Sex Hormones-Mediated Modulation of Immune Checkpoints in Pregnancy and Recurrent Pregnancy Loss

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

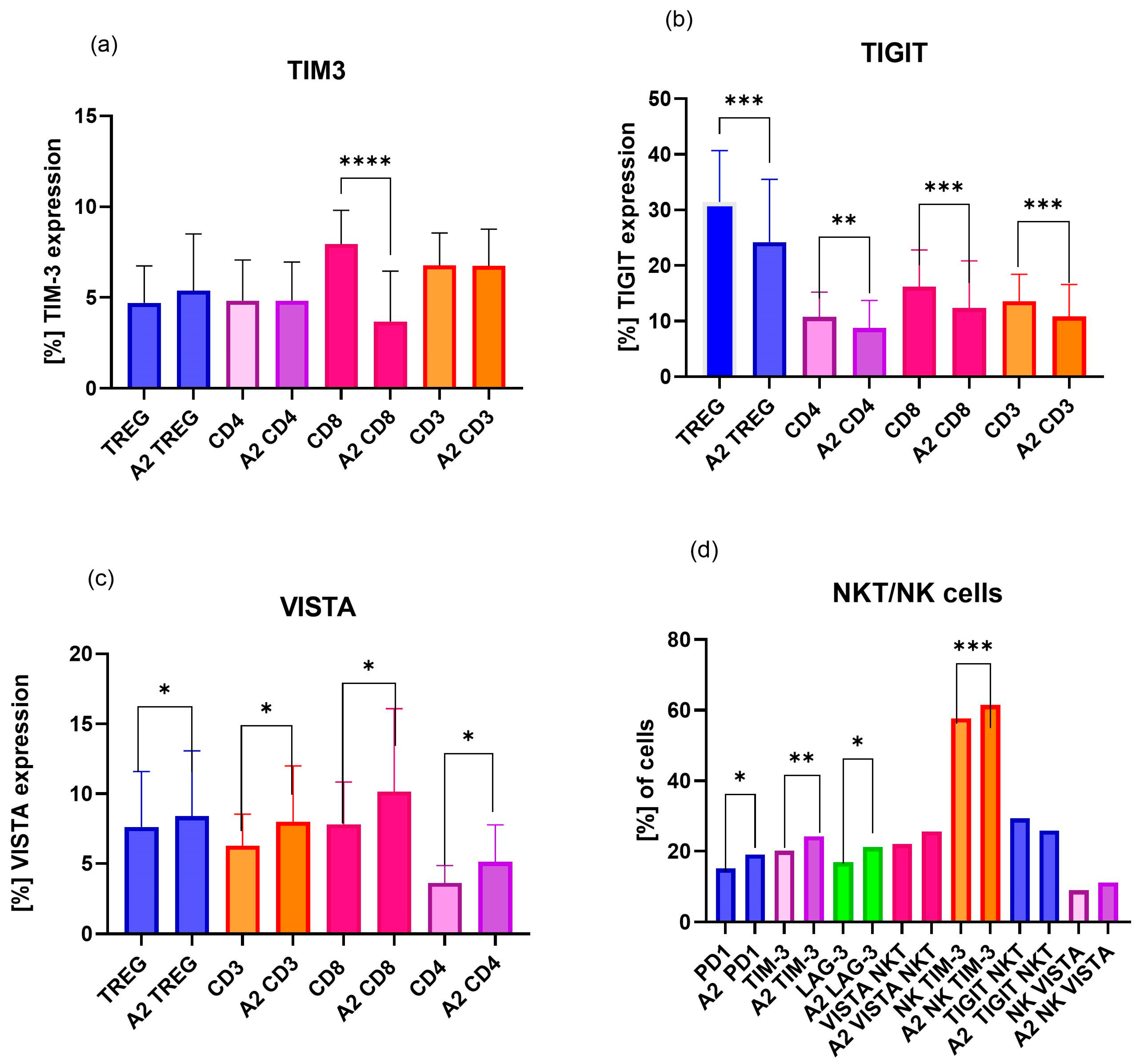

2.1. Analysis of Differences in Expression of ICPs on Immune Cells, Including Treg, CD4, CD8, CD3, NK, and NKT Cells, Between Pregnant Women and uRPL Patients

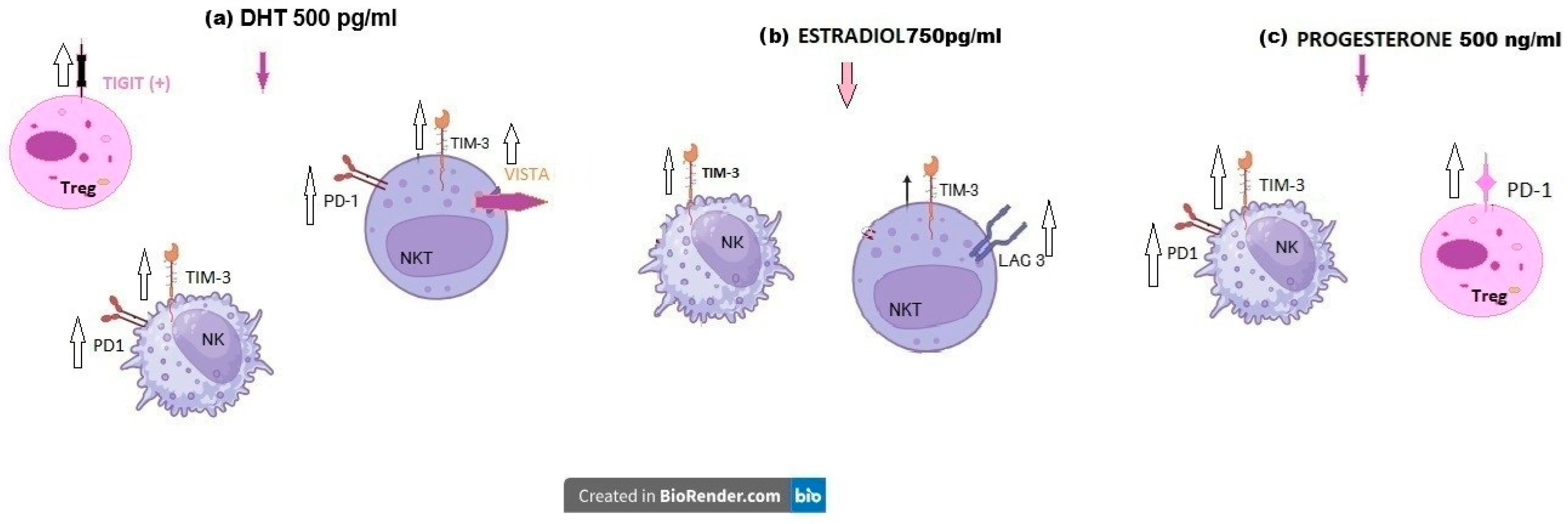

2.2. Analysis of Differences in Expression of ICPs on Pregnant Women’s Immune Cells, Including Treg, CD4, CD8, CD3, NK, and NKT, After SH Stimulation

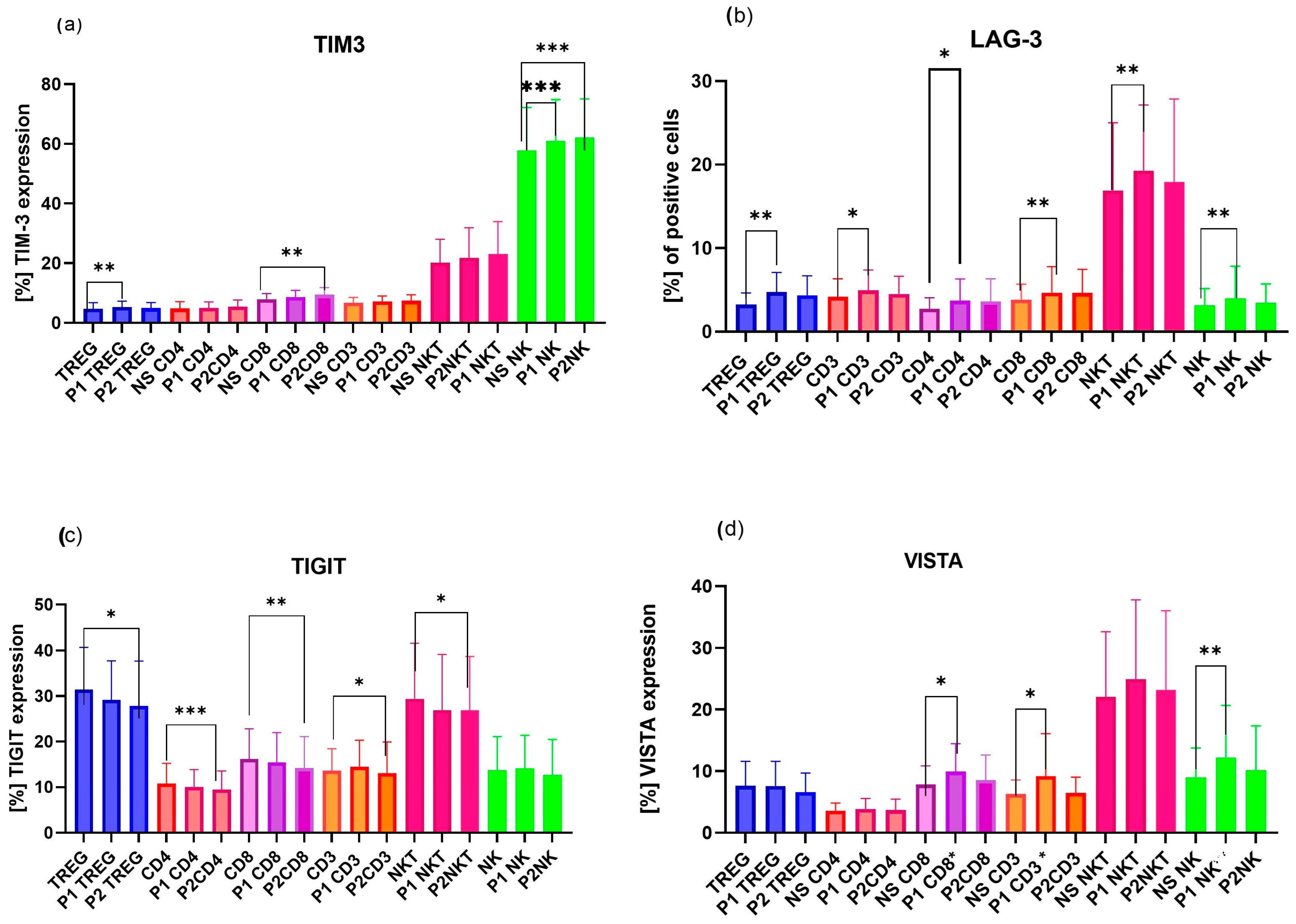

2.3. Analysis of Differences in Expression of ICPs on uRPL Women’s Immune Cells, Including Treg, CD4, CD8, CD3, NK, and NKT

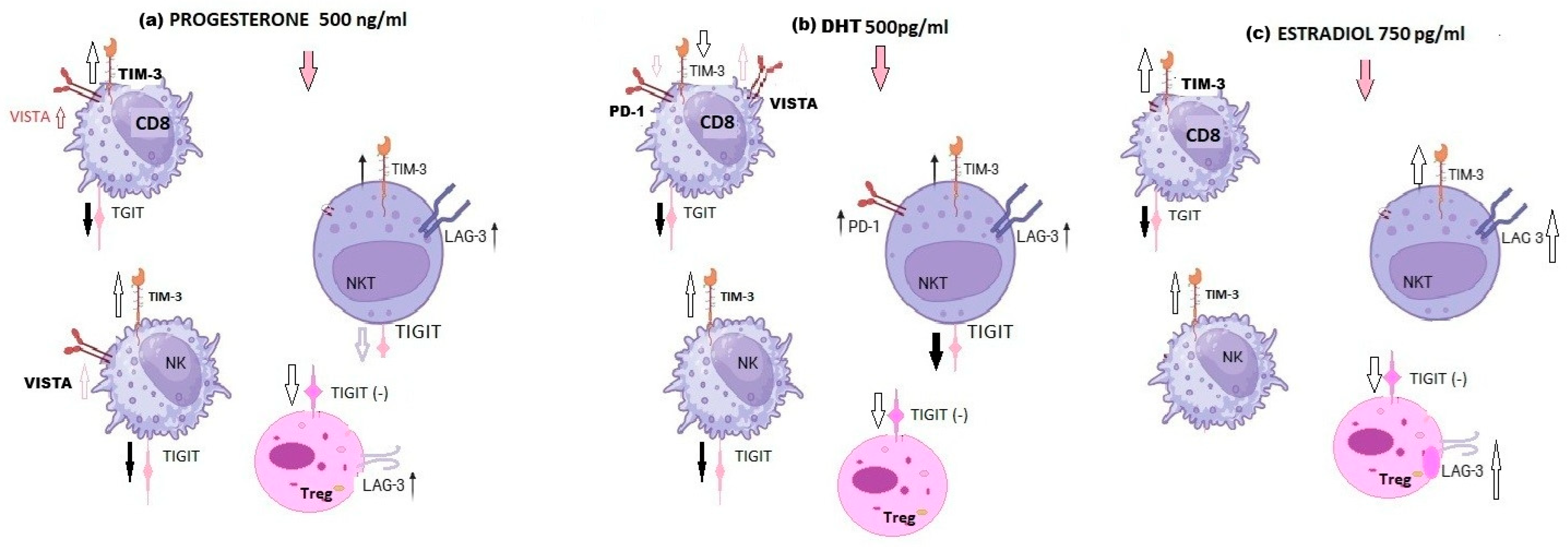

2.3.1. Influence of Dihydrotestosterone on ICPs of uRPL Women’s Lymphocytes

2.3.2. Influence of β-Estradiol on ICPs of uRPL Women’s Lymphocytes

2.3.3. Influence of Progesterone on ICPs of uRPL Women’s Lymphocytes

3. Discussion

3.1. Dihydrotestosterone Influence on ICP Expression on Immune Cells of Healthy Pregnant Women and uRPL Patients

3.2. β-Estradiol Influence on ICP Expression in Immune Cells of Healthy Pregnant Women and uRPL Patients

3.3. Progesterone Influence on ICP Expression on Immune Cells of Healthy Pregnant Women and uRPL Patients

3.4. Limitations of the Study

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Population

4.2. Pregnant Women

4.3. Recurrent Pregnancy Loss (RPL) Women

4.4. Sample Isolation and Preparation

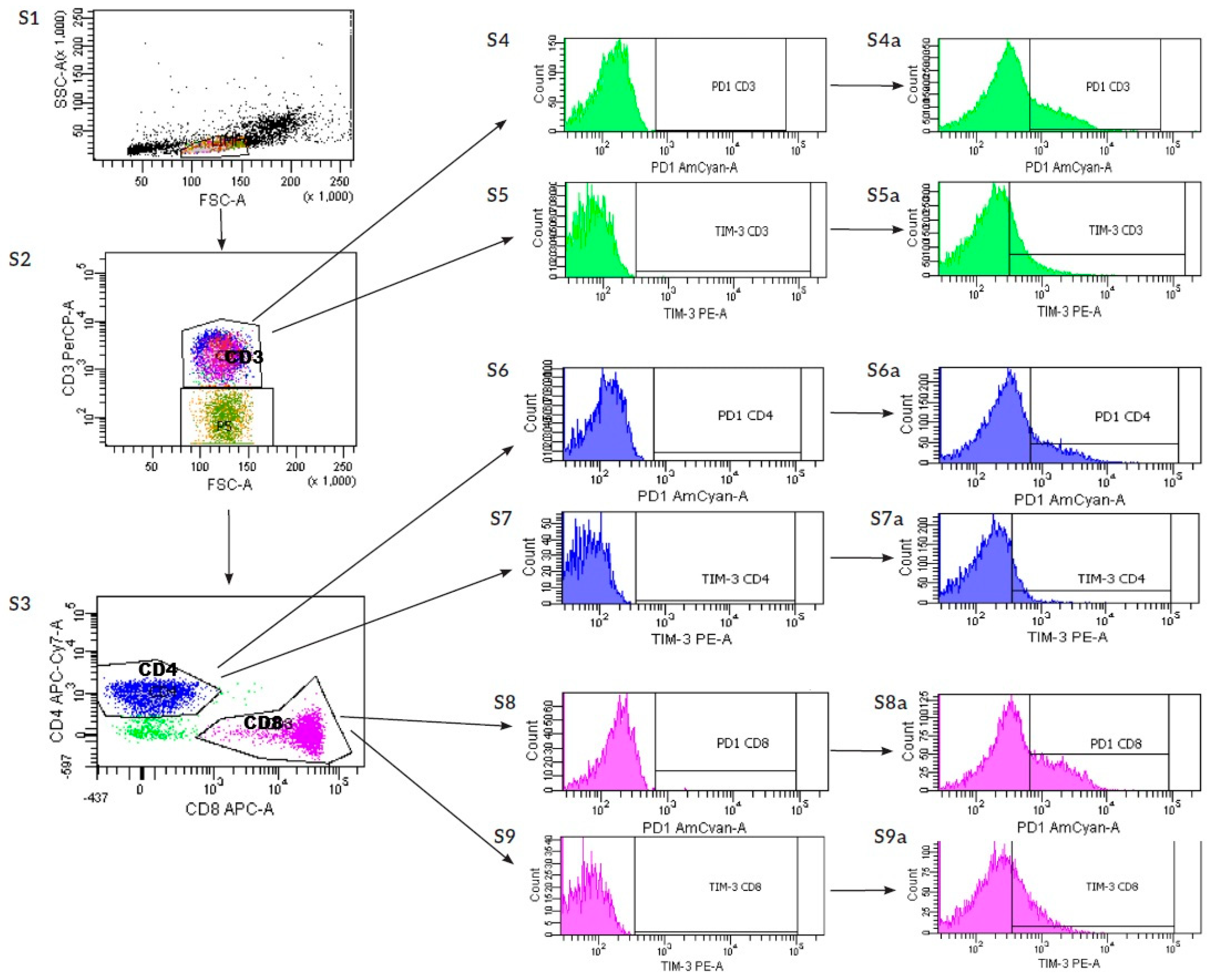

4.5. Flow Cytometry Staining

4.6. Determination of Anti-HLA-Y Antibodies

4.7. Institutional Review Board Statement

4.8. Statistical Analysis

4.9. Graphics

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Wang, J.; Han, T.; Zhu, X. Role of maternal-fetal immune tolerance in the establishment and maintenance of pregnancy. Chin. Med. J. 2024, 137, 1399–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petroff, M.G. Immune interactions at the maternal–fetal interface. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2011, 88, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, H.S.; Pal, L.; Seli, E. Recurrent early pregnancy loss. In Speroff’s Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility, 9th ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 1174–1204. [Google Scholar]

- Genovese, H.G.; McQueen, D.B. The prevalence of sporadic and recurrent pregnancy loss. Fertil. Steril. 2023, 120, 934–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.-J.; Muyayalo, K.P.; Luo, J.; Huang, D.; Mor, G.; Liao, A.-H. Next generation of immune checkpoint molecules in maternal-fetal immunity. Immunol. Rev. 2022, 308, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, Y.; Chang, Y.; Dong, B.; Kong, B.; Qu, X. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase levels at the normal and recurrent spontaneous abortion fetal–maternal interface. J. Int. Med. Res. 2013, 41, 1135–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Huang, Y.; Huang, G.; Chen, Z.; Tang, J.; Pan, L.; Lv, J.; Long, A.; Wang, R.; Chen, Z.; et al. Effect of the IDO Gene on Pregnancy in Mice with Recurrent Pregnancy Loss. Reprod. Sci. 2021, 28, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-H.; Sun, H.-X. Immune checkpoint molecules in pregnancy: Focus on regulatory T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2020, 50, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Sun, F.; Li, M.; Qian, J.; Chen, C.; Wang, M.; Zang, X.; Li, D.; Yu, M.; Du, M. The appropriate frequency and function of decidual Tim-3+CTLA-4+CD8+ T cells are important in maintaining normal pregnancy. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lee, S.Y.; Pearce, E.N. Assessment and treatment of thyroid disorders in pregnancy and the postpartum period. Nature reviews. Endocrinology 2022, 18, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrońska, K.; Hałasa, M.; Szczuko, M. The Role of the Immune System in the Course of Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis: The Current State of Knowledge. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miklos, D.B.; Kim, H.T.; Zorn, E.; Hochberg, E.P.; Guo, L.; Mattes-Ritz, A.; Viatte, S.; Soiffer, R.J.; Antin, J.H.; Ritz, J. Antibody response to DBY minor histocompatibility antigen is induced after allogeneic stem cell transplantation and in healthy female donors. Blood 2004, 103, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, P.H.; Liu, J.A.; Seddu, K.; Klein, S.L. Sex hormone signaling and regulation of immune function. Immunity 2023, 56, 2472–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, H.; Zhang, Y.; Fatunbi, J.; Luu, T.; Kwak-Kim, J. The impact of reproductive hormones on T cell immunity; normal and assisted reproductive cycles. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2024, 165, 104295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovats, S. Estrogen receptors regulate innate immune cells and signaling pathways. Cell. Immunol. 2015, 294, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleicher, N.; Weghofer, A.; Barad, D.H. The role of androgens in follicle maturation and ovulation induction: Lessons from in vitro fertilization. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2011, 9, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Hong, L.; Nie, M.; Wang, Q.; Fang, Y.; Dai, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Wang, S.; Yin, C.; Yang, X. The effect of dehydroepiandrosterone supplementation on ovarian response is associated with androgen receptor in diminished ovarian reserve women. J. Ovarian Res. 2017, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Naik, S.; Lepine, S.; Nagels, H.E.; Siristatidis, C.S.; Kroon, B.; McDowell, S. Androgens (dehydroepiandrosterone or testosterone) for women undergoing assisted reproduction. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 6, CD009749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jain, M.; Fang, E.; Singh, M. Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) Techniques. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, H.S.; Steffensen, R.; Varming, K.; Van Halteren, A.G.; Spierings, E.; Ryder, L.P.; Goulmy, E.; Christiansen, O.B. Association of HY-restricting HLA class II alleles with pregnancy outcome in patients with recurrent miscarriage subsequent to a firstborn boy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009, 18, 1684–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeve, Y.B.; Davies, W. Evidence-based management of recurrent miscarriages. J. Hum. Reprod. Sci. 2014, 7, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stavridis, K.; Kastora, S.L.; Triantafyllidou, O.; Mavrelos, D.; Vlahos, N. Effectiveness of progesterone rescue in women presenting low circulating progesterone levels around the day of embryo transfer: A systematic review and meta-analysis Stavridis. Fertil. Steril. 2023, 119, 954–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garutti, M.; Lambertini, M.; Puglisi, F. Checkpoint inhibitors, fertility, pregnancy, and sexual life: A systematic review. ESMO Open 2021, 6, 100276, Erratum in ESMO Open 2021, 6, 100291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak-Kim, J.; Bao, S.; Lee, S.K.; Kim, J.W.; Gilman-Sachs, A. Immunological modes of pregnancy loss: Inflammation, immune effectors, and stress. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2014, 72, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garmendia, J.V.; De Sanctis, C.V.; Hajdúch, M.; De Sanctis, J.B. Exploring the Immunological Aspects and Treatments of Recurrent Pregnancy Loss and Recurrent Implantation Failure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zych, M.; Roszczyk, A.; Dąbrowski, F.; Kniotek, M.; Zagożdżon, R. Soluble Forms of Immune Checkpoints and Their Ligands as Potential Biomarkers in the Diagnosis of Recurrent Pregnancy Loss—A Preliminary Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zych, M.; Kniotek, M.; Roszczyk, A.; Dąbrowski, F.; Jędra, R.; Zagożdżon, R. Surface Immune Checkpoints as Potential Biomarkers in Physiological Pregnancy and Recurrent Pregnancy Loss. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elena, M.; Von Amsberg, G.; Janning, M.; Loges, S. Influence of Androgens on Immunity to Self and Foreign: Effects on Immunity and Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 540157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, N.J.; Zhou, P.; Ong, H.; Kovacs, W.J. Testosterone induces expression of transforming growth factor-beta 1 in the murine thymus. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1993, 45, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gubbels Bupp, M.R.; Jorgensen, T.N. Androgen-Induced Immunosuppression. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 370132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walecki, M.; Eisel, F.; Klug, J.; Baal, N.; Paradowska-Dogan, A.; Wahle, E.; Hackstein, H.; Meinhardt, A.; Fijak, M. Androgen receptor modulates Foxp3 expression in CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T-cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 2015, 26, 2845–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Rubinstein, R.; Lines, J.L.; Wasiuk, A.; Ahonen, C.; Guo, Y.; Lu, L.-F.; Gondek, D.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; et al. VISTA: A novel mouse Ig superfamily ligand that negatively regulates T cell responses. J. Exp. Med. 2011, 208, 577–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceeraz, S.; Nowak, E.C.; Noelle, R.J. VISTA: A novel checkpoint regulator for cancer immunotherapy. Immunol. Rev. 2013, 276, 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed Khosroshahi, L.; Parhizkar, F.; Kachalaki, S.; Aghebati-Maleki, A.; Aghebati-Maleki, L. Immune checkpoints and reproductive immunology: Pioneers in the future therapy of infertility related Disorders? Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 99, 107935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meggyes, M.; Máté, Á.; Szekeres-Barthó, J.; Polgar, B. The role of TIM-3/galectin-9 pathway in pregnancy: Implications for immune tolerance. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 843644. [Google Scholar]

- Meggyes, M.; David, N.U.; Mezosi, L.; Vastag, F.; Kevey, D.; Szereday, L. Differential Immune Checkpoint Expression in CD4+ and CD4− NKT Cell Populations During Healthy Pregnancy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Li, Y.H.; Zhou, W.H.; Tao, Y.; Wang, S.C.; Jiang, Y.L.; Zhang, D.; Piao, H.L.; Fu, Q.; Li, D.J.; Du, M.R. The Galectin-9/Tim-3 pathway is involved in the regulation of NK cell function at the maternal-fetal interface in early pregnancy. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2016, 13, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yu, N.; Kwak-Kim, J.; Bao, S. Unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss: Novel causes and advanced treatment. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2023, 155, 103785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, S.; Vomstein, K.; Reiser, E.; Tollinger, S.; Kyvelidou, C.; Feil, K.; Toth, B. NK and T Cell Subtypes in the Endometrium of Patients with Recurrent Pregnancy Loss and Recurrent Implantation Failure: Implications for Pregnancy Success. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi, H.; Soltani-Zangbar, M.S.; Yousefi, M.; Baradaran, B.; Bromand, S.; Aghebati-Maleki, L.; Szekeres-Bartho, J. The evaluation of PD-1 and Tim-3 expression besides their related miRNAs in PBMCs of women with recurrent pregnancy loss. Immunol. Lett. 2024, 266, 106837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnie, S.A.; Waltner, O.G.; Zhang, P.; Takahashi, S.; Nemychenkov, N.S.; Ensbey, K.S.; Schmidt, C.R.; Legg, S.R.W.; Comstock, M.; Boiko, J.R.; et al. TIM-3+ CD8 T cells with a terminally exhausted phenotype retain functional capacity in hematological malignancies. Sci. Immunol. 2024, 9, eadg1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kowalczyk, E.; Kniotek, M.; Korczak-Kowalska, G.; Borysowski, J. Progesterone-induced blocking factor and interleukin 4 as novel therapeutics in the treatment of recurrent pregnancy loss. Med. Hypotheses 2022, 168, 110968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.C.; Joller, N.; Kuchroo, V.K. Lag-3, Tim-3, and TIGIT: Co-inhibitory Receptors with Specialized Functions in Immune Regulation. Immunity 2016, 44, 989–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, K.L.; Garrett, K.P.; Thompson, L.F.; Rossi, M.I.D.; Payne, K.J.; Kincade, P.W. Identification of very early lymphoid precursors in bone marrow and their regulation by estrogen. Nat. Immunol. 2001, 2, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallvé-Juanico, J.; Houshdaran, S.; Giudice, L.C. The endometrial immune environment of women with endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2019, 25, 564–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, D.A.; Greaves, E.; Critchley, H.O.D.; Saunders, P.T.K. Estrogen-dependent regulation of human uterine natural killer cells promotes vascular remodelling via secretion of CCL2. Hum. Reprod. 2015, 30, 1290–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parisi, F.; Fenizia, C.; Introini, A.; Zavatta, A.; Scaccabarozzi, C.; Biasin, M.; Savasi, V. The pathophysiological role of estrogens in the initial stages of pregnancy: Molecular mechanisms and clinical implications for pregnancy outcome from the periconceptional period to end of the first trimester. Hum. Reprod. Update 2023, 29, 699–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Elze, R.; Halkias, J. Mechanisms of Fetal T Cell Tolerance and Immune Regulation. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanczyk, M.J.; Hopke, C.; Arthur, A. Vandenbark, Halina Offner, Treg suppressive activity involves estrogen-dependent expression of programmed death-1 (PD-1). Int. Immunol. 2007, 19, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miko, E.; Meggyes, M.; Doba, K.; Barakonyi, A.; Szereday, L. Immune Checkpoint Molecules in Reproductive Immunology. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruhashi, T.; Sugiura, D.; Okazaki, I.; Okazaki, T. LAG-3: From molecular functions to clinical applications. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e001014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-T.; Workman, C.J.; Flies, D.; Pan, X.; Marson, A.L.; Zhou, G.; Hipkiss, E.L.; Ravi, S.; Kowalski, J.; Levitsky, H.I.; et al. Role of LAG-3 in Regulatory T Cells. Immunity 2004, 21, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, C.J.; Dugger, K.J.; Vignali, D.A.A. Cutting edge: Molecular analysis of the negative regulatory function of lymphocyte activation gene-3. J. Immunol. 2002, 169, 5392–5395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joller, N.; Anderson, A.C.; Kuchroo, V.K. LAG-3, TIM-3, and TIGIT: Distinct functions in immune regulation. Immunity 2024, 57, 206–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cui, L.; Sun, F.; Meng, X.; Luo, Y.; Qian, J.; Wang, S. LAG-3 palmitoylation-inducing dysfunction of decidual CD4+T cells is associated with recurrent pregnancy loss. Mol. Med. 2025, 31, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

or decrease—

or decrease— . Created with Microsoft Paint 3D.

. Created with Microsoft Paint 3D.

or decrease—

or decrease— . Created with Microsoft Paint 3D.

. Created with Microsoft Paint 3D.

for “increase” or

for “increase” or  “decrease”. Created with Microsoft Paint 3D.

“decrease”. Created with Microsoft Paint 3D.

for “increase” or

for “increase” or  “decrease”. Created with Microsoft Paint 3D.

“decrease”. Created with Microsoft Paint 3D.

| Median and Q1–Q4 Quartile | Pregnant Women | RPL Women | p-Value Pregnant vs. RPL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [years] | Median | 30 | 34 | p = 0.26 |

| Q1 | 25 | 22 | ||

| Q4 | 39 | 40 | ||

| BMI (body mass index) | Median | 21.6 | 21.8 | p = 0.5 |

| Q1 | 16.7 | 17.9 | ||

| Q4 | 31.4 | 37.2 | ||

| Number of full-term pregnancies | Median | 1 | 0 | p = 0.027 * |

| Q1 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Q4 | 3 | 0 | ||

| Number of miscarriages | Median | 0 | 3 | p = 0.0001 ** |

| Q1 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Q4 | 0 | 5 | ||

| Pregnancy duration (weeks) | Median | 12.8 | 8.8 | p = 0.1 |

| Q1 | 11.7 | 4.0 | ||

| Q4 | 14.6 | 13.6 | ||

| The occurrence of chronic diseases | ||||

| Pregnant women | RPL women | |||

| Diabetes | 10% | 5% | ||

| Endometriosis | 0% | 0% | ||

| Insulin resistance | 5% | 5% | ||

| Hashimoto’s disease | 10% | 20% | ||

| Polycystic ovary syndrome | 10% | 0% | ||

| Alloimmunization | 5% | 5% | ||

| Diet supplements and folic acid administration before pregnancy and during pregnancy | ||||

| Folic acid administration | 65% | 80% | ||

| Medicine and dietary supplement administration before pregnancy | 60% | 75% | ||

| Salicylic acid and dietary supplement administration during pregnancy | 90% | 75% | ||

| No medicine or dietary supplement administration before pregnancy | 40% | 25% | ||

| No medicine or dietary supplement administration during pregnancy | 10% | 25% | ||

| Antibody | Fluorochrome | Clone | Volume | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-CD3 | PreCP | Sk7 | 2 µL | Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA |

| Anti-CD4 | APC-Cy7 | RPA-T4 | 0.5 µL | Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA |

| Anti-CD8 | APC | SK-1 | 0.5 µL | Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA |

| Anti-CD25 | FITC | CD25-4E3 | 1 µL | Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA |

| Anti-CD127 | BV450 | HIL-7R-M21 | 0.5 µL | Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA |

| Anti-CD56 | PE-Cy7 | B159 | 1 µL | Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA |

| Experiment | Antibody | Fluorochrome | Clone | Volume | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st tube | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2nd tube | Anti-PD1 | BV480 | EH12.1 | 1 µL | Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA |

| Anti-Tim3 | PE | 7D3 | 0.5 µL | Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA | |

| 3rd tube | Anti-Lag3 | BV480 | T47-530 | 1 µL | Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA |

| 4th tube | Anti-TIGIT | PE | 741182 | 1 µL | Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA |

| Anti-VISTA | BV480 | 1 µL | Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zych, M.; Roszczyk, A.; Zakrzewska, M.; Zagożdżon, R.; Pączek, L.; Dąbrowski, F.A.; Kniotek, M.J. Sex Hormones-Mediated Modulation of Immune Checkpoints in Pregnancy and Recurrent Pregnancy Loss. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1265. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031265

Zych M, Roszczyk A, Zakrzewska M, Zagożdżon R, Pączek L, Dąbrowski FA, Kniotek MJ. Sex Hormones-Mediated Modulation of Immune Checkpoints in Pregnancy and Recurrent Pregnancy Loss. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(3):1265. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031265

Chicago/Turabian StyleZych, Michał, Aleksander Roszczyk, Marzenna Zakrzewska, Radosław Zagożdżon, Leszek Pączek, Filip Andrzej Dąbrowski, and Monika Joanna Kniotek. 2026. "Sex Hormones-Mediated Modulation of Immune Checkpoints in Pregnancy and Recurrent Pregnancy Loss" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 3: 1265. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031265

APA StyleZych, M., Roszczyk, A., Zakrzewska, M., Zagożdżon, R., Pączek, L., Dąbrowski, F. A., & Kniotek, M. J. (2026). Sex Hormones-Mediated Modulation of Immune Checkpoints in Pregnancy and Recurrent Pregnancy Loss. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(3), 1265. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031265