Abstract

Heretofore, the populations of the genus Sphaerotheca Günther, 1859 (Dicroglossidae) in their northern and western borders laying in Pakistan have been assigned to two species, S. breviceps (Schneider, 1799) and S. strachani (Murray, 1884). The genus originated in the Oriental zoogeographic region and comes to close geographic proximity with the Palearctic region in Pakistan. The recent molecular studies have on one hand restricted the distribution range of S. breviceps to the eastern coastal plains of India and, on the other hand, revealed the northern- and westernmost population in India as a separate species, S. pashchima Padhye et al., 2017. This species has recently been synonymized with S. maskeyi (Schleich and Anders, 1998). These taxonomic changes, however, warranted the need for validation of Pakistani Sphaerotheca based on genetic data. We sequenced and analyzed 16S rRNA mitochondrial gene from specimens originating from the Himalayan foothills of Pakistan and compared these with all available GenBank sequences of the genus. Based on this data, we conclude that the Himalayan foothills of Pakistan are occupied by S. maskeyi. Simultaneously, we bring the first record of this species for the Palearctic region. We further suggest that more genetic material from across Pakistan is required to ascertain the validity of S. strachani and for the phylogeographic evaluation of western and northern border populations of the genus. Our geographically wide and revisited molecular phylogeny shows that the genus exhibits genetic diversity suggesting further taxonomic changes. The low level of genetic divergences between S. breviceps and S. magadha Prasad et al., 2019 compared to other species of the genus, indicates that the taxonomic status of S. magadha is questionable. Moreover, we found that S. magadha and S. swani (Mayers and Leviton, 1956) are genetically conspecific with S. breviceps and both should be thus considered its junior synonyms. On the other hand, S. dobsonii and populations from Myanmar need further detailed investigations.

1. Introduction

The genus Sphaerotheca Günther, 1859 represents medium-sized frogs of the family Dicroglossidae and comprises currently ten morphologically similar taxa distributed in Pakistan, India, Nepal, Bhutan, Myanmar, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and probably Maldives [1]. In Pakistan, they are known from the Hab and Malir River valleys in Karachi, the Himalayan foothills and Potwar Plateau, and the Cholistan Desert [2,3]. The genus originated in the Oriental zoogeographical region and the territory of Pakistan represents the northern- and westernmost limit of the overall range of the genus [2,3]. Sphaerotheca frogs have high species diversity in the Indian subcontinent [4] and, due to descriptions of various taxa, changing taxonomy, and high genetic diversity with an unclear distribution, they are objects of several studies [5,6,7,8].

The species status of the genus in the Pakistani territory (the northern and western range borders) is unclear with the presumption that these populations are not conspecific to the species reported from the country. Khan [2] and Masroor [3] mentioned the taxon Sphaerotheca breviceps (Schneider, 1799) for the Pakistani territory with its type locality in Tranquebar, Tamil Nadu, India [9]. Moreover, Pakistan is also known to harbor S. strachani (Murray, 1884) from the type locality Sindh (Mulleer = Malir, near Karachi), with so far, unclear taxonomic status. However, the overall distribution and the diversity of the genus based on genetic data from India and Nepal suggest that the Pakistani populations should not be assigned under previously mentioned taxa [4,5,7,8]. Therefore, we bring the first genetic data of the genus Sphaerotheca from northern Pakistan (Figure 1) to provide arguments for its genetic affiliation that could resolve the taxonomy. Simultaneously, our most updated and revised phylogeny of the genus provides a novel view on relationships among these frogs with further taxonomic consequences.

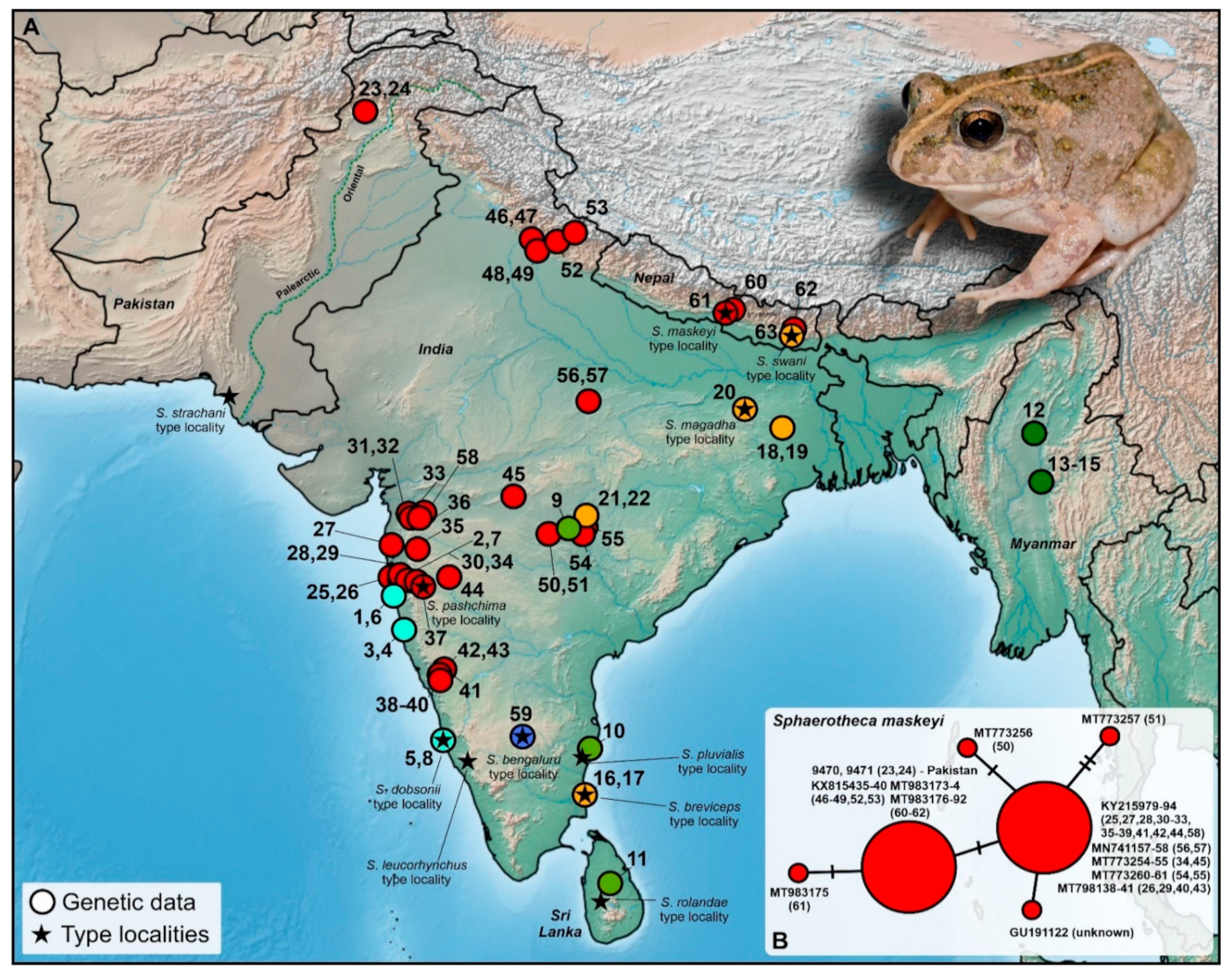

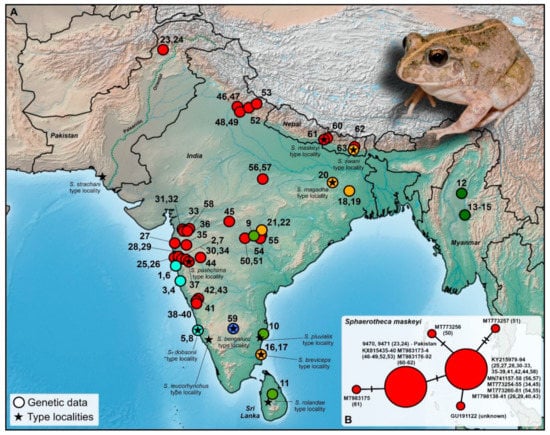

Figure 1.

The external morphological color variation of Sphaerotheca maskeyi from Pakistan: (A) Shah Alam Baba (adult; DJ 9471 used in this study); (B) Batai Kalay, Qadir Nagar River, Buner (subadult); (C) Parera, Chakwal; (D) Kotli, Azad and Jammu Kashmir (subadult); (E) Shakarparian, Islamabad (adult); (F) Margalla Hills National Park (juvenile).

2. Materials and Methods

Two adult specimens (DJ9470-71) were collected in mid-September 2019 during a night survey in Shah Alam Baba, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, Pakistan (34.73° N, 72.09° E, 883 m a.s.l. and 34.72° N, 79.10° E, 1013 m a.s.l., respectively; Figure 1 and Figure 2). These frogs were found in the agricultural area close to the direction of a dry river valley. The specimens were photographed alive (Nikon D810, and 105 mm macro lens) and subsequently euthanized and preserved in 70% ethanol. Before preservation, a tongue was taken as a tissue sample and transferred into 96% ethanol, kept at ambient temperature during the time of the fieldwork, and later stored at −20 °C.

Figure 2.

(A) Map displaying the localities of genetically covered (16S rRNA) populations of the genus Sphaerotheca. (B) Median-joining haplotype network showing the intraspecific relationships of S. maskeyi with regard to Pakistani populations. Colors correspond to phylogenetic groups shown in Figure 3. The depicted individual originates from Shah Alam Baba, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province (DJ9470), Pakistan. Details to the locality numbers are listed in the Supplementary Table S1.

DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Tissue Kit (QIAGEN) following the manufacturer’s protocols. A fragment of the mitochondrial 16S region (~600 bp) was amplified using the primers 16sar (5′-CGCCTGTTTATCAAAAACAT-3′) and 16br (5′-CCGGTCTGAACTCAGATCACGT-3′). Purified PCR products were sequenced in both directions by Macrogen (Amsterdam, the Netherlands). Sequences were revised manually and aligned along with sequences from the NCBI GenBank based on their secondary structures using RNAsalsa 0.8.1 [10] and the ribosomal structure model of Bos taurus downloaded from www.zfmk.de/en/research/research-centres-and-groups/rnasalsa (accessed on 1 March 2021) (for GenBank accession numbers, see Supplementary Table S1).

To reconstruct the phylogeny of the genus Sphaerotheca, we included all available 16S sequences from the NCBI GenBank database (~560 bp; Table S1) and made maximum-likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) trees using RAxML v.8.2.12 [11] and MrBayes v.3.2.6 [12], respectively. We ran RAxML with the GTRGAMMA model and 1000 bootstrap replicates. In the Bayesian analysis, we assigned the doublet model (16 × 16) proposed by [13] to the rRNA stem regions. For this procedure, unambiguous stem pairs were derived based on the consensus structure from RNAsalsa and specified in the MrBayes input file. For the analysis of the remaining positions, the standard 4 × 4 option was applied using a GTR evolutionary model. MrBayes was run for 15 million generations, with four parallel Markov chain Monte Carlo simulations and four chains (one cold and three heated), sampling trees every 500th generation and using a random tree as a starting point. Inspection of the standard deviation of split frequencies after the final run as well as the effective sample size value of the traces using Tracer v. 1.7.1 [14] indicated convergence of Markov chains. The first 25% of the samples of each run were discarded as burn-in. Based on the sampled trees, a consensus tree was produced using the sumt command in MrBayes. To support the tree phylogeny and show phylogenetic clustering of defined clades, we performed a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) based on allelic data (as frequencies) of the same dataset we used for tree analysis (without outgroups) using R package Adegenet [15] implemented in the R statistical environment [16]. Prior to the PCA, missing data were replaced by “NA”.

To assess the evolutionary distance between our samples and the Sphaerotheca clades recovered from the phylogenetic analysis, uncorrected p-distances were calculated between the clades using Mega-X v.11.0 [17] with the pairwise deletion option, 1000 bootstrap replications, and by considering both transitions and transversions.

Finally, a median-joining haplotype network was created with PopART [18].

3. Results

Mitochondrial 16S rRNA data confirmed that both the analyzed sequences from the Pakistani territory cluster with the clade associated to S. maskeyi (Schleich and Anders, 1998) (Figure 2 and Figure 3). This represents the first published record of the species from the Palearctic region and the first-ever published and genetically supported record for the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, Pakistan. This clade is distributed from western, central, and northeastern India, and Nepal with the northwestern-most recorded distribution in Pakistan (Figure 2A). It forms a genetically diversified clade, showing significant intra-clade variability (Figure 3). However, this variability is not high (0.28%; Figure 2B, Table S2). The haplotype network also showed little variation within sequences of S. maskeyi, whereas Pakistani sequences share the haplotype with populations of the species from northern India and Nepal. This haplotype is separated by only one mutation step from the central haplotype of all other investigated populations of S. maskeyi (Figure 2B).

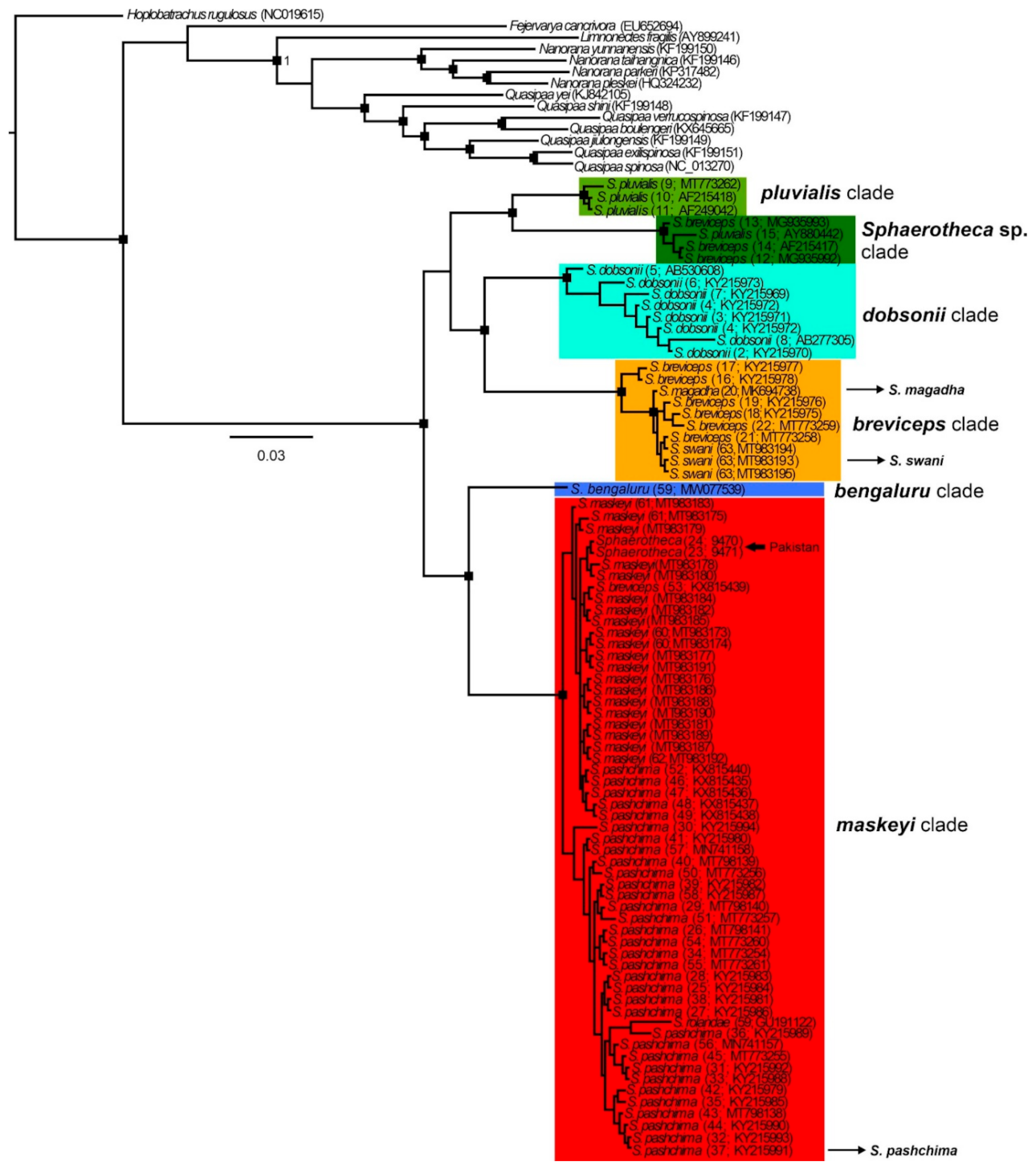

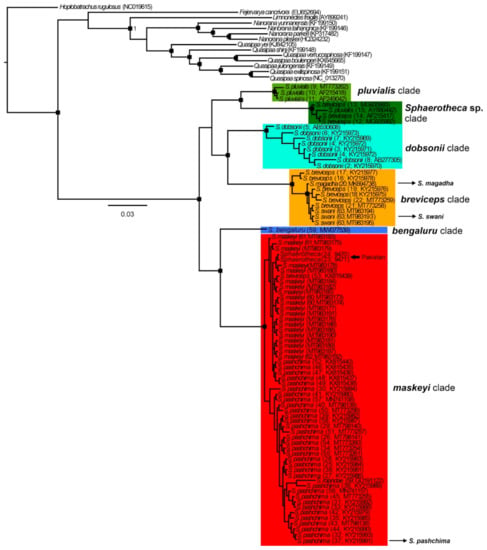

Figure 3.

Bayesian inference tree of the genus Sphaerotheca based on 16S rRNA (~600 bp) sequence data. Rectangles at branch nodes refer to posterior probabilities ≥0.95. For maximum-likelihood trees, see supplementary Figure S1. The details on the geographic distribution of detected clades can be seen in Figure 2.

Overall, in the 16S phylogenies (ML and BI) of the analyzed sequences, we detected six well-supported phylogenetic clades, named as follows (Figure 3, Figures S1 and S2): breviceps, distributed across southern, central, and northeastern India and Nepal which includes the taxa S. breviceps, S. magadha Prasad et al., 2019 and S. swani (Mayers and Leviton, 1956) and their type localities; maskeyi, from western, central, and northeastern India, Pakistan and Nepal, including from type localities of S. pashchima Padhye et al., 2017 and S. maskeyi; pluvialis, from Sri Lanka (close to the type locality of S. rolandae (Dubois, 1983)) and southern and central India; Sphaerotheca sp., from Myanmar, probably representing an unknown taxon (p-distance more than 7% from other clades; Table 1); dobsonii from the western Indian coast; bengaluru, represented by sequence data from the type locality of S. bengaluru Deepak et al., 2020 (Table 1, Figure 3 and Figures S1 and S2)). The topology of the studied sequences is similar in both analyses, but it is not well-resolved in the ML tree (see the position of S. dobsonii in Figure S1). In the BI tree, two main groups of clades are inferred, forming sister position (i) pluvialis + Sphaerotheca sp. + dobsonii + breviceps, and (ii) bengaluru + maskeyi. These detected sequence groups (except Sphaerotheca sp.) present an admixed phylogeographic pattern (Figure 2). The highest number of clades was found in central and southern India and their overall interclade genetic p-distances reached more than 10% (Table 1 and Table S2). The resulting topology and clade support (Figure 3 and Figure S1) confirmed the validity of the following species: S. bengaluru, S. breviceps, S. dobsonii, S. maskeyi, and S. pluvialis. In accordance with the detected phylogeny, the PCA analysis revealed six distinct clusters (Figure S2), with S. dobsonii showing a sequence out of the confidence interval. The sequence with accession number GU191122 from GenBank, which had been assigned as S. rolandae, is nested in the clade of S. maskeyi (genetic distance ~1%, Table 1) and is apparently erroneously identified as S. maskeyi. Sequences of S. magadha and S. swani (breviceps clade) formed an intra-clade lineage of S. breviceps with a p-distance of less than 2% and should be thus treated as its junior synonyms. Similarly, according to our analysis, the recently described S. pashchima is conspecific with S. maskeyi.

Table 1.

Uncorrected genetic distances (%) between investigated Sphaerotheca sequences as shown in Figure 1. Given are p-distance values for 16S mitochondrial gene (lower-left) and standard error estimates (upper-right). The complete pairwise p-distance matrix is presented in Supplementary Table S2.

4. Discussion

Herein, we provide a mitochondrial phylogeny and the first genetic data of the genus Sphaerotheca from Pakistan. We found that the population inhabiting the Himalayan foothills is assigned to S. maskeyi and, for the first time, we provide evidence for the presence of the species in the Palearctic region (Figure 2) and in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan (although the collection of the Pakistan Museum of Natural History contains specimens from Mardan [PMNH 171] and Mansehra [PMNH 2160] of that province, collected before this study). The distribution and genetic pattern of S. maskeyi clade provide indications in support of a possible colonization through the Indian subcontinent with the northernmost geographic limits in Pakistan. If true, this would be in contrast with the Oriental genus Microhyla (Microhylidae), which is limited, according to the current knowledge, only to Oriental parts of Pakistan [19]. On the other hand, both these genera show a similar phylogeographic pattern displaying low genetic variability in river plains of northern Indian subcontinent. This might be the result of missing geographic barriers in the lowlands of northern India and southeastern Pakistan as previously suggested [2,19]. However, current sampling remains insufficient to draw final conclusions on the biogeography of S. maskeyi but urges further studies for a future understanding of the species’ evolutionary history.

In the literature, two taxa of the genus have been reported from Pakistan, i.e., S. breviceps and S. strachani. The former has been reported from the Oriental part of the Himalayan foothills, Cholistan desert, and around Karachi [2], whereas the latter only from southern Pakistan [20]. The widely distributed species S. breviceps has long been considered a species complex [9,21]. Consequently, the western Indian population of the genus Sphaerotheca from Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Karnataka has been recently described as S. pashchima [5]. These authors also suggested the presence of this taxon in the state of Rajasthan. Recent molecular studies have thus unraveled the long-standing mystery in restricting the distribution range of S. breviceps to the east coastal plains of India [4,7]. However, a new study [8] from the material originating from type localities of two taxa from Nepal (S. maskeyi, S. swani) showed that S. pashchima is conspecific with S. maskeyi and thus this former taxon should be its junior synonym. From the viewpoint of Pakistani localities, the northern limit of the distribution range of S. maskeyi has now extended from Dehradun, Uttarakhand, in the Himalayan foothills [7], to northwestern Pakistan and eastern Nepal, whereas the species’ southwestern limit is restricted to the region in Maharashtra and Gujarat, where it needs further confirmation [4,7].

The other little-known taxon (S. strachani) was described from Mulleer (Malir), Sindh, Pakistan [20]. Although Murray [22] was inclined to assign his specimens to S. breviceps, he was later convinced to describe them as S. strachani based on several morphological characteristics including the short longitudinal plaits on the back and the fold across the body behind the forelegs. Although several studies suggest that the taxon S. strachani is a synonym of S. breviceps [2,9,20,23], the validity of the taxon S. strachani and its possible distributional boundaries should be tested through genetic data. Nevertheless, according to current data, S. maskeyi is the species that has the westernmost distribution reaching close to the Himalayan foothills and the Sindh region of Pakistan (see the map in [3] and Figure 2 in this study). Since there are no major geographical barriers between western Indian records of S. maskeyi and the type locality of S. strachani around Karachi (see Figure 2A), we rather expect that S. strachani could be a phenotypic variant of S. maskeyi. The external variation is known throughout populations of the species range [7,8] and Figure 1 in this study. However, genetic material from Karachi, as well as other parts of southern Pakistan and northwestern India, will be of great importance in ascertaining the specific status of S. strachani.

A high level of genetic distances was detected between the clades, suggesting the existence of unrecognized taxa (e.g., Sphaerotheca sp., Figure 3). On the other hand, the GenBank sequence of S. rolandae (GU191122), which clusters within the maskeyi clade, was probably morphologically misidentified with S. maskeyi, originating from the unknown locality of India. The type locality of S. rolandae is in Kurunegala, Sri Lanka, and there are no records of this species from the Indian subcontinent (e.g., [4,7]). The recently described S. magadha [6] and S. pashchima [5] represent the intraspecific variability of S. breviceps and S. maskeyi, respectively (see Figure 3 and Figure S1, ~1–2% in p-distances, Table 1, Table S2). Thus, in the molecular phylogenetic context and regarding the genetic distances of other members of the genus, these taxa, including S. swani (breviceps clade), should not be considered separate species [8]. However, the genus requires further integrative research.

Given the current taxonomy of the genus and the fact that some species and populations might be threatened, especially near mountain ranges or at the edge of the distribution range (e.g., Pakistan), a thorough taxonomic revision—including a wide DNA sampling covering all taxa and coupled with morphological and bioacoustic data—is needed to better understand species delineation and their geographic distribution.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/d13050216/s1, Figure S1: Maximum-likelihood tree of the genus Sphaerotheca with main detected clades. The details on the geographic distribution of detected clades can be seen in Figure 2. Colors corresponds with clades shown in Figure 3. Rectangles at branch nodes refer to bootstrap values ≥75. Figure S2: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of defined clades of Sphaerotheca genus with suggested taxonomic affiliation showing inter- and intraclade distances. The oval outlines in PCA represent 95% confidence intervals. First (PC1) and second (PC2) principal components explain 18.4% and 13.9% of the observed variance. Table S1: List of Sphaerotheca species used in the present study, including sample ID or voucher numbers, sample localities, and GenBank accession numbers. For the locality identifier see Figure 1. Coordinates are given in decimal degrees. § = sample of photographed specimen (see Figure 1). NCBI = National Center for Biotechnology Information. Table S2: Complete pairwise p-distance matrix for all samples used in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.J. and S.H.; methodology, all authors; analysis, D.J., S.H.; investigation, D.J., R.M. and S.H.; resources, all authors; data curation, all authors; writing—original draft preparation, D.J. and S.H.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, D.J. and S.H.; funding acquisition, D.J. and S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the German Science Foundation (DFG), grant number HO 3792/8-1 to SH and by the Slovak Research and Development Agency under contract no. APVV-19-0076 to DJ.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the regulations for the protection of terrestrial wild animals under the permits of the Pakistan Museum of Natural History, Islamabad, Pakistan.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The new sequence data presented in this study (DJ9470, DJ9471) are openly available in GenBank under the accession numbers MW676044 and MW676045, respectively.

Acknowledgments

We thank Muhammad Idrees for his help in the field, and Jana Poláková for her assistance with laboratory work. We also thank three anonymous reviewers that improved the first version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Frost, D.R. Amphibian Species of the World: An Online Reference Version 6.0 Electronic Database. American Museum of Natural History, New York. Available online: http://research.amnh.org/herpetology/amphibia/index.html (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Khan, M.S. Amphibians and Reptiles of Pakistan; Krieger Publishing Company: Malabar, FL, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-089-464-952-3. [Google Scholar]

- Masroor, R. A Contribution to the Herpetology of Northern Pakistan: The Amphibians and Reptiles of Margalla Hills National Park and Surrounding Regions; Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles: New York, NY, USA; Chimaira Buchhandelsgesellschaft mbH: Frankfurt, Germany, 2012; ISBN 978-091-698-483-0. [Google Scholar]

- Deepak, P.; Dinesh, K.P.; Prasad, K.V.; Das, A.; Ashadevi, J.S. Distribution status of the Western Burrowing Frog, Sphaerotheca pashchima in India. Zootaxa 2020, 4894, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padhye, A.; Dahanukar, N.; Sulakhe, S.; Dandekar, N.; Limaye, S.; Jamdade, K. Sphaerotheca pashchima, a new species of burrowing frog (Anura: Dicroglossidae) from western India. J. Threat. Taxa 2017, 9, 10286–10296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, V.K.; Dinesh, K.P.; Das, A.; Swamy, P.; Shinde, A.D.; Vishnu, J.B. A new species of Sphaerotheca Gunther, 1859 (Amphibia: Anura: Dicroglossidae) from the agro ecosystems of Chota Nagpur Plateau, India. Rec. Zool. Surv. India 2019, 119, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandekar, N.; Sulakhe, S.; Padhye, A. Range extension of the western burrowing frog, Sphaerotheca pashchima (Anura: Dicroglossidae), in Central and Northern India, with an overview of the distribution of other Indian species in the genus Sphaerotheca. Reptiles Amphib. 2020, 27, 390–396. [Google Scholar]

- Khatiwada, J.R.; Wang, B.; Zhao, T.; Xie, F.; Jiang, J. An integrative taxonomy of amphibians of Nepal: An updated status and distribution. Asian Herpetol. Res. 2021, 12, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, A. Note préliminaire sur le groupe de Rana (Tomopterna) breviceps Schneider, 1799 (Amphibiens, Anoures), avec diagnose d’une sous-expèce nouvelle de Ceylan. Alytes 1983, 2, 163–170. [Google Scholar]

- Stocsits, R.R.; Letsch, H.; Hertel, J.; Misof, B.; Stadler, P.F. Accurate and efficient reconstruction of deep phylogenies from structured RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 6184–6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML Version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; van der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoniger, M.; von Haeseler, A. Toward assigning helical regions in alignments of ribosomal RNA and testing the appropriateness of evolutionary models. J. Mol. Evol. 1999, 49, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rambaut, A.; Drummond, A.J.; Xie, D.; Baele, G.; Suchard, M.A. Posterior Summarization in Bayesian Phylogenetics Using Tracer 1.7. Syst. Biol. 2018, 67, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jombart, T. Adegenet: A.R. package for the multivariate analy sis of genetic markers. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 1403–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing 2020. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leigh, J.W.; Bryant, D. PopART: Full-feature software for haplotype network construction. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2015, 6, 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonski, D.; Khan, M.A.; Masroor, R. The genus Microhyla (Anura: Microhylidae) in Pakistan: Species status and origins. Zootaxa 2020, 4845, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minton, S.A. A contribution to the herpetology of West Pakistan. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 1966, 134, 27–184. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, S.K. Comments on the species status and distribution of Tomopterna dobsonii Boulenger (Anura: Ranidae) in India. Rec. Zool. Surv. India 1986, 83, 123–127. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, J.A. The Vertebrate Zoology of Sind: A Systematic Account, with Descriptions of All the Known Species of Mammals, Birds, and Reptiles Inhabiting the Province, Observations on Their Habits, & c., Tables of Their Geographical Distribution in Persia, Beloochistan, and Afghanistan, Punjab, North-West Provinces, and the Peninsula of India Generally; Richardson & Co.: London, UK; Education Society’s Press: Bombay, India, 1884. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, R. Die Amphibien und Reptilien West-Pakistans. Stuttg. Beiträge zur Nat. 1969, 197, 1–96. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).