Circularization and Ribosome Recycling: From Polysome Topology to Translational Control

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Morphology of Polysomes and mRNA Topology

2.1. Electron Microscopy Approaches

2.1.1. Classical EM Visualization of mRNA Ends

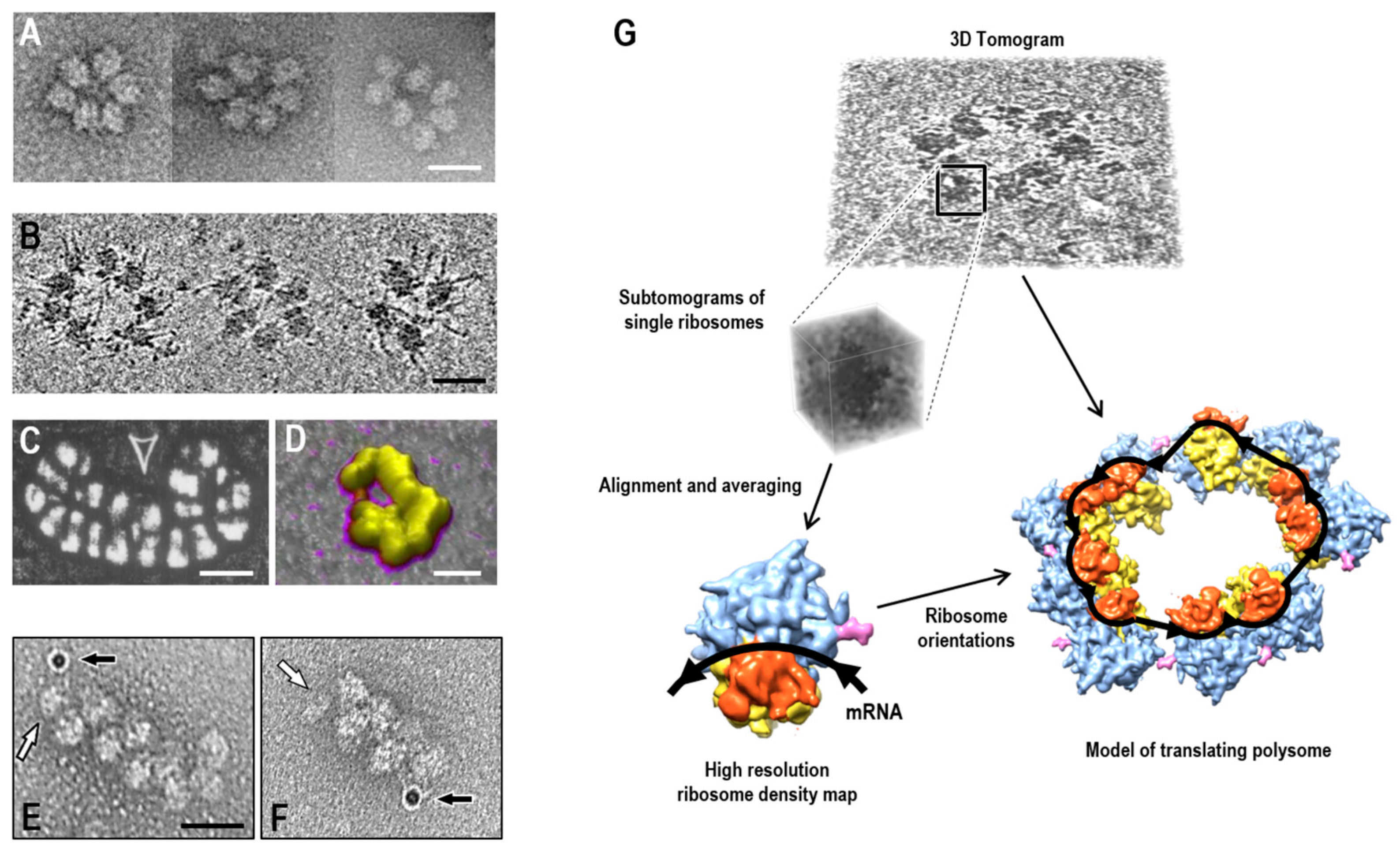

2.1.2. Cryo-Electron Tomography and Ribosome Orientation Mapping

2.2. Atomic Force Microscopy of Polysomes

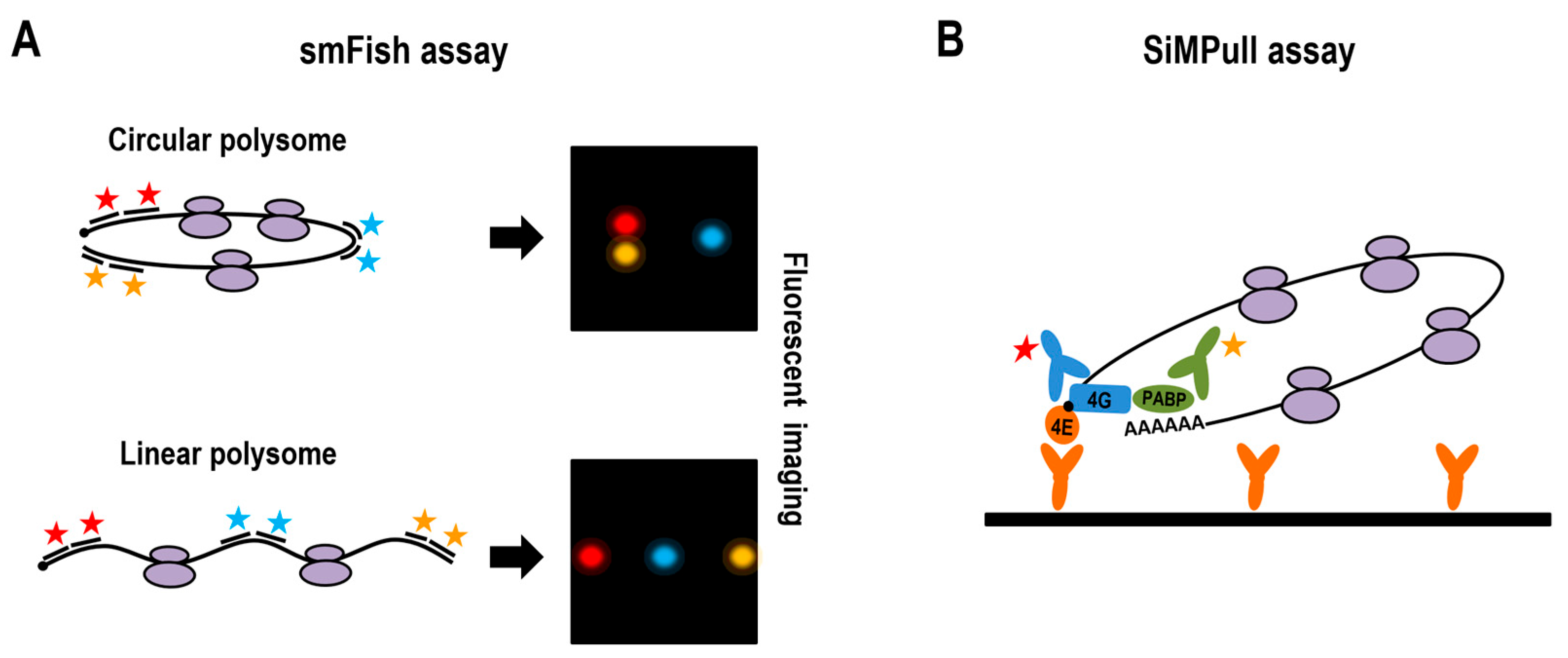

2.3. Fluorescence Microscopy of mRNA Conformation

2.3.1. smFISH Mapping of mRNA Architecture

2.3.2. SINAPS Imaging of Translating Polysomes

2.3.3. Estimating Circular Polysome Frequency with SiMPull Assay

3. Functional Cyclization and Ribosome Recycling

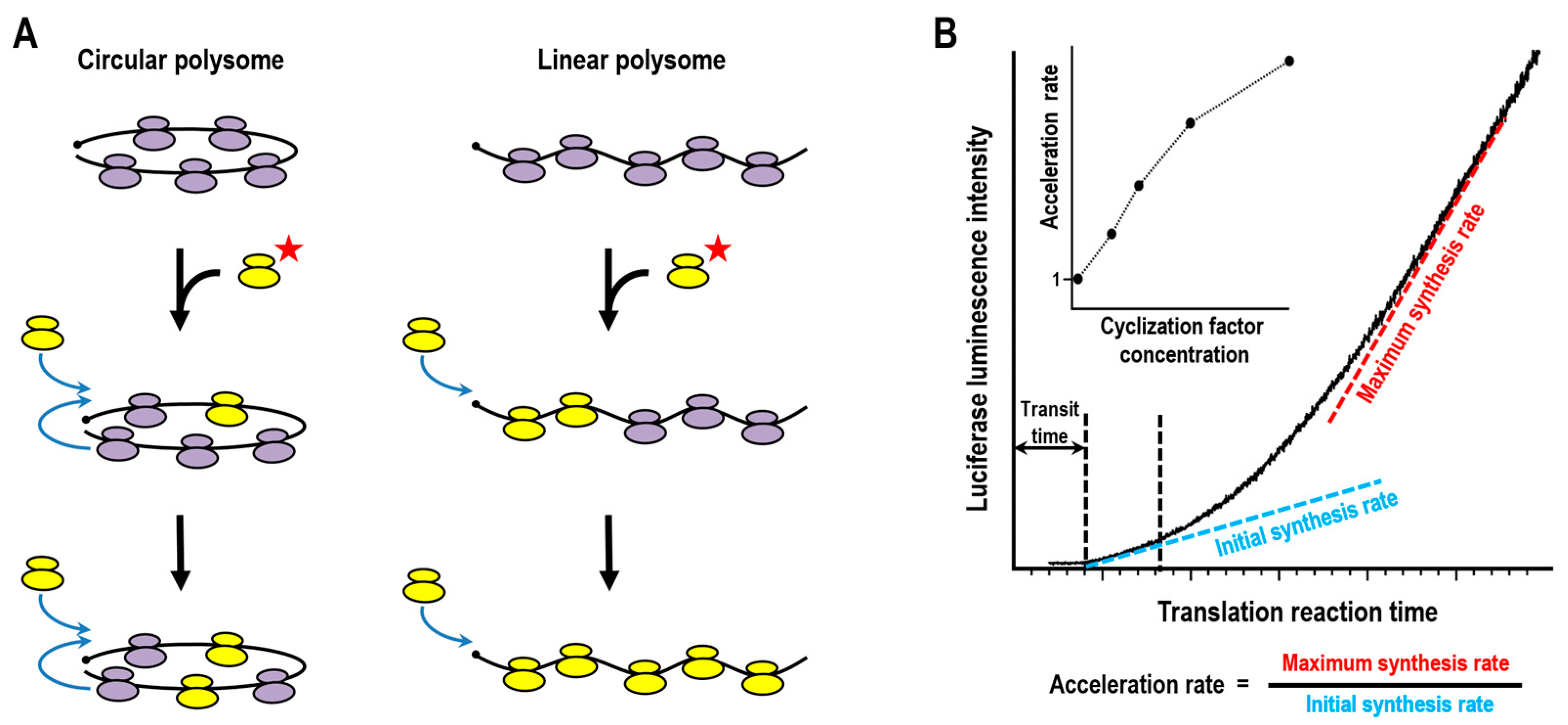

3.1. Ribosome Turnover in Polysomes

3.2. Kinetic Analyses of Closed-Loop-Assisted Reinitiation

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Warner, J.R.; Rich, A.; Hall, C.E. Electron microscope studies of ribosomal clusters synthesizing hemoglobin. Science 1962, 138, 1399–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, A.; Warner, J.R.; Goodman, H.M. The structure and function of polyribosomes. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1963, 28, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathias, A.P.; Williamson, R.; Huxley, H.E.; Page, S. Occurrence and Function of Polysomes in Rabbit Reticulocytes. J. Mol. Biol. 1964, 9, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, E.; Kuff, E.L. Substructure and configuration of ribosomes isolated from mammalian cells. J. Mol. Biol. 1966, 22, 23–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipps, G.R. Haemoglobin synthesis and polysomes in intact reticulocytes. Nature 1965, 205, 567–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, A. Poly (A) metabolism and translation: The closed-loop model. In Translational Control; Hershey, J.W.B., Mathews, M.B., Sonenberg, N., Eds.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 451–480. [Google Scholar]

- Preiss, T.; Hentze, M.W. From factors to mechanisms: Translation and translational control in eukaryotes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1999, 9, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, A.; Favreau, M. Possible involvement of poly(A) in protein synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983, 11, 6353–6368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palatnik, C.M.; Wilkins, C.; Jacobson, A. Translational control during early Dictyostelium development: Possible involvement of poly(A) sequences. Cell 1984, 36, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallie, D.R. The cap and poly(A) tail function synergistically to regulate mRNA translational efficiency. Genes Dev. 1991, 5, 2108–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iizuka, N.; Najita, L.; Franzusoff, A.; Sarnow, P. Cap-dependent and cap-independent translation by internal initiation of mRNAs in cell extracts prepared from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994, 14, 7322–7330. [Google Scholar]

- Tarun, S.Z., Jr.; Sachs, A.B. A common function for mRNA 5′ and 3′ ends in translation initiation in yeast. Genes Dev. 1995, 9, 2997–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarun, S.Z., Jr.; Sachs, A.B. Association of the yeast poly(A) tail binding protein with translation initiation factor eIF-4G. EMBO J. 1996, 15, 7168–7177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, S.E.; Hillner, P.E.; Vale, R.D.; Sachs, A.B. Circularization of mRNA by eukaryotic translation initiation factors. Mol. Cell 1998, 2, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.; Tanguay, R.L.; Balasta, M.L.; Wei, C.C.; Browning, K.S.; Metz, A.M.; Goss, D.J.; Gallie, D.R. Translation initiation factors eIF-iso4G and eIF-4B interact with the poly (A)-binding protein and increase its RNA binding activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 16247–16255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imataka, H.; Gradi, A.; Sonenberg, N. A newly identified N-terminal amino acid sequence of human eIF4G binds poly(A)-binding protein and functions in poly (A)-dependent translation. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 7480–7489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito Querido, J.; Díaz-López, I.; Ramakrishnan, V. The molecular basis of translation initiation and its regulation in eukaryotes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 168–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archer, S.K.; Shirokikh, N.E.; Hallwirth, C.V.; Beilharz, T.H.; Preiss, T. Probing the closed-loop model of mRNA translation in living cells. RNA Biol. 2015, 12, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dallner, G.; Siekevitz, P.; Palade, G.E. Biogenesis of endoplasmic reticulum membranes: I. Structural and chemical differentiation in developing rat hepatocyte. J. Cell. Biol. 1966, 30, 73–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, A.K.; Kahn, L.E.; Bourne, C.M. Circular polysomes predominate on the rough endoplasmic reticulum of somatotropes and mammotropes in the rat anterior pituitary. Am. J. Anat. 1987, 178, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, A.K.; Bourne, C.M. Shape of large bound polysomes in cultured fibroblasts and thyroid epithelial cells. Anat. Rec. 1999, 255, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neusiedler, J.; Mocquet, V.; Limousin, T.; Ohlmann, T.; Morris, C.; Jalinot, P. INT6 interacts with MIF4GD/SLIP1 and is necessary for efficient histone mRNA translation. RNA 2012, 18, 1163–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Moeller, H.; Lerner, R.; Ricciardi, A.; Basquin, C.; Marzluff, W.F.; Conti, E. Structural and biochemical studies of SLIP1-SLBP identify DBP5 and eIF3g as SLIP1-binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, 7960–7971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, I.I.; Vassilenko, K.S.; Terenin, I.M.; Kalinina, N.O.; Agol, V.I.; Dmitriev, S.E. Non-canonical translation initiation mechanisms employed by eukaryotic viral mRNAs. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2021, 86, 1060–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonina, Z.A.; Myasnikov, A.G.; Shirokov, V.A.; Klaholz, B.P.; Spirin, A.S. Formation of circular polyribosomes on eukaryotic mRNA without cap-structure and poly(A)-tail: A cryo electron tomography study. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 9461–9469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madin, K.; Sawasaki, T.; Kamura, N.; Takai, K.; Ogasawara, T.; Yazaki, K.; Takei, T.; Miura, K.; Endo, Y. Formation of circular polyribosomes in wheat germ cell-free protein synthesis system. FEBS Lett. 2004, 562, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayr, C. Regulation by 3′-Untranslated Regions. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2017, 51, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakim, H.; Fabian, M.R. Communication Is Key: 5′-3′ Interactions that Regulate mRNA Translation and Turnover. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1203, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rogers, D.W.; Bottcher, M.A.; Traulsen, A.; Greig, D. Ribosome reinitiation can explain length-dependent translation of messenger RNA. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, E.; Stansfield, I.; Romano, M.C. Ribosome recycling induces optimal translation rate at low ribosomal availability. J. R. Soc. Interface 2014, 11, 20140589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.K.; Gilbert, W.V. mRNA length-sensing in eukaryotic translation: Reconsidering the “closed loop” and its implications for translational control. Curr. Genet. 2017, 63, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicens, Q.; Kieft, J.S.; Rissland, O.S. Revisiting the Closed-Loop Model and the Nature of mRNA 5′-3′ Communication. Mol. Cell 2018, 72, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelletier, J.; Sonenberg, N. The Organizing Principles of Eukaryotic Ribosome Recruitment. Annu. Rev. BioChem. 2019, 88, 307–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekhina, O.M.; Terenin, I.M.; Dmitriev, S.E.; Vassilenko, K.S. Functional cyclization of eukaryotic mRNAs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazaki, K.; Yoshida, T.; Wakiyama, M.; Miura, K.I. Polysomes of eukaryotic cells observed by electron microscopy. J. Electron Microsc. 2000, 49, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopeina, G.S.; Afonina, Z.A.; Gromova, K.V.; Shirokov, V.A.; Vasiliev, V.D.; Spirin, A.S. Step-wise formation of eukaryotic double-row polyribosomes and circular translation of polysomal mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, 2476–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baymukhametov, T.N.; Lyabin, D.N.; Chesnokov, Y.M.; Sorokin, I.I.; Pechnikova, E.V.; Vasiliev, A.L.; Afonina, Z.A. Polyribosomes of circular topology are prevalent in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 908–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Wakiyama, M.; Yazaki, K.; Miura, K.I. Transmission electron and atomic force microscopic observation of polysomes on carboncoated grids prepared by surface spreading. Microscopy 1997, 46, 503–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viero, G.; Lunelli, L.; Passerini, A.; Bianchini, P.; Gilbert, R.J.; Bernabò, P.; Tebaldi, T.; Diaspro, A.; Pederzolli, C.; Quattrone, A. Three distinct ribosome assemblies modulated by translation are the building blocks of polysomes. J. Cell Biol. 2015, 208, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonina, Z.; Myasnikov, A.G.; Khabibullina, N.F.; Belorusova, A.Y.; Menetret, J.F.; Vasiliev, V.D.; Klaholz, B.P.; Shirokov, V.A.; Spirin, A.S. Topology of mRNA chain in isolated eukaryotic double-row polyribosomes. Biochemistry 2013, 78, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, J.; Lin, S.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Q.; Wang, L.; Ramirez-Moya, J.; Du, P.; Kim, W.; Tang, S.; Sliz, P.; et al. mRNA circularization by METTL3–eIF3h enhances translation and promotes oncogenesis. Nature 2018, 561, 556–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.; Shao, S. Ribosomes and cryo-EM: A duet. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2018, 52, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afonina, Z.A.; Shirokov, V.A. Three-dimensional organization of polyribosomes–a modern approach. Biochemistry 2018, 83, S48–S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, F.; Carlson, L.A.; Hartl, F.U.; Baumeister, W.; Grünewald, K. The three-dimensional organization of polyribosomes in intact human cells. Mol. Cell. 2010, 39, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, F.; Etchells, S.A.; Ortiz, J.O.; Elcock, A.H.; Hartl, F.U.; Baumeister, W. The native 3D organization of bacterial polysomes. Cell 2009, 136, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; Taniguchi, R.; Khusainov, I.; Kreysing, J.P.; Welsch, S.; Turoňová, B.; Beck, M. Translation dynamics in human cells visualized at high resolution reveal cancer drug action. Science 2023, 381, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedry, J.; Silva, J.; Vanevic, M.; Fronik, S.; Mechulam, Y.; Schmitt, E.; des Georges, A.; Faller, W.; Förster, F. Visualization of translation reorganization upon persistent ribosome collision stress in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell 2024, 84, 1078–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Chai, P.; Bailey, E.J.; Zhu, C.; Guo, W.; Devarkar, S.D.; Wu, S.; et al. Visualizing the translation landscape in human cells at high resolution. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 10757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; Wagner, J.; Du, W.; Plitzko, J.; Baumeister, W.; Beck, F.; Guo, Q. A transformation clustering algorithm and its application in polyribosomes structural profiling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 9001–9011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashkova, S.; Leake, M.C. Single-molecule fluorescence microscopy review: Shedding new light on old problems. Biosci. Rep. 2017, 37, BSR20170031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adivarahan, S.; Livingston, N.; Nicholson, B.; Rahman, S.; Wu, B.; Rissland, O.S.; Zenklusen, D. Spatial organization of single mRNPs at different stages of the gene expression pathway. Mol. Cell 2018, 72, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.; Park, Y.; Hwang, H.J.; Chang, J.; Kim, Y.K.; Lee, J.B. Single polysome analysis of mRNP. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 618, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haimovich, G.; Gerst, J.E. Single-molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH) for RNA detection in adherent animal cells. Bio-protocal 2018, 8, e3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khong, A.; Parker, R. mRNP architecture in translating and stress conditions reveals an ordered pathway of mRNP compaction. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 4124–4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrani, N.; Ghosh, S.; Mangus, D.A.; Jacobson, A. Translation factors promote the formation of two states of the closed-loop mRNP. Nature 2008, 453, 1276–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.K.; Rojas-Duran, M.F.; Gangaramani, P.; Gilbert, W.V. The ribosomal protein asc1/rack1 is required for efficient translation of short mRNAs. Elife 2016, 5, e11154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morisaki, T.; Lyon, K.; DeLuca, K.F.; DeLuca, J.G.; English, B.P.; Zhang, Z.; Lavis, L.D.; Grimm, J.B.; Viswanathan, S.; Looger, L.L.; et al. Real-time quantification of single RNA translation dynamics in living cells. Science 2016, 352, 1425–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Liu, R.; Xiang, Y.K.; Ha, T. Single-molecule pull-down for studying protein interactions. Nat. Protoc. 2012, 7, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, S.; Faravelli, S.; Voegeli, S.; Becskei, A. Polysome propensity and tunable thresholds in coding sequence length enable differential mRNA stability. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadh9545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baglioni, C.; Vesco, C.; Jacobs-Lorena, M. The role of ribosomal subunits in mammalian cells. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1969, 34, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamson, S.D.; Howard, G.A.; Herbert, E. The ribosome cycle in a reconstituted cell-free system from reticulocytes. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1969, 34, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, E.M.; Winkler, M.M. Regulation of mRNA entry into polysomes. Parameters affecting polysome size and the fraction of mRNA in polysomes. J. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262, 11501–11506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, V.A.; Makeyev, E.V.; Spirin, A.S. Folding of firefly luciferase during translation in a cell-free system. EMBO J. 1994, 13, 3631–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekhina, O.M.; Vassilenko, K.S.; Spirin, A.S. Translation of non-capped mRNAs in a eukaryotic cell-free system: Acceleration of initiation rate in the course of polysome formation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 6547–6559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, W.J.C.; Kayedkhordeh, M.; Cornell, E.V.; Farah, E.; Bellaousov, S.; Rietmeijer, R.; Salsi, E.; Mathews, D.H.; Ermolenko, D.N. mRNAs and lncRNAs intrinsically form secondary structures with short end-to-end distances. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermolenko, D.N.; Mathews, D.H. Making ends meet: New functions of mRNA secondary structure. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2021, 12, e1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerling, N.; Mendez, J.A.; Gomez, E.; Ruiz-Garcia, J. The separation between mRNA-ends is more variable than expected. FEBS Open Bio 2024, 14, 1985–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metkar, M.; Ozadam, H.; Lajoie, B.R.; Imakaev, M.; Mirny, L.A.; Dekker, J.; Moore, M.J. Higher-order organization principles of pre-translational mRNPs. Mol. Cell 2018, 72, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dostie, J.; Dreyfuss, G. Translation is required to remove Y14 from mRNAs in the cytoplasm. Curr. Biol. 2002, 12, 1060–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, E.; Levanon, E.Y. Human housekeeping genes are compact. TRENDS Genet. 2003, 19, 362–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, A.L.; Pasquinelli, A.E. Tales of Detailed Poly(A) Tails. Trends Cell Biol. 2019, 29, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weill, L.; Belloc, E.; Bava, F.A.; Mendez, R. Translational control by changes in poly(A) tail length: Recycling mRNAs. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012, 19, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalba, A.; Coll, O.; Gebauer, F. Cytoplasmic polyadenylation and translational control. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2011, 21, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machida, K.; Shigeta, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Ito, T.; Svitkin, Y.; Sonenberg, N.; Imataka, H. Dynamic interaction of poly(A)-binding protein with the ribosome. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahvejian, A.; Svitkin, Y.V.; Sukarieh, R.; M’Boutchou, M.N.; Sonenberg, N. Mammalian poly(A)-binding protein is a eukaryotic translation initiation factor, which acts via multiple mechanisms. Genes Dev. 2005, 19, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borman, A.M.; Michel, Y.M.; Kean, K.M. Biochemical characterisation of cap-poly(A) synergy in rabbit reticulocyte lysates: The eIF4G-PABP interaction increases the functional affinity of eIF4E for the capped mRNA 5′-end. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 4068–4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushell, M.; Wood, W.; Carpenter, G.; Pain, V.M.; Morley, S.J.; Clemens, M.J. Disruption of the interaction of mammalian protein synthesis eukaryotic initiation factor 4B with the poly(A)-binding protein by caspase- and viral protease-mediated cleavages. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 23922–23928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.C.; Balasta, M.L.; Ren, J.; Goss, D.J. Wheat germ poly(A) binding protein enhances the binding affinity of eukaryotic initiation factor 4F and (iso)4F for cap analogues. BioChem. 1998, 37, 1910–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, X.; Goss, D.J. Wheat germ poly(A)-binding protein increases the ATPase and the RNA helicase activity of translation initiation factors eIF4A, eIF4B, and eIF-iso4F. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 17740–17746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searfoss, A.; Dever, T.E.; Wickner, R. Linking the 3′ poly(A) tail to the subunit joining step of translation initiation: Relations of Pab1p, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5b (Fun12p), and Ski2p-Slh1p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001, 21, 4900–4908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filbin, M.E.; Kieft, J.S. Linking Alpha to Omega: Diverse and dynamic RNA-based mechanisms to regulate gene expression by 5′-to-3′ communication. F1000Res 2016, 5, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Hu, J.; Zhang, H.; Lutz, C.S. A large-scale analysis of mRNA polyadenylation of human and mouse genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, S.; Imai, M.; Kobayashi, T.; Uchida, N.; Katada, T. The eukaryotic polypeptide chain releasing factor (eRF3/GSPT) carrying the translation termination signal to the 3′-Poly(A) tail of mRNA. Direct association of erf3/GSPT with polyadenylate-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 16677–16680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.; Mikhailova, T.; Eliseev, B.; Yeramala, L.; Sokolova, E.; Susorov, D.; Shuvalov, A.; Schaffitzel, C.; Alkalaeva, E. PABP enhances release factor recruitment and stop codon recognition during translation termination. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 7766–7776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancera-Martinez, E.; Brito Querido, J.; Valasek, L.S.; Simonetti, A.; Hashem, Y. ABCE1: A special factor that orchestrates translation at the crossroad between recycling and initiation. RNA Biol. 2017, 14, 1279–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellen, C.U. Translation termination and ribosome recycling in eukaryotes. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2018, 10, a032656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valasek, L.S.; Zeman, J.; Wagner, S.; Beznoskova, P.; Pavlikova, Z.; Mohammad, M.P.; Hronova, V.; Herrmannova, A.; Hashem, Y.; Gunisova, S. Embraced by eIF3: Structural and functional insights into the roles of eIF3 across the translation cycle. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 10948–10968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuvalova, E.; Shuvalov, A.; Al Sheikh, W.; Ivanov, A.V.; Biziaev, N.; Egorova, T.V.; Dmitriev, S.E.; Terenin, I.M.; Alkalaeva, E. Eukaryotic initiation factors eIF4F and eIF4B promote translation termination upon closed-loop formation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, gkaf161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schleich, S.; Strassburger, K.; Janiesch, P.C.; Koledachkina, T.; Miller, K.K.; Haneke, K.; Cheng, Y.S.; Kuechler, K.; Stoecklin, G.; Duncan, K.E.; et al. DENR-MCT-1 promotes translation re-initiation downstream of uORFs to control tissue growth. Nature 2014, 512, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.J.; Makeeva, D.S.; Zhang, F.; Anisimova, A.S.; Stolboushkina, E.A.; Ghobakhlou, F.; Shatsky, I.N.; Dmitriev, S.E.; Hinnebusch, A.G.; Guydosh, N.R. Tma64/eIF2D, Tma20/MCT-1, and Tma22/DENR Recycle Post-termination 40S Subunits In Vivo. Mol. Cell 2018, 71, 761–774.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terenin, I.M.; Smirnova, V.V.; Andreev, D.E.; Dmitriev, S.E.; Shatsky, I.N. A researcher’s guide to the galaxy of IRESs. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2017, 74, 1431–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, K.D.; Patil, D.P.; Zhou, J.; Zinoviev, A.; Skabkin, M.A.; Elemento, O.; Pestova, T.V.; Qian, S.B.; Jaffrey, S.R. 5′ UTR m(6)A Promotes Cap-Independent Translation. Cell 2015, 163, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Fan, X.; Mao, M.; Song, X.; Wu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chen, L.L.; Wang, Y.; et al. Extensive translation of circular RNAs driven by N(6)-methyladenosine. Cell Res. 2017, 27, 626–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunišová, S.; Hronová, V.; Mohammad, M.P.; Hinnebusch, A.G.; Valášek, L.S. Please do not recycle! Translation reinitiation in microbes and higher eukaryotes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 42, 165–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miluzio, A.; Scagliola, A.; Ferrari, I.; Yilmaz, H.; D’Andrea, G.; Cassina, L.; Oliveto, S.; Ricciardi, S.; Boletta, A.; Biffo, S. Recycling of ribosomes at stop codons drives the rate of translation and the transition from proliferation to RESt. Mol. Cell 2025, 85, 4410–4425.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jendruchová, K.; Gaikwad, S.; Poncová, K.; Gunišová, S.; Valášek, L.S.; Hinnebusch, A.G. Differential effects of 40S ribosome recycling factors on reinitiation at regulatory uORFs in GCN4 mRNA are not dictated by their roles in bulk 40S recycling. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherlock, M.E.; Galvis, L.B.; Vicens, Q.; Kieft, J.S.; Jagannathan, S. Principles, mechanisms, and biological implications of translation termination–reinitiation. RNA 2023, 29, 865–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Afonina, Z.A.; Vassilenko, K.S. Circularization and Ribosome Recycling: From Polysome Topology to Translational Control. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1251. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031251

Afonina ZA, Vassilenko KS. Circularization and Ribosome Recycling: From Polysome Topology to Translational Control. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(3):1251. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031251

Chicago/Turabian StyleAfonina, Zhanna A., and Konstantin S. Vassilenko. 2026. "Circularization and Ribosome Recycling: From Polysome Topology to Translational Control" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 3: 1251. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031251

APA StyleAfonina, Z. A., & Vassilenko, K. S. (2026). Circularization and Ribosome Recycling: From Polysome Topology to Translational Control. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(3), 1251. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031251