Enduring Gene Flow, Despite an Extremely Low Effective Population Size, Supports Hope for the Recovery of the Globally Endangered Lear’s Macaw

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

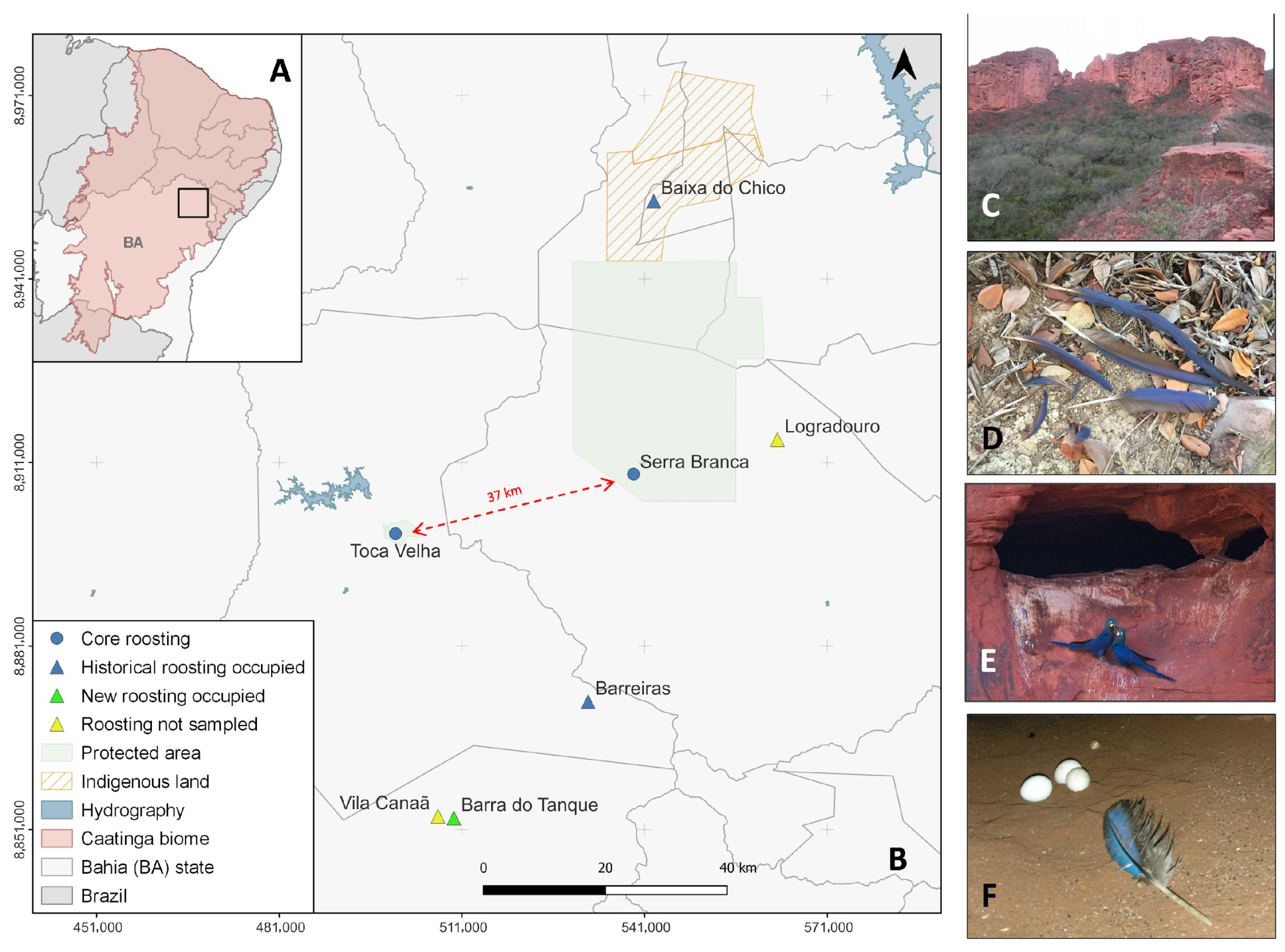

2.1. Study Area and Field Sampling

2.2. DNA Extraction, Sex Determination, and Microsatellite Genotyping

2.3. Individual Identification

2.4. Genetic Diversity

2.5. Genetic Differentiation, Migration Rates, and Population History

2.6. Effective Population Size

3. Results

3.1. Non-Invasive Biological Sampling and Individual Identification

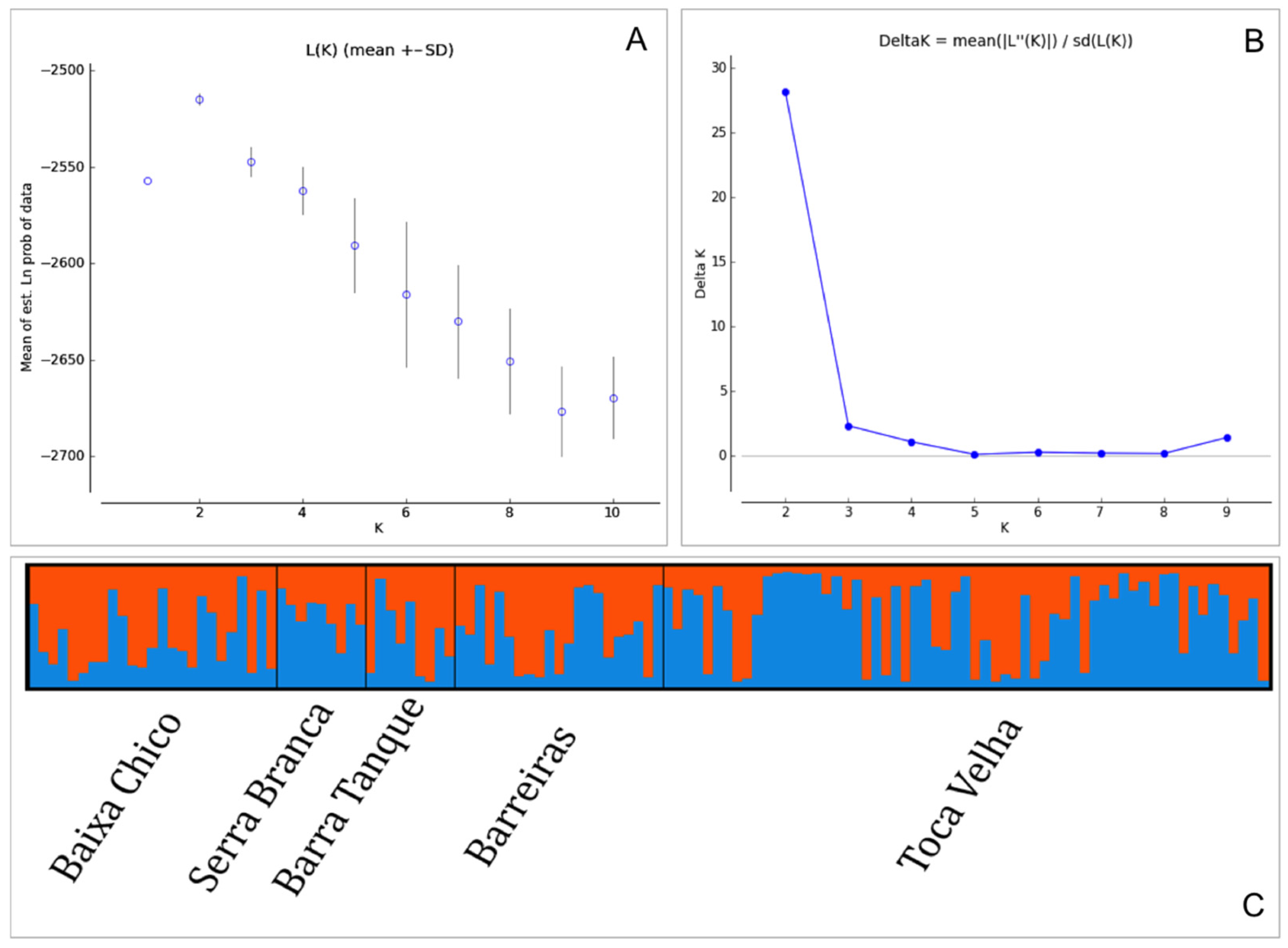

3.2. Genetic Diversity, Differentiation, Migration Rates, and Population History

3.3. Effective Population Size

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olah, G.; Butchart, S.H.M.; Symes, A.; Guzmán, I.M.; Cunningham, R.; Brightsmith, D.J.; Heinsohn, R. Ecological and Socio-Economic Factors Affecting Extinction Risk in Parrots. Biodivers. Conserv. 2016, 25, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olah, G.; Smith, B.T.; Joseph, L.; Banks, S.C.; Heinsohn, R. Parrot Conservation and Advancing Genetic Methods. Diversity 2021, 13, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankham, R. Genetics and extinction. Biol. Conserv. 2005, 126, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankham, R. Genetic rescue of small-inbred populations: Meta-analysis reveals large and consistent benefits of gene flow. Mol. Ecol. 2015, 24, 2610–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, L.S.; Smouse, P.E. Demographic consequences of inbreeding in remnant populations. Am. Nat. 1994, 144, 412–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, B.W.; Tonkyn, D.W.; O’Grady, J.J.; Frankham, R. Contribution of inbreeding to extinction risk in threatened species. Conserv. Ecol. 2002, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Chen, N.; Cosgrove, E.J.; Bowman, R.; Fitzpatrick, J.W.; Clark, A.G. Dynamics of reduced genetic diversity in increasingly fragmented populations of Florida scrub jays, Aphelocoma coerulescens. Evol. Appl. 2022, 15, 1018–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Summers, J.; Cosgrove, E.J.; Bowman, R.; Fitzpatrick, J.W.; Chen, N. Density dependence maintains long-term stability despite increased isolation and inbreeding in the Florida Scrub-Jay. Ecol. Lett. 2024, 27, e14483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankham, R. Genetic adaptation to captivity in species conservation programs. Mol. Ecol. 2008, 17, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, T.R.A.; Presti, F.T.; Cruz, V.P.; Wasko, A.P. Genetic analysis of the endangered Hyacinth Macaw (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus) based on mitochondrial markers: Different conservation efforts are required for different populations. J. Ornithol. 2019, 160, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D.A.; Robinson, Z.L.; Funk, W.C.; Fitzpatrick, S.W.; Allendorf, F.W.; Tallmon, D.A.; Whiteley, A.R. The exciting potential and remaining uncertainties of genetic rescue. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2019, 34, 1070–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lande, R. Mutation and conservation. Conserv. Biol. 1995, 9, 782–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.; Conery, J.; Burger, R. Mutation accumulation and the extinction of small populations. Am. Nat. 1995, 146, 489–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazave, E.; Chang, D.; Clark, A.G.; Keinan, A. Population growth inflates the per-individual number of deleterious mutations and reduces their mean effect. Genetics 2013, 195, 969–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sick, H.; Teixeira, D.M. Discovery of the home of the Indigo Macaw in Brazil: With notes on field identification of “blue” macaws. Am. Birds 1980, 34, 118–212. [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita, C. Field observations and comments on the Indigo Macaw Anodorhynchus leari, a highly endangered species from northeastern Brazil. Wilson Bull. 1987, 99, 280–282. [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento, J.L.X.; Barros, Y.M.; Yamashita, C.; Alves, E.M.; Bianchi, C.A.; Paiva, A.A.; Menezes, A.C.; Alves, D.M.; Silva, J.; Lins, L.V.; et al. Censos de araras-azuis-de-Lear Anodorhynchus leari na natureza. Tangara 2001, 1, 135–138. [Google Scholar]

- Pacífico, E.C.; Denes, F.V.; Barbosa, A.E.; Filadelfo, T.; Souza, A.E.B.A.; Tella, J.L.; Beissinger, S. Improving inference of population size from heterogeneous bird counting data to understand the population trend: A study case of the endangered Lear’s macaw. 2026; Manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Munn, C. Lear’s Macaw: A second population confirmed. PsittaScene World Parrot Trust 1995, 7, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Pacífico, E.C.; Efstathion, C.A.; Filadelfo, T.; Horsburgh, R.; Alves, R.C.; Paschotto, F.R.; Denes, F.V.; Gilardi, J.; Tella, J.L. Experimental removal of invasive Africanized honeybees increased breeding population size of the endangered Lear’s Macaw. Pest Manag. Sci. 2020, 76, 4141–4149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olah, G.; Stojanovic, D.; Webb, M.H.; Waples, R.S.; Heinsohn, R. Comparison of three techniques for genetic estimation of effective population size in a critically endangered parrot. Anim. Conserv. 2020, 24, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacífico, E.C.; Barbosa, E.A.; Filadelfo, T.; Oliveira, K.G.; Silveira, L.F.; Tella, J.L. Breeding to non-breeding population ratio and breeding performance of the globally endangered Lear’s Macaw Anodorhynchus leari: Conservation and monitoring implications. Bird Conserv. Int. 2014, 24, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presti, F.T.; Meyer, J.; Antas, P.T.Z.; Guedes, N.M.R.; Miyaki, C.Y. Non-invasive genetic sampling for molecular sexing and microsatellite genotyping of hyacinth macaw Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2013, 36, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olah, G.; Heinsohn, R.G.; Brightsmith, D.J.; Espinoza, J.R.; Peakall, R. Validation of non-invasive genetic tagging in two large macaw species (Ara macao and A. chloropterus) of the Peruvian Amazon. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 2016, 8, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, G.; Morinha, F.; Roques, S.; Hiraldo, F.; Rojas, A.; Tella, J.L. Fine-scale genetic structure in the critically endangered red-fronted macaw in the absence of geographic and ecological barriers. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beissinger, S.R.; Wunderle, J.M., Jr.; Meyers, J.M.; Saether, B.; Engen, S. Anatomy of a bottleneck: Diagnosing factors limiting population growth in the Puerto Rican Parrot. Ecol. Monogr. 2008, 78, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinerstein, E.; Olson, D.; Joshi, A.; Vynne, C.; Burgess, N.D.; Wikramanayake, E.; Hahn, N.; Palminteri, S.; Hedao, P.; Noss, R.; et al. An ecoregion-based approach to protecting half the terrestrial realm. BioScience 2017, 67, 534–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, M.F.; Nic Lughadha, E.; de Araújo, F.S.; Martins, F.R. A Phytogeographical Metaanalysis of the Semiarid Caatinga Domain in Brazil. Bot. Rev. 2016, 82, 91–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.M.C.; Barbosa, L.C.F.; Leal, I.R.; Tabarelli, M. The Caatinga: Understanding the Challenges. In Caatinga: The Largest Tropical Dry-Forest Region in South America, 1st ed.; Silva, J.M.C., Leal, I.R., Tabarelli, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, A.C.; Souza, A.F. Aridity drives plant biogeographical sub regions in the Caatinga, the largest tropical dry forest and woodland block in South America. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, M.F.; Cardoso, D.; Queiroz, L.P. An updated plant checklist of the Brazilian Caatinga seasonally dry forest and woodlands reveals high species richness and endemism. J. Arid Environ. 2020, 174, 104079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhardt, K.J.; Brightsmith, D.; Powell, G.; Waits, L.P. Molted feathers from clay licks in Peru provide DNA for three large macaws (Ara ararauna, A. chloropterus, and A. macao). J. Field Ornithol. 2009, 80, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacífico, E.C.; Sánchez-Montes, G.; Miyaki, C.Y.; Tella, J.L. Isolation and characterization of 15 new microsatellite markers for the globally Endangered Lear’s macaw Anodorhynchus leari. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 8279–8285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantock, T.M.; Prys-Jones, R.T.P.; Lee, P.L.M. New and improved molecular sexing for museum bird specimens. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2008, 8, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuelke, M. An economic method for the fluorescent labeling of PCR fragments. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000, 18, 233–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, C.; Fumagalli, L. Polymorphic DNA microsatellite markers for forensic individual identification and parentage analyses of seven threatened species of parrots (family Psittacidae). PeerJ 2016, 4, e2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peakall, R.; Smouse, P.E. GENALEX 6: Genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2006, 11, 288–295. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, M.; Rousset, F. GENEPOP version 1.2: Population genetics software for exact tests and ecumenicism. J. Hered. 1995, 86, 248–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, W.R. Analyzing tables of statistical tests. Evolution 1989, 43, 223–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, K.; McGinnity, P.; Cross, T.F.; Crozier, W.W.; Prodöhl, P.A. diveRsity: An R package for the estimation and exploration of population genetics parameters and their associated errors. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2013, 4, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedrick, P.W. A standardized genetic differentiation measure. Evolution 2005, 59, 1633–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, L. GST and its relatives do not measure differentiation. Mol. Ecol. 2008, 17, 4015–4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, J.K.; Stephens, M.; Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 2000, 155, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falush, D.; Stephens, M.; Pritchard, J.K. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: Linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics 2003, 164, 1567–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evanno, G.; Regnaut, S.; Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: A simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 2005, 14, 2611–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earl, D.A.; vonHoldt, B.M. STRUCTURE HARVESTER: A website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 2012, 4, 359–361. [Google Scholar]

- Kopelman, N.M.; Mayzel, J.; Jakobsson, M.; Rosenberg, N.A.; Mayrose, I. Clumpak: A program for identifying clustering modes and packaging population structure inferences across K. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2015, 15, 1179–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.A.; Rannala, B. Bayesian inference of recent migration rates using multilocus genotypes. Genetics 2003, 163, 1177–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaut, A.; Drummond, A.J.; Xie, D.; Baele, G.; Suchard, M.A. Posterior summarization in Bayesian phylogenetics using Tracer 1.7. Syst. Biol. 2018, 67, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meirmans, P.G. Nonconvergence in Bayesian estimation of migration rates. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2014, 14, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faubet, P.; Waples, R.S.; Gaggiotti, O. Evaluating the performance of a multilocus Bayesian method for the estimation of migration rates. Mol. Ecol. 2007, 16, 1149–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piry, S.; Luikart, G.; Cornuet, J.M. BOTTLENECK: A computer program for detecting recent reductions in the effective population size using allele frequency data. J. Hered. 1999, 90, 502–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, O.R.; Wang, J. COLONY: A program for parentage and sibship inference from multilocus genotype data. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2010, 10, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. A new method for estimating effective population sizes from a single sample of multilocus genotypes. Mol. Ecol. 2009, 18, 2148–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Montes, G.; Wang, J.; Ariño, A.H.; Vizmanos, J.L.; Martínez-Solano, I. Reliable effective number of breeders/adult census size ratios in seasonal-breeding species: Opportunity for integrative demographic inferences based on capture-mark-recapture data and multilocus genotypes. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 7, 10301–10314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, C.; Waples, R.S.; Peel, D.; Macbeth, G.M.; Tillett, B.J.; Ovenden, J.R. NEESTIMATOR v2: Re-implementation of software for the estimation of contemporary effective population size (Ne) from genetic data. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2014, 14, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankham, R.; Bradshaw, C.J.A.; Brook, B.W. Genetics in conservation management: Revised recommendations for the 50/500 rules, Red List criteria and population viability analyses. Biol. Conserv. 2014, 170, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Ortíz, F.A.; Solórzano, S.; Arizmendi, M.C.; Dávila-Aranda, P.; Oyama, K. Genetic diversity and structure of the military macaw Ara militaris in Mexico: Implications for conservation. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2017, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, C.I.; Martinez, M.A.; Acosta, D.; Diaz-Luque, J.A.; Berkunsky, I.; Lamberski, N.L.; Cruz-Nieto, J.; Russello, M.A.; Wright, T.F. Genetic diversity and population structure of two endangered Neotropical parrots inform in-situ and ex-situ conservation strategies. Diversity 2021, 13, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nader, W.; Werner, D.; Wink, M. Genetic diversity of scarlet macaws Ara macao in reintroduction studies for threatened populations in Costa Rica. Biol. Conserv. 1999, 87, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monge, O.; Schmidt, K.; Vaughan, C.; Gutiérrez-Espeleta, G. Genetic Patterns and Conservation of the Scarlet Macaw Ara macao in Costa Rica. Conserv. Genet. 2016, 17, 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beebee, T.J.C. A comparison of single-sample effective size estimators using empirical toad (Bufo calamita) population data: Genetic compensation and population size-genetic diversity correlations. Mol. Ecol. 2009, 18, 4790–4797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, A.E.A.; Tella, J.L. How much does it cost to save a species from extinction? Costs and rewards of conserving the Lear’s Macaw. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2019, 6, 190190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasotto, L.D.; Pacífico, E.C.; Paschotto, F.R.; Filadelfo, T.; Couto, M.B.; Sousa, A.E.; Mantovani, P.; Silveira, L.F.; Ascensão, F.; Tella, J.L.; et al. Power line electrocution as an overlooked threat to the Lear’s Macaw (Anodorhynchus leari). IBIS 2023, 165, 998–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornuet, J.M.; Luikart, G. Description and power analysis of two tests for detecting recent population bottlenecks from allele frequency data. Genetics 1996, 144, 2001–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waples, R.S. Genetic estimates of contemporary effective population size: To what time periods do the estimates apply? Mol. Ecol. 2005, 14, 3335–3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornejo, J. Lear’s Macaw (Anodorhynchus leari) International Studbook and Population Analysis; Captive Program for the Lear’s Macaw; ICMBio: Brasília, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Young, A.M.; Hobson, E.A.; Bingaman, L.L.; Wright, T.F. Survival on the ark: Life-history trends in captive parrots. Anim. Conserv. 2012, 15, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinman-Ruiz, D.; Martinez-Cruz, B.; Soriano, L.; Lucena-Perez, M.; Cruz, F.; Villanueva, B.; Fernández, J.; Godoy, J.A. Novel efficient genome-wide SNP panels for the conservation of the highly endangered Iberian lynx. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vili, N.; Nemesházi, E.; Kovács, S.; Horváth, M.; Kalmár, L.; Szabó, K. Factors affecting DNA quality in feathers used for non-invasive sampling. J. Ornithol. 2013, 154, 587–5955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Volo, S.B.; Reynolds, R.T.; Douglas, M.R.; Antolin, M.F. An improved extraction method to increase DNA yield from molted feathers. Condor 2008, 110, 762–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, V.V.F.; Scariot, A.; Sevilha, A.C. Livestock and agriculture affect recruitment and the structure of a key palm for people and an endangered bird in semi-arid lands. J. Arid Environ. 2023, 217, 105036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, F.; Banks, S.C.; Edworthy, M.; Stojanovic, D.; Langmore, N.E.; Heinsohn, R. Using conservation genetics to prioritize management options for an endangered songbird. Heredity 2023, 130, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankham, R.; Ballou, J.D.; Briscoe, D.A. Introduction to Conservation Genetics, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gautschi, D.; Heinsohn, R.; Ortiz-Catedral, L.; Stojanovic, D.; Wilson, M.; Crates, R.; Macgregor, N.A.; Olsen, P.; Neaves, L. Genetic diversity and inbreeding in an endangered island-dwelling parrot population following repeated population bottlenecks. Conserv. Genet. 2024, 25, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Locality | Nobs | Ncol | Next | Nsex | Ngen | Nindiv |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toca Velha | 750 | 438 | 260 | 62 | 63 | 52 |

| Serra Branca | 1000 | 203 | 96 | 10 | 10 | 9 |

| Baixa do Chico | 80 | 269 | 100 | 32 | 31 | 25 |

| Barreiras | 30 | 95 | 65 | 25 | 25 | 21 |

| Barra do Tanque | 150 | 181 | 100 | 26 | 9 | 9 |

| Boqueirão da Onça | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Overall | 2010 | 1186 | 621 | 155 | 138 | 116 |

| Marker | Dye | N. Alleles | Size Range | HWE | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ale176 | NED | 4 | 134–154 | 0 | Pacífico et al. 2020b [33] |

| Alea20 | PET | 5 | 190–206 | 0 | Jan and Fumagalli, 2016 [36] |

| Alea23 | VIC | 7 | 201–221 | 0 | Jan and Fumagalli, 2016 [36] |

| Alea28 | 6-FAM | 8 | 219–251 | 0 | Jan and Fumagalli, 2016 [36] |

| Ale281 | PET | 5 | 102–130 | 1 | Pacífico et al. 2020b [33] |

| Alea4 | 6-FAM | 5 | 139–175 | 0 | Jan and Fumagalli, 2016 [36] |

| Alea5 | VIC | 6 | 135–155 | 0 | Jan and Fumagalli, 2016 [36] |

| Ale606 | 6-FAM | 2 | 087–089 | 0 | Pacífico et al. in 2020b [33] |

| Genetic Diversity | Ne (SF Method) | Ne (LD Method) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locality | Nindiv | AR | HO | HE | PA | FIS | Sib. Prior | Inbreeding | Ne (95% CI) | Lfreq | Ne (95% CI) |

| Toca Velha | 52 | 5.33 (0.55) | 0.72 (0.07) | 0.67 (0.06) | 0 | −0.05 (0.02) | No | No | 29 (18–51) | 0 | 26 (15–50) |

| 30 (19–52) | |||||||||||

| Yes | 28 (17–48) | 0.01 | 26 (15–50) | ||||||||

| 30 (19–51) | |||||||||||

| Weak | No | 24 (15–45) | 0.02 | 26 (15–49) | |||||||

| 22 (13–40) | |||||||||||

| Yes | 24 (15–45) | 0.05 | 21 (12–41) | ||||||||

| 22 (13–40) | |||||||||||

| Serra Branca | 9 | 4.44 (0.34) | 0.56 (0.06) | 0.60 (0.05) | 0 | 0.04 (0.08) | No | No | 48 (16–∞) | 0 | 20 (6–∞) |

| 48 (15–∞) | |||||||||||

| Yes | 29 (12–∞) | 0.01 | 20 (6–∞) | ||||||||

| 29 (12–∞) | |||||||||||

| Weak | No | 9 (4–46) | 0.02 | 20 (6–∞) | |||||||

| 9 (3–45) | |||||||||||

| Yes | 9 (4–46) | 0.05 | 20 (6–∞) | ||||||||

| 9 (4–64) | |||||||||||

| Baixa do Chico | 25 | 4.89 (0.48) | 0.67 (0.05) | 0.66 (0.03) | 0 | −0.02 (0.04) | No | No | 32 (18–64) | 0 | 45 (16–∞) |

| 32 (18–66) | |||||||||||

| Yes | 32 (17–64) | 0.01 | 45 (16–∞) | ||||||||

| 32 (18–61) | |||||||||||

| Weak | No | 14 (7–30) | 0.02 | 45 (16–∞) | |||||||

| 14 (8–31) | |||||||||||

| Yes | 14 (7–30) | 0.05 | 45 (14–∞) | ||||||||

| 14 (8–31) | |||||||||||

| Barreiras | 21 | 5.33 (0.55) | 0.61 (0.06) | 0.63 (0.05) | 1 | 0.04 (0.03) | No | No | 26 (14–59) | 0 | 96 (28–∞) |

| 26 (14–57) | |||||||||||

| Yes | 26 (14–58) | 0.01 | 96 (28–∞) | ||||||||

| 26 (14–59) | |||||||||||

| Weak | No | 14 (7–30) | 0.02 | 96 (28–∞) | |||||||

| 14 (7–33) | |||||||||||

| Yes | 14 (7–30) | 0.05 | 36 (14–∞) | ||||||||

| 14 (7–33) | |||||||||||

| Barra do Tanque | 9 | 4.00 (0.33) | 0.64 (0.07) | 0.59 (0.05) | 0 | −0.08 (0.06) | No | No | 29 (11–∞) | 0 | 8 (3–94) |

| 29 (12–∞) | |||||||||||

| Yes | 29 (11–∞) | 0.01 | 8 (3–94) | ||||||||

| 29 (10–∞) | |||||||||||

| Weak | No | 5 (2–20) | 0.02 | 8 (3–94) | |||||||

| 5 (2–20) | |||||||||||

| Yes | 5 (2–20) | 0.05 | 8 (3–94) | ||||||||

| Overall | 116 | 4.80 (0.21) | 0.64 (0.03) | 0.63 (0.02) | - | −0.01 (0.02) | No | No | 54 (38–80) | 0 | 64 (45–98) |

| 51 (36–77) | |||||||||||

| Yes | 49 (34–73) | 0.01 | 62 (42–99) | ||||||||

| 59 (41–85) | |||||||||||

| Weak | No | 50 (34–75) | 0.02 | 56 (37–89) | |||||||

| 56 (39–85) | |||||||||||

| Yes | 50 (34–75) | 0.05 | 80 (43–201) | ||||||||

| 56 (39–85) | |||||||||||

| Toca Velha | Serra Branca | Baixa Do Chico | Barreiras | Barra Do Tanque | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toca Velha | - | −0.007 | 0.037 | 0.047 | 0.100 |

| Serra Branca | 0 | - | −0.010 | −0.008 | 0.031 |

| Baixa do Chico | 0.009 | −0.002 | - | 0.002 | 0.039 |

| Barreiras | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0 | - | 0.040 |

| Barra do Tanque | 0.038 | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.020 | - |

| Toca Velha | Serra Branca | Baixa Do Chico | Barreiras | Barra Do Tanque | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toca Velha | 0.684 (0.017) | 0.105 (0.053) | 0.071 (0.035) | 0.070 (0.052) | 0.070 (0.021) |

| Serra Branca | 0.105 (0.061) | 0.710 (0.039) | 0.075 (0.052) | 0.078 (0.051) | 0.032 (0.028) |

| Baixa do Chico | 0.115 (0.061) | 0.071 (0.047) | 0.694 (0.025) | 0.064 (0.051) | 0.058 (0.034) |

| Barreiras | 0.062 (0.047) | 0.059 (0.039) | 0.091 (0.047) | 0.712 (0.033) | 0.076 (0.037) |

| Barra do Tanque | 0.037 (0.035) | 0.109 (0.058) | 0.059 (0.045) | 0.085 (0.056) | 0.710 (0.035) |

| Locality | IAM | TPM | SMM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Toca Velha | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.004 |

| Serra Branca | 0.844 | 0.902 | 0.250 |

| Baixa do Chico | 0.004 | 0.020 | 0.039 |

| Barreiras | 0.250 | 0.527 | 1.000 |

| Barra do Tanque | 0.313 | 0.473 | 0.945 |

| Overall | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.004 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pacífico, E.C.; Sánchez-Montes, G.; Paschotto, F.R.; Filadelfo, T.; Hiraldo, F.; Godoy, J.A.; Miyaki, C.Y.; Tella, J.L. Enduring Gene Flow, Despite an Extremely Low Effective Population Size, Supports Hope for the Recovery of the Globally Endangered Lear’s Macaw. Diversity 2026, 18, 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18020087

Pacífico EC, Sánchez-Montes G, Paschotto FR, Filadelfo T, Hiraldo F, Godoy JA, Miyaki CY, Tella JL. Enduring Gene Flow, Despite an Extremely Low Effective Population Size, Supports Hope for the Recovery of the Globally Endangered Lear’s Macaw. Diversity. 2026; 18(2):87. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18020087

Chicago/Turabian StylePacífico, Erica C., Gregorio Sánchez-Montes, Fernanda R. Paschotto, Thiago Filadelfo, Fernando Hiraldo, José A. Godoy, Cristina Y. Miyaki, and José L. Tella. 2026. "Enduring Gene Flow, Despite an Extremely Low Effective Population Size, Supports Hope for the Recovery of the Globally Endangered Lear’s Macaw" Diversity 18, no. 2: 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18020087

APA StylePacífico, E. C., Sánchez-Montes, G., Paschotto, F. R., Filadelfo, T., Hiraldo, F., Godoy, J. A., Miyaki, C. Y., & Tella, J. L. (2026). Enduring Gene Flow, Despite an Extremely Low Effective Population Size, Supports Hope for the Recovery of the Globally Endangered Lear’s Macaw. Diversity, 18(2), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18020087