair plot. Both the primary and matched pair plots (n = 90) were searched for signs of blue sheep, livestock and brown bear. Habitat overlap between brown bear (A) and blue sheep or livestock (B) was calculated separately using Jaccard’s similarity index (

J) (Equation (2)) [

8,

13,

14] from presence/absence data recorded from these plots. The associated probability for

J was calculated to determine if the value for the index (ranging from 0 to 1) differed from what would be expected at random [

11,

13] as

where C is the number of plots used by both brown bear and blue sheep or livestock. In this case, the probabilities associated with Jaccard’s index depend on the total number of attributes present in either of the two habitats compared (N) (Equation (3)). N was calculated as:

Finally, the percentage of area overlap by blue sheep and livestock with brown bear occurrence was calculated as:

here: nb is the plot area in which blue sheep signs were recorded; TA is the total sample plot area (i.e., including presence and absence); and nl is the plot area with livestock signs.

3.4. Brown Bear Conservation Workshops

Nepal’s first systematic brown bear study was conducted in 2008 [

3], and the first national brown bear conservation participatory action plan workshop was conducted in January 2010 [

9]. The second workshop took place on 9 March 2011 at the Annapurna Conservation Area Project (ACAP) offices, Pokhara, in collaboration with the ACAP, the Department of National Park and Wildlife Conservation (NPWC), Department of Forest and the Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation/Government of Nepal. The main aim of this workshop was to review feedback, comments and suggestions for finalizing the draft brown bear conservation action plan. The workshop was conducted in a participatory way with the active involvement of 63 participants from government, NGOs, local leaders, and the Institute of Forestry, Tribhuvan University, Pokhara. In the workshop the proposed brown bear conservation activities in Nepal were presented and each plan was discussed with the participants and their suggestions for improvements were noted. Additionally, priorities for research into brown bear conservation in Nepal were discussed. We report in the present paper the main outputs and major findings from the discussion and feedback sessions that were included in the emerging brown bear conservation plan.

5. Discussion

Brown bear research in Nepal started after 2004 and confirmed the presence of the brown bear in the ACA, the MCA and in the corridor between SPNP and the ACA [

1,

2,

7]. The present study extends this research, providing an estimate of the potential brown bear habitat and its distribution within the area. Our research found that an area of ~4000 km

2 is predicted to be a suitable habitat for the brown bear, of which approximately 48% falls outside of the protected area. This means that it is excluded from research and conservation activities for not only the brown bear, but also for other mammal species in that region. It is important that presence/absence surveys be conducted in these regions, and effective conservation activities be implemented.

Top priority should be given to brown bear research and conservation in the corridor between the SPNP and the ACA, and these activities should be extended in the western and eastern parts of country. Furthermore, specific conservation and research activities should also be included in each protected area. Habitat modeling in the present study has shown that there is a potential connecting corridor between ACA and SPNP (

Figure 1), but the current threats of climate change, habitat fragmentation, and human disturbance and settlement have created obstacles to the movement of animals through these landscapes. The changing climate appears to result in animal ranges shifting to different elevations and the disappearance of habitat for some species [

15]. Perhaps significantly, local people living in the mid hill regions of Samma village of the Gorkha district have reported the appearance of Asian black bears at elevations higher than they usually occur. Ecological connectivity is a good strategy for reducing the negative effects of climate change on biological diversity [

16,

17] and will help the flow of animals and ecological processes across the landscape [

18]. Maintaining connectivity between protected areas should help brown bear populations to cope with changing climate patterns and help to maintain a viable population of brown bears in Nepal.

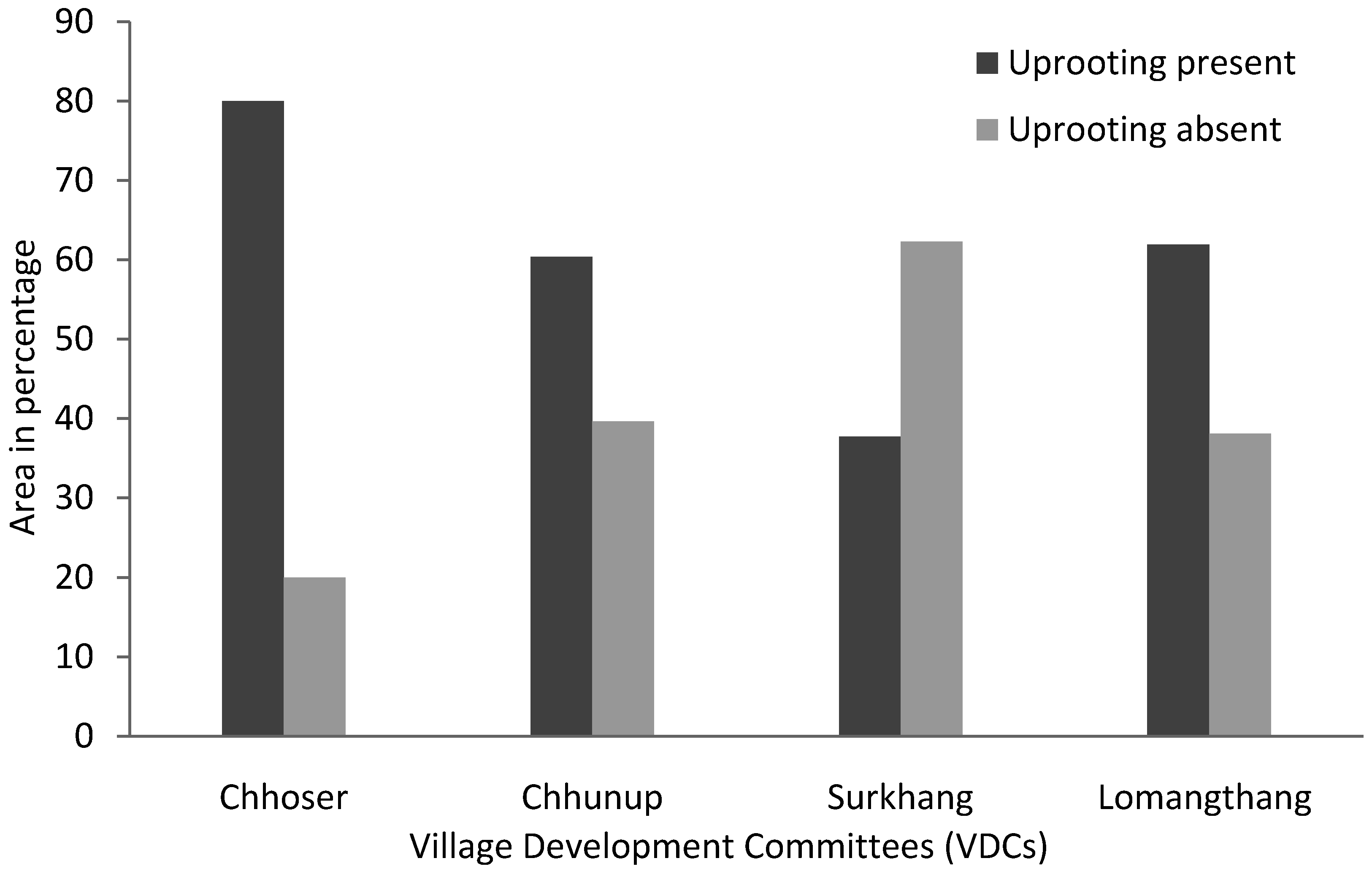

The uprooting of shrubs and the collection of dung are very common practices within the study area due to the absence of trees necessary to meet demands for fuel wood.

Caragana spp,

Androsace sarmentosa,

Lonicera spp, and

Rosa spp continue to be over-harvested for this purpose. In most cases the entire shrub is harvested, and the woody roots are stored on the roofs of houses to dry for winter use (

Figure 6). Such practices also exist in the Himalayan region of India [

19]. There is no alternative fuel wood available, with the exception of a few private plantations in the upper Mustang region. The uncontrolled collection of wild plants for fuel should gradually be banned, and alternative fuel wood sources should be provided for local people. Private fuel wood tree plantations could be promoted, as could the use of solar energy.

Figure 6.

Transportation (a,b) and storage (c,d) of uprooted plants for winter fuel.

Figure 6.

Transportation (a,b) and storage (c,d) of uprooted plants for winter fuel.

The Trans-Himalayan rangeland maintains a very low plant biomass, and there is a substantial overlap in habitat and resource use by wild ungulates and livestock [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. The results of the present study give new insight into the extent of this habitat overlap between livestock, blue sheep and the omnivorous brown bear. Given the limited plant resources in this region [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26], it is likely that there is substantial competition for available foods between the overlapping species. For this reason, in addition to the threat that brown bears pose to livestock and that blue sheep pose to crops [

3], this overlap should be taken into consideration in the preparation of species management and land use plans in the Trans-Himalaya region. Further detailed studies should be conducted to understand the ecological interactions between the co-occurring wildlife species within the shared habitats.

In addition to resource availability, brown bear habitat selection is influenced by a suite of dynamic factors, including risk of predation and human disturbance [

27,

28,

29,

30]. In the present study, we did not find any signs of brown bears closer than 5 km from villages and human settlements, most likely because of the combined effects of over-exploitation of resources and perceived threat from humans. Blue sheep and livestock generally use the middle slope positions for grazing, as do Himalayan marmots. Himalayan marmots also prefer areas with good food availability and high sun exposure [

30]; these locations were also selected by the brown bear. Blue sheep used higher elevations than smaller livestock, but overlapped extensively with yaks. Although the brown bears overlapped more with blue sheep than with domestic livestock, there was still a sharing of habitat, and this is likely to increase the conflict between brown bears and local people (by retaliatory killing), if this overlap causes bears to depredate livestock more frequently.

Brown bears are of high conservation value in Nepal, and in the present paper we have reported an initial draft of an evidence-based recommendation for a conservation action plan for this species. However, more information is needed, particularly regarding the status and distribution of brown bears in the far western regions of the country. We propose the implementation of a three-stage program of conservation activities for brown bear conservation in Nepal. This program should include: (a) Detailed research activities in and outside the protected areas of Nepal; (b) support for local livelihood and conservation awareness; and (c) the strengthening of local capacity and a reduction in human-wildlife conflict, including poaching, in the region. However, it needs to be noted that within the brown bear distribution of the Himalayan region there is a diversity of cultures, religions and economic statuses. For this reason, site-specific brown bear conservation research action plans should be prepared and implemented.