Atorvastatin Protects Against Deleterious Carfilzomib-Induced Transcriptional Changes in Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Validation of Pluripotent State Prior to Cardiomyocyte Differentiation

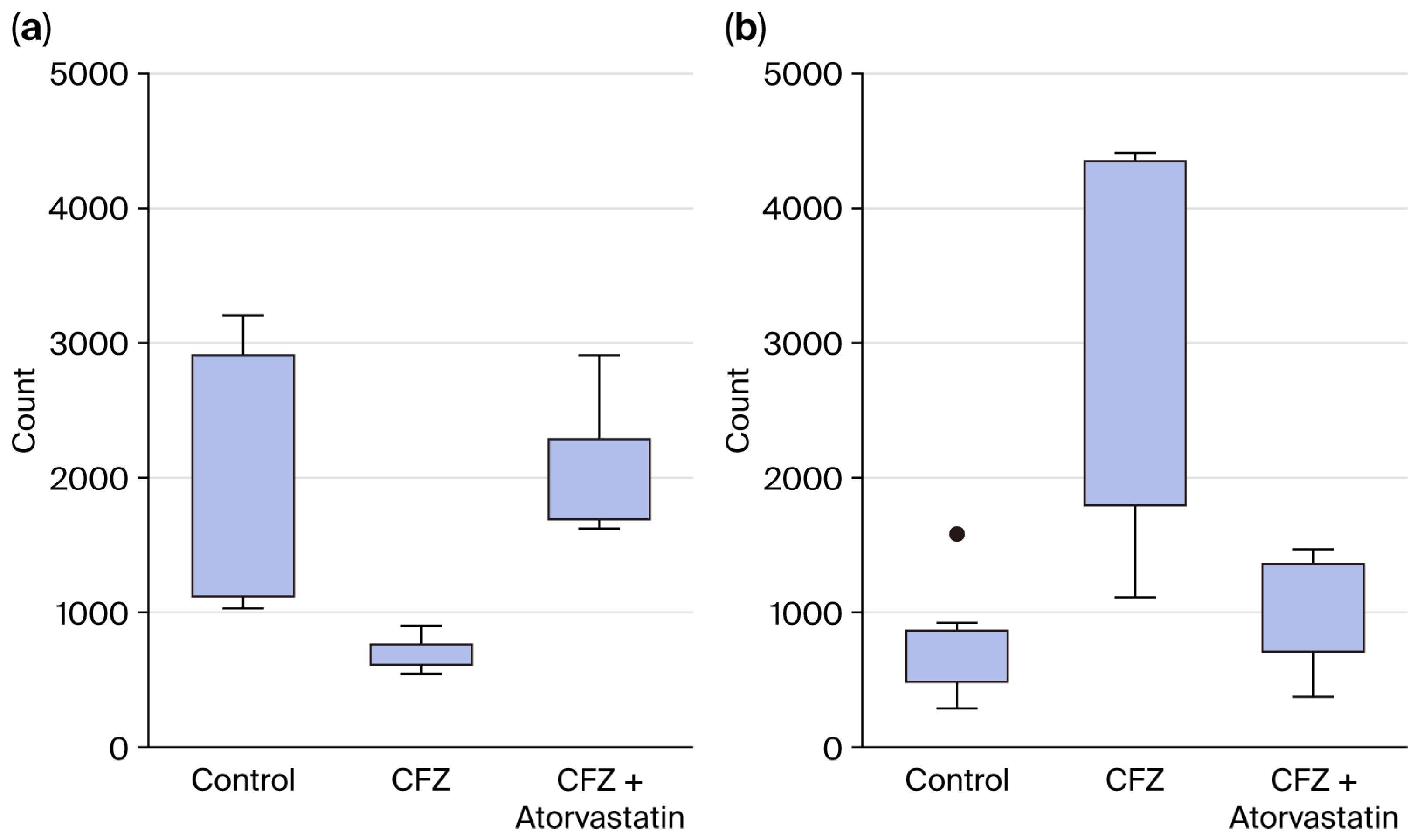

2.2. Establishing the Optimal Carfilzomib Dose for hiPSC-CM Experiments

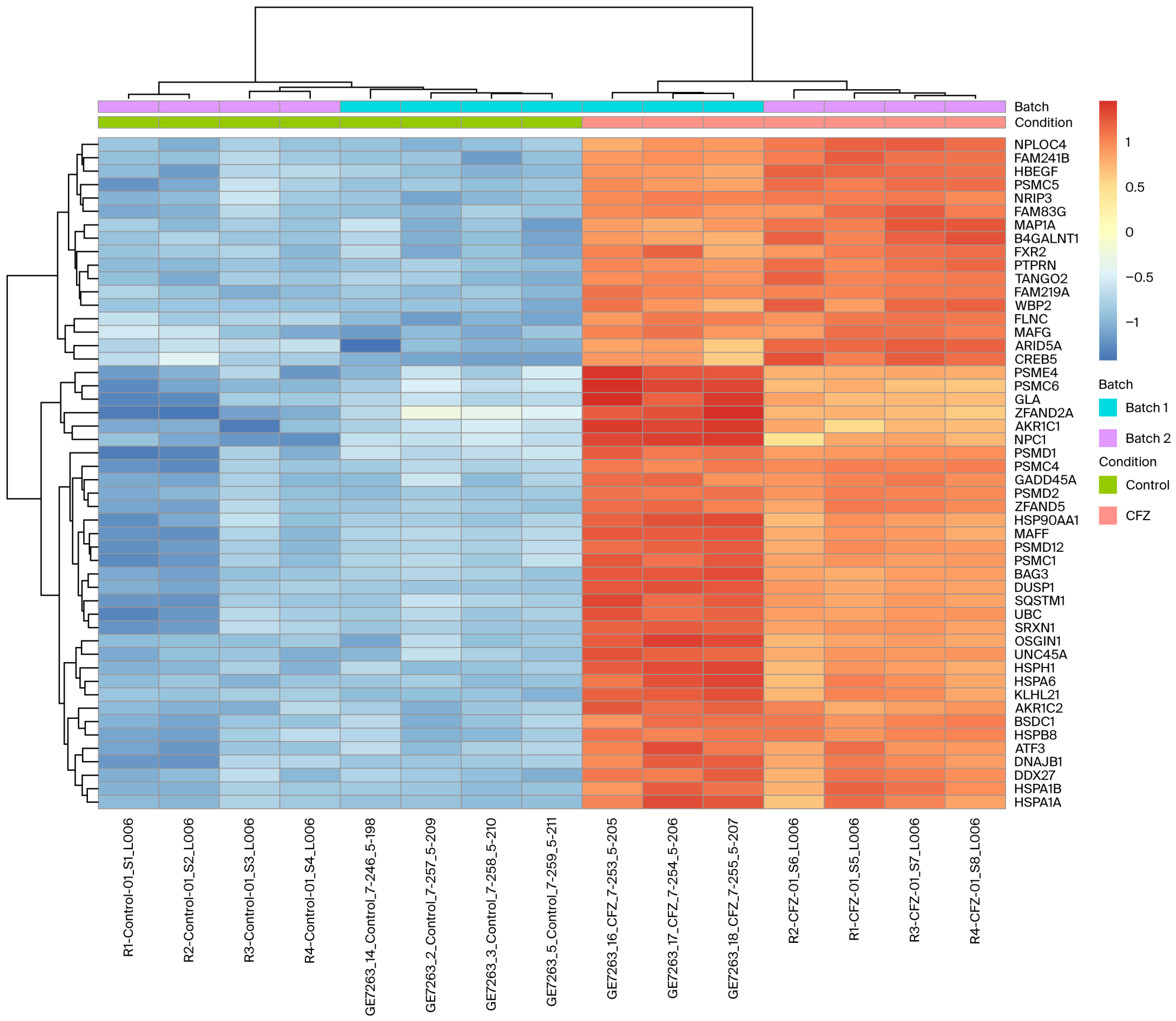

2.3. Differentially Expressed Genes in CFZ vs. Control

2.4. Functional Enrichment of CFZ-Induced Gene Expression Changes

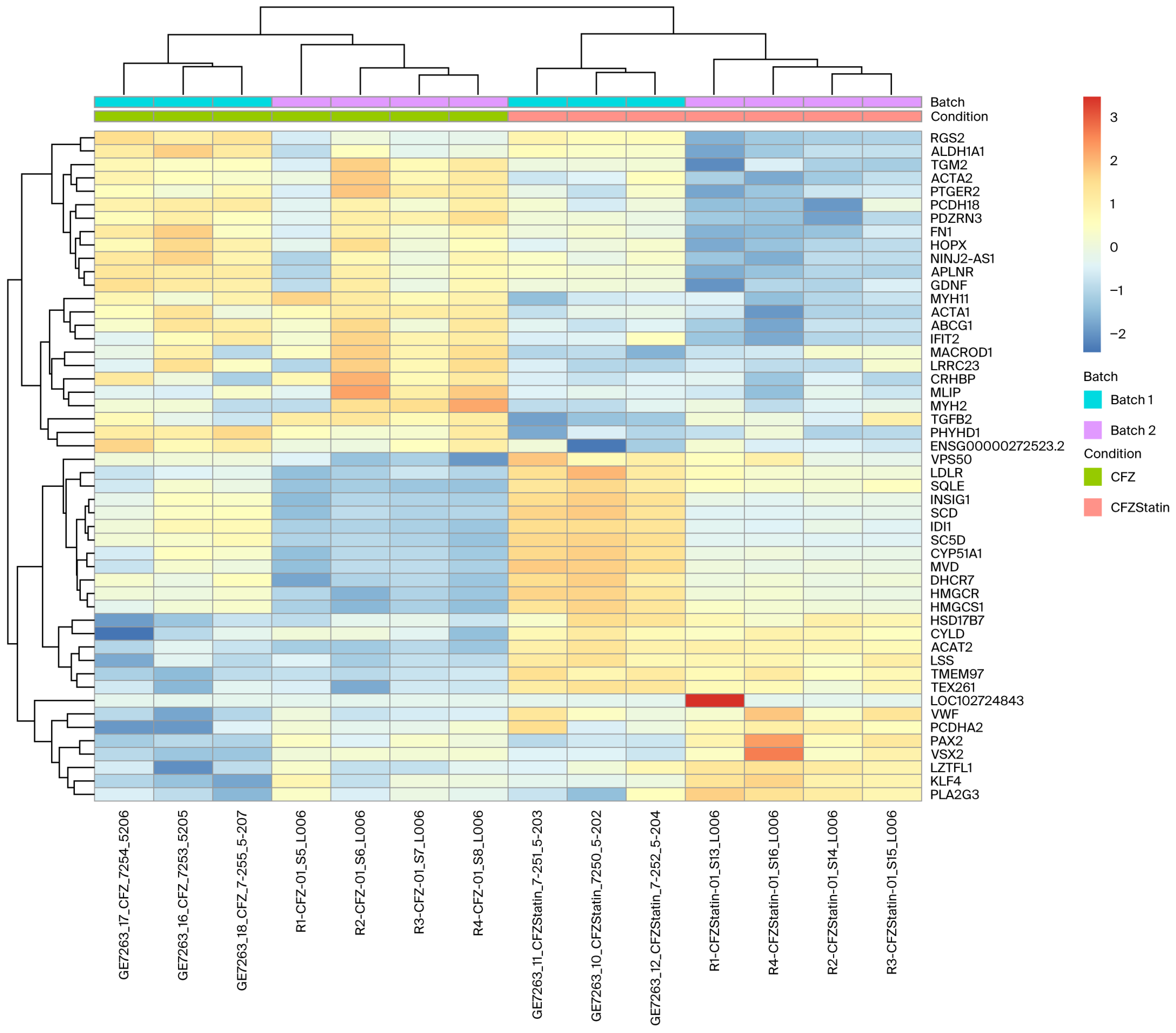

2.5. Transcriptomic Clustering Reveals Metabolic Reprogramming with Limited Sarcomeric Recovery in Cardiomyocytes Treated with CFZ + Atorvastatin

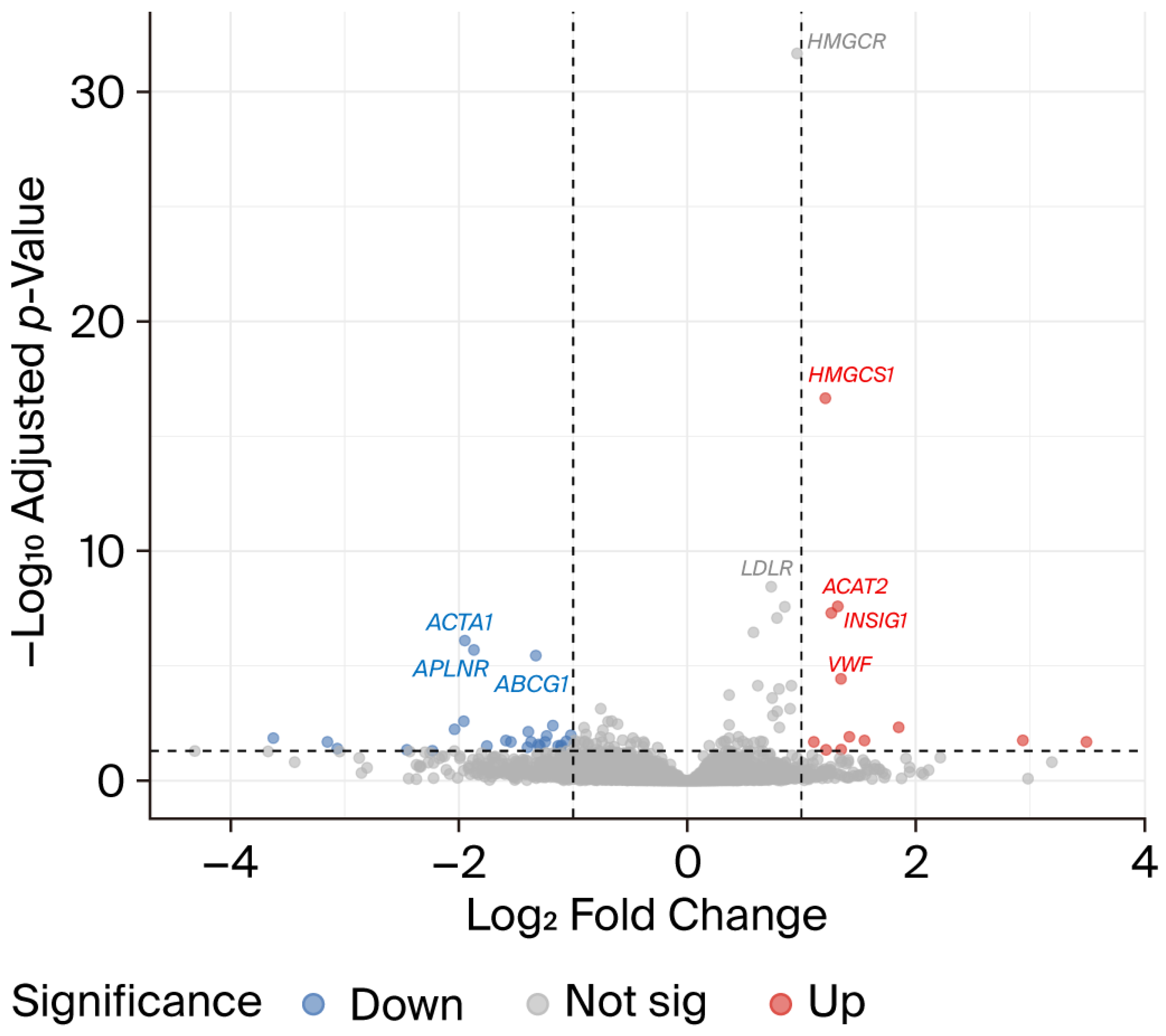

2.6. Atorvastatin Reverses a Subset of CFZ-Induced Transcriptional Alterations

2.7. Validation of RNA-Seq Findings by qPCR

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocyte Differentiation

4.2. Drug Preparation and Treatment

4.3. Quantitative Reverse Transcription–Polymerase Chain Reaction

4.4. RNA Library and RNA Sequencing

4.5. RNA-Seq Analysis and Differential Expression Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CFZ | Carfilzomib |

| CVAE | Cardiovascular adverse event |

| hiPSC-CMs | Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| MM | Multiple myeloma |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, S.V. Multiple myeloma: 2024 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am. J. Hematol. 2024, 99, 1802–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waxman, A.J.; Clasen, S.; Hwang, W.T.; Garfall, A.; Vogl, D.T.; Carver, J.; O’Quinn, R.; Cohen, A.D.; Stadtmauer, E.A.; Ky, B.; et al. Carfilzomib-Associated Cardiovascular Adverse Events: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, e174519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgiopoulos, G.; Makris, N.; Laina, A.; Theodorakakou, F.; Briasoulis, A.; Trougakos, I.P.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Kastritis, E.; Stamatelopoulos, K. Cardiovascular Toxicity of Proteasome Inhibitors: Underlying Mechanisms and Management Strategies. JACC Cardio Oncol. 2023, 5, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoukis, A.; Ntalianis, A.; Repasos, E.; Kastritis, E.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Paraskevaidis, I. Cardio-oncology: A Focus on Cardiotoxicity. Eur. Cardiol. 2018, 13, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, M.L.; Niu, J.; Zhang, N.; Giordano, S.H.; Chavez-MacGregor, M. Cardiotoxicity and Cardiac Monitoring Among Chemotherapy-Treated Breast Cancer Patients. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2018, 11, 1084–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istvan, E.S.; Deisenhofer, J. Structural mechanism for statin inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase. Science 2001, 292, 1160–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, C.P.; Braunwald, E.; McCabe, C.H.; Rader, D.J.; Rouleau, J.L.; Belder, R.; Joyal, S.V.; Hill, K.A.; Pfeffer, M.A.; Skene, A.M.; et al. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 1495–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, F.M.; Pfeffer, M.A.; Moye, L.A.; Rouleau, J.L.; Rutherford, J.D.; Cole, T.G.; Brown, L.; Warnica, J.W.; Arnold, J.M.; Wun, C.C.; et al. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. Cholesterol and Recurrent Events Trial investigators. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 335, 1001–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Danielson, E.; Fonseca, F.A.; Genest, J.; Gotto, A.M.; Kastelein, J.J.; Koenig, W.; Libby, P.; Lorenzatti, A.J.; MacFadyen, J.G.; et al. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 2195–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinlay, S.; Schwartz, G.G.; Olsson, A.G.; Rifai, N.; Leslie, S.J.; Sasiela, W.J.; Szarek, M.; Libby, P.; Ganz, P.; Myocardial Ischemia Reduction with Aggressive Cholesterol Lowering (MIRACL) Study Investigators. High-dose atorvastatin enhances the decline in inflammatory markers in patients with acute coronary syndromes in the MIRACL study. Circulation 2003, 108, 1560–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassmann, S.; Laufs, U.; Bäumer, A.T.; Müller, K.; Ahlbory, K.; Linz, W.; Itter, G.; Rösen, R.; Böhm, M.; Nickenig, G. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors improve endothelial dysfunction in normocholesterolemic hypertension via reduced production of reactive oxygen species. Hypertension 2001, 37, 1450–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oesterle, A.; Laufs, U.; Liao, J.K. Pleiotropic Effects of Statins on the Cardiovascular System. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufs, U.; Fata, V.L.; Liao, J.K. Inhibition of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl (HMG)-CoA reductase blocks hypoxia-mediated down-regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 31725–31729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehnavi, S.; Kiani, A.; Sadeghi, M.; Biregani, A.F.; Banach, M.; Atkin, S.L.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. Targeting AMPK by Statins: A Potential Therapeutic Approach. Drugs 2021, 81, 923–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, Z.; Kale, A.; Turgut, M.; Demircan, S.; Durna, K.; Demir, S.; Meriç, M.; Ağaç, M.T. Efficiency of atorvastatin in the protection of anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 58, 988–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neilan, T.G.; Quinaglia, T.; Onoue, T.; Mahmood, S.S.; Drobni, Z.D.; Gilman, H.K.; Smith, A.; Heemelaar, J.C.; Brahmbhatt, P.; Ho, J.S.; et al. Atorvastatin for Anthracycline-Associated Cardiac Dysfunction: The STOP-CA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2023, 330, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundley, W.G.; D’Agostino, R.; Crotts, T.; Craver, K.; Hackney, M.H.; Jordan, J.H.; Ky, B.; Wagner, L.I.; Herrington, D.M.; Yeboah, J.; et al. Statins and Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction Following Doxorubicin Treatment. NEJM Evid. 2022, 1, EVIDoa2200097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efentakis, P.; Varela, A.; Lamprou, S.; Papanagnou, E.-D.; Chatzistefanou, M.; Christodoulou, A.; Davos, C.H.; Gavriatopoulou, M.; Trougakos, I.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; et al. Implications and hidden toxicity of cardiometabolic syndrome and early-stage heart failure in carfilzomib-induced cardiotoxicity. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 181, 2964–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burridge, P.W.; Holmström, A.; Wu, J.C. Chemically Defined Culture and Cardiomyocyte Differentiation of Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Curr. Protoc. Human. Genet. 2015, 87, 21.3.1–21.3.15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Tanabe, K.; Ohnuki, M.; Narita, M.; Ichisaka, T.; Tomoda, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Adult Human Fibroblasts by Defined Factors. Cell 2007, 131, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burridge, P.W.; Li, Y.F.; Matsa, E.; Wu, H.; Ong, S.G.; Sharma, A.; Holmström, A.; Chang, A.C.; Coronado, M.J.; Ebert, A.D.; et al. Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes recapitulate the predilection of breast cancer patients to doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitani, T.; Ong, S.G.; Lam, C.K.; Rhee, J.W.; Zhang, J.Z.; Oikonomopoulos, A.; Ma, N.; Tian, L.; Lee, J.; Telli, M.L.; et al. Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Model of Trastuzumab-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction in Patients With Breast Cancer. Circulation 2019, 139, 2451–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Burridge, P.W.; McKeithan, W.L.; Serrano, R.; Shukla, P.; Sayed, N.; Churko, J.M.; Kitani, T.; Wu, H.; Holmström, A.; et al. High-throughput screening of tyrosine kinase inhibitor cardiotoxicity with human induced pluripotent stem cells. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaaf2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forghani, P.; Rashid, A.; Sun, F.; Liu, R.; Li, D.; Lee, M.R.; Hwang, H.; Maxwell, J.T.; Mandawat, A.; Wu, R.; et al. Carfilzomib Treatment Causes Molecular and Functional Alterations of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e022247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, C.; Dikic, I. Cellular quality control by the ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy. Science 2019, 366, 818–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaweera, S.P.E.; Wanigasinghe Kanakanamge, S.P.; Rajalingam, D.; Silva, G.N. Carfilzomib: A Promising Proteasome Inhibitor for the Treatment of Relapsed and Refractory Multiple Myeloma. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 740796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, A.J. The role of carfilzomib in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Ther. Adv. Hematol. 2021, 12, 20406207211019612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, M.S.; Townley-Tilson, W.H.; Kang, E.Y.; Homeister, J.W.; Patterson, C. Sent to destroy: The ubiquitin proteasome system regulates cell signaling and protein quality control in cardiovascular development and disease. Circ. Res. 2010, 106, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haertle, L.; Buenache, N.; Cuesta Hernández, H.N.; Simicek, M.; Snaurova, R.; Rapado, I.; Martinez, N.; López-Muñoz, N.; Sánchez-Pina, J.M.; Munawar, U.; et al. Genetic Alterations in Members of the Proteasome 26S Subunit, AAA-ATPase (PSMC) Gene Family in the Light of Proteasome Inhibitor Resistance in Multiple Myeloma. Cancers 2023, 15, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.V.; Mills, J.; Lapierre, L.R. Selective Autophagy Receptor p62/SQSTM1, a Pivotal Player in Stress and Aging. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 793328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedesco, B.; Vendredy, L.; Timmerman, V.; Poletti, A. The chaperone-assisted selective autophagy complex dynamics and dysfunctions. Autophagy 2023, 19, 1619–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Bogomolovas, J.; Wu, T.; Zhang, W.; Liu, C.; Veevers, J.; Stroud, M.J.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, X.; Mu, Y.; et al. Loss-of-function mutations in co-chaperone BAG3 destabilize small HSPs and cause cardiomyopathy. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 3189–3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knezevic, T.; Myers, V.D.; Gordon, J.; Tilley, D.G.; Sharp, T.E.; Wang, J.; Khalili, K.; Cheung, J.Y.; Feldman, A.M. BAG3: A new player in the heart failure paradigm. Heart Fail. Rev. 2015, 20, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakda, S.; Davies, R.H.; Hingorani, A.D.; Paliwal, N. A systematic review of GWAS on CMR imaging traits: Genetic insights into cardiovascular structure, function, and diseases. eBioMedicine 2025, 121, 105992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, S.; Nathan, S.; Kar, B.; Gregoric, I.D.; Li, Y.-P. The Role of Extracellular Heat Shock Proteins in Cardiovascular Diseases. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, N.; Li, D.; Rieder, M.J.; Siegfried, J.D.; Rampersaud, E.; Züchner, S.; Mangos, S.; Gonzalez-Quintana, J.; Wang, L.; McGee, S.; et al. Genome-wide studies of copy number variation and exome sequencing identify rare variants in BAG3 as a cause of dilated cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 88, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez, F.; Cuenca, S.; Bilińska, Z.; Toro, R.; Villard, E.; Barriales-Villa, R.; Ochoa, J.P.; Asselbergs, F.; Sammani, A.; Franaszczyk, M.; et al. Dilated Cardiomyopathy Due to BLC2-Associated Athanogene 3 (BAG3) Mutations. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 2471–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franaszczyk, M.; Bilinska, Z.T.; Sobieszczańska-Małek, M.; Michalak, E.; Sleszycka, J.; Sioma, A.; Małek, Ł.; Kaczmarska, D.; Walczak, E.; Włodarski, P.; et al. The BAG3 gene variants in Polish patients with dilated cardiomyopathy: Four novel mutations and a genotype-phenotype correlation. J. Transl. Med. 2014, 12, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Genga, M.F.; Cuenca, S.; Dal Ferro, M.; Zorio, E.; Salgado-Aranda, R.; Climent, V.; Padrón-Barthe, L.; Duro-Aguado, I.; Jiménez-Jáimez, J.; Hidalgo-Olivares, V.M.; et al. Truncating FLNC Mutations Are Associated With High-Risk Dilated and Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathies. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 68, 2440–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodehl, A.; Ferrier, R.A.; Hamilton, S.J.; Greenway, S.C.; Brundler, M.A.; Yu, W.; Gibson, W.T.; McKinnon, M.L.; McGillivray, B.; Alvarez, N.; et al. Mutations in FLNC are Associated with Familial Restrictive Cardiomyopathy. Hum. Mutat. 2016, 37, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Kumar, P.; Chauhan, L.; Dwivedi, A.; Ramamurthy, H.R. Novel combination of FLNC (c.5707G>A; p. Glu1903Lys) and BAG3 (c.610G>A; p.Gly204Arg) genetic variant expressing restrictive cardiomyopathy phenotype in an adolescent girl. J. Genet. 2022, 101, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberwallner, B.; Brodarac, A.; Anić, P.; Šarić, T.; Wassilew, K.; Neef, K.; Choi, Y.-H.; Stamm, C. Human cardiac extracellular matrix supports myocardial lineage commitment of pluripotent stem cells. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2015, 47, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danhof, S.; Schreder, M.; Rasche, L.; Strifler, S.; Einsele, H.; Knop, S. ‘Real-life’ experience of preapproval carfilzomib-based therapy in myeloma—analysis of cardiac toxicity and predisposing factors. Eur. J. Haematol. 2016, 97, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, S.R.; Williams, A.J. Patterns of interaction between anthraquinone drugs and the calcium-release channel from cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Circ. Res. 1990, 67, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.-F.; Su, W.-C.; Su, C.-C.; Chung, M.-W.; Chang, J.; Li, Y.-Y.; Kao, Y.-J.; Chen, W.-P.; Daniels, M.J. High-Throughput Optical Controlling and Recording Calcium Signal in iPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes for Toxicity Testing and Phenotypic Drug Screening. J. Vis. Exp. 2022, 181, e63175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannuzzi, A.T.; Arslan, S.; Yilmaz, A.M.; Sari, G.; Beklen, H.; Méndez, L.; Fedorova, M.; Arga, K.Y.; Karademir Yilmaz, B.; Alpertunga, B. Higher proteotoxic stress rather than mitochondrial damage is involved in higher neurotoxicity of bortezomib compared to carfilzomib. Redox Biol. 2020, 32, 101502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannuzzi, A.T.; Korkmaz, N.S.; Gunaydin Akyildiz, A.; Arslan Eseryel, S.; Karademir Yilmaz, B.; Alpertunga, B. Molecular Cardiotoxic Effects of Proteasome Inhibitors Carfilzomib and Ixazomib and Their Combination with Dexamethasone Involve Mitochondrial Dysregulation. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2023, 23, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, C.; Trézéguet, V.; Le Saux, A.; Roux, P.; Schwimmer, C.; Dianoux, A.C.; Noel, F.; Lauquin, G.J.M.; Brandolin, G.; Vignais, P.V. The mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier: Structural, physiological and pathological aspects. Biochimie 1998, 80, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, L.; Jia, K.; Chen, C.; Li, Z.; Zhao, J.; Hu, J.; Zhang, H.; Fan, Q.; Huang, C.; Xie, H.; et al. DYRK1B-STAT3 Drives Cardiac Hypertrophy and Heart Failure by Impairing Mitochondrial Bioenergetics. Circulation 2022, 145, 829–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Dalt, L.; Cabodevilla, A.G.; Goldberg, I.J.; Norata, G.D. Cardiac lipid metabolism, mitochondrial function, and heart failure. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 119, 1905–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinton, A.; Claypool, S.M.; Neikirk, K.; Senoo, N.; Wanjalla, C.N.; Kirabo, A.; Williams, C.R. Mitochondrial Structure and Function in Human Heart Failure. Circ. Res. 2024, 135, 372–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zheng, A.; Xu, X.; Shi, Z.; Yang, M.; Sun, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Xiao, Q.; et al. Nrf3-Mediated Mitochondrial Superoxide Promotes Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis and Impairs Cardiac Functions by Suppressing Pitx2. Circulation 2025, 151, 1024–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deavall, D.G.; Martin, E.A.; Horner, J.M.; Roberts, R. Drug-Induced Oxidative Stress and Toxicity. J. Toxicol. 2012, 2012, 645460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angsutararux, P.; Luanpitpong, S.; Issaragrisil, S. Chemotherapy-Induced Cardiotoxicity: Overview of the Roles of Oxidative Stress. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015, 795602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouchani, E.T.; Pell, V.R.; Gaude, E.; Aksentijević, D.; Sundier, S.Y.; Robb, E.L.; Logan, A.; Nadtochiy, S.M.; Ord, E.N.J.; Smith, A.C.; et al. Ischaemic accumulation of succinate controls reperfusion injury through mitochondrial ROS. Nature 2014, 515, 431–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, M. Apoptosis-related genes expressed in cardiovascular development and disease: An EST approach. Cardiovasc. Res. 2000, 45, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Luo, Y.; Wen, Y.; Wang, D.; Li, J.; Fan, Z. Semaglutide inhibits ischemia/reperfusion-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis through activating PKG/PKCε/ERK1/2 pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2023, 647, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makin, G.; Hickman, J.A. Apoptosis and cancer chemotherapy. Cell Tissue Res. 2000, 301, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaomura, T.; Tsuboi, N.; Urahama, Y.; Hobo, A.; Sugimoto, K.; Miyoshi, J.U.N.; Matsuguchi, T.; Reiji, K.; Matsuo, S.; Yuzawa, Y. Serine/threonine kinase, Cot/Tpl2, regulates renal cell apoptosis in ischaemia/reperfusion injury. Nephrology 2008, 13, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varet, H.; Brillet-Guéguen, L.; Coppée, J.Y.; Dillies, M.A. SARTools: A DESeq2- and EdgeR-Based R Pipeline for Comprehensive Differential Analysis of RNA-Seq Data. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patro, R.; Duggal, G.; Love, M.I.; Irizarry, R.A.; Kingsford, C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 417–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soneson, C.; Love, M.I.; Robinson, M.D. Differential analyses for RNA-seq: Transcript-level estimates improve gene-level inferences. F1000Research 2016, 4, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginestet, C. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A Stat. Soc. 2011, 174, 245–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durinck, S.; Spellman, P.T.; Birney, E.; Huber, W. Mapping identifiers for the integration of genomic datasets with the R/Bioconductor package biomaRt. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 1184–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.Y.; Tan, C.M.; Kou, Y.; Duan, Q.; Wang, Z.; Meirelles, G.V.; Clark, N.R.; Ma’ayan, A. Enrichr: Interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Gene ID | CFZ vs. Controls | CFZ + Atorvastatin vs. CFZ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log2 Fold Change | padj | Log2 Fold Change | padj | |||

| ACAT2 | acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 2 | ENSG00000120437 | −1.20 | 7.53 × 10−10 | 1.32 | 2.57 × 10−8 |

| ACTA1 | actin alpha 1, skeletal muscle | ENSG00000143632 | 2.31 | 1.68 × 10−13 | −1.95 | 7.89 × 10−7 |

| PAX2 | paired box 2 | ENSG00000075891 | −4.57 | 5.45 × 10−29 | 1.85 | 0.0047 |

| CRHBP | corticotropin releasing hormone binding protein | ENSG00000145708 | 1.71 | 1.79 × 10−7 | −1.39 | 0.0072 |

| IFIT2 | interferon induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 2 | ENSG00000119922 | 1.20 | 7.15 × 10−5 | −1.23 | 0.011 |

| PLA2G3 | phospholipase A2 group III | ENSG00000100078 | −1.97 | 1.06 × 10−8 | 1.42 | 0.012 |

| VSX2 | visual system homeobox 2 | ENSG00000119614 | −4.69 | 1.23 × 10−10 | 2.94 | 0.017 |

| PCDHA2 | protocadherin alpha 2 | ENSG00000204969 | −1.20 | 0.0036 | 1.55 | 0.018 |

| PTGER2 | prostaglandin E receptor 2 (EP2) | ENSG00000125384 | 1.02 | 0.0148 | −1.59 | 0.018 |

| DERL3 | derlin 3 | ENSG00000099958 | −2.82 | 3.01 × 10−25 | 1.11 | 0.020 |

| NDST4 | N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase 4 | ENSG00000138653 | −6.47 | 4.64 × 10−14 | 3.50 | 0.020 |

| TMEM178B | transmembrane protein 178B | ENSG00000261115 | −2.28 | 4.35 × 10−12 | 1.22 | 0.045 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tantawy, M.; Wang, D.; Gbadamosi, M.; Yu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Alomar, M.E.; Shain, K.H.; Baz, R.C.; Bruno, K.A.; Gong, Y. Atorvastatin Protects Against Deleterious Carfilzomib-Induced Transcriptional Changes in Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1358. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031358

Tantawy M, Wang D, Gbadamosi M, Yu F, Zhang Y, Alomar ME, Shain KH, Baz RC, Bruno KA, Gong Y. Atorvastatin Protects Against Deleterious Carfilzomib-Induced Transcriptional Changes in Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(3):1358. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031358

Chicago/Turabian StyleTantawy, Marwa, Danxin Wang, Mohammed Gbadamosi, Fahong Yu, Yanping Zhang, Mohammed E. Alomar, Kenneth H. Shain, Rachid C. Baz, Katelyn A. Bruno, and Yan Gong. 2026. "Atorvastatin Protects Against Deleterious Carfilzomib-Induced Transcriptional Changes in Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 3: 1358. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031358

APA StyleTantawy, M., Wang, D., Gbadamosi, M., Yu, F., Zhang, Y., Alomar, M. E., Shain, K. H., Baz, R. C., Bruno, K. A., & Gong, Y. (2026). Atorvastatin Protects Against Deleterious Carfilzomib-Induced Transcriptional Changes in Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(3), 1358. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031358