Climate Refugia of Endangered Mammals in South Korea Under SSP Climate Scenarios: An Ensemble Species Distribution Modeling Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Species Occurrence Data

2.3. Environmental Variables

2.4. Species Distribution Modeling (SDM)

2.5. Climate Change Scenarios and Future Projections

2.6. Habitat Suitability Classification and Species Richness

3. Results

3.1. Model Performance Evaluation

3.2. Species-Specific Model Performance

3.3. Environmental Variables Importance

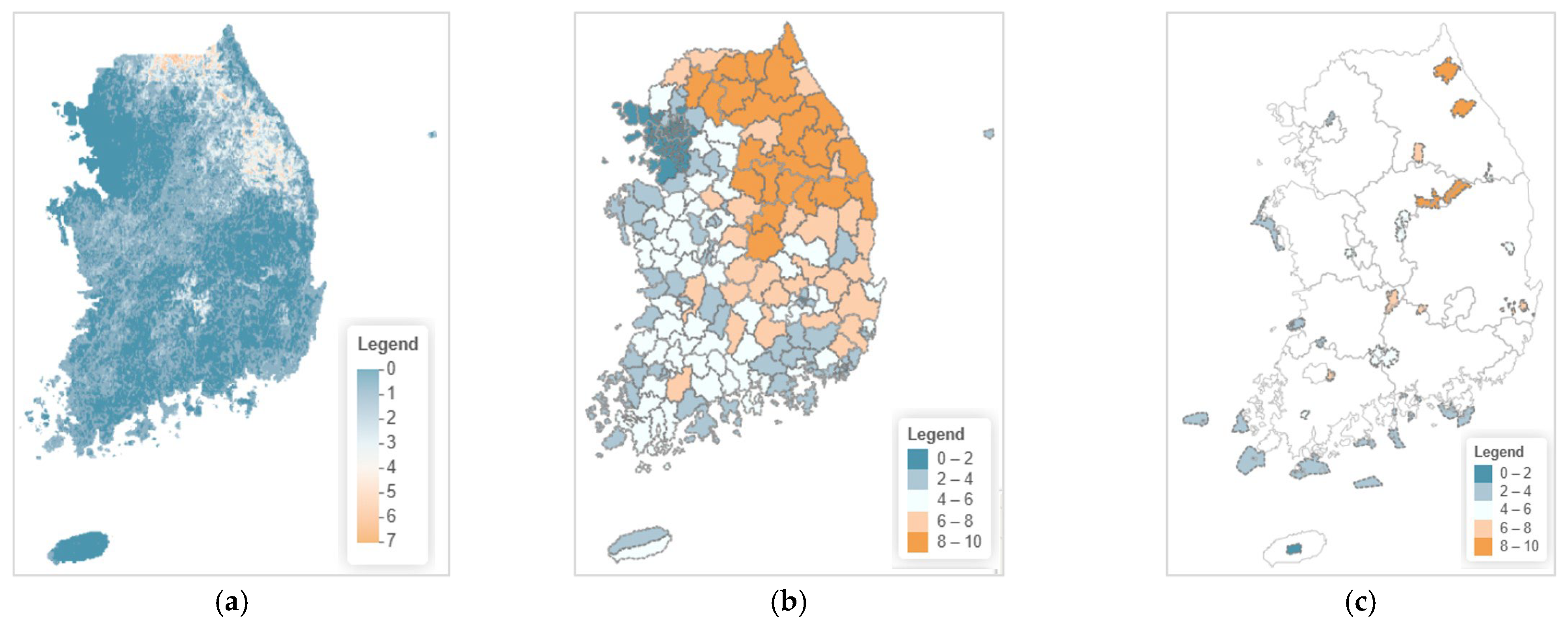

3.4. Current Species Richness Distribution

3.4.1. Overall Species Richness Distribution Pattern

3.4.2. Current Species Richness by Local Government Units

3.4.3. Current Species Richness by National Parks

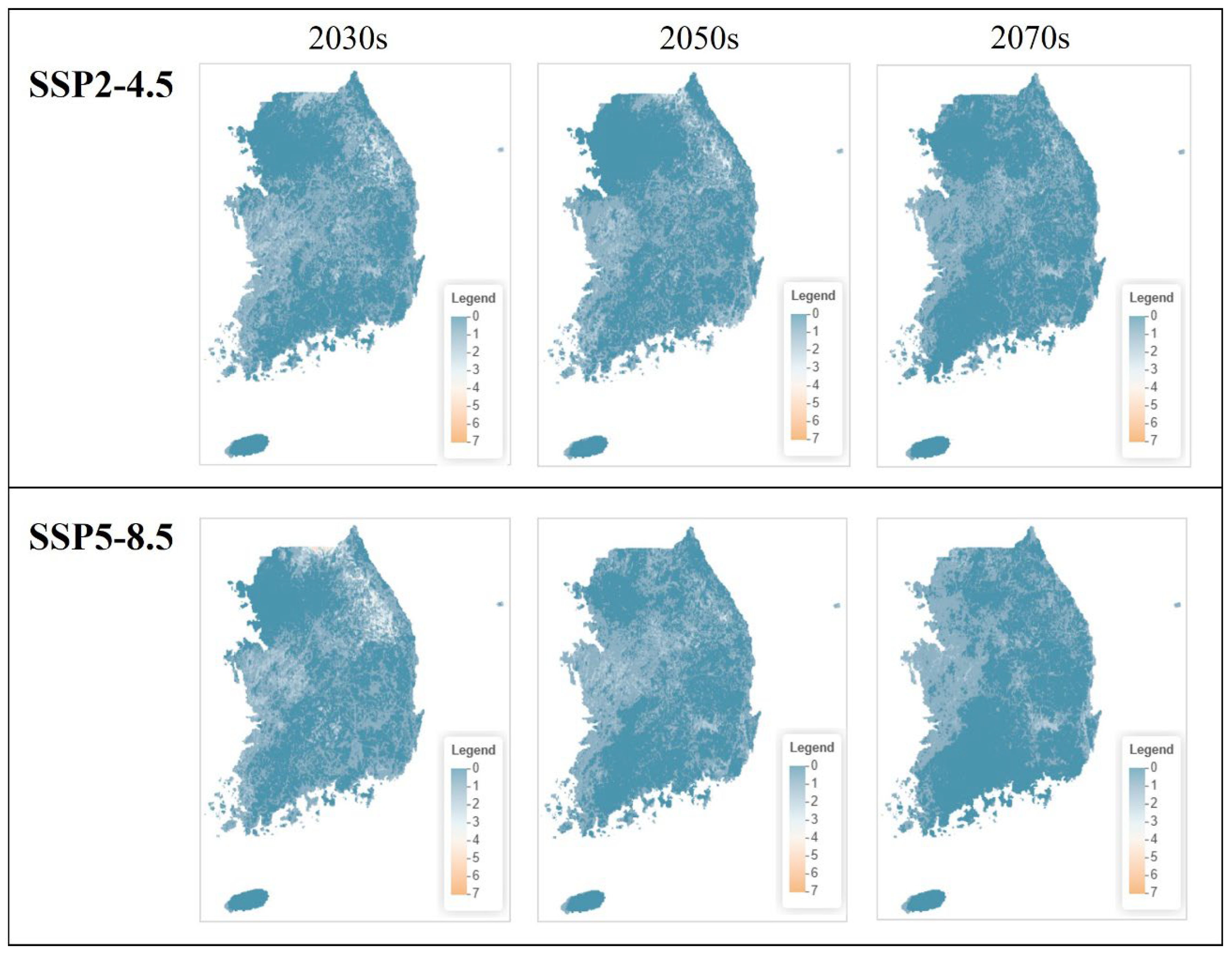

3.5. Future Habitat Changes Predictions

3.5.1. National-Level Species Richness Change

3.5.2. Projected Species Richness by Local Government Units Under SSP Scenarios

3.5.3. Projected Species Richness by National Parks Under SSP Scenarios

3.5.4. Comparison Between Scenarios and Time Periods

4. Discussion

4.1. Superiority of Ensemble Modeling

4.2. Species-Specific Model Performance Differences

4.3. Environmental Variables and Species Ecology

4.4. Species Richness Patterns and Conservation Implications

4.4.1. Ecological Importance of the Baekdudaegan

4.4.2. Role of National Parks in Conservation

4.4.3. Habitat Fragmentation and Decline in Lowland Species Richness

4.4.4. Local Government-Level Conservation Priorities

4.4.5. Need for an Integrated Conservation Strategy

4.5. Climate Change Projections and Conservation Strategies

4.5.1. Species Richness Change Patterns by Scenario

4.5.2. Species-Specific Climate Change Impacts

4.5.3. Identification of Priority Conservation Areas

4.5.4. Climate Adaptation Strategies

4.6. Study Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| TSS | True Skill Statistic |

| SDM | Species distribution model |

| BIO | Bioclimatic variable |

| ANN | Artificial neural network |

| CTA | Classification tree analysis |

| DEM | Digital elevation model |

| EM | Ensemble mean |

| EMW | AUC-weighted ensemble mean |

| FDA | Flexible discriminant analysis |

| GAM | Generalized additive model |

| GBM | Generalized boosted model |

| GLM | Generalized linear model |

| IUCN | International Union for Conservation of Nature |

| KMA | Korea Meteorological Administration |

| MAXENT | Maximum entropy |

| MARS | Multivariate adaptive regression splines |

| ME | Ministry of Environment (Korea) |

| NGII | National Geographic Information Institute |

| NIE | National Institute of Ecology |

| RF | Random forest |

| SSP | Shared Socioeconomic Pathway |

| SRE | Surface range envelope |

| WAMIS | Water Management Information System |

References

- Ceballos, G.; Ehrlich, P.R.; Barnosky, A.D.; García, A.; Pringle, R.M.; Palmer, T.M. Accelerated modern human-induced species losses: Entering the sixth mass extinction. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1400253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowie, R.H.; Bouchet, P.; Fontaine, B. The Sixth Mass Extinction: Fact, fiction or speculation? Biol. Rev. 2022, 97, 640–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnosky, A.D.; Matzke, N.; Tomiya, S.; Wogan, G.O.U.; Swartz, B.; Quental, T.B.; Marshall, C.; McGuire, J.L.; Lindsey, E.L.; Maguire, K.C.; et al. Has the Earth’s sixth mass extinction already arrived? Nature 2011, 471, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPBES. Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pimm, S.L.; Jenkins, C.N.; Abell, R.; Brooks, T.M.; Gittleman, J.L.; Joppa, L.N.; Raven, P.H.; Roberts, C.M.; Sexton, J.O. The biodiversity of species and their rates of extinction, distribution, and protection. Science 2014, 344, 1246752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Living Planet Report 2020; World Wildlife Fund: Gland, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bellard, C.; Bertelsmeier, C.; Leadley, P.; Thuiller, W.; Courchamp, F. Impacts of climate change on the future of biodiversity. Ecol. Lett. 2012, 15, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.C.; Hill, J.K.; Ohlemüller, R.; Roy, D.B.; Thomas, C.D. Rapid range shifts of species associated with high levels of climate warming. Science 2011, 333, 1024–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, A.D.; Hamilton, M.J.; Boyer, A.G.; Brown, J.H.; Ceballos, G. Multiple ecological pathways to extinction in mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 10702–10705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipper, J.; Chanson, J.S.; Chiozza, F.; Cox, N.A.; Hoffmann, M.; Katariya, V.; Lamoreux, J.; Rodrigues, A.S.L.; Stuart, S.N.; Temple, H.J.; et al. The status of the world’s land and marine mammals: Diversity, threat, and knowledge. Science 2008, 322, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, N.M.; Brudvig, L.A.; Clobert, J.; Davies, K.F.; Gonzalez, A.; Holt, R.D.; Lovejoy, T.E.; Sexton, J.O.; Austin, M.P.; Collins, C.D.; et al. Habitat fragmentation and its lasting impact on Earth’s ecosystems. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreychev, A.; Kuznetsov, V.; Lapshin, A. Distribution and Population Density of the Russian Desman (Desmana moschata L., Talpidae, Insectivora) in the Middle Volga of Russia. For. Stud. Metsanduslikud Uurim. 2019, 71, 48–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisfield, V.E.; Blanchet, F.G.; Raudsepp-Hearne, C.; Gravel, D. How and Why Species Are Rare: Towards an Understanding of the Ecological Causes of Rarity. Ecography 2024, 2024, e07037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guisan, A.; Zimmermann, N.E. Predictive habitat distribution models in ecology. Ecol. Model. 2000, 135, 147–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elith, J.; Leathwick, J.R. Species distribution models: Ecological explanation and prediction across space and time. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2009, 40, 677–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, J. Mapping Species Distributions: Spatial Inference and Prediction; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Guisan, A.; Thuiller, W.; Zimmermann, N.E. Habitat Suitability and Distribution Models: With Applications in R; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Araújo, M.B.; Peterson, A.T. Uses and misuses of bioclimatic envelope modeling. Ecology 2012, 93, 1527–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, H.; Soberón, J.; Peterson, A.T. No silver bullets in correlative ecological niche modelling: Insights from testing among many potential algorithms for niche estimation. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2015, 6, 1126–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.G.; Thuiller, W.; Araújo, M.B.; Martinez-Meyer, E.; Brotons, L.; McClean, C.; Miles, L.; Segurado, P.; Dawson, T.P.; Lees, D.C. Model-based uncertainty in species range prediction. J. Biogeogr. 2006, 33, 1704–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M.B.; New, M. Ensemble forecasting of species distributions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007, 22, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmion, M.; Parviainen, M.; Luoto, M.; Heikkinen, R.K.; Thuiller, W. Evaluation of consensus methods in predictive species distribution modelling. Divers. Distrib. 2009, 15, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuiller, W.; Lafourcade, B.; Engler, R.; Araújo, M.B. BIOMOD—A platform for ensemble forecasting of species distributions. Ecography 2009, 32, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, T.; Elith, J.; Guillera-Arroita, G.; Lahoz-Monfort, J.J. A review of evidence about use and performance of species distribution modelling ensembles like BIOMOD. Divers. Distrib. 2019, 25, 839–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stohlgren, T.J.; Ma, P.; Kumar, S.; Rocca, M.; Morisette, J.T.; Jarnevich, C.S.; Benson, N. Ensemble habitat mapping of invasive plant species. Risk Anal. 2010, 30, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Nie, X.; Chen, F.; Guo, N.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, S.; Huang, Y.; Xie, Y. Field Survey Data for Conservation: Evaluating Suitable Habitat of Chinese Pangolin at the County-Level in Eastern China (2000–2040). Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e11512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedin, I.; Mukherjee, T.; Kim, A.R.; Lee, S.R.; Kim, H.-W.; Kundu, S. Fragile Futures: Evaluating Habitat and Climate Change Response of Hog Badgers (Arctonyx) in the Conservation Landscape of Mainland Asia. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e70160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raqeeb, M.; Shoukat, H.B.; Kabir, M.; Mushtaq, A.; Qasim, S.; Mahmood, T.; Belant, J.L.; Akrim, F. Forecasting Impacts of Climate Change on Barking Deer Distribution in Pakistan. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 29035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.K.; Jeon, S.W. Estimating the value of ecological connectivity of the Korean Peninsula. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2015, 17, 417–433. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, W.S. Criteria for selecting the vertical vegetation zones in high mountains in Korea. J. Korean Geogr. Soc. 2004, 39, 629–645. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.K.; Lee, W.S.; Kim, H.G.; Cho, Y.H.; Choi, S.H. Distribution and management of Korean endemic plants along the Baekdudaegan mountain range. J. Ecol. Environ. 2011, 34, 333–345. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.H.; Lee, Y.H.; Lee, G.; Lee, D.-H.; Adhikari, P. Predicting Impacts of Climate Change on Northward Range Expansion of Invasive Weeds in South Korea. Plants 2021, 10, 1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Environment. Endangered Wild Species List (Revised in 2022); Ministry of Environment: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2022. (In Korean)

- National Institute of Biological Resources (NIBR). 2022 National Biodiversity Statistics; National Institute of Biological Resources: Incheon, Republic of Korea, 2023. (In Korean)

- Korea Meteorological Administration. Climate Change Scenario Report for IPCC AR6; Korea Meteorological Administration: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2024.

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chun, J.H.; Lee, C.B. Assessing the effects of climate change on the geographic distribution of Pinus densiflora in Korea using ecological niche model. Korean J. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 20, 219–233. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, P.; Jeon, J.Y.; Kim, H.W.; Shin, M.-S.; Adhikari, P.; Seo, C. Potential Impact of Climate Change on Plant Invasion in the Republic of Korea. J. Ecol. Environ. 2019, 43, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, Y.J.; Kira, T. Distribution of forest vegetation and climate in the Korean Peninsula: I. Distribution of some indices of thermal climate. Jpn. J. Ecol. 1975, 25, 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, H.K.; Choi, T.Y. Distribution and management of the Baekdudaegan mountain range ecosystem in Korea. Korean J. Environ. Ecol. 2004, 18, 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Boria, R.A.; Olson, L.E.; Goodman, S.M.; Anderson, R.P. Spatial filtering to reduce sampling bias can improve the performance of ecological niche models. Ecol. Model. 2014, 275, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijmans, R.J. Cross-validation of species distribution models: Removing spatial sorting bias and calibration with a null model. Ecology 2012, 93, 679–688. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer-Schadt, S.; Niedballa, J.; Pilgrim, J.D.; Schröder, B.; Lindenborn, J.; Reinfelder, V.; Stillfried, M.; Heckmann, I.; Scharf, A.K.; Augeri, D.M.; et al. The importance of correcting for sampling bias in MaxEnt species distribution models. Divers. Distrib. 2013, 19, 1366–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Meteorological Administration. Climate Information Portal: Climate Change Scenario Data. Available online: https://www.climate.go.kr (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Fick, S.E.; Hijmans, R.J. WorldClim 2: New 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 4302–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, A.; Reuter, H.I.; Nelson, A.; Guevara, E. Hole-Filled SRTM for the Globe Version 4, Available from the CGIAR-CSI SRTM 90m Database. 2008. Available online: http://srtm.csi.cgiar.org (accessed on 20 September 2023).

- Dormann, C.F.; Elith, J.; Bacher, S.; Buchmann, C.; Carl, G.; Carré, G.; Marquéz, J.R.G.; Gruber, B.; Lafourcade, B.; Leitão, P.J.; et al. Collinearity: A review of methods to deal with it and a simulation study evaluating their performance. Ecography 2013, 36, 27–46. [Google Scholar]

- Thuiller, W.; Georges, D.; Gueguen, M.; Engler, R.; Breiner, F. biomod2: Ensemble Platform for Species Distribution Modeling. R Package Version 4.2-5. 2020. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=biomod2 (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Elith, J.; Graham, C.H.; Anderson, R.P.; Dudík, M.; Ferrier, S.; Guisan, A.; Hijmans, R.J.; Huettmann, F.; Leathwick, J.R.; Lehmann, A.; et al. Novel methods improve prediction of species’ distributions from occurrence data. Ecography 2006, 29, 129–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J.; Anderson, R.P.; Schapire, R.E. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol. Model. 2006, 190, 231–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar]

- Barbet-Massin, M.; Jiguet, F.; Albert, C.H.; Thuiller, W. Selecting pseudo-absences for species distribution models: How, where and how many? Methods Ecol. Evol. 2012, 3, 327–338. [Google Scholar]

- Araújo, M.B.; Pearson, R.G.; Thuiller, W.; Erhard, M. Validation of species–climate impact models under climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 2005, 11, 1504–1513. [Google Scholar]

- Allouche, O.; Tsoar, A.; Kadmon, R. Assessing the accuracy of species distribution models: Prevalence, kappa and the true skill statistic (TSS). J. Appl. Ecol. 2006, 43, 1223–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; White, M.; Newell, G. Selecting thresholds for the prediction of species occurrence with presence-only data. J. Biogeogr. 2013, 40, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swets, J.A. Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science 1988, 240, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, B.C.; Tebaldi, C.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Eyring, V.; Friedlingstein, P.; Hurtt, G.; Knutti, R.; Kriegler, E.; Lamarque, J.F.; Lowe, J.; et al. The Scenario Model Intercomparison Project (ScenarioMIP) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 2017, 9, 3461–3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi, K.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Kriegler, E.; Edmonds, J.; O’Neill, B.C.; Fujimori, S.; Bauer, N.; Calvin, K.; Dellink, R.; Fricko, O.; et al. The Shared Socioeconomic Pathways and their energy, land use, and greenhouse gas emissions implications: An overview. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 42, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebaldi, C.; Debeire, K.; Eyring, V.; Fischer, E.; Fyfe, J.; Friedlingstein, P.; Knutti, R.; Lowe, J.; O’Neill, B.; Sanderson, B.; et al. Climate model projections from the Scenario Model Intercomparison Project (ScenarioMIP) of CMIP6. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2021, 12, 253–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elith, J.; Kearney, M.; Phillips, S. The art of modelling range-shifting species. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2010, 1, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppel, G.; Van Niel, K.P.; Wardell-Johnson, G.W.; Yates, C.J.; Byrne, M.; Mucina, L.; Schut, A.G.; Hopper, S.D.; Franklin, S.E. Refugia: Identifying and understanding safe havens for biodiversity under climate change. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2012, 21, 393–404. [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft, M.B.; Gollan, J.R.; Warton, D.I.; Ramp, D. A novel approach to quantify and locate potential biodiversity refugia from climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 2012, 18, 1866–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elith, J.; Leathwick, J.R.; Hastie, T. A working guide to boosted regression trees. J. Anim. Ecol. 2008, 77, 802–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, D.R.; Edwards, T.C.; Beard, K.H.; Cutler, A.; Hess, K.T.; Gibson, J.; Lawler, J.J. Random forests for classification in ecology. Ecology 2007, 88, 2783–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J.; Dudík, M. Modeling of species distributions with Maxent: New extensions and a comprehensive evaluation. Ecography 2008, 31, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buisson, L.; Thuiller, W.; Casajus, N.; Lek, S.; Grenouillet, G. Uncertainty in ensemble forecasting of species distribution. Glob. Change Biol. 2010, 16, 1145–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenouillet, G.; Buisson, L.; Casajus, N.; Lek, S. Ensemble modelling of species distribution: The effects of geographical and environmental ranges. Ecography 2011, 34, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porfirio, L.L.; Harris, R.M.B.; Lefroy, E.C.; Hugh, S.; Gould, S.F.; Lee, G.; Bindoff, N.L.; Mackey, B. Improving the use of species distribution models in conservation planning and management under climate change. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, J.M.; Jetz, W. Effects of species’ ecology on the accuracy of distribution models. Ecography 2007, 30, 135–151. [Google Scholar]

- Syphard, A.D.; Franklin, J. Differences in spatial predictions among species distribution modeling methods vary with species traits and environmental predictors. Ecography 2009, 32, 907–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydell, J.; Arita, H.T.; Santos, M.; Granados, J. Acoustic identification of insectivorous bats (order Chiroptera) of Yucatan, Mexico. J. Zool. 2009, 257, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, W.T.; Stafford, R.; Brashares, J.S. The effects of small sample size and sample bias on threshold selection and accuracy assessment of species distribution models. Ecography 2012, 35, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruuk, H. Otters: Ecology, Behaviour and Conservation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, P.A.; Graham, C.H.; Master, L.L.; Albert, D.L. The effect of sample size and species characteristics on performance of different species distribution modeling methods. Ecography 2006, 29, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, H.; Jones, G. Ground validation of presence-only modelling with rare species: A case study on barbastelles Barbastella barbastellus (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae). J. Appl. Ecol. 2010, 47, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, E.E.; Theobald, D.M.; Ver Hoef, J.M. Geostatistical modelling on stream networks: Developing valid covariance matrices based on hydrologic distance and stream flow. Freshw. Biol. 2011, 52, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, H.; Tarroso, P.; Jones, G. Predicted impact of climate change on European bats in relation to their biogeographic patterns. Glob. Change Biol. 2010, 16, 561–576. [Google Scholar]

- Körner, C. The use of ‘altitude’ in ecological research. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007, 22, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCain, C.M.; Grytnes, J.A. Elevational gradients in species richness. In Encyclopedia of Life Sciences; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.B.; Newman, C.; Xu, W.T.; Buesching, C.D.; Zalewski, A.; Kaneko, Y.; Macdonald, D.W.; Xie, Z.Q. Biogeography of Chinese martens: Niche overlap analysis predicts future expansion of pine marten (Martes martes) at the expense of sable (Martes zibellina) in Northeast China. Divers. Distrib. 2008, 17, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar]

- Mysterud, A.; Yoccoz, N.G.; Stenseth, N.C.; Langvatn, R. Effects of age, sex and density on body weight of Norwegian red deer: Evidence of density-dependence in body composition. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 2001, 268, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovari, S.; Ferretti, F.; Corazza, M.; Minder, I.; Troiani, N.; Ferrari, C.; Saddi, A. Unexpected consequences of reintroductions: Competition between increasing red deer and threatened Apennine chamois. Anim. Conserv. 2009, 17, 488–498. [Google Scholar]

- Shackleton, D.M. Wild Sheep and Goats and Their Relatives: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan for Caprinae; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Xiao, F.; Cui, G.; Li, M. Habitat suitability evaluation of Sichuan takin (Budorcas taxicolor tibetana) using remote sensing and GIS technology. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2018, 38, 1966–1973. [Google Scholar]

- Selonen, V.; Painter, J.N.; Rantala, S.; Hanski, I.K. Mating system and reproductive success in the flying squirrel Pteromys volans. J. Mammal. 2010, 94, 1283–1291. [Google Scholar]

- Reunanen, P.; Nikula, A.; Monkkonen, M.; Hurme, E.; Inkeröinen, J. Biogeography of voles in Fennoscandian boreal forests: The role of climate and habitat quality. J. Biogeogr. 2002, 29, 1533–1543. [Google Scholar]

- Augustine, D.J.; McNaughton, S.J. Ungulate effects on the functional species composition of plant communities: Herbivore selectivity and plant tolerance. J. Wildl. Manag. 1998, 62, 1165–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, I.C.; Muff, S.; de Jongh, A.; Kranz, A.; Bontadina, F. Flexible habitat selection paves the way for a recovery of otter populations in the European Alps. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 199, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, F.; Clare, E.L.; Symondson, W.O.C.; Keišs, O.; Pētersons, G. Diet of the insectivorous bat Pipistrellus nathusii during autumn migration and summer residence. Mol. Ecol. 2012, 23, 3672–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, R.T.T.; Alexander, L.E. Roads and their major ecological effects. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1998, 29, 207–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffin, A.W. From roadkill to road ecology: A review of the ecological effects of roads. J. Transp. Geogr. 2007, 15, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altringham, J.D. Bats: From Evolution to Conservation, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Crooks, K.R.; Sanjayan, M. Connectivity Conservation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker, R.J.; Willis, K.J.; Field, R. Scale and species richness: Towards a general, hierarchical theory of species diversity. J. Biogeogr. 2001, 28, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, G.S.; Kim, E.S.; Choi, S.H.; Jeon, S.W. Estimating carbon storage in urban forests of South Korea. Forests 2018, 9, 625. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, A.G.; Gullison, R.E.; Rice, R.E.; da Fonseca, G.A.B. Effectiveness of parks in protecting tropical biodiversity. Science 2001, 291, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaston, K.J.; Jackson, S.F.; Cantú-Salazar, L.; Cruz-Piñón, G. The ecological performance of protected areas. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2008, 39, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.Y.; Jeong, S.; Kim, K.G. Impact of climate change on the habitat of the Winter Olympic Games: Skiing and ski jumping. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1141. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.-S.; Chung, Y.-J.; Moon, Y.-S. Potential Habitat and Priority Conservation Areas for Endangered Species in South Korea. Animals 2025, 15, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongman, R.H.G.; Külvik, M.; Kristiansen, I. European ecological networks and greenways. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 68, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Lee, M.B. Analysis of the landscape ecological changes of mountains in Seoul Metropolitan Area. J. Korean Inst. Landsc. Archit. 2014, 42, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Fahrig, L. Effects of habitat fragmentation on biodiversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2003, 34, 487–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodroffe, R.; Ginsberg, J.R. Edge effects and the extinction of populations inside protected areas. Science 1998, 280, 2126–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clevenger, A.P.; Waltho, N. Factors influencing the effectiveness of wildlife underpasses in Banff National Park, Alberta, Canada. Conserv. Biol. 2000, 14, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margules, C.R.; Pressey, R.L. Systematic conservation planning. Nature 2000, 405, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, R.; Nilsson, C.; Malmqvist, B. Restoring freshwater ecosystems in riverine landscapes: The roles of connectivity and recovery processes. Freshw. Biol. 2007, 52, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissman, A.R.; Lozier, L.; Comendant, T.; Kareiva, P.; Kiesecker, J.M.; Shaw, M.R.; Merenlender, A.M. Conservation easements: Biodiversity protection and private use. Conserv. Biol. 2007, 21, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, T.P.; Jackson, S.T.; House, J.I.; Prentice, I.C.; Mace, G.M. Beyond predictions: Biodiversity conservation in a changing climate. Science 2011, 332, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah, L.; Flint, L.; Syphard, A.D.; Moritz, M.A.; Buckley, L.B.; McCullough, I.M. Fine-grain modeling of species’ response to climate change: Holdouts, stepping-stones, and microrefugia. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2014, 29, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenoir, J.; Bertrand, R.; Comte, L.; Bourgeaud, L.; Hattab, T.; Murienne, J.; Grenouillet, G. Species better track climate warming in the oceans than on land. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 4, 1044–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selonen, V.; Hanski, I.K. Young flying squirrels (Pteromys volans) dispersing in fragmented forests. Behav. Ecol. 2004, 15, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettorelli, N.; Mysterud, A.; Yoccoz, N.G.; Langvatn, R.; Stenseth, N.C. Importance of climatological downscaling and plant phenology for red deer in heterogeneous landscapes. Proc. R. Soc. B 2007, 274, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loarie, S.R.; Duffy, P.B.; Hamilton, H.; Asner, G.P.; Field, C.B.; Ackerly, D.D. The velocity of climate change. Nature 2009, 462, 1052–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.A.; Auerbach, N.A.; Sam, K.; Magini, A.G.; Moss, A.S.L.; Langhans, S.D.; Budiharta, S.; Terzano, D.; Meijaard, E. Conservation research is not happening where it is most needed. PLoS Biol. 2016, 14, e1002413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keppel, G.; Mokany, K.; Wardell-Johnson, G.W.; Phillips, B.L.; Welbergen, J.A.; Reside, A.E. The capacity of refugia for conservation planning under climate change. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2015, 13, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, N.E.; Zavaleta, E.S. Biodiversity management in the face of climate change: A review of 22 years of recommendations. Biol. Conserv. 2009, 142, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenmayer, D.B.; Likens, G.E. The science and application of ecological monitoring. Biol. Conserv. 2010, 143, 1317–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armsworth, P.R.; Acs, S.; Dallimer, M.; Gaston, K.J.; Hanley, N.; Wilson, P. The cost of policy simplification in conservation incentive programs. Ecol. Lett. 2012, 15, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunez, S.; Arets, E.; Alkemade, R.; Verwer, C.; Leemans, R. Assessing the impacts of climate change on biodiversity: Is below 2°C enough? Clim. Change 2019, 154, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soberón, J.; Peterson, A.T. Interpretation of models of fundamental ecological niches and species’ distributional areas. Biodivers. Inform. 2005, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisz, M.S.; Pottier, J.; Kissling, W.D.; Pellissier, L.; Lenoir, J.; Damgaard, C.F.; Dormann, C.F.; Forchhammer, M.C.; Grytnes, J.A.; Guisan, A.; et al. The role of biotic interactions in shaping distributions and realised assemblages of species: Implications for species distribution modelling. Biol. Rev. 2013, 88, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, M.W.; Hofmeyr, M.; O’Brien, J.; Kerley, G.I.H. Prey preferences of the leopard (Panthera pardus). J. Zool. 2006, 270, 298–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cord, A.F.; Klein, D.; Gernandt, D.S.; de la Rosa, J.A.P.; Dech, S. Remote sensing data can improve predictions of species richness by stacked species distribution models: A case study for Mexican pines. J. Biogeogr. 2014, 41, 736–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.S.; Bradley, B.A.; Cord, A.F.; Rocchini, D.; Tuanmu, M.N.; Schmidtlein, S.; Turner, W.; Wegmann, M.; Pettorelli, N. Will remote sensing shape the next generation of species distribution models? Remote Sens. Ecol. Conserv. 2015, 1, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beest, F.M.; Uzal, A.; Vander Wal, E.; Laforge, M.P.; Contasti, A.L.; Colville, D.; McLoughlin, P.D. Increasing density leads to generalization in both coarse-grained habitat selection and fine-grained resource selection in a large mammal. J. Anim. Ecol. 2014, 83, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sala, O.E.; Chapin, F.S.; Armesto, J.J.; Berlow, E.; Bloomfield, J.; Dirzo, R.; Huber-Sanwald, E.; Huenneke, L.F.; Jackson, R.B.; Kinzig, A.; et al. Global biodiversity scenarios for the year 2100. Science 2000, 287, 1770–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jetz, W.; Wilcove, D.S.; Dobson, A.P. Projected impacts of climate and land-use change on the global diversity of birds. PLoS Biol. 2007, 5, e157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titeux, N.; Henle, K.; Mihoub, J.B.; Regos, A.; Geijzendorffer, I.R.; Cramer, W.; Verburg, P.H.; Brotons, L. Biodiversity scenarios neglect future land-use changes. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 22, 2505–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rounsevell, M.D.A.; Reginster, I.; Araújo, M.B.; Carter, T.R.; Dendoncker, N.; Ewert, F.; House, J.I.; Kankaanpää, S.; Leemans, R.; Metzger, M.J.; et al. A coherent set of future land use change scenarios for Europe. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2006, 114, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engler, R.; Randin, C.F.; Vittoz, P.; Czáka, T.; Beniston, M.; Zimmermann, N.E.; Guisan, A. Predicting future distributions of mountain plants under climate change: Does dispersal capacity matter? Ecography 2009, 32, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, J.M.J.; Delgado, M.; Bocedi, G.; Baguette, M.; Bartoń, K.; Bonte, D.; Boulangeat, I.; Hodgson, J.A.; Kubisch, A.; Penteriani, V.; et al. Dispersal and species’ responses to climate change. Oikos 2013, 122, 1532–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavergne, S.; Mouquet, N.; Thuiller, W.; Ronce, O. Biodiversity and climate change: Integrating evolutionary and ecological responses of species and communities. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2010, 41, 321–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuiller, W.; Guéguen, M.; Renaud, J.; Karger, D.N.; Zimmermann, N.E. Uncertainty in ensembles of global biodiversity scenarios. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.M.B.; Grose, M.R.; Lee, G.; Bindoff, N.L.; Porfirio, L.L.; Fox-Hughes, P. Climate projections for ecologists. WIREs Clim. Change 2014, 5, 621–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Order | Family | Species (Scientific Name) | ME Grade * | IUCN Status ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artiodactyla | Bovidae | Naemorhedus caudatus | I | VU |

| Cervidae | Cervus nippon hortulorum | I | LC | |

| Moschidae | Moschus moschiferus | I | VU | |

| Carnivora | Felidae | Prionailurus bengalensis | II | LC |

| Mustelidae | Lutra lutra | I | NT | |

| Mustelidae | Martes flavigula | II | LC | |

| Chiroptera | Vespertilionidae | Murina ussuriensis | I | LC |

| Vespertilionidae | Myotis rufoniger | I | LC | |

| Vespertilionidae | Plecotus ognevi | II | LC | |

| Rodentia | Sciuridae | Pteromys volans aluco | II | LC |

| Order | Family | No. of Species |

|---|---|---|

| Artiodactyla | Total | 3 |

| Bovidae | 1 | |

| Cervidae | 1 | |

| Moschidae | 1 | |

| Carnivora | Total | 3 |

| Felidae | 1 | |

| Mustelidae | 2 | |

| Chiroptera | Total | 3 |

| Vespertilionidae | 3 | |

| Rodentia | Total | 1 |

| Sciuridae | 1 | |

| Total | 10 |

| Category | Variable Code | Description | Unit | Source | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bioclimatic | BIO1 | Annual mean temperature | °C | KMA | 1 km |

| Bioclimatic | BIO2 | Mean diurnal temperature range | °C | KMA | 1 km |

| Bioclimatic | BIO3 | Isothermality (BIO2/BIO7 × 100; BIO7 = annual temperature range (BIO5 − BIO6)) | - | KMA | 1 km |

| Bioclimatic | BIO12 | Annual precipitation | mm | KMA | 1 km |

| Bioclimatic | BIO13 | Precipitation of wettest month | mm | KMA | 1 km |

| Bioclimatic | BIO14 | Precipitation of driest month | mm | KMA | 1 km |

| Topographic | Elevation | Elevation above sea level | m | SRTM DEM | 90 m (resampled to 1 km) |

| Topographic | Slope | Terrain slope | degree | SRTM DEM | 90 m (resampled to 1 km) |

| Hydrological | Dist_water | Distance to nearest water body | m | WAMIS | 1 km |

| Human activity | Dist_road | Distance to nearest road | m | NGII | 1 km |

| Species | BIO1 | BIO2 | BIO3 | BIO12 | BIO13 | BIO14 | Elev | Slope | D_Road | D_Water |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. flavigula | 3 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 10 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 |

| C. nippon hortulorum | 4 | 10 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 8 | 6 | 2 |

| M. rufoniger | 4 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 10 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 8 |

| M. moschiferus | 3 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 6 |

| N. caudatus | 2 | 5 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 10 | 6 |

| P. bengalensis | 1 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 9 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 5 |

| L. lutra | 2 | 9 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 10 | 3 | 1 |

| M. ussuriensis | 3 | 7 | 6 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 2 | 10 | 4 | 1 |

| P. ognevi | 2 | 9 | 10 | 7 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 4 |

| P. volans aluco | 1 | 3 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lee, J.-H.; Shin, M.-S.; Lee, E.-S.; Lee, J.-S.; Seo, C.-W. Climate Refugia of Endangered Mammals in South Korea Under SSP Climate Scenarios: An Ensemble Species Distribution Modeling Approach. Diversity 2026, 18, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010019

Lee J-H, Shin M-S, Lee E-S, Lee J-S, Seo C-W. Climate Refugia of Endangered Mammals in South Korea Under SSP Climate Scenarios: An Ensemble Species Distribution Modeling Approach. Diversity. 2026; 18(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Jae-Ho, Man-Seok Shin, Eun-Seo Lee, Jae-Seok Lee, and Chang-Wan Seo. 2026. "Climate Refugia of Endangered Mammals in South Korea Under SSP Climate Scenarios: An Ensemble Species Distribution Modeling Approach" Diversity 18, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010019

APA StyleLee, J.-H., Shin, M.-S., Lee, E.-S., Lee, J.-S., & Seo, C.-W. (2026). Climate Refugia of Endangered Mammals in South Korea Under SSP Climate Scenarios: An Ensemble Species Distribution Modeling Approach. Diversity, 18(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/d18010019