Abstract

A new pleurodiran turtle is described here. It is identified as attributable to Bothremydidae. The new taxon comes from an upper Maastrichtian (Upper Cretaceous) outcrop located in Southwestern Niger (in the Indamane Mount area, belonging to the Abalak Department of the Tahoua Region). Abalakemys chapmanae gen. et sp. nov. is identified by an almost complete large shell of about 65 cm in length. The new bothremydid turtle is recognized as a member of Bothremydodda, showing several autapomorphies (an exclusive ornamental pattern on the plate’s outer surface, covered by small depressions; small fourth pleural scutes, only anteromedially reaching the sixth pair of costal plates; and noticeably wedged posterior plastral lobe toward the posterior region), as well as a unique combination of characters for this clade. This turtle could belong to Nigeremydini, a poorly understood Maastrichtian to Paleocene lineage of Bothremydodda, which integrates large coastal taxa that inhabited the African Trans-Saharan seaway, and for which shell information is currently extremely limited.

1. Introduction

One of the two lineages of turtles grouped in the crown group Testudines is Pleurodira, with the lineage of Pan-Pleurodira being known from the Upper Jurassic [1,2,3]. In the current biodiversity setting, this group is much less diverse than the other lineage (i.e., Cryptodira), being, moreover, restricted to freshwater taxa, exclusively inhabiting intertropical regions in the southern continents [4]. However, the fossil record, especially that of the Cretaceous and Paleogene, shows that the lineage of Pleurodira was also very abundant and diverse in the past, with a markedly greater range of paleobiogeographic distribution, as well as with adaptations to a greater range of environments. One of the most successful groups of the crown group Pleurodira was Bothremydidae, known from the Early Cretaceous to the Miocene [5,6]. It is a lineage of Gondwanan origin and has been recognized on several continents in both the Southern and Northern Hemispheres [7,8].

The pleurodiran fossil record compiled from the study of specimens found in Cretaceous sites of Niger is highly relevant to understanding the evolutionary history and diversity of this lineage of turtles. The remains from two different Cretaceous epochs stand out. On the one hand, abundant remains of turtles are recognized in the Aptian (Early Cretaceous) fauna of the Gadoufaoua area (Agadez Region), all of them belonging to Pleurodira. A member of Araripemydidae is identified there, i.e., Taquetochelys decorata Broin, 1980 [9], and is the only representative of this lineage currently recognized as valid for the complete African record (a continent where Araripemydidae is identified from the Barremian, or possibly before, to the lower Cenomanian, with several unnamed representatives being present), with araripemydids also being recognized in South America, where this clade was defined [10]. Two other pleurodiran taxa, Teneremys lapparenti Broin, 1980 [9], and Francemys gadoufaouaensis Pérez-García, 2019 [7], were also defined in the Gadoufaoua area. Both are identified as members of Pelomedusoides, probably closely related to the crown group Podocnemidoidea [7]. The other Cretaceous epoch with a relatively high diversity of pleurodiran turtles is the upper Maastrichtian (Upper Cretaceous) record of the Tahoua Region, where several members of the lineage of Pelomedusoides Podocnemidoidea have been identified. A new member of the lineage of Podocnemididae Erymnochelyinae, Ragechelus sahelica Lapparent de Broin, Chirio, and Bour, 2020 [11], was recently defined by a single skull found there. It is a taxon of medium size, given that its maximum shell length has been estimated at about 30 cm (on the basis of a damaged carapace found near the skull corresponding to its holotype and identified in the paper where the taxon was described as possibly belonging to the same specimen but not collected; see Ref. [11]). However, the Podocnemidoidea lineage that is recognized as the most abundant and diverse in that region is not Podocnemididae but Bothremydidae. Two large bothremydid forms belonging to Nigeremydini (sensu [12]; see Discussion), described by two skulls coming from that area, are currently considered valid: Nigeremys gigantea (Bergounioux and Crouzel, 1968) [13] and Ilatardia cetiotesta Pérez-García, 2019 [14,15]. However, the recorded diversity of Bothremydidae in that region has been recognized as greater. In this sense, the presence of a relatively long carapace (i.e., shell length of about 65 cm), hitherto unpublished, deposited in the Natural History Museum of London, has been cited, being proposed as attributable to a probable new member of Bothremydidae [11,16].

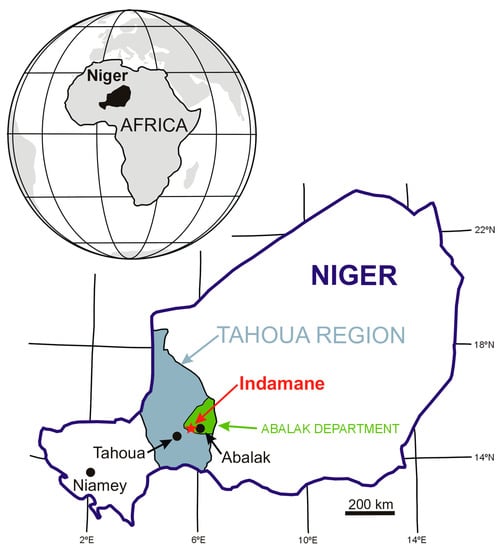

The objective of this work is the analysis of the aforementioned large shell from the upper Maastrichtian of the Tahoua Region (Southwestern Niger). Specifically, it comes from the area of the Indamane Mount, located in the Abalak Department (Figure 1). As a result of the study carried out here, a new member of Pleurodira Bothremydidae, from the upper Maastrichtian of Niger, is described. Its phylogenetic position is discussed, and detailed comparisons with closely related forms, especially with that of Bothremydodda, are provided.

Figure 1.

Geographical location of the paleontological area of the Indamane Mount (Abalak Department, Tahoua Region, Southwestern Niger), the type locality of the upper Maastrichtian (Upper Cretaceous) pleurodiran bothremydid turtle Abalakemys chapmanae gen. et sp. nov. Modified from Ref. [14].

Institutional Abbreviations: NHMUK, Natural History Museum, London, United Kingdom.

2. Materials and Methods

The anatomical and systematic study of a relatively complete and articulated shell of a turtle from the Upper Cretaceous (upper Maastrichtian of the Farin-Doutchi Formation, in the Iullemmeden Basin) of Southwestern Niger (Indamane Mount area, Abalak Department, Tahoua Region) was performed here. The specimen, collected by David Ward in December 1990, is deposited in the vertebrate paleontology collection (specifically in the reptile collection, in the section in which the fossil turtles are housed) of the Natural History Museum of London (United Kingdom). It is recognized under the collection number NHMUK R37356.

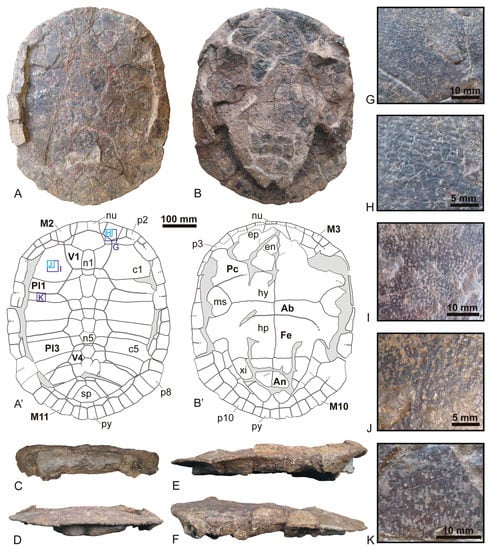

After a firsthand evaluation of the specimen, the carapace is described in detail. It is represented by photographs of the specimen in all six views, i.e., dorsal, ventral, anterior, posterior, right lateral, and left lateral views (Figure 2A–F). Furthermore, details of the outer surface of various regions of the carapace are also included in the same figure in order to show its ornamental pattern (see Figure 2G–K). Additionally, schematic drawings of the shell are included in the same figure in the dorsal and ventral views. The complete margins of the plates and scutes are represented in these drawings, as well as broken edges (see Figure 2A′,B′, in which the complete margins of the plates are represented by continuous black lines, the broken margins of the plates by dotted black lines, and the margins of the scutes by thicker gray lines).

Figure 2.

NHMUK R37356, shell corresponding to the holotype of the pleurodiran bothremydid turtle Abalakemys chapmanae gen. et sp. nov., from the upper Maastrichtian (Late Cretaceous) of the Indamane Mount area (Abalak Department, Tahoua Region, Southwestern Niger), in dorsal (A,A’), ventral (B,B’), anterior (C), posterior (D), right lateral (E), and left lateral (F) views. (G–K) details of the outer surface of the carapace, whose precise location is shown in (A′). Abbreviations for the plates (lowercase and normal font): c, costal; en, entoplastron; ep, epiplastron; hp, hypoplastron; hy, hyoplastron; ms, mesoplastron; n, neural; nu, nuchal; p, peripheral; py, pygal; sp, suprapygal; xi, xiphiplastron. Abbreviations for the scutes (capitalized and bold): Ab, abdominal; An, anal; Fe, femoral; M, marginal; Pc, pectoral; Pl, pleural; V, vertebral. (A′,B′) represent schematic drawings of the specimen, in which the dotted lines indicate broken edges, continuous black lines correspond to the margins of the plates, the borders of the scutes are represented by thicker gray lines, and the gray surfaces correspond to sediment.

The morphological characters recognized in the shell NHMUK R37356 were analyzed in detail, which allowed for the systematic attribution of the specimen. It is recognized as attributable to a new taxon of Bothremydodda, for which a diagnosis is proposed, which includes both autapomorphies and a unique character combination within this lineage.

3. Systematic Paleontology

Testudines Batsch, 1788 [17];

Pleurodira Cope, 1864 [18];

Pelomedusoides Cope, 1868 [19];

Podocnemidoidea Cope, 1868 [19];

Bothremydidae Baur, 1891 [20];

Bothremydodda Gaffney, Tong and Meylan, 2006 [1];

Abalakemys chapmanae gen. et sp. nov.

(Figure 2).

Holotype. NHMUK R37356, an almost complete and articulated shell, lacking the most anterior area of the plastron (Figure 2).

Etymology. The generic name is composed of Abalak–, i.e., the department from which the holotype comes, and –emys (Greek), referring to turtle. The specific epithet is named in honor of Dr. Sandra Chapman, the former curator of the Natural History Museum (MHMUK) vertebrate paleontology collection where the holotype of this new species is deposited.

Type locality and horizon. Indamane Mount area (also called Igdaman or In Dama Mount), Abalak Department, Tahoua Region, Southwestern Niger (Figure 1). Iullemmeden Basin. Top of bed 19 of Ref. [21], Farin-Doutchi Formation (“Mosasaurus Shales”), Upper Cretaceous, upper Maastrichtian (see Ref. [11] and references therein).

Diagnosis. Member of Bothremydodda showing the following autapomorphies: outer surface of the shell covered by small depressions of less than one millimeter in diameter, locally generating parallel ridges; small fourth pleural scutes, only anteromedially reaching the sixth costals; markedly wedged posterior plastral lobe toward the posterior region. This taxon displays the following unique character combination within Bothremydodda: carapace length reaching at least 65 cm; subrounded carapace; low shell; absence of a nuchal notch, with the anterior margin of the carapace being convex; slightly wider than long nuchal, with a wide anterior margin, equivalent to two-thirds of the plate maximum width; seven neurals, allowing the last two pairs of costals to reach the axial plane; the first pair of costals almost twice as long as the second pair; wider than long suprapygal; as long as wide first pair of peripherals and pygal; second vertebral scute being the widest of the vertebral series; wider than long second and third vertebrals; subpentagonal first vertebral; hexagonal second to fourth vertebrals, with lateral vertices close to 90° and showing lateral expansion; the first pair of marginals overlapping more than half the lateral margins of the nuchal plat; deep anal notch; pectoral-abdominal sulcus medially closer to the entoplastron than to the hypoplastra; pectoral scutes contacting the anterior margin of the mesoplastra; short distance between the hyoplastra and the femoral scutes.

Description. The length of the shell studied here is about 65 cm (Figure 2A–F). It is interpreted as subrounded, being slightly longer than wide (the maximum width probably represents 90% of its maximum length), but it shows a slight taphonomic lateral compression, so the bridge peripherals are not preserved in articulation with the costal plates. The maximum width of the carapace was probably located at the level of the sixth pair of peripherals. Although the specimen is dorsoventrally flattened, it is interpreted as a low shell based on the morphology of all carapace plates, as well as considering the articulation between many of them (including those of the medial area) and the absence of fractures on the central area. The outer surface of the shell is covered by small depressions (each of them less than one millimeter in diameter), which are partially aligned in some regions, generating a pattern of parallel ridges (Figure 2G–K). In addition, discontinuous dichotomous grooves, which generate polygons of irregular morphology and of several millimeters in length, are recognized.

The nuchal plate is slightly wider than long (Figure 2A). It shows a wide anterior margin, with the maximum width of the plate being one and a half times that of that margin. This taxon lacks a nuchal notch. Nevertheless, the anterior margin of the nuchal plate is convex. The neural series is composed of seven plates. The first neural is subrectangular, being twice as long as wide. The second to sixth neurals are hexagonal. Among them, the first four have shorter anterolateral margins than posterolateral margins. However, both margins are identified as equidimensional in the sixth neural. Due to its preservation, the morphology of the seventh neural cannot be fully recognized, although it is interpreted as pentagonal. The last pairs of costals (the eighth and probably the seventh) show medial contact. The first pair of costals is almost twice as long as the second pair. The suprapygal is subpentagonal, being wider than long. Both the first pair of peripherals and the pygal plate are as long as wide.

This shell of the new taxon lacks a cervical scute (Figure 2A). The widest scute of the vertebral series is the second. The first one is subpentagonal. The second to fourth vertebrals are hexagonal, with lateral vertices close to 90° and showing lateral expansion. The second and third vertebrals are wider than long, but both dimensions are subequal in the fourth. The fifth vertebral and the pleural scutes show a relatively long overlap on the peripheral series. The fourth pair of pleurals is markedly reduced, since the third pair overlaps the seventh costals. The first pair of marginals overlaps more than half the length of the lateral margins of the nuchal plate.

Due to the preservation of the specimen, the morphology of the anterior margin of the anterior plastral lobe is unknown (Figure 2B), and, as a result, several of the plates and scutes in this lobe cannot be characterized. The plastral lobes are identified as relatively wide, with the posterior being wider than long, and this condition is also interpreted for the anterior one. The specimen shows a pair of relatively small mesoplastra, laterally located. The posterior plastral lobe is markedly wedged toward the posterior region. The anal notch is well developed and observed to be deep. The axillary buttresses reach the middle length of the third pair of peripherals, and the inguinal buttresses show a very long contact with the seventh one.

Medially, the pectoroabdominal sulcus is located closer to the entoplastron than to the hypoplastra (Figure 2B). The pectoral scutes contact the anterior margin of the mesoplastra. The distance between the femoral scutes and the hyoplastra is short. The anal scutes are restricted to the xiphiplastra, showing a relatively large distance from the hypoplastra.

4. Results

The specimen studied here (i.e., the almost complete and articulated shell NHMUK R37356) displays a combination of shell characters that allows its identification as a pleurodiran turtle, attributable to the lineage of Bothremydidae: low and subrounded shell; long first neural and first pair of costals, with this pair of costals being about twice longer than the second pair; relatively short neural series composed of fewer than eight plates, allowing the medial contact of the posterior costals; axillary buttresses showing a long contact with the third pair of peripherals, and inguinal buttresses reaching the fifth costals; relatively small mesoplastra, laterally located; and the absence of a cervical scute [1,7,22,23,24,25]. Therefore, its attribution to other ornate-shelled pleurodiran lineages recognized in the African Cretaceous record (e.g., Araripemydidae) is excluded.

Within Bothremydidae, the specimen studied here cannot be identified as a member of Kurmademydini based on the absence of the granulated polygons on the shell’s outer surface recognized for the clade; of a long distance between the pectoral scutes and the mesoplastra; and of a remarkably long bridge relative to the plastral lobes [26]. Its attribution to Cearachelyini can also be excluded considering characters such as, among others, the absence of a hexagonal first neural, with short posterolateral sides, as well as the presence of a hexagonal second neural, in contact with the first pair of costal plates [1]. However, NHMUK R37356 is clearly recognized as a representative of the clade Bothremydodda based on the presence of a wide anterior plastral lobe. In fact, as happens with representatives of this lineage, this lobe is interpreted as relatively short, with its anterior margin probably not exceeding that of the carapace [1,24,26].

5. Discussion

Gaffney et al. (2006) [1] recognized two lineages for Bothremydodda, i.e., Bothremydini and Taphrosphyini. For these authors, this second lineage integrated members of Nigeremydina (exclusively including two African Upper Cretaceous taxa: Nigeremys gigantea, from the Maastrichtian of Niger, and Arenila krebsi Lapparent de Broin and Werner, 1998 [27], from the Maastrichtian of Egypt) and those of the much more diverse Taphrosphyina. However, the phylogenetic positions of Azabbaremys moragjonesi Gaffney, Moody, and Walker, 2001 [28], and Acleistochelys maliensis Gaffney, Roberts, Sissoko, Bouaré, Tapanila, and O’Leary, 2007 [29] (both species corresponding to bothremydids from the Paleocene of Mali), although proposed as constituting a basal node within Taphrosphyina, were not confirmed for some of the phylogenetic hypotheses presented in that publication (in which these species were obtained in a polytomy that also included the Nigeremydina node and that grouped the other representatives of Taphrosphyina; see Figure 289 in Ref. [1]). A new form closely related to Nigeremys gigantea, i.e., Ilatardia cetiotesta, also from the Maastrichtian of Niger, was subsequently defined [14]. Lapparent de Broin and Prasad (2020) [12] (see also Ref. [5]) proposed that Taphrosphyini should be restricted to the clade grouping those taxa that Gaffney et al. (2006) [1] attributed to Taphrosphyina. In this sense, the other representatives of the clade Taphrosphyini sensu Gaffney et al. (2006) [1] (i.e., Nigeremys gigantea, Arenila krebsi, Azabbaremys moragjonesi, Acleistochelys maliensis), but also the recently described Ilatardia cetiotesta and the problematic ‘Sokotochelys umarumohammedi’ Halstead, 1979 [30], and ‘Sokotochelys lawanbungudui’ Halstead, 1979 [30], from the Maastrichtian of Nigeria (currently identified as a nomina dubia; see Refs. [1,14]), would be grouped in the clade Nigeremydini. Following this proposal, Nigeremydini groups the large coastal bothremydids that inhabited the Maastrichtian and the Paleocene in the Trans-Saharan seaway, which connected the North African Tethys and the Atlantic Guinean Gulf [11,12].

In this context, the turtle analyzed here cannot be identified as attributable to Taphrosphyini (sensu [12]), as it does not share with the members of this lineage characters such as the presence of deep grooves generating an ornamental pattern formed by well-developed irregular raised polygons; a very elongated first pair of costal plates, more than twice as long as the second pair; a quadrangular first pair of marginal scutes; and a semicircular anal notch [1,31,32]. It cannot be attributed to the Bothremydini clade either considering, among other characters, that the outer surface of its shell is covered by a strong texture, contrasting with the fine forking and irregular vascular grooves that characterize this lineage [1,26]. The size of the specimen studied here is compatible with those of large representatives of Nigeremydini. Its attribution to Nigeremydini is further supported on the basis of the area it inhabited, as well as its consistency with the stratigraphic context recognized for this lineage, since it was found in a Maastrichtian outcrop off the coast of the aforementioned inner Trans-Saharan African sea and, specifically, in a region (the Tahoua Region) where several members of Nigeremydini have been identified (i.e., Nigeremys gigantea, from an upper Maastrichtian outcrop in the Mount In Tahout area in the Abalak Department, and Ilatardia cetiotesta, from an upper Maastrichtian outcrop in the Mount Ilatarda area, also in the Abalak Department; both come from slightly older stratigraphical levels than that in which the new taxon described here was found; see Ref. [11]). Nigeremydini has been diagnosed by a combination of exclusively cranial characters. In this sense, the probable attribution to this lineage of forms such as the recently described Sindhochelys ragei Lapparent de Broin, Métais, Bartolini, Brohi, Lashari, Marivaux, Merle, Warar, and Solangi, 2021 [5], exclusively identified by a shell from the early Paleocene of Southern Pakistan and corresponding to a large member of Bothremydodda not attributable to either Taphrosphyini or Bothremydini, has not been confirmed.

The ornamental pattern observed on the outer surface of the plates of the specimen analyzed here, NHMUK R37356, is not shared with any other member of Bothremydidae so far defined. A relatively complete plastron is identified among the material found in the type locality of the recently described member of Nigeremydini Ilatardia cetiotesta (i.e., in the Mount Ilatarda area of the Abalak Department), which is also deposited in the NHMUK collection of fossil turtles. It corresponds to a larger individual than the holotype of the taxon defined here (being more than 15% longer in length) and is not attributable to it considering, in addition to the absence of its exclusive ornamental pattern, characters such as, among others, its short but wide anal notch, the absence of a markedly wedged posterior plastral lobe toward the posterior region, or the presence of proportionally larger mesoplastra. The ornamental pattern indicated by Lapparent de Broin et al. (2020) [11] for the different plates found in the type locality of Nigeremys gigantea (i.e., the Mount In Tahout area), recognized as attributable to various undefined forms, is not compatible with that of the specimen analyzed here. An ornamental pattern similar to that described for the shell of the new taxon would be expected for its outer cranial surface. Although the shell material, indisputably attributable to any described representative of Nigeremydini, was not hitherto known (all of these taxa having been defined by the skull), a partial carapace from a Maastrichtian outcrop of Egypt was identified as cf. Arenila (see Ref. [27]). Its neural series is shorter than that of the taxon analyzed here, being composed of six plates, and its cordiform morphology also represents another notable difference relative to it. The specimen analyzed here shows numerous differences when it is compared with Sindhochelys ragei, with this taxon also known by the shell (see Ref. [5]). Thus, the species from Pakistan is not compatible with the taxon from the Indamane Mount area considering characters such as its wider pygal, its subrectangular first to third vertebral scutes, the absence of overlapping of the third pair of vertebrals on the seventh costal plates, the absence of a markedly wedged posterior plastral lobe toward the posterior region, and the longer distance between the pectoral-abdominal sulcus and the entoplastron.

Therefore, the bothremydid shell analyzed here cannot be identified as belonging to any taxon defined up to now. It is attributed to a new member of Bothremydodda, Abalakemys chapmanae gen. et sp. nov., probably corresponding to the Nigeremydini clade.

6. Conclusions

The almost complete shell of a relatively large pleurodiran turtle (shell length about 65 cm), from the Upper Cretaceous fossil record of Niger (West Africa), is presented here. This fossil, NHMUK R37356, comes from the Indamane Mount area, located in the Abalak Department of the Tahoua Region, located in Southwestern Niger. Specifically, the specimen was found in an upper Maastrichtian outcrop of the Farin-Doutchi Formation (also recognized as the “Mosasaurus Shales”) in the Iullemmeden Basin. It is identified as attributable to a pleurodiran bothremydid turtle, belonging to the Bothremydodda clade. The shell analyzed here cannot be recognized as belonging to any taxon defined up to now, since it shows several autapomorphies. These are the development of an exclusive ornamental pattern on the outer surface of the plates, covered by small depressions; the presence of small fourth pleural scutes, only anteromedially reaching the sixth pair of costal plates; and a noticeably wedged posterior plastral lobe toward the posterior region. In addition, a unique combination of shell characters within this lineage is recognized in this specimen, including a carapace length reaching at least 65 cm; a subrounded carapace; a low shell; the absence of a nuchal notch, with the anterior carapace margin being convex; slightly wider than long nuchal, with a wide nuchal anterior margin, equivalent to two-thirds of the plate’s maximum width; seven neurals, allowing the last two pairs of costal plates to reach the axial plane; first pair of costals almost twice as long as the second; wider than long suprapygal; as long as wide first pair of peripherals and pygal; second vertebral scute being the widest of the vertebral series; wider than long second and third vertebrals; subpentagonal first vertebral; hexagonal second to fourth vertebrals, with vertices close to 90º and showing lateral expansion; first pair of marginal scutes overlapping more than half the nuchal lateral margins; a deep anal notch; pectoral-abdominal sulcus medially closer to the entoplastron than to the hypoplastra; pectoral scutes contacting the mesoplastra anterior margin; and a short distance between the hyoplastra and the femoral scutes. Thus, a new taxon, Abalakemys chapmanae gen. et sp. nov., is defined here based on the specimen NHMUK R37356.

Two members of the lineage of Bothremydodda Nigeremydini were previously identified in the Tahoua Region: Nigeremys gigantea, from an upper Maastrichtian outcrop in the area of Mount In Tahout, and Ilatardia cetiotesta, from an upper Maastrichtian outcrop in the area of Mount Ilatarda. Both outcrops are located in the Abalak Department, from which the specimen studied here comes, but corresponding to slightly older stratigraphical levels. Nigeremydini groups Maastrichtian and Paleocene large coastal bothremydids that inhabited the African Trans-Saharan seaway. Information on the shell of the members of this lineage was extremely limited. For this reason, although the specimen analyzed here belongs to Bothremydodda and shows a size compatible with that of representatives of Nigeremydini, coming from an outcrop located in the stratigraphic and geographic range of distribution of this lineage, its probable attribution to it should be confirmed by future finds of, preferably associated, shells and skulls.

Funding

This research has been funded by the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (PID2019-111488RB-I00) and by the Synthesys project GB-TAF-4187, financed by the 7th Framework Programme for the European Union Research (FP7).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks S. Chapman for her kind administrative management and support for access, during several research stays, to the NHMUK turtle collection, as well as for the information provided on several specimens, and the editor Helen Wei and three anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Gaffney, E.S.; Tong, H.; Meylan, P.A. Evolution of the side-necked turtles: The families Bothremydidae, Euraxemydidae, and Araripemydidae. B Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 2006, 300, 1–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-García, A. The Iberian fossil record of turtles: An update. J. Iber. Geol. 2017, 43, 155–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, W.G.; Anquetin, J.; Cadena, E.A.; Claude, J.; Danilov, I.G.; Evers, S.W.; Ferreira, G.S.; Gentry, A.D.; Georgalis, G.J.; Lyson, T.R.; et al. A nomenclature for fossil and living turtles using phylogenetically defined clade names. Swiss J. Palaeontol. 2021, 140, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodin, A.G.J.; Iverson, J.B.; Bour, R.; Fritz, U.; Georges, A.; Shaffer, H.B.; van Dijk, P.P. Turtles of the World: Annotated Checklist and Atlas of Taxonomy, Synonymy, Distribution, and Conservation Status (9th Ed.). Chelonian Res. Monogr. 2021, 8, 1–472. [Google Scholar]

- De Lapparent de Broin, F.; Métais, G.; Bartolini, A.; Brohi, I.A.; Lashari, R.A.; Marivaux, L.; Merle, D.; Warar, M.A.; Solangi, S.H. First report of a bothremydid turtle, Sindhochelys ragei n. gen., n. sp., from the early Paleocene of Pakistan, systematic and palaeobiogeographic implications. Geodiversitas 2021, 43, 1341–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, P.S.R.; Gallo, V.; Ramos, R.R.C.; Antonioli, L. Atolchelys lepida, a new side-necked turtle from the Early Cretaceous of Brazil and the age of crown Pleurodira. Biol. Lett. 2014, 10, 20140290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-García, A. The African Aptian Francemys gadoufaouaensis gen. et sp. nov.: New data on the early diversification of Pelomedusoides (Testudines, Pleurodira) in northern Gondwana. Cretac. Res. 2019, 102, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lapparent de Broin, F. African chelonians from the Jurassic to the Present: Phases of development and preliminary catalogue of the fossil record. Palaeontol. Afr. 2000, 36, 43–82. [Google Scholar]

- De Lapparent de Broin, F. Les Tortues de Gadoufaoua (Aptien du Niger); aperçu sur la paléobiogéographie des Pelomedusidae (Pleurodira). Mem. Soc. Geol. France 1980, 139, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-García, A. Identification of the Lower Cretaceous pleurodiran turtle Taquetochelys decorata as the only African araripemydid species. C. R. Palevol. 2019, 18, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lapparent de Broin, F.; Chirio, L.; Bour, R. The oldest erymnochelyine turtle skull, Ragechelus sahelica n. gen., n. sp., from the Iullemmeden basin, Upper Cretaceous of Africa, and the associated fauna in its geographical and geological context. Geodiversitas 2020, 42, 455–484. [Google Scholar]

- De Lapparent de Broin, F.; Prasad, G.V.R. Chelonian Pelomedusoides remains from the Late Cretaceous of Upparhatti (Southwestern India): Systematics and Palaeobiogeographical implications. In Biological Consequences of Plate Tectonics; Prasad, G.V.R., Ed.; Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology Series; Springer Science & Business Media Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 123–180. [Google Scholar]

- Bergounioux, F.-M.; Crouzel, F. Deux tortues fossiles d’Afrique. Bull. Soc. Hist. Nat. Toulouse 1968, 104, 179–186. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-García, A. A new member of Taphrosphyini (Pleurodira, Bothremydidae) from the Maastrichtian of Niger. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2019, 158, 103548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lapparent de Broin, F. Contribution à l’étude des Chéloniens. Chéloniens continentaux du Crétacé et du Tertiaire de France. Mém. Mus. Natl. Hist. Nat. 1977, 38, 1–366. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-García, A.; Chapman, S.D. Implications on the uppermost Cretaceous diversity of Pleurodira in Southwest Niger based on the finding of the first almost complete shell. In Abstract Book of the XVII Annual Meeting of the European Association of Vertebrate Paleontologists; Akademischen Buchhandlung: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; p. 87. [Google Scholar]

- Batsch, G.C. Versuch Einer Anleitung, zur Kenntniß und Geschichte der Thiere und Mineralien; Akademischen Buchhandlung: Jena, Germany, 1788; 528p. [Google Scholar]

- Cope, E.D. On the limits and relations of the Raniformes. Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Phila. 1864, 16, 181–183. [Google Scholar]

- Cope, E.D. On the origin of genera. Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Phila. 1868, 20, 242–300. [Google Scholar]

- Baur, G. Notes on some little known American fossil tortoises. Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Phila. 1891, 43, 411–430. [Google Scholar]

- Moody, R.T.J.; Sutcliffe, P.J.C. The Cretaceous deposits of the Iullemmeden Basin of Niger, central West Africa. Cretac. Res. 1991, 12, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lapparent de Broin, F.; Murelaga, X. Turtles from the Upper Cretaceous of Laño (Iberian Peninsula). Est. Mus. Cienc. Nat. Álava 1999, 14, 135–211. [Google Scholar]

- Cadena, E.A.; Bloch, J.I.; Jaramillo, C.A. New bothremydid turtle (Testudines, Pleurodira) from the Paleocene of North-Eastern Colombia. J. Paleontol. 2012, 86, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-García, A. A new turtle taxon (Podocnemidoidea, Bothremydidae) reveals the oldest known dispersal event of the crown Pleurodira from Gondwana to Laurasia. J. Syst. Palaeont. 2016, 15, 709–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-García, A. New insights on the only bothremydid turtle (Pleurodira) identified in the British record: Palemys bowerbankii new combination. Palaeontol. Electron 2018, 21.2.28A, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-García, A. A new bothremydid turtle (Pleurodira) from the Upper Cretaceous (Cenomanian) of Madagascar. Cretac. Res. 2021, 118, 104645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lapparent de Broin, F.; Werner, C. New Late Cretaceous turtles from the Western Desert, Egypt. Ann. Paleontol. 1998, 84, 131–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, E.S.; Moody, R.T.J.; Walker, C.A. Azabbaremys, a new side-necked turtle (Pelomedusoides: Bothremydidae) from the Paleocene of Mali. Am. Mus. Novit. 2001, 3320, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, E.S.; Roberts, E.; Sissoko, F.; Bouaré, M.L.; Tapanila, L.; O’Leary, M.A. Acleistochelys, a New Side-Necked Turtle (Pelomedusoides: Bothremydidae) from the Paleocene of Mali. Am. Mus. Novit. 2007, 3549, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halstead, L.B. A taxonomic note on new fossil turtles. Nig. Field Monog. 1979, 1, 48–49. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-García, A. New genera of Taphrosphyina (Pleurodira, Bothremydidae) for the French Maastrichtian ‘Tretosternum’ ambiguum and the Peruvian Ypresian ‘Podocnemis’ olssoni. Hist. Biol. 2020, 32, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-García, A.; Mees, F.; Smith, T. Shell anatomy of the African Paleocene bothremydid turtle Taphrosphys congolensis and systematic implications within Taphrosphyini. Hist. Biol. 2020, 32, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).