Patterns of Species Dominance in Two Coastal Restorations: Evidence of Sustained Seagrass Success over Long Time Scales

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Restoration at Study Sites

2.2. Site Monitoring

2.2.1. Lassing Park

2.2.2. Shell Key

2.3. Data Analysis

Dominance Index and Species Abundance

3. Results

3.1. Benthic Macrophyte: Identity and Abundance

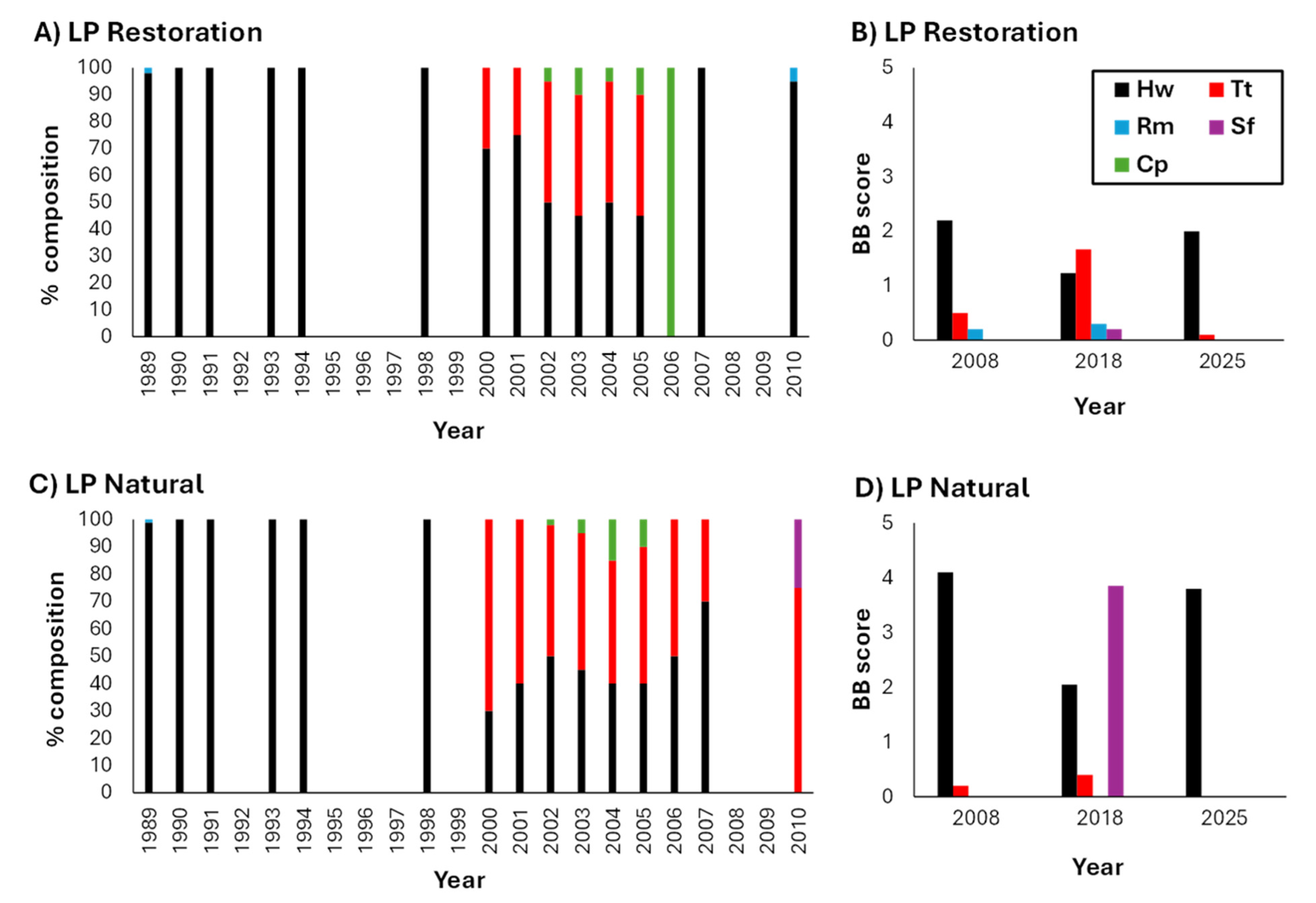

3.1.1. Lassing Park

3.1.2. Shell Key

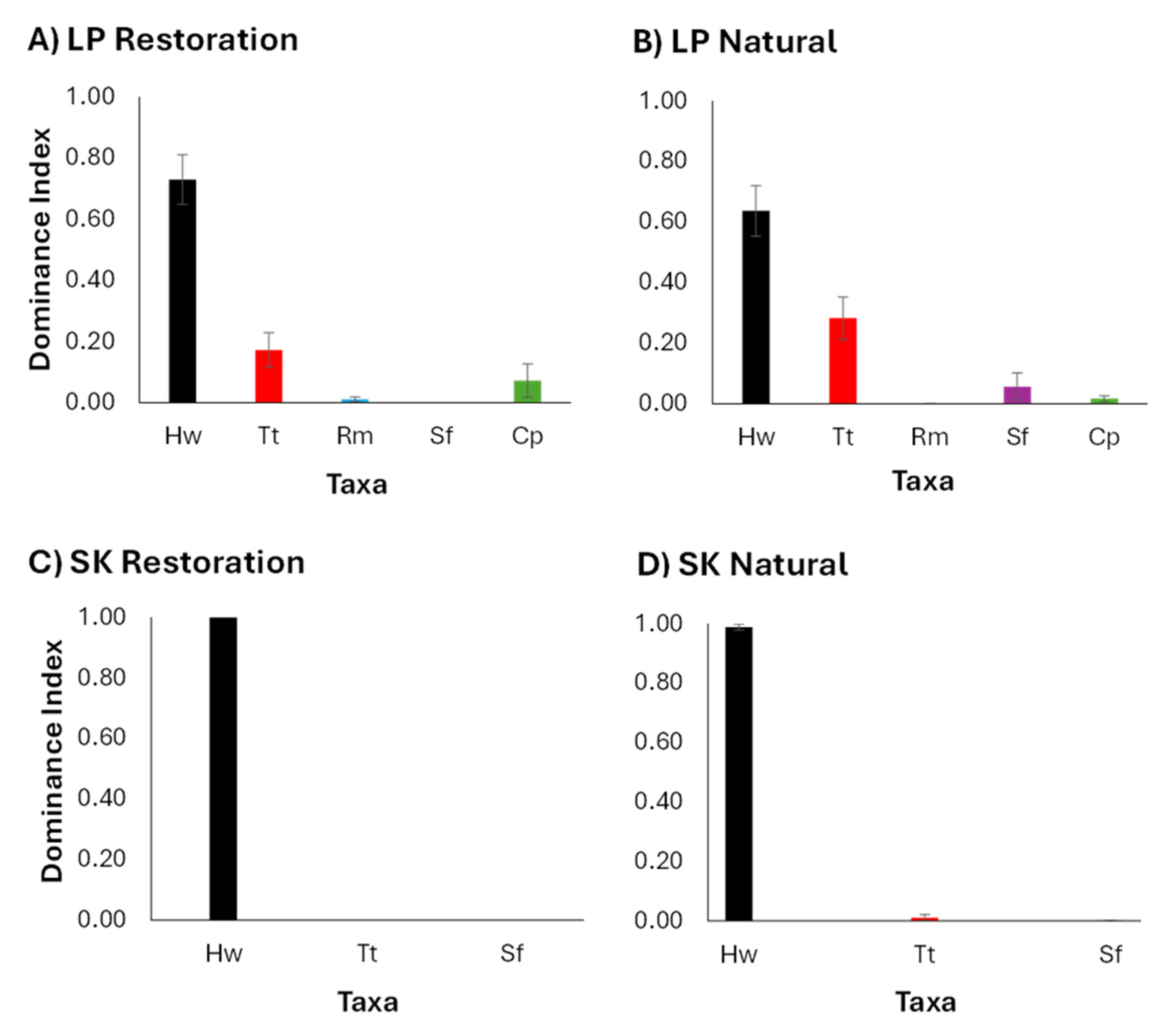

3.2. Benthic Macrophyte Dominance

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| N | North Latitude |

| W | West Longitude |

References

- do Amaral Camara Lima, M.; Bergamo, T.F.; Ward, R.D.; Joyce, C.B. A review of seagrass ecosystem services: Providing nature-based solutions for a changing world. Hydrobiologia 2023, 850, 2655–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkum, A.; Orth, R.; Duarte, C.M. Seagrasses; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, B.D. Quantifying temporal change in seagrass areal coverage: The use of GIS and low resolution aerial photography. Aquat. Bot. 1997, 58, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, L.J.; Hall, L.M.; Jacoby, C.A.; Chamberlain, R.H.; Hanisak, M.D.; Miller, J.D.; Virnstein, R.W. Seagrass in a changing estuary, the Indian River Lagoon, Florida, United States. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 8, 789818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerona-Daga, M.E.B.; Salmo, S.G. A systematic review of mangrove restoration studies in Southeast Asia: Challenges and opportunities for the United Nation’s Decade on Ecosystem Restoration. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 987737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Yin, B.; Chen, L.; Gasparatos, A. Priority areas for mixed-species mangrove restoration: The suitable species in the right sites. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 065001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausch, R. Testing strategies to enhance transplant success under stressful conditions at a tidal marsh restoration project. Restor. Ecol. 2024, 32, e14117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, K.E.; Parker, I.M.; Fountain, M.C.; Thomsen, A.S.; Wasson, K. Unfriendly neighbors: When facilitation does not contribute to restoration success in tidal marsh. Ecol. Appl. 2025, 35, e3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lirman, D.; Cropper, W.P. The Influence of Salinity on Seagrass Growth, Survivorship, and Distribution within Biscayne Bay, Florida: Field, Experimental, and Modeling Studies. Estuaries 2003, 26, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaldy, J.E.; Dunton, K.H.; Kowalski, J.L.; Lee, K.S. Factors controlling seagrass revegetation onto dredged material deposits: A case study in Lower Laguna Madre, Texas. Coast. Res. 2004, 20, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, K.V.D.S.; Rocha-Barreira, C.D.A. Influence of environmental factors on a Halodule wrightii Ascherson meadow in northeastern Brazil. BJAST 2014, 18, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezek, R.J.; Furman, B.T.; Jung, R.P.; Hall, M.O.; Bell, S.S. Long-term performance of seagrass restoration projects in Florida, USA. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Katwijk, M.M.; Thorhaug, A.; Marbà, N.; Orth, R.J.; Duarte, C.M.; Kendrick, G.A.; Al-thuizen, I.H.J.; Balestri, E.; Bernard, G.; Cambridge, M.L.; et al. Global analysis of seagrass restoration: The importance of large-scale planting. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 53, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudouresque, C.F.; Blanfuné, A.; Pergent, G.; Thibaut, T. Restoration of seagrass meadows in the Mediterranean Sea: A critical review of effectiveness and ethical issues. Water 2021, 13, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.; Beheshti, K. Lessons learned from over thirty years of eelgrass restoration on the US West Coast. Ecosphere 2023, 14, e4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, T.; Gransten, S.B.; Elbrønd, F.; Johnstad-Møller, C.A.; Christensen, C.V.; Brodersen, K.E. Effects of European green crabs (Carcinus maenas) on transplanted Eelgrass (Zostera marina): Potential protective measures. Restor. Ecol. 2025, 33, e70074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, M.S.; Whitfield, P.E.; Kenworthy, W.J.; Colby, D.R.; Julius, B.E. Use of two spatially explicit models to determine the effect of injury geometry on natural resource recovery. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2004, 14, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorhaug, A.; Belaire, C.; Verduin, J.J.; Schwarz, A.; Kiswara, W.; Prathep, A.; Gallagher, J.B.; Huang, X.P.; Berlyn, G.; Yap, T.-K.; et al. Longevity and sustainability of tropical and subtropical restored seagrass beds among Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 160, 111544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos, M.E.; Merino, M.; Rodriguez, A.; Marbà, N.; Duarte, C.M. Growth patterns and demography of pioneer Caribbean seagrasses Halodule wrightii and Syringodium filiforme. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1994, 109, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thom, R.M.; Diefenderfer, H.L.; Vavrinec, J.; Borde, A.B. Restoring Resiliency: Case Studies from Pacific Northwest Estuarine Eelgrass (Zostera marina L.). Ecosystems 2012, 35, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.S.; Middlebrooks, M.L.; Hall, M.O. The Value of Long-Term Assessment of Restoration: Support from a Seagrass Investigation. Restor. Ecol. 2014, 22, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacci, T.; Scardi, M.; Tomasello, A.; Valiante, L.M.; Piazzi, L.; Calvo, S.; Badalamenti, F.; di Nuzzo, F.; Raimondi, V.; Assenzo, M.; et al. Long-term response of Posidonia oceanica meadow restoration at the population and plant level: Implications for management decisions. Restor. Ecol. 2025, 33, e14360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendrick, G.A.; Austin, R.; Ferretto, G.; van Keulen, M.; Verduin, J.J. Lessons learnt from revisiting decades of seagrass restoration projects in Cockburn Sound, southwestern Australia. Restor. Ecol. 2025, 33, e70040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.O.; Bell, S.S.; Furman, B.T.; Durako, M.J. Natural recovery of a marine foundation species emerges decades after landscape-scale mortality. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, S.S.; Ann Clements, L.J.; Kurdziel, J. Production in Natural and Restored Seagrasses: A Case Study of a Macrobenthic Polychaete. Ecol. Appl. 1993, 3, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, S.S.; Tewfik, A.; Hall, M.O.; Fonseca, M.S. Evaluation of seagrass planting and monitoring techniques: Implications for assessing restoration success and habitat equivalency. Restor. Ecol. 2008, 16, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, M.S.; Kenworthy, W.J.; Courtney, F.X. Development of planted seagrass beds in Tampa Bay, Florida, USA. I. Plant components. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1996, 132, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, S.B. Seagrass Restoration at Lassing Park, St. Petersburg, Florida: Analysis After 13.5 Years. Master’s Thesis, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, C.L. (University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA); Bell, S.S. (University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA); Burns, B. (University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA); MacLeod, K. (University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA). Population genomics on Halodule wrightii Restoration. Unpublished report, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Tampa Bay Seagrass Transect Dashboard. Available online: https://tbep.org/seagrass-assessment/ (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Braun-Blanquet, J. Plant Sociology: The Study of Plant Communities; Fuller, G.D., Conard, H.S., Eds. and Translators; Authorized English translation of Pflanzensoziologie; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, J.; Jia, Z.; Ge, S.; Li, Y.; Kang, D.; Li, J. Dominant Species Composition, Environmental Characteristics and Dynamics of Forests with Picea jezoensis Trees in Northeast China. Diversity 2024, 16, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, B.T.; Leone, E.H.; Bell, S.S.; Durako, M.J.; Hall, M.O. Braun-Blanquet data in ANOVA designs: Comparisons with percent cover and transformations using simulated data. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2018, 597, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, N.B.; Bell, S.S. Space competition between seagrass and Caulerpa prolifera (Forsskaal) Lamouroux following simulated disturbances in Lassing Park, FL. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2006, 333, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, L.J.; Virnstein, R.W. The demise and recovery of seagrass in the northern Indian River Lagoon, Florida. Estuaries 2004, 27, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuya, F.; Hernandez-Zerpa, H.; Espino, F.; Haroun, R. Drastic decadal decline of the seagrass Cymodocea nodosa at Gran Canaria (eastern Atlantic): Interactions with the green algae Caulerpa prolifera. Aquat. Bot. 2013, 105, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, B.D.; Bell, S.S. Dynamics of a subtidal seagrass landscape: Seasonal and annual change in relation to water depth. Ecology 2000, 81, 1193–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virnstein, R.W. Seagrass landscape diversity in the Indian River Lagoon, Florida: The importance of geographic scale and pattern. Bull. Mar. Sci. 1995, 57, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lirman, D.; Thyberg, T.; Santos, R.; Schopmeyer, S.; Drury, C.; Collado-Vides, L.; Bellmund, S.; Serafy, J. SAV communities of western Biscayne Bay, Miami, Florida, USA: Human and natural drivers of seagrass and macroalgae abundance and distribution along a continuous shoreline. Estuaries Coasts 2014, 37, 1243–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onuf, C.P. Biomass patterns in seagrass meadows of the Laguna Madre, Texas. Bull. Mar. Sci. 1996, 58, 404–420. [Google Scholar]

- Congdon, V.M.; Hall, M.O.; Furman, B.T.; Campbell, J.E.; Durako, M.J.; Goodin, K.L.; Dunton, K.H. Common ecological indicators identify changes in seagrass condition following disturbances in the Gulf of Mexico. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 156, 111090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Survey Type | Number of Replicates | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| (A) LP Restoration | |||

| 1989–1990 | AGB cores | 24 | [25] |

| 1991, 1993, 1994, 1998 | AGB cores | 12 | * |

| 2000–2001 | AGB cores | 12 | [28] |

| 2002–2007 | AGB cores | 10 | * |

| 2008 | BB quadrats (v) | 10 | * |

| 2010 | AGB cores | 10 | * |

| 2018 | BB quadrats | 30 | [12] |

| 2025 | BB quadrats | 5 | [29] |

| (B) LP Natural | |||

| 1989–1990 | AGB cores | 24 | [25] |

| 1991, 1993, 1994, 1998 | AGB cores | 12 | * |

| 2000–2001 | AGB cores | 12 | [28] |

| 2002–2007 | AGB cores | 10 | * |

| 2008 | BB quadrats (v) | 10 | * |

| 2010 | AGB cores | 10 | * |

| 2018 | BB quadrats | 20 | [12] |

| 2025 | BB quadrats | 5 | [29] |

| (C) SK Restoration | |||

| 2002–2005 | BB points (12) | 6000 | [26] |

| 2006 | BB points (3) | 1500 | [21] |

| 2007–2009 | BB points (12) | 6000 | [21] |

| 2018 | BB quadrats | 30 | [12] |

| 2024–2025 | BB quadrats | 5 | [29] |

| (D) SK Natural | |||

| 2003 | BB quadrats | 18 | [31] |

| 2005 | BB quadrats | 10 | [31] |

| 2007 | BB quadrats | 15 | [31] |

| 2009 | BB quadrats | 16 | [31] |

| 2011 | BB quadrats | 16 | [31] |

| 2013 | BB quadrats | 11 | [31] |

| 2015 | BB quadrats | 9 | [31] |

| 2017 | BB quadrats | 8 | [31] |

| 2019 | BB quadrats | 11 | [31] |

| 2021 | BB quadrats | 14 | [31] |

| 2023 | BB quadrats | 15 | [31] |

| 2024–2025 | BB quadrats | 5 | [29] |

| LP | SK | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restoration | Natural | Restoration | Natural | |

| Halodule wrightii | 16 | 17 | 11 | 14 |

| Thalassia testudinum | 7 | 9 | 0 | 1 |

| Syringodium filiforme | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Caulerpa prolifera | 3 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bell, S.S.; MacLeod, K.L. Patterns of Species Dominance in Two Coastal Restorations: Evidence of Sustained Seagrass Success over Long Time Scales. Diversity 2025, 17, 832. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120832

Bell SS, MacLeod KL. Patterns of Species Dominance in Two Coastal Restorations: Evidence of Sustained Seagrass Success over Long Time Scales. Diversity. 2025; 17(12):832. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120832

Chicago/Turabian StyleBell, Susan S., and Kasey L. MacLeod. 2025. "Patterns of Species Dominance in Two Coastal Restorations: Evidence of Sustained Seagrass Success over Long Time Scales" Diversity 17, no. 12: 832. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120832

APA StyleBell, S. S., & MacLeod, K. L. (2025). Patterns of Species Dominance in Two Coastal Restorations: Evidence of Sustained Seagrass Success over Long Time Scales. Diversity, 17(12), 832. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120832