Artificial Intelligence in Nephrology—State of the Art on Theoretical Background, Molecular Applications, and Clinical Interpretation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. General Classification

2.1. Machine Learning

2.2. Unsupervised Learning

2.3. Supervised Learning

2.4. Reinforcement Learning

3. Machine Learning Models

3.1. Random Trees

3.2. Variants of Regression

3.3. eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)

3.4. Support Vector Machine

3.5. K-Nearest Neighbors Classifier (kNN)

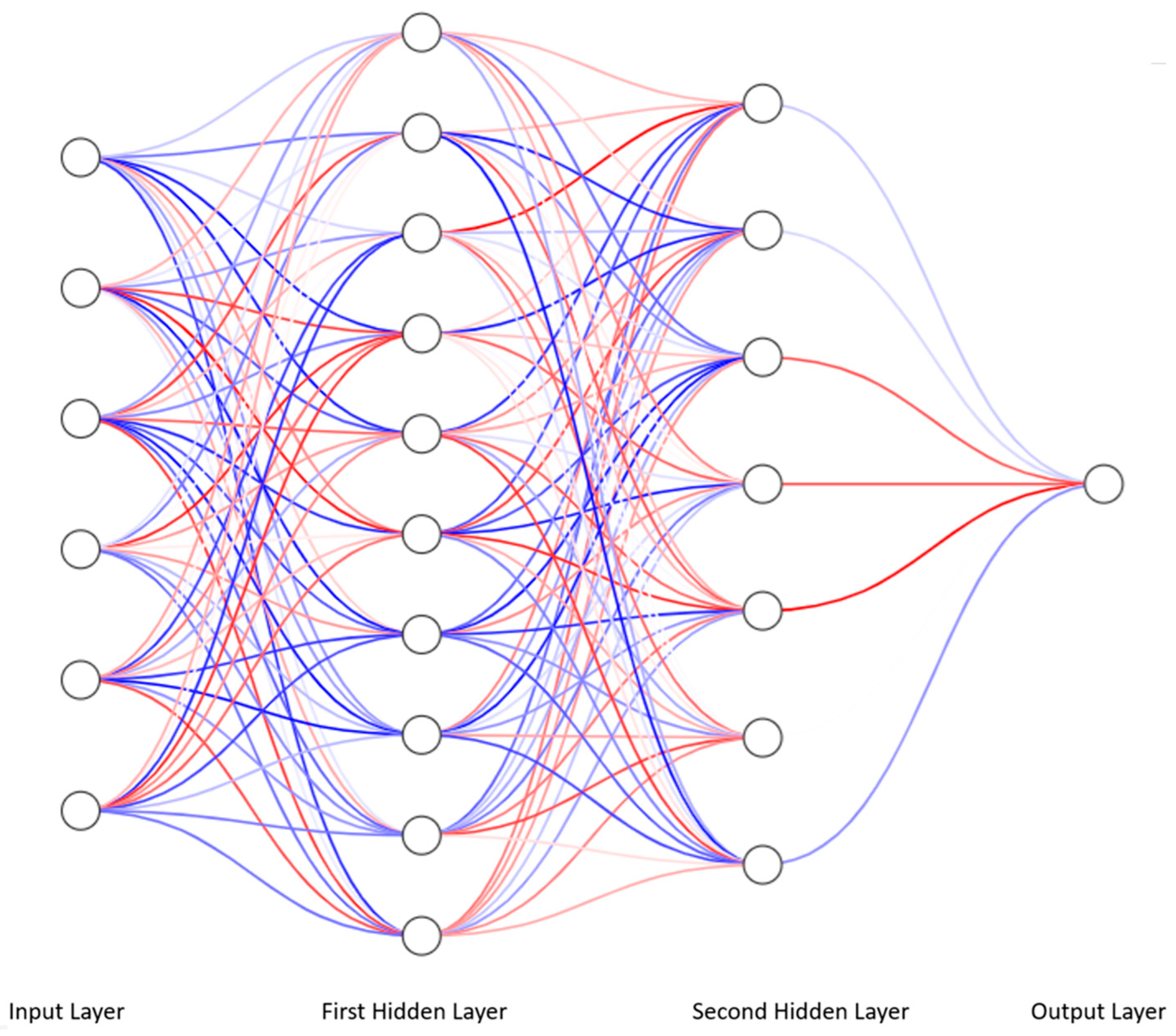

4. Deep Learning and Multilayer Perceptron

4.1. From Linear Regression to Artificial Neural Network

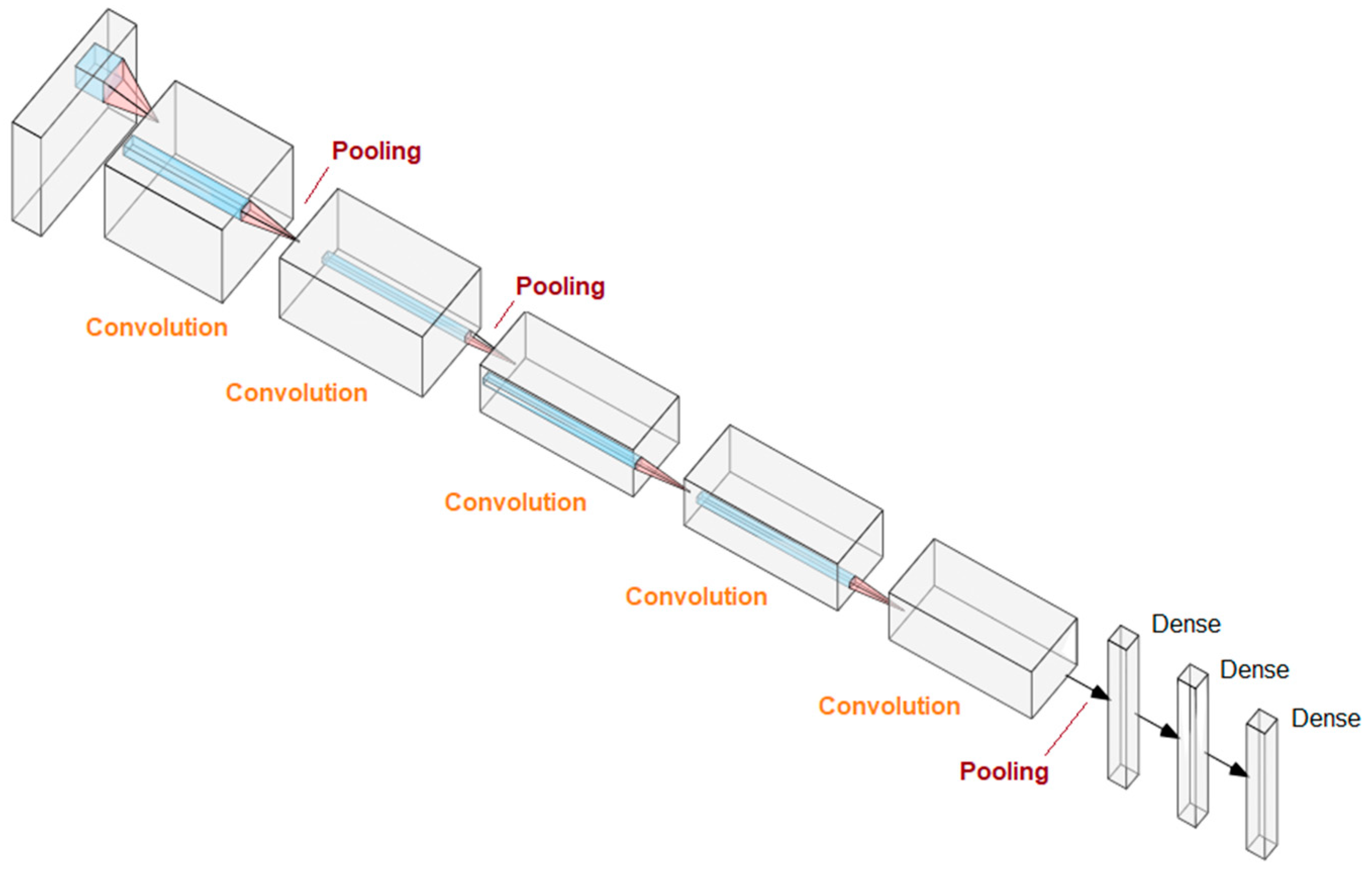

4.2. Deep Learning and Convolutional Neural Networks

5. Comparative Characteristics of Various Methods

6. Limitations

6.1. Missing Data

6.2. Low Number of Patient Records

6.3. Large Number of Variable Parameters

6.4. Selection of the Method

6.5. Dependent Variables and Augmented Data

7. Accuracy Assessment Methods in Machine Learning

8. How to Choose an Appropriate AI Tool? Practical Summary

9. AI-Driven Proteomic Diagnostics—Recent Nephrological Perspective

10. Back to the Future of Nephrology with New Markers

11. Ethical Aspects of AI in Nephrology

12. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A1AT | Alpha-1 antitrypsin |

| ADPKD | Autosomal dominant polycystic kidneys disease |

| AFM | Afamin |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| AKI | Acute kidney injury |

| AlexNet | Alex Krizhevsky Network |

| ANN | Artificial neural network |

| ANXA7 | Annexin A7 |

| APOD | Apolipoprotein D |

| ARID4B | AT-rich interactive domain-containing protein 4B |

| AUC | Area under curve |

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| C9 | Complement component 9 |

| CAD238 | Coronary Artery Disease 238 |

| CARTs | Classification and regression trees |

| ccRCC | Clear cell renal carcinoma |

| CKAP4 | Cytoskeleton-associated protein 4 |

| CKD273 | Chronic kidney disease 273 |

| CNN | Convolutional neural network |

| CP | Ceruloplasmin |

| CTGF | Connective tissue growth factors |

| CXCL10 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 |

| DGF | Delayed graft function |

| DKD | Diabetic kidney disease |

| DoS | Difference of slope |

| eGFR | Estimated Gloimerular Filtration Rate |

| EOMES | Eomesodermin |

| EPTS | Estimated post-transplant survival |

| ESAs | Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents |

| ESKD | End-stage kidney disease |

| ET | Extra trees |

| FN | False negative |

| FP | False positive |

| FPR | False positive rate |

| GIRK-1 | G protein-activated inward rectifier potassium channel 1 |

| GPX3 | Glutathione Peroxidase 3 |

| Hb | Hemoglobin |

| HF2 | Heart failure 2 |

| HR | Heart rate |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| IGFBP2 | Insulin-like Growth Factor-Binding Protein 2 |

| KDPI | Kidney Donor Profile Index |

| KDRI | Kidney Donor Risk Index |

| kNN | K-nearest neighbors classifier |

| LASSO | Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator |

| LGBM | Light Gradient-Boosting Machine |

| LIF | Leukemia inhibitory factor |

| LOOCV | Leave-one-out cross-validation |

| LUTD | Lower urinary tract dysfunction |

| MCC | Matthews correlation coefficient |

| MLP | Multilayer perceptron |

| NGF | Nerve Growth Factor |

| OPN | Osteopontin |

| PLMN | Plasminogen |

| PRMT1 | Protein Arginine Methyltransferase 1 |

| PTX3 | Pentraxin-3 |

| ResNet | Residual Network |

| RFC | Random Forest Classifier |

| RFCs | Random Forest Classifiers |

| RI | Resistive index |

| ROC | Receiver-operator curve |

| sAlb | Serum albumin |

| SHBG | Sex hormone binding globulin |

| STAT1 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| SVM | Support vector machine |

| SVM-RFE | Support vector machine recursive feature elimination |

| SWE | Shear wave elastography |

| TF | Transcription factor |

| TN | True negative |

| TP | True positive |

| TPR | True positive rate |

| UACR | Urinary albumin creatinine ratio |

| UCI | University of California Irvine |

| U-Net | U-shaped architecture Network |

| VPS4A | Vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 4A |

| XGBoost | eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

References

- McCarthy, J.; Minsky, M.L.; Rochester, N.; Shannon, C.E. A Proposal for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence. 1955. Available online: http://www-formal.stanford.edu/jmc/history/dartmouth/dartmouth.html (accessed on 12 January 2026).

- Xie, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Lu, G. Evolution of artificial intelligence in healthcare: A 30-year bibliometric study. Front. Med. 2025, 11, 1505692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statt, N. The AI boom is happening all over the world, and it’s accelerating quickly. The Verge, 12 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X.; Shang, B.; Xie, C.; Xin, J.; Yu, F. Artificial intelligence in the COVID-19 pandemic: Balancing benefits and ethical challenges in China’s response. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reznichenko, A.; Nair, V.; Eddy, S.; Fermin, D.; Tomilo, M.; Slidel, T.; Ju, W.; Henry, I.; Badal, S.S.; Wesley, J.D.; et al. Unbiased kidney-centric molecular categorization of chronic kidney disease as a step towards precision medicine. Kidney Int. 2024, 105, 1263–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schork, A.; Fritsche, A.; Schleicher, E.D.; Peter, A.; Heni, M.; Stefan, N.; von Schwartzenberg, R.J.; Guthoff, M.; Mischak, H.; Siwy, J.; et al. Differential risk assessment in persons at risk of type 2 diabetes using urinary peptidomics. Metabolism 2025, 167, 156174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, N.; Uchino, E.; Kojima, R.; Sakuragi, M.; Hiragi, S.; Minamiguchi, S.; Haga, H.; Yokoi, H.; Yanagita, M.; Okuno, Y. Evaluation of Kidney Histological Images Using Unsupervised Deep Learning. Kidney Int. Rep. 2021, 6, 2445–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongprayoon, C.; Vaitla, P.; Jadlowiec, C.C.; Leeaphorn, N.; Mao, S.A.; Mao, M.A.; Pattharanitima, P.; Bruminhent, J.; Khoury, N.J.; Garovic, V.D.; et al. Use of Machine Learning Consensus Clustering to Identify Distinct Subtypes of Black Kidney Transplant Recipients and Associated Outcomes. JAMA Surg. 2022, 157, e221286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongprayoon, C.; Vaitla, P.; Jadlowiec, C.C.; Mao, S.A.; Mao, M.A.; Acharya, P.C.; Leeaphorn, N.; Kaewput, W.; Pattharanitima, P.; Tangpanithandee, S.; et al. Differences between kidney retransplant recipients as identified by machine learning consensus clustering. Clin. Transplant. 2023, 37, e14943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Lv, G.; Liu, X.; Xiao, Y.; Tan, Y.; Zhu, Y. Machine learning selection of basement membrane-associated genes and development of a predictive model for kidney fibrosis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massy, Z.A.; Lambert, O.; Metzger, M.; Sedki, M.; Chaubet, A.; Breuil, B.; Jaafar, A.; Tack, I.; Nguyen-Khoa, T.; Alves, M.; et al. Machine Learning-Based Urine Peptidome Analysis to Predict and Understand Mechanisms of Progression to Kidney Failure. Kidney Int. Rep. 2022, 8, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deo, R.; Dubin, R.F.; Ren, Y.; Wang, J.; Feldman, H.; Shou, H.; Coresh, J.; Grams, M.E.; Surapaneni, A.L.; Cohen, J.B.; et al. Proteomic Assessment of the Risk of Secondary Cardiovascular Events among Individuals with CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2025, 36, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Feng, T.; Thapa-Chhetry, B.; Cho, B.G.; Shum, T.; Inwald, D.P.; Newth, C.J.L.; Vaidya, V.U. Machine learning model for early prediction of acute kidney injury (AKI) in pediatric critical care. Crit. Care 2021, 25, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Lu, Y.; Li, S.; Guo, F.; Xue, H.; Jiang, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Xie, W.; Zhu, F. Predicting renal function recovery and short-term reversibility among acute kidney injury patients in the ICU: Comparison of machine learning methods and conventional regression. Ren. Fail. 2022, 44, 1326–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ho, K.M.; Hong, Y. Machine learning for the prediction of volume responsiveness in patients with oliguric acute kidney injury in critical care. Crit. Care 2019, 23, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eghbali, N.; Alhanai, T.; Ghassemi, M.M. Patient-Specific Sedation Management via Deep Reinforcement Learning. Front. Digit. Health 2021, 3, 608893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Tian, Y.; Zhou, T.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Chen, J.; Li, J. Optimization of Dry Weight Assessment in Hemodialysis Patients via Reinforcement Learning. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2022, 26, 4880–4891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escandell-Montero, P.; Chermisi, M.; Martínez-Martínez, J.M.; Gómez-Sanchis, J.; Barbieri, C.; Soria-Olivas, E.; Mari, F.; Vila-Francés, J.; Stopper, A.; Gatti, E.; et al. Optimization of anemia treatment in hemodialysis patients via reinforcement learning. Artif. Intell. Med. 2014, 62, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaweda, A.E.; Muezzinoglu, M.K.; Jacobs, A.A.; Aronoff, G.R.; Brier, M.E. Model predictive control with reinforcement learning for drug delivery in renal anemia management. In 2006 International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 5177–5180. [Google Scholar]

- Kha, Q.-H.; Le, V.-H.; Hung, T.N.K.; Nguyen, N.T.K.; Le, N.Q.K. Development and Validation of an Explainable Machine Learning-Based Prediction Model for Drug–Food Interactions from Chemical Structures. Sensors 2023, 23, 3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Ren, H.; Wang, T.; Zhang, R.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Development and internal validation of machine learning algorithms for end-stage renal disease risk prediction model of people with type 2 diabetes mellitus and diabetic kidney disease. Ren. Fail. 2022, 44, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Dong, Z.; Wang, Q.; Pei, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, P.; Feng, Z.; et al. New Diagnostic Model for the Differentiation of Diabetic Nephropathy from Non-Diabetic Nephropathy in Chinese Patients. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 913021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Gong, T.; Lin, Y.; Wang, J.; Sun, L.; Wei, H.; Yang, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Zhao, L.; et al. Urine proteomics identifies biomarkers for diabetic kidney disease at different stages. Clin. Proteom. 2021, 18, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kononikhin, A.S.; Brzhozovskiy, A.G.; Bugrova, A.E.; Chebotareva, N.V.; Zakharova, N.V.; Semenov, S.; Vinogradov, A.; Indeykina, M.I.; Moiseev, S.; Larina, I.M.; et al. Targeted MRM Quantification of Urinary Proteins in Chronic Kidney Disease Caused by Glomerulopathies. Molecules 2023, 28, 3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, N.; Friedman, J.H.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. Regularization Paths for Cox’s Proportional Hazards Model via Coordinate Descent. J. Stat. Softw. 2011, 39, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunleye, A.; Wang, Q.G. XGBoost Model for Chronic Kidney Disease Diagnosis. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2020, 17, 2131–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.H.; Chiang, J.H.; Tsai, C.C.; Chiu, P.F. Predicting hyperkalemia in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease using the XGBoost model. BMC Nephrol. 2023, 24, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, J.; Liu, S.; Li, M.; Hu, K.; Li, K. Predicting mortality of patients with acute kidney injury in the ICU using XGBoost model. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Xia, E.; Qin, Y.; Liang, S.; Xu, F.; Liang, D.; Zeng, C.; Liu, Z. Prediction and Risk Stratification of Kidney Outcomes in IgA Nephropathy. Am. J. Kidney Dis. Off. J. Natl. Kidney Found. 2019, 74, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.M.; Hu, J.; Xu, Y.; Abraham, A.G.; Xiao, R.; Coresh, J.; Rebholz, C.; Chen, J.; Rhee, E.P.; Feldman, H.I.; et al. Using Machine Learning to Identify Metabolomic Signatures of Pediatric Chronic Kidney Disease Etiology. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. JASN 2022, 33, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallion, S.; McLarnon, T.; Cooper, E.; English, A.R.; Watterson, S.; Chemaly, M.E.; McGeough, C.; Eakin, A.; Ahmed, T.; Gardiner, P.; et al. Senescence Biomarkers CKAP4 and PTX3 Stratify Severe Kidney Disease Patients. Cells 2024, 13, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazyrin, Y.E.; Veprintsev, D.V.; Ler, I.A.; Rossovskaya, M.L.; Varygina, S.A.; Glizer, S.L.; Zamay, T.N.; Petrova, M.M.; Minic, Z.; Berezovski, M.V.; et al. Proteomics-Based Machine Learning Approach as an Alternative to Conventional Biomarkers for Differential Diagnosis of Chronic Kidney Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tisch, A.; Madapoosi, S.; Blough, S.; Rosa, J.; Eddy, S.; Mariani, L.; Naik, A.; Limonte, C.; McCown, P.; Menon, R.; et al. Identification of kidney cell types in scRNA-seq and snRNA-seq data using machine learning algorithms. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, S.; Li, S.; Huang, X.; Liu, J.; Hou, X.; Zhao, Y.; Niu, D.; Wang, Y.; Tan, W.; Wu, J. Machine learning for the prediction of acute kidney injury in patients with sepsis. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, T.; Maupong, T.; Mpoeleng, D.; Semong, T.; Mphago, B.; Tabona, O. A survey on missing data in machine learning. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahboob, T.; Ijaz, A.; Shahzad, A.; Kalsoom, M. Handling Missing Values in Chronic Kidney Disease Datasets Using KNN, K-Means and K-Medoids Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2018 12th International Conference on Open Source Systems and Technologies (ICOSST), Lahore, Pakistan, 19–21 December 2018; pp. 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermsen, M.; de Bel, T.; den Boer, M.; Steenbergen, E.J.; Kers, J.; Florquin, S.; Roelofs, J.J.T.H.; Stegall, M.D.; Alexander, M.P.; Smith, B.H.; et al. Deep Learning-Based Histopathologic Assessment of Kidney Tissue. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. JASN 2019, 30, 1968–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kers, J.; Bülow, R.D.; Klinkhammer, B.M.; Breimer, G.E.; Fontana, F.; Abiola, A.A.; Hofstraat, R.; Corthals, G.L.; Peters-Sengers, H.; Djudjaj, S.; et al. Deep learning-based classification of kidney transplant pathology: A retrospective, multicentre, proof-of-concept study. Lancet Digit. Health 2022, 4, e18–e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouteldja, N.; Klinkhammer, B.M.; Bülow, R.D.; Droste, P.; Otten, S.W.; Freifrau von Stillfried, S.; Moellmann, J.; Sheehan, S.M.; Korstanje, R.; Menzel, S.; et al. Deep Learning-Based Segmentation and Quantification in Experimental Kidney Histopathology. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. JASN 2021, 32, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, S.; Yao, Y.; Bi, C.; Liu, C.; Sun, G.; Su, H.; Li, X.; Li, X.; et al. Deep learning-based multi-omics study reveals the polymolecular phenotypic of diabetic kidney disease. Clin. Transl. Med. 2023, 13, e1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Ying, T.C.; Chen, J.; Wu, C.; Li, L.; Chen, H.; Xiao, T.; Huang, Y.; Chen, X.; Jiang, J.; et al. Using elastography-based multilayer perceptron model to evaluate renal fibrosis in chronic kidney disease. Ren. Fail. 2023, 45, 2202755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, T.W.; Kim, M.S.; Park, J.W.; Kwon, K.K.; Kim, K.H. Multilayer Perceptron-Based Real-Time Intradialytic Hypotension Prediction Using Patient Baseline Information and Heart-Rate Variation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, J.; Pedraza, A.; Lopez, S.; Steiner, G.; Gonzalez, L.; Laurinavicius, A.; Bueno, G. Glomerulus Classification and Detection Based on Convolutional Neural Networks. J. Imaging 2018, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; Proceedings, Part III 18; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Chen, H.; Li, J.; Wang, L. Boundary Attention U-Net for Kidney and Kidney Tumor Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Glasgow, UK, 11–15 July 2022; pp. 1540–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rombolotti, M.; Sangalli, F.; Cerullo, D.; Remuzzi, A.; Lanzarone, E. Automatic cyst and kidney segmentation in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: Comparison of U-Net based methods. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 146, 105431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhm, K.H.; Jung, S.W.; Choi, M.H.; Shin, H.K.; Yoo, J.I.; Oh, S.W.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, H.G.; Lee, Y.J.; Youn, S.Y.; et al. Deep learning for end-to-end kidney cancer diagnosis on multi-phase abdominal computed tomography. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 2021, 5, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Delgado, M.; Cernadas, E.; Barro, S. Do We Need Hundreds of Classifers to Solve Real World Classifcation Problems? J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2014, 15, 3133–3181. [Google Scholar]

- Konieczny, A.; Stojanowski, J.; Rydzyńska, K.; Kusztal, M.; Krajewska, M. Artificial Intelligence—A Tool for Risk Assessment of Delayed-Graft Function in Kidney Transplant. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, D.; Tan, X.; Tang, X.; Zhang, F.; Xia, M.; Chen, G.; He, L.; Zhou, L.; et al. Prediction of ESRD in IgA Nephropathy Patients from an Asian Cohort: A Random Forest Model. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2018, 43, 1852–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konieczny, A.; Stojanowski, J.; Krajewska, M.; Kusztal, M. Machine Learning in Prediction of IgA Nephropathy Outcome: A Comparative Approach. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beghdadi, N.; Kitano, Y.; Golse, N.; Vibert, E.; Cunha, A.S.; Azoulay, D.; Cherqui, D.; Adam, R.; Allard, M.-A. Features Importance in Acute Kidney Injury After Liver Transplant: Which Predictors Are Relevant? Exp. Clin. Transplant. 2023, 21, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musiał, K.; Stojanowski, J.; Miśkiewicz-Bujna, J.; Kałwak, K.; Ussowicz, M. KIM-1, IL-18, and NGAL, in the Machine Learning Prediction of Kidney Injury among Children Undergoing Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation—A Pilot Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawalec, A.; Stojanowski, J.; Mazurkiewicz, P.; Choma, A.; Gaik, M.; Pluta, M.; Szymański, M.; Bruciak, A.; Gołębiowski, T.; Musiał, K. Systemic Immune Inflammation Index as a Key Predictor of Dialysis in Pediatric Chronic Kidney Disease with the Use of Random Forest Classifier. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharjee, A.; Larkman, J.; Xu, Y.; Cardoso, V.R.; Gkoutos, G.V. A random forest based biomarker discovery and power analysis framework for diagnostics research. BMC Med. Genom. 2020, 13, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, D.; Wang, W.J.; Chen, C.C. Evaluation of a decided sample size in machine learning applications. BMC Bioinform. 2023, 24, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailly, A.; Blanc, C.; Francis, É.; Guillotin, T.; Jamal, F.; Wakim, B.; Roy, P. Effects of dataset size and interactions on the prediction performance of logistic regression and deep learning models. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2022, 213, 106504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zantvoort, K.; Nacke, B.; Görlich, D.; Hornstein, S.; Jacobi, C.; Funk, B. Estimation of minimal data sets sizes for machine learning predictions in digital mental health interventions. NPJ Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammoudeh, Z.; Lowd, D. Training data influence analysis and estimation: A survey. Mach. Learn. 2024, 113, 2351–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gütter, J.; Kruspe, A.; Zhu, X.X.; Niebling, J. Impact of Training Set Size on the Ability of Deep Neural Networks to Deal with Omission Noise. Front. Remote Sens. 2022, 3, 932431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ishwaran, H. Random forests for genomic data analysis. Genomics 2012, 99, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, D.; Cabrera, J. Enriched Random Forest for High Dimensional Genomic Data. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2022, 19, 2817–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramezan, C.A.; Warner, T.A.; Maxwell, A.E.; Price, B.S. Effects of Training Set Size on Supervised Machine-Learning Land-Cover Classification of Large-Area High-Resolution Remotely Sensed Data. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattab, G.; Arnold, M.; Strenger, L.; Allan, M.; Arsentjeva, D.; Gold, O.; Simpfendörfer, T.; Maier-Hein, L.; Speidel, S. Kidney edge detection in laparoscopic image data for computer-assisted surgery: Kidney edge detection. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2020, 15, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, C.W. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Anesthesiology. Anesthesiology 2019, 131, 1346–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chicco, D.; Jurman, G. The advantages of the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) over F1 score and accuracy in binary classification evaluation. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powers, D.M. Evaluation: From precision, recall and F-measure to ROC, informedness, markedness and correlation. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.16061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanowski, J.; Konieczny, A.; Lis, Ł.; Frosztęga, W.; Brzozowska, P.; Ciszewska, A.; Rydzyńska, K.; Sroka, M.; Krakowska, K.; Gołębiowski, T.; et al. The Artificial Neural Network as a Diagnostic Tool of the Risk of Clostridioides difficile Infection among Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, M.B.; Marks-Hultström, M.; Åberg, M.; Lipcsey, M.; Frithiof, R.; Larsson, A.O. Mapping Interactions Between Cytokines, Chemokines, Growth Factors, and Conventional Biomarkers in COVID-19 ICU-Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkash, E.A.; Wilson, A.M.; Jentzen, J.M. Ultrastructural evidence for direct renal infection with SARS-CoV-2. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 31, 1683–1687, Erratum in J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 31, 2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Yang, M.; Wan, C.; Yi, L.-X.; Tang, F.; Zhu, H.-Y.; Yi, F.; Yang, H.-C.; Fogo, A.B.; Nie, X. Renal histopathological analysis of 26 postmortem findings of patients with COVID-19 in China. Kidney Int. 2020, 98, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sur, S.; Khatun, M.; Steele, R.; Isbell, T.S.; Ray, R.; Ray, R.B. Exosomes from COVID-19 patients carry tenascin-C and fibrinogen-β in triggering inflammatory signals in cells of distant organ. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzanowska, K.; Batko, K.; Niezabitowska, K.; Woźnica, K.; Grodzicki, T.; Małecki, M.; Bociąga-Jasik, M.; Rajzer, M.; Sładek, K.; Wizner, B.; et al. Predicting acute kidney injury onset with a random forest algorithm using electronic medical records of COVID-19 patients: The CRACoV-AKI model. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2024, 134, 16697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljohani, M.A. Exosomes in Clinical Laboratory: From Biomarker Discovery to Diagnostic Implementation. Medicina 2025, 61, 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalani, A.; Chaturvedi, S.; Chaturvedi, P. Wilms’ tumor 1 in urinary exosomes as a non-invasive biomarker for diabetic nephropathy. Clin. Chim. Acta 2026, 579, 120599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, W.-C.; Chen, C.-S.; Chang, Y.-P.; Wu, C.-S.; Yang, H.-C.; Chang, J.-F. CCN2/CTGF-Driven Myocardial Fibrosis and NT-proBNP Synergy as Predictors of Mortality in Maintenance Hemodialysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagin, F.H.; Inceoglu, F.; Colak, C.; Alkhalifa, A.K.; Alzakari, S.A.; Aghaei, M. Machine Learning-Integrated Explainable Artificial Intelligence Approach for Predicting Steroid Resistance in Pediatric Nephrotic Syndrome: A Metabolomic Biomarker Discovery Study. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delrue, C.; Speeckaert, M.M. Transcriptomic Signatures in IgA Nephropathy: From Renal Tissue to Precision Risk Stratification. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, P.-H.; Huang, S.M.; Tsai, Y.-C.; Wang, Y.-T.; Chew, F.Y. Biomarkers in Contrast-Induced Nephropathy: Advances in Early Detection, Risk Assessment, and Prevention Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Nicolás, M.Á.; González-Guerrero, C.; Goicoechea, M.; Boscá, L.; Valiño-Rivas, L.; Lázaro, A. Biomarkers in Contrast-Induced Acute Kidney Injury: Towards A New Perspective. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, S.; Ishima, T.; Iwami, D.; Nagai, R.; Aizawa, K. Trans-Omic Analysis Identifies the ‘PRMT1–STAT3–Integrin αVβ6 Axis’ as a Novel Therapeutic Target in Tacrolimus-Induced Chronic Nephrotoxicity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Yu, S.; Yang, D.; Yu, T.; Liu, Y.; Du, W. Integrated Multi-Omics Analysis Unveils Distinct Molecular Subtypes and a Robust Immune–Metabolic Prognostic Model in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, B.; Du, H.; Tong, H.H.Y.; Wang, X.; Li, K. Enhancing Local Functional Structure Features to Improve Drug–Target Interaction Prediction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manan, A.; Baek, E.; Ilyas, S.; Lee, D. Digital Alchemy: The Rise of Machine and Deep Learning in Small-Molecule Drug Discovery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messa, L.; Testa, C.; Carelli, S.; Rey, F.; Jacchetti, E.; Cereda, C.; Raimondi, M.T.; Ceri, S.; Pinoli, P. Non-Negative Matrix Tri-Factorization for Representation Learning in Multi-Omics Datasets with Applications to Drug Repurposing and Selection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Miyano, S. DD-CC-II: Data Driven Cell–Cell Interaction Inference and Its Application to COVID-19. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepoittevin, M.; Remaury, Q.B.; Lévêque, N.; Thille, A.W.; Brunet, T.; Salaun, K.; Catroux, M.; Pellerin, L.; Hauet, T.; Thuillier, R. Advantages of Metabolomics-Based Multivariate Machine Learning to Predict Disease Severity: Example of COVID. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Choi, E.; Shim, Y.; Kwon, J. PriorCCI: Interpretable Deep Learning Framework for Identifying Key Ligand–Receptor Interactions Between Specific Cell Types from Single-Cell Transcriptomes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.-H.; Jhang, J.-F.; Wang, J.-H.; Wu, Y.-H.; Kuo, H.-C. A Decision Tree Model Using Urine Inflammatory and Oxidative Stress Biomarkers for Predicting Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction in Females. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weightman, A.; Clayton, P.; Coghlan, S. Confronting the Ethical Issues with Artificial Intelligence Use in Nephrology. Kidney360 2025. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llerena-Izquierdo, J.; Ayala-Carabajo, R. Ethics of the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Academia and Research: The Most Relevant Approaches, Challenges and Topics. Informatics 2025, 12, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | AI Method | Input Variables | Target Point | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yuan et al. [10] | LASSO logistic regression, RFC, SVM-RFE | Genes ARID4B, EOMES, KCNJ3, LIF and STAT1 | Kidney fibrosis | AUC of 0.923 |

| Kha et al. [20] | RFC, XGBoost, ET, LGBM, MLP | 18 values derived from molecular computational methods | Possible drug–food constituent interactions (DFIs) | Accuracy of 96.75% for XGBoost |

| Massy et al. [11] | Clustering and Regularized Cox Regression | Set of 90 urinary peptides | Kidney failure | AUC of 0.83 |

| Reznichenko et al. [5] | Self-Organizing Maps unsupervised ANN ML algorithm | A set of upregulated and downregulated genes associated with faster progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD) | CKD reclasification | AUC of 0.825 |

| McCallion et al. [31] | SVM | CKAP4, PTX3, IGFBP2, OPN | Senescence in AKI and CKD vs. comorbidities | AUC of 0.98 for CKAP4 |

| Schork et al. [6] | LASSO regression | Among 112 peptides CKD273, HF2, and CAD238 were statistically significant | Clustering into groups at risk of developing diabetes and diabetes complications | AUC of 0.868 with 95% CI 0.755–0.981 |

| Deo et al. [12] | Elastic Net Regression | Set of 16 proteins | Secondary cardiovascular events | AUC of 0.77–0.80 |

| Fan et al. [23] | Logistic regression | Sets of 2, 3 and 4 proteins: ALB + AFM, ANXA7 + APOD + C9, SERPINA5 + VPS4A + CP + TF | DKD vs. uncomplicated diabetic patients and DKD3 vs. DKD4, progression to DKD | AUC of 0.928, AUC of 0.949, AUC of 0.952, respectively |

| Kononikhin et al. [24] | Logistic regression, k-NN, SVM | Set of GPX3, PLMN, and A1AT or SHBG | Mild vs. severe glomerulopathies | AUC of 0.99 |

| Glazyrin et al. [32] | KNeighbors (kNN), logistic regression, support vector machine (SVM), and decision tree | Set of biochemistry parameters, clusters | Various groups of chronic kidney disease of renal and postrenal or systemic etiology (prerenal) | Accuracy of 96.3% for glomerulonephritris and 96.4% diabetic nephropaty |

| Method | Application | Requirements | Advantages | Disadvantages | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artificial intelligence/ Machine learning | Support Vector Machine | Classification and regression of tabular data [27,30,34] | Complete data | Simplicity | Insufficient in more complex tasks, possible low performance on large sets | ||

| Random Forest Classifier | Classification [34] and regression of tabular data Feature importation [50,53] | Complete data, partially insensitive to missing data | Simplicity, insensitivity to irrelevant variables, partial resistance to outliers | May be insufficient in more complex tasks | |||

| XGBoost | Classification and regression of tabular data [26,27,28,29,34] | Complete data | Simplicity | ||||

| kNN | Data imputation [35] regression, classification [32,34] | Empty cells for imputation | Simplicity | Possible low performance on large sets with many variables. Sensitive to missing and outlier data. Except for data imputation, rather limited use | |||

| Artificial Neural Network | Multilayer Perceptron | Classification and regression of tabular data [34,41,42] | Necessary data scaling, standardization, improved performance | Can learn non-linear relationships Can learn up to date through additional data | Hyperparameter tuning required Sensitive to scaling of input data | ||

| Deep learning | Convolutional Neural Network | Classification [38,43,48], deviation detection [43], segmentation [45,46,47,48] | Mainly imaging, histopathological, radiological data, etc. | Complexity enabling deep image analysis. Possibility to upload large amounts of data. Application of a once trained network in various approaches | Complexity, risk of overfitting to too few input data due to the multitude of parameters inside the model. Requirement of a sufficiently large number of class representatives | ||

| U-Net [45,46,47] | |||||||

| ResNet18 [38] ResNet50 [38] ResNet101 [38,48] | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Stojanowski, J.; Gołębiowski, T.; Musiał, K. Artificial Intelligence in Nephrology—State of the Art on Theoretical Background, Molecular Applications, and Clinical Interpretation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031285

Stojanowski J, Gołębiowski T, Musiał K. Artificial Intelligence in Nephrology—State of the Art on Theoretical Background, Molecular Applications, and Clinical Interpretation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(3):1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031285

Chicago/Turabian StyleStojanowski, Jakub, Tomasz Gołębiowski, and Kinga Musiał. 2026. "Artificial Intelligence in Nephrology—State of the Art on Theoretical Background, Molecular Applications, and Clinical Interpretation" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 3: 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031285

APA StyleStojanowski, J., Gołębiowski, T., & Musiał, K. (2026). Artificial Intelligence in Nephrology—State of the Art on Theoretical Background, Molecular Applications, and Clinical Interpretation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(3), 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031285