Tardigrades (Tardigrada) of Colombia: Historical Overview, Distribution, New Records, and an Updated Taxonomic Checklist

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Historical Reconstruction, Distribution of Tardigrades, and Development of an Updated Checklist

2.2. Exploration of Novel Tardigrade Records

3. Results

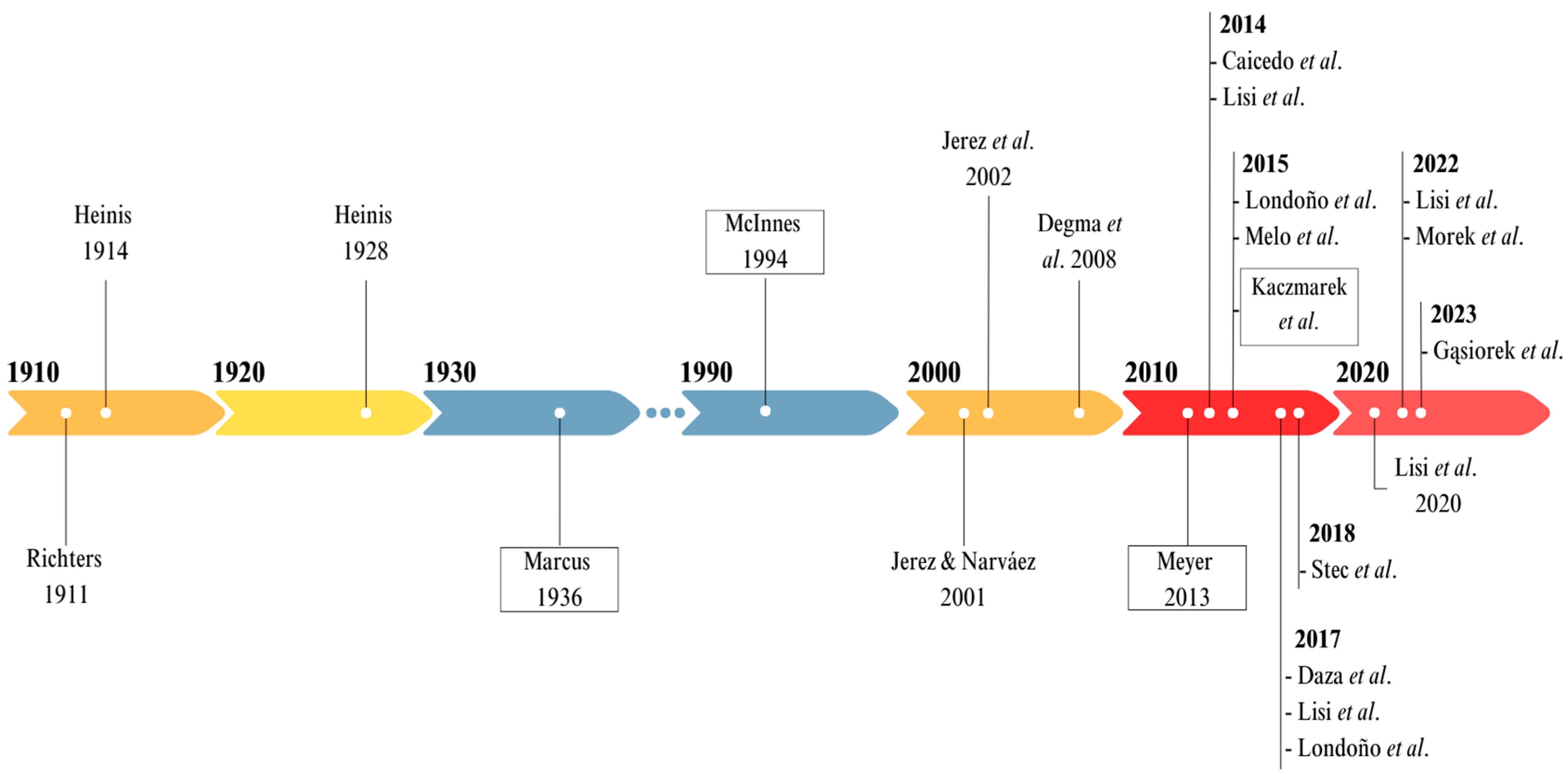

3.1. History

| Taxa | Department | Recorded by | Invalidated or Questioned by |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tardigrada Doyère, 1840 Heterotardigrada Marcus, 1927 Echiniscoidea Richters, 1926 Echiniscidae Thulin, 1928 | |||

| * Barbaria bigranulata (Richters, 1907) | CUN | [38] | [40] |

| * Claxtonia cf. wendti (Richters, 1903) | TOL | [21] | [18,40] |

| Echiniscus blumi blumi Richters, 1903 | ANT | [23] | [18,40] |

| ** Echiniscus fischeri Richters, 1911 | ANT | [23] | This paper |

| Echiniscus quadrispinosus Richters, 1902 | ANT, CUN | [23] | [18,40] |

| Echiniscus spiniger Richters, 1904 | CUN | [23] | [18,40] |

| Echiniscus testudo (Doyère, 1840) | ANT, CUN, VAC | [23,39] | [18,40] |

| Echiniscus virginicus Riggin, 1962 | MAG | [48] | [34] |

| Echiniscus sp. | MAG | [47] | This paper |

| Pseudechiniscus sp. | TOL | [23,39] | This paper |

| Pseudechiniscus brevimontanus Kendall-Fite & Nelson, 1996 | CUN, DC | [16,23] | This paper |

| Pseudechiniscus novaezeelandiae (Richters, 1908) | ANT, SAN, TOL | [22,23,45] | [40] |

| ** Pseudechiniscus novaezeelandiae aspinosa Iharos, 1963 | MAG | [47] | This paper |

| * Pseudechiniscus suillus (Ehrenberg, 1853) | ANT, CUN, SAN, VAC | [21,22,23] | [18,40] |

| Eutardigrada Richters, 1926 Apochela Schuster, Nelson, Grigarick & Christenberry, 1980 Milnesiidae Ramazzotti, 1962 | |||

| Milnesium cf. barbadosense Meyer & Hilton, 2012 | ATL, BOL CES, MAG | [52] | This paper |

| Milnesium tardigradum Doyère, 1840 | SAN | [45] | [18] |

| Milnesium tardigradum sensu lato Doyère, 1840 | ANT, CUN | [23] | [18,40] |

| Milnesium sp. | MAG | [47] | This paper |

| Milnesium sp. | MAG | [48] | This paper |

| Parachela Schuster, Nelson, Grigarick & Christenberry, 1980 Calohypsibiidae Pilato, 1969 | |||

| * Calohypsibius ornatus (Richters, 1900) | CUN | [23] | [18] |

| Hypsibiidae Pilato, 1969 | |||

| ** Diphascon chilenense Plate, 1888 | ANT, CUN, TOL | [22,23] | This paper |

| Diphascon higginsi Binda, 1971 | MAG | [48] | This paper |

| Diphascon sp. pingue group | MAG | [20] | This paper |

| Diphascon pingue pingue sensu lato (Marcus, 1936) | MAG | [20] | This paper |

| Hypsibius sp. | SAN | [45] | This paper |

| Hypsibius cf. allisoni Horning, Schuster & Grigarick, 1978 | MAG | [20] | This paper |

| Hypsibius dujardini (Doyère, 1840) | CUN | [40] | [18,42] |

| ** Hypsibius fuhrmanni (Heinis, 1914) | ANT | [23] | [18,42] |

| Acutuncidae Vecchi, Tsvetkova, Stec, Ferrari, Calhim, Tumanov, 2023 | |||

| * Acutuncus antarcticus (Richters, 1904) | ANT | [18] | [18,40] |

| Itaquasconidae Bartoš {in Rudescu, 1964} | |||

| * Adropion scoticum (Murray, 1905) | CUN | [23] | [18,40] |

| Itaquascon sp. | SAN | [45] | This paper |

| Pilatobiidae Bertolani, Guidetti, Marchioro, Altiero, Rebecchi & Cesari, 2014 | |||

| * Notahypsibius arcticus (Murray, 1907) | ANT, SAN | [23,45] | [18] |

| Doryphoribiidae Gąsiorek, Stec, Morek & Michalczyk, 2019 | |||

| Doryphoribius sp. evelinae group | MAG | [47] | This paper |

| Doryphoribius sp. vietnamensis group | MAG | [47] | This paper |

| Isohypsibiidae Sands, McInnes, Marley, Goodall-Copestake, Convey & Linse, 2008 | |||

| Dianea sattleri sensu lato (Richters, 1902) | MAG | [20,48] | [18] |

| Fractonotus sp. | MAG | [20] | This paper |

| Fractonotus verrucosus (Richters, 1900) | SAN | [45] | [18,40] |

| Isohypsibius prosostomus Thulin, 1928 | SAN | [45] | [18,40] |

| Macrobiotidae Thulin, 1928 | |||

| Calcarobiotus sp. | MAG | [47] | This paper |

| Macrobiotus cf. occidentalis Murray, 1910 | SAN | [45] | [18] |

| Macrobiotus echinogenitus Richters, 1903 | ANT, CUN, SAN, TOL | [22,23] | [18,40] |

| Macrobiotus hufelandi C.A.S. Schultze, 1834 | ANT, SAN, TOL | [22,23,45] | [18,40] |

| Macrobiotus cf. hufelandi C.A.S. Schultze, 1834 | CUN | [40] | This paper |

| Macrobiotus sp. | CUN | [23] | This paper |

| Macrobiotus sp. 1 | MAG | [48] | This paper |

| Macrobiotus sp. 2 | MAG | [48] | This paper |

| Macrobiotus sp. 1 hufelandi group | MAG | [47] | This paper |

| Macrobiotus sp. 2 hufelandi group | MAG | [47] | This paper |

| ** Macrobiotus rubens Murray, 1907 | TOL | [23] | [18,40,43] |

| Mesobiotus harmsworthi (Murray, 1907) | CUN, SAN | [22,45] | [18,40] |

| * Mesobiotus sp. | MAG | [48] | This paper |

| Minibiotus intermedius (Plate, 1888) | ANT, CUN, MAG, SAN, TOL | [23,45,47] | [18] |

| Minibiotus cf. pilatus Claxton, 1998 | MAG | [48] | This paper |

| Minibiotus sp. | MAG | [48] | This paper |

| Paramacrobiotus areolatus (Murray, 1907) | SAN | [45] | [18,40] |

| Paramacrobiotus richtersi (Murray, 1911) | SAN | [45] | This paper |

| Paramacrobiotus areolatus group | MAG | [47] | This paper |

| Paramacrobiotus richtersi group | MAG | [47] | This paper |

| Murrayidae Guidetti, Rebecchi & Bertolani, 2000 | |||

| * Murrayon pullari (Murray, 1907) | ANT | [23] | [18] |

| Richtersiusidae Guidetti, Schill, Giovannini, Massa, Goldoni, Ebel, Förschler, Rebecchi & Cesari, 2021 | |||

| * Diaforobiotus islandicus (Richters, 1904) | SAN | [45] | [18] |

| * Diaforobiotus cf. islandicus (Richters, 1904) | CUN | [40] | This paper |

| * Richtersius coronifer (Richters, 1903) | CAU | [23] | [18,40] |

| Ramazzottidae Sands, McInnes, Marley, Goodall-Copestake, Convey & Linse, 2008 | |||

| Ramazzottius oberhaeuseri (Doyère, 1840) | ANT, CAU, TOL | [23] | [18,40] |

| Taxa | Department | Distribution | Scientific Collection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tardigrada Doyère, 1840 Heterotardigrada Marcus, 1927 Echiniscoidea Richters, 1926 Echiniscidae Thulin, 1928 | |||

| 1. Barbaria bigranulata (Richters, 1907) | CUN [40] | Cosmopolitan | CŁK, IGH |

| 2. Barbaria madonnae (Michalczyk & Kaczmarek, 2006) | MAG [48] | Neotropical | CCC |

| 3. Bryodelphax kristenseni Lisi, Daza, Londoño & Quiroga, 2017 | CES [32] | Endemic | CCC |

| MAG [32] | CCC | ||

| BOL (This paper) | CCC | ||

| 4. * Echiniscus lineatus Pilato, Fontoura, Lisi & Beasley, 2008 | MAG [32,48] | Pantropical | CCC |

| 5. Echiniscus perarmatus Murray, 1907 | MAG [32] | Cosmopolitan | CCC |

| 6. Kristenseniscus kofordi (Schuster & Grigarick, 1966) | CES [32] | Neartic; Neotropical | CCC |

| BOL (This paper) | CCC | ||

| SUC (This paper) | CCC | ||

| 7. Pseudechiniscus santomensis Fontoura, Pilato & Lisi, 2010 | MAG (This paper) | Neotropical | CCC |

| Eutardigrada Richters, 1926 Apochela Schuster, Nelson, Grigarick & Christenberry, 1980 Milnesiidae Ramazzotti, 1962 | |||

| 8. Milnesium brachyungue Binda & Pilato, 1990 | MAG [52] | Neotropical | CCC |

| 9. Milnesium granulatum Ramazzotti, 1962 | CUN [40] | Neotropical, Neartic, and Mediterranean | CŁK, IGH |

| 10. Milnesium katarzynae Kaczmarek, Michalczyk & Beasley, 2004 | ATL (This paper) | Pantropical | CCC |

| CUN [40] | CŁK, IGH | ||

| MAG [47,52] | CCC | ||

| 11. Milnesium kogui Londoño, Daza, Caicedo, Quiroga & Kaczmarek, 2015 | MAG [52] | Neotropical | CCC |

| 12. Milnesium krzysztofi Kaczmarek & Michalczyk, 2007 | CUN [40] | Neotropical | CŁK, IGH |

| MAG [48] | CCC | ||

| Parachela Schuster, Nelson, Grigarick & Christenberry, 1980 Hypsibiidae Pilato, 1969 | |||

| 13. Mixibius gibbosus Lisi, Daza, Londoño & Quiroga, 2022 | MAG [20] | Endemic | CCC |

| Itaquasconidae Bartoš {in Rudescu, 1964} | |||

| 14. Adropion onorei (Pilato, Binda, Napolitano & Moncada, 2002) | MAG [20] | Neotropical | CCC |

| 15. Itaquascon pilatoi Lisi, Londoño & Quiroga, 2014 | MAG [48] | Endemic | CCC |

| 16. Platicrista aluna (Lisi, Daza, Londoño, Quiroga & Pilato, 2019) | MAG [55] | Endemic | CCC |

| Doryphoribiidae Gąsiorek, Stec, Morek & Michalczyk, 2019 | |||

| 17. Doryphoribius amazzonicus Lisi, 2011 | CES [20] | Neotropical | CCC |

| MAG [48] | CCC | ||

| 18. Doryphoribius gibber Beasley & Pilato, 1987 | MAG [31] | Neartic; Neotropical | CCC |

| 19. Doryphoribius quadrituberculatus Kaczmarek & Michalczyk, 2004 | MAG [47] | Cosmopolitan | CCC |

| 20. Doryphoribius rosanae Daza, Caicedo, Lisi & Quiroga, 2017 | ANT (This paper) | Endemic | CLUA |

| CES [31] | CCC | ||

| MAG [31] | CCC | ||

| Adorybiotidae Stec, Vecchi & Michalczyk, 2020 | |||

| 21. ** Crenubiotus revelator Lisi, Londoño & Quiroga, 2020 | MAG [57] | Endemic | CCC |

| Macrobiotidae Thulin, 1928 | |||

| 22. Minibiotus pentannulatus Londoño, Daza, Lisi & Quiroga, 2017 | MAG [56] | Pantropical | CCC |

| 23. Paramacrobiotus danielae Pilato, Binda, Napolitano & Moncada, 2001 | CUN [40] | Neotropical | CŁK, IGH |

| 24. Paramacrobiotus derkai (Degma, Michalczyk & Kaczmarek, 2008) | BOY [53] | Endemic | CŁK, CŁM, CB&P, DZC, IAvH, and NHMD |

| 25. Paramacrobiotus lachowskae Stec, Roszkowska, Kaczmarek & Michalczyk, 2018 | MAG [54] | Endemic | DE.IZBR, DATE |

| 26. Paramacrobiotus sagani Daza, Caicedo, Lisi & Quiroga, 2017 | MAG [31] | Endemic | CCC |

3.2. Faunistic Account

| Taxa | Locality | Collection |

|---|---|---|

| Tardigrada Doyère, 1840 Heterotardigrada Marcus, 1927 Echiniscoidea Richters, 1926 Echiniscidae Thulin, 1928 | ||

| 1. Barbaria cf. rufoviridis (du Bois Reymond Marcus, 1944) | ANT (This paper) | CLUA |

| 2. Claxtonia sp. 1 | BOY [58] | DZC |

| 3. Pseudechiniscus novaezeelandiae aspinosa Iharos, 1963 | MAG [47] | CCC |

| Eutardigrada Richters, 1926 Apochela Schuster, Nelson, Grigarick & Christenberry, 1980 Milnesiidae Ramazzotti, 1962 | ||

| 4. Milnesium sp. nov. | PUT [59] | CŁK, IGH |

| 5. Milnesium cf. barbadosense Meyer & Hilton, 2012 | ATL, BOL (This paper); CES, MAG [54] | CCC |

| Parachela Schuster, Nelson, Grigarick & Christenberry, 1980 Calohypsibiidae Pilato, 1969 | ||

| 6. Calohypsibius ornatus (Richters, 1900) | CUN [23] | Without material |

| Hypsibiidae Pilato, 1969 | ||

| 7. Diphascon chilenense Plate, 1888 | ANT, CUN, TOL [22,23] | Without material |

| 8. Diphascon pingue pingue sensu lato (Marcus, 1936) | MAG [20] | CCC |

| 9. Diphascon sp. pingue group | MAG [20] | CCC |

| 10. Hypsibius cf. allisoni Horning, Schuster & Grigarick, 1978 | MAG [20] | CCC |

| Itaquasconidae Bartoš {in Rudescu, 1964} | ||

| 11. Notahypsibius arcticus (Murray, 1907) | ANT, SAN [23,45] | Without material |

| Isohypsibiidae Sands, McInnes, Marley, Marley, Goodall-Copestake, Convey & Linse, 2008 | ||

| 12. Dianea sattleri sensu lato (Richters, 1902) | MAG [20,48] | CCC |

| 13. Fractonotus verrucosus (Richters, 1900) | SAN [45] | Without material |

| Macrobiotidae Thulin, 1928 | ||

| 14. Minibiotus cf. pilatus Claxton, 1998 | MAG [48] | CCC |

| 15. Minibiotus intermedius (Plate, 1888) | ANT, CAU, CUN, TOL [23]; MAG [47]; SAN [45] | CCC |

| Richtersiusidae Guidetti, Schill, Giovannini, Massa, Goldoni, Ebel, Förschler, Rebecchi & Cesari, 2021 | ||

| 16. Diaforobiotus cf. islandicus (Richters, 1904) | CUN [40] | CŁK, IGH |

| Ramazzottidae Sands, McInnes, Marley, Goodall-Copestake, Convey & Linse, 2008 | ||

| 17. Ramazzottius oberhaeuseri (Doyère, 1840) | ANT, CAU, TOL [23] | Without material |

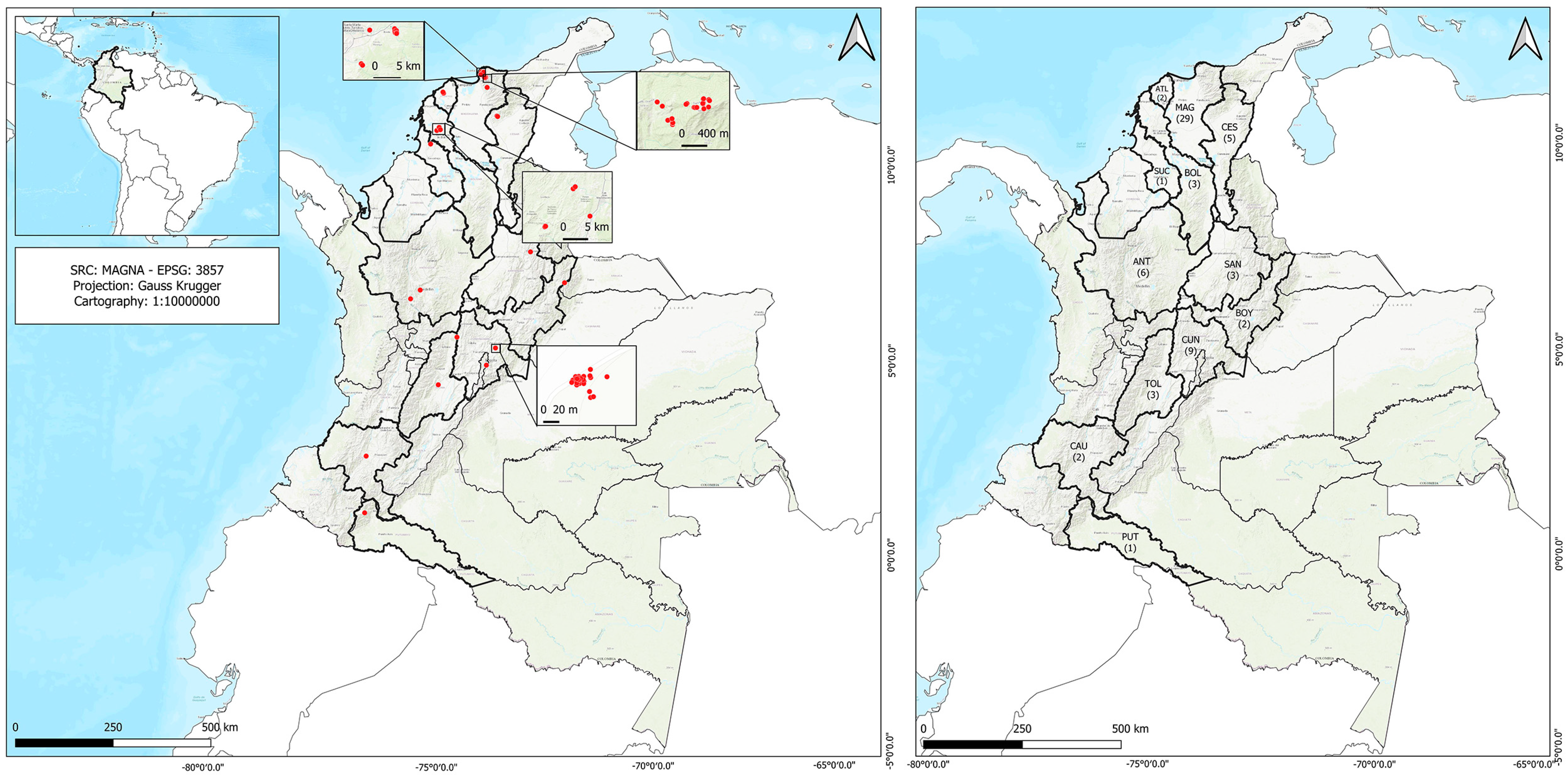

3.3. Distribution and Checklist

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guidetti, R.; Bertolani, R. Tardigrade taxonomy: An updated check list of the taxa and a list of characters for their identification. Zootaxa 2005, 845, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degma, P.; Guidetti, R. Notes to the current checklist of Tardigrada. Zootaxa 2007, 1579, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degma, P.; Guidetti, R. Actual Checklist of Tardigrada Species, 42nd ed.; University of Modena and Reggio Emilia: Modena, Italy, 2022; Available online: https://iris.unimore.it/retrieve/bf8e14a4-625f-4cdd-8100-347e5cbc5f63/Actual%20checklist%20of%20Tardigrada%2042th%20Edition%2009-01-23.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Ramazzotti, G.; Maucci, W. The Phylum Tardigrada, 3rd ed.; Istituto Italiano di Idrobiologia: Verbania, Italy, 1983; pp. 1–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, D.R. Current status of the Tardigrada: Evolution and ecology. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2002, 42, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdmann, W.; Kaczmarek, Ł. Tardigrades in space research past and future. Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 2017, 47, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebecchi, L.; Boschetti, C.; Nelson, D.R. Extreme-tolerance mechanisms in meiofaunal organisms: A case study with tardigrades, rotifers, and nematodes. Hydrobiologia 2020, 847, 2779–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, K.I. Tardigrades as a Potential Model Organism in Space Research. Astrobiology 2007, 7, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippov, A.E.; Gorb, S.N.; Popov, V.L. What can we learn from the “water bears” for the adhesion systems using in space applications? Facta Univ. Ser. Mech. Eng. 2015, 13, 241–247. [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto, T.; Kunieda, T. DNA protection protein, a novel mechanism of radiation tolerance: Lessons from tardigrades. Life 2017, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schill, R.O.; Mali, B.; Dandekar, T.; Schölzer, R.D.; Frohme, M. Molecular mechanisms of tolerance in tardigrades: New perspectives for preservation and stabilization of biological material. Biotechnol. Adv. 2009, 27, 348–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Martinez, S.; Ramirez, J.F.; Meese, E.K.; Childs, C.A.; Boothby, T.C. The tardigrade protein CAHS D interacts with, but does not retain, water in hydrated and desiccated systems. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, J.H.; Crowe, L. Preservation of mammalian cells—Learning nature’s tricks. Nat. biotechnol. 2000, 18, 145–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Moreno, S.; Ferris, H.; Guil, N. Role of tardigrades in the suppressive service of a soil food web. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2008, 124, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, S.J. Zoogeographic distribution of terrestrial/freshwater tardigrades from current literature. J. Nat. Hist. 1994, 28, 257–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, H. Terrestrial and freshwater Tardigrada of the Americas. Zootaxa 2013, 3747, 19–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaczmarek, Ł.; Michalczyk, Ł.; McInnes, S.J. Annotated zoogeography of non-marine Tardigrada. Part I: Central America. Zootaxa 2014, 3763, 1–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, Ł.; Michalczyk, Ł.; Mcinnes, S.J. Annotated zoogeography of non-marine Tardigrada. Part II: South America. Zootaxa 2015, 3923, 1–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, Ł.; Michalczyk, Ł.; Mcinnes, S.J. Annotated zoogeography of non-marine Tardigrada. Part III: North America and Greenland. Zootaxa 2016, 4203, 1–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisi, O.; Daza, A.; Londoño, R.; Quiroga, S. New species and records of tardigrades from a biological repository collection from the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2022, 94, e20201522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richters, F. Südamerikanische Tardigraden. Zool. Anz. 1911, 38, 273–277. [Google Scholar]

- Richters, F. Faune des Mousses: Tardigrades; C. Bulens: Bruxelles, Belgium, 1911; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Heinis, F. Die Moosfauna Columbiens. Mémoires De La Société Des Sci. Nat. De Neuchatel 1914, 5, 675–730. [Google Scholar]

- Du Bois-Raymond Marcus, E. Sobre tardígrados brasileiros. Zool. Mus. Hist. Nat. 1944, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, R.O.; Grigarick, A.A. Tardigrada from the Galápagos and Cocos islands. Proc. Calif. Acad. Sci. Fourth Ser. 1966, XXXIV, 315–328. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek, Ł.; Michalczyk, Ł.; Beasley, C.W. Milnesium katarzynae sp. nov., a new species of eutardigrade (Milnesiidae) from China. Zootaxa 2004, 743, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peluffo, J.; de Peluffo, M.C.M.; Rocha, A.M. Rediscovery of Echiniscus rufoviridis Du Bois-Raymond Marcus 1944 (Heterotardigrada, Echiniscidae): New contributions to the knowledge of its morphology, bioecology and distribution. Gayana 2002, 66, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, A.M.; Izaguirre, M.F.; de Peluffo, M.C.M.; Peluffo, J.R.; Casco, V.H. Ultrastructure of the cuticle of Echiniscus rufoviridis [Du Bois-Raymond Marcus, (1944) Heterotardigrada]. Acta Microsc. 2007, 16, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Fontoura, P.; Pilato, G.; Lisi, O. First record of Tardigrada from São Tomé (Gulf of Guinea, western Equatorial Africa) and description of Pseudechiniscus santomensis sp. nov. (Heterotardigrada: Echiniscidae). Zootaxa 2010, 2564, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, H.A.; Hinton, J.G. Terrestrial Tardigrada of the Island of Barbados in the West Indies, with the description of Milnesium barbadosense sp. n. (Eutardigrada: Apochela: Milnesiidae). Caribb. J. Sci. 2010, 46, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daza, A.; Caicedo, M.; Lisi, O.; Quiroga, S. New records of tardigrades from Colombia with the description of Paramacrobiotus sagani sp. nov. and Doryphoribius rosanae sp. nov. Zootaxa 2017, 4362, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisi, O.; Daza, A.; Londoño, R.; Quiroga, S. Echiniscidae from the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia, new records, and a new species of Bryodelphax Thulin, 1928 (Tardigrada). Zookeys 2017, 703, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pech, W.A.; Anguas-Escalante, A.; Cutz-Pool, L.Q.; Guidetti, R. Doryphoribius chetumalensis sp. nov. (Eutardigrada: Isohypsibiidae) a new tardigrade species discovered in an unusual habitat of urban areas of Mexico. Zootaxa 2017, 4344, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gąsiorek, P.; Stec, D.; Morek, W.; Michalczyk, Ł. Deceptive conservatism of claws: Distinct phyletic lineages concealed within Isohypsibioidea (Eutardigrada) revealed by molecular and morphological evidence. Contrib. Zool. 2019, 88, 78–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.R.; Adkins-Fletcher, R.; Guidetti, R.; Roszkowska, M.; Grobys, D.; Kaczmarek, Ł. Two new species of Tardigrada from moss cushions (Grimmia sp.) in a xerothermic habitat in northeast Tennessee (USA, North America), with the first identification of males in the genus Viridiscus. PeerJ 2020, 8, e10251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, A.; Camarda, D.; Ostertag, B.; Doma, I.; Meier, F.; Lisi, O. Actual State of Knowledge of the Limno-Terrestrial Tardigrade Fauna of the Republic of Argentina and New Genus Assignment for Viridiscus rufoviridis (du Bois Reymond Marcus, 1944). Diversity 2023, 15, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalczyk, Ł.; Kaczmarek, Ł. The Tardigrada Register: A comprehensive online data repository for tardigrade taxonomy. J. Limnol. 2013, 72, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinis, F. Die Moosfauna des Krakatau. Treubia 1928, 10, 231–244. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, E. Tardigrada. In Das Tierreich; Walter De Gruyter & Co.: Berlin, Germany, 1936; Volume 66, pp. 1–340. [Google Scholar]

- Melo, J.; Beltrán-Pardo, E.; Bernal, J.; Kaczmarek, Ł. New records of tardigrades from Colombia (Guatavita, Cundinamarca Department). Turk. J. Zool. 2015, 39, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastych, H. Tardigrada. In Checklisten der Fauna Österreichs No. 8, 31st ed.; Schuster, R., Ed.; Biosystematics and Ecology Series; Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften: Vienna, Austria, 2015; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Gąsiorek, P.; Stec, D.; Morek, W.; Michalczyk, Ł. An integrative redescription of Hypsibius dujardini (Doyère, 1840), the nominal taxon for Hypsibioidea (Tardigrada: Eutardigrada). Zootaxa 2018, 4415, 45–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stec, D.; Vecchi, M.; Calhim, S.; Michalczyk, Ł. New multilocus phylogeny reorganises the family Macrobiotidae (Eutardigrada) and unveils complex morphological evolution of the Macrobiotus hufelandi group. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2021, 160, 106987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel, J.O.; Sturm, H. Consideraciones sobre la Vegetación, la Productividad primaria neta y la Artropofauna asociada en regiones paramunas de la Cordillera Oriental. In Estudios Ecológicos del Páramo y del Bosque altoandino Cordillera Oriental de Colombia; Osejo, E.M., Sturm, H., Eds.; Guadalupe: Santafé de Bogotá, Colombia, 1994; pp. 47–70. [Google Scholar]

- Jerez, J.; Narváez, E. Tardígrados (Animalia: Tardigrada) de la Reserva El Diviso—Santander, Colombia. Biota Colomb. 2001, 2, 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Jerez, J.; Narváez, E.; Restrepo, R. Tardígrados en musgos de la Reserva el Diviso (Santander, Colombia). Rev. Colomb. Entomol. 2002, 28, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caicedo, M.; Londoño, R.; Quiroga, S. Catálogo taxonómico de los ositos de agua (Tardigrada) de la cuenca baja de los ríos Manzanares y Gaira, Santa Marta, Colombia. Bol. Cient. Mus. Hist. Nat. 2014, 18, 197–209. [Google Scholar]

- Lisi, O.; Londoño, R.; Quiroga, S. Tardigrada from a sub-Andean forest in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta (Colombia) with the description of Itaquascon pilatoi sp. nov. Zootaxa 2014, 3841, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Michalczyk, Ł.; Kaczmarek, Ł. Revision of the Echiniscus bigranulatus group with a description of a new species Echiniscus madonnae (Tardigrada: Heterotardigrada: Echiniscidae) from South America. Zootaxa 2006, 1154, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Rocha, C.M.C.; Gomes Júnior, E.L.; Santos, E.C.L. Brazilian limnoterrestrial tardigrades (Bilateria, Tardigrada): New occurrences and species checklist updates. Rev. Nord. Zoo. 2016, 10, 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Tumanov, D.V. Analysis of nonmorphometric morphological characters used in the taxonomy of the genus Pseudechiniscus (Tardigrada: Echiniscidae). Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2020, 188, 753–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londoño, R.; Daza, A.; Caicedo, M.; Quiroga, S.; Kaczmarek, Ł. The genus Milnesium (Eutardigrada: Milnesiidae) in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta (Colombia), with the description of Milnesium kogui sp. nov. Zootaxa 2015, 3955, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Degma, P.; Michalczyk, Ł.; Kaczmarek, Ł. Macrobiotus derkai, a new species of Tardigrada (Eutardigrada, Macrobiotidae, huziori group) from the Colombian Andes. Zootaxa 2008, 1731, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stec, D.; Roszkowska, M.; Kaczmarek, Ł.; Michalczyk, Ł. Paramacrobiotus lachowskae, a new species of Tardigrada from Colombia (Eutardigrada: Parachela: Macrobiotidae). N. Z. J. Zool. 2018, 45, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisi, O.; Daza, A.; Londoño, R.; Quiroga, S.; Pilato, G. Meplitumen aluna gen. nov., sp. nov. an interesting eutardigrade (Hypsibiidae, Itaquasconinae) from the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia. ZooKeys 2019, 865, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londoño, R.; Daza, A.; Lisi, O.; Quiroga, S. New species of waterbear Minibiotus pentannulatus (Tardigrada: Macrobiotidae) from Colombia. Rev. Mex. Biodivers. 2017, 88, 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisi, O.; Londoño, R.; Quiroga, S. Description of a new genus and species (Eutardigrada: Richtersiidae) from Colombia, with comments on the family Richtersiidae. Zootaxa 2020, 4822, 531–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gąsiorek, P.; Degma, P.; Michalczyk, Ł. Hiding in the Arctic and in mountains: A (dis)entangled classification of Claxtonia (Heterotardigrada: Echiniscidae). Zool. J. of Linn. Soc. 2023, XX, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morek, W.; Wałach, K.; Michalczyk, Ł. Rough backs: Taxonomic value of epicuticular sculpturing in the genus Milnesium Doyère, 1840 (Tardigrada: Apochela). Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quiroga, S.; Daza, A.; Londoño, R. Tardígrados del Centro de Colecciones Biológicas de la Universidad del Magdalena CBUMAG. Version 1.2. Universidad del Magdalena. Occurrence Dataset. Available online: https://ipt.biodiversidad.co/sib/resource?r=tardigrada_umagdalena (accessed on 18 November 2023).

- Pilato, G.; Lisi, O. Notes on some tardigrades from southern Mexico with description of three new species. Zootaxa 2006, 1236, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, Ł.; Michalczyk, Ł. A new species of Tardigrada (Eutardigrada: Milnesiidae): Milnesium krzysztofi from Costa Rica (Central America). N. Z. J. Zool. 2007, 34, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Simmons, J.E.; Muñoz-Saba, Y. Cuidado, Manejo y Conservación de las Colecciones Biológicas; Universidad Nacional de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2005; pp. 1–287. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Ministerio de Ambiente, Vivienda y Desarrollo Sostenible de Colombia. Decreto 309 de 2000. Available online: https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php?i=45528 (accessed on 13 October 2023).[Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Venencia-Sayas, D.; Londoño, R.; Daza, A.; Pertuz, L.; Marín-Muñoz, G.; Londoño-Mesa, M.H.; Lisi, O.; Camarda, D.; Quiroga, S. Tardigrades (Tardigrada) of Colombia: Historical Overview, Distribution, New Records, and an Updated Taxonomic Checklist. Diversity 2024, 16, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/d16010013

Venencia-Sayas D, Londoño R, Daza A, Pertuz L, Marín-Muñoz G, Londoño-Mesa MH, Lisi O, Camarda D, Quiroga S. Tardigrades (Tardigrada) of Colombia: Historical Overview, Distribution, New Records, and an Updated Taxonomic Checklist. Diversity. 2024; 16(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/d16010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleVenencia-Sayas, Dayanna, Rosana Londoño, Anisbeth Daza, Luciani Pertuz, Gabriel Marín-Muñoz, Mario H. Londoño-Mesa, Oscar Lisi, Daniele Camarda, and Sigmer Quiroga. 2024. "Tardigrades (Tardigrada) of Colombia: Historical Overview, Distribution, New Records, and an Updated Taxonomic Checklist" Diversity 16, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/d16010013

APA StyleVenencia-Sayas, D., Londoño, R., Daza, A., Pertuz, L., Marín-Muñoz, G., Londoño-Mesa, M. H., Lisi, O., Camarda, D., & Quiroga, S. (2024). Tardigrades (Tardigrada) of Colombia: Historical Overview, Distribution, New Records, and an Updated Taxonomic Checklist. Diversity, 16(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/d16010013