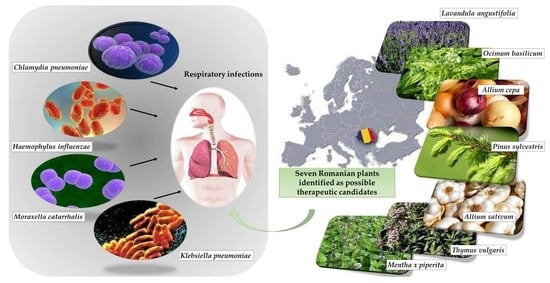

Traditional Medicinal Plants—A Possible Source of Antibacterial Activity on Respiratory Diseases Induced by Chlamydia pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Moraxella catarrhalis

Abstract

1. Introduction

Ethnobotany

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

- Plant-based antibacterial agents active on Chlamydia pneumoniae

- Plant-based antibacterial agents active on Haemophilus influenzae

- Plant-based antibacterial agents active on Klebsiella pneumoniae

- Plant-based antibacterial agents active on Moraxella catarrhalis

- Retrospective discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| C. pneumoniae | Chlamydia pneumoniae |

| H. influenzae | Haemophilus influenzae |

| K. pneumoniae | Klebsiella pneumoniae |

| M. catarrhalis | Moraxella catarrhalis |

| DIZ | diameter of the inhibition zone |

| MIC | minimum inhibitory concentration |

| MBC | minimum bactericidal concentration |

| EO | essential oil |

References

- Christenhusz, M.J.M.; Byng, J.W. The number of known plants species in the world and its annual increase. Phytotaxa 2016, 261, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassagne, F.; Samarakoon, T.; Porras, G.; Lyles, J.T.; Dettweiler, M.; Marquez, L.; Salam, A.M.; Shabih, S.; Farrokhi, D.R.; Quave, C.L. A systematic review of plants with antibacterial activities: A taxonomic and phylogenetic perspective. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 586548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, K.J.; Royal Botanic Garden (RBG) Kew. State of the World’s Plants 2017; Royal Botanic Garden Kew: Richmond, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat Statistics Explained. Respiratory Diseases Statistics. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained (accessed on 14 August 2021).

- Chen, J.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; Jia, Y.; Lin, F.; Xu, J. The prevalence of respiratory pathogens in adults with community-acquired pneumonia in an outpatient cohort. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 2335–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Han, B.; Tong, Q.; Xiao, H.; Cao, D. Detection of eight respiratory bacterial pathogens based on multiplex real-time PCR with fluorescence melting curve analysis. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2020, 2020, 2697230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, S.; Gokhale, S.; Sharma, A.L.; Sapkota, L.B.; Ansari, S.; Gautam, R.; Shrestha, S.; Neopane, P. Burden of bacterial upper respiratory tract pathogens in school children of Nepal. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2017, 4, e000203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelletty, D. Microbiology of bacterial respiratory infections. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 1998, 17, S55–S61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salin, O.P.; Pohjala, L.L.; Saikku, P.; Vuorela, H.J.; Leinonen, M.; Vuorela, P.M. Effects of coadministration of natural polyphenols with doxycycline or calcium modulators on acute Chlamydia pneumoniae infection in vitro. J. Antibiot. 2011, 64, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, S.; Sandeep Rout, S.; Sahoo, G. Ethnobotany: A strategy for conservation of plant. Ann. Rom. Soc. Cell Biol. 2021, 25, 1370–1377. [Google Scholar]

- Butură, V. Romanian Ethnobotany Encyclopedia [Enciclopedia de Etnobotanică Românească]; Editura Stiințifică și Pedagogică: Bucharest, Romania, 1979. (In Romanian) [Google Scholar]

- Petran, M.; Dragos, D.; Gilca, M. Historical ethnobotanical review of medicinal plants used to treat children diseases in Romania (1860s–1970s). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2020, 16, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitalini, S.; Puricelli, C.; Mikerezi, I.; Iriti, M. Plants, people and traditions: Ethnobotanical survey in the Lombard Stelvio National Park and neighbouring areas (central Alps, Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 173, 435–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocârlan, V. Illustrated Flora of Romania: Pteridophyta et Spermatophyta [Flora Ilustrată a României: Pteridophyta et Spermatophyta]; Ceres: Bucharest, Romania, 2009. (In Romanian) [Google Scholar]

- Borza, A. Ethnobotanic Dictionary [Dicționar Etnobotanic]; Editura Academiei Republicii Socialiste România: Bucharest, Romania, 1968. (In Romanian) [Google Scholar]

- Fierăscu, I.; Ortan, A.; Avramescu, S.M.; Dinu-Pîrvu, C.E.; Ionescu, D. Romanian aromatic and medicinal plants: From tradition to science. In Aromatic and Medicinal Plants—Back to Nature; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2017; pp. 149–173. [Google Scholar]

- Istudor, V. Aetherolea, resins, iridoids, bitter substances, vitamins [Aetherolea, rezine, iridoide, principii amare, vitamin]. In Pharmacognosy, Phytochemistry, Phytotherapy [Farmacognozie, Fitochimie și Fitoterapie]; Editura Medicală: Bucharest, Romania, 2001; Volume 2. (In Romanian) [Google Scholar]

- Drăgulescu, C.; Mărculescu, A. Plants in Romanian Folk Medicine [Plantele Medicinale în Medicina Populară Românească]; Transilvania University: Brașov, Romania, 2020. (In Romanian) [Google Scholar]

- Istudor, V. Monosacharides, osides and lipids [Oze, ozide si lipide]. In Pharmacognosy, Phytochemistry, Phythotherapy [Farmacognozie, Fitochimie și Fitoterpie]; Editura Medicală: București, Romania, 1998; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Reichling, J. Plant–microbe interactions and secondary metabolites with antibacterial, antifungal and antiviral properties. In Functions and Biotechnology of Plant Secondary Metabolites; Annual Plant Reviews, 39; Wink, M., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, GB, USA, 2010; pp. 214–347. [Google Scholar]

- van Wyk, B.E.; Wink, M. Medicinal Plants of the World, 2nd ed.; Briza Publications: Pretoria, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fabry, W.; Okemo, P.O.; Ansorg, R. Antibacterial activity of East African medicinal plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1998, 60, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos, J.L.; Recio, M.C. Medicinal plants and antimicrobial activity. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 100, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cos, P.; Vlietinck, A.J.; Vanden Berghe, D.; Maes, L. Anti-infective potential of natural products: How to develop a stronger in vitro “proof-of-concept”. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 106, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuete, V. Potential of Cameroonian plants and derived products against microbial infections: A review. Planta Med. 2010, 76, 1479–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, J. In vitro antimicrobial activity of natural products using minimum inhibitory concentrations: Looking for new chemical entities or predicting clinical response. Med. Aromat. Plants 2012, 1, 1000113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noundou, X.S.; Krause, R.W.M.; van Vuuren, S.F.; Ndinteh, D.T.; Olivier, D.K. Antibacterial effects of Alchornea cordifolia (Schumach. and Thonn.) Müll. Arg extracts and compounds on gastrointestinal, skin, respiratory and urinary tract pathogens. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 179, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ács, K.; Balázs, V.L.; Kocsis, B.; Bencsik, T.; Böszörményi, A.; Horváth, G. Antibacterial activity evaluation of selected essential oils in liquid and vapor phase on respiratory tract pathogens. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 18, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orbán-Gyapai, O.; Liktor-Busa, E.; Kúsz, N.; Stefkó, D.; Urbán, E.; Hohmann, J.; Vasas, A. Antibacterial screening of Rumex species native to the Carpathian Basin and bioactivity-guided isolation of compounds from Rumex aquaticus. Fitoterapia 2017, 118, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumurugan, K.; Shihabudeen, M.S.; Hansi, P.D. Antimicrobial activity and phytochemical analysis of selected Indian folk medicinal plants. Int. J. Pharma Sci. Res. IJPSR 2010, 1, 430–434. [Google Scholar]

- Prabuseenivasan, S.; Jayakumar, M.; Ignacimuthu, S. In vitro antibacterial activity of some plant essential oils. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2006, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salin, O.; Törmäkangas, L.; Leinonen, M.; Saario, E.; Hagström, M.; Ketola, R.A.; Saikku, P.; Vuorela, H.; Vuorela, P.M. Corn mint (Mentha arvensis) extract diminishes acute Chlamydia pneumoniae infection in vitro and in vivo. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 12836–12842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakala, E.; Hanski, L.; Yrjönen, T.; Vuorela, H.; Vuorela, P.M. The lignan-containing extract of Schisandra chinensis berries inhibits the growth of Chlamydia pneumoniae. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2015, 10, 1001–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entrocassi, A.C.; Catalano, A.V.; Ouviña, A.G.; Wilson, E.G.; López, P.G.; Fermepin, M.R. In vitro inhibitory effect of Hydrocotyle bonariensis Lam. extracts over Chlamydia trachomatis and Chlamydia pneumoniae on different stages of the chlamydial life cycle. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapp, K.; Hakala, E.; Orav, A.; Pohjala, L.; Vuorela, P.; Püssa, T.; Vuorela, H.; Raal, A. Commercial peppermint (Mentha × piperita L.) teas: Antichlamydial effect and polyphenolic composition. Food Res. Int. 2013, 53, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salin, O.; Alakurtti, S.; Pohjala, L.; Siiskonen, A.; Maass, V.; Maass, M.; Yli-Kauhaluoma, J.; Vuorela, P. Inhibitory effect of the natural product betulin and its derivatives against the intracellular bacterium Chlamydia pneumoniae. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010, 80, 1141–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauze-Baranowska, M.; Głód, D.; Kula, M.; Majdan, M.; Hałasa, R.; Matkowski, A.; Kozłowska, W.; Kawiak, A. Chemical composition and biological activity of Rubus idaeus shoots—A traditional herbal remedy of Eastern Europe. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 14, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquaviva, R.; Menichini, F.; Ragusa, S.; Genovese, C.; Amodeo, A.; Tundis, R.; Loizzo, M.R.; Iauk, L. Antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of Betula aetnensis Rafin. (Betulaceae) leaves extract. Nat. Prod. Res. 2013, 27, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.; Hneini, F.; Na’was, T. Tilia cordata: A potent inhibitor of growth and biofilm formation of bacterial clinical isolates. World J. Pharm. Res. 2019, 8, 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Chegini, H.; Oshaghi, M.; Boshagh, M.A.; Foroutan, P.; Jahangiri, A.H. Antibacterial effect of Medicago sativa extract on the common bacterial in sinusitis infection. Int. J. Biomed. Public Health 2018, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Salari, M.H.; Amine, G.; Shirazi, M.H.; Hafezi, R.; Mohammadypour, M. Antibacterial effects of Eucalyptus globulus leaf extract on pathogenic bacteria isolated from specimens of patients with respiratory tract disorders. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2006, 12, 194–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hadhrami, R.M.S.; Hossain, M.A. Evaluation of antioxidant, antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities of seed crude extracts of Ammi majus grown in Oman. Egypt. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2016, 3, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Germanò, M.P.; D’Angelo, V.; Sanogo, R.; Catania, S.; Alma, R.; De Pasquale, R.; Bisignano, G. Hepatoprotective and antibacterial effects of extracts from Trichilia emetica Vahl. (Meliaceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 96, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaissi, A.; Rouis, Z.; Ben Salem, N.A.; Mabrouk, S.; Ben Salem, Y.; Salah, K.B.H.; Aouni, M.; Farhat, F.; Chemli, R.; Harzallah-Skhiri, F.; et al. Chemical composition of 8 eucalyptus species’ essential oils and the evaluation of their antibacterial, antifungal and antiviral activities. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 12, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Salinas, G.M.; Pérez-López, L.A.; Becerril-Montes, P.; Salazar-Aranda, R.; Said-Fernández, S.; de Torres, N.W. Evaluation of the flora of Northern Mexico for in vitro antimicrobial and antituberculosis activity. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 109, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Vohra, S.; Arnason, J.T.; Hudson, J.B. Echinacea. Extracts contain significant and selective activities against human pathogenic bacteria. Pharm. Biol. 2008, 46, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanković, N.; Mihajilov-Krstev, T.; Zlatković, B.; Stankov-Jovanović, V.; Mitić, V.; Jović, J.; Čomić, L.; Kocić, B.; Bernstein, N. Antibacterial and antioxidant activity of traditional medicinal plants from the Balkan Peninsula. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2016, 78, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzo, A.; Di Carlo, G.; Biscardi, D.; De Fusco, R.; Mascolo, N.; Borrelli, F.; Capasso, F.; Fasulo, M.P.; Autore, G. Biological screening of Italian medicinal plants for antibacterial activity. Phytother. Res. 1995, 9, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borugă, O.; Jianu, C.; Mişcă, C.; Goleţ, I.; Gruia, A.; Horhat, F. Thymus vulgaris essential oil: Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity. J. Med. Life 2014, 7, 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Fournomiti, M.; Kimbaris, A.; Mantzourani, I.; Plessas, S.; Theodoridou, I.; Papaemmanouil, V.; Kapsiotis, I.; Panopoulou, M.; Stavropoulou, E.; Bezirtzoglou, E.E.; et al. Antimicrobial activity of essential oils of cultivated oregano (Origanum vulgare), sage (Salvia officinalis), and thyme (Thymus vulgaris) against clinical isolates of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella oxytoca, and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2015, 26, 23289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickky, B.; Abbas, M.; El-Shhaby, O. Economic maximization of alfalfa antimicrobial efficacy using stressful factors. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 8, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mwambete, K.D. The in vitro antimicrobial activity of fruit and leaf crude extracts of Momordica charantia: A Tanzania medicinal plant. Afr. Health Sci. 2009, 9, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Akharaiyi, F.C.; Boboye, B. Antibacterial, phytochemical and antioxidant properties of Cnestis ferruginea DC (Connaraceae) extracts. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 2012, 2, 592–609. [Google Scholar]

- Khumalo, G.; Sadgrove, N.; van Vuuren, S.; Van Wyk, B.-E. Antimicrobial activity of volatile and non-volatile isolated compounds and extracts from the bark and leaves of Warburgia salutaris (Canellaceae) against skin and respiratory pathogens. South Afr. J. Bot. 2019, 122, 547–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, T.R.H.; Kuete, V.; Jäger, A.K.; Meyer, J.J.M.; Lall, N. Antimicrobial activity of selected South African medicinal plants. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 12, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomogne-Fodjo, M.; Van Vuuren, S.; Ndinteh, D.; Krause, R.; Olivier, D. Antibacterial activities of plants from Central Africa used traditionally by the Bakola pygmies for treating respiratory and tuberculosis-related symptoms. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 155, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noundou, X.S.; Krause, R.; van Vuuren, S.; Ndinteh, D.T.; Olivier, D. Antibacterial activity of the roots, stems and leaves of Alchornea floribunda. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 151, 1023–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, B.; Sah, G.; Basnet, B.; Bhatt, M.; Sharma, D.; Subedi, K.; Janardhan, P.; Malla, R. Phytochemical extraction and antimicrobial properties of different medicinal plants: Ocimum sanctum (Tulsi), Eugenia caryophyllata (clove), Achytanthes bidentata (Datiwan) and Azadirachta indica (Neem). J. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2011, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, M.; Masoumipour, F.; Hassanshahian, M.; Jafarinasab, T. Study the antibacterial and antibiofilm activity of Carum copticum against antibiotic-resistant bacteria in planktonic and biofilm forms. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 129, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bayati, F.A.; Al-Mola, H.F. Antibacterial and antifungal activities of different parts of Tribulus terrestris L. growing in Iraq. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2008, 9, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifeanyichukwu, U.L.; Fayemi, O.E.; Ateba, C.N. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from pomegranate (Punica granatum) extracts and characterization of their antibacterial activity. Molecules 2020, 25, 4521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaei-Ghomi, J.; Ahd, A.A. Antimicrobial and antifungal properties of the essential oil and methanol extracts of Eucalyptus largiflorens and Eucalyptus intertexta. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2010, 6, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mariri, A.; Safi, M. In vitro antibacterial activity of several plant extracts and oils against some gram-negative bacteria. Iran. J. Med. Sci. 2014, 39, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Al Abbasy, D.W.; Pathare, N.; Al-Sabahi, J.N.; Alam Khan, S. Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of essential oil isolated from Omani basil (Ocimum basilicum Linn.). Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis. 2015, 5, 645–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Jalel, L.F.; Elkady, W.M.; Gonaid, M.H.; El-Gareeb, K.A. Difference in chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of Thymus capitatus L. essential oil at different altitudes. Futur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 4, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadollahi, M.; Firuzi, O.; Jamebozorgi, F.H.; Alizadeh, M.; Jassbi, A.R. Ethnopharmacological studies, chemical composition, antibacterial and cytotoxic activities of essential oils of eleven Salvia in Iran. J. Herb. Med. 2019, 17–18, 100250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suliman, S.; Van Vuuren, S.; Viljoen, A. Validating the in vitro antimicrobial activity of Artemisia afra in polyherbal combinations to treat respiratory infections. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2010, 76, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vuuren, S.; Docrat, Y.; Kamatou, G.; Viljoen, A. Essential oil composition and antimicrobial interactions of understudied tea tree species. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2014, 92, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozliman, S.; Yaldiz, G.; Camlica, M.; Ozsoy, N. Chemical components of essential oils and biological activities of the aqueous extract of Anethum graveolens L. grown under inorganic and organic conditions. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2021, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen-Utsukarci, B.; Dosler, S.; Taskin, T.; Abudayyak, M.; Ozhan, G.; Mat, A. An evaluation of antioxidant, antimicrobial, antibiofilm and cytotoxic activities of five Verbascum species in Turkey. Farmacia 2018, 66, 1014–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girish, H.; Satish, S. Antibacterial activity of important medicinal plants on human pathogenic bacteria-a comparative analysis. World Appl. Sci. J. 2007, 5, 267–271. [Google Scholar]

- Lalitha, S.; Rajeshwaran, K.; Kumar, P.; Deepa, K.; Gowthami, K. In vivo screening of antibacterial activity of Acacia mellifera (BENTH) (Leguminosae) on human pathogenic bacteria. Glob. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 4, 148–150. [Google Scholar]

- Arya, P.; Mehta, J.P.; Kumar, S. Antibacterial action of medicinal plant Alysicarpus vaginalis against respiratory tract pathogens. Int. J. Environ. Rehabil. Conserv. 2016, 7, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Vaghasiya, Y.; Chanda, S. Screening of some traditionally used Indian plants for antibacterial activity against Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Herb. Med. Toxicol. 2009, 3, 161–164. [Google Scholar]

- Pimpliskar, M.R.; Jadhav, R.; Ughade, Y. Preliminary phytochemical and pharmacological screening of Pogostemon benghalensis for antioxidant and antibacterial activity. Asian J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2021, 7, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.A.N.; Ashrafuzzaman, M.; Ali, M.H.; Liza, L.N.; Zinnah, K.M.A. Antimicrobial activity of some medicinal plants against multi drug resistant human pathogens. Adv. Biosci. Bioeng. 2013, 1, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hossan, S.; Jindal, H.; Maisha, S.; Raju, C.S.; Sekaran, S.D.; Nissapatorn, V.; Kaharudin, F.; Yi, L.S.; Khoo, T.J.; Rahmatullah, M.; et al. Antibacterial effects of 18 medicinal plants used by the Khyang tribe in Bangladesh. Pharm. Biol. 2018, 56, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, C.W.; Chan, Y.S.; Chan, S.M.; Chan, M.W.; Teh, E.L.; Soh, C.L.D.; Khoo, K.S.; Ong, H.C.; Sit, N.W. Antifungal, antibacterial and cytotoxic activities of non-indigenous medicinal plants naturalised in Malaysia. Farmacia 2020, 68, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundararajan, B.; Moola, A.K.; Vivek, K.; Kumari, B. Formulation of nanoemulsion from leaves essential oil of Ocimum basilicum L. and its antibacterial, antioxidant and larvicidal activities (Culex quinquefasciatus). Microb. Pathog. 2018, 125, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, R. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Ocimum basilicum L. (sweet basil) from Western Ghats of Northwest Karnataka, India. Anc. Sci. Life 2014, 33, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaio, I.; Saggiorato, A.G.; Treichel, H.; Cichoski, A.J.; Astolfi, V.; Cardoso, R.I.; Toniazzo, G.; Valduga, E.; Paroul, N.; Cansian, R.L. Antibacterial activity of basil essential oil (Ocimum basilicum L.) in Italian-type sausage. J. Verbrauch. Lebensm. 2015, 10, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.; Ferreira, S.; Queiroz, J.; Domingues, F. Coriander (Coriandrum sativum L.) essential oil: Its antibacterial activity and mode of action evaluated by flow cytometry. J. Med. Microbiol. 2011, 60, 1479–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamoud, R.; Sporer, F.; Reichling, J.; Wink, M. Antimicrobial activity of a traditionally used complex essential oil distillate (Olbas® Tropfen) in comparison to its individual essential oil ingredients. Phytomedicine 2012, 19, 969–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meriga, B.; Mopuri, R.; Muralikrishna, T. Insecticidal, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of bulb extracts of Allium sativum. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2012, 5, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunes, H.; Gulen, D.; Mutlu, R.; Gumus, A.; Tas, T.; Topkaya, A.E. Antibacterial effects of curcumin: An in vitro minimum inhibitory concentration study. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2016, 32, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollár, M.; Gyovai, A.; Szűcs, P.; Zupkó, I.; Marschall, M.; Csupor-Loffler, B.; Bérdi, P.; Vecsernyés, A.; Csorba, A.; Liktor-Busa, E.; et al. Antiproliferative and antimicrobial activities of selected bryophytes. Molecules 2018, 23, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iauk, L.; Acquaviva, R.; Mastrojeni, S.; Amodeo, A.; Pugliese, M.; Ragusa, M.; Loizzo, M.R.; Menichini, F.; Tundis, R. Antibacterial, antioxidant and hypoglycaemic effects of Thymus capitatus (L.) Hoffmanns. et Link leaves’ fractions. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2015, 30, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglisi, S.; Speciale, A.; Acquaviva, R.; Ferlito, G.; Ragusa, S.; De Pasquale, R.; Iauk, L. Antibacterial activity of Helleborus bocconei Ten. subsp. siculus root extracts. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 125, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauze-Baranowska, M.; Majdan, M.; Hałasa, R.; Głód, D.; Kula, M.; Fecka, I.; Orzeł, A. The antimicrobial activity of fruits from some cultivar varieties of Rubus idaeus and Rubus occidentalis. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 2536–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, T.; van Vuuren, S.; De Wet, H. An antimicrobial evaluation of plants used for the treatment of respiratory infections in rural Maputaland, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 144, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, M.U.; Thajuddin, N. Effect of medicinal plants on Moraxella cattarhalis. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2011, 4, 133–136. [Google Scholar]

- Fadipe, V.O.; Opoku, A.R.; Mongalo, N.I. In vitro evaluation of the comprehensive antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of Curtisia dentata (Burm. F) CA Sm: Toxicological effect on the human embryonic kidney (HEK293) and human hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) cell lines. EXCLI J. 2015, 14, 971–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L.; Losier, A.; Tolbert, T.; Dela Cruz, C.S.; Marion, C.R. Atypical pneumonia: Updates on Legionella, Chlamydophila, and Mycoplasma pneumonia. Clin. Chest Med. 2017, 38, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porritt, R.A.; Crother, T.R. Infection and inflammatory diseases. Immunopathol. Dis. Therap. 2016, 7, 237–254. [Google Scholar]

- Shimada, K.; Crother, T.; Karlin, J.; Chen, S.; Chiba, N.; Ramanujan, V.K.; Vergnes, L.; Ojcius, D.; Arditi, M. Caspase-1 dependent IL-1β secretion is critical for host defense in a mouse model of Chlamydia pneumoniae lung infection. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Liu, M.; Ye, Z.; Tan, T.; Liu, X.; You, X.; Zeng, Y.; Wu, Y. Insights into the pathogenesis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae (Review) Corrigendum in/10.3892/mmr.2017.8324. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 17, 4155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyee, A.G.; Yang, X. Role of toll-like receptors in immune responses to chlamydial infections. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2008, 14, 593–600. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, C.C.; Jackson, L.A.; Campbell, L.A.; Grayston, J.T. Chlamydia pneumoniae (TWAR). Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1995, 8, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutlin, A.; Roblin, P.M.; Hammerschlag, M.R. Effect of prolonged treatment with azithromycin, clarithromycin, or levofloxacin on Chlamydia pneumoniae in a continuous-infection model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftekhari, A.; Khusro, A.; Ahmadian, E.; Dizaj, S.M.; Hasanzadeh, A.; Cucchiarini, M. Phytochemical and nutra-pharmaceutical attributes of Mentha spp.: A comprehensive review. Arab. J. Chem. 2021, 14, 103106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, Y. Green Tea; Marcel Dekker Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki, T.; Inoue, M.; Sasaki, N.; Hagiwara, T.; Kishimoto, T.; Shiga, S.; Ogawa, M.; Hara, Y.; Matsumoto, T. In vitro inhibitory effects of tea polyphenols on the proliferation of Chlamydia trachomatis and Chlamydia pneumoniae. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2003, 56, 143–145. [Google Scholar]

- Budiu, L.; Luca, E.; Ona, A.; Muntean, L.; Becze, A.; Simedru, D.; Kovacs, M.; Kovacs, D. Response of antioxidant potential and essential oil components to irrigation and fertilization on three mint species (Mentha spp. L.). Rom. Agric. Res. 2019, 36, 165–171. [Google Scholar]

- Mogosan, C.; Vostinaru, O.; Oprean, R.; Heghes, C.; Filip, L.; Balica, G.; Moldovan, R.I. A comparative analysis of the chemical composition, anti-inflammatory, and antinociceptive effects of the essential oils from three species of Mentha cultivated in Romania. Molecules 2017, 22, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcaru, T.; Diguță, C.; Matei, F. Antimicrobial potential of Romanian spontaneous flora—A minireview. Horticulture 2018, 62, 667–680. [Google Scholar]

- Rastogi, S.; Pandey, M.M.; Rawat, A.K.S. Medicinal plants of the genus Betula—Traditional uses and a phytochemical–pharmacological review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 159, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladimirov, M.S.; Nikolić, V.D.; Stanojević, L.P.; Nikolić, L.B.; Dinić, A. Common birch (Betula pendula Roth.): Chemical composition and biological activity of isolates. Adv. Technol. 2019, 8, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehelean, C.A.; Şoica, C.; Ledeţi, I.; Aluaş, M.; Zupko, I.; Gǎluşcan, A.; Cinta-Pinzaru, S.; Munteanu, M. Study of the betulin enriched birch bark extracts effects on human carcinoma cells and ear inflammation. Chem. Central J. 2012, 6, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Snafi, A.; Hanaa, S.; Khadem; Al-Saedy, H.; Alqahtani, A.; Batiha, G.; Jafari Sales, A. A review on Medicago sativa: A potential medicinal plant. Int. J. Biol. Pharm. Sci. Arch. 2021, 1, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabudak, T.; Guler, N. Trifolium L.—A review on its phytochemical and pharmacological profile. Phytother. Res. 2009, 23, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A. Biological activities of Trifolium pratense: A review. Acta Sci. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 3, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hanski, L.; Genina, N.; Uvell, H.; Malinovskaja, K.; Gylfe, Å.; Laaksonen, T.; Kolakovic, R.; Mäkilä, E.; Salonen, J.; Hirvonen, J.; et al. Inhibitory activity of the isoflavone biochanin A on intracellular bacteria of genus Chlamydia and initial development of a buccal formulation. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e115115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazăre, R.; Neaga, B.; Timariu, R.; Bostan, C.; Cojocariu, L. Behavior of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) for hay under conditions in Romania. Res. J. Agric. Sci. 2019, 51, 273–281. [Google Scholar]

- Antonescu, I.; Jurca, T.; Gligor, F.; Craciun, I.; Fritea, L.; Patay, E.; Mureșan, M.; Udeanu, D.; Ioniță, C.; Antonescu, A.; et al. Comparative phytochemical and antioxidative characterization of Trifolium pratense L. and Ocimum basilicum L. Farmacia 2019, 67, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanganu, D.; Vlase, L.; Olah, N.-K. LC/MS analysis of isoflavones from Fabaceae species extracts. Farmacia 2010, 58, 177–183. [Google Scholar]

- Slack, M.P.E. A review of the role of Haemophilus influenzae in community-acquired pneumonia. Pneumonia (Nathan) 2015, 6, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, P. Haemophilus influenzae and the lung (Haemophilus and the lung). Clin. Transl. Med. 2012, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, A.J. Respiratory tract infections caused by Haemophilus influenzae in adults. Infection 1987, 15, S109–S112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmu, A.A.I.; Herva, E.; Savolainen, H.; Karma, P.; Mäkelä, P.H.; Kilpi, T.M. Association of clinical signs and symptoms with bacterial findings in acute otitis media. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004, 38, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, K.; Kobayashi, R.; Takada, E.; Ono, A.; Chiba, N.; Morozumi, M.; Iwata, S.; Sunakawa, K.; Ubukata, K.; Meningitis, N.S.B. High prevalence of type b beta-lactamase-non-producing ampicillin-resistant Haemophilus influenzae in meningitis: The situation in Japan where Hib vaccine has not been introduced. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006, 57, 1077–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- García-Cobos, S.; Campos, J.; Lázaro, E.; Román, F.; Cercenado, E.; García-Rey, C.; Pérez-Vázquez, M.; Oteo, J.; de Abajo, F. Ampicillin-resistant non-beta-lactamase-producing Haemophilus influenzae in Spain: Recent emergence of clonal isolates with increased resistance to cefotaxime and cefixime. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 2564–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacconelli, E.; Carrara, E.; Savoldi, A.; Harbarth, S.; Mendelson, M.; Monnet, D.L.; Pulcini, C.; Kahlmeter, G.; Kluytmans, J.; Carmeli, Y.; et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: The WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manea, M.; Cântar, I. Actual state of knowledge regarding research on lime tree in the world—Short review. J. Hortic. For. Biotechnol. 2017, 21, 108–114. [Google Scholar]

- Mircea, C.; Cioancă, O.; Iancu, C.; Stănescu, U.; Hăncianu, M. Microbiological and chemical evaluation of several commercial samples of Tiliae flos. J. Plant Develop. 2016, 23, 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Costea, T.; Vlase, L.; Istudor, V.; Popescu, M.L.; Gîrd, C.E. Researches upon indigenous herbal products for therapeutic valorification in metabolic diseases. Note II. Polyphenols content, antioxidant activity and cytoprotective effect of Betulae folium dry extract. Farmacia 2014, 62, 961–970. [Google Scholar]

- Germanò, M.; Cacciola, F.; Donato, P.; Dugo, P.; Certo, G.; D’Angelo, V.; Mondello, L.; Rapisarda, A. Betula pendula leaves: Polyphenolic characterization and potential innovative use in skin whitening products. Fitoterapia 2012, 83, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maior, M.; Dobrotă, C. Natural compounds discovered in Helleborus sp. (Ranunculaceae) with important medical potential. Cent. Eur. J. Biol. 2013, 8, 272–285. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan, I.; Nechifor, A.; Basea, I.; Hruban, E. Aus der rumänischen Volksmedizin: Unspezifische Reiztherapie durch transkutane Implantation der Nieswurz (Helleborus purpurascens, Fam. Ranunculaceae) bei landwirtschaftlichen Nutztieren” [From Rumanian folk medicine: Non-specific stimulus therapy using transcutaneous implantation of hellebore (Helleborus purpurascens, Fam. Ranunculaceae) in agriculturally useful animals]. DTW Dtsch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 1990, 97, 525–529. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Cioaca, C.; Cucu, V. Quantitative determination of hellebrin in the rhizomes and roots of Helleborus purpurascens W. et K. Planta Med. 1974, 26, 250–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apetrei, N.; Lupu, A.; Calugaru, A.; Kerek, F.; Szegli, G.; Cremer, L. The antioxidant effects of some progressively purified fractions from Helleborus purpurascens. Roum. Biotechnol. Lett. 2011, 16, 6673–6682. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, B. Medicinal properties of Echinacea: A critical review. Phytomedicine 2003, 10, 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimalanathan, S.; Schoop, R.; Suter, A.; Hudson, J. Prevention of influenza virus induced bacterial superinfection by standardized Echinacea purpurea, via regulation of surface receptor expression in human bronchial epithelial cells. Virus Res. 2017, 233, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elek, F.; Eszter, D.; Rebeka, K.; Szende, V.; Melinda, U.; Eszter, L.-Z. Mapping of Echinacea-based food supplements on the Romania market and qualitative evaluation of the most commonly used products. Bull. Med. Sci. 2020, 93, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banica, F.; Bungau, S.; Tit, D.M.; Behl, T.; Otrisal, P.; Nechifor, A.C.; Gitea, D.; Pavel, F.-M.; Nemeth, S. Determination of the total polyphenols content and antioxidant activity of Echinacea purpurea extracts using newly manufactured glassy carbon electrodes modified with carbon nanotubes. Processes 2020, 8, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, S. Essential oils: Their antibacterial properties and potential applications in foods—A review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 94, 223–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharopov, F.; Braun, M.S.; Gulmurodov, I.; Khalifaev, D.; Isupov, S.; Wink, M. Antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities of essential oils of selected aromatic plants from Tajikistan. Foods 2015, 4, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wink, M. Modes of action of herbal medicines and plant secondary metabolites. Medicines 2015, 2, 251–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprotosoaie, A.C.; Miron, A.; Ciocârlan, N.; Brebu, M.; Roşu, C.M.; Trifan, A.; Vochiţa, G.; Gherghel, D.; Luca, S.V.; Niţă, A.; et al. Essential oils of Moldavian Thymus species: Chemical composition, antioxidant, anti-Aspergillus and antigenotoxic activities. Flavour Fragr. J. 2019, 34, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boz, I.; Lobiuc, A.; Tanase, C. Chemical composition of essential oils and secretory hairs of Thymus dacicus Borbás related to harvesting time. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2017, 51, 813–819. [Google Scholar]

- Apetrei, C.; Spac, A.; Brebu, M.; Miron, A.C.; Popa, G. Composition, and antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of the essential oils of a full-grown Pinus cembra L. tree from the Calimani Mountains (Romania). J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2013, 78, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.M.; Bachman, M.A. Colonization, infection, and the accessory genome of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, T.T.; Liebenthal, D.; Tran, T.K.; Vu, B.N.T.; Nguyen, D.N.T.; Tran, H.K.T.; Nguyen, C.K.T.; Vu, H.L.T.; Fox, A.; Horby, P.; et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae oropharyngeal carriage in rural and urban Vietnam and the effect of alcohol consumption. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e91999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farida, H.; Severin, J.A.; Gasem, M.H.; Keuter, M.; Broek, P.V.D.; Hermans, P.W.M.; Wahyono, H.; Verbrugh, H.A. Nasopharyngeal carriage of Klebsiella pneumoniae and other gram-negative bacilli in pneumonia-prone age groups in Semarang, Indonesia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 1614–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podschun, R.; Ullmann, U. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: Epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1998, 11, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jondle, C.N.; Gupta, K.; Mishra, B.B.; Sharma, J. Klebsiella pneumoniae infection of murine neutrophils impairs their efferocytic clearance by modulating cell death machinery. PLOS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsereteli, M.; Sidamonidze, K.; Tsereteli, D.; Malania, L.; Vashakidze, E. Epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in intensive care units of multiprofile hospitals in Tbilisi, Georgia. Georgian Med. News 2018, 280–281, 164–168. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, A.; Husain, A.; Mujeeb, M.; Khan, S.A.; Najmi, A.K.; Siddique, N.A.; Damanhouri, Z.A.; Anwar, F. A review on therapeutic potential of Nigella sativa: A miracle herb. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2013, 3, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooti, W.; Hasanzadeh-Noohi, Z.; Sharafi-Ahvazi, N.; Asadi-Samani, M.; Ashtary-Larky, D. Phytochemistry, pharmacology, and therapeutic uses of black seed (Nigella sativa). Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2016, 14, 732–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topcagic, A.; Zeljkovic, S.C.; Karalija, E.; Galijasevic, S.; Sofic, E. Evaluation of phenolic profile, enzyme inhibitory and antimicrobial activities of Nigella sativa L. seed extracts. Bosn. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2017, 17, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, C.-C.; Olah, N.-K.; Vlase, L.; Mogosan, C.; Mocan, A. Comparative studies on polyphenolic composition, antioxidant and diuretic effects of Nigella sativa L. (black cumin) and Nigella damascena L. (Lady-in-a-Mist) seeds. Molecules 2015, 20, 9560–9574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocabado, G.O.; Bedoya, L.M.; Abad, M.J.; Bermejo, P. Rubus—A review of its phytochemical and pharmacological profile. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2008, 3, 1934578X0800300319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummer, K.E. Rubus pharmacology: Antiquity to the present. HortScience 2010, 45, 1587–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costea, T.; Lupu, A.R.; Vlase, L.; Nencu, I.; Gîrd, C.E. Phenolic content and antioxidant activity of a raspberry leaf dry extract. Rom. Biotechnol. Lett. 2016, 21, 11345–11356. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, N.; Petropoulos, S.; Ferreira, I.C. Chemical composition and bioactive compounds of garlic (Allium sativum L.) as affected by pre- and post-harvest conditions: A review. Food Chem. 2016, 211, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batiha, G.E.-S.; Beshbishy, A.M.; Wasef, L.G.; Elewa, Y.H.A.; Al-Sagan, A.A.; El-Hack, M.E.A.; Taha, A.E.; Abd-Elhakim, Y.M.; Devkota, H.P. Chemical constituents and pharmacological activities of garlic (Allium sativum L.): A review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pârvu, M.; Moţ, C.A.; Pârvu, A.E.; Mircea, C.; Stoeber, L.; Roşca-Casian, O.; Ţigu, A.B. Allium sativum extract chemical composition, antioxidant activity and antifungal effect against Meyerozyma guilliermondii and Rhodotorula mucilaginosa causing onychomycosis. Molecules 2019, 24, 3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifunschi, S.; Munteanu, M.F.; Agotici, V.; Pintea, S.; Gligor, R. Determination of flavonoid and polyphenol compounds in Viscum album and Allium sativum extracts. Int. Curr. Pharm. J. 2015, 4, 382–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teshika, J.D.; Zakariyyah, A.M.; Zaynab, T.; Zengin, G.; Rengasamy, K.R.; Pandian, S.K.; Fawzi, M.M. Traditional and modern uses of onion bulb (Allium cepa L.): A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, S39–S70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakht, J.; Khan, S.; Shafi, M. Antimicrobial potentials of fresh Allium cepa against gram positive and gram-negative bacteria and fungi. Pak. J. Bot. 2013, 45, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tataringa, G.; Spac, A.; Sathyamurthy, B.; Zbancioc, A.M. In silico studies on some Dengue viral proteins with selected Allium cepa oil constituents from Romanian source. Farmacia 2020, 68, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oancea, S.; Draghici, O. pH and thermal stability of anthocyanin-based optimised extracts of Romanian red onion cultivars. Czech J. Food Sci. 2013, 31, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, A.; Naughton, D.P.; Petroczi, A. A systematic review on the herbal extract Tribulus terrestris and the roots of its putative aphrodisiac and performance enhancing effect. J. Diet. Suppl. 2014, 11, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ștefănescu, R.; Farczadi, L.; Huțanu, A.; Ősz, B.E.; Mărușteri, M.; Negroiu, A.; Vari, C.E. Tribulus terrestris efficacy and safety concerns in diabetes and erectile dysfunction, assessed in an experimental model. Plants 2021, 10, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ștefănescu, R.; Tero-Vescan, A.; Negroiu, A.; Aurică, E.; Vari, C.-E. A comprehensive review of the phytochemical, pharmacological, and toxicological properties of Tribulus terrestris L. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinchev, D.; Janda, B.; Evstatieva, L.; Oleszek, W.; Aslani, M.R.; Kostova, I. Distribution of steroidal saponins in Tribulus terrestris from different geographical regions. Phytochemistry 2008, 69, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naquvi, K.J.; Ahamad, J.; Salma, A.; Ansari, S.H.; Najmi, A.K. A critical review on traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacological uses of Origanum vulgare Linn. Int. Res. J. Pharm. 2019, 10, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodhi, S.; Vadnere, G.P.; Sharma, V.K.; Usman, M.R. Marrubium vulgare L.: A review on phytochemical and pharmacological aspects. J. Intercult. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 6, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, B.; Kaack, K. A review of traditional herbal medicinal products with disease claims for elder (Sambucus nigra) flower. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Society for Horticultural Science (ISHS) Symposium, Leuven, Belgium, 12 January 2015; pp. 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarić, S.; Mitrović, M.; Pavlović, P. Review of ethnobotanical, phytochemical, and pharmacological study of Thymus serpyllum L. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2015, 2015, 101978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khair-Ul-Bariyah, S.; Ahmed, D.; Ikram, M. Ocimum basilicum: A review on phytochemical and pharmacological studies. Pak. J. Chem. 2012, 2, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, P.; Ramalingam, P.; Nagarasan, S.; Ranganathan, B.; Gimbun, J.; Shanmugam, K. A comprehensive review on Ocimum basilicum. J. Nat. Remedies 2018, 18, 71–85. [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, S.; Mandal, M. Coriander (Coriandrum sativum L.) essential oil: Chemistry and biological activity. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2015, 5, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laribi, B.; Kouki, K.; M’Hamdi, M.; Bettaieb, T. Coriander (Coriandrum sativum L.) and its bioactive constituents. Fitoterapia 2015, 103, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifan, A.; Bostănaru, A.; Luca, S.; Grădinaru, A.; Jităreanu, A.; Aprotosoaie, A.; Miron, A.; Cioancă, O.; Hăncianu, M.; Ochiuz, L.; et al. Antifungal potential of Pimpinella anisum, Carum carvi and Coriandrum sativum extracts: A comparative study with focus on the phenolic composition. Farmacia 2020, 68, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batiha, G.E.-S.; Olatunde, A.; El-Mleeh, A.; Hetta, H.F.; Al-Rejaie, S.; Alghamdi, S.; Zahoor, M.; Magdy Beshbishy, A.; Murata, T.; Zaragoza-Bastida, A.; et al. Bioactive compounds, pharmacological actions, and pharmacokinetics of wormwood (Artemisia absinthium). Antibiotics 2020, 9, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craciunescu, O.; Constantin, D.; Gaspar, A.; Toma, L.; Utoiu, E.; Moldovan, L. Evaluation of antioxidant and cytoprotective activities of Arnica montana L. and Artemisia absinthium L. ethanolic extracts. Chem. Central J. 2012, 6, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanescu, B.; Vlase, L.; Corciova, A.; Lazar, M.I. HPLC-DAD-MS study of polyphenols from Artemisia absinthium, A. annua, and A. vulgaris. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2010, 46, 468–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanescu, B.; Tuchiluș, C.; Corciovă, A.; Apetrei, C.; Mihai, C.T.; Gheldiu, A.-M.; Vlase, L. Antioxidant, antimicrobial and cytotoxic activity of Tanacetum vulgare, Tanacetum corymbosum and Tanacetum macrophyllum extracts. Farmacia 2018, 66, 282–288. [Google Scholar]

- Benedec, D.; Oniga, I.; Oprean, R.; Tamas, M. Chemical composition of the essential oils of Ocimum basilicum L. cultivated in Romania. Farmacia 2008, 57, 625–629. [Google Scholar]

- Andro, A.; Zamfirache, M.; Boz, I.; Pădurariu, C.; Burzo, I.; Badea, M.; Toma, C.; Galeş, R.; Olteanu, Z.; Truţă, E.; et al. Comparative research regarding the chemical composition of essential oils from some Lamiaceae taxa. Bul. AŞM Biotehnol. Veg. Anim. 2010, 2, 161–165. [Google Scholar]

- Duman, A.D.; Telci, I.; Dayisoylu, K.S.; Digrak, M.; Demirtas, İ.; Alma, M.H. Evaluation of bioactivity of linalool-rich essential oils from Ocimum basilicum and Coriandrum sativum varieties. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2010, 5, 969–974. [Google Scholar]

- Orav, A.; Arak, E.; Raal, A. Essential oil composition of Coriandrum sativum L. fruits from different countries. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2011, 14, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsagkli, A.; Hancianu, M.; Aprotosoaie, A.C.; Cioanca, O.; Tzakou, O. Volatile constituents of Romanian coriander fruit. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2012, 6, 156–160. [Google Scholar]

- Camelia, O.; Antonia, O.; Csaba Pal, R.; Ioan, O.; Iulia, C.M.; Marcel, D.; Marioara, I.; Ioan, B.; Cristian, I.; Zamfir, M. Composition of Lavandula angustifolia L. cultivated in Transylvania, Romania. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2019, 47, 643–650. [Google Scholar]

- Lafontaine, E.R.; Cope, L.D.; Aebi, C.; Latimer, J.L.; McCracken, G.H.; Hansen, E.J. The UspA1 protein and a second type of UspA2 protein mediate adherence of Moraxella catarrhalis to human epithelial cells in vitro. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 1364–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirth, T.; Morelli, G.; Kusecek, B.; van Belkum, A.; van der Schee, C.; Meyer, A.; Achtman, M. The rise and spread of a new pathogen: Seroresistant Moraxella catarrhalis. Genome Res. 2007, 17, 1647–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vries, S.P.; Bootsma, H.J.; Hays, J.P.; Hermans, P.W. Molecular aspects of Moraxella catarrhalis pathogenesis. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2009, 73, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiniger, N.; Spaniol, V.; Troller, R.; Vischer, M.; Aebi, C. A reservoir of Moraxella catarrhalis in human pharyngeal lymphoid tissue. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 196, 1080–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsgren, A.; Brant, M.; Möllenkvist, A.; Muyombwe, A.; Janson, H.; Woin, N.; Riesbeck, K. Isolation and characterization of a novel IgD-binding protein from Moraxella catarrhalis. J. Immunol. 2001, 167, 2112–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, M.M.; Vanlerberg, S.L.; Foley, I.M.; Sledjeski, D.; Lafontaine, E.R. The Moraxella catarrhalis porin-like outer membrane protein CD is an Adhesin for human lung cells. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 1906–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordström, T.; Blom, A.; Tan, T.T.; Forsgren, A.; Riesbeck, K. Ionic binding of C3 to the human pathogen Moraxella catarrhalis is a unique mechanism for combating innate immunity. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 3628–3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, T.F.; Parameswaran, G.I. Moraxella catarrhalis, a human respiratory tract pathogen. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 49, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlu-Ingok, A.; Catalkaya, G.; Capanoglu, E.; Karbancioglu-Guler, F. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of fennel, ginger, oregano and thyme essential oils. Food Front. 2021, 2, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines (EDQM). Chapter 5.4. Residual solvents (07/2018:50400). In European Pharmacopoeia, 10th ed.; European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines (EDQM): Strasbourg, France, 2021; Supplement 5. [Google Scholar]

| Species (Part Used) | Main Active Compounds | Romanian Traditional Indications |

|---|---|---|

| Allium cepa (bulb) | Organosulfur compounds, flavonoids, and phenolcarboxilic acids [17] | Cough, pharyngitis, laryngitis, rhinitis, cold, bronchitis [11,12,18] |

| Allium sativum (bulb) | Organosulfur compounds, flavonoids, and phenolcarboxilic acids [17] | Cough with sputa and puss, pharyngitis, laryngitis, rhinitis, cold [11,12,18] |

| Hyssopus officinale (aerial part) | Polyphenols, saponins, EO (monoterpenes) [17] | Cough, laryngitis, pneumonia, tuberculosis [11,18] |

| Juniperus communis (shoots, berries) | Polyphenols, EO (monoterpenes) [17] | Cold, rhinitis, cough, tuberculosis [11,18] |

| Lavandula angustifolia (flowers) | Flavonoids, phenolcarboxilic acids, EO (monoterpenes) [17] | Cough, upper respiratory tract infections [11,18] |

| Mentha x piperita (leaves, aerial parts) | Flavonoids, phenolcarboxilic acids, EO (monoterpenes) [17] | Cough, asthma, pulmonary emphysema, laryngitis, tonsillitis [11,18] |

| Ocimum basilicum (aerial parts) | Flavonoids, phenolcarboxilic acids, EO (monoterpenes) [17] | Cough, cold, tuberculosis [11,18] |

| Origanum vulgare | Flavonoids, phenolcarboxilic acids, EO (monoterpenes) [17] | Asthma, pneumonia, bronchitis [11,18] |

| Pynus sylvestris (shoots) | Flavonoids, EO (monoterpenes) [17] | Tuberculosis, asthma [11,18] |

| Salvia officinalis (leaves) | Flavonoids, phenolcarboxilic acids, EO (monoterpenes) [17] | Tonsilitis, rhinitis, laryngitis, emphysema [11,12,18] |

| Thymus vulgaris (aerial parts) | Flavonoids, EO (monoterpenes) [17] | Cough [11] |

| Tilia cordata (flowers) | Mucilages, flavonoids, EO (sesquiterpenes) [19] | Cough, cold, emphysema, asthma, bronchitis, pneumonia [11,18] |

| Verbascum phlomoides (flowers) | Mucilages, flavonoids, iridoids [19] | Emphysema, asthma, tuberculosis, pharyngitis, pneumonia, cough, rhinitis [11,18] |

| Bacterial Strain | Herbal Material/Source | Testing Sample | MIC/DIZ/Inhibition % | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | ||||

| CWL-029 | Mentha arvenisisR (aerial parts)/Finland | ME | 90% at 256 μg/mL | [32] |

| K7 (clinical isolate) | Schisandra chinensis (fruits)/Estonia | ME | <100 μg/mL | [33] |

| America | ||||

| AR39 | Hydrocotyle bonariensis (aerial parts), Lithraea molleoides (leaves), Hybanthus parviflorus (aerial parts)/Argentina | AqE, DcmE, ME Ethanol/water (1:1) extracts | 50–90% DcmE of Hydrocotyle bonariensis (aerial parts) is the most active | [34] |

| Others | ||||

| K7 (clinical isolate) | 27 peppermint R teas /unspecified origin | AqE | 20.7–69.5% at 250 μg/mL | [35] |

| CWL-029 | Unspecified | 32 betulinic derivatives | Betulin: 53% at 1 μM Betulin-28-oxime: 100% at 1 μM Betulin-3,28-dioxime: 100% at 1 μM and 50% at 290 nM | [36] |

| Bacterial Strain | Herbal Material/SOURCE | Testing Sample | MIC/DIZ/Inhibition % | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | ||||

| PCM2340 | Rubus idaeusR “Willamette”cultivar (shoots)/Poland | ME | >120 mg/mL (resistant) | [37] |

| ATCC 49247, Amp-R1, AMP-R2 | Betula aetnensis (leaves)/Greece | ME | 900 μg/mL (for ATCC 49247, Amp-R1), 1800 μg/mL (for Amp-R2) | [38] |

| Africa | ||||

| clinical isolate | Tilia cordataR (bracts and flowers)/Lebanon | AqE *, ME * | 20–22 mm (flowers AqE), 0 mm (bracts AqE, AlEs) | [39] |

| ATCC 35056 | Medicago sativaR (root)/Iran | ME | 125 mg/mL | [40] |

| clinical isolates (7 strains) | Eucalyptus globulus (leaves)/Iran | ME * | MIC50 = 16 mg/L, MIC90 = 32 mg/L | [41] |

| clinical isolates | Ammi majus (seeds)/Oman | ME HF, CF, EaF, BF, AqF | 0 mm (ME) 6–9 mm (fractions) | [42] |

| clinical isolates (12 strains) | Trichilia emetica (root)/Mali | AqE DeeF | >500 μg/mL (AqE) 125 μg/mL (DeeF) | [43] |

| clinical isolates (11 strains) | 8 species of the genus Eucalyptus (leaves)/Tunisia | EO | 8.1 ± 2.2 mm–19.2 ± 9.6 mm | [44] |

| America | ||||

| ATCC 49247, 90-CCH-02 | Ceanothus coereleus (roots), Chrysactinia mexicana (flowers, roots), Cordia boissieri (leaves), Phyla nodiflora (leaves), Schinus mole (bark, fructs, roots)/Mexico | AqE, HE, DeeE, ME | ≥500 μg/mL (all) | [45] |

| Others | ||||

| unspecified | Echinacea. AngustifoliaR (root), E. purpurea R (root+aerial parts), E. purpurea R (root)/unspecified origin | Liquid AlE (48% alcohol, 40% alcohol) *; Dry AlE (0% alcohol) | AlE (40% alcohol) > AlE (48% alcohol) AlE (0% alcohol)—inactive | [46] |

| DSM 9143 | Unspecified | EO of Syzygium aromaticum, Cinnamomum zeylanicum, Eucalyptus globulus, Thymus vulgaris R, Pinus sylvestris R, Mentha × piperita R, Cymbopogon nardus | By broth microdilution test: 0.25 mg/mL (Syzygium aromaticum), 0,06 mg/mL (Cinnamomum zeylanicum), 1.41 mg/mL (Eucalyptus globulus), 0.11 mg/mL (Thymus vulgaris) 1.35 mg/mL (Pinus sylvestris) 0.41 mg/mL (Mentha × piperita), 125 mg/mL (Cymbopogon nardus) By vapor phase test 250 μL/L (Syzygium aromaticum), 75 μL/L (Cinnamomum zeylanicum), >1500 μL/L (Eucalyptus globulus), 125 μL/L (Thymus vulgaris) >1500 μL/L (Pinus sylvestris) 250 μL/L (Mentha × piperita), 125 μL/L (Cymbopogon nardus) | [28] |

| Bacterial Strain | Herbal Material/Source | Testing Sample | MIC Value/DIZ/Inhibition % | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | ||||

| ATCC 700603 | 14 species of Rumex genus R (different parts)/Carpathian Basin (Hungary and Romania). | ME HE, CF, AqF | 10–15 mm (R. acetosa, R. alpinus, R. crispus, R. aquaticys–root CF), <10 mm (others) | [29] |

| clinical isolates | 8 aromatic plants: Hyssopus officinalis R, Achillea grandifolia, Achillea crithmifolia R, Tanacetum partheniu R, Laserpitium latifolium, Angelica sylvestris, Angelica pancicii, Artemisia absinthium R (aerial parts)/Sebia. | ME * | 5.0 mg/mL (Hyssopus officinalis), 25.0 mg/mL (Achillea grandifolia) 2.5 mg/mL (Achillea crithmifolia) 25 mg/mL (Tanacetum partheniu) 25 mg/mL (Laserpitium latifoliu) 50 mg/mL (Angelica sylvestris) 50 mg/mL (Angelica pancici) 50 mg/mL (Artemisia absinthium) MBC > 100 mg/mL(all) | [47] |

| unspecified | 65 species from Italy flora (including Origanum vulgare R) | AlE | <4.0 μg/mL (Origanum vulgare) Others-inactive | [48] |

| clinical isolates | Rubus idaeusR “Willamette” cultivar (shoots)/Poland | ME | 60 mg/mL | [37] |

| ATCC 13882 | Thymus vulgarisR (aerial parts)/Romania | EO | 30–34 mm | [49] |

| clinical isolates (16 strains) | Origanum vulgare subsp. Hirtum R, Salvia officinalis R, Thymus vulgaris R (aerial parts)-irrigated and non-irrigated plants/Greece | EO | irrigated//non-irrigated plants: 73 mg/L//103 mg/L (Origanum vulgare subsp. hirtum) 240 mg/L//207.4 mg/L (Salvia officinalis) 9.5 mg/L//11.3 mg/L (Thymus vulgaris) | [50] |

| Africa | ||||

| unspecified | Medicago sativaR. (seeds)/Egypt | ME * | 10 → 20 mm, depending on origin | [51] |

| clinical isolate | Momordica charantia (leaves and fruits)/Tanzania | ME, PeE | 12–13 mm (leaves PeE), 18 mm (fruits ME), <10 mm (others) | [52] |

| clinical isolate | Cnestis ferruginea (leaf)/Nigeria | AqE *, AlE *, ME * | 150 mg/mL (AqE) 20 mg/mL (AlE) 350 mg/mL (ME) | [53] |

| ATCC 13883 | Warburgia salutaris (bark, leaves)/South Africa | ME *, DcmE * | 1.0 mg/mL (bark MEs and DcmEs) 0.66 mg/mL (leaves EO) 0.50–0.83 mg/mL (bark EOs) 0.312 mg/mL (E-nerolidol) 0.13–0.208 mg/mL (other compounds) | [54] |

| ampicillin-resistant strain (unspecified) | Curtisia dentata (stem bark, leaves)/South Africa | ME | 156.25 μg/mL (stem bark) 312.5 μg/mL (leaves) | [55] |

| ATCC 13883 | Xylopia aethiopica, Eriosema glomeratum, other 16 plants (leaves)/Cameroon | Methanol-dichloromethane (1:1) extracts | 250 μg/mL (Xylopia aethiopica) 500 μg/mL (Eriosema glomeratum) 1000–> 8000 μg/mL (Others) | [56] |

| ATCC 13883 | Alchornea cordifolia (stems and leaves)/Cameroon | AlE, CE, EaE, ME | ≤125 μg/mL (all extracts) 16 μg/mL (Methylgallate) | [27] |

| ATCC 13883 | Alchornea floribunda (stems and leaves)/Cameroon | AlE, CE, EaE, ME | ≤125 μg/mL (all extracts) | [57] |

| clinical isolate | Ocimum sanctum (leaves), Eugenia caryophyllata (flowers), Achyranthes bidentata (stem, leaves), Azadirachta indica (stem and bark)/Nepal | AlE * | All: <6 mm | [58] |

| clinical isolate | Tilia cordataR (bracts and flowers)/Lebanon | AqE *, ME * | 0 mm (AqEs, MEs) | [39] |

| ATCC 700603 | Carum copticum (unspecified part)/Iran | AlE, ME | 12 mm (AlE), 20 mm (ME) 25 mg/mL (AlE, ME) | [59] |

| clinical isolates | Tribulus terrestrisR (fruits, leaves, roots)/Iraq | AqE, AlE, CE | 0.31 mg/mL (leaves AlE) >5 mg/mL (roots AqE) 1.25. or 2.5 mg/mL (others) | [60] |

| ATCC 13883 | Punica granatum (leaves, flowers)/South Africa | AqE | 9–14 mm (leaves), 8–14 mm (flowers), depending on the concentration (50–5000 μL/mL) | [61] |

| ATCC 10031 | Eucalyptus largiflorens, E. intertexta (leaves)/Iran | ME CF, AqF EO | 10 mm (AqF), 15–20 mm (EO), 20 mm (1,8-cineol) 125 mg/mL (ME), 7.8–125 mg/mL (EO), 500 mg/mL (1,8-cineol) | [62] |

| clinical isolate | Origanum syriacum, Thymus syriacus, Syzygium aromaticum, Cinnamomum zeylanicum, Laurus nobilis, Juniperus foetidissima, Allium sativumR, Myristica fragrans (leaves, bulbs, barks, aerial parts, rhizome, flowers, seeds, fruits)/Syria | AlE EO | MIC50//MIC90 6.25 μL/mL//no effect (Origanum syriacum) 6.25 μL/mL//no effect (Thymus syriacus) 1.5 μL/mL//25 μL/mL (Syzygium aromaticum) 3.125 μL/mL//no effect (Cinnamomum zeylanicum) 6.25 μL/mL//12.5 μL/mL (Laurus nobilis) 12.5 μL/mL//25 μL/mL (Juniperus foetidissima) 6.25 μL/mL//50 μL/mL (Allium sativum) 6.25 μL/mL//no effect (Myristica fragrans) | [63] |

| unspecified | Ocimum basilicumR (aerial parts)/Oman | EO | resistant | [64] |

| unspecified | Thymus capitatus (aerial parts)/Libya | EO | 4.0–5.0 mm | [65] |

| unspecified | Salvia lachnocalyx, S. mirzayanii and S. sahendica (aerial parts)/Iran | EO | 10 mm | [66] |

| NCTC 9633 | Artemisia afra (leaves and stems), Agathosma betulina (leaves), Eucalyptus globulus (leaves), Osmitopsis asteriscoides (leaves)/South Africa | EO | 9.3 mg/mL (Artemisia afra—leaves and stem) 16 mg/mL (Agathosma betulina-leaves), 8.0 mg/mL (Eucalyptus globulus-leaves), 8.0 mg/mL (Osmitopsis asteriscoides-leaves) | [67] |

| clinical isolates (13 strains) | 8 species of the genus Eucalyptus (leaves)/Tunisia | EO | 6.6–10.8 mm, depending on origin | [44] |

| ATCC 13883 | Leptospermum petersonii, L. scoparium, Kunzea ericoides (aerial parts)/South Africa | EO | 8.0 mg/mL (all EOs) | [68] |

| Asia | ||||

| ATCC 4352 | Anethum graveolensR (aerial parts, leaves, seeds)/Turkey | Aerial parts EO Seed EO | 3.13%–12.5% (aerial parts EO), 0.8–12.5% (seed EO) | [69] |

| ATCC 4352 | Verbascum xanthophoeniceum, V. densiflorumR, V. lagurus V. gnaphalodes, V. phlomoidesR (aerial parts)/Turkey | ME * CF *, EaF *, PeF *, TF*, AqF * | 312.5 μg/mL (V. lagurus EaF) >1250 μg/mL (others) | [70] |

| unspecified | 5 medicinal plants: Boerhaavia diffusa, Cassiaauriculata, Cassia lantana, Eclipta alba, Tinospora cardiofolia (leaves)/India | AqE ME | Boerhaavia diffusa: 10 mm (AqE, ME), Cassia auriculata, Cassia Lantana: 0 mm (AqE, ME), Eclipta alba: 9 mm (AqE), 16 mm (AlE),Tinospora cardiofolia: 8 mm (AqE), 13 mm (AlE) | [71] |

| unspecified | 6 folk medicinal plants in India: Eugenia jambolana (kernel), Cassia auriculata (flowers) Murraya koenigii (leaves), Salvadora persica (stem) and Ipomoea batatas (leaves) and Andrographis paniculata (leaves)/India. | ME | Andrographis paniculate: 8 mm (at 2 mg/mL)–12 mm (at 4 mg/mL) Eugenia jambolana: 7 mm (at 2 mg/mL)–12 mm (at 4 mg/mL) Cassia auriculata: 9 mm (at 2 mg/mL)-12 mm (at 4 mg/mL) Other species and its extracts: <6 mm | [30] |

| ATCC 10273 | Acacia melifera (whole plant)/India | HE *, EaE *, ME *, AlE * | 18 mm (ME), 0 mm (other extracts) | [72] |

| ATCC 4030 | Alysicarpus vaginalis (root)/India | AqE, CE, ME, PeE | 10 mm (AqE, PeE), 11 mm (CE), 12 mm (ME) 6.25 mg/mL (ME) | [73] |

| NCIM2719 | 23 species belonging to 21 different families (leaves, stem)/India | AcE, ME | 8–21 mm | [74] |

| unspecified | Pogostemon benghalensis (leaves)/India | AqE, ME | 0 mm (AqE–cold water), 8–12 mm (AqE-hot water), <8 mm (ME-cold methanol), >12 mm (ME-hot methanol) | [75] |

| clinical isolates | 26 ayurvedic plants (different parts)/Bangladesh | Extracts (unclear specified) | 8–21 mm, depending on species and bacterial isolates: 10–17 mm (Allium sativum-bulb), 9–13 mm (Allium cepa-bulb), 8–10 mm (Nigella sativa-seeds), 9–21 mm (Citrus limonum–fruits) s.a. | [76] |

| clinical isolates | Coriandrum sativumR (seeds), Brassica alba R (seeds), Mentha arvensis R (leaves), Ocimum basilicum R (leaves), Terminalia bellirica (fruits), Illicium verum (fruits), Hyptis suaveolens (seeds), Vetiveria zizanioides (roots), Myristica fragrans (fruits), Sesamum indicum (seeds), Piper nigrum (fruits), Curcuma longa (rhizome)/Bangladesh | AlE, EaE, HE | 187.5 μg/mL (Coriandrum sativum seeds AlE) 375 μg/mL (Brassica alba seeds EaE and HE) 750 μg/mL (Mentha arvensis leaves AlE) 750 μg/mL (Ocimum basilicum leaves HE) 187.5 μg/mL (Terminalia bellirica fruits EaE), 93.7 μg/mL (Terminalia bellirica fruits AlE) 375 μg/mL (Illicium verum fruits EaE and HE), 1500 μg/mL (Illicium verum fruits EaE) 375 μg/mL (Hyptis suaveolens seeds HE) >1500 μg/mL (Vetiveria zizanioides roots HE) 375 μg/mL (Myristica fragrans fruits HE), 1500 μg/mL (Myristica fragrans fruits AlE and EaE) 375 μg/mL (Sesamum indicum seeds HE) 375 μg/mL (Piper nigrum fruits HE and EaE) 375 μg/mL (Curcuma longa rhizomes HE) | [77] |

| ATTC 13883 | 6 non-indigenous medicinal plants naturalized in Malaysia: Ailanthus triphysa, Clinacanthus nutans, Gynostemma pentaphyllum, Gynura bicolor, Turnera subulata (leaves), Asystasia gangetica (aerial parts) | AlE, AqE, CE, EaE, HE, ME | AqEs–inactive 2.5 mg/mL (Ailanthus triphysa leaves AlE and ME), 2.5 mg/mL (Clinacanthus nutans leaves AlE); Clinacanthus nutans leaves ME-inactive, 1.25 mg/mL (Gynostemma pentaphyllum AlE); Gynostemma pentaphyllum ME-inactive, 1.25 mg/mL (Gynura bicolor AlE); Gynura bicolor ME-inactive, 2.5 mg/mL (Turnera subulata leaves AlE and ME) 1.25 mg/mL (Asystasia gangetica aerial parts AlE), 0.63 mg/mL (Asystasia gangetica aerial parts ME) | [78] |

| MTCC-432 | Ocimum basilicumR (leaves)/India | EO | 15 μg/mL | [79] |

| NCIM 2957 | Ocimum basilicumR (flowering aerial parts)/India | EO | MBC = 1.875 mg/mL | [80] |

| ATCC 15380 | Unspecified | EOs/India (market) | 3.2 mg/mL (Cinnamom EO) >6.4 mg/mL (Clove EO) 12.8 mg/mL (Geranium EO, Orange EO) >12.8 mg/mL (Lemon EO, Rosemary EO) | [31] |

| America | ||||

| unspecified | Ocimum basilicumR (leaves, stems and flowers)/Brazil | EO | 12.2 mm 0.75 mg/mL | [81] |

| Others | ||||

| ATCC 13883 | Coriandrum sativumR (seeds)/unspecified origin | EO | 0.2% | [82] |

| ATCC 700603 | Unspecified | EOs | 5 mg/mL (Peppermint R EO) 20 mg/mL (Eucalyptus EO) 10 mg/mL (Cajuput EO, Wintergreen EO) 40 mg/mL (Juniper R Berry EO) | [83] |

| unspecified | Allium sativumR (bulbs)/(unclear specified) | AqE, CE, EaE, HE, ME | 12 mm (ME), 17 mm (AqE), <10 mm (others) 150 μg/mL (ME), 100 μg/mL (AqE) | [84] |

| ATCC 700603 | Unspecified | Curcumin | 216 μg/mL | [85] |

| Bacterial Strain | Herbal Material/Source | Testing Sample | MIC value/DIZ/inhibition % | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europa | ||||

| ATCC 25238 | Betula aetnensis (leaves)/Greece | ME | 220 μg/mL | [38] |

| ATCC 43617 | 14 species of Rumex genus R (different parts)/Carpathian Basin (Hungary and Romania). | ME AqF, CF, HF | R. aquaticusR (roots, aerial parts), R. crispus R (aerial parts), R. patienta R (flowers), R. stenophyllus R (flowers), R. thypsiflorusR (roots): >10 mm (AqF), others: <10 mm | [29] |

| ATCC 43617 | 4 bryophyte species (Amblistegium serpens, Plagiomnium cuspidatum, Rhytidium rugosum, Schistidium crassipilum)/Hungary | AqE, ME CF, HF | 9.0 mm (Amblistegium serpens CF) 10.0 mm (Plagiomnium cuspidatum HF) 7.5 mm (Rhytidium rugosum CF) 7.7 mm (Schistidium crassipilum CF) | [86] |

| ATCC 25238 | Thymus capitatus (leaves)/Italy | ME HF, MF | 62.5 μg/mL (MF) >1000 μg/mL (others) | [87] |

| ATCC 25238 | Helleborus bocconei subsp. siculus (root)/Italy | ME | 0.4 mg/mL | [88] |

| PCM 2340 | Rubus idaeusR (3 cultivars), Rubus occidentalis (1 cultivar) (fruits)/Poland | AlE | 2–8 mg/mL (extracts) 0.015 mg/mL (elagic acid) | [89] |

| PCM2340 | Rubus idaeusR “Willamette” cultivar (shoots)/Poland | ME | 0.5 mg/mL | [37] |

| Africa | ||||

| ATCC 23246 | Warburgia salutaris (bark)/South Africa | DcmE *, ME * EO | 0.42 mg/mL (DcmE), 2.0. mg/mL (ME) 0.5–1.0 mg/mL (EO) 0.031 mg/mL (E-nerolidol) | [54] |

| ATCC 25240 | Punica granatum (leaves, flowers)/South Africa | AqE * | 8.9–14 mm (leaves), 12.0–15.33 mm (flowers); depending to the concentration (50–5000 μL/mL) | [61] |

| ATCC25240 | Medicago sativaR (root)/Iran | ME | 16 mm 125 mg/mL | [40] |

| ATCC 23246 | Artemisia afra (leaves and stems), Agathosma betulina (leaves), Eucalyptus globulus (leaves), Osmitopsis asteriscoides (leaves)/South Africa | EO | 8 mg/mL (all) | [67] |

| ATCC 23246 | Leptospermum petersonii, L. scoparium, Kunzea ericoides (aerial parts)/South Africa | EO | 4 mg/mL (Leptospermum petersonii), 2 mg/mL (L. scoparium), 8 mg/mL (Kunzea ericoides) | [68] |

| ATCC 23246 | Citrus limon (leaves), Eucalyptus grandis (leaves), Helichrysum kraussii (leaves and stem), Lippia javanica (leaves), Tetradenia riparia (leaves)/South Africa | EO | 13.33 mg/mL (Citrus limon-leaves), 4.0 mg/mL (Eucalyptus grandis-leaves), 5.33 mg/mL (Helichrysum kraussii-leaves and stem), 5.33 mg/mL (Lippia javanica-leaves), 5.33 mg/mL (Tetradenia riparia-leaves) | [90] |

| ATCC 14468 | 18 species Alchornea floribunda (leaves) Musanga cecropioides (leaves and stem bark) Tetracera potatoria, Xylopia aethiopica (stem barks)/South Africa | Methanol—dichloromethane (1:1) extracts | 65 μg/mL (Alchornea floribunda-leaves), 130 μg/mL (Musanga cecropioides-leaves and stem bark) 250 μg/mL (Tetracera potatoria–stem bark), 250 μg/mL (Xylopia aethiopica-stem bark) >1000 μg/mL (others) | [56] |

| clinical isolates | Trichilia emetica (root)/Mali | AqE EeF | >500 μg/mL (AqE), 7.8–31.2 μg/mL (EeF) | [43] |

| clinical isolates | Allium sativumR (bulbs), Cinnamomum zeylanicum (bark), Syzygium aromaticum (buds), Persea americana (leaves), Rosmarinus officinalis (leaves), Argemone mexicana (leaves)/Ethiopia | AlE *, AqE *, ME * | 15.0 mm (Allium sativum AqE), 11.0 mm (Cinnamomum zeylanicum AlE), 11.0 mm (Persea americana ME), no inhibition (others). 30 mg/mL (Allium sativum AqE), 20 mg/mL (Cinnamomum zeylanicum AlE), 30 mg/mL (Persea americana ME), no inhibition (others) | [91] |

| unspecified | Curtisia dentata (leaves)/South Africa | AcE, AlE, CE, EaE | 6.25 mg/mL (AlE), 1.57 mg/mL (CE), 3.13 mg/mL (AcE and EaE) 0.3 mg/mL (betulinic acid) 1.25 mg/mL (ursolic acid) 3.13 mg/mL (lupeol) 1.25 mg/mL (β-sitosterol) | [92] |

| ATCC 23246, | Alchornea cordifolia (roots, stems and leaves)/Cameroon | AqE, AlE, CE, HE, ME | 125 μg/mL (AlEs and MEs) >1000 μg/mL(others) | [27] |

| ATCC 23246 | Alchornea floribunda (roots, stems and leaves)/Cameroon | AqE, AlE, CE, HE, ME | 250 μg/mL (roots AlEs and MEs) 500 μg/mL (leaves AlEs and MEs) 1000 μg/mL (stems AlEs and MEs) | [57] |

| Others | ||||

| DSM 9143 | Unspecified | EOs of Syzygium aromaticum, Cinnamomum zeylanicum, Eucalyptus globulus, Thymus vulgaris R, Pinus sylvestris R, Mentha × piperita R, Cymbopogon nardus | By broth microdilution 0.25 mg/mL (Syzygium aromaticum) 0.10 mg/mL (Cinnamomum zeylanicum) 2.81 mg/mL (Eucalyptus globulus), 0.09 mg/mL (Thymus vulgaris) 1.34 mg/mL (Pinus sylvestris) 0.35 mg/mL (Mentha × piperita) 0.11 mg/mL (Cymbopogon nardus) By vapor phase test 125 μL/L (Syzygium aromaticum) 25 μL/L (Cinnamomum zeylanicum) 225 μL/L (Eucalyptus globulus) 50 μL/L (Thymus vulgaris) >1500 μL/L (Pinus sylvestris) 31.25 μL/L (Mentha × piperita) 25 μL/L (Cymbopogon nardus) | [28] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duțu, L.E.; Popescu, M.L.; Purdel, C.N.; Ilie, E.I.; Luță, E.-A.; Costea, L.; Gîrd, C.E. Traditional Medicinal Plants—A Possible Source of Antibacterial Activity on Respiratory Diseases Induced by Chlamydia pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Moraxella catarrhalis. Diversity 2022, 14, 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14020145

Duțu LE, Popescu ML, Purdel CN, Ilie EI, Luță E-A, Costea L, Gîrd CE. Traditional Medicinal Plants—A Possible Source of Antibacterial Activity on Respiratory Diseases Induced by Chlamydia pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Moraxella catarrhalis. Diversity. 2022; 14(2):145. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14020145

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuțu, Ligia Elena, Maria Lidia Popescu, Carmen Nicoleta Purdel, Elena Iuliana Ilie, Emanuela-Alice Luță, Liliana Costea, and Cerasela Elena Gîrd. 2022. "Traditional Medicinal Plants—A Possible Source of Antibacterial Activity on Respiratory Diseases Induced by Chlamydia pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Moraxella catarrhalis" Diversity 14, no. 2: 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14020145

APA StyleDuțu, L. E., Popescu, M. L., Purdel, C. N., Ilie, E. I., Luță, E.-A., Costea, L., & Gîrd, C. E. (2022). Traditional Medicinal Plants—A Possible Source of Antibacterial Activity on Respiratory Diseases Induced by Chlamydia pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Moraxella catarrhalis. Diversity, 14(2), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14020145