Interactions Between Invasive Plants and Native Plants on the Northern Coast of China and Their Implications for Ecological Restoration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description

2.2. Experimental Approach

2.2.1. Sampling and Planting

2.2.2. Experimental Design

2.2.3. Data Collection and Organization

2.2.4. Statistics and Analysis

3. Results

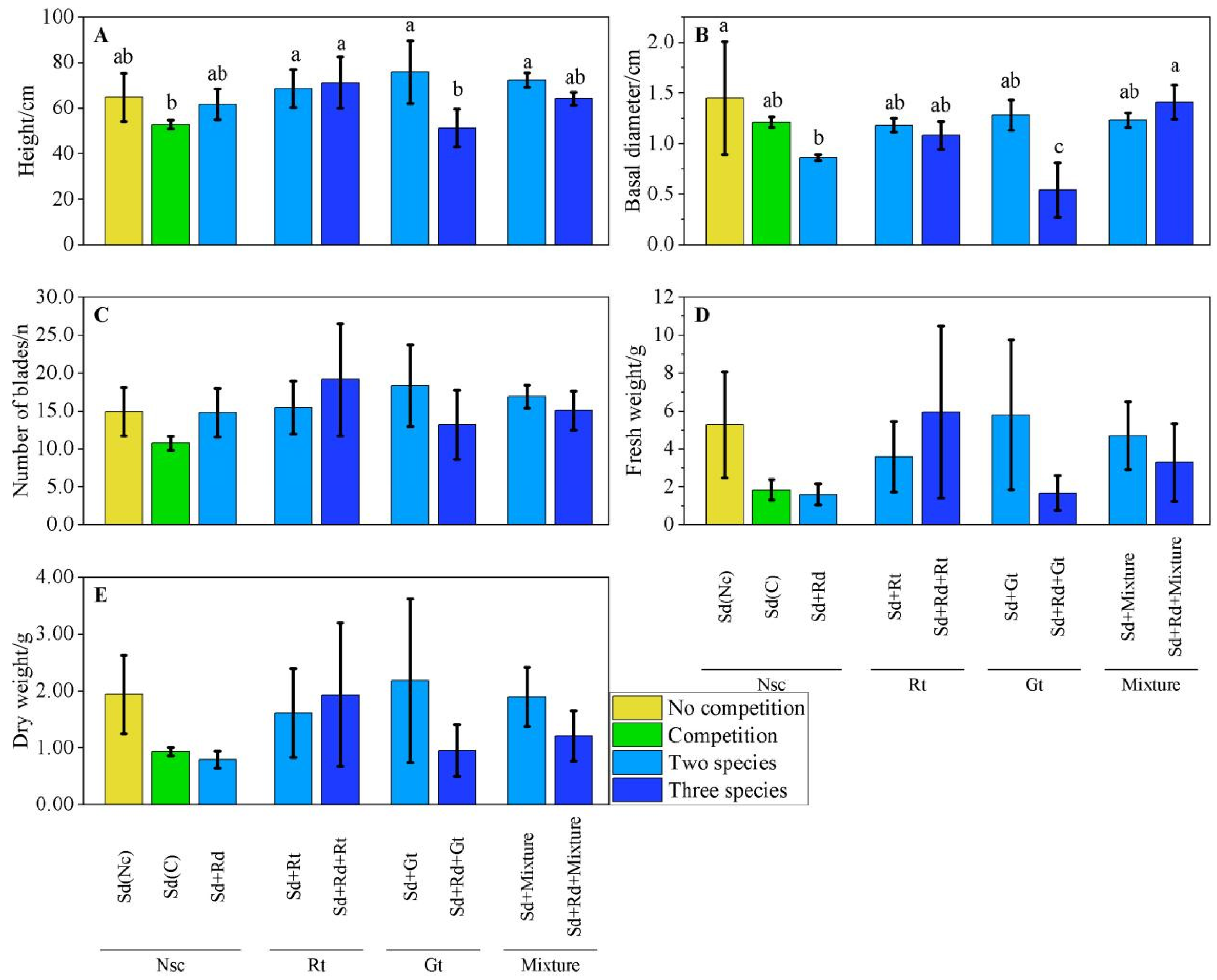

3.1. Growth Measures Comparison

3.2. Competitiveness of S. alterniflora

3.3. Measures Performance in Various Scenarios

3.3.1. Performance of S. alterniflora

3.3.2. Performance of P. australis

3.3.3. Performance of S. salsa

4. Discussion

4.1. Competitiveness in Different Reproductive Methods

4.2. Competitiveness in Different Competitive Treatments

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gratton, C.; Denno, R.F. Restoration of Arthropod Assemblages in a Spartina Salt Marsh following Removal of the Invasive Plant Phragmites australis. Restor. Ecol. 2005, 13, 358–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zedler, J.B.; Kercher, S. Causes and consequences of invasive plants in wetlands: Opportunities, opportunists, and outcomes. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2004, 23, 431–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, E.; Sun, S.; Li, B. Invasive alien plants in China: Diversity and ecological insights. Biol. Invasions 2008, 10, 1411–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Liu, H.; Jiao, F.; Lin, Z.; Xu, X. Pure, shared and coupling effects of climate change and sea level rise on the future distribution of Spartina alterniflora along the Chinese coast. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 5380–5391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Wang, W.; Song, Z.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Guo, L.; Van Zwieten, L.; Li, Q.; Hartley, I.P.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Spartina alterniflora invasion controls organic carbon stocks in coastal marsh and mangrove soils across tropics and subtropics. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 1627–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, X.; Chen, J.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, J. Impact of applying imazapyr on the control of Spartina alterniflora and its eco-environments in the Yellow River Delta, China. Watershed Ecol. Environ. 2022, 4, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Z.; Xie, T.; Liu, Z.; Bai, J.; Cui, B. Native herbivores enhance the resistance of an anthropogenically disturbed salt marsh to Spartina alterniflora invasion. Ecosphere 2019, 10, e02565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallott, P.G.; Jeffries, A.J.; Hotton, N.J. Carbon dioxide exchange in leaves of Spartina anglica Hubbard. Oecology 1975, 20, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, S.P.; Incoll, L.D.; Woolhouse, H.W. C4 photosynthesis in plants from cool temperature regions, with particular reference to Spartina townsendii. Nature 1975, 257, 622–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomeroy, L.R.; Wiegert, R.G. The Ecology of a Salt Marsh; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1981; pp. 39–67. [Google Scholar]

- Svanbäck, R.; Bolnick, D.I. Intraspecific competition drivers increased resource use diversity within a natural population. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2007, 274, 839–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zeng, H.; Zhao, F.; Chen, C.; Singh, A.K.; Jiang, X.; Yang, B.; Liu, W. Plant hydrological niches become narrow but stable as the complexity of interspecific competition increases. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 320, 108953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Du, Y.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Du, D. Co-invasion of three invasive alien plants increases plant taxonomic diversity and community invasibility. Plant Divers. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Liu, G.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, C.; Ye, X.; Zhu, Z. Phylogenetically close alien Asteraceae species with minimal niche overlap are more likely to invade. Plant Divers. 2025, 47, 804–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Gao, J.; Guo, Y.; Liang, J.; Yu, F. Effects of biochar on nitrogen competition between invasive Spartina alterniflora and native Phragmites australis. J. Plant Ecol. 2025, 18, rtaf063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Gao, Y.; Li, B.; Wang, C.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, B. Spartina alterniflora with high tolerance to salt stress changes vegetation pattern by outcompeting native species. Ecosphere 2014, 5, art116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wails, C.N.; Baker, K.; Blackburn, R.; Del Vallé, A.; Heise, J.; Herakovich, H.; Holthuijzen, W.A.; Nissenbaum, M.P.; Rankin, L.; Savage, K.; et al. Assessing changes to ecosystem structure and function following invasion by Spartina alterniflora and Phragmites australis: A meta-analysis. Biol. Invasions 2021, 23, 2695–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.J.; Qing, H.; Zhao, C.J.; Zhou, C.F.; Zhang, W.G.; Xiao, Y.; An, S.Q. Phenotypic plasticity of Spartina alterniflora and Phragmites australis in response to nitrogen addition and intraspecific competition. Hydrobiologia 2010, 637, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, X.; Liang, J.; Gao, J.; Xu, X.; Yu, F. High nitrogen uptake and utilization contribute to the dominance of invasive Spartina alterniflora over native Phragmites australis. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2021, 57, 1007–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckee, K.L.; Patrick, W.H. The relationship of smooth cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora) to tidal datums: A review. Estuaries 1988, 11, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, E.A.; Glenn, E.P.; Guntenspergen, G.R.; Brown, J.J.; Nelson, S.G. Salt tolerance and osmotic adjustment of Spartina alterniflora (Poaceae) and the invasive M haplotype of Phragmites australis (Poaceae) along a salinity gradient. Am. J. Bot. 2006, 93, 1784–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, Y.; An, S.; Zhi, Y.; Lei, G.; Zhang, M. Sediment type affects competition between a native and an exotic species in coastal China. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 6748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, L.S.C.; Camargo, A.F.M. The interspecific competition of tropical estuarine macrophytes is not density-dependent. Aquat. Bot. 2020, 164, 103233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, G.; Zhao, C. Identification of Spartina alterniflora habitat expansion in a Suaeda salsa dominated coastal wetlands. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 145, 109704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Z.; Cui, L.; Li, W.; Lei, Y.; Zuo, X.; Cai, Y.; Yan, R. Effect of freshwater on plant species diversity and interspecific associations in coastal wetlands invaded by Spartina alterniflora. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 965426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, B. The influence of nutrient addition on the invasion of “Spartina alterniflora” towards the non-tidal wetlands in the Chinese Yellow River delta. J. Coast. Conserv. 2019, 23, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C. Coastal wetland conservation in Tangshan. Wetl. Sci. Manag. 2006, 2, 28–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Y. Landscape Pattern Evolution and Ecosystem Health Assessment of Coastal Wetlands in Hebei Province, China. Master’s Thesis, Hebei GEO University, Shijiazhuang, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Tian, D. Spatio-temporal dynamics of Spartina alterniflora in Tianjin-Hebei coastal area. Remote Sens. Technol. Appl. 2025, 40, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, M.G.; Tron, F.; Mauchamp, A. Sexual versus asexual colonization by Phragmites australis: 25-year reed dynamics in a mediterranean marsh, southern France. Wetlands 2005, 25, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Wang, B. Using euhalophytes to understand salt tolerance and to develop saline agriculture: Suaeda salsa as a promising model. Ann. Bot. 2015, 115, 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhao, H.; Yang, W.; Qing, H.; Zhou, C.; Tang, J.; An, S. Variations in growth, clonal and sexual reproduction of Spartina alterniflora responding to changes in clonal integration and sand burial. Clean-Soil Air Water 2015, 43, 1100–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crombie, A.C. Interspecific Competition. J. Anim. Ecol. 1947, 16, 44–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald, C.M. Competition among crop and pasture plants. Adv. Agron. 1963, 15, 1–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, N. Competition and Coexistence in a North Carolina Grassland: III. Mixtures of Component Species. J. Ecol. 1982, 70, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.B. Shoot Competition and Root Competition. J. Appl. Ecol. 1988, 25, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wit, C.T.D.; Bergh, J.P.V.D. Competition between herbage plants. Neth. J. Agric. Sci. 1965, 13, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, B.; Xie, T.; Ning, Z.; Cui, B.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Gao, F.; Zhang, S.; Lu, Y. Invasion patterns of Spartina alterniflora: Response of clones and seedlings to flooding and salinity—A case study in the Yellow River Delta, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 877, 162803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wang, G.; Liu, J.; Chen, Z.; Hang, Z.; Wang, H. Two reproductive mode of Spartina alterniflora on coastal wetland of North Jiangsu. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2014, 34, 3839–3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautiainen, P.; Koivula, K.; Hyvarinen, M. Effect of within-genet and between-genet competition on sexual reproduction and vegetative spread in Potentilla anserina ssp. egedii. J. Ecol. 2004, 92, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, K.A. Shade avoidance. New Phytol. 2008, 179, 930–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiner, J. Allocation, plasticity and allometry in plants. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2004, 6, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsberry, L.; Baker, M.A.; Ewanchuk, P.J.; Bertness, M.D. Clonal Integration and the Expansion of Phragmites australis. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 1110–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trnková, V. Co-connected Spaces. Serdica Math. J. 1998, 24, 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Pennings, S.C.; Callaway, R.M. The advantages of clonal integration under different ecological conditions: A community-wide test. Ecology 2000, 81, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Wang, K.; Li, D.; Pan, Y.; Lv, Y.; Zhao, M.; Gao, J. Interspecific Interactions between Phragmites australis and Spartina alterniflora along a Tidal Gradient in the Dongtan Wetland, Eastern China. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legault, R.; Zogg, G.P.; Travis, S.E. Competitive interactions between native Spartina alterniflora and non-native Phragmites australis depend on nutrient loading and temperature. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, C.R.; Burdick, D.M. Can Plant Competition and Diversity Reduce the Growth and Survival of Exotic Phragmites australis Invading a Tidal Marsh? Estuaries Coasts 2010, 33, 1225–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falik, O.; Reides, P.; Gersani, M.; Novoplansky, A. Self/Non-Self Discrimination in Roots. J. Ecol. 2003, 91, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahall, B.E.; Callaway, R.M. Effects of Regional Origin and Genotype on Intraspecific Root Communication in the Desert Shrub Ambrosia dumosa (Asteraceae). Am. J. Bot. 1996, 83, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Roij-Van Der Goes, P.; van der Putten, W.; Peters, B. Effects of sand deposition on the interaction between Ammophila arenaria, plant-parasitic nematodes and pathogenic fungi. Can. J. Bot. 1995, 73, 1141–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Formula | Code |

|---|---|

| = | (1) |

| A = RYab − RYba | (2) |

| Variables | S. alterniflora | P. australis | S. salsa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | p | M | SD | p | M | SD | p | |

| Height | 56.42 | 5.81 | 0.012 | 61.61 | 4.28 | 0.550 | 52.75 | 1.92 | 0.019 |

| Basal diameter | 1.19 | 0.08 | 0.000 | 0.93 | 0.19 | 0.014 | 1.21 | 0.05 | 0.000 |

| Number of blades | 6.72 | 0.26 | 0.012 | 9.32 | 0.44 | 0.463 | 10.75 | 0.93 | 0.356 |

| Fresh weight | 3.88 | 0.28 | 0.000 | 0.99 | 0.13 | 0.798 | 1.83 | 0.54 | 0.248 |

| Dry weight | 1.36 | 0.12 | 0.000 | 0.60 | 0.1 | 0.877 | 0.93 | 0.07 | 0.370 |

| Variables | Height | Basal Diameter | Number of Blades | Fresh Weight | Dry Weight | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | p | R2 | p | R2 | p | R2 | p | R2 | p | |

| G1 | 0.094 | 0.055 | 0.435 | 0.001 | 0.025 | 0.514 | 0.424 | 0.001 | 0.501 | 0.001 |

| G2 | 0.159 | 0.048 | 0.236 | 0.007 | 0.260 | 0.001 | 0.047 | 0.622 | 0.013 | 0.952 |

| G1:G2 | 0.179 | 0.117 | 0.114 | 0.016 | 0.146 | 0.198 | 0.093 | 0.324 | 0.089 | 0.295 |

| Scenarios | Measures | M | SD | A | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ramets + Reeds | Height | 51.93 | 6.70 | 0.768 | −0.209 |

| Basal diameter | 1.66 | 0.18 | 1.092 | 0.070 | |

| Number of blades | 5.93 | 0.74 | 0.829 | −0.210 | |

| Fresh weight | 3.52 | 0.79 | 0.846 | −0.366 | |

| Dry weight | 1.75 | 0.20 | 1.094 | 0.027 | |

| Ramets + Seepweed | Height | 70.80 | 22.05 | 1.046 | −0.255 |

| Basal diameter | 1.33 | 0.13 | 0.875 | −0.100 | |

| Number of blades | 8.01 | 1.17 | 1.120 | −0.313 | |

| Fresh weight | 4.38 | 2.18 | 1.053 | −0.903 | |

| Dry weight | 2.41 | 1.51 | 1.452 | −0.279 | |

| Genets + Reeds | Height | 66.32 | 7.34 | 1.698 | 0.663 |

| Basal diameter | 1.36 | 0.09 | 1.679 | 0.550 | |

| Number of blades | 7.11 | 0.52 | 1.183 | 0.095 | |

| Fresh weight | 2.38 | 0.09 | 1.286 | 0.064 | |

| Dry weight | 0.78 | 0.07 | 1.068 | 0.218 | |

| Genets + Seepweed | Height | 56.16 | 5.18 | 1.438 | 0.001 |

| Basal diameter | 1.04 | 0.27 | 1.284 | 0.226 | |

| Number of blades | 6.89 | 0.58 | 1.146 | −0.560 | |

| Fresh weight | 1.56 | 0.65 | 0.843 | −2.321 | |

| Dry weight | 0.47 | 0.18 | 0.644 | −1.700 | |

| Mixture + Reeds | Height | 61.24 | 12.36 | 1.085 | 0.051 |

| Basal diameter | 1.64 | 0.14 | 1.378 | 0.475 | |

| Number of blades | 9.14 | 3.95 | 1.360 | 0.053 | |

| Fresh weight | 4.35 | 1.32 | 1.121 | −0.051 | |

| Dry weight | 2.1 | 0.99 | 1.544 | 0.627 | |

| Mixture + Seepweed | Height | 67.71 | 6.61 | 1.200 | −0.169 |

| Basal diameter | 1.3 | 0.05 | 1.092 | 0.075 | |

| Number of blades | 7.28 | 0.33 | 1.083 | −0.487 | |

| Fresh weight | 3.65 | 0.49 | 0.941 | −1.622 | |

| Dry weight | 1.62 | 0.25 | 1.191 | −0.852 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Hou, S.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, G.; Zhang, M.; Mo, X.; Zhang, N.; et al. Interactions Between Invasive Plants and Native Plants on the Northern Coast of China and Their Implications for Ecological Restoration. Diversity 2025, 17, 765. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17110765

Li X, Hou S, Li S, Zhang Y, Zhang D, Zhang S, Zheng G, Zhang M, Mo X, Zhang N, et al. Interactions Between Invasive Plants and Native Plants on the Northern Coast of China and Their Implications for Ecological Restoration. Diversity. 2025; 17(11):765. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17110765

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xiuzhong, Shuailing Hou, Senyang Li, Yufei Zhang, Duoli Zhang, Shen Zhang, Guoxiang Zheng, Mingxiang Zhang, Xue Mo, Nan Zhang, and et al. 2025. "Interactions Between Invasive Plants and Native Plants on the Northern Coast of China and Their Implications for Ecological Restoration" Diversity 17, no. 11: 765. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17110765

APA StyleLi, X., Hou, S., Li, S., Zhang, Y., Zhang, D., Zhang, S., Zheng, G., Zhang, M., Mo, X., Zhang, N., Dai, H., Xue, J., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Interactions Between Invasive Plants and Native Plants on the Northern Coast of China and Their Implications for Ecological Restoration. Diversity, 17(11), 765. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17110765