Generation Z Young People’s Perception of Sexist Female Stereotypes about the Product Advertising in the Food Industry: Influence on Their Purchase Intention

Abstract

:1. Introduction

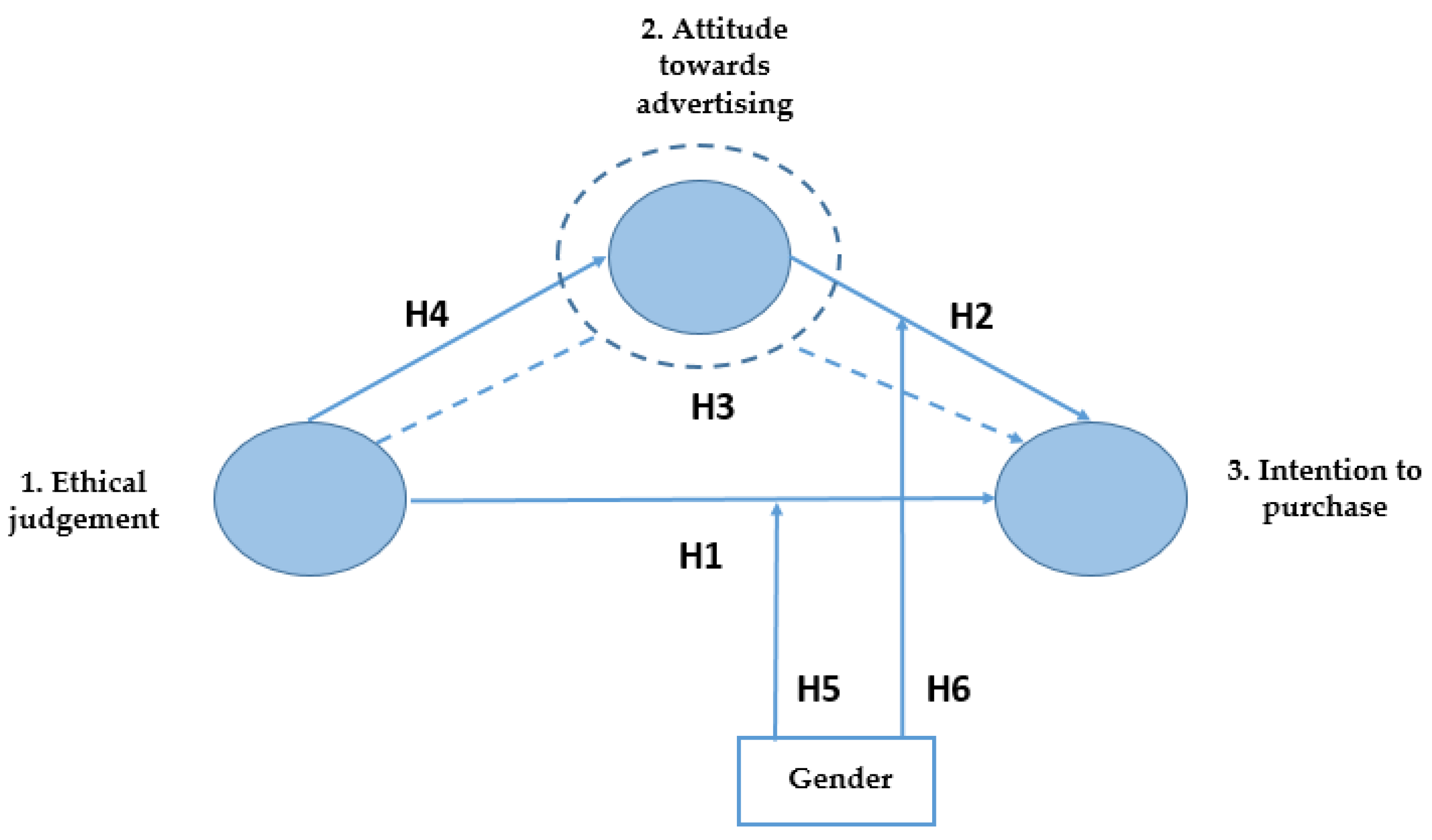

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Generation Z

2.2. Perception of Gender Stereotypes in Food and Drink Advertising

2.3. The Influence of Ethical Judgment on the Intention to Purchase the Product and the Effect of Attitude toward Sexist Advertising on the Intention to Purchase the Product

2.3.1. Direct and Indirect Influence of Ethical Judgment toward Sexist Advertising on Purchase Intention

2.3.2. Influence of the Attitude toward Sexist Advertising on the Purchase Intention

2.3.3. Influence of Ethical Judgment on the Attitude toward Sexist Advertising

3. Data Collection and Method

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analyses of the Observed Variables

4.2. Results of Hostile Sexism Video’s Model (Video 1) and Benevolent Sexism Video’s Model (Video 2)

4.2.1. Measurement Models

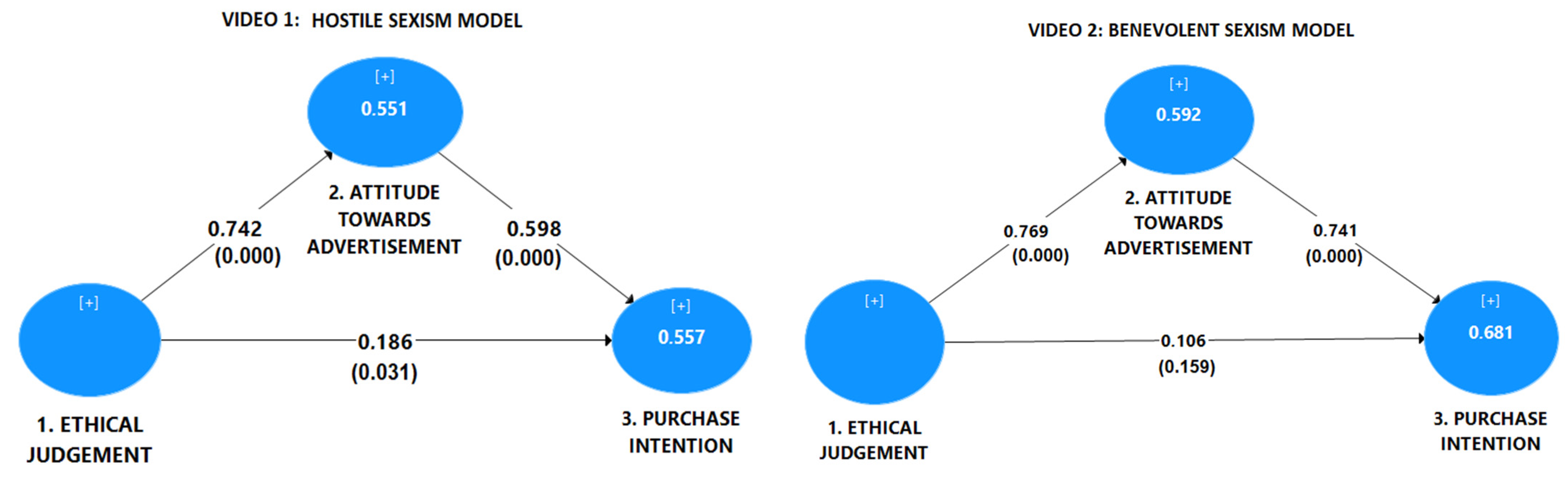

4.2.2. Structural Models

5. Discussions and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Browne, B.A. Gender stereotypes in advertising on children’s television in the 1990s: A cross-national analysis. J. Advert 1998, 27, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, N. The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used against Women; Random House: Barcelona, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Furnham, A.; Li, J. Gender portrayal in food and beverage advertisements in Hong Kong: A content analytic study. Young Consum. 2008, 9, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerin, R.A.; Lundstrom, W.J.; Sciglimpaglia, D. Women in advertisements: Retrospect and prospect. J. Advert. 1979, 8, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plakoyiannaki, E.; Mathioudaki, K.; Dimitratos, P.; Zotos, Y. Images of women in online advertisements of global products: Does sexism exist? J. Bus. Ethics. 2008, 83, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, P.; Fiske, S.T. The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 491–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biefeld, S.D.; Stone, E.A.; Brown, C.S. Sexy, thin, and white: The intersection of sexualization, body type, and race on stereotypes about women. Sex Roles 2021, 85, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisend, M. A meta-analysis of gender roles in advertising. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2010, 38, 418–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawisza, M.; Luyt, R.; Zawadzka, A.M.; Buczny, J. Does it pay off to break male gender stereotypes in cross-national ads? A comparison of ad effectiveness between the United Kingdom, Poland and South Africa. J Gend Stud. 2016, 27, 464–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito-Rhor, M.D.; Rodríguez-Herráez, B.; Chachalo-Carvajal, G.P. Does the intensity of sexual stimuli and feminism influence the attitudes of consumers toward sexual appeals and ethical judgment? An ecuadorian perspective. Rev. Comun. La SEECI 2019, 48, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zawisza, M.; Luyt, R.; Zawadzka, A.M.; Buczny, J. Cross-cultural sexism and the effectiveness of gender (non) traditional advertising: A comparison of purchase intentions in Poland, South Africa, and the United Kingdom. Sex Roles 2018, 79, 738–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remafedi, G. Study group report on the impact of television portrayals of gender roles on youth. J. Adolesc. Health Care 1990, 11, 59–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.C.; Page, R.A. Marketing to the generations. J. Behav. Bus. 2011, 3, 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, E.; Lee, C. A workforce to be reckoned with: The emerging pivotal Generation Z hospitality workforce. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 73, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz, C.L. Generations X, Y, and Z. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2019, 44, A7–A8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Csobanka, Z.E. The Z Generation. Acta Technol. Dubnicae 2016, 6, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Băltescu, C.A. Elements of tourism consumer behaviour of generation Z. Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Brasov. Econ. Sci. 2019, 12, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priporas, C.V.; Stylos, N.; Fotiadis, A.K. Generation Z consumers’ expectations of interactions in smart retailing: A future agenda. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 77, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.J.; Lu, W. Bloomberg News Gen Z is Set to Outnumber Millennials Within a Year. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-08-20/gen-z-to-outnumber-millennials-within-a-year-demographic-trends (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Joshi, R.; Garg, P. Role of brand experience in shaping brand love. Int. J. Consum. 2021, 45, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffett, R. The YouTube Marketing Communication Effect on Cognitive, Affective and Behavioural Attitudes among Generation Z Consumers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatto, B.; Erwin, K. Moving on From Millennials: Preparing for Generation Z. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2016, 47, 253–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, E.B. The Millennial/Gen Z Leftists Are Emerging: Are Sociologists Ready for Them? Sociol. Perspect. 2020, 63, 408–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magano, J.; Silva, C.; Figueiredo, C.; Vitória, A.; Nogueira, T.; Pimenta Dinis, M.A. Generation Z: Fitting Project Management Soft Skills Competencies—A Mixed-Method Approach. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, L.Z.; Resko, B.G. The portrayal of men and women in American television commercials. J. Soc. Psychol. 1975, 97, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daalmans, S.; Kleemans, M.; Sadza, A. Gender Representation on Gender-Targeted Television Channels: A Comparison of Female-and Male-Targeted TV Channels in the Netherlands. Sex Roles 2017, 77, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Knoll, S.; Eisend, M.; Steinhagen, J. Gender roles in advertising: Measuring and comparing gender stereotyping on public and private TV channels in Germany. Int. J. Advert. 2011, 30, 867–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, G.; Furnham, A. The Universality of the portrayal of gender in television advertisements: An East-West comparison. Psychology 2016, 7, 1608–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsichla, E.; Zotos, Y. Gender portrayals revisited: Searching for explicit and implicit stereotypes in Cypriot magazine advertisements. J. Advert. 2016, 35, 983–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mager, J.; Helgeson, J. Fifty years of advertising images. Sex Roles 2011, 64, 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, A.; Furnham, A. Age and sex stereotypes in British television advertisements. Psychol. Popul. Media Cult. 2013, 2, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensa, M.; Bittner, V. Portraits of women: Mexican and Chilean stereotypes in digital advertising. Commun. Soc. 2020, 33, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.P.; Stayman, D.M. Antecedents and consequences of attitude toward the ad: A meta-analysis. J. Consum. Res. 1992, 19, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. The Will to Knowledge: The History of Sexuality; Penguin: London, UK, 1998; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Glick, P.; Fiske, S.T. An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zotos, Y.C.; Lysonski, S. Gender Representations: The Case of Greek Magazine Advertisments. Journal of Euromarketing. Eur. J. Mark. 1994, 3, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfhag, K.; Linné, Y. Gender differences in associations of eating pathology between mothers and their adolescent offspring. Obes. Res. 2005, 13, 1070–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Camusso, M. Cocinar y comer: Continuidades y rupturas en las representaciones sexogenéricas en publicidades de alimentos. RIVAR 2019, 6, 6–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronovsky, A.; Furnham, A. Gender portrayals in food commercials at different times of the day: A content analytic study. Communications 2008, 33, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, O.B. The weighty issue of Australian television food advertising and childhood obesity. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2006, 17, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lull, R.; Bushman, B. Does sex and violence sell? A metaanalytic review of the effects of sexual and violent media and ad content on memory, attitudes, and buying intentions. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 1022–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodd, H.D.; Patel, V. Content analysis of children’s television advertising in relation to dental health. Br. Dent. J. 2005, 199, 710–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, S.; Dehkordi, G.J.; Rahman, M.S.; Fouladivanda, F.; Habibi, M.; Eghtebasi, S. A conceptual study on the country of origin effect on consumer purchase intention. Asian Soc. Sci. 2012, 8, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brunk, K.H. Exploring origins of ethical company/brand perceptions—A consumer perspective of corporate ethics. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imtiyaz, H.; Soni, P.; Yukongdi, V. Investigating the Role of Psychological, Social, Religious and Ethical Determinants on Consumers’ Purchase Intention and Consumption of Convenience Food. Foods 2021, 10, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, A.; Kaeck, D.L. Ethical Judgment of Food Fraud. Effects on Consumer Behavior. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2019, 25, 605–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Seaton, B. Emerging consumer orientation, ethical perceptions, and purchase intention in the counterfeit smartphone market in China. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2015, 27, 27–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, P.M.; Brown, G.; Widing, R.E. The association of ethical judgment of advertising and selected advertising effectiveness response variables. J. Bus. Ethics. 1998, 17, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, H.D.; Wiese, M.D.; Bruce, M.L. When retailers target women based on body shape and size: The role of ethical evaluation on purchase intention. J. Consum. Res. 2018, 33, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.Q.; Kanjanamekanant, K. No trespassing: Exploring privacy boundaries in personalized advertisement and its effects on ad attitude and purchase intentions on social media. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 103314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.; Paek, H. Predicting cross-cultural differences in sexual advertising contents in a transnational woman´s magazine. Sex Roles 2005, 53, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, T. Sex in advertising research: A review of content, effects, and functions of sexual information in consumer advertising. Annu. Rev. Sex Res. 2002, 13, 241–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, S. The Ethics of Food Production and Regulation of “Misbranding”. Available online: http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:8965624 (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Graff, S.; Kunkel, D.; Mermin, S.E. Government can regulate food advertising to children because cognitive research shows that it is inherently misleading. Health Aff. 2012, 31, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Grougiou, V.; Balabanis, G.; Manika, D. Does Humour Influence Perceptions of the Ethicality of Female-Disparaging Advertising? J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 164, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido, G.; Prete, M.I.; Peluso, A.M.; Maloumby-Baka, R.C.; Buffa, C. The role of ethics and product personality in the intention to purchase organic food products: A structural equation modeling approach. Int. Rev. Econ. 2010, 57, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalz, S.; Orth, U.R. Brand attachment and consumer emotional response to unethical firm behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2012, 29, 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, D.M.; Paas, L.J. Moderately thin advertising models are optimal, most of the time: Moderating the quadratic effect of model body size on ad attitude by fashion leadership. Mark. Lett. 2014, 25, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Lu, Y.; Wang, B. Customers’ purchase decision-making process in social commerce: A social learning perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamouda, M. Understanding social media advertising effect on consumers’ responses: An empirical investigation of tourism advertising on Facebook. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2018, 31, 426–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovici, D.; Marinov, M. Determinants and antecedents of general attitudes towards advertising: A study of two EU accession countries. Eur. J. Mark. 2007, 41, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.B.; Lee, S.G.; Yang, C.G. The influences of advertisement attitude and brand attitude on purchase intention of smartphone advertising. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 1011–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biehal, G.; Stephens, D.; Curio, E. Attitude toward the ad and brand choice. J. Advert. 1992, 21, 9–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, B.A.; Goldsmith, R.E.; Newell, S.J. The dual credibility model: The influence of corporate and endorser credibility on attitudes and purchase intentions. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2002, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, M.N.M.; Sreenivasan, J.; Ismail, H. Malaysian consumers attitude towards mobile advertising, the role of permission and its impact on purchase intention: A structural equation modeling approach. Asian Soc. Sci. 2013, 9, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, R.P.; Banerjee, N. Exploring the influence of celebrity credibility on brand attitude, advertisement attitude and purchase intention. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2018, 19, 1622–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, S.; Erdogan, B.Z. Özdeşleşmenin Reklama Karşı Tutum ve Satın Alma Niyeti Üzerindeki Etkisinde Ünlü-Ürün Uyumunun Ilımlaştırıcı Rolü/The Moderating Role of Celebrity-Product Match-up on the Effect of Identification on Attitude towards Advertising and Purchase Intention. Uni. J. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2020, 15, 603–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infanger, M.; Bosak, J.; Sczesny, S. Communality sells: The impact of perceivers’ sexism on the evaluation of women’s portrayals in advertisements. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konijn, E.A.; Hoorn, J.F. Some like it bad: Testing a model for perceiving and experiencing fictional characters. Media Psychol. 2005, 7, 107–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Churchill, G.A. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf-Psychologie-Arbeitsgruppen Allgemeine Psychologie und Arbeitspsychologie. GPower (Web Site). Available online: https://www.psychologie.hhu.de/arbeitsgruppen/allgemeine-psychologie-und-arbeitspsychologie/gpowerSoftwareGPower3version3.1.9.2forWindows (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analysis. Behav. Res. Methods. 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 1st ed.; Sage Publication, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Lutz, R.J.; Belch, G.E. The role of attitude toward the ad as a mediator of advertising effectiveness: A test of competing explanations. J. Mark. Res. 1986, 23, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.; Li, W.; Wang, V.L.; Guo, C. The impact of advertising self-presentation style on customer purchase intention. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2019, 32, 242–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; Version 25.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.M. Software “SmartPLS 3” (Version Professional 3.3.3, Update 2021). Boenningstedt. 2015. Available online: http://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Castillo-Apraiz, J.; Cepeda Carrion, G.; Roldán, J.L. Manual de Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Omnia Publisher SL: Barcelona, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences Mahwah; Lawrence Erlbaum: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.R.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Composite (Latent Variables) | Measures (Observed Variables or Indicators) | Seven-Point Likert Scale | Label |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ethical Judgement | How do you see the performance of the characters? | 1: Strongly incredible–7: Strongly credible | EJ1 |

| Brito-Rhor et al. [11] | How do you feel about the use of images? | 1: Strongly imprudent–7: Strongly prudent | EJ2 |

| How acceptable is it to you and your family? | 1: Strongly unacceptable–7: Strongly acceptable | EJ3 | |

| How does it seem to you morally? | 1: Strongly immoral–7: Strongly moral | EJ4 | |

| 2. Attitude toward Advertisement | Do you like the advertising? | 1: Totally dislike–7: Totally like | ATA1 |

| MacKenzie et al. [76] | What do you think about the advertising? | 1: Not appealing–7: Very appealing | ATA2 |

| Are you interested in the advertising? | 1: Not interesting–7: Very interesting | ATA3 | |

| Do you think the advertising is offensive? | 1: Not at all offensive–7: Very offensive | ATA4 | |

| 3. Purchase Intention of Food Product | Do you want to buy the product after seeing the advertisement? | 1: Not likely to buy–7: Very likely to buy | PI1 |

| Zeng et al. [77] | Would I be able to purchase the product after seeing this ad? | 1: Not likely to buy–7: Very likely to buy | PI2 |

| Coefficient (BCa Bootstrap 95%CI) | Sig. p-Value | Hypotheses | Type Mediation and VAF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Path | ||||

| H1 (1). Ethical judgment has a direct, positive influence on purchase intention (video 1). | 0.186 (0.020; 0.346) | * (0.031) | Supported | - |

| H2 (1). Attitude towards advertisement has a direct, positive influence on purchase intention (video 1). | 0.598 (0.465; 0.723) | *** (0.000) | Supported | - |

| H4 (1). Ethical judgment has a direct, positive influence on attitude towards advertisement (video 1). | 0.742 (0.659; 0.806) | *** (0.000) | Supported | - |

| Specific Indirect Path | - | |||

| H3 (1). Ethical judgement indirectly affects purchase intention through attitude towards advertisement (video 1). | 0.444 (0.353; 0.554) | *** (0.000) | Supported | VAF = 70.48% Partial collaborative mediation |

| Total = Direct + Indirect | - | |||

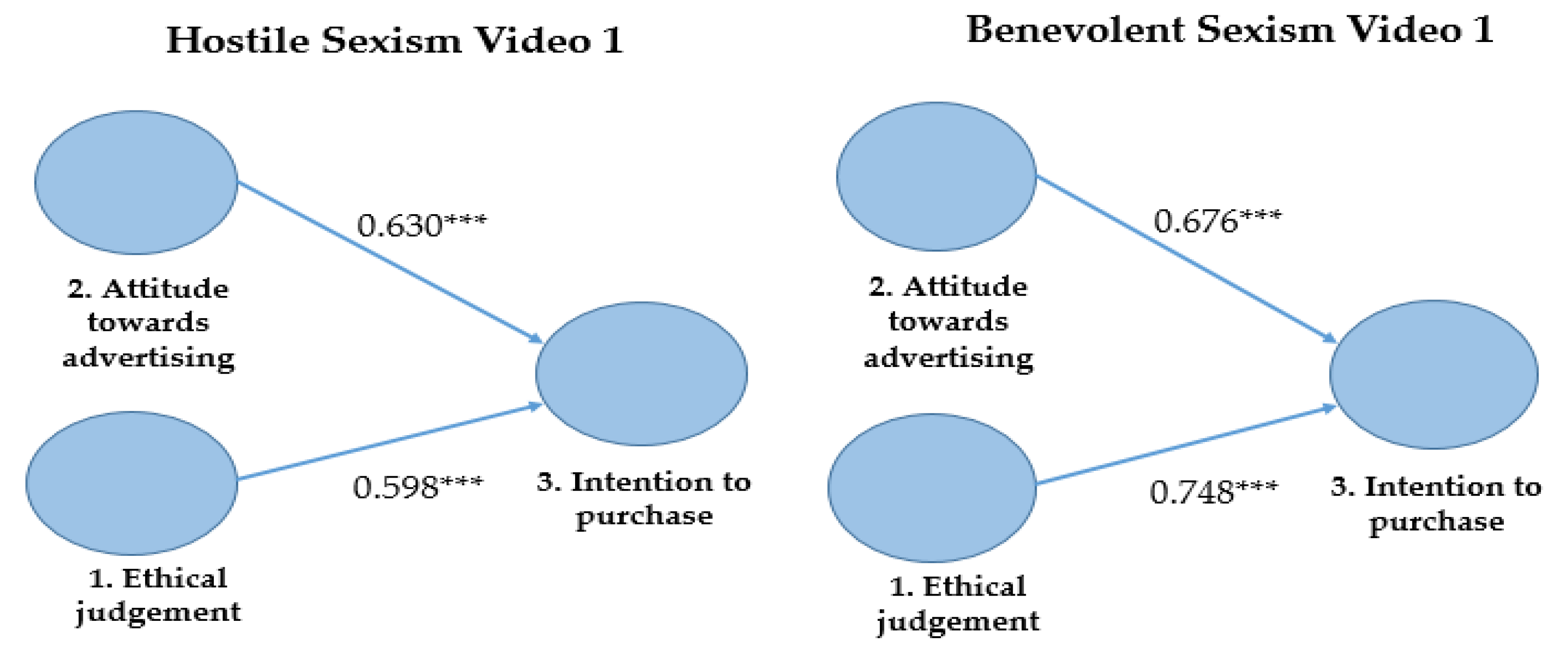

| H1 (1). Ethical judgment has a positive influence on purchase intention (video 1). | 0.630 (0.510; 0.719) | *** (0.000) | Supported | - |

| H2 (1). Attitude towards advertisement has a positive influence on purchase intention (video 1). | 0.598 (0.465; 0.723) | *** (0.000) | Supported | - |

| H4 (1). Ethical judgment has a direct, positive influence on attitude towards advertisement (video 1). | 0.742 (0.659; 0.806) | *** (0.000) | Supported | - |

| Coefficient (BCa Bootstrap 95%CI) | Sig. p-Value | Hypothesis | Type Mediation and VAF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Path | ||||

| H1 (2). Ethical judgment has a direct, positive influence on purchase intention (video 1). | 0.106 (−0.061; 0.292) | NS (0.159) | Rejected | |

| H2 (2). Attitude towards advertisement has a direct, positive influence on purchase intention (video 1). | 0.741 (0.564; 0.899) | *** (0.000) | Supported | |

| H4 (2). Ethical judgment has a direct, positive influence on attitude towards advertisement (video 1). | 0.769 (0.682; 0.832) | *** (0.000) | Supported | |

| Specific Indirect Path | ||||

| H3 (2). Ethical judgement indirectly affects purchase intention through attitude towards advertisement (video 1). | 0.570 (0.423; 0.736) | *** (0.000) | Supported | VAF = 84.32% Full collaborative mediation |

| Total = Direct + Indirect | ||||

| H1 (2). Ethical judgment has a positive influence on purchase intention (video 1). | 0.676 (0.585; 0.753) | *** (0.000) | Supported | |

| H2 (2). Attitude towards advertisement has a positive influence on purchase intention (video 1). | 0.741 (0.564; 0.899) | *** (0.000) | Supported | |

| H4 (2). Ethical judgment has a direct, positive influence on attitude towards advertisement (video 1). | 0.769 (0.682; 0.832) | *** (0.000) | Supported |

| Moderation | Coefficient (BCa Bootstrap 95%CI) | Sig. p-Value | Hypothesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| H5 (1). Gender moderates the relationship between attitude towards advertisement and purchase intention (video 1). | −0.000 (−0.103; 0.093) | NS (0.328) | Rejected |

| H6 (1). Gender moderates the relationship between ethical judgment and purchase intention (video 1). | 0.031 (0.022; 0.255) | NS (0.497) | Rejected |

| H5 (2). Gender moderates the relationship between attitude towards advertisement and purchase intention (video 2). | −0.031 (−0.131; 0.053) | NS (0.288) | Rejected |

| H6 (2). Gender moderates the relationship between ethical judgment and purchase intention (video 2). | −0.046 (−0.144; 0.035) | NS (0.201) | Rejected |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bermúdez-González, G.; Sánchez-Teba, E.M.; Benítez-Márquez, M.D.; Montiel-Chamizo, A. Generation Z Young People’s Perception of Sexist Female Stereotypes about the Product Advertising in the Food Industry: Influence on Their Purchase Intention. Foods 2022, 11, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11010053

Bermúdez-González G, Sánchez-Teba EM, Benítez-Márquez MD, Montiel-Chamizo A. Generation Z Young People’s Perception of Sexist Female Stereotypes about the Product Advertising in the Food Industry: Influence on Their Purchase Intention. Foods. 2022; 11(1):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11010053

Chicago/Turabian StyleBermúdez-González, Guillermo, Eva María Sánchez-Teba, María Dolores Benítez-Márquez, and Amanda Montiel-Chamizo. 2022. "Generation Z Young People’s Perception of Sexist Female Stereotypes about the Product Advertising in the Food Industry: Influence on Their Purchase Intention" Foods 11, no. 1: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11010053

APA StyleBermúdez-González, G., Sánchez-Teba, E. M., Benítez-Márquez, M. D., & Montiel-Chamizo, A. (2022). Generation Z Young People’s Perception of Sexist Female Stereotypes about the Product Advertising in the Food Industry: Influence on Their Purchase Intention. Foods, 11(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11010053