bFGF Oligomeric Stability Drives Functional Performance in Human Pluripotent Stem Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Supplier-Dependent Physicochemical Heterogeneity in bFGF and TGF-β3

2.1.1. bFGF Oligomeric State and Sequence Analysis

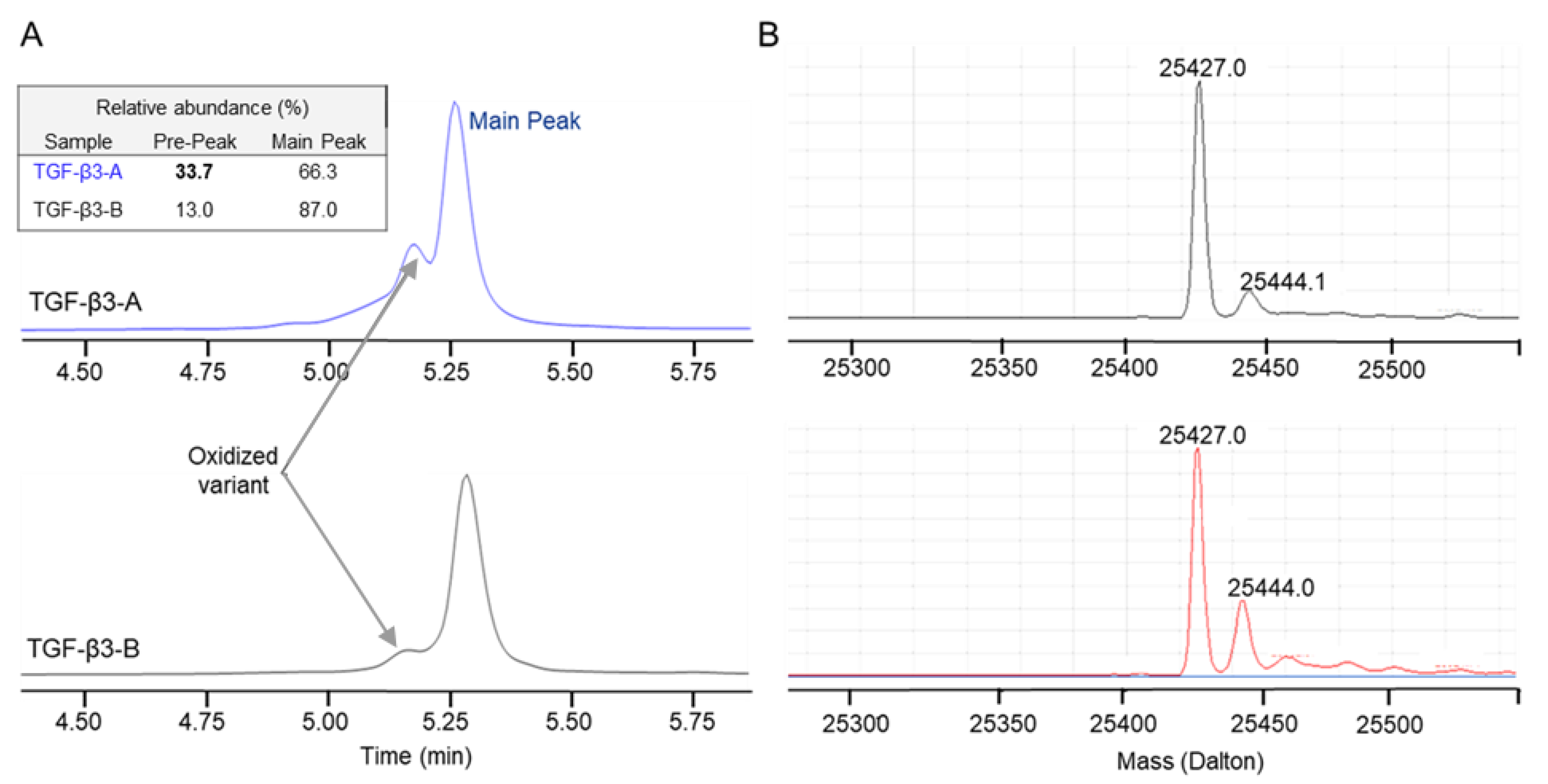

2.1.2. TGF-β3 Purity and Post-Translational Modification Analysis

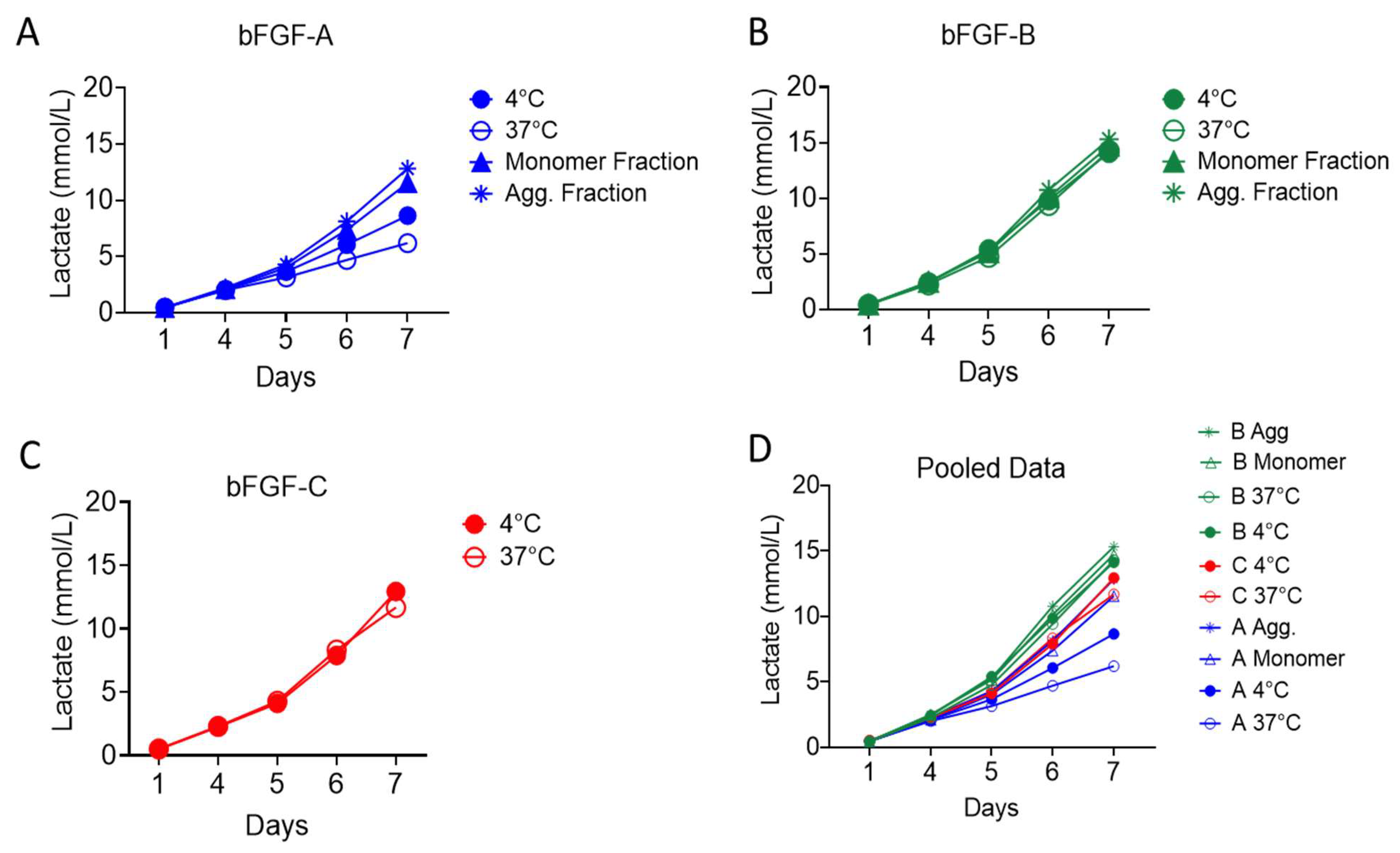

2.2. Functional Characterization of Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor Materials in Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Expansion

2.2.1. Impact of Thermal Pretreatment on Functional Activity

2.2.2. Functional Contribution of Aggregation State

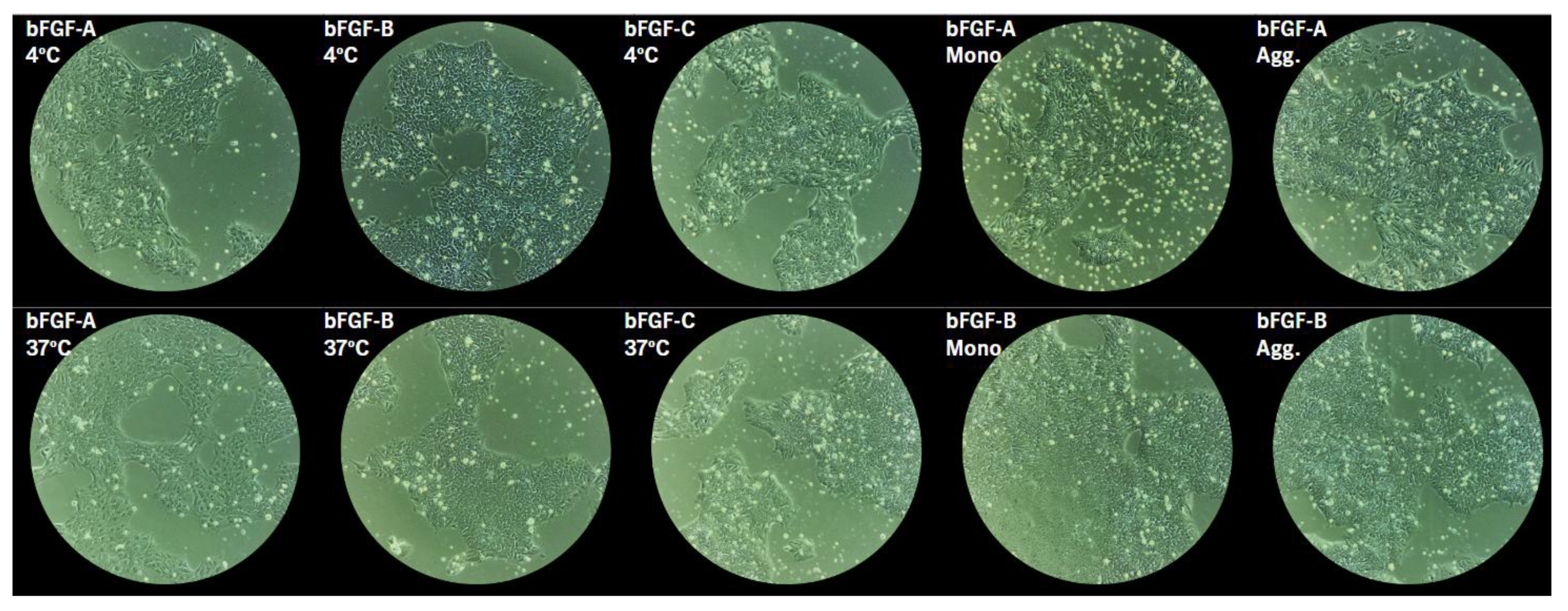

2.2.3. Morphological Assessment

2.2.4. TGF-β3 Assessment

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. bFGF and TGF-β3 Materials

4.2. Cell Media and Reagents

4.3. Physicochemical Characterization

4.3.1. SEC-UV Analysis

4.3.2. 2D (SEC × RP) LC/MS Analysis

4.3.3. RP LC/MS Intact Mass Analysis

4.3.4. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

4.4. Functionality Assessment

4.4.1. Lactate Measurement

4.4.2. Morphology Assessment

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, K.G.; Mallon, B.S.; McKay, R.D.G.; Robey, P.G. Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Culture: Considerations for Maintenance, Expansion, and Therapeutics. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 14, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, H.; Matsumoto, T.; Nakagawa, M. Culturing Human Pluripotent Stem Cells for Regenerative Medicine. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2023, 23, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa-Diaz, L.G.; Ross, A.M.; Lahann, J.; Krebsbach, P.H. The Evolution of Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Culture: From Feeder Cells to Synthetic Coatings. Stem Cells 2013, 31, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, T.E.; Bergendahl, V.; Levenstein, M.E.; Yu, J.; Probasco, M.D.; Thomson, J.A. Feeder-Independent Culture of Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Nat. Methods 2006, 3, 637–646, Erratum in Nat. Methods 2006, 3, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Gulbranson, D.R.; Hou, Z.; Bolin, J.M.; Ruotti, V.; Probasco, M.D.; Smuga-Otto, K.; Howden, S.E.; Diol, N.R.; Propson, N.E.; et al. Chemically Defined Conditions for Human iPSC Derivation and Culture. Nat. Methods 2011, 8, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, D.; Levine, A.J.; Besser, D.; Hemmati-Brivanlou, A. TGFβ/Activin/Nodal Signaling Is Necessary for the Maintenance of Pluripotency in Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Dev. Camb. Engl. 2005, 132, 1273–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mossahebi-Mohammadi, M.; Quan, M.; Zhang, J.-S.; Li, X. FGF Signaling Pathway: A Key Regulator of Stem Cell Pluripotency. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oke, A.; Manohar, S.M. Dynamic Roles of Signaling Pathways in Maintaining Pluripotency of Mouse and Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Cell. Reprogramming 2024, 26, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Gulbranson, D.R.; Yu, P.; Hou, Z.; Thomson, J.A. Thermal Stability of Fibroblast Growth Factor Protein Is a Determinant Factor in Regulating Self-Renewal, Differentiation, and Reprogramming in Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Stem Cells 2012, 30, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koledova, Z.; Sumbal, J.; Rabata, A.; de La Bourdonnaye, G.; Chaloupkova, R.; Hrdlickova, B.; Damborsky, J.; Stepankova, V. Fibroblast Growth Factor 2 Protein Stability Provides Decreased Dependence on Heparin for Induction of FGFR Signaling and Alters ERK Signaling Dynamics. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.J.; Jung, Y.-E.; Lee, K.W.; Kaushal, P.; Ko, I.Y.; Shin, S.M.; Ji, S.; Yu, W.; Lee, C.; Lee, W.-K.; et al. Structural and Biochemical Investigation into Stable FGF2 Mutants with Novel Mutation Sites and Hydrophobic Replacements for Surface-Exposed Cysteines. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, H.-H.; Gao, X.; DeKeyser, J.-M.; Fetterman, K.A.; Pinheiro, E.A.; Weddle, C.J.; Fonoudi, H.; Orman, M.V.; Romero-Tejeda, M.; Jouni, M.; et al. Negligible-Cost and Weekend-Free Chemically Defined Human iPSC Culture. Stem Cell Rep. 2020, 14, 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorak, P.; Bednar, D.; Vanacek, P.; Balek, L.; Eiselleova, L.; Stepankova, V.; Sebestova, E.; Kunova Bosakova, M.; Konecna, Z.; Mazurenko, S.; et al. Computer-Assisted Engineering of Hyperstable Fibroblast Growth Factor 2. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2018, 115, 850–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benington, L.; Rajan, G.; Locher, C.; Lim, L.Y. Fibroblast Growth Factor 2-A Review of Stabilisation Approaches for Clinical Applications. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Xie, C.; Cai, Y.; Chen, X.; Hou, Y.; He, L.; Li, J.; Yao, M.; Chen, S.; et al. Peptide Ligands Targeting FGF Receptors Promote Recovery from Dorsal Root Crush Injury via AKT/mTOR Signaling. Theranostics 2021, 11, 10125–10147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Takahashi, K.; Campion, S.L.; Liu, Y.; Gustavsen, G.G.; Peña, L.A.; Zamora, P.O. Synthetic Peptide F2A4-K-NS Mimics Fibroblast Growth Factor-2 in Vitro and Is Angiogenic in Vivo. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2006, 17, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimicking the Bioactivity of Fibroblast Growth Factor-2 Using Supramolecular Nanoribbons | ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering. Available online: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsbiomaterials.7b00347 (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Jendryczko, K.; Chudzian, J.; Skinder, N.; Opaliński, Ł.; Rzeszótko, J.; Wiedlocha, A.; Otlewski, J.; Szlachcic, A. FGF2-Derived PeptibodyF2-MMAE Conjugate for Targeted Delivery of Cytotoxic Drugs into Cancer Cells Overexpressing FGFR1. Cancers 2020, 12, 2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakui, T.; Matsumoto, T.; Matsubara, K.; Kawasaki, T.; Yamaguchi, H.; Akutsu, H. Method for Evaluation of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Quality Using Image Analysis Based on the Biological Morphology of Cells. J. Med. Imaging 2017, 4, 044003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakao, S.; Kitada, M.; Kuroda, Y.; Ogura, F.; Murakami, T.; Niwa, A.; Dezawa, M. Morphologic and Gene Expression Criteria for Identifying Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Ruiz, F.J.; Introna, C.; Bombau, G.; Galofre, M.; Canals, J.M. Standardization of Cell Culture Conditions and Routine Genomic Screening under a Quality Management System Leads to Reduced Genomic Instability in hPSCs. Cells 2022, 11, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beers, J.; Gulbranson, D.R.; George, N.; Siniscalchi, L.I.; Jones, J.; Thomson, J.A.; Chen, G. Passaging and Colony Expansion of Human Pluripotent Stem Cells by Enzyme-Free Dissociation in Chemically Defined Culture Conditions. Nat. Protoc. 2012, 7, 2029–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakhore, S.; Nayer, B.; Hasegawa, K. Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Culture: Current Status, Challenges, and Advancement. Stem Cells Int. 2018, 2018, 7396905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchtova, M.; Chaloupkova, R.; Zakrzewska, M.; Vesela, I.; Cela, P.; Barathova, J.; Gudernova, I.; Zajickova, R.; Trantirek, L.; Martin, J.; et al. Instability Restricts Signaling of Multiple Fibroblast Growth Factors. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 2445–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlessinger, J.; Plotnikov, A.N.; Ibrahimi, O.A.; Eliseenkova, A.V.; Yeh, B.K.; Yayon, A.; Linhardt, R.J.; Mohammadi, M. Crystal Structure of a Ternary FGF-FGFR-Heparin Complex Reveals a Dual Role for Heparin in FGFR Binding and Dimerization. Mol. Cell 2000, 6, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Q8, Q9, & Q10 Questions and Answers—Appendix: Q&As from Training Sessions (Q8, Q9, & Q10 Points to Consider). Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/q8-q9-q10-questions-and-answers-appendix-qas-training-sessions-q8-q9-q10-points-consider (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Abraham, J. International Conference On Harmonisation Of Technical Requirements For Registration Of Pharmaceuticals For Human Use. In Handbook of Transnational Economic Governance Regimes; Tietje, C., Brouder, A., Eds.; Brill | Nijhoff: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 1041–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Kim, S.-H.; Decker, C.G.; Wong, D.Y.; Loo, J.A.; Maynard, H.D. A Heparin-Mimicking Polymer Conjugate Stabilizes Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor (bFGF). Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonehara, R.; Kumachi, S.; Kashiwagi, K.; Wakabayashi-Nakao, K.; Motohashi, M.; Murakami, T.; Yanagisawa, T.; Arai, H.; Murakami, A.; Ueno, Y.; et al. A Novel Agonist with Homobivalent Single-Domain Antibodies That Bind the FGF Receptor 1 Domain III Functions as an FGF2 Ligand. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 102804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Lim, K.-M.; Bong, H.; Lee, S.-B.; Jeon, T.-I.; Lee, S.-Y.; Park, H.-S.; Kim, J.-Y.; Song, K.; Kang, G.-H.; et al. The Immobilization of an FGF2-Derived Peptide on Culture Plates Improves the Production and Therapeutic Potential of Extracellular Vesicles from Wharton’s Jelly Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq, M.; Hwang, M.; Khan, A.W.; Batool, M.; Ahmad, B.; Kim, W.; Kim, M.S.; Choi, S. Identification of a Novel Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor-Agonistic Peptide and Its Effect on Diabetic Wound Healing. Life Sci. 2025, 364, 123432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Iannitelli, D.E.; Kim, N.; Ayalew, L.; Wu, Q.; Guo, X.V.; Spitler, K.; Srikanth, M.P.; Camperi, J. bFGF Oligomeric Stability Drives Functional Performance in Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1283. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031283

Iannitelli DE, Kim N, Ayalew L, Wu Q, Guo XV, Spitler K, Srikanth MP, Camperi J. bFGF Oligomeric Stability Drives Functional Performance in Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(3):1283. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031283

Chicago/Turabian StyleIannitelli, Dylan E., Naryeong Kim, Luladey Ayalew, Qiang Wu, Xinzheng Victor Guo, Kyle Spitler, Manasa P. Srikanth, and Julien Camperi. 2026. "bFGF Oligomeric Stability Drives Functional Performance in Human Pluripotent Stem Cells" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 3: 1283. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031283

APA StyleIannitelli, D. E., Kim, N., Ayalew, L., Wu, Q., Guo, X. V., Spitler, K., Srikanth, M. P., & Camperi, J. (2026). bFGF Oligomeric Stability Drives Functional Performance in Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(3), 1283. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031283