Updated List of Oklahoma Tiger Beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) with Notes on Their Distribution and Conservation Status

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

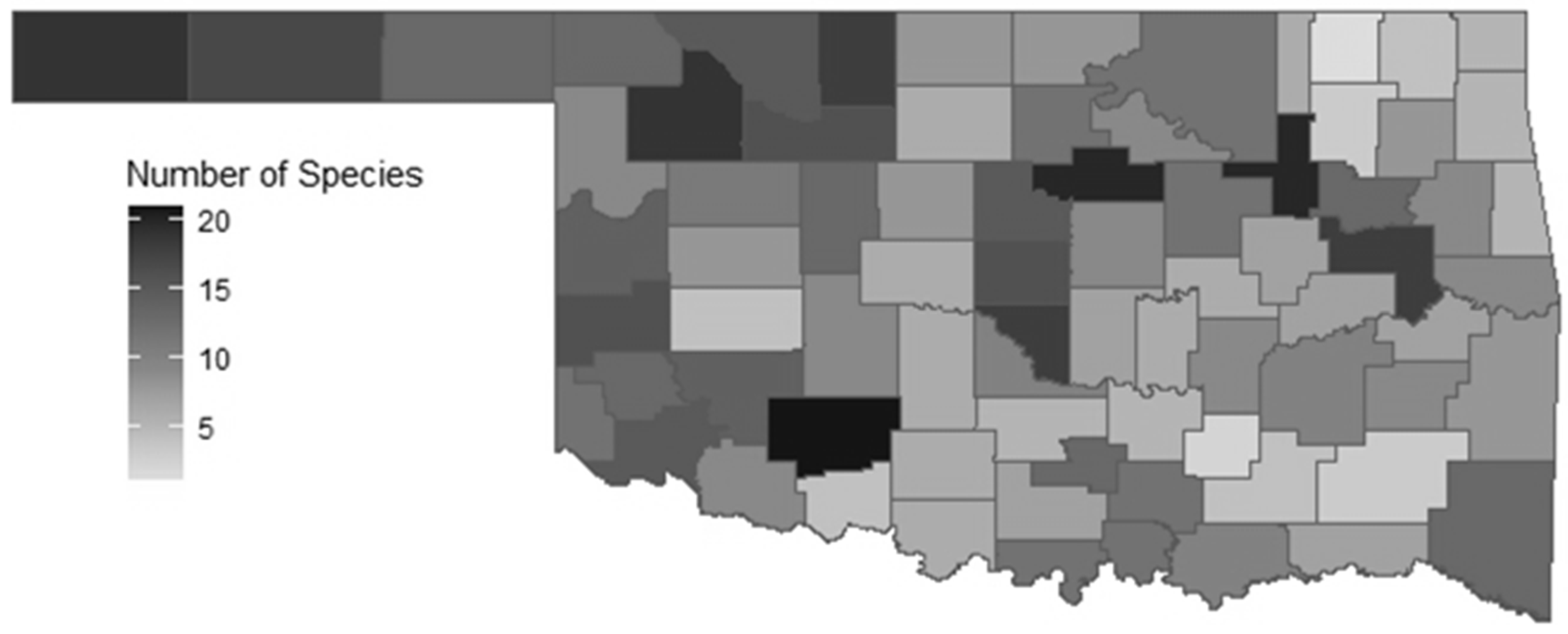

3. Results

4. Discussion

- Species Accounts

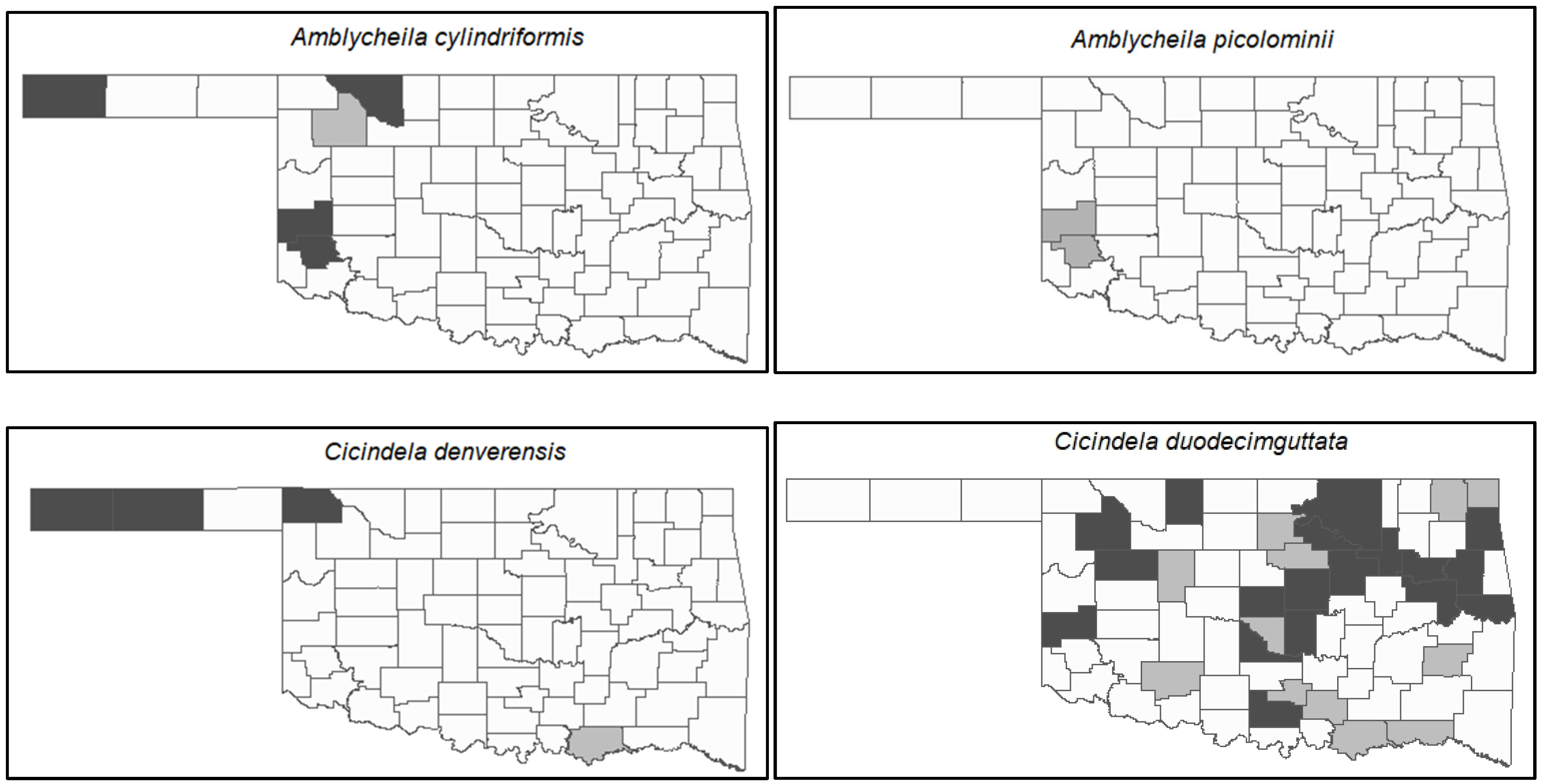

- Amblycheila cylindriformis (Say, 1823) (four novel records, five total records)

- New records: Beckham, Cimarron, Greer, Woods

- Notes: Amblycheila cylindriformis is known from the western half of Oklahoma, where it is typically associated with sloping clay banks. It is likely more widespread throughout Oklahoma, but its nocturnal habits make detection difficult.

- Amblycheila picolominii Reiche, 1840 (0, 2)

- New records: N/A

- Notes: This species was recently documented from Sandy Sanders Wildlife Management Area in southwest Oklahoma, where it cooccurs with A. cylindriformis [13]. Although difficult to detect because of its nocturnal habits, it likely has a limited range in Oklahoma.

- Cicindela denverensis Casey, 1897 (three, five)

- New records: Cimarron, Harper, Texas

- Notes: Uncommon, but its apparent rarity in collections is likely affected by the unpredictable weather of the Oklahoma Panhandle in early spring and late fall, when the species is active. Found on roadcuts and other areas of sloping, bare ground. The historical record from Bryan County is unlikely and may be a misidentified green morph of Cicindela splendida.

- Cicindela duodecimguttata Dejean, 1825 (18, 30)

- New records: Alfalfa, Beckham, Carter, Cherokee, Creek, Delaware, Dewey, Lincoln, McClain, Muskogee, Oklahoma, Osage, Pawnee, Pottawatomie, Sequoyah, Tulsa, Wagoner, Woodward

- Notes: While usually encountered in small numbers, C. duodecimguttata is regularly found in moist habitats, typically associated with clay or mud. In moist sandy habitats, Cicindela repanda is the dominant species.

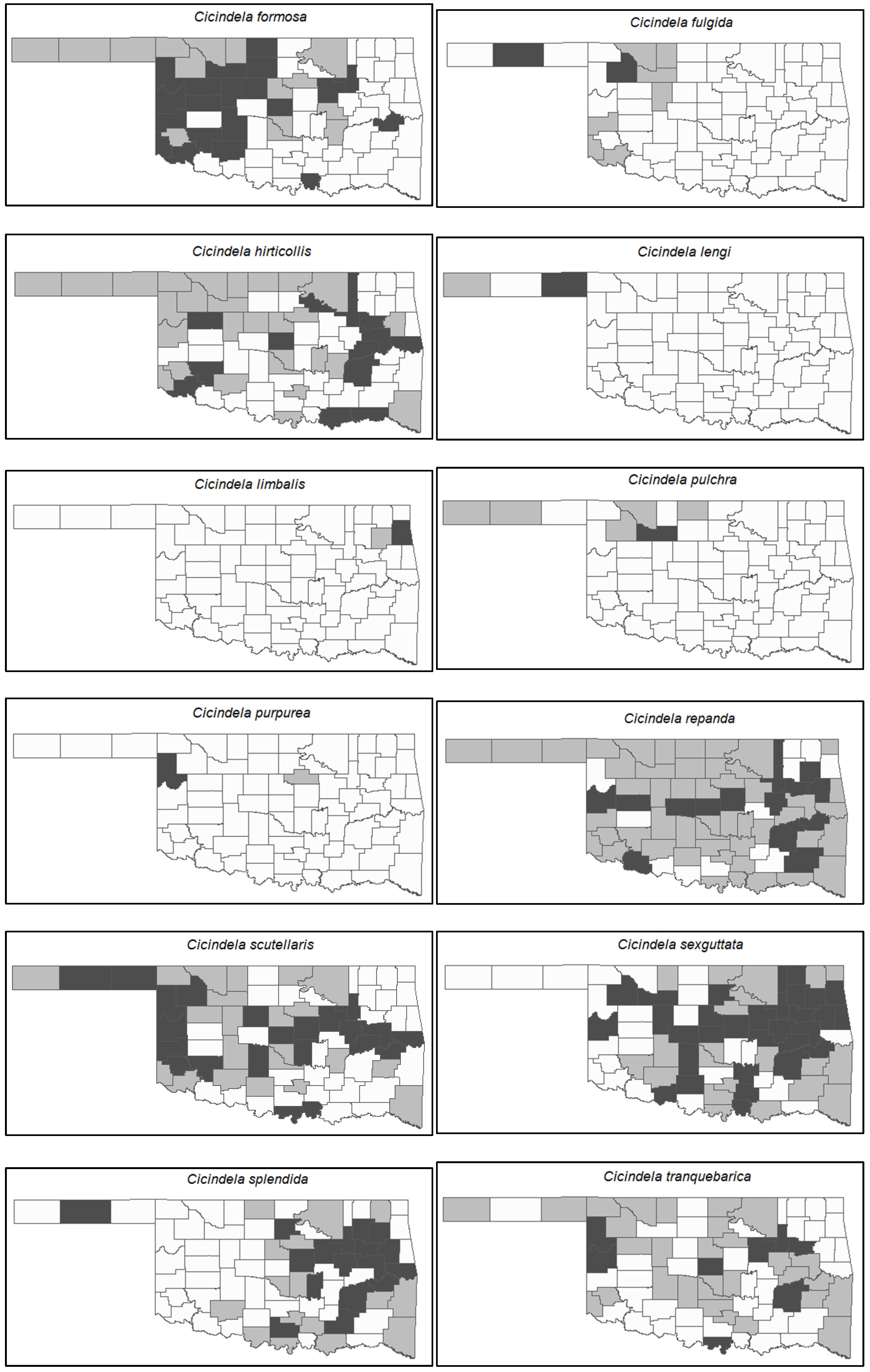

- Cicindela formosa Say, 1817 (20, 34)

- New records: Beckham, Blaine, Caddo, Comanche, Creek, Custer, Dewey, Ellis, Garfield, Grant, Harmon, Haskell, Jackson, Kingfisher, Kiowa, Major, Marshall, Oklahoma, Roger Mills, Tulsa

- Notes: Found in upland sandy areas throughout Oklahoma, usually in more open patches of sand than Cicindela scutellaris or C. tranquebarica. While range maps show it to be absent from the eastern quarter of the state [30], its presence in Haskell County at the Lake Eufaula Dam suggests that it likely ranges further east along the Canadian and Arkansas Rivers.

- Cicindela fulgida Say, 1823 (two, nine)

- New records: Texas, Woodward

- Notes: In contrast to other saline-associated species in Oklahoma, C. fulgida is usually found amongst vegetation at the edges of salt flats. It is not usually found on sand but has been recently photographed by Ian Kanda on sand along the Red River in southwestern Oklahoma (Texas County).

- Cicindela hirticollis Say, 1817 (14, 42)

- New records: Bryan, Choctaw, Dewey, Jackson, Kiowa, McIntosh, Muskogee, Oklahoma, Pawnee, Pittsburg, Sequoyah, Tulsa, Wagoner, Washington

- Notes: Cicindela hirticollis has experienced precipitous declines in response to human disturbance in parts of its range [33,34]. However, it remains fairly common and widespread in Oklahoma, even at sites that are frequently disturbed. It is most abundant on river sandbars but can be common on the beaches of large reservoirs and even on moist salt flats.

- Cicindela lengi Horn, 1908 (one, two)

- New records: Beaver

- Notes: This species was formerly collected from Beaver Dunes, Beaver County, and the vicinity of Kenton and Felt, in Cimarron County. It was most recently collected in 1990 by David Brzoska, who took a large series north and east of Kenton. However, the drying of rivers in the Panhandle, which prevents the deposition of new sand deposits, and the stabilization of existing dunes by vegetation have reduced the amount of available habitat. The only extensive unvegetated dunes are at Beaver Dunes State Park, which remain open because of use by off-road vehicles. Surveys for Cicindela lengi conducted at historical and potential sites in May 2023 and September 2024 failed to find this species, though Cicindela formosa and C. scutellaris were abundant.

- Cicindela limbalis Klug, 1834 (one, two)

- New records: Delaware

- Notes: The first documented record of C. limbalis in Oklahoma occurred when multiple individuals were photographed in Mayes County by Robert Webster, although that site may have since been lost to development [13]. Luckily, the presence of two specimens in the SEMC, collected in Delaware County in 1980 by David Brzoska, suggests that they are more widespread in northeastern Oklahoma and may still be present.

- Cicindela pulchra Say, 1823 (one, six)

- New records: Major

- Notes: This species is found on large, flat patches of bare clay (Figure 4), usually in grasslands without any trees nearby. Its activity is generally tied to recent rainfall, so it can be difficult to find under dry conditions. Recent records are from the areas surrounding Gloss Mountain and Black Mesa State Parks.

- Cicindela purpurea Olivier, 1790 (one, two)

- New records: Ellis

- Notes: Despite being a common species in the northern Great Plains, C. purpurea is rather uncommon in Oklahoma. All recent records come from the Four Canyon Preserve in Ellis County and the surrounding clay roads. Specimens from this population would seem to represent the nominate subspecies, as no black morphs were noted out of 25 specimens collected and many more observed. The middle band was also substantially reduced compared to specimens of C. p. audubonii LeConte collected in Nebraska.

- Cicindela repanda Dejean, 1825 (15, 65)

- New records: Canadian, Cherokee, Custer, Haskell, Lincoln, Mayes, Oklahoma, Okmulgee, Pittsburg, Pushmataha, Roger Mills, Tillman, Tulsa, Wagoner, Washington

- Notes: This species is found anywhere that standing water is adjacent to bare ground, though it is most common in sandy areas, such as beaches and sandbars. It likely occurs in every county in the state.

- Cicindela scutellaris Say, 1823 (22, 44)

- New records: Beaver, Beckham, Creek, Ellis, Grady, Greer, Haskell, Kingfisher, Kiowa, Lincoln, Love, Marshall, McIntosh, Muskogee, Oklahoma, Okmulgee, Pottawatomie, Roger Mills, Sequoyah, Texas, Tulsa, Woodward

- Notes: This species is associated with upland sand deposits, though it is often found in close proximity to rivers. The subspecific classification of populations in Oklahoma is a matter of debate. Pearson et al. [30] depicts the majority of the state as belonging to the nominate subspecies, with influence from C. s. rugata Vaurie, 1950, in the southeast and C. s. lecontei Haldeman, 1853, in the northeast. However, there are no records of C. s. rugata from further north than Wood County, TX, approximately 100 km south of populations along the Red River. However, there seems to be a continuous blending of C. s. flavoviridis Vaurie, 1950, with the nominate subspecies throughout Oklahoma. The vast majority of the state appears to be within an intergrade zone between ssp. scutellaris and ssp. flavoviridis (Figure 5), while counties along the western edge of the state and the panhandle represent nominate C. s. scutellaris. There are no known specimens from the northeastern corner of the state, so the influence of C. s. lecontei is unknown. Melanistic individuals have been photographed twice for a population near Tulsa by Jay Pruett.

- Cicindela sexguttata Fabricius, 1775 (32, 53)

- New records: Adair, Blaine, Canadian, Cherokee, Cotton, Creek, Delaware, Grady, Haskell, Johnson, Kiowa, Lincoln, Logan, Major, Marshall, Mayes, McIntosh, Muskogee, Noble, Nowata, Okfuskee, Oklahoma, Okmulgee, Pittsburg, Pontotoc, Roger Mills, Rogers, Stephens, Tulsa, Wagoner, Washington, Woodward

- Notes: This species is common throughout the eastern half of the state, where it can be found on bare ground in wooded habitats.

- Cicindela splendida Hentz, 1830 (17, 33)

- New records: Atoka, Carter, Cherokee, Creek, Haskell, Lincoln, Mayes, Muskogee, Noble, Okmulgee, Pittsburg, Rogers, Seminole, Sequoyah, Texas, Tulsa, Wagoner

- Notes: While C. splendida is associated with bare clay throughout much of its range, it is surprisingly absent from much of western Oklahoma, where red clay is the dominant soil type. In Oklahoma, it seems to prefer sandy or gravelly clay over pure clay, which likely becomes too hard for the larvae to burrow into or may not offer enough protection during warm summer months.

- Cicindela tranquebarica Herbst, 1806 (8, 38)

- New records: Creek, Ellis, Love, Oklahoma, Pittsburg, Roger Mills, Tulsa, Wagoner

- Notes: This species is usually associated with bare, upland sand in the eastern half of Oklahoma but can also be abundant on saline flats and along water in the western half of the state. Specimens from Alfalfa County tend to have thinner maculations than those from Wisconsin. However, individuals near the Black Mesa region of Cimarron County have the wider maculations associated with C. t. kirbyi LeConte, 1867. Individuals in the Tulsa area occasionally have strongly reduced maculations, with rare individuals exhibiting only a transverse dash for a middle band and a reduced apical lunule (Figure 6).

- Cicindela willistoni LeConte, 1879 (one, four)

- New records: Blaine

- Notes: This species is the most specialized of the salt flat tiger beetles in Oklahoma and thus has the most limited range. The best-documented population occurs at Great Salt Plains National Wildlife Refuge in Alfalfa County. However, access to the other large saline flats in Oklahoma is restricted, and this species could occupy those as well.

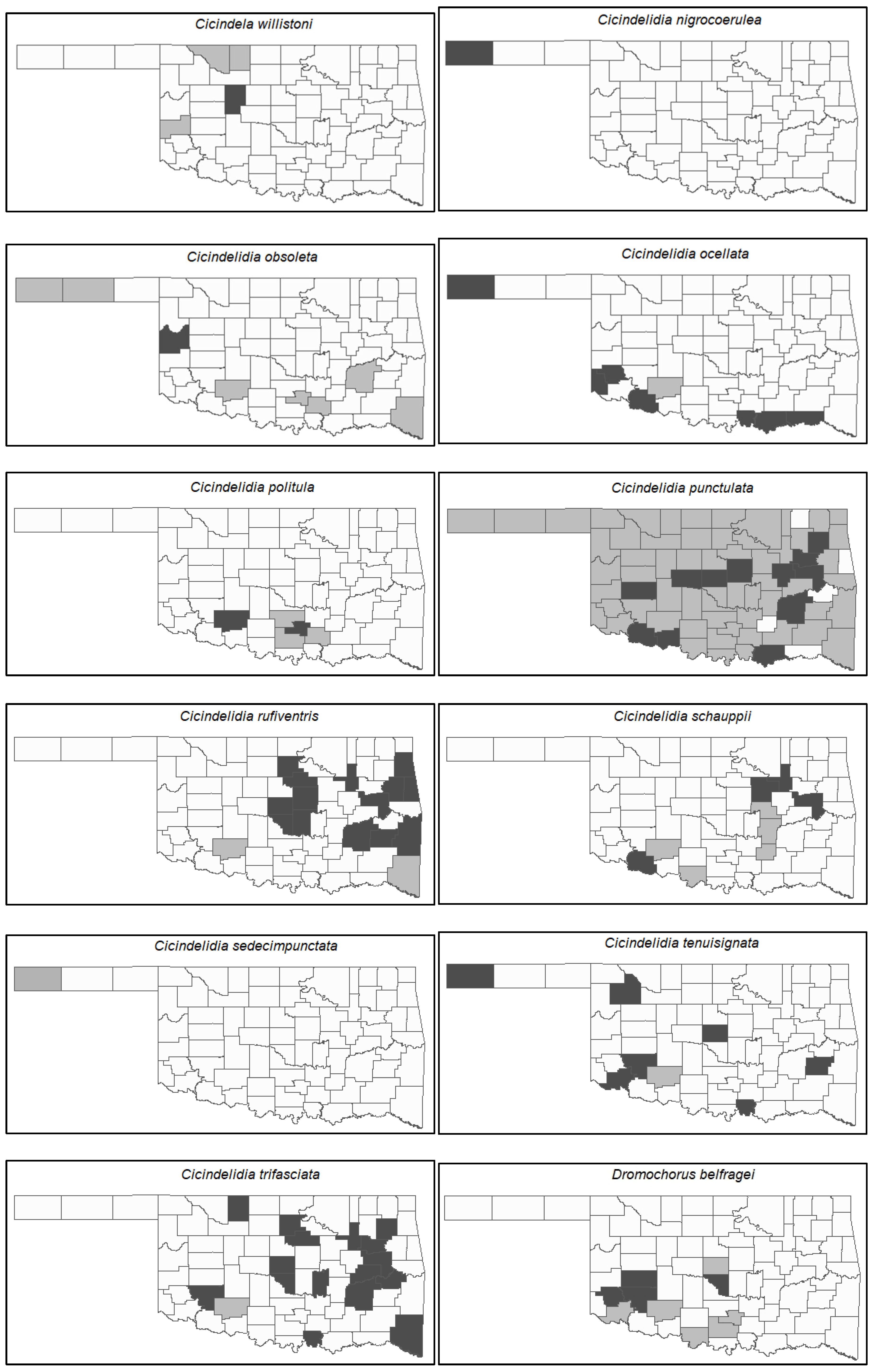

- Cicindelidia nigrocoerulea (LeConte, 1846) (one, one)

- New records: Cimarron

- Notes: This species has been collected near Black Mesa and photographed by R.J. Baltierra in Black Mesa State Park at the northwest corner of Cimarron County. It is usually found near water, often on moist mud.

- Cicindelidia obsoleta (Say, 1823) (one, eight)

- New records: Roger Mills

- Notes: Usually associated with dirt trails in the panhandle (ssp. obsoleta) and with rock outcroppings elsewhere (ssp. vulturina LeConte, 1853). While not depicted in Pearson et al. [30] or Mawdsley [35], the occurrence of C. o. vulturina in Pittsburg and McCurtain counties in southeast Oklahoma suggests that geographically intermediate populations occur between its main range in Texas and the disjunct populations in the Ozark Mountains of Arkansas and Missouri. Populations usually reach peak abundance following heavy rain in late summer.

- Cicindelidia ocellata (Klug, 1834) (seven, eight)

- New records: Bryan, Choctaw, Cimarron, Greer, Harmon, Marshall, Tillman

- Notes: This species is usually associated with water, including roadside ditches, beaches, and muddy sandbars. It is primarily known from the southernmost counties in Oklahoma, but recent records at Black Mesa State Park demonstrate this species’ ability to occur further north, potentially having dispersed in response to climate.

- Cicindelidia politula (LeConte, 1875) (two, five)

- New records: Comanche, Murray

- Notes: This species is usually associated with limestone gravel in the south-central portion of Oklahoma, often on road banks or gravel trails (Figure 7). Compared to other tiger beetles, it seems to occur at relatively low densities.

- Cicindelidia punctulata (Olivier, 1790) (12, 72)

- New records: Bryan, Canadian, Cotton, Lincoln, Mayes, Muskogee, Oklahoma, Okmulgee, Pittsburg, Tulsa, Wagoner, Washita

- Notes: This species is common on bare ground throughout Oklahoma, from sand dunes and saline flats to parking lots. While green forms are most common in the Panhandle, they occur throughout the state, and greenish individuals have been noted as far east as Murray and Wagoner counties.

- Cicindelidia rufiventris (Dejean, 1825) (14, 16)

- New records: Adair, Cherokee, Cleveland, Delaware, Latimer, LeFlore, Lincoln, Muskogee, Noble, Oklahoma, Payne, Pittsburg, Pottawatomie, Tulsa

- Notes: This species typically occurs on partially shaded trails, where it is often associated with either limestone or sandy soil. Populations in the Ouachita Mountains of southeast Oklahoma tend to show strong C. r. cumatilis (LeConte, 1851) influence, with minimal maculations and blue coloring, while populations to the north and west generally have mixed phenotypes.

- Cicindelidia schauppii (Horn, 1876) (four, nine)

- New records: Creek, Muskogee, Tillman, Tulsa

- Notes: This species seems to be associated with gravelly or sandy soil, like C. rufiventris but without any tree cover. It has a scattered range throughout the state. The distribution suggests vagrant individuals, but four specimens were collected together at the Muskogee County site, and beetles were observed at the Creek County site in 2019, 2022, and 2024.

- Cicindelidia sedecimpunctata (Klug, 1834) (0, 1)

- New records: N/A

- Notes: This species is known from the vicinity of Black Mesa and Black Mesa State Park in Cimarron County, Oklahoma. See Harman et al. [13] for more details.

- Cicindelidia tenuisignata (LeConte, 1851) (seven, eight)

- New records: Cimarron, Jackson, Kiowa, Latimer, Marshall, Oklahoma, Woodward

- Notes: Cicindelidia tenuisignata is found primarily near water in southwestern Oklahoma but has been collected as far north as Nebraska [27], so it could potentially be found anywhere in the state. The recent record from Latimer County, collected at Robbers Cave State Park, is one of the easternmost records of this species.

- Cicindelidia trifasciata (Fabricius, 1781) (16, 17)

- New records: Alfalfa, Cleveland, Haskell, Kiowa, Marshall, Mayes, McCurtain, McIntosh, Muskogee, Noble, Oklahoma, Payne, Pittsburg, Sequoyah, Tulsa, Wagoner

- Notes: This species, which is noted for its dispersal abilities [30], has shown the most dramatic range increase in Oklahoma of all tiger beetle species. It has been found in nearly every region of the state, except the Panhandle, and is commonly found along shores of lakes, ponds, and rivers.

- Dromochorus belfragei Sallé, 1877 (6, 10)

- New records: Cleveland, Greer, Kiowa, Washita

- Notes: D. belfragei is found in the southern half of Oklahoma, where it usually occurs in grasslands and shrublands with patches of bare soil, though the records from Washita County were collected at the edge of a crop field. The record from Lincoln County [16] has been reassigned to D. pruininus.

- Dromochorus pruininus Casey, 1897 (two, three)

- New records: Lincoln, Payne

- Notes: Most recent specimens of D. pruininus have come from Gloss Mountain State Park (Figure 8), but given its scattered records throughout the northern half of the state and its occurrence in northern Texas, it is likely more widespread than records indicate. Its small size, flightlessness, and crepuscular occurrence make detection difficult.

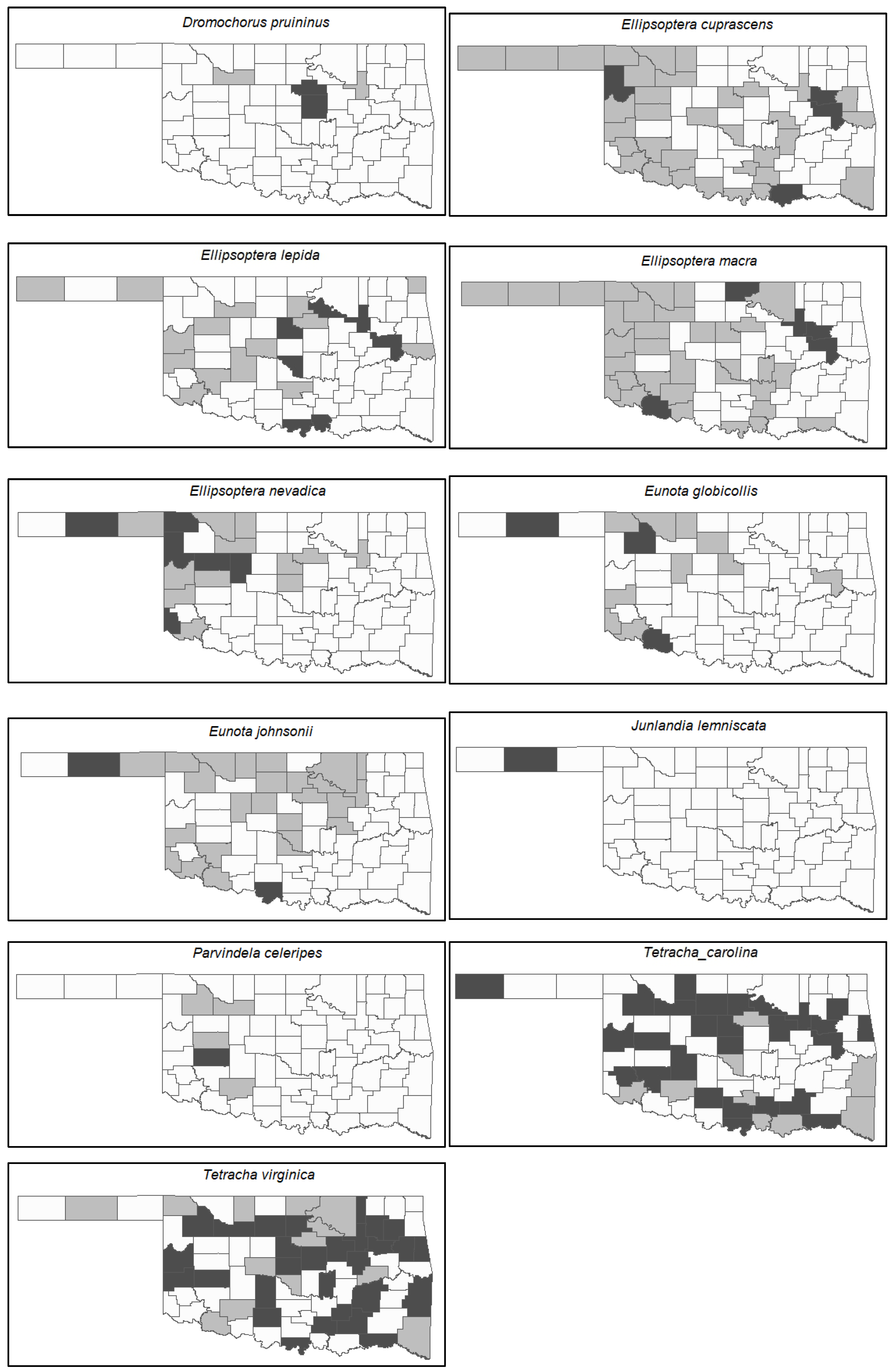

- Ellipsoptera cuprascens (LeConte, 1852) (4, 38)

- New records: Bryan, Ellis, Muskogee, Wagoner

- Notes: This species is commonly found along rivers, large lakes, and occasionally salt flats, though it tends to be most abundant on large sandbars. It is a good disperser and can be collected at lights that are over 10 km away from appropriate habitat. Drew and Cleave [16] reported records of E. cuprascens from Mayes, Noble, and Pottawatomie Counties, but these are currently excluded as it is unknown whether these referred to E. cuprascens or E. macra.

- Ellipsoptera lepida (Dejean, 1831) (7, 22)

- New records: Cleveland, Logan, Love, Marshall, Muskogee, Pawnee, Tulsa

- Notes: Ellipsoptera lepida is usually associated with dry, upland sandy habitats, although it can occasionally be collected along rivers where sandbars are sufficiently high enough to avoid regular flooding. Like E. cuprascens, it is commonly attracted to lights at night, and so occurrence records may not be indicative of the presence of viable populations. Like Cicindela lengi, this species has likely been lost from sites in the Panhandle, where an increase in vegetation cover and a decrease in river flow have simultaneously reduced available habitat and decreased the creation of new habitat.

- Ellipsoptera macra (LeConte, 1856) (5, 38)

- New records: Kay, Muskogee, Tillman, Tulsa, Wagoner

- Notes: This species is often found in the same habitats as E. cuprascens, with which it often cooccurs. E. cuprascens seems more tolerant of muddy substrates, while E. macra prefers sand. The subspecies distribution in Oklahoma is interesting, as populations in the northeast appear to be the nominate subspecies, while those in the southern and western parts of the state are assigned to E. m. fluviatilis (Vaurie, 1951). In our experience, specimens collected along the Arkansas River bear a closer resemblance to the nominate subspecies, but elsewhere this species shows the wider maculations and redder coloration associated with E. m. fluviatilis.

- Ellipsoptera nevadica (LeConte, 1875) (6, 18)

- New records: Blaine, Dewey, Ellis, Harmon, Harper, Texas

- Notes: This species is commonly found on open salt flats and along saline rivers, where it usually occurs near the edge of the water where the ground is saturated. It is commonly attracted to lights at night, where it can be observed in high numbers.

- Eunota johnsonii (Fitch, 1857) (2, 27)

- New records: Jefferson, Texas

- Notes: Eunota johnsonii is usually found on open salt flats, although it is also found along sandbars of some of the more saline rivers, such as the Red and Cimarron Rivers, much like Ellipsoptera nevadica. Most populations in Oklahoma are dominated by reddish individuals that match the surrounding clay, but an isolated population near Tulsa has a higher proportion of green and blue individuals.

- Eunota globicollis (Casey, 1913) (3, 13)

- New records: Texas, Tillman, WoodwardNotes: Like E. johnsonii, E. togata is found primarily on open salt flats but does not occur as regularly along rivers and does not go as far east as E. johnsonii. The population in Texas County occurs on an artificial salt flat, which was inadvertently formed when the Beaver River was dammed to create Optima Reservoir. As the river dried up, so did the lake, and the resulting salt flat was subsequently colonized by the usual guild of saline-associated species, E. togata, E. johnsonii, Ellipsoptera nevadica, and Cicindela fulgida. The creation of this habitat accounts for the novel Texas county records for all four species.

- Jundlandia lemniscata (LeConte, 1854) (one, one)

- New records: Texas

- Notes: This species has been photographed at one site near Fulton Creek and has been found in multiple years (2021, 2024) at Optima Lake. At both sites, it was associated with gravel. It is easily overlooked because of its small size and passing resemblance to ants, Pogonomyrmex spp.

- Parvindela celeripes (LeConte, 1846) (one, five)

- New records: Washita

- Notes: This small, flightless species is typically found amongst gypsum outcrops in Oklahoma (Figure 9). While it is uncommon and declining throughout much of its range (MacRae & Brown 2011), it can still be abundant where it occurs in Oklahoma.

- Tetracha carolina (Linnaeus, 1763) (27, 36)

- New records: Adair, Alfalfa, Atoka, Caddo, Carter, Choctaw, Cimarron, Creek, Custer, Garfield, Greer, Johnston, Kingfisher, Kiowa, Logan, Love, Major, Mayes, Muskogee, Noble, Oklahoma, Pawnee, Roger Mills, Stephens, Tulsa, Wagoner, Woodward

- Notes: This species is found in a variety of open habitats but is often found in high numbers near water. It can also be common around lights at night, where it feeds on the other insects that are attracted. This species is also frequently trapped in in-ground pools.

- Tetracha virginica (Linnaeus, 1767) (30, 43)

- New records: Adair, Atoka, Beckham, Cherokee, Choctaw, Coal, Creek, Garfield, Grady, Johnston, LeFlore, Lincoln, Logan, Love, Major, Mayes, Muskogee, Noble, Oklahoma, Okmulgee, Pittsburg, Roger Mills, Rogers, Seminole, Stephens, Tulsa, Wagoner, Washington, Washita, Woodward

- Notes: This species, like T. carolina, is found in a wide variety of open habitats, from lawns and parking lots to prairies. Unlike T. carolina, it is not associated with moist environments and can be found in xeric glades in the Ozark Mountains and in dry grasslands away from water.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OSEC | K.C. Emerson Entomology Museum, Oklahoma State University |

| SEMC | Snow Entomological Museum, University of Kansas |

| OMNH | Sam Nobel Museum of Natural History, University of Oklahoma |

Appendix A

References

- Duran, D.P.; Gough, H.M. Validation of tiger beetles as distinct family (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae), review and reclassification of tribal relationships. Syst. Entomol. 2020, 45, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knisley, C.B.; Gwiazdowski, R. Conservation strategies for protecting tiger beetles and their habitats in the United States: Studies with listed species (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Cicindelidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2021, 114.3, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosius, T.R.; Higley, L.G. Behavioral niche partitioning in a sympatric tiger beetle assemblage and implications for the endangered Salt Creek tiger beetle. PeerJ 2013, 1, e169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melius, D.A. Post-monsoonal Cicindela of the Laguna del Perro region of New Mexico. Cicindela 2009, 41, 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, T.D. Habitat preferences and seasonal abundances of eight sympatric species of tiger beetle, genus Cicindela (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae), in Bastrop State Park, Texas. Southwest. Nat. 1989, 34, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, D.P.; Laroche, R.A.; Roman, S.J.; Godwin, W.; Herrmann, D.P.; Bull, E.; Egan, S.P. Species delimitation, discovery and conservation in a tiger beetle species complex despite discordant genetic data. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, D.L.; Ghorpade, K. Geographical distribution and ecological history of tiger beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) of the Indian subcontinent. J. Biogeogr. 1989, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, H.L. Bionomics and Zoogeography of Tiger Beetles of Saline Habitats in the Central United States (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae). Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, T.D.; Quinlan, M.C.; Hadley, N.F. Preferred body temperature, metabolic physiology, and water balance of adult Cicindela longilabris: A comparison of populations from boreal habitats and climatic refugia. Physiol. Zool. 1992, 65, 226–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brust, M.L.; Hoback, W.W.; Skinner, K.F.; Knisley, C.B. Differential immersion survival by populations of Cicindela hirticollis (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2005, 98, 973–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knisley, C.B. Anthropogenic disturbances and rare tiger beetle habitats: Benefits, risks, and implications for conservation. Terr. Arthropod Rev. 2011, 4, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knisley, C.B.; Kippenhan, M.; Brzoska, D. Conservation status of United States tiger beetles. Terr. Arthropod Rev. 2014, 7, 93–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, A.J.; Baltierra, R.J.; Webster, R.; Hoback, W.W. New state records of three tiger beetle species in Oklahoma. Southwest. Entomol. 2024, 49, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, D.P.; Herrmann, D.P.; Roman, S.J.; Gwiazdowski, R.A.; Drummond, J.A.; Hood, G.R.; Egan, S.P. Cryptic diversity in the North American Dromochorus tiger beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Cicindelinae): A congruence-based method for species discovery. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2019, 186, 250–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, P.M.; Kondratieff, B.C. Natural history of the Colorado great sand dunes tiger beetle, Cicindela theatina Rotger. Trans. Am. Entomol. Soc. 2003, 333–360. [Google Scholar]

- Drew, W.A.; Van Cleave, H.W. The tiger beetles of Oklahoma (Cicindelidae). Proc. Okla. Acad. Sci. 1962, 101–122. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, J.P. Tiger beetles of Fort Sill, Comanche County, Oklahoma, with a new state record for Cicindela ocellata rectilatera Chaudoir. Cicindela 2004, 36, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Duran, D.P.; Laroche, R.A.; Gough, H.M.; Gwiazdowski, R.A.; Knisley, C.B.; Herrmann, D.P.; Roman, S.J.; Egan, S.P. Geographic life history differences predict genomic divergence better than mitochondrial barcodes or phenotype. Genes 2020, 11, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacRae, T.C.; Brown, C.R. Historical and contemporary occurrence of Cylindera (s. str.) celeripes (LeConte)(Coleoptera: Carabidae: Cicindelinae) and implications for its conservation. Coleopt. Bull. 2011, 65, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, A.J.; Brust, M.L.; Royer, T.A.; Mulder, P.; Hoback, W.W. New state and county records of short-horned grasshoppers (Orthoptera: Acrididae and Romaleidae) in Oklahoma. Southwest. Entomol. 2022, 47, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, A.J.; Brust, M.L.; Watson, J. Distribution update for Wisconsin tiger beetles with 61 county records. Cicindela 2020, 52, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, T.W.; Johnson, P.G. First record of Cicindelidia punctulata in California. Cicindela 2019, 51, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.D.; Patten, M.A. Dragonflies at a Biogeographical Crossroads: The Odonata of Oklahoma and Complexities Beyond its Borders; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, J.P. New county records for Cicindelidae in South Carolina. Cicindela 2002, 34, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, J.P. More new county records for Cicindelidae in South Carolina. Cicindela 2004, 36, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Brust, M.L.; Hoback, W.W.; Spomer, S.M.; Allgeier, W.J.; Nabity, P.D. New county records for Nebraska tiger beetle. Cicindela 2005, 37, 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- Brust, M.L. New tiger beetle observation and county records for Nebraska and a new state record for Cicindela tenuisignata LeConete. Cicindela 2006, 38, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Oklahoma Department of Wildlife and Conservation. Oklahoma Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy: A Strategic Conservation Plan for Oklahoma’s Rare and Declining Wildlife. Report Published in 2016. Available online: https://www.wildlifedepartment.com/sites/default/files/2021-11/Oklahoma%20Comprehensive%20Wildlife%20Conservation%20Strategy.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Costa, L.L.; Arueira, V.F.; de Almeida Caetano, J.P.; do Nascimento, A.B.; e Ribeiro, B.T.; Sartori, É.; da Silva Valle, H.S.; do Nascimento, L.S.; Rangel, D.F.; Bulhões, E.; et al. Testing classical hypotheses on sandy beach ecology with a “goldilocks” indicator species: Study case with tiger beetles (Insecta: Cicindelidae). Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2025, 314, 109151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, D.L.; Knisley, C.B.; Duran, D.P.; Kazilek, C.J. A Field Guide to the Tiger Beetles of the United States and Canada: Identification, Natural History, and Distribution of the Cicindelids, 2nd ed.; Oxford Univ. Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Duran, D.P.; Gough, H.M. A new genus of tiger beetle (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) from the Nearctic and Neotropical realms. Zootaxa 2022, 5175, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, R.A.; Duran, D.P.; Lee, C.T.A.; Godwin, W.; Roman, S.J.; Herrmann, D.P.; Egan, S.P. A genomic test of subspecies in the Eunota togata species group (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae): Morphology masks evolutionary relationships and taxonomy. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2023, 189, 107937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knisley, C.B.; Fenster, M.S. Apparent extinction of the tiger beetle, Cicindela hirticollis abrupta (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Cicindelinae). Coleopt. Bull. 2005, 59, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritsky, G.; Gallagher, N.T.; Smith, J.; Watkins, A. The Decline of Cicindela hirticollis Say in Ohio (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae). Ohio Biol. Surv. Notes 1999, 2, 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mawdsley, J.R. Geographic variation in US populations of the tiger beetle Cicindela obsoleta Say (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae). Insecta Mundi 2009, 94, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Harman, A.J.; Hoback, W.W. Updated List of Oklahoma Tiger Beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) with Notes on Their Distribution and Conservation Status. Diversity 2025, 17, 463. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17070463

Harman AJ, Hoback WW. Updated List of Oklahoma Tiger Beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) with Notes on Their Distribution and Conservation Status. Diversity. 2025; 17(7):463. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17070463

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarman, Alexander J., and W. Wyatt Hoback. 2025. "Updated List of Oklahoma Tiger Beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) with Notes on Their Distribution and Conservation Status" Diversity 17, no. 7: 463. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17070463

APA StyleHarman, A. J., & Hoback, W. W. (2025). Updated List of Oklahoma Tiger Beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) with Notes on Their Distribution and Conservation Status. Diversity, 17(7), 463. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17070463