Abstract

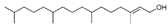

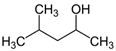

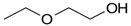

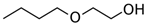

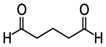

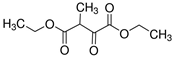

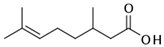

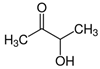

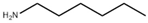

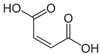

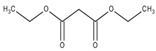

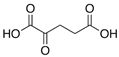

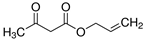

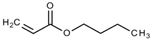

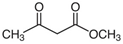

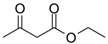

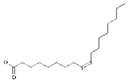

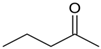

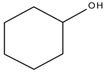

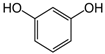

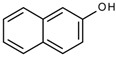

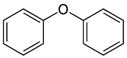

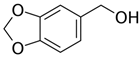

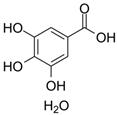

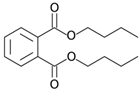

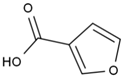

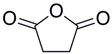

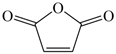

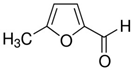

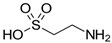

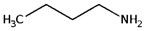

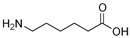

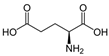

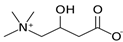

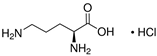

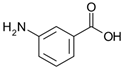

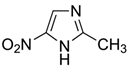

Many chemically synthesized xenobiotics can significantly inhibit the vitality of parasitic nematodes. However, there is yet too little research on the toxicity of such contaminating compounds toward nematodes. Compounds that are present in plants are able to inhibit the vitality of parasitic organisms as well. According to the results of our laboratory studies of toxicity, the following xenobiotics caused no decrease in the vitality of the larvae of Strongyloides papillosus and Haemonchus contortus: methanol, propan-2-ol, propylene glycol-1,2, octadecanol-1, 4-methyl-2-pen-tanol, 2-ethoxyethanol, butyl glycol, 2-pentanone, cyclopentanol, ortho-dimethylbenzene, dibutyl phthalate, succinic anhydride, 2-methylfuran, 2-methyl-5-nitroimidazole. Strong toxicity towards the nematode larvae was exerted by glutaraldehyde, 1,4-diethyl 2-methyl-3-oxobutanedioate, hexylamine, diethyl malonate, allyl acetoacetate, tert butyl carboxylic acid, butyl acrylate, 3-methyl-2-butanone, isobutyraldehyde, methyl acetoacetate, ethyl acetoacetate, ethyl pyruvate, 3-methylbutanal, cyclohexanol, cyclooctanone, phenol, pyrocatechin, resorcinol, naphthol-2, phenyl ether, piperonyl alcohol, 3-furoic acid, maleic anhydrid, 5-methylfurfural, thioacetic acid, butan-1-amine, dimethylformamide, 1-phenylethan-1-amine, 3-aminobenzoic acid. Widespread natural compounds (phytol, 3-hydroxy-2-butanone, maleic acid, oleic acid, hydroquinone, gallic acid-1-hydrate, taurine, 6-aminocaproic acid, glutamic acid, carnitine, ornithine monohydrochloride) had no negative effect on the larvae of S. papillosus and H. contortus. A powerful decrease in the vitality of nematode larvae was produced by 3,7-dimethyl-6-octenoic acid, isovaleric acid, glycolic acid, 2-oxopentanedioic acid, 2-methylbutanoic acid, anisole, 4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzyl alcohol, furfuryl alcohol. The results of our studies allow us to consider 28 of the 62 compounds we studied as promising for further research on anti-nematode activity in manufacturing conditions.

1. Introduction

Various groups of organic compounds are abundant in nature and can be active against the development of parasitic nematodes during their migration in the soil and on plants. Nematodes should have become adapted to many of these compounds over millions of years of their evolution [1,2,3]. Xenobiotics are compounds that were absent in the natural ecosystems prior to the impact of man and which have begun to actively contaminate ecosystems in the last few centuries [4]. They include thousands of various compounds used in human and veterinary medicine, food, chemical, paint, varnish industries, household, construction, etc. Such compounds can locally contaminate natural ecosystems, decreasing the vitality of nematode larvae in small areas of waste accumulation [5,6,7]. Many of those compounds concentrate around urban agglomerations: they end up in landfills of solid municipal wastes after traveling with wastewater from light and chemical industries, after being dumped as food wastes, and discharged from sewers [8,9].

Therefore, it is expected that thousands of various organic contaminants (mainly xenobiotics) should have different effects on soil nematodes. Our previous studies determined that their toxicity to nematode larvae varies broadly: LC50 ranges from fractions of a milligram per liter to several grams per liter [10,11]. Many of those compounds have no effect on the vitality of nematodes, despite the fact that those organisms most likely had never encountered them over millions of years of their evolution [6].

Nematodes perceive the environment as gradients of concentrations of chemical signals that either attract or repel them. At high concentrations, repellents at first repel or poison them, later causing their death [12]. Larvae of parasitic nematodes (for example, species of Haemonchus, Trichostrongylus, and Oesophagostomum genera) spend months traveling in the upper soil horizons, ascending plants at the height of 10–50 cm above the soil surface, waiting for ruminants to eat these plants [13]. Together with rainwater, some larvae become introduced into the shallow water of water bodies (rivers, lakes, ponds) and end up in the organisms of ruminants after they drink infested water. During those life stages, nematodes are most susceptible to the influence of chemical signals—gradients of concentrations of volatile compounds generated by plants, products of life of animals, and also chemically synthesized xenobiotics contaminating the environment [14,15].

The survival of nematode larvae in solutions of many compounds that are poisonous to humans is related to the low permeability of their multi-layered cuticle and also to the anaerobic metabolism of those worms [16,17]. For example, at the first and the second stages of development, nematodes of the Strongyloides genus feed on various types of organic remains in soil, and, therefore, they are less tolerant to the toxic impact [18,19]. At the third larval age, these nematodes eat almost nothing (which is associated with the search for and invasion of the organism of a vertebrate host), and therefore they survive in ten-fold more concentrated solutions of compounds that are poisonous to nematodes.

People often conclude that compounds are toxic if their concentrations cause the death of 50% of laboratory vertebrate animals (Rattus Fischer, 1803, Mus Linnaeus, 1766, etc.). However, dozens of thousands of compounds, which are chemically synthesized and distributed in the conditions of urban agglomerations, are toxic to invertebrates at different doses than those established for vertebrates. Only over recent years has deep research begun into how chemically synthesized organic compounds are impacting invertebrates [20,21].

Studying contaminations that had been provoked by intense and often uncontrolled use of pesticides in agrocenoses has caused the emergence of a new direction in combat against agricultural pests: the development of biopesticides that contain those compounds. Ntalli and Caboni [22] determined the nematocidal properties of thymol in 25–250 mg/kg doses and also its activity when introduced to the soil (0, 50, 100, and 150 mg/kg) combined with benzaldehyde.

Many organic compounds occur in the essential oils of plants. Kang et al. [23] confirmed the nematocidal actions of essential oil constituents against pine nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (Steiner and Buhrer, 1934). They evaluated the inhibiting properties of 97 compounds of essential oils (49 monoterpenes, 17 phenylpropenes, 16 sesquiterpenes, and 15 sulfides) towards the activity of the acetylcholinesterase enzyme of B. xylophilus.

Oka et al. [24] evaluated in vitro nematocidal activity of essential oils from 27 spicy-aromatic plants. According to their studies, essential oils from Carum carvi L., Foeniculum vulgare Mill., Mentha rotundifolia (L.), and M. spicata L. had notable nematocidal properties against root-knot nematode M. javanica (Treub, 1885; Chitwood, 1949). They were also able to inhibit the emergence of those nematodes from eggs. Oka [25] reported nematocidal actions towards M. javanica demonstrated by such constituents of essential oils as trans-cinnamaldehyde, 2-furaldehyde, benzaldehyde, and p-anisaldehyde. In our earlier articles [26,27], we reported the nematocidal properties of those compounds against nematode larvae that are parasites of ruminants.

The objective of this article was to evaluate the survival of the nematodes—wide-spread parasites of ruminants and humans (Strongyloides papillosus (Wedl, 1856) and Haemonchus contortus (Rudolphi, 1803)) in various concentrations of aqueous solutions of organic compounds that are broadly used in households, the food industry, and construction.

2. Materials and Methods

In the experiment, we used Capra aegagrus hircus goat feces (Linnaeus, 1758), infected naturally by S. papillosus and H. contortus in the territory of the Clinical Diagnostic Center of the Dnipro State Agrarian-Economic University (Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, Ukraine, coordinates: 48.421341° N, 35.051363° E). Using the generally accepted parasitological method—copro-helminth ovoscopic McMaster technique [28]—we isolated eggs of nematodes of the Rhabditida [29] order from the animals. Through 10-day cultivation at the temperature of 18–22 °C, and also using the Baermann test, we obtained free-living larvae of various ages—L1, L2, and L3 [28]. According to their morphological specifics, we determined the following species of nematodes: S. papillosus of the Strongylida order and H. contortus of the Rhabditida order [30,31]. In the experiment, we used a mixture of different-age larvae of Strongyloides papillosus, and separate studies were carried out on third-age Haemonchus contortus larvae. When we were identifying the species, we took into account body length, total maximum body width, length of tail end, length of the esophagus, and also specifics of its structure (filiform or rhabditiform with the bulbous), length of the intestine, and specifics of its structure as well (presence or absence of notable intestinal cells, their number, form, arrangement). The experiments were carried out on non-invasive larvae (first–second stages of the development) of S. papillosus and also invasive larvae (third stages of the development) of S. papillosus and H. contortus.

The experimental nematode larvae, obtained using the Baermann method, were centrifuged in water for 4 min at 1500 rpm. Then, the supernatant was removed, and the sediment with larvae was uniformly distributed in 1.5 mL plastic test tubes. In the experiment, in five repetitions, we used 18–22 larvae of S. papillosus in each test tube (about 29,200 overall), 12–14 third-age larvae of S. papillosus (about 19,400 specimens), and 16–17 third-age larvae of H. contortus (about 2500 specimens): for 64 compounds, we tested four concentrations and the control in five repetitions of each variant of the experiment. In the experiment, we used 1%, 0.1%, 0.01%, and 0.001% solutions of the organic compounds. The larvae were exposed to those compounds for 24 h at a temperature of 22 °C. After the experiment, we counted live and dead (immobile specimens with deformed intestinal cells) nematodes.

The larvae were subjected to 62 organic compounds (Table 1) in five repetitions for each of the variants of the experiment and also in the control.

Table 1.

Brief characteristics of the organic compounds used in the laboratory experiment.

The statistical analysis of the results was performed through a set of Statistica 8.0 (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). The tables present mean value (x) ± standard deviation (SD). We used the Tukey test for each of the compounds to calculate the significance of differences in the effects of various concentrations on the nematodes.

3. Results

The greatest negative impacts on the nematode larvae were exerted by glutaraldehyde, thioacetic acid, 3-furoic acid, diethyl malonate, 2-oxopentanedioic acid, butan-1-amine, isovaleric acid, ethyl acetoacetate, phenol and naphthol-2. Twenty-four-hour exposure to 1% solutions of those compounds killed 100% of the S. papillosus larvae of all the development stages and also the H. contortus larvae of the third (invasive) stage (Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 2.

Mortality of larvae of S. papillosus and H. contortus (%) during 24 h laboratory experiment under the influence of acyclic organic compounds (x ± SD, each experiment was repeated five times).

Table 3.

Mortality of larvae of S. papillosus and H. contortus (%) during 24 h laboratory experiment under the influence of cyclic organic compounds (x ± SD, each experiment was repeated five times).

Table 4.

Mortality of larvae of S. papillosus, H. contortus (%) during 24 h laboratory experiment under the influence of sulfur- and nitrogen-containing organic compounds (x ± SD, each experiment was repeated five times).

Over 90% of all the examined species of larvae of various development stages died in the in vitro experiments under the effects of ethyl pyruvate (Table 2). Tert butyl carboxylic acid, 3,7-dimethyl-6-octanoic acid, isobutanaldehyde, phenyl ether, butyl acrylate, maleic anhydride, 1-phenylethan-1-amine appeared to be less toxic to H. contortus of the third (invasive) stage. Over 24 h, in 1% solution, over 60% of the larvae of this species died (Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4).

Of the acyclic organic compounds, the lowest LC50 parameters for the non-invasive larvae and invasive larvae of S. papillosus were produced by 2-oxopentanedioic acid, S. papillosus, and by diethyl malonate and 2-oxopentanedioic acid for the H. contortus larvae (Table 2).

Similar results were produced by the influence of phenol (carbolic acid) on the non-invasive and invasive nematode larvae: LC50 of this compound did not exceed 0.0049 for S. papillosus and 0.0518 for H. contortus (Table 3). However, stronger effects on the nematode larvae of various stages of development were exerted by cyclic organic compound 2-naphthol (Table 3).

Of the sulfur- and nitrogen-containing organic compounds, notable negative impacts were displayed by thioacetic acid and hexylamine (Table 4). Over 90% of the S. papillosus larvae died even in 0.01% thioacetic acid solution. The most thioacetic acid-resistant larvae were observed to be H. contortus. We saw 100% death of the larvae of this nematode species in the exposure to 0.1% concentration of thioacetic acid.

The weakest effects on the nematode larvae of various development stages were exerted by 6-aminocaproic acid, butyl glycol, gallic acid-1-hydrate, hydroquinone, glutamic acid, methyl-2-nitroimidazole-5, dibutyl phthalate, carnitine, octadecanol-1, oleic acid, ornithine monohydrochloride, propylene glycol-1,2, stearyl alcohol, taurine, succinic anhydride, 4-methyl-2-pentanol, maleic acid, 2-pentanone, methanol, phytol, propan-2-ol. All the invasive S. papillosus and H. contortus larvae survived exposure to 1% solutions of those compounds. Additionally, over 70% of the non-invasive development stages of S. papillosus remained vital for 24 h after being subject to the same concentration of the organic compounds (Table 2).

4. Discussion

The obtained results indicate notable nematocidal properties of 28 compounds: 1-phenylethan-1-amine, 2-methylbutanoic acid, 2-oxopentanedioic acid, 3,7-dimethyl-6-octenoic acid, 3-furoic acid, 5-methylfurfural, allyl acetoacetate, anisole, butan-1-amine, butyl acrylate, cyclohexanol, diethyl malonate, ethyl acetoacetate, ethyl pyruvate, glutaraldehyde, isobutyraldehyde, isovaleric acid, maleic anhydrid, methyl acetoacetate, naphthol-2, phenol, phenyl ether, piperonyl alcohol, pyrocatechin, resorcinol, tert butyl carboxylic acid, hexylamine, and thioacetic acid.

Glutaraldehyde is an organic compound, the properties of which are being researched all around the globe [33]. The efficiency of glutaraldehyde was confirmed against fungi, bacteria, and viruses [34,35]. According to the results of our studies, a 1% concentration of this compound was toxic to the larvae of S. papillosus and H. contortus. Further research on its anthelmintic properties is of great interest to veterinary specialists and agronomists for the purposes of designing treatment and prophylaxis measures in livestock enterprises and for combating nematodes that are pests to agricultural plants.

Chitwood [36] described the antagonistic activities of compounds present in plants, including phenols, against nematodes that are pests of agricultural plants. The results of our studies of nematocidal properties of phenol against nematode larvae that are pests of agricultural animals indicate the negative effect of this compound as well. Its 0.1% solution killed the S. papillosus and H. contortus larvae of all stages in 24 h.

The great potential of plant compounds in combating plant nematodes was also described by Andrés et al. [37]. They determined that these compounds may be used as nematocides and be included as components of complex pesticide mixtures with increased efficacy. Ajith et al. [38] studied the nematocidal properties of eugenol—one of the main components of Ocimum and Dianthus essential oils—against Meloidogyne graminicola (Golden and Birchfield, 1965). Our previous studies of the nematocidal potentials of essential oils indicate that the essential oil Syzygium aromaticum (L.) has a toxic effect on nematode larvae of ruminants in in vitro conditions [39].

Stavropoulou et al. [40] also report the toxic activity of eugenol towards bulb nematodes Ditylenchus dipsaci (Kühn, 1857) isolated from infested garlic cloves. Helal et al. [41] report anthelmintic properties of coriander extract (which contains eugenol) on third-stage larvae of ruminant nematodes H. contortus, Trichostrongylus axei (Cobbold, 1879), T. colubriformis (Giles, 1892), T. vitrines (Nisbet and Gasser, 2004), Teladorsagia circumcincta (Stadelman, 1894) and Cooperia oncophora (Railliet, 1898). Silva et al. [42] expressed great concern regarding the tolerance of H. contortus to synthetic anthelmintic drugs. These scientists determined that the greatest effect exerted by plant monoterpenes against this nematode species was exhibited by carvacrol (IC50 = 185.9 µg/mL) and thymol (IC50 = 187.0 µg/mL).

Essential oils have been found to be a new source of human- and environment-safe compounds that have nematocidal activity towards pests of agricultural crops, including nematodes that are plant parasites, as reported by Avato et al. [43], Eloh et al. [44], D’Addabbo and Avato [45], and Douda et al. [46]. Earlier, we reported the nematocidal properties of some organic acids and also other organic compounds [47].

Therefore, many organic compounds present in cells of living organisms (plants, fungi, animals, including nematodes) cause no negative impact (phytol, 3-hydroxy-2-butanone, maleic acid, oleic acid, hydroquinone, gallic acid-1-hydrate, taurine, 6-aminocaproic acid, glutamic acid, carnitine, ornithine monohydrochloride) on the vitality of parasitic nematodes even in 10 g/L concentrations (i.e., in 1% solution, tested in our experiment). Despite being abundant in nature, some of those compounds can be lethal to nematodes (3,7-dimethyl-6-octenoic acid, isovaleric acid, glycolic acid, 2-oxopentanedioic acid, 2-methylbutanoic acid, anisole, 4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzyl alcohol, furfuryl alcohol). Those particular compounds are of the greatest interest for ecologically clean control of nematodes in the conditions of maintenance of animals on-premises and on farms.

Some of the compounds we tested are chemically synthesized xenobiotics. They are introduced into the soil with industrial and municipal wastes. According to the results of our studies, these compounds could pose a serious threat to nematode larvae (glutaraldehyde, 1,4-diethyl 2-methyl-3-oxobutanedioate, hexylamine, diethyl malonate, allyl acetoacetate, tert butyl carboxylic acid, butyl acrylate, 3-methyl-2-butanone, isobutyraldehyde, methyl acetoacetate, ethyl acetoacetate, ethyl pyruvate, 3-methylbutanal, cyclohexanol, cyclooctanone, phenol, pyrocatechin, resorcinol, naphthol-2, phenyl ether, piperonyl alcohol, 3-furoic acid, maleic anhydrid, 5-methylfurfural, thioacetic acid, butan-1-amine, dimethylformamide, 1-phenylethan-1-amine, 3-aminobenzoic acid). Apparently, some of these xenobiotics had no negative impact on the larvae of the parasitic nematodes (methanol, propan-2-ol, isoamyl alcohol, propylene glycol-1,2, octadecanol-1, 4-methyl-2-pentanol, 2-ethoxyethanol, butyl glycol, 2-pentanone, cyclopentanol, ortho-dimethylbenzene, dibutyl phthalate, succinic anhydride, 2-methylfuran, 2-methyl-5-nitroimidazole).

The lowest LC50 of all the compounds we tested were observed for 28 of them: 1-phenylethan-1-amine, 2-methylbutanoic acid, 2-oxopentanedioic acid, 3,7-dimethyl-6-octenoic acid, 3-furoic acid, 5-methylfurfural, allyl acetoacetate, anisole, butan-1-amine, butyl acrylate, cyclohexanol, diethyl malonate, ethyl acetoacetate, ethyl pyruvate, glutaraldehyde, isobutyraldehyde, isovaleric acid, maleic anhydrid, methyl acetoacetate, naphthol-2, phenol, phenyl ether, piperonyl alcohol, pyrocatechin, resorcinol, tert butyl carboxylic acid, hexylamine, thioacetic acid. Since most of them are toxic to vertebrates and invertebrates (Table 5), they could not be applied in the natural conditions of pastures. However, 3,7-dimethyl-6-octenoic acid, 5-methylfurfural, anisole, cyclohexanol, diethyl malonate, ethyl acetoacetate, methyl acetoacetate, and phenyl ether could be used for further experiments in livestock premises, because they exhibit sufficiently low-toxicity to vertebrates and are efficient in killing nematodes (Table 5).

Table 5.

Nematocidal activity for larvae of S. papillosus and H. contortus (our data) and toxicity * to vertebrate animals (rats and mice *, the literature data, https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov accessed on 10 January 2023).

5. Conclusions

Thus, the compounds that in 1% solutions displayed lethal actions towards the free-living stages of the nematode larvae of S. papillosus and H. contortus, are promising for further experiments.

Organic compounds that are used in various spheres of human activity and often occur in nature can exhibit appreciable nematocidal properties. The results we obtained could be used for combating invasive nematode larvae that are parasites of agricultural animals in the environment in order to decrease toxic pesticide loading on natural ecosystems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.B. and V.B.; methodology, O.B.; validation, V.B.; formal analysis, V.B.; investigation, O.B.; resources, O.B. and V.B.; data curation, O.B. and V.B.; writing—original draft preparation, O.B. and V.B.; writing—review and editing, O.B. and V.B.; visualization, O.B. and V.B.; supervision, O.B. and V.B.; project administration, O.B.; funding acquisition, O.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, grant number 0120U102384 “Evaluation of antiparasitic properties of medicinal plants in livestock production” (2023–2025).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Demeler, J.; Küttler, U.; von Samson-Himmelstjerna, G. Adaptation and evaluation of three different in vitro tests for the detection of resistance to anthelmintics in gastrointestinal nematodes of cattle. Vet. Parasitol. 2010, 170, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, F.; Marques, C.B.; Reginato, C.Z.; Brauning, P.; Osmari, V.; Fernandes, F.; Sangioni, L.A.; Vogel, F.S.F. Field and molecular evaluation of anthelmintic resistance of nematode populations from cattle and sheep naturally infected pastured on mixed grazing areas at Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Acta Parasitol. 2020, 65, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyko, O.O.; Brygadyrenko, V.V. Nematocidial activity of aqueous solutions of plants of the families Cupressaceae, Rosaceae, Asteraceae, Fabaceae, Cannabaceae and Apiaceae. Biosyst. Divers. 2019, 27, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowarska, D.; Kiedrzyńska, E. Xenobiotics as a contemporary threat to surface waters. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 2022, 22, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyko, O.O.; Brygadyrenko, V.V. The impact of certain flavourings and preservatives on the survivability of eggs of Ascaris suum and Trichuris suis. Regul. Mech. Biosyst. 2020, 11, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyko, O.; Brygadyrenko, V. Nematicidal activity of organic food additives. Diversity 2022, 14, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyko, O.; Brygadyrenko, V. Nematicidal activity of inorganic food additives. Diversity 2022, 14, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, M.; Frihling, B.E.F.; Velasques, J.; Filho, F.J.C.M.; Cavalheri, P.S.; Migliolo, L. Pharmaceuticals residues and xenobiotics contaminants: Occurrence, analytical techniques and sustainable alternatives for wastewater treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 705, 135568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonelli, F.C.P.; Tonelli, F.M.P. Concerns and threats of xenobiotics on aquatic ecosystems. In Bioremediation and Biotechnology; Bhat, R., Hakeem, K., Saud Al-Saud, N., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyko, A.A.; Brygadyrenko, V.V. Changes in the viability of Strongyloides ransomi larvae (Nematoda, Rhabditida) under the influence of synthetic flavourings. Regul. Mech. Biosyst. 2017, 8, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyko, O.O.; Brygadyrenko, V.V. The impact of certain flavourings and preservatives on the survivability of larvae of nematodes of Ruminantia. Regul. Mech. Biosyst. 2018, 9, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laznik, Ž.; Košir, I.J.; Košmelj, K.; Murovec, J.; Jagodič, A.; Trdan, S.; Ačko, D.K.; Flajšman, M. Effect of Cannabis sativa L. root, leaf and inflorescence ethanol extracts on the chemotrophic response of entomopathogenic nematodes. Plant Soil 2020, 455, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, L.E.M.; de Souza Ferreira, O.B.A.; Machado, A.L.; Costa, J.N.; de Souza Perinotto, W.M. Monitoring environmental conditions on the speed of development and larval migration of gastrointestinal nematodes in Urochloa decumbens in northeastern Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 2022, 31, 100732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, A.; Valek, L.; Schneider, I.; Bollmann, A.; Knopp, G.; Seitz, W.; Schulte-Oehlmann, U.; Oehlmann, J.; Wagner, M. Ecotoxicological impacts of surface water and wastewater from conventional and advanced treatment technologies on brood size, larval length, and cytochrome P450 (35A3) expression in Caenorhabditis elegans. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 13868–13880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oota, M.; Tsai, A.Y.L.; Aoki, D.; Matsushita, Y.; Toyoda, S.; Fukushima, K.; Saeki, K.; Toda, K.; Perfus-Barbeoch, L.; Favery, B.; et al. Identification of naturally occurring polyamines as root-knot nematode attractants. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehy, B.A.; Ho, N.F.H.; Burton, P.S.; Day, J.S.; Geary, T.G.; Thompson, D.P. Transport of model peptides across Ascaris suum cuticle. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2000, 105, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hüttemann, M.; Schmahl, G.; Mehlhorn, H. Light and electron microscopic studies on two nematodes, Angiostrongylus cantonensis and Trichuris muris, differing in their mode of nutrition. Parasitol. Res. 2007, 101, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.A.F.; Whiley, H.; Ross, K.E. A Review of Strongyloides spp. environmental sources worldwide. Pathogens 2019, 8, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyko, O.O.; Kabar, A.M.; Brygadyrenko, V.V. Nematicidal activity of aqueous tinctures of medicinal plants against larvae of the nematodes Strongyloides papillosus and Haemonchus contortus. Biosyst. Divers. 2020, 28, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martynov, V.O.; Brygadyrenko, V.V. The influence of synthetic food additives and surfactants on the body weight of larvae of Tenebrio molitor (Coleoptera, Tenebrionidae). Biosyst. Divers. 2017, 25, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, V.M.; Romanenko, E.R.; Brygadyrenko, V.V. Influence of herbicides, insecticides and fungicides on food consumption and body weight of Rossiulus kessleri (Diplopoda, Julidae). Biosyst. Divers. 2020, 28, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntalli, N.G.; Caboni, P. Botanical nematicides: A review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 9929–9940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.S.; Kim, E.; Lee, S.H.; Park, I.-K. Inhibition of acetylcholinesterases of the pinewood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus, by phytochemicals from plant essential oils. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2013, 105, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, Y.; Nacar, S.; Putievsky, E.; Ravid, U.; Yaniv, Z.; Spiegel, Y. Nematicidal activity of essential oils and their components against the root-knot nematode. Phytopathology 2000, 90, 710–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oka, Y. Nematicidal activity of essential oil components against the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne javanica. Nematology 2001, 3, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyko, O.O.; Brygadyrenko, V.V. The impact of acids approved for use in foods on the vitality of Haemonchus contortus and Strongyloides papillosus (Nematoda) larvae. Helminthologia 2019, 56, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyko, O.O.; Brygadyrenko, V.V. The viability of Haemonchus contortus (Nematoda, Strongylida) and Strongyloides papillosus (Nematoda, Rhabditida) larvae exposed to concentrations of flavourings and source materials approved for use in and on foods. Vestn. Zool. 2019, 53, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajac, A.M.; Conboy, G.A. Veterinary Clinical Parasitology, 8th ed.; Willey-Blackwell: New York, NY, USA, 2011; 354p. [Google Scholar]

- Hodda, M. Phylum Nematoda Cobb 1932. In: Zhang, Z.-Q. (Ed.) Animal biodiversity: An outline of higher-level classification and survey of taxonomic richness. Zootaxa 2011, 3148, 63–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wyk, A.; Cabaret, J.; Michael, L.M. Morphological identification of nematode larvae of small ruminants and cattle simplified. Vet. Parasitol. 2004, 119, 277–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wyk, J.A.; Mayhew, E. Morphological identifcation of parasitic nematode infective larvae of small ruminants and cattle: A practical lab guide. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 2013, 80, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svobodová, A.; Psotová, J.; Walterová, D. Natural phenolics in the prevention of UV-induced skin damage. A review. Biomed. Papers. 2003, 147, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulraj, M.G.; Ignacimuthu, S.; Gandhi, M.R.; Shajahan, A.; Ganesan, P.; Packiam, S.M.; Al-Dhabi, N.A. Comparative studies of tripolyphosphate and glutaraldehyde cross-linked chitosan-botanical pesticide nanoparticles and their agricultural applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 104, 1813–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, M.A.; O’Malley, M.; Maibach, H.I. Pesticide-related dermatoses. In Kanerva’s Occupational Dermatology; Rustemeyer, T., Elsner, P., John, S.M., Maibach, H.I., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatimah, A.O. Antifungal activity and fourier transform infrared spectrometric characterization of aqueous extracts of Acacia senegal and Acacia tortilis on phytopathogenic fungi. J. Pharm. Res. Int. 2019, 31, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitwood, D.J. Phytochemical based strategies for nematode control. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2002, 40, 221–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrés, M.F.; González-Coloma, A.; Sanz, J.; Burillo, J.; Sainz, P. Nematicidal activity of essential oils: A review. Phytochem. Rev. 2012, 11, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajith, M.; Pankaj; Shakil, N.A.; Kaushik, P.; Rana, V.S. Chemical composition and nematicidal activity of essential oils and their major compounds against Meloidogyne graminicola (rice root-knot nematode). J. Essent. Oil Res. 2020, 32, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyko, O.O.; Brygadyrenko, V.V. Nematicidal activity of essential oils of medicinal plants. Folia Oecol. 2021, 48, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavropoulou, E.; Nasiou, E.; Skiada, P.; Giannakou, I.O. Effects of four terpenes on the mortality of Ditylenchus dipsaci (Kühn) Filipjev. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2021, 160, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helal, M.A.; Abdel-Gawad, A.M.; Kandil, O.M.; Khalifa, M.M.E.; Cave, G.W.V.; Morrison, A.A.; Bartley, D.J.; Elsheikha, H.M. Nematocidal effects of a coriander essential oil and five pure principles on the infective larvae of major ovine gastrointestinal nematodes in vitro. Pathogens 2020, 9, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.R.; Lifschitz, A.L.; Macedo, S.R.D.; Campos, N.R.C.L.; Viana-Filho, M.; Alcântara, A.C.S.; Araújo, J.G.; Alencar, L.M.R.; Costa-Junior, L.M. Combination of synthetic anthelmintics and monoterpenes: Assessment of efficacy, and ultrastructural and biophysical properties of Haemonchus contortus using atomic force microscopy. Vet. Parasitol. 2021, 290, 109345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avato, P.; Laquale, S.; Argentieri, M.P.; Lamiri, A.; Radicci, V.; D’Addabbo, T. Nematicidal activity of essential oils from aromatic plants of Morocco. J. Pest Sci. 2016, 90, 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eloh, K.; Kpegba, K.; Sasanelli, N.; Koumaglo, H.K.; Caboni, P. Nematicidal activity of some essential plant oils from tropical West Africa. Int. J. Pest Manag. 2019, 66, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Addabbo, T.; Avato, P. Chemical composition and nematicidal properties of sixteen essential oils—A review. Plants 2021, 10, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douda, O.; Zouhar, M.; Maňasová, M. Effect of plant essential oils on the mortality of Ditylenchus dipsaci (Kühn, 1857) nematode under in vitro conditions. Plant Soil Environ. 2022, 68, 410–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyko, A.A.; Brygadyrenko, V.V. Changes in the viability of the eggs of Ascaris suum under the influence of flavourings and source materials approved for use in and on foods. Biosyst. Divers. 2017, 25, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).