3. Paleontological Description

Actinopterygii Cope, 1871

Peltopleuriformes Gardiner, 1967

Thoracopteridae Griffith, 1977

Emended diagnosis. (* for apomorphic character inside the family): Small to medium-sized fishes. Skull roof bones randomly fused, usually with broad paired frontals, but large parieto-dermopterotic sometimes fused together; no distinct parietals. Nasals separated by a large convex rostral. Supraorbital single or few in number. One suborbital. Opercular series with large opercle, smaller subopercle, several branchiostegal rays*, lateral and median gulars. Vertical, very narrow preopercle abutting the rear edge of the maxilla with the infraorbital process*. Maxilla extending beyond posterior border of orbit and with large postero-ventral plate. Mandible with very low coronoid process. Spiracular bones present. Large otoliths present*. Sensory canal system reduced. Posterior preural neural spines expanded substantially longitudinally*. Body totally or partially scaled, or naked. Tail semiheterocercal, with more than ten epaxial rays*. Caudal fin deeply forked, with lower lobe much larger than upper**. Pectoral and pelvic fins very large and elongated (over 30% of s.l.)*. Anal and dorsal fins well posteriorly inserted; lepidotrichia reduced in length in the dorsal fin*. Anal fin sexually dimorphic.

Remarks. Griffith [

3] considered

Thoracopterus as belonging to the Luganoiformes (together with his “

Habroichthys” gregarius Griffith, 1977 [

3]). Lehman [

4] previously noted that

Thoracopterus has nothing to do with

Luganoia and

Besania and set

Thoracopterus close to Perleidiformes. Tintori and Sassi [

5] considered

Thoracopterus related to

Peltopleurus (thus belonging to Peltopleuriformes) rather than to

Perleidus (Perleidiformes). Since then, these flying fishes have been included in this order.

Shen and Arratia [

40] erected the superfamily Thoracopteridea, as well as a few new generic taxa for the Thoracopteridae, claiming that

Thoracopterus is not “monophyletic,” but without giving a clear explanation. The author does not consider their analysis to be valid, or their taxonomic conclusion, because the Thoracopteridea diagnosis shows several inconsistencies and mistakes, as shown below (in italics) where the characteristics they used in the superfamily diagnosis are discussed, and the matrix by Shen and Arratia [

40] used for the phylogenetic analysis is not at all precise with regard to many characteristics (see below).

“Small (c. 60 mm) to medium-sized (c. 190 mm) fishes”. Most Triassic actinopterygian fishes are within this range, apart from the large predatory taxa such as

Saurichthys and

Birgeria. It may be better to retain it inside peltopleuriforms so that this size range may have real meaning, although

Wushaichthys is out of this range, as in Shen and Arratia [

40], it is said to be a maximum of 57 mm in total length, with most specimens being much shorter (pers. obs.). Additionally, the length of

Peripeltopleurus is, on average, below the lower boundary of 60 mm [

41], so the given range seems to be correct for Thoracopteridae but not for the other taxa considered in the new superfamily.

“Frontal bones are unfused; frontal bones are broad and laterally expanded at orbital level*”. Frontals are unfused in most actinopterygian fishes, as fusion among skull roof bones is quite a rare event, and usually it is erratic even inside the same species, as for

Thoracopterus martinisi, where the skull roof bone can be totally fused and there is also a narrowing at the orbital level [

5], or for

T. “

niederristi” from Polzberg [

3] (pers. obs. 2025), which is actually a new species, different from the one from Raibl (Tintori and Conedera, submitted). In Shen and Arratia [

40] (Figure 9A,B), the frontals in

Wushaichthys appear as if they can fuse to each other. The same is observed in

Peripeltopleurus [

40] (Figures 154B and 155A). Similar variability in fusion of the skull roof bones is shown in several peltopleuriforms, such as

Habroichthys [

10,

33],

P. tyrannos [

42], and

P. nitidus [

43], or in advanced neopterygians, such as

Prohalecites [

44]. Thus, this appears to be a general characteristic of actinopterygians, but not for this superfamily or for Peltopleuriformes, where frontal fusion is quite common.

“Parietal bone and dermopterotic are fused into a large parieto-dermopterotic”. See above.

“No postrostral bone in skull roof. Nasal bones are separated medially by a large rostral bone”. The postrostral is present in very few basal actinopterygians, and apparently only in

Colobodus among “subholosteans” [

45,

46]. No other peltopleuriform or perleidiform has this bone, and in all peltopleuriforms, the large rostral totally separates the nasal bones [

12,

47,

48,

49], while in perleidiforms, the nasals are usually in contact shortly after the rostral [

11,

49,

50]. It must also be noted that Shen and Arratia [

40] accepted the restorations of

T. “

niederristi” and

T. telleri made by Griffith [

3] and Lehman [

4], where the nasals meet in front of the frontals, clearly in contrast with this diagnostic character. However, Tintori and Sassi [

5] reported that the restorations were wrong (see also Tintori and Conedera, submitted). However, this is a general characteristic of Peltopleuriformes.

“Posttemporal contacts extrascapular anterolaterally and separates this bone from contacting its counterpart*”. This is not the case for

T.

magnificus and

T.

martinisi [

5], whereas in

T. telleri, the area is not known. In

T. “

niederristi” from Polzberg, both Griffith [

3] and Lehman [

4] consider the two bones medial to the lateral extrascapular as “median extrascapular”. In

Wushaichthys, Shen and Arratia [

40] (Figure 10A), the posttemporal is just posterior to the extrascapular. Thus, this characteristic, even if considered synapomorphic for the superfamily, does not appear to be present in almost all the taxa.

“Spiracular bone(s) present”. This is a very general observation in most actinopterygians.

“Skull roof sensory canal system short, simple and discontinuous, with a few small sensory pores opening directly on the surface of the canal”. This is also the case in many other peltopleuriforms and perleidiforms, for instance,

Peltopleurus and

Habroichthys [

10,

33,

43,

48,

51].

“Elongate maxilla extending beyond the posterior margin of the orbit”. All other Peltopleuriformes (and Perleidiformes) show this characteristic. This is the standard state in all non-neopterygian actinopterygians, and also some advanced Triassic neopterygians, such as most Pholidophoridae [

14,

17] and the Panxianichthyformes halecomorphs show this character, so the meaning of this characteristic for the superfamily can be questioned; thus, it is not clear what the significance of this characteristic is for the superfamily.

“Enlarged antorbital, nearly equal to or deeper than the nasal bone”. Not in all species.

“One or a few supraorbital bones. Few to several suborbitals present”. These are common states for most actinopterygian fishes. Regarding peltopleuriforms, in all

Thoracopterus species, these bones are not usually recorded, or for suborbitals, there is a single large bone [

5,

15], as for

Peltopleurus specimens [

15,

48]!

“Lower jaw with low coronoid process or process absent”. Again, this is a general non-neopterygian characteristic.

“Surangular bone commonly missing”. Alternatively, you cannot clearly see this region in such small fishes with no coronoid process.

“Opercle more than 2.5 times as large as the subopercle”. Many other peltopleuriforms, such as

Habroichthys, a few

Peltopleurus, and

Nannolepis, show a very small subopercle [

3,

10,

33].

“Preopercle narrow and a deep rectangular bone, vertically oriented *. Preopercle suturing with rear edge of the maxilla throughout the maxillary process*. Preopercular sensory canal simple, with one short branch extending into the maxillary process. Suspensorium vertically oriented”. These are common characteristics in almost all Peltopleuriformes, with only

Habroichthys being somewhat different in having a very short suture with the maxilla [

33]; thus, these characteristics are Peltopleuriformes synapomorphies.

“Interopercle absent”. Again, this is true for all non-neopterygian actinopterygians and thus also for all Peltopleuriformes and Perleidiformes.

“Median and lateral gulars present in most specimens”. A diagnostic characteristic should be present in (almost) all the considered taxa, not specimens (see below for several other characteristics where Shen and Arratia [

40] used “most genera” or “generally”). Using “specimens” makes things unclear. Furthermore, gulars are present in almost all non-neopterygian actinopterygians, although they are usually not recorded in many miniature peltopleuriforms but are present in

Perleidus altolepis (Deecke, 1889) [

49,

52] and

Colobodus [

46].

“Enlarged pectoral fins in most genera”. The term “enlarged” can be interpreted in many ways; for instance, in

Wushaichthys exquisitus, they are in the same proportion to standard length as in

Peltopleurus nuptialis Lombardo, 1999 [

40,

48], as in almost all other Peltopleuriformes. However, they are much shorter than in “true” flying fishes (

Thoracopterus spp. or Thoracopteridae), where pectorals should be at least around 30% of the fish’s standard length [

9,

15].

“Pelvic fin well developed in most genera”. See above.

“Fringing fulcra on leading margin of paired fins generally absent. Fringing fulcra on leading margin of the dorsal and anal fins absent”. This characteristic appears to be very widespread among peltopleuriforms.

Peltopleurus shows only very small fringing fulcra on both margins of the caudal fin [

47,

48], as for

W. exquisitus [

40].

Altisolepis lacks fringing fulcra in all fins [

12], as is also the case for

Habroichthys [

10,

33] and

Nannolepis [

3] (pers. obs., 2025). Thus, again, this is a Peltopleuriformes characteristic and is also shown in a few Perleidiformes, such as

Dipteronotus [

47].

“Dorsal and anal fins generally posteriorly inserted, closer to caudal fin than the midpoint of body length”. As in many other Triassic fishes, and also in most Peltopleuriformes.

“Dorsal and anal fin rays reduced in length”. As in many other Triassic fishes.

“Caudal fin forked, with its hypaxial lobe longer than the epaxial lobe*. Hypaxial lobe of caudal fin broader than epaxial lobe”. The actual ratio between the two lobes is quite different in Thoracopterus with respect to Wushaichthys or Peripeltopleurus.

“Scales (when present) of the main horizontal row, along the lateral line, much deeper than scales above and below the lateral-line scales”. All scaled “subholosteans” (Peltopleuriformes, Perleidiformes, Pholidopleuriformes) share this characteristic. A few Middle Triassic neopterygian fishes, such as

Placopleurus, show a high flank scale row [

53] (Conedera et al., submitted).

Genus Thoracopterus Bronn, 1858

Type species: Thoracopterus niederristi Bronn, 1858.

Other species: T. telleri (Abel, 1906), T. magnificus Tintori and Sassi, 1987, T. martinisi Tintori and Sassi, 1992, T. wushaensis Tintori et al., 2012, and T. sp. n. Tintori and Conedera, submitted.

Diagnosis: As for the family because it includes only one genus.

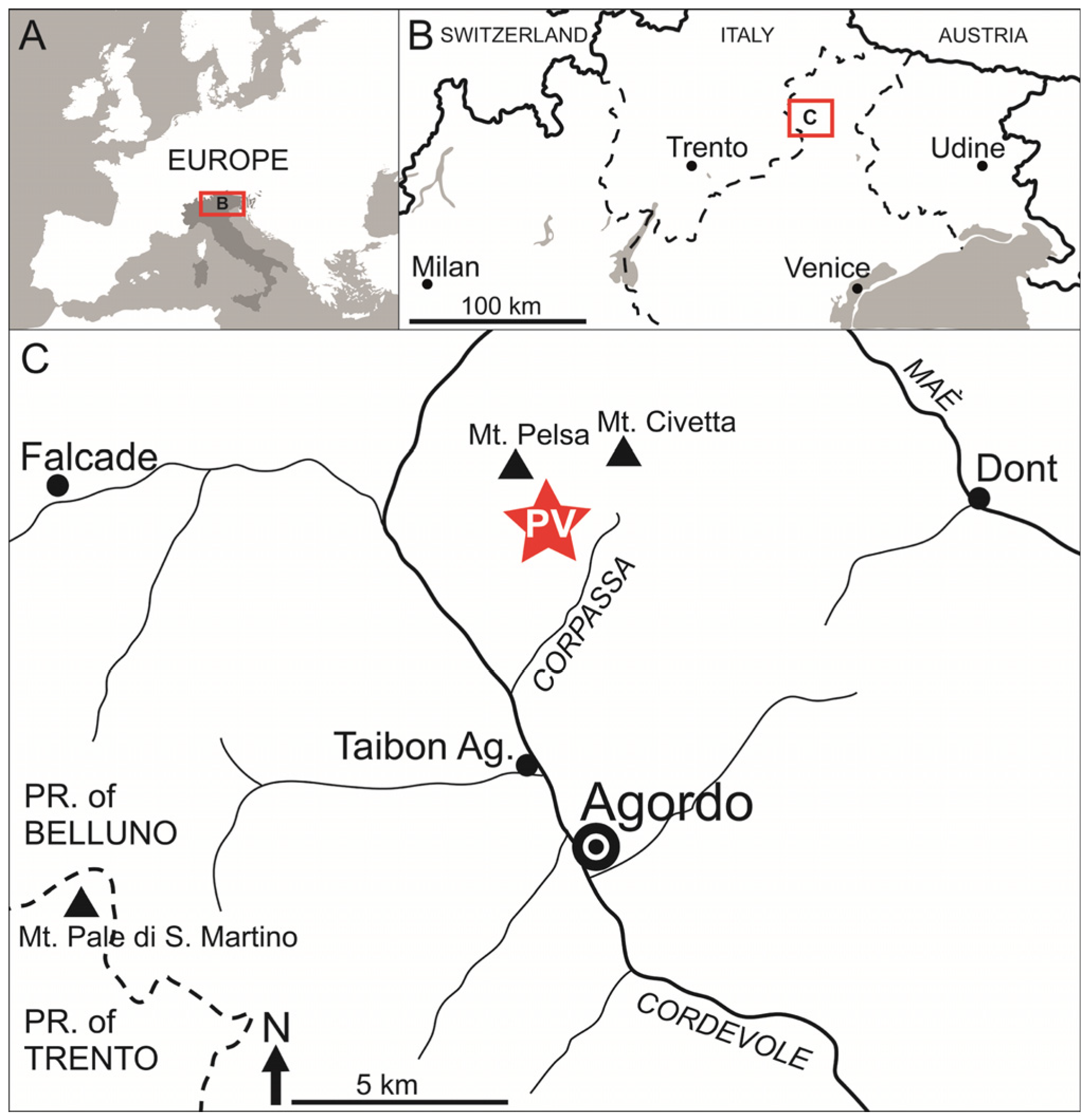

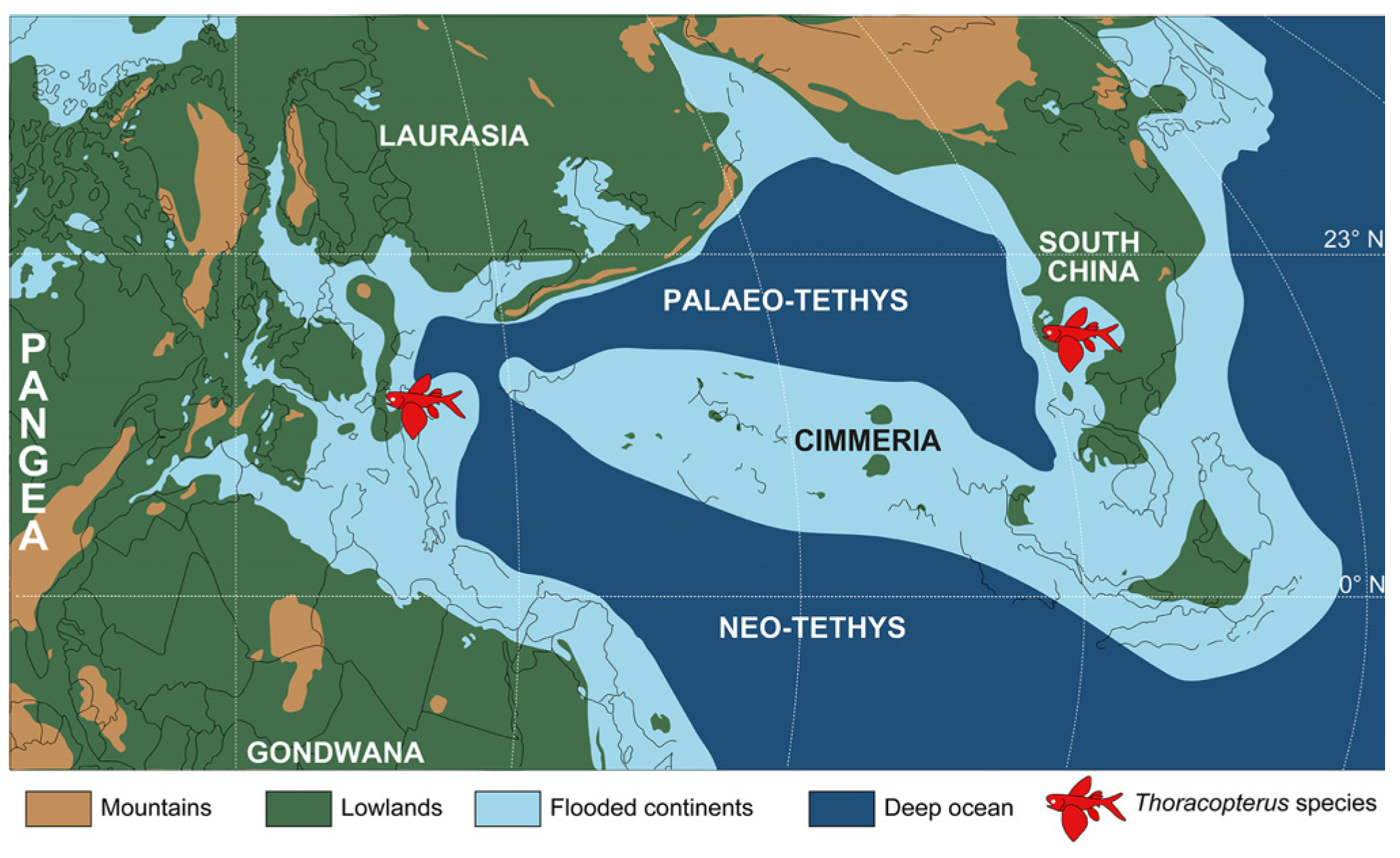

Age and geographical distributions: Late Ladinian (Middle Triassic) of the Western Tethys (Dolomites, Belluno Province, northeastern Italy) and Eastern Tethys (Xingyi area, Guizhou Province, southwestern China) to the Late Triassic of the Western Tethys (early Carnian of Austria and early Carnian to Norian of northern Italy).

Remarks. Since the original description of

T. wushaensis by Tintori et al. [

15], a few authors have dealt with this species, the other Triassic flying fishes, and the related peltopleuriforms, starting from Xu et al. [

54] with the description of other specimens, not collected in situ, under the name

Potanichthys xingyiensis, down to Shen and Arratia [

40]. However, as will be discussed in the following paragraphs, the anatomical descriptions, the characteristics identified, the comparison with other taxa, and the related phylogenetic analyses are herein considered too scant to support their conclusions from a nomenclatural point of view. Several of these problematic aspects have already been pointed out in Tintori [

55]. For their analysis, Xu et al. [

56] used 23 taxa with 80 characteristics, while Shen and Arratia [

40] used 137 characteristics from 54 taxa. A random check was performed on Xu et al.’s [

56] matrix on a few taxa the author is familiar with (

Habroichthys,

Venusichthys,

Peltopleurus-

Peripeltopleurus-

Wushaichthys), and the results are shown further below. The high number of wrongly coded characters, other than the several missing ones, together with other problematic assumptions, leads the author to discard this analysis and those following as an upgrade of the original one. A check of the most recent analysis [

40] also unveils problems in the coding of the Thoracopteridae species and, for

T. niederristi (the new species from Polzberg, so the type species is not considered), shows 40 unknown characteristics, which are reduced to 39 after checking and changing 27 wrongly coded ones; for

T. wushaensis, 23 were unknown, now 26 with 17 wrongly coded ones; for

T. telleri, 64 were unknown, now 57 with 29 wrongly coded ones; for

T. magnificus, 53 were unknown, now 49 with 9 wrongly coded ones; and for

T. martinisi, 49 were unknown, now 44 with 17 wrongly coded ones. All this makes the statistical analysis very poor and not suitable to be trusted.

The geographic and stratigraphic positions of the Chinese material described by Xu et al. [

54], Xu et al. [

56], Xu and Zhao [

53,

57], and Shen and Arratia [

40] are imprecise, as Tintori [

55] already pointed out. None of those papers provide a studied section, record, or number of beds yielding the studied specimens. Moreover, the photographs of the outcrops only show some bedded dark limestone, sometimes moss-covered [

40,

57], that could belong to any of the several bedded limestone units in southwestern China (or elsewhere), or they show one of the authors [

57] without a hammer beside a pile of slabs, a typical remnant of excavations by locals. We must also keep in mind that the only scientific excavations in the Xingyi area have been those in Nimaigu (Wusha District, Xingyi City) and in Dingxiao, carried out by the international team led by PKU paleontologists, from which all the specimens are recorded with the bed number, such as the case of

T. wushaensis [

14,

15]. The Dingxiao locality is very close to the site from which the first fossils of the Xingyi Fauna were described [

19], while the large Nimaigu excavation is about 50 km to the west. This detailed stratigraphic position is very important in highly variable groups such as Peltopleuriformes, as different species can very often be recorded in a very short stratigraphical interval of only a few beds, as the author could observe for

Peltopleurus in the Kalkschieferzone from Monte San Giorgio,

Habroichthys [

33], or also for “

Wushaichthys” in the Nimaigu excavation itself (pers. obs.). In the latter sequence, peltopleurids other than

H. orientalis are quite common all along the fossiliferous level, which is subdivided into two major fossil assemblages, each one characterized by a very different array of taxa [

14]. Although peltopleurids seem to be more common in the Upper Assemblage, a few specimens have also been found in bed 35, together with the very common

H. orientalis, and below (pers. obs. during 2012–2013 fieldwork, when the author spent more than two months there in the bed-by-bed excavation). The type material of

T. wushaensis is from this scientific excavation [

15] and not “endemic to the village of Xiemi, Wusha district, City of Xingyi” [

40], as Xu et al. [

54] described

Potanichthys xingyiensis. As already pointed out by Tintori [

55], around Xiemi Village, no official excavations have been carried out, so the actual source of the Xu et al. [

54] material is still in question. However, as

P. xingyiensis is a junior synonym of

T. wushaensis, as already stated in Tintori et al. [

20] and Tintori [

55] and accepted by Shen and Arratia [

40], this species cannot be endemic to Xiemi, but at present is to be considered part of the Upper Assemblage of the Xingyi Fauna [

15] and is probably known from a few different localities exploited by local fossil dealers, rather than from the Nimaigu type site. Shen and Arratia [

40] used the generic name “

Potanichthys” for the species

Thoracopterus wushaensis. However, as “

Potanichthys xingyiensis” is a synonym of

T. wushaensis, the use of the generic name should also be avoided, but this is unimportant, as the author does not consider the analysis by Shen and Arratia [

40] to be valid on the basis of several critical problems shown herein. It is also clear that the stratigraphy is not a strong argument for Shen and Arratia [

40], as they wrote that

Wushaichthys (which comes from the same stratigraphic unit as

T. wushaensis, although possibly a few meters below in the late Ladinian) is one of the oldest representatives of Thoracopteridea, but

Peripeltopleurus from the Besano Formation in Monte San Giorgio is from around the Anisian/Ladinian boundary, which is at least 2 Myr older! Thus, their chapter about “Evolutionary changes of fins” [

40] (p. 22) is not so sound.

None of the authors involved in those papers [

40,

53,

54,

56,

57] made a direct examination of European thoracopterid material held in Vienna, mostly housed at the Natural History Museum (the new species from Polzberg, as well as other specimens of

T. telleri) or in the former Geological Survey, now GeoSphere (original material of the type species

T. niederristi from Raibl/Cave del Predil,

T. telleri holotype), in Bergamo and Milan (

T. magnificus, original material and unpublished one), and in Udine (

T. martinisi original material and unpublished one). Although

T. telleri and

T. “

niederristi” from Polzberg have been redescribed by Griffith [

3] and Lehman [

4], their morphological descriptions were doubtful in several important aspects, as already pointed out by Tintori and Sassi [

5]. This uncertainty is mostly due to the poor preservation of several specimens, especially the much rarer

T. telleri [

3,

6] (pers. obs., 2013, 2025), in which the skeletal elements are usually not easily identifiable. Consequently, even Shen and Arratia [

40] provided only very scant information and did not describe the holotype or any other specimen showing the skull. This explains why, in their analysis of 137 characteristics, a total of 86 are missing or wrongly coded. To further show how problematic the anatomical interpretation of this species is, Shen and Arratia [

40] (Figure 6B) are clearly wrong in identifying as a “pelvic fin” (bottom left of the slab) the scattered hypaxial lobe of the caudal fin, while the other pelvic fin, probably the left if we consider the specimen as viewed from the ventral side, is partially visible just above the right one, thus in anatomical position, across the slab fracture (this is even more clearly visible in its counterpart NHMW 2007z0170/0206 (pers. obs., 2025)). The structures interpreted as “chordacentra” [

40] (Figure 6C) are also very doubtful, as in no other specimen are they visible when the vertebral column is preserved, and in this same specimen, scarce traces of the vertebral column are present only between the pectorals, but no chordacentra can be recorded. However, in their analysis, Shen and Arratia [

40] considered vertebral centra (autocentra or chordacentra, characteristic 95) as missing in

T. telleri. Griffith [

3] (Figure 7C) interpreted them as a “vestigial scale row” and, mostly owing to their shape and the presence of ganoine tubercles (pers. obs. on the counterpart, 2013, 2025), the author agrees with this interpretation. On the other hand, Shen and Arratia [

40] (p. 9) themselves underlined that “the anatomical information on thoracopterids is incomplete due to poor preservation of the specimens”; thus, working from pictures does not seem to be the best way to improve their knowledge.

We must also keep in mind that both Griffith [

3] and Lehman [

4] did not check the topotypical material of

T.

niederristi, but they just trusted Abel [

6]. In fact, it seems that there are a few differences between the Raibl topotypical

T. niederristi material and the Polzberg one described by Griffith [

3], Lehman [

4], and Shen and Arratia [

40], so the author assumes that they belong to two different species (pers. obs., 2025), leading to the erection of a new species (Tintori and Conedera, submitted). Thus, the

T. niederristi in the recent analysis [

40,

53,

54,

56] is actually a different species (Tintori and Conedera, submitted) and not the type species of the genus

Thoracopterus. This is also supported by the fact that no species are common between the two fish assemblages (Raibl and Polzberg), which are actually quite different from each other (pers. obs., 2013, 2025) and are also of different ages (Tintori and Conedera, submitted). Shen and Arratia [

40] (Figure 6A) show only a picture of a Polzberg specimen of T. “niederristi”, but their “dorsal fin” is actually the distal part of the right pectoral fin (pers. obs., 2025). Furthermore, all the references in the figures are only related to the fins without any details on the other characteristics used in the analysis, casting further doubt on their coding.

The Italian Norian species, despite being described more recently, lack the detailed description needed to code the 137 characters used by Shen and Arratia [

40], and they probably need to be redescribed using sound phylogenetic analysis, which is not the aim of the present paper. We must also keep in mind that most other peltopleurids are miniature fishes, 20–30 mm long, totally flattened, so it is almost impossible to check all the characteristics that are mostly related to neopterygians or teleosts. The author must finally point out that the major shared derived characteristic of the “subholosteans” (mainly Peltopleuriformes and Perleidiformes) is not present in all the considered analyses, i.e., the hemiheterocercal caudal fin with epaxial rays [

49], which is not recorded in any true neopterygian. Xu and Zhao [

43] describing

P. nitidus, used “almost homocercal”, as did Shen and Arratia [

40], which is not clear in its meaning, other than that the tails are “almost symmetrical”, although the terminology heterocercal, abbreviated heterocercal = hemihomocercal, homocercal, or hemiheterocercal, is based on the relationships between the internal structure and the rays. Perhaps “almost homocercal” could be used for advanced non-teleost neopterygians, such as

Marcopoloichthys or

Placopleurus, where the dorsal body lobe is extremely reduced to just a couple of scales (urodermals) [

21] (Conedera et al., submitted). Without considering this synapomorphic character shared by at least Peltopleuriformes, Perleidiformes, and Pholidopleuriformes, the basis of the analysis appears to be not so sound. Additionally, the enlarged neural spines in the caudal region of

T. magnificus,

T. wushaensis, and

T. martinisi, which are considered a synapomorphic characteristic of all thoracopterids, being strongly related to the flying capability [

5,

15], are not considered at all.

For Norian

Thoracopterus species, the age is wrongly stated by Shen and Arratia [

40], as

T. magnificus is said to be of “Middle Triassic” age, while it is from Norian (Late Triassic) sites of the Bergamo province, as well as from Seefeld (Austria) and Giffoni (Naples), not just from Endenna-Zogno.

T.

martinisi is from Norian sites too, but possibly somewhat older than those yielding

T.

magnificus, not simply “Late Triassic”, as stated by Shen and Arratia [

40] (the Late Triassic is 35 Myr long!), and comprises also the Carnian stage, which

T. niederristi,

T. telleri, and the new species from Polzberg are from. Regarding the size of the two Norian species, Shen and Arratia [

40] wrote that they are about 80 mm long. However,

T.

magnificus reaches at least 135 mm [

9], and

T. martinisi at least 200 mm (pers. obs. on undescribed material stored in Udine Museum).

For

Thoracopterus comparison, Lehman [

4] used the Early Triassic “

Perleidus” species from Madagascar, which has since been proven not to be a Perleidiformes [

11,

49,

58,

59]. Unfortunately, most other authors, and among them Xu et al. [

54], Xu et al. [

56], Xu and Zhao [

53], and Shen and Arratia [

40], followed Lehman [

4], not caring about the recent work on the type species of

Perleidus [

49,

59] or new species from southwestern China [

11]. Again, the presence of epaxial rays that differentiates the “subholosteans” from neopterygians is not considered (see, for instance, Xu et al. [

60]).

Venusichthys (Xu and Zhao, 2016) is considered a peltopleuriform based mainly on the very high flank scales, although Shen and Arratia [

40] put it outside Peltopleuriformes but still very close to

Habroichthys, always considered a peltopleuriform, although in a family of its own, Habroichthyidae, as in Gardiner [

61] (see also Conedera et al. [

33]). After checking material from both ends of the Tethys (the Luoping Fauna and different new Alpine sites), the author considers

Venusichthys to be a junior synonym of

Placopleurus Brough, 1939 [

62], due to their common unique scale ornamentation—very thin longitudinal striae on the anterior region, the one covered when in anatomical position that was not cited by Xu and Zhao [

53] but is present in Chinese specimens from the Luoping Fauna, as well as the peculiar preopercular and lower jaw structures (pers. obs.). Xu and Zhao [

53] wrote that their new genus is different from “the type species of

Placopleurus (

P. primus) from the late Ladinian (latest Middle Triassic) of Besano, Italy, as well as other known peltopleurids”. In fact, Brough [

62], when erecting

Placopleurus, used

P. primus as the type species based on a single very poorly preserved specimen, but ascribed a previously described species (

Pholidophorus besanensis Bassani, 1886 [

63]) to his new genus based on several specimens, which were not well preserved. The presence of the characteristic scale ornamentation is described for

P. besanensis, but it is also clearly visible on the imprint of some of the scales of the highly disarticulated holotype (and only specimen) of

P. primus (C. Lombardo, pers. com., 2004, Conedera et al., submitted). Furthermore, there is no typical peltopleuriform sexual dimorphism in

Placopleurus, as stated by Xu and Zhao [

53] (pers. obs. on both European and Chinese specimens), as there is no modification in the anal fin of the supposed males, and the caudal fin does not show any epaxial rays. In their phylogenetic analysis, for “

Venusichthys”, Xu and Zhao [

53] coded 80 characteristics, 22 of which were unknown or not available, and 12 were wrongly coded (1, 2, 31, 39, 44, 48, 52, 53, 54, 62, 65, and 70)! Additionally, the age of the Besano Formation is not late Ladinian (as stated by Xu and Zhao [

53]) but around the Anisian/Ladinian boundary. Thus, “

Venusichthys” being

Placopleurus is not a peltopleuriform at all, as it lacks, first of all, the hemiheterocercal tail with epaxial rays, and it is instead a non-teleost neopterygian (Conedera et al., submitted).

Regarding

Habroichthys, another iconic miniature peltopleurid fish from the Middle Triassic, the published analyses are, again, quite rough and unreliable. In the starting analysis by Xu and Zhao [

53], out of 80 characteristics, for

Habroichthys, 29 were unknown or NA, and 20 were clearly wrongly coded (1, 2, 18, 23, 30, 31, 33, 36, 44, 46, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 56, 65, 70, 79). This means that only 31 out of 80 characteristics (38%) have been correctly coded, most of them totally uninformative from a phylogenetic point of view, and 25% were wrongly coded! Shen and Arratia [

40] upgraded the analysis using 137 characters (please, again, keep in mind that

Habroichthys specimens are mostly less than 30 mm long and totally flattened, and the authors did not check any new specimens), but this did not change

Habroichthys’ position. It must also be pointed out that Xu and Zhao [

53] cited

H. orientalis (Su, 1959) as

Peltopleurus, not considering the main

Habroichthys derived characteristic, i.e., the last flank scale being enlarged and semicircular [

62]. Lin et al. [

10] and Tintori et al. [

64] moved this species to

Habroichthys because of this generic apomorphic character, which is not shown in any other peltopleuriforms but was not considered by Xu and Zhao [

53]. A new array of

Habroichthys specimens from various sites and ages is now under study [

33] (Tintori et al., submitted), but the average very small size and preservation quality will not vastly improve skull anatomy knowledge.

Other problems arise from the group of genera

Peltopleurus/Peripeltopleurus/Wushaichthys that can be considered very close to each other, as can be seen from the diagnoses [

41,

56] that are totally uninformative and do not explain the differences among the three genera. As for

Peltopleurus, in their analysis, Xu and Zhao [

53] did not consider the type species,

Peltopleurus splendens Kner, 1866 [

16], from the early Carnian of Raibl/Cave del Predil (Italy) but referred to published material of

P. rugosus Bürgin, 1992 [

41], from the Besano Formation (Monte San Giorgio), basing their observation on photographs or on the Chinese species

P. nitidus Xu and Ma, 2016, and

P. tyrannos Xu et al., 2018 [

40]. However, if these two latter species have been ascribed to

Peltopleurus, it is not clear why a new genus,

Wushaichthys, has been erected for the species

W.

exquisitus.

P. tyrannos, for instance, appears to be much closer to Perleidiformes than to peltopleurid in terms of scale pattern, preopercular shape, dentition, etc. However, regarding

Wushaichthys, it has been coded in Xu and Zhao [

53] with 22 unknown characteristics and 13 wrong ones (1, 15, 18, 22, 31, 44, 46, 48, 49, 54, 57,75, 79), while for

Peripeltopleurus, there are 22 unknown characteristics (but two are different from

Wushaichthys) and 11 wrong ones (1, 9, 15, 18, 31, 44, 46, 48, 55, 57, 79), with only 56% and 58% of the characteristics being correctly coded. In fact, the characteristics that separate

Wushaichthys and

Peripeltopleurus (clavicle and antorbital) are not easily visible in such small specimens, as has already been discussed herein. Finally, Shen and Arratia [

40] wrote that the

Wushaichthys specimens were from “near the village of Nimaigu”, although in Xu et al. [

56], it is reported as simply “Wusha”. What is certain is that the

Wushaichthys material of the type series and the new one described by Shen and Arratia [

40] are not from the official PKU excavations in Nimaigu. Thus, again, the real origin of the specimens is not clear, and, furthermore, it is not known if they are from a single site and/or from one bed or several different ones.

In conclusion, the author does not consider these analyses valid, following the above discussion, and the author considers Thoracopterus as a unique genus of the Thoracopteridae, comprising at least six species (T. “niederristi” from Polzberg is now considered a different species by Tintori and Conedera, submitted), considering four different genera for six species.

Thoracopterus wushaensis Tintori et al., 2012

2012 Thoracopterus wushaensis Tintori, Sun, Lombardo, Jiang, Ji, and Motani: p. 42, Figures 2–10.

2013 Potanichthys xingyiensis Xu, Zhao, Gao, and Wu: p. 2, Figure 1.

2014 Thoracopterus wushaensis Tintori et al.: p. 401, Figure 8

2015b Thoracopterus wushaensis Tintori: p. 1.

2024 Potanichthys wushaensis comb. nov.: Shen and Arratia: p. 9, Figure 6D

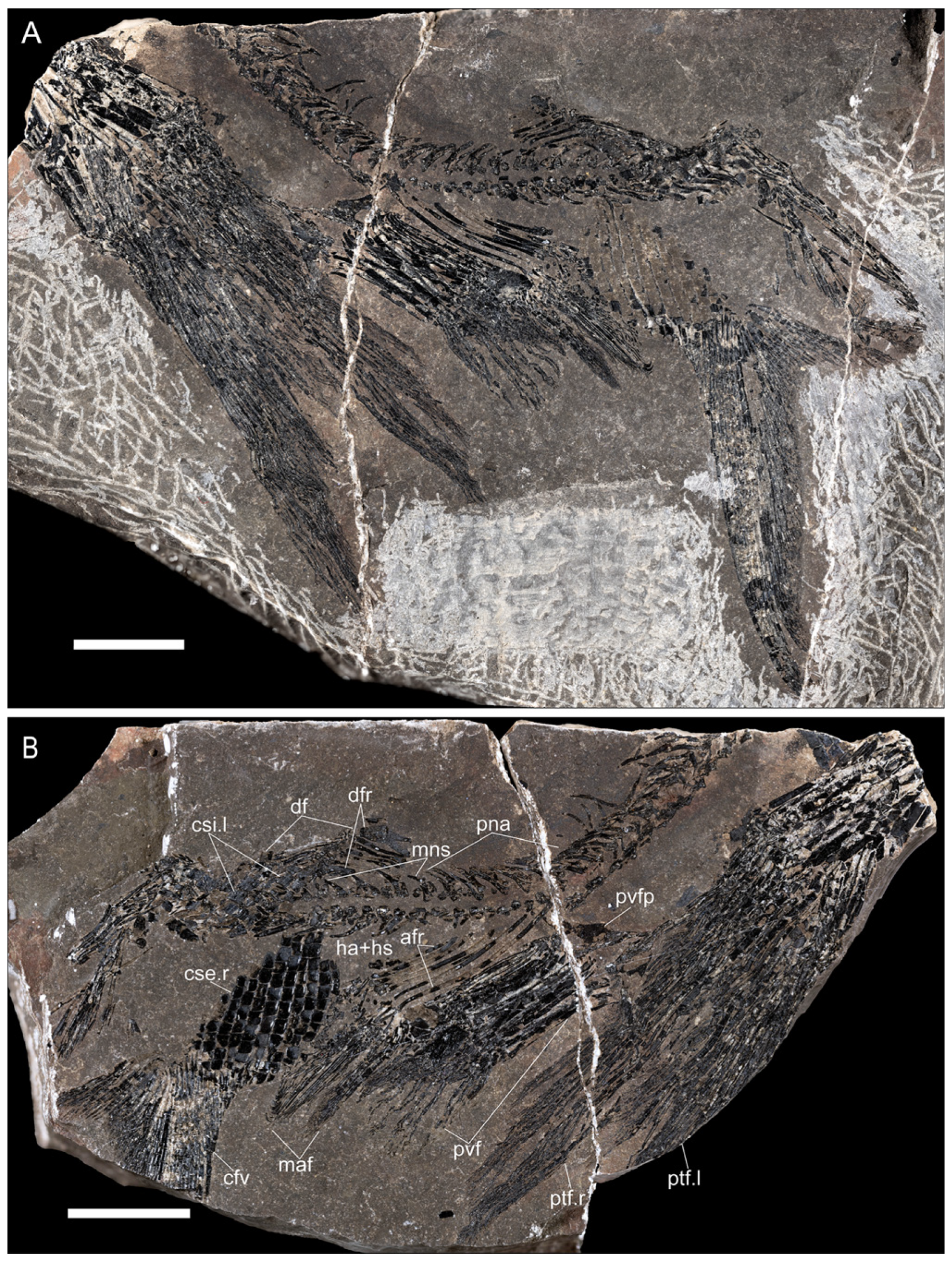

Material. A single specimen in part and counterpart, MGP-PD 33418a, b, stored at the Museo della Natura e dell’Uomo (Geo-Paleontological collections) of the University of Padua (

Figure 3).

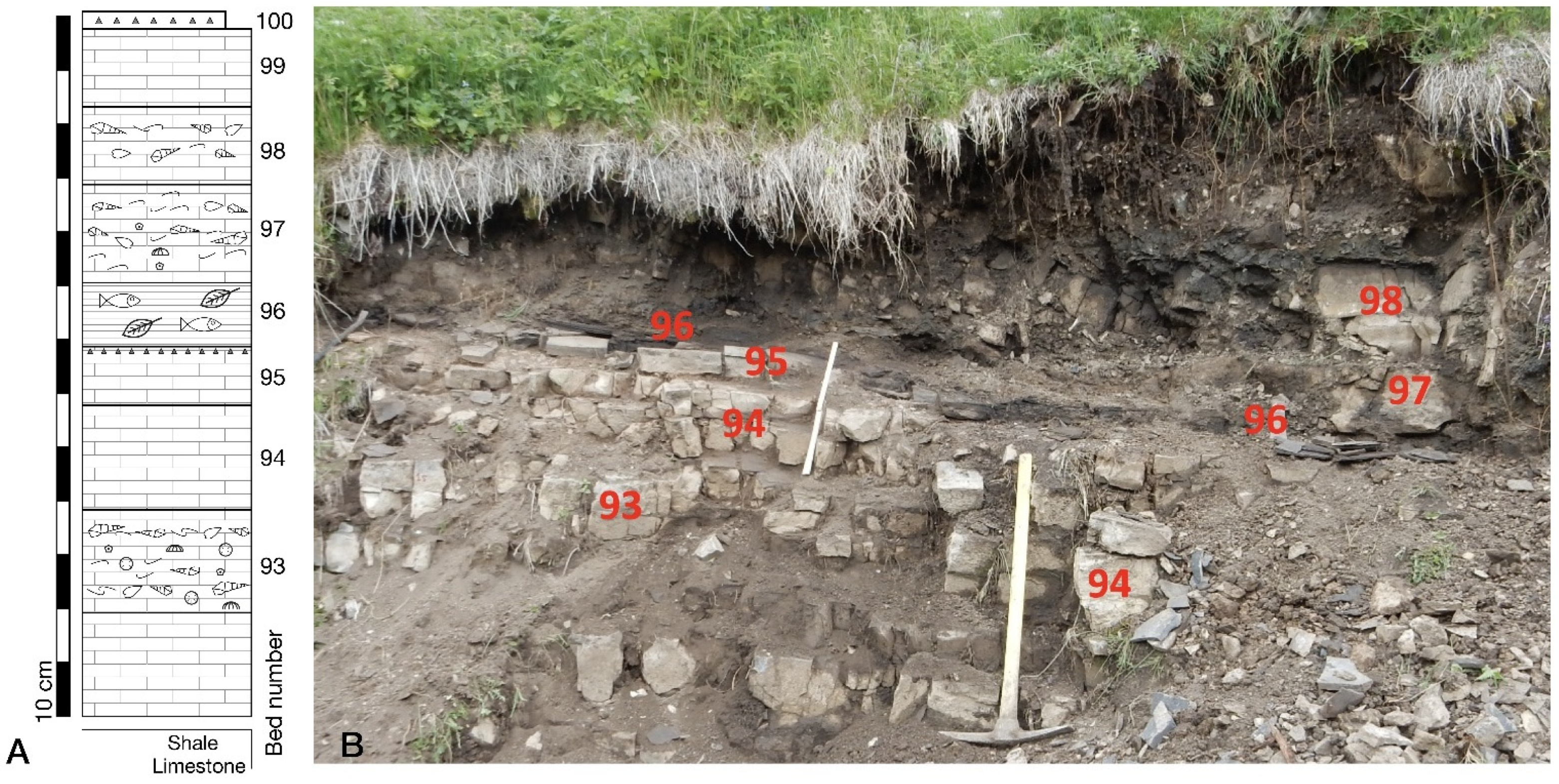

Stratigraphic and geographical distributions. The type locality is the scientific excavation near the village of Nimaigu (Wusha District, Xingyi City, Guizhou Province, China), Upper Vertebrate Horizon, lower part of the Zhuganpo Member of the Falang Formation, late Ladinian (Middle Triassic), although it is probably present in a larger area surrounding Wusha. The Pelsa/Vazzoler Fossil-Lagerstätte, Site A, bed 96 (“fish bed”), nearby Casera Pelsa (Taibon Agordino municipality, Agordino Dolomites, Belluno, Italy), Punta Santner Member of the Sciliar Formation (Longobardian, late Ladinian, Middle Triassic).

Description. The new Italian specimen is an incomplete one (part and partial counterpart) showing most of the body but lacking the skull and the anterior part of the vertebral column. The estimated standard length is around 110 mm, and the total length around 130 mm, well inside the range for the type series s.l. (87 mm to 117 mm).

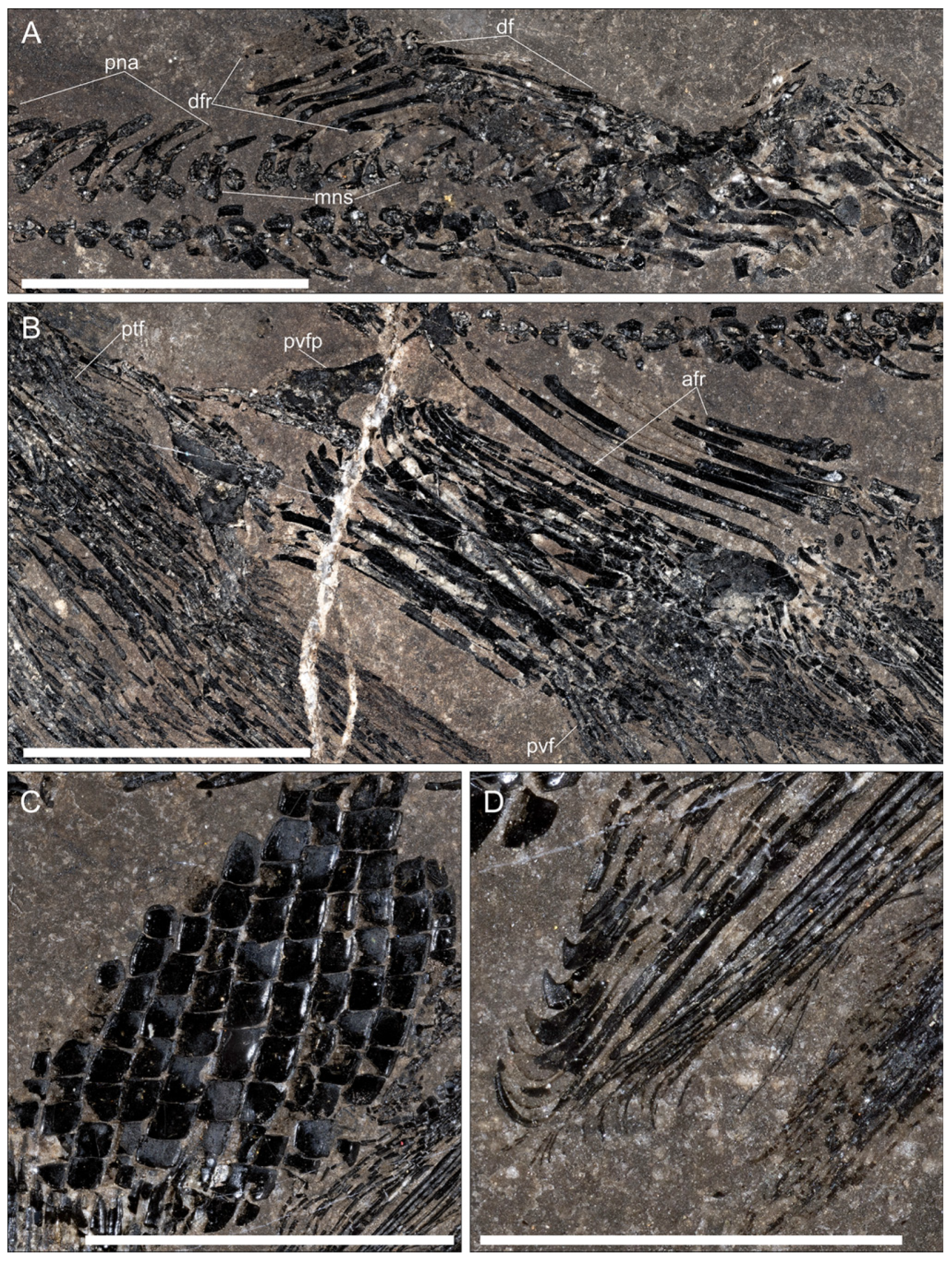

The vertebral column. The vertebral column of the specimen is visible, apart from the most anterior and the most posterior parts (

Figure 3B and

Figure 4A). In the thoracic region, the elongated paired neural arches show an anterior triangular process at the distal third. Supraneurals are present in the most anterior part (as in the type material [

15], probably down to halfway between the skull and the beginning of the dorsal fin, which is quite posteriorly inserted. Supraneurals are thin and much longer than the corresponding neural arches. Here, the haemal arches are strongly built and appear to make an almost continuous canal along the ventral side of the notochord to the first radial of the anal fin, which is very elongate (see below). Small bony splints are also present, and they have been interpreted as short ribs in the type material [

15]. In the region between the first anal radial and the beginning of the dorsal fin endoskeleton, the paired neural arches are shorter, and the haemal arches are smaller than the anteriormost ones, and still without a median spine that starts to appear in correspondence with the first dorsal fin radial. In this region, the vertebral column is clearly diplospondilous. Median neural spines are present from below the beginning of the dorsal fin [

15], although, unfortunately, the posterior part of the caudal region is not well preserved owing to the detachment of the caudal fin from the supporting endoskeleton.

Pectoral fins. Although not well preserved, at least 12 rays are visible, the anteriormost of which are very short, like in the type material. The surface of the proximal elements is ornamented with longitudinal ridges of ganoine. The preserved part, probably lacking only the very proximal end, is 55 mm long (

Figure 3).

Pelvic fins. The pelvic fins are much shorter than the pectorals, reaching 24–25 mm in length. Lepidotrichia, around 10 in number, are characterized by a very long proximal element, followed by a segmented region with two branches, the last one very distal (

Figure 3B and

Figure 4B). The first ray seems to be shorter than the maximum length of the fin and unbranched. Thin ganoine ornaments are present at least on the proximal elements. Very large triangular plates make up the endoskeleton of the fins.

Anal fin. The well-preserved anal fin shows the typical peltopleuriforms “male” structure [

48] (Figure 9A), wrongly interpreted as “female” in the paratype GMPKU-P-3071 by Tintori et al. [

15]. The endoskeleton is made of about 10 radials, probably subdivided into elongate axonosts and very small, rounded baseosts. The axonosts are very large and elongate, especially the first one, its proximal tip being close to the haemal arches. They are very forward inclined, as is also seen in the type material from China [

15]. Baseosts are round, their diameter corresponding to the distal width of the corresponding axonost. Externally, two large oval scales cover each side of the proximal region of the lepidotrichia of the anterior region. These scales are fully ornamented with low ganoin tubercles. As is typical in “male” peltopleuriforms, the external part of the fin is subdivided into three regions (

Figure 3B and

Figure 4D). The anterior part is made up of nine segmented rays that become somewhat thinner backwards. They are somewhat shorter than the median region rays, and they branch only very distally, at least twice, all elements remaining in contact with each other. The middle region, clearly spaced from the anterior one, is made of two sets of lepidotrichia that show, as common characteristics, a few stout proximal segments followed by a section made up of very short segments (the “hinge area” in Lombardo [

48]). At least seven unsegmented rays emerge from the hinge area, making up the first group of the middle region. They are quite thin and branch distally, possibly twice, the distalmost elements bending forward. The second group of rays in this region shows the posteriorly directed hooks. Seven to eight segmented rays have the distal element modified as a large, stout hook, making an almost vertical posterior edge. The preservation does not allow precise restoration of the posterior region, but a few proximal segments (possibly three) are followed by short lepidotrichia, of which only scattered segments are visible. No fringing fulcra are present.

Dorsal fin. The dorsal fin is inserted well posterior to the anal fin, the first radial being around the vertebral column position of the last one of the anal fin (

Figure 3B and

Figure 4A). At least 10 radials are present, the first one being much larger than the following ones and with a bifurcated proximal region, in the same way as in the type series [

15]. As in the latter, this large radial appears to be just in front of the lepidotrichia, without giving support to any of the long rays. Owing to the twist of the posterior caudal region, rays are packed together, and no detailed description is possible.

Caudal fin. Owing to the twist of the vertebral column in the tail region, only the ventral lobe and part of the dorsal one are well preserved, the dorsalmost part of the caudal fin being preserved as scattered rays mixed with disarticulated scales from the left side of the caudal scale field. The fin is deeply forked, the ventral lobe rays being much stouter and packed than those in the dorsal one. The ventral margin is made of a few basal fulcra (possibly five) followed by four short, segmented elements. The leading ray is the longest, and it is followed by another four somewhat large rays of more or less the same length, all of them branching, possibly twice, only very distally. After these five rays, the other five in the ventral lobe become quickly shorter, and their branching starts very proximally after a very enlarged proximal triangular element. Thus, the ventral lobe is made up of 10 strictly packed rays with long segments, while the posterior margin is a fringe of very thin elements owing to strong distal branching. No fringing fulcra are visible. The median part of the dorsal lobe shows two rays similar to the last two in the ventral lobe, but these dorsal rays appear somewhat separated from each other. As said before, only scattered rays from the remaining part of the dorsal lobe are preserved along the ural region of the vertebral column.

Scales. The body was almost totally naked, and, as this specimen lacks the anterior region, it is not possible to check the presence of the antero-dorsal scale field described in the Chinese specimens [

15]. Only the caudal scale field is preserved ventrally to the vertebral column (

Figure 3B and

Figure 4C), as in the Chinese type series. The only difference appears to be in the number of rows, here 11. The first (anteriormost) two rows are much shorter, and the scales are smaller (8–9 scales per row), while the following four are the most important, with more than 10 large scales. The five posterior rows decrease in both the number of scales and the size of single scales. No peg and socket articulation is visible, and the scales appear to be just slightly superimposed on each other. The external surface is covered by a smooth layer of ganoine.