Molecular Insights into Carbapenem Resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae: From Mobile Genetic Elements to Precision Diagnostics and Infection Control

Abstract

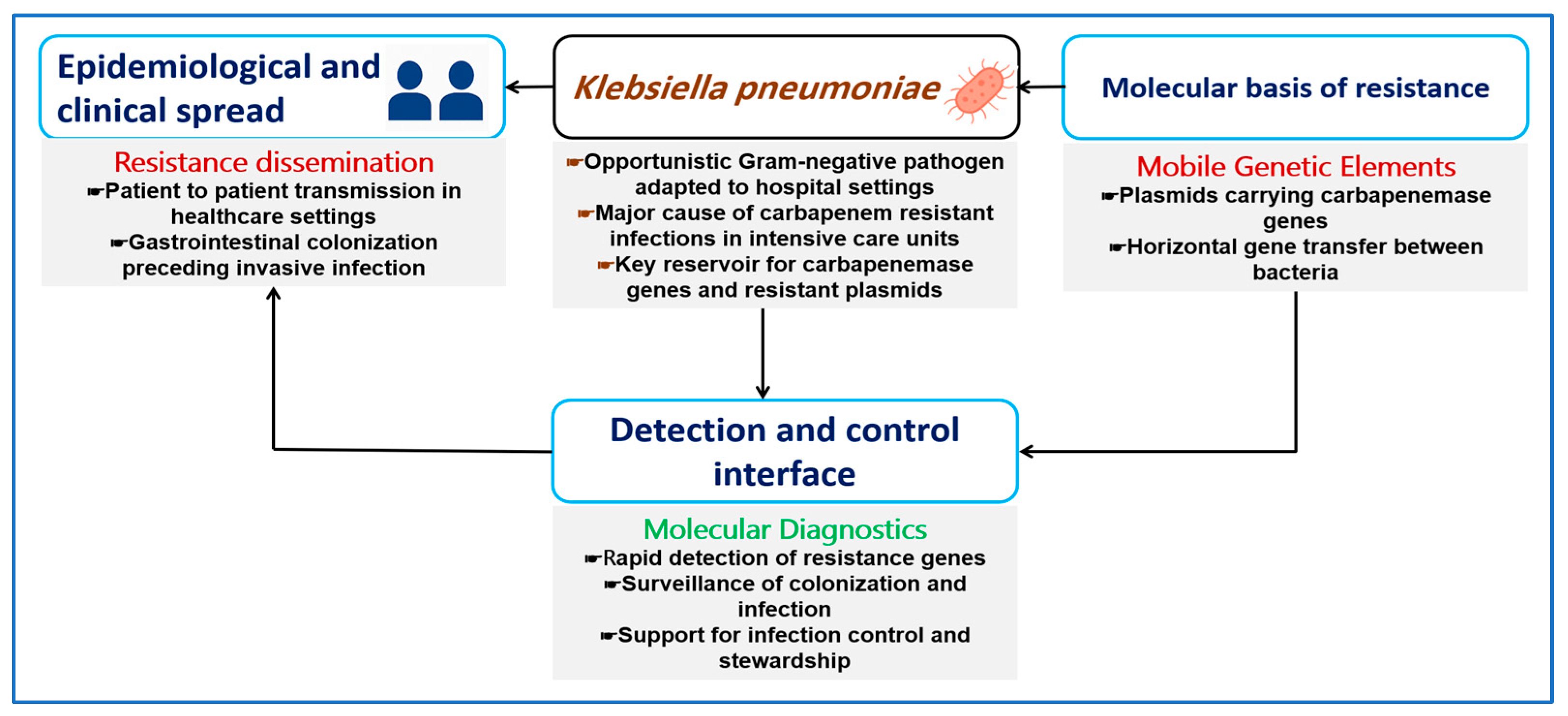

1. Introduction

2. Carbapenem Resistance as a Genetic System in K. pneumoniae

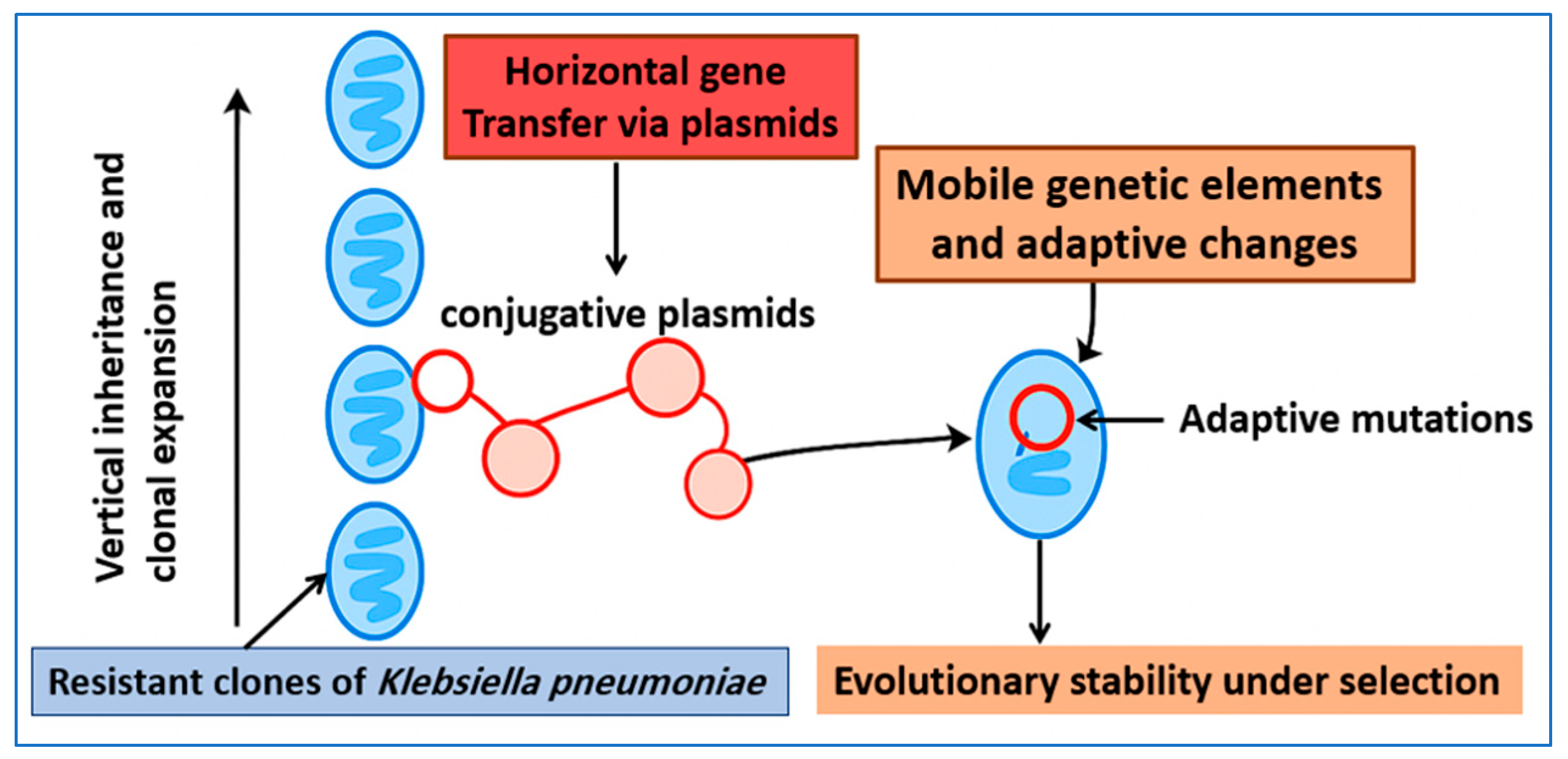

2.1. Vertical and Horizontal Inheritance of Resistance

2.2. Evolutionary Stability of Resistance Determinants

2.3. Fitness Costs and Compensatory Mechanisms

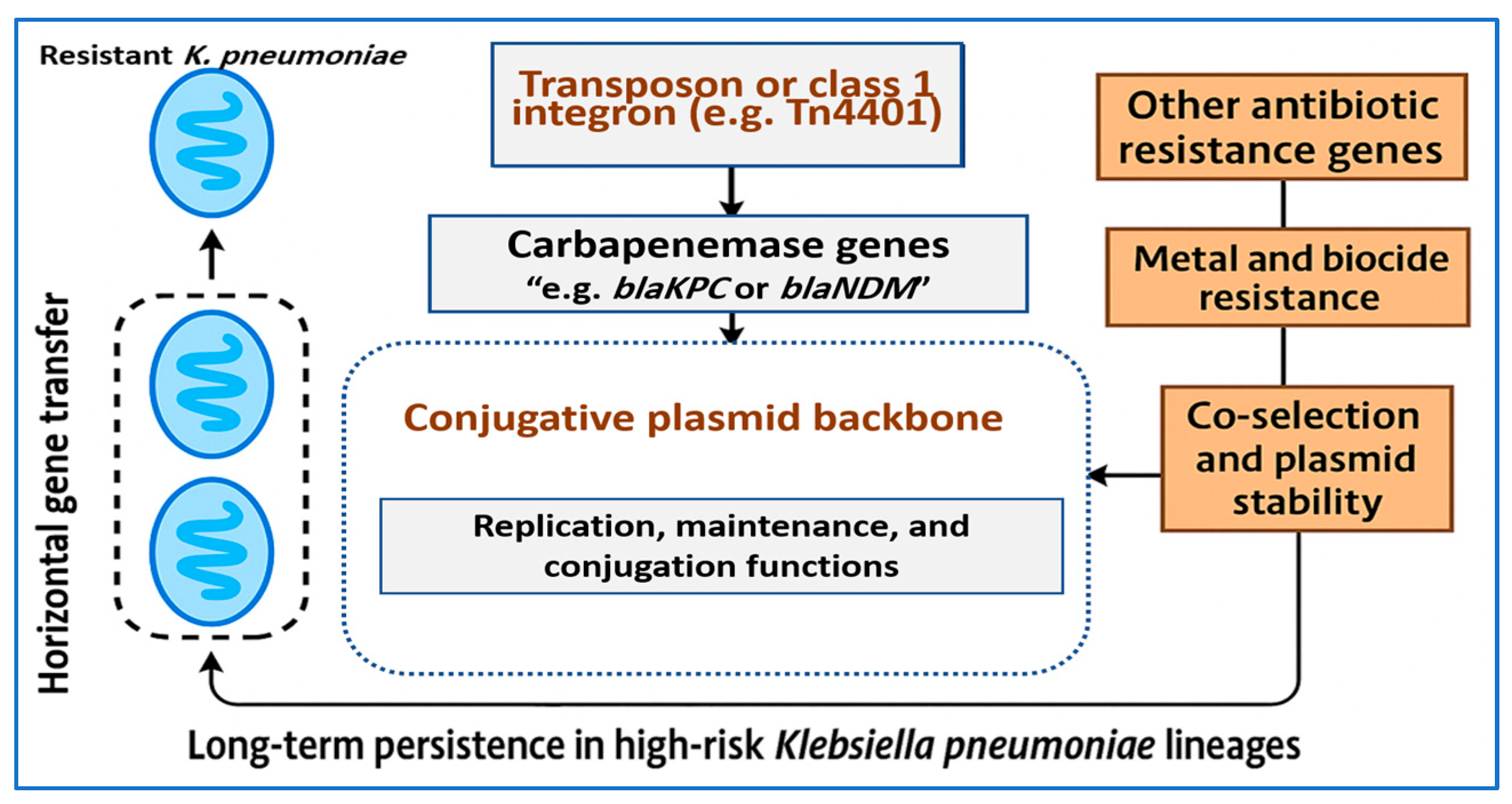

3. Mobile Genetic Elements Driving Carbapenem Resistance

3.1. Plasmid Incompatibility Groups and Epidemic Backbones

3.2. Transposons, Integrons, and Insertion Sequences Surrounding Carbapenemase Genes

3.3. Co Selection and Persistence Mechanisms

3.4. Convergence of Hypervirulence and Carbapenem Resistance (hv-CRKP)

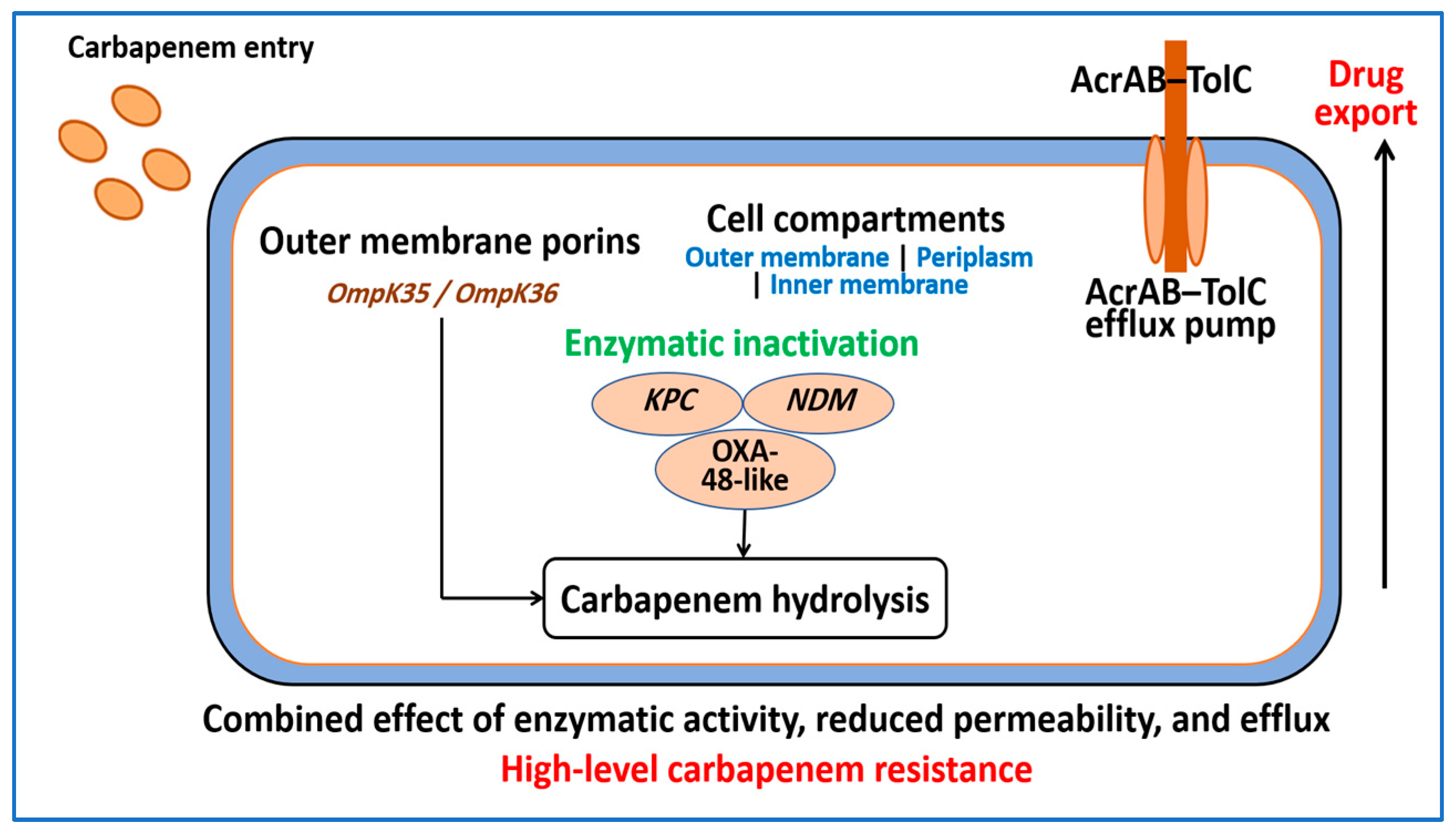

4. Molecular Determinants of Carbapenem Resistance in K. pneumoniae

4.1. Carbapenemase Enzymes

4.2. Porin Alterations and Reduced Outer Membrane Permeability

4.3. Efflux Pumps and Layered Resistance

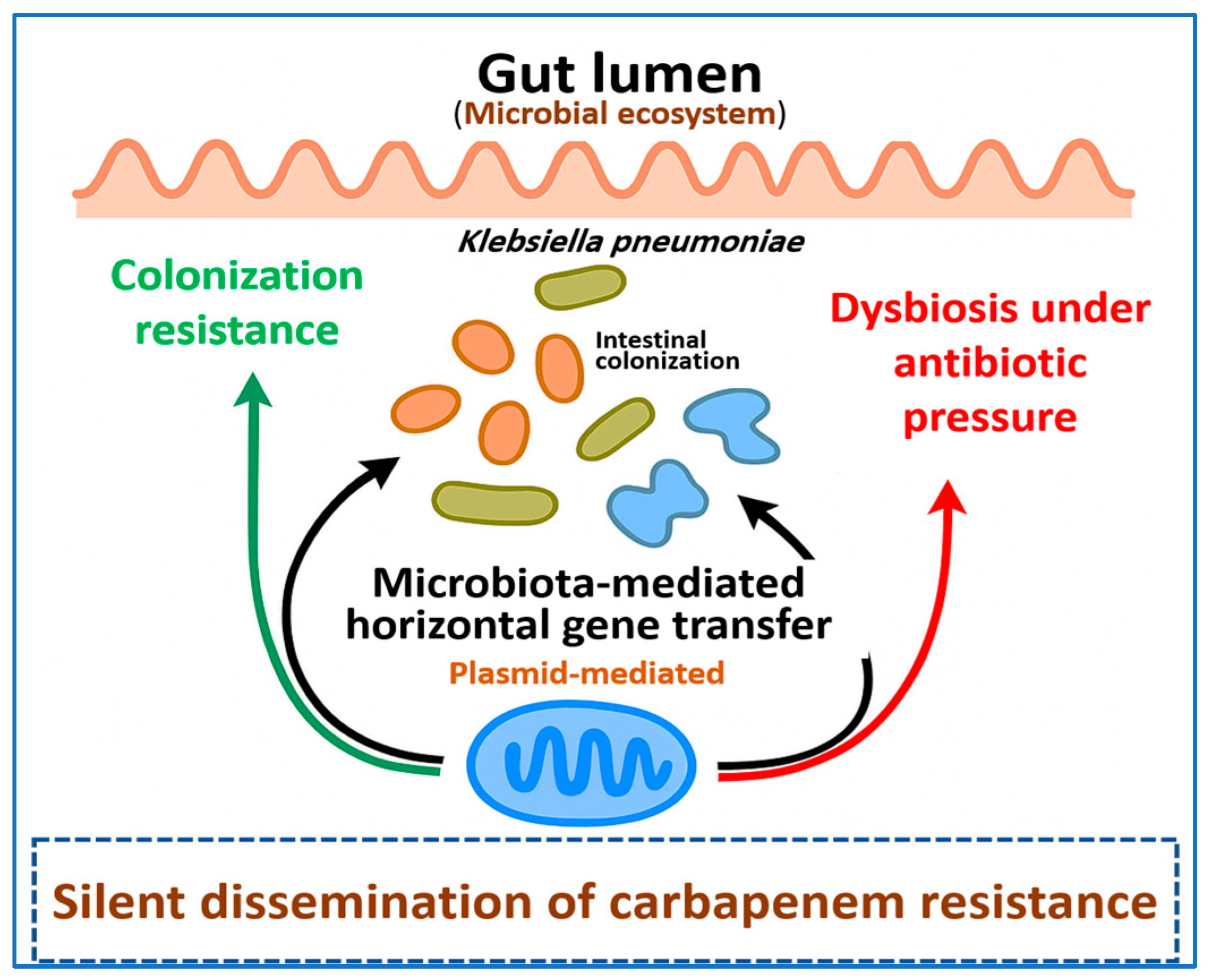

5. The Resistome Beyond the Pathogen: Gut Microbiota and Silent Dissemination

5.1. Intestinal Colonization and Colonization Resistance Reservoirs

5.2. Microbiota Mediated Horizontal Gene Transfer in the Gut

5.3. Antibiotic-Driven Dysbiosis and Silent Dissemination of CRKP

6. Molecular Diagnostics for CRKP

6.1. Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests for Carbapenemase Genes

6.2. Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Assays

6.3. CRISPR-Based Diagnostic Platforms

6.4. Capabilities and Current Limitations

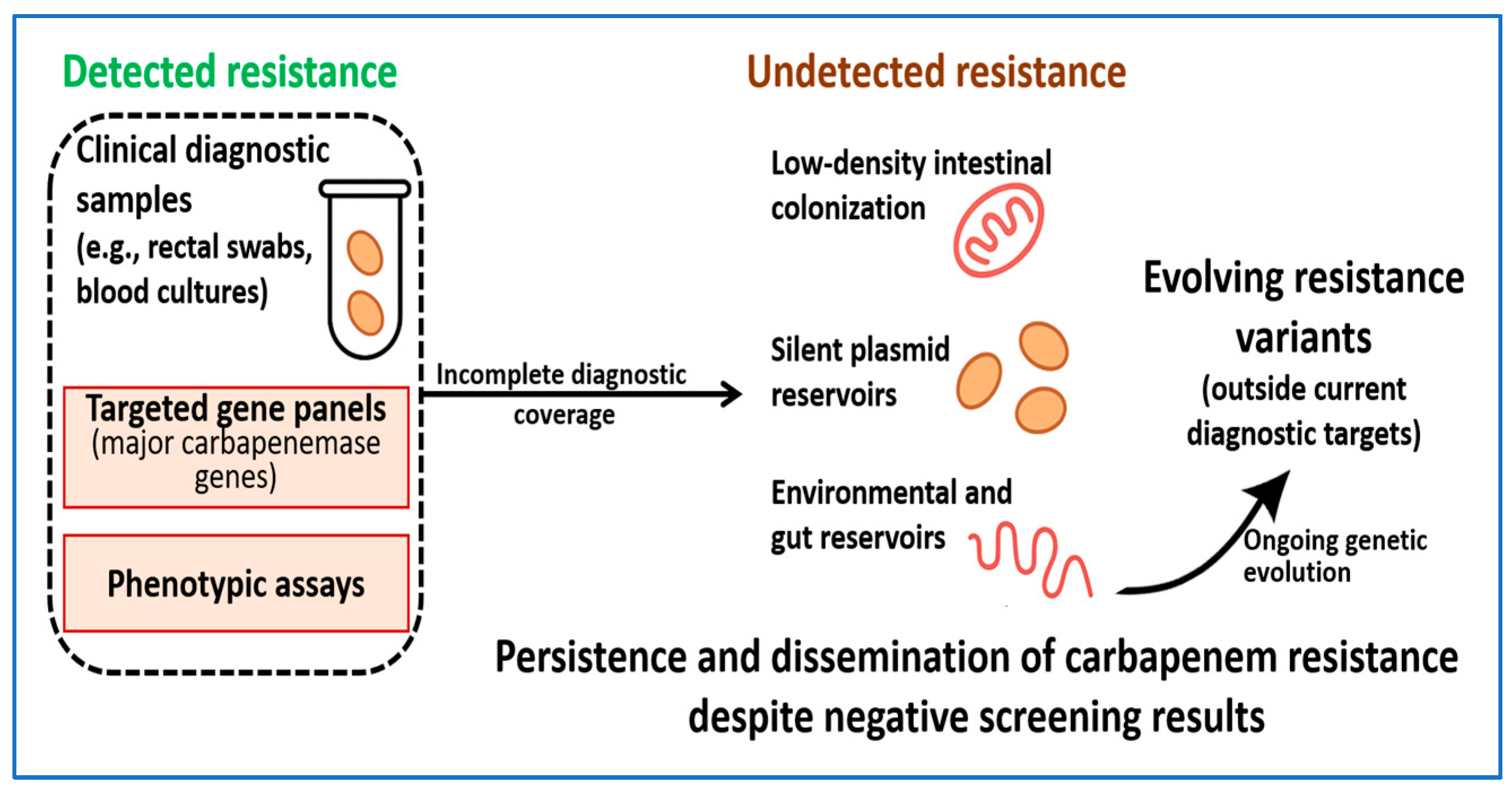

7. Diagnostic Blind Spots and Emerging Challenges

7.1. Silent Carriers and Low-Expression Carbapenemase Genes

7.2. Undetected Plasmid and Environmental Reservoirs

7.3. Evolution Beyond Current Diagnostic Targets

7.4. Implications for Clinical Care and Surveillance

8. From Detection to Disruption: Can Molecular Tools Alter Resistance Routes?

8.1. CRISPR-Based Targeting of Resistance Determinants

8.2. Anti-Plasmid Strategies and Plasmid Curing

8.3. Phage-Assisted Delivery and Phage Therapy

9. Future Perspectives: Toward Integrated Molecular Surveillance and Intervention

9.1. Resistome-Based Surveillance Concepts

9.2. Integration of Diagnostics with Stewardship

9.3. System-Level Intervention Frameworks

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, R.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Qian, K. Containment of a carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in an intensive care unit during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1557068, Correction in Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1650017. [Google Scholar]

- Akturk, H.; Sutcu, M.; Somer, A.; Aydın, D.; Cihan, R.; Ozdemir, A.; Coban, A.; Ince, Z.; Citak, A.; Salman, N. Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae colonization in pediatric and neonatal intensive care units: Risk factors for progression to infection. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 20, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Li, X.; Luo, M.; Xu, X.; Su, K.; Chen, S.; Qing, Y.; Li, Y.; Qiu, J. Risk factors for carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infection: A meta-analysis. Microb. Drug Resist. 2018, 24, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Wang, J.; Yao, Z.; Ma, B.; Li, Y.; Yan, W.; Wang, S.; Ma, Q.; Zhang, J.; Xu, J. Risk factors for carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infections and outcomes. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yuan, X.-D.; Pang, T.; Duan, S.-H. The risk factors of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infection: A Single-Center Chinese Retrospective Study. Infect. Drug Resist. 2022, 2022, 1477–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Xu, J.; Wei, Y.; Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Xue, R. Clinical and molecular characteristics of Klebsiella pneumoniae ventilator-associated pneumonia in mainland China. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.; Jafari, S.; Ghafouri, L.; Ardakani, H.M.; Abdollahi, A.; Beigmohammadi, M.T.; Manshadi, S.A.D.; Feizabadi, M.M.; Ramezani, M.; Abtahi, H. Ventilator-associated pneumonia: Multidrug resistant acinetobacter vs. extended spectrum beta lactamase-producing Klebsiella. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2020, 14, 660–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, C.-H.; Fang, S.-Y.; Chou, C.-H.; Tsai, T.-Y.; Lin, Y.-T. Clinical characteristics of patients with pneumonia caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae in Taiwan and prevalence of antimicrobial-resistant and hypervirulent strains: A retrospective study. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2020, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramadan, R.A.; Bedawy, A.M.; Negm, E.M.; Hassan, T.H.; Ibrahim, D.A.; ElSheikh, S.M.; Amer, R.M. Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae among patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia: Evaluation of antibiotic combinations and susceptibility to new antibiotics. Infect. Drug Resist. 2022, 15, 3537–3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.-W.; Wan, T.-E.; Fu, B.-H.; Yang, G.-H.; Jiang, M.-T.; Pan, J.-S. Global burden of Klebsiella pneumoniae infections and antimicrobial resistance in 2019. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, L.; Li, S.; Guo, J.; Hu, Y.; Pan, L.; Wang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, Q.; Lu, Z.; Kong, X. Global and regional burden of bloodstream infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria in 2019: A systematic analysis from the MICROBE database. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2025, 153, 107769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girmenia, C.; Serrao, A.; Canichella, M. Epidemiology of carbapenem resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infections in mediterranean countries. Mediterr. J. Hematol. Infect. Dis. 2016, 8, e2016032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, H.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Chen, Q.; Li, Y.; Hu, Z.; Feng, X.; Chai, Y.; Dong, Z. Seven-year change of prevalence, clinical risk factors, and mortality of patients with carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infection in a Chinese teaching hospital: A case-case-control study. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1531984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, P.B.; Teo, J.Q.-M.; Fouts, D.E.; Clarke, T.H.; Ruffin, F.; Fowler, V.G., Jr.; Thaden, J.T.; Kwa, A.L.-H. Molecular epidemiology and clinical characteristics of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream and pneumonia isolates. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e00631-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkhair, A.; Al Saadi, K.; Al Adawi, B. Epidemiology and mortality outcome of carbapenem-and colistin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infections. IJID Reg. 2023, 7, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List, 2024: Bacterial Pathogens of Public Health Importance to Guide Research, Development and Strategies to Prevent and Control Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240093461? (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Sati, H.; Carrara, E.; Savoldi, A.; Hansen, P.; Garlasco, J.; Campagnaro, E.; Boccia, S.; Castillo-Polo, J.A.; Magrini, E.; Garcia-Vello, P. The WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List 2024: A prioritisation study to guide research, development, and public health strategies against antimicrobial resistance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antochevis, L.C.; Wilhelm, C.M.; Arns, B.; Sganzerla, D.; Sudbrack, L.O.; Nogueira, T.C.; Guzman, R.D.; Martins, A.S.; Cappa, D.S.; Dos Santos, Â.C. World Health Organization priority antimicrobial resistance in Enterobacterales, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecium healthcare-associated bloodstream infections in Brazil (ASCENSION): A prospective, multicentre, observational study. Lancet Reg. Health–Am. 2025, 43, 101004. [Google Scholar]

- Gürbüz, M.; Gencer, G. Global trends and future directions on carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) research: A comprehensive bibliometric analysis (2020–2024). Medicine 2024, 103, e40783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iovleva, A.; Doi, Y. Carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae. Clin. Lab. Med. 2017, 37, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melinte, V.; Radu, M.A.; Văcăroiu, M.C.; Mîrzan, L.; Holban, T.S.; Ileanu, B.V.; Cismaru, I.M.; Gheorghiță, V. Epidemiology of carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella Pneumoniae Co-Producing MBL and OXA-48-Like in a romanian tertiary hospital: A call to action. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyüktuna, S.A.; Hasbek, M.; Çelik, C.; Ünlüsavuran, M.; Avcı, O.; Baltacı, S.; Fırtına Topcu, K.; Elaldı, N. Klebsiella pneumoniae infections in the intensive care unit: Risk factors related to carbapenem resistance and patient mortality. Mikrobiyoloji Bul. 2020, 54, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, H.; Liu, J.; Yu, J.; Guo, K.; Chen, F.; Yu, J.; Liu, Y. Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae gut colonization and subsequent infection in pediatric intensive care units in shanghai, China. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2025, 24, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Wang, Z.; Han, X.; Hu, H.; Quan, J.; Jiang, Y.; Du, X.; Zhou, Z.; Yu, Y. The correlation between intestinal colonization and infection of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: A systematic review. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 38, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorrie, C.L.; Mirčeta, M.; Wick, R.R.; Edwards, D.J.; Thomson, N.R.; Strugnell, R.A.; Pratt, N.F.; Garlick, J.S.; Watson, K.M.; Pilcher, D.V. Gastrointestinal carriage is a major reservoir of Klebsiella pneumoniae infection in intensive care patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017, 65, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, Q.; Liu, W.-E.; Yan, Q. Risk factors for subsequential carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical infection among rectal carriers with carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 1299–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, R.; Lu, Y.; Wu, X.; Yu, P.; Lan, P.; Wu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Q.; Pi, X.; Liu, W. Anticolonization of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae by Lactobacillus plantarum LP1812 through accumulated acetic acid in mice intestinal. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 804253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, C.; Czauderna, A.; Cheng, L.; Lagune, M.; Jung, H.-J.; Kim, S.G.; Pamer, E.G.; Prados, J.; Chen, L.; Becattini, S. Intestinal carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae undergoes complex transcriptional reprogramming following immune activation. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2340486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, I.; Sudarsanan, D.; Moonah, S. The gut microbiome as a major source of drug-resistant infections: Emerging strategies to decolonize and target the gut reservoir. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1692582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Du, A.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, B.; Tian, Y.; Liu, H.; Cai, L.; Pang, F.; Li, Y. Microbiome-mediated colonization resistance to carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in ICU patients. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistella, E.; Santini, C. Risk factors and outcomes of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infections. Ital. J. Med. 2016, 10, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritsotakis, E.I.; Tsioutis, C.; Roumbelaki, M.; Christidou, A.; Gikas, A. Antibiotic use and the risk of carbapenem-resistant extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae infection in hospitalized patients: Results of a double case–control study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2011, 66, 1383–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitout, J.D.; Nordmann, P.; Poirel, L. Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae, a key pathogen set for global nosocomial dominance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 5873–5884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyres, K.L.; Holt, K.E. Klebsiella pneumoniae as a key trafficker of drug resistance genes from environmental to clinically important bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2018, 45, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, T.A.; Marr, C.M. Hypervirulent klebsiella pneumoniae. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 32, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.Y.; Baek, Y.J.; Kim, J.H.; Seong, H.; Kim, B.; Kim, Y.C.; Yoon, J.G.; Heo, N.; Moon, S.M.; Kim, Y.A. Guidelines for antibacterial treatment of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales infections. Infect. Chemother. 2024, 56, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, J.W.; Mustapha, M.M.; Griffith, M.P.; Evans, D.R.; Ezeonwuka, C.; Pasculle, A.W.; Shutt, K.A.; Sundermann, A.; Ayres, A.M.; Shields, R.K. Evolution of outbreak-causing carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 at a tertiary care hospital over 8 years. MBio 2019, 10, 10-11281128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- On, Y.; Kim, J.W.; Lee, J.; Yoo, J.S. Genomic analysis of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae blood isolates from nationwide surveillance in South Korea. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1562222, Correction in Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1627539. [Google Scholar]

- Cerqueira, G.C.; Earl, A.M.; Ernst, C.M.; Grad, Y.H.; Dekker, J.P.; Feldgarden, M.; Chapman, S.B.; Reis-Cunha, J.L.; Shea, T.P.; Young, S. Multi-institute analysis of carbapenem resistance reveals remarkable diversity, unexplained mechanisms, and limited clonal outbreaks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 1135–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Pilato, V.; Pollini, S.; Miriagou, V.; Rossolini, G.M.; D’Andrea, M.M. Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: The role of plasmids in emergence, dissemination, and evolution of a major clinical challenge. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2024, 22, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Song, K.; Wang, R.; Wang, S.; Chen, H.; Wang, H. Tracking intra-species and inter-genus transmission of KPC through global plasmids mining. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 114351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luterbach, C.L.; Chen, L.; Komarow, L.; Ostrowsky, B.; Kaye, K.S.; Hanson, B.; Arias, C.A.; Desai, S.; Gallagher, J.C.; Novick, E. Transmission of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in US hospitals. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Luca, M.C.; Sørum, V.; Starikova, I.; Kloos, J.; Hülter, N.; Naseer, U.; Johnsen, P.J.; Samuelsen, Ø. Low biological cost of carbapenemase-encoding plasmids following transfer from Klebsiella pneumoniae to Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 72, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boralli, C.M.d.S.; Paganini, J.A.; Meneses, R.S.; Mata, C.P.S.M.d.; Leite, E.M.M.; Schürch, A.C.; Paganelli, F.L.; Willems, R.J.; Camargo, I.L.B.C. Characterization of blaKPC-2 and blaNDM-1 Plasmids of a K. pneumoniae ST11 Outbreak Clone. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckner, M.M.; Saw, H.T.; Osagie, R.N.; McNally, A.; Ricci, V.; Wand, M.E.; Woodford, N.; Ivens, A.; Webber, M.A.; Piddock, L.J. Clinically relevant plasmid-host interactions indicate that transcriptional and not genomic modifications ameliorate fitness costs of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-carrying plasmids. MBio 2018, 9, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtinen, S.; Huisman, J.S.; Bonhoeffer, S. Evolutionary mechanisms that determine which bacterial genes are carried on plasmids. Evol. Lett. 2021, 5, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, J.P.; Brockhurst, M.A.; Dytham, C.; Harrison, E. The evolution of plasmid stability: Are infectious transmission and compensatory evolution competing evolutionary trajectories? Plasmid 2017, 91, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-del Valle, A.; León-Sampedro, R.; Rodríguez-Beltrán, J.; DelaFuente, J.; Hernández-García, M.; Ruiz-Garbajosa, P.; Cantón, R.; Peña-Miller, R.; San Millán, A. Variability of plasmid fitness effects contributes to plasmid persistence in bacterial communities. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Lu, X.; Peng, K.; Chen, S.; He, S.; Li, R. Structural diversity, fitness cost, and stability of a bla NDM-1-bearing cointegrate plasmid in Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nang, S.C.; Morris, F.C.; McDonald, M.J.; Han, M.-L.; Wang, J.; Strugnell, R.A.; Velkov, T.; Li, J. Fitness cost of mcr-1-mediated polymyxin resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 1604–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Liu, N.; Xiao, S.; Yao, L.; Li, J.; Zhuo, C.; He, N. Adaptive evolution compensated for the plasmid fitness costs brought by specific genetic conflicts. Pathogens 2023, 12, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcari, G.; Cecilia, F.; Oliva, A.; Polani, R.; Raponi, G.; Sacco, F.; De Francesco, A.; Pugliese, F.; Carattoli, A. Genotypic evolution of Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 512 during ceftazidime/avibactam, meropenem/vaborbactam, and cefiderocol treatment, Italy. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaborskytė, G.; Hjort, K.; Lytsy, B.; Sandegren, L. Parallel within-host evolution alters virulence factors in an opportunistic Klebsiella pneumoniae during a hospital outbreak. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Fulgueiras, V.; Zapata, Y.; Papa-Ezdra, R.; Ávila, P.; Caiata, L.; Seija, V.; Rodriguez, A.E.R.; Magallanes, C.; Villalba, C.M.; Vignoli, R. First characterization of K. pneumoniae ST11 clinical isolates harboring blaKPC-3 in Latin America. Rev. Argent. De Microbiol. 2020, 52, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jousset, A.B.; Rosinski-Chupin, I.; Takissian, J.; Glaser, P.; Bonnin, R.A.; Naas, T. Transcriptional landscape of a bla KPC-2 plasmid and response to imipenem exposure in Escherichia coli TOP10. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagiannitsis, C.C.; Di Pilato, V.; Giani, T.; Giakkoupi, P.; Riccobono, E.; Landini, G.; Miriagou, V.; Vatopoulos, A.C.; Rossolini, G.M. Characterization of KPC-encoding plasmids from two endemic settings, Greece and Italy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 2824–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Simmonds, A.; Annavajhala, M.K.; Tang, N.; Rozenberg, F.D.; Ahmad, M.; Park, H.; Lopatkin, A.J.; Uhlemann, A.C. Population structure of bla KPC-harbouring IncN plasmids at a New York City medical centre and evidence for multi-species horizontal transmission. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2022, 77, 1873–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, J.A.; Melano, R.; Cárdenas, P.A.; Trueba, G. Mobile genetic elements associated with carbapenemase genes in South American Enterobacterales. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 24, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, S.R.; Ginn, A.N.; Wiklendt, A.M.; Ellem, J.; Wong, J.S.; Ingram, P.; Guy, S.; Garner, S.; Iredell, J.R. Emergence of blaKPC carbapenemase genes in Australia. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2015, 45, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doumith, M.; Findlay, J.; Hirani, H.; Hopkins, K.; Livermore, D.; Dodgson, A.; Woodford, N. Major role of pKpQIL-like plasmids in the early dissemination of KPC-type carbapenemases in the UK. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 2241–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghamohammad, S.; Khazani Asforooshani, M.; Malek Mohammadi, Y.; Sholeh, M.; Badmasti, F. Decoding the genetic structure of conjugative plasmids in international clones of Klebsiella pneumoniae: A deep dive into bla KPC, bla NDM, bla OXA-48, and bla GES genes. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0292288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Dong, F.; Dai, P.; Xu, M.; Yu, L.; Hu, D.; Feng, J.; Zhang, J.; Jing, Y. Coexistence of blaKPC-2 and blaNDM-1 in one IncHI5 plasmid confers transferable carbapenem resistance from a clinical isolate of Klebsiella michiganensis in China. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2023, 35, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, S.; Cohen, V.; Reuter, S.; Sheppard, A.E.; Giani, T.; Parkhill, J.; the European Survey of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae (EuSCAPE) Working Group; the ESCMID Study Group for Epidemiological Markers (ESGEM); Rossolini, G.M.; Feil, E.J. Integrated chromosomal and plasmid sequence analyses reveal diverse modes of carbapenemase gene spread among Klebsiella pneumoniae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 25043–25054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, T.; Yu, Z.; Qin, S.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y. Identification of an IncHI5-like plasmid co-harboring bla NDM− 1 and bla OXA− 1 in mcr-8.1-positive Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1601035. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, L.; Yang, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, K.; Yin, B.; Yang, X.; Ye, H.; Lou, Z.; Hu, T.; Zhu, W. Emergence of ST11 Klebsiella pneumoniae co-carrying bla KPC-2 and bla IMP-8 on conjugative plasmids. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e03345-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, L.; Shen, Y.; Chen, R.; Li, C.; Liu, R.; Jia, Y.; Qi, S.; Guo, X. The characterization of an IncN-IncR fusion plasmid co-harboring bla TEM−40, bla KPC−2, and bla IMP−4 derived from ST1393 Klebsiella pneumoniae. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veloso, M.; Acosta, J.; Arros, P.; Berríos-Pastén, C.; Rojas, R.; Varas, M.; Allende, M.L.; Chávez, F.P.; Araya, P.; Hormazábal, J.C. Population genomics, resistance, pathogenic potential, and mobile genetic elements of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae causing infections in Chile. bioRxiv 2022, 2022-11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnning, A.; Karami, N.; Tång Hallbäck, E.; Müller, V.; Nyberg, L.; Buongermino Pereira, M.; Stewart, C.; Ambjörnsson, T.; Westerlund, F.; Adlerberth, I. The resistomes of six carbapenem-resistant pathogens—A critical genotype–phenotype analysis. Microb. Genom. 2018, 4, e000233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Palacios, P.; Delgado-Valverde, M.; Gual-de-Torrella, A.; Oteo-Iglesias, J.; Pascual, Á.; Fernández-Cuenca, F. Co-transfer of plasmid-encoded bla carbapenemases genes and mercury resistance operon in high-risk clones of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 9231–9242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Håkonsholm, F.; Hetland, M.A.; Löhr, I.H.; Lunestad, B.T.; Marathe, N.P. Co-localization of clinically relevant antibiotic-and heavy metal resistance genes on plasmids in Klebsiella pneumoniae from marine bivalves. MicrobiologyOpen 2023, 12, e1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engobo, G.P.; Su, W.; Wang, S.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Geng, X.; Xu, H.; Li, L.; Wang, M. Prevalent and diverse new plasmid-encoded heavy metal and antimicrobial resistance in Klebsiella strains isolated from hospital wastewater. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1653886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Li, X.; Li, L.; Li, S.; Liao, X.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y. Co-spread of metal and antibiotic resistance within ST3-IncHI2 plasmids from E. coli isolates of food-producing animals. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partridge, S.R.; Kwong, S.M.; Firth, N.; Jensen, S.O. Mobile genetic elements associated with antimicrobial resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 31, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolhouse, M.; Ward, M.; Van Bunnik, B.; Farrar, J. Antimicrobial resistance in humans, livestock and the wider environment. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 370, 20140083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Zhou, J.; Yu, L.; Shao, L.; Cai, S.; Hu, H.; Shi, Q.; Wang, Z.; Hua, X.; Jiang, Y. Genome sequencing unveils bla KPC-2-harboring plasmids as drivers of enhanced resistance and virulence in nosocomial Klebsiella pneumoniae. MSystems 2024, 9, e00924-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloso, M.; Arros, P.; Acosta, J.; Rojas, R.; Berríos-Pastén, C.; Varas, M.; Araya, P.; Hormazábal, J.C.; Allende, M.L.; Chávez, F.P. Antimicrobial resistance, pathogenic potential, and genomic features of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated in Chile: High-risk ST25 clones and novel mobile elements. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e00399-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, D.; Dong, N.; Zheng, Z.; Lin, D.; Huang, M.; Wang, L.; Chan, E.W.-C.; Shu, L.; Yu, J.; Zhang, R. A fatal outbreak of ST11 carbapenem-resistant hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Chinese hospital: A molecular epidemiological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N.; Zhang, R.; Liu, L.; Li, R.; Lin, D.; Chan, E.W.-C.; Chen, S. Genome analysis of clinical multilocus sequence Type 11 Klebsiella pneumoniae from China. Microb. Genom. 2018, 4, e000149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.M.; Wyres, K.L.; Judd, L.M.; Wick, R.R.; Jenney, A.; Brisse, S.; Holt, K.E. Tracking key virulence loci encoding aerobactin and salmochelin siderophore synthesis in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Genome Med. 2018, 10, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.A.E.-G.E.-S.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yan, B.; Chen, G.; Hassan, R.M.; Zhong, L.-L.; Chen, Y.; Roberts, A.P.; Wu, Y. Emergence of hypervirulent carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae coharboring a bla NDM-1-carrying virulent plasmid and a bla KPC-2-carrying plasmid in an Egyptian hospital. Msphere 2021, 6, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shon, A.S.; Bajwa, R.P.; Russo, T.A. Hypervirulent (hypermucoviscous) Klebsiella pneumoniae: A new and dangerous breed. Virulence 2013, 4, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Liao, X. Hypervirulent klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect. Drug Resist. 2023, 16, 5243–5249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shi, Y.; Song, X.; Yin, X.; Liu, H. Mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in Klebsiella: Advances in detection methods and clinical implications. Infect. Drug Resist. 2025, 18, 1339–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, T.-y.; Liao, B.-b.; Yang, L.-R.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.-b. Hypervirulent and carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: A global public health threat. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 288, 127839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalakar, S.; Rameshkumar, M.R.; Jyothi, T.L.; Sundaramurthy, R.; Senthamilselvan, B.; Nishanth, A.; Krithika, C.; Alodaini, H.A.; Hatamleh, A.A.; Arunagirinathan, N. Molecular detection of blaNDM and blaOXA-48 genes in Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from a tertiary care hospital. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 2024, 36, 103233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Dong, N.; Chan, E.W.-C.; Zhang, R.; Chen, S. Carbapenem resistance-encoding and virulence-encoding conjugative plasmids in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Trends Microbiol. 2021, 29, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valério de Lima, A.; Lima, K.d.O.; Cappellano, P.; Cifuentes, S.; Lincopan, N.; Sampaio, S.C.F.; Sampaio, J.L.M. Evaluation of the KPC/IMP/NDM/VIM/OXA-48 Combo Test Kit and Carbapenem-Resistant KNIVO Detection K-Set in detecting KPC variants. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2024, 62, e01123-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, Z.; Gu, D.; Zhou, H.; Dong, N.; Cai, C.; Chen, G.; Zhang, R. Effectiveness of antimicrobial agent combinations against carbapenem-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae with KPC variants in China. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1519319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simo, G.G.; Mefo’o, J.P.N.; Temfemo, A.; Ngondi, G.; Ebongue, C.O.; Ngaba, G.P.; Mengue, E.R.; Njoya, A.A.P.; Patient, M.E.J.; Adiogo, D. Detection of the Production of KPC, NDM, OXA-48, VIM and IMP-Type Carbapenemases by Gram-Negative Bacilli in Resource-Limited Setting. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2024, 13, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, E.; Saavedra, M.J.; Costa, E.; de Lencastre, H.; Poirel, L.; Aires-de-Sousa, M. Epidemiology of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in northern Portugal: Predominance of KPC-2 and OXA-48. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 22, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, D.S.; Nica, M.; Dascalu, A.; Oprisan, C.; Albu, O.; Codreanu, D.R.; Kosa, A.G.; Popescu, C.P.; Florescu, S.A. Carbapenem-Resistant NDM and OXA-48-like Producing K. pneumoniae: From Menacing Superbug to a Mundane Bacteria; A Retrospective Study in a Romanian Tertiary Hospital. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zowawi, H.M.; Sartor, A.L.; Balkhy, H.H.; Walsh, T.R.; Al Johani, S.M.; AlJindan, R.Y.; Alfaresi, M.; Ibrahim, E.; Al-Jardani, A.; Al-Abri, S. Molecular characterization of carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in the countries of the Gulf cooperation council: Dominance of OXA-48 and NDM producers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 3085–3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, M.; Mojtahedi, A.; Mahdieh, N.; Jafari, A.; Arya, M.J. High Prevalence of bla OXA-48 and bla NDM-Producing Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolated from Clinical Samples in Shahid Rajaei Hospital in Tehran, Iran. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 2022, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Mohamed, A.M.; Faiz, A.; Ahmad, J. Enterobacterial infection in Saudi Arabia: First record of Klebsiella pneumoniae with triple carbapenemase genes resistance. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2019, 13, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takei, S.; Tabe, Y.; Miida, T.; Hishinuma, T.; Khasawneh, A.; Kirikae, T.; Sherchand, J.B.; Tada, T. Multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates producing NDM-and OXA-type carbapenemase in Nepal. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 37, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muneer, F.; Raj, N.; Das, A.; Singh, V.; Sen, M.; Agarwal, J. The Rising Menace: Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Tertiary Care Center and Co-dominance of blaNDM, blaOXA-48 Along With the Emergence of blaVIM. Cureus 2025, 17, e94303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.-K.; Fung, C.-P.; Lin, J.-C.; Chen, J.-H.; Chang, F.-Y.; Chen, T.-L.; Siu, L.K. Klebsiella pneumoniae outer membrane porins OmpK35 and OmpK36 play roles in both antimicrobial resistance and virulence. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 1485–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, H.G.; Perera, S.R.; Tremblay, Y.D.; Thomassin, J.-L. Antimicrobial resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae: An overview of common mechanisms and a current Canadian perspective. Can. J. Microbiol. 2024, 70, 507–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamzaoui, Z.; Ocampo-Sosa, A.; Martinez, M.F.; Landolsi, S.; Ferjani, S.; Maamar, E.; Saidani, M.; Slim, A.; Martinez-Martinez, L.; Boubaker, I.B.-B. Role of association of OmpK35 and OmpK36 alteration and blaESBL and/or blaAmpC genes in conferring carbapenem resistance among non-carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2018, 52, 898–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalmolin, T.V.; Bianchini, B.V.; Rossi, G.G.; Ramos, A.C.; Gales, A.C.; de Arruda Trindade, P.; de Campos, M.M.A. Detection and analysis of different interactions between resistance mechanisms and carbapenems in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2017, 48, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Din, A.A.M.N.; Harfoush, R.A.H.; Okasha, H.A.S.; Kholeif, D.A.E.S. Study of OmpK35 and OmpK36 expression in carbapenem resistant ESBL producing clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Adv. Microbiol. 2016, 6, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejaz, H. Analysis of diverse β-lactamases presenting high-level resistance in association with OmpK35 and OmpK36 porins in ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 29, 3440–3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, S.; Wong, J.L.; Sanchez-Garrido, J.; Kwong, H.-S.; Low, W.W.; Morecchiato, F.; Giani, T.; Rossolini, G.M.; Brett, S.J.; Clements, A. Widespread emergence of OmpK36 loop 3 insertions among multidrug-resistant clones of Klebsiella pneumoniae. PLoS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010334. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, J.L.; Romano, M.; Kerry, L.E.; Kwong, H.-S.; Low, W.-W.; Brett, S.J.; Clements, A.; Beis, K.; Frankel, G. OmpK36-mediated Carbapenem resistance attenuates ST258 Klebsiella pneumoniae in vivo. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3957, Correction in Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Meekes, L.M.; Heikema, A.P.; Tompa, M.; Astorga Alsina, A.L.; Hiltemann, S.D.; Stubbs, A.P.; Dekker, L.J.; Foudraine, D.E.; Strepis, N.; Pitout, J.D. Proteogenomic analysis demonstrates increased bla OXA-48 copy numbers and OmpK36 loss as contributors to carbapenem resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2025, 69, e00107-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.-K.; Liou, C.-H.; Fung, C.-P.; Lin, J.-C.; Siu, L.K. Single or in combination antimicrobial resistance mechanisms of Klebsiella pneumoniae contribute to varied susceptibility to different carbapenems. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allander, L.; Vickberg, K.; Fermér, E.; Söderhäll, T.; Sandegren, L.; Lagerbäck, P.; Tängdén, T. Impact of porin deficiency on the synergistic potential of colistin in combination with β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors against ESBL-and carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2024, 68, e00762-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, E.; Llobet, E.; Doménech-Sánchez, A.; Martínez-Martínez, L.; Bengoechea, J.A.; Albertí, S. Klebsiella pneumoniae AcrAB efflux pump contributes to antimicrobial resistance and virulence. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetri, S.; Bhowmik, D.; Paul, D.; Pandey, P.; Chanda, D.D.; Chakravarty, A.; Bora, D.; Bhattacharjee, A. AcrAB-TolC efflux pump system plays a role in carbapenem non-susceptibility in Escherichia coli. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Yeshwante, S.; Bui, N.M.; Carbone, V.; Hicks, L.; Blough, B.E.; Velkov, T.; Rao, G.G. A novel role for colistin as an efflux pump inhibitor in multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 34612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhogal, K.; Clough, B.; Emmerson, C.; Organ, A.; Chen, Y.; Buckner, M.M.; Alav, I. Strain-dependent contribution of the AcrAB-TolC efflux pump to Klebsiella pneumoniae physiology. Microbiol. (Read.) 2025, 171, 001647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussein, R.A.; Al-Kubaisy, S.H.; Al-Ouqaili, M.T. The influence of efflux pump, outer membrane permeability and β-lactamase production on the resistance profile of multi, extensively and pandrug resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Infect. Public Health 2024, 17, 102544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, N.; Muhammad, A.; Abozait, H. Antibiotic Resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae in Iraq: A Narrative Review. J. Life Bio Sci. Res. 2025, 6, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S.; Mirnejad, R.; Babapour, E. Involvement of AcrAB and OqxAB efflux pumps in antimicrobial resistance of clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumonia. J. Appl. Biotechnol. Rep. 2020, 7, 251–257. [Google Scholar]

- Huy, T.X.N. Overcoming Klebsiella pneumoniae antibiotic resistance: New insights into mechanisms and drug discovery. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2024, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vornhagen, J.; Rao, K.; Bachman, M.A. Gut community structure as a risk factor for infection in Klebsiella pneumoniae-colonized patients. Msystems 2024, 9, e00786-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diebold, P.J.; Rhee, M.W.; Shi, Q.; Trung, N.V.; Umrani, F.; Ahmed, S.; Kulkarni, V.; Deshpande, P.; Alexander, M.; Thi Hoa, N. Clinically relevant antibiotic resistance genes are linked to a limited set of taxa within gut microbiome worldwide. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woelfel, S.; Silva, M.S.; Stecher, B. Intestinal colonization resistance in the context of environmental, host, and microbial determinants. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 820–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tascini, C.; Lipsky, B.; Iacopi, E.; Ripoli, A.; Sbrana, F.; Coppelli, A.; Goretti, C.; Piaggesi, A.; Menichetti, F. KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae rectal colonization is a risk factor for mortality in patients with diabetic foot infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015, 21, 790.e791–790.e793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Madueno, E.I.; Moradi, M.; Eddoubaji, Y.; Shahi, F.; Moradi, S.; Bernasconi, O.J.; Moser, A.I.; Endimiani, A. Intestinal colonization with multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales: Screening, epidemiology, clinical impact, and strategies to decolonize carriers. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2023, 42, 229–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Maio, F.; Bianco, D.M.; Santarelli, G.; Rosato, R.; Monzo, F.R.; Fiori, B.; Sanguinetti, M.; Posteraro, B. Profiling the gut microbiota to assess infection risk in Klebsiella pneumoniae-colonized patients. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2468358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Guern, R.; Stabler, S.; Gosset, P.; Pichavant, M.; Grandjean, T.; Faure, E.; Karaca, Y.; Faure, K.; Kipnis, E.; Dessein, R. Colonization resistance against multi-drug-resistant bacteria: A narrative review. J. Hosp. Infect. 2021, 118, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.; Kim, B.-S.; Suk, K.T.; Lee, S.S. Gut Microbiome-Based Strategies for the Control of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 35, e2406017, Correction in J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 35, e35005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindi, A.A.; Alsayed, S.M.; Abushoshah, I.; Bokhary, D.H.; Tashkandy, N.R. Profile of the gut microbiome containing carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in ICU patients. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, Z.; Ding, W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Wu, L.; Xu, X.; Gao, Y.; Jiang, R. Gut microbiota dysbiosis and systemic immune dysfunction in critical ill patients with multidrug-resistant bacterial colonization and infection. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, C.K.; Kashaf, S.S.; Stacy, A.; Proctor, D.M.; Almeida, A.; Bouladoux, N.; Chen, M.; Program, N.C.S.; Finn, R.D.; Belkaid, Y. A mouse model of occult intestinal colonization demonstrating antibiotic-induced outgrowth of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Microbiome 2022, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flury, B.B.; Andrey, D.; Kohler, P. Antibiotics’ collateral effects on the gut microbiota in the selection of ESKAPE pathogens. CMI Commun. 2024, 1, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, G.J.; Domingues, S. Insights on the horizontal gene transfer of carbapenemase determinants in the opportunistic pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii. Microorganisms 2016, 4, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huddleston, J.R. Horizontal gene transfer in the human gastrointestinal tract: Potential spread of antibiotic resistance genes. Infect. Drug Resist. 2014, 7, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chan, E.W.-C.; Chen, S. Transmission and stable inheritance of carbapenemase gene (blaKPC-2 or blaNDM-1)-encoding and mcr-1-encoding plasmids in clinical Enterobacteriaceae strains. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 26, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardiman, C.; Weingarten, R.; Conlan, S.; Khil, P.; Dekker, J.; Mathers, A.; Sheppard, A.; Segre, J.; Frank, K. Horizontal transfer of carbapenemase-encoding plasmids and comparison with hospital epidemiology data. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 4910–4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamar, M.U.; Sierra, R.; Jabeen, K.; Rizwan, M.; Rashid, A.; Dar, Y.F.; Andrey, D.O. Genomic characterization of plasmids harboring bla NDM-1, bla NDM-5, and bla NDM-7 carbapenemase alleles in clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae in Pakistan. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, e02359-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Sampedro, R.; DelaFuente, J.; Díaz-Agero, C.; Crellen, T.; Musicha, P.; Rodríguez-Beltrán, J.; de la Vega, C.; Hernández-García, M.; Group, R.-G.W.S.; López-Fresneña, N. Pervasive transmission of a carbapenem resistance plasmid in the gut microbiota of hospitalized patients. Nat. Microbiol. 2021, 6, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevan, E.; Powell, M.J.; Toleman, M.A.; Thomas, C.; Piddock, L.; Hawkey, P. Molecular characterization of plasmids encoding blaCTX-M from faecal Escherichia coli in travellers returning to the UK from South Asia. J. Hosp. Infect. 2021, 114, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakari, D.A.; Eneye, B.K.; Idris, E.T.; Anoze, A.A.; Moyosore, A.A.; Boniface, M.T.; Mustapha, I.O.; Bashir, A.; Okpanachi, M.; Amoka, A. The human microbiome as a reservoir and modulator of antimicrobial resistance: Emerging therapeutic implications. Microbes Infect. Dis. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusumano, G.; Flores, G.A.; Venanzoni, R.; Angelini, P. The Impact of Antibiotic Therapy on Intestinal Microbiota: Dysbiosis, Antibiotic Resistance, and Restoration Strategies. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guinan, J.; Wang, S.; Hazbun, T.R.; Yadav, H.; Thangamani, S. Antibiotic-induced decreases in the levels of microbial-derived short-chain fatty acids correlate with increased gastrointestinal colonization of Candida albicans. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishna, B.S.; Patankar, R. Antibiotic-associated Gut Dysbiosis. J. Assoc. Physicians India 2023, 71, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.C.-H.; Shih, Y.-A.; Wu, L.-L.; Lin, Y.-D.; Kuo, W.-T.; Peng, W.-H.; Lu, K.-S.; Wei, S.-C.; Turner, J.R.; Ni, Y.-H. Enteric dysbiosis promotes antibiotic-resistant bacterial infection: Systemic dissemination of resistant and commensal bacteria through epithelial transcytosis. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2014, 307, G824–G835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukili, N.H.; Perrin, A.; Gaillot, O.; Bruandet, A.; Boudis, F.; Sendid, B.; Nseir, S.; Zahar, J.-R. Is intestinal colonization with multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales associated with higher rates of nosocomial Enterobacterales bloodstream infections? Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2025, 150, 107274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, D.; Freeman, R.; Hopkins, K.; Hopkins, S.; Woodford, N.; Brown, C.; Chilton, C.; Davies, F.; Davies, K.; Lewis, T. Commercial Assays for the Detection of Acquired Carbapenemases; Public Health England: Lond, UK, 2019.

- Lee, T.D.; Adie, K.; McNabb, A.; Purych, D.; Mannan, K.; Azana, R.; Ng, C.; Tang, P.; Hoang, L.M. Rapid detection of KPC, NDM, and OXA-48-like carbapenemases by real-time PCR from rectal swab surveillance samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 2731–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, K.; Boutin, S.; Bandilla, M.; Heeg, K.; Dalpke, A.H. Fast and automated detection of common carbapenemase genes using multiplex real-time PCR on the BD MAX™ system. J. Microbiol. Methods 2021, 185, 106224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duze, S.T.; Thomas, T.; Pelego, T.; Jallow, S.; Perovic, O.; Duse, A. Evaluation of Xpert Carba-R for detecting carbapenemase-producing organisms in South Africa. Afr. J. Lab. Med. 2023, 12, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovacchini, N.; Chilleri, C.; Baccani, I.; Riccobono, E.; Rossolini, G.M.; Antonelli, A. Evaluation of Xpert® Carba-R Assay Performance from FecalSwab™ Samples. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Hao, Y.; Shao, C.; Wang, Y.; Jin, Y. Accuracy of Xpert Carba-R assay for the diagnosis of carbapenemase-producing organisms from rectal swabs and clinical isolates: A meta-analysis of diagnostic studies. J. Mol. Diagn. 2021, 23, 1534–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cury, A.P.; Junior, J.A.; Costa, S.F.; Salomão, M.C.; Boszczowski, Í.; Duarte, A.J.; Rossi, F. Diagnostic performance of the Xpert Carba-R™ assay directly from rectal swabs for active surveillance of carbapenemase-producing organisms in the largest Brazilian University Hospital. J. Microbiol. Methods 2020, 171, 105884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keidar-Friedman, D.; Gil, L.; Tsur, A.; Brosh-Nissimov, T.; Carmeli, Y.; Rosenfeld, B.D.; Sorek, N. Evaluation of sample pooling using Xpert Carba-R and Xpert vanA/vanB PCR for screening of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus colonization. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e01080-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirier, A.C.; Kuang, D.; Siedler, B.S.; Borah, K.; Mehat, J.W.; Liu, J.; Tai, C.; Wang, X.; van Vliet, A.H.; Ma, W. Development of loop-mediated isothermal amplification rapid diagnostic assays for the detection of Klebsiella pneumoniae and carbapenemase genes in clinical samples. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 8, 794961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, W.; Niu, S.; Chang, Y.; Jia, X.; Huang, S.; Yang, P. Design of rapid detection system for five major carbapenemase families (bla KPC, bla NDM, bla VIM, bla IMP and bla OXA-48-Like) by colorimetric loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 1865–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikita, K.; Tajima, M.; Haque, A.; Kato, Y.; Iwata, S.; Suzuki, K.; Hasegawa, N.; Yano, H.; Matsumoto, T. Development of a Simple Method to Detect the Carbapenemase-Producing Genes bla NDM, bla OXA-48-like, bla IMP, bla KPC, and bla VIM Using a LAMP Method with Lateral Flow DNA Chromatography. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakano, R.; Nakano, A.; Ishii, Y.; Ubagai, T.; Kikuchi-Ueda, T.; Kikuchi, H.; Tansho-Nagakawa, S.; Kamoshida, G.; Mu, X.; Ono, Y. Rapid detection of the Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) gene by loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP). J. Infect. Chemother. 2015, 21, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, N.; Li, G.; Si, Y.; Zhang, W.; Ye, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, K.; Zong, M.; Fan, L. Evaluation of LAMP assay using phenotypic tests and PCR for detection of bla KPC gene among clinical samples. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2022, 36, e24310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.H.; Hassan, E.A.; Hassan, M.A.; Reda, A.; Elghazaly, S.M.; Mohammed, S.M. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay versus polymerase chain reaction for detection of blaNDM-1 and blaKPC genes among Gram negative isolates. Microbes Infect. Dis. 2024, 5, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Ye, Z.; Liang, P.; Sun, K.; Kang, W.; Tang, Q.; Yu, X. Mitigating Antibiotic Resistance: The Utilization of CRISPR Technology in Detection. Biosensors 2024, 14, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, H.; Yan, C.; Feng, J.; Gan, L.; Cui, J.; Liu, S.; Zhang, R.; Du, S. A recombinase aided amplification assay for rapid detection of the Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase gene and its characteristics in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 746325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, M.; Xiao, B.; Chen, L.; Huang, X.; Li, J.; Kuang, Z.; Chen, X.; Huang, X.; Sun, Z.; Li, L. Rapid Detection of bla KPC in Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales Based on CRISPR/Cas13a. Curr. Microbiol. 2023, 80, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Lin, C.; Tang, H.; Li, R.; Xia, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Shen, J. A method for detecting five carbapenemases in bacteria based on CRISPR-Cas12a multiple RPA rapid detection technology. Infect. Drug Resist. 2024, 2024, 1599–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simner, P.J.; Pitout, J.D.; Dingle, T.C. Laboratory detection of carbapenemases among Gram-negative organisms. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2024, 37, e00054-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Zahrani, I.A. Routine detection of carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacilli in clinical laboratories: A review of current challenges. Saudi Med. J. 2018, 39, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, L.; Chen, H.; Li, N.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Liang, W. Rapid detection of bla KPC, bla NDM, bla OXA-48-like and bla IMP carbapenemases in enterobacterales using recombinase polymerase amplification combined with lateral flow strip. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 772966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srisrattakarn, A.; Lulitanond, A.; Wilailuckana, C.; Charoensri, N.; Wonglakorn, L.; Saenjamla, P.; Chaimanee, P.; Daduang, J.; Chanawong, A. Rapid and simple identification of carbapenemase genes, bla NDM, bla OXA-48, bla VIM, bla IMP-14 and bla KPC groups, in Gram-negative bacilli by in-house loop-mediated isothermal amplification with hydroxynaphthol blue dye. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 33, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Tian, Y.; Huang, J.; Xu, L.; Fan, Z.; Pan, Z.; Chen, S.; Gao, Y.; Wei, L.; Zheng, S. CRISPR/Cas13-assisted carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae detection. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2024, 57, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Wu, Y.; Liu, M.; Yan, J.; Wei, L. Cas12a/Guide RNA-Based Platform for Rapidly and Accurately Detecting blaKPC Gene in Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales. Infect. Drug Resist. 2024, 17, 2451–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, S.; Siji, A.; Mallur, D.; Kruthika, B.; Gheewalla, N.; Karve, S.; Kavathekar, M.; Tarai, B.; Naik, M.; Hegde, V. PathCrisp: An innovative molecular diagnostic tool for early detection of NDM-resistant infections. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutgring, J.D.; Limbago, B.M. The problem of carbapenemase-producing-carbapenem-resistant-Enterobacteriaceae detection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2016, 54, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliskan-Aydogan, O.; Alocilja, E.C. A review of carbapenem resistance in Enterobacterales and its detection techniques. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsakakis, K.; Kaman, W.E.; Elshout, G.; Specht, M.; Hays, J.P. Challenges in identifying antibiotic resistance targets for point-of-care diagnostics in general practice. Future Microbiol. 2018, 13, 1157–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhang, B.; Yin, W.; Xia, L.; Suo, Y.; Cai, G.; Liu, Y.; Jin, W.; Zhao, Q.; Mu, Y. Enzymatic Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing with Bacteria Identification in 30 min. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 16426–16432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhao, Q.; Cai, G.; Zhang, B.; Suo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jin, W.; Mu, Y. All-In-One Escherichia coli viability assay for multi-dimensional detection of uncomplicated urinary tract infections. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 17853–17860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffs, M.A.; Bhat, S.; Liu, J.L.; Gray, R.A.; Li, X.X.; Sheth, P.M.; Lohans, C.T. Rapid Detection of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacterales Using a Luminescent Whole-Cell Biosensor. ACS Infect. Dis. 2026, 12, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindiyeh, M.; Smollan, G.; Grossman, Z.; Ram, D.; Robinov, J.; Belausov, N.; Ben-David, D.; Tal, I.; Davidson, Y.; Shamiss, A. Rapid detection of bla KPC carbapenemase genes by internally controlled real-time PCR assay using bactec blood culture bottles. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 2480–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chavda, K.D.; Mediavilla, J.R.; Zhao, Y.; Fraimow, H.S.; Jenkins, S.G.; Levi, M.H.; Hong, T.; Rojtman, A.D.; Ginocchio, C.C. Multiplex real-time PCR for detection of an epidemic KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 clone. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 3444–3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Zhang, H.; Wu, S.; Qin, X.; Jia, P.; Tenover, F.C.; Tang, Y.-W.; Li, M.; Hu, F.; Yang, Q. Multicenter evaluation of Xpert Carba-R assay for detection and identification of the carbapenemase genes in rectal swabs and clinical isolates. J. Mol. Diagn. 2021, 23, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.-S.; Yang, N.; Kim, Y.; Lee, M.; Park, S. Performance of Xpert Carba-R Assay for Identification of Carbapenemase Gene in the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory. Ewha Med. J. 2020, 43, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viau, R.; Frank, K.M.; Jacobs, M.R.; Wilson, B.; Kaye, K.; Donskey, C.J.; Perez, F.; Endimiani, A.; Bonomo, R.A. Intestinal carriage of carbapenemase-producing organisms: Current status of surveillance methods. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2016, 29, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowman, W.; Marais, M.; Ahmed, K.; Marcus, L. Routine active surveillance for carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae from rectal swabs: Diagnostic implications of multiplex polymerase chain reaction. J. Hosp. Infect. 2014, 88, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Mangold, K.A.; Wyant, K.; Schora, D.M.; Voss, B.; Kaul, K.L.; Hayden, M.K.; Chundi, V.; Peterson, L.R. Rectal screening for Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases: Comparison of real-time PCR and culture using two selective screening agar plates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 2596–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giani, T.; Tascini, C.; Arena, F.; Ciullo, I.; Conte, V.; Leonildi, A.; Menichetti, F.; Rossolini, G.M. Rapid detection of intestinal carriage of Klebsiella pneumoniae producing KPC carbapenemase during an outbreak. J. Hosp. Infect. 2012, 81, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corso, A.; Pasteran, F.; Marchetti, P.; Appendino, A.; Pereda, R.; Menocal, A.; Sangoy, A.; Kuzawka, M.; Tocho, E.; Cioffi, A. P-2085. Optimizing GAIHN-AR Network Microbiology Laboratory Assets for Early Detection of Carbapenemase-Producing Organisms in Limited Resources Settings: Argentine Experience. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2025, 12, ofae631-2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solgi, H.; Badmasti, F.; Aminzadeh, Z.; Giske, C.; Pourahmad, M.; Vaziri, F.; Havaei, S.; Shahcheraghi, F. Molecular characterization of intestinal carriage of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae among inpatients at two Iranian university hospitals: First report of co-production of bla NDM-7 and bla OXA-48. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 36, 2127–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingarten, R.A.; Johnson, R.C.; Conlan, S.; Ramsburg, A.M.; Dekker, J.P.; Lau, A.F.; Khil, P.; Odom, R.T.; Deming, C.; Park, M. Genomic analysis of hospital plumbing reveals diverse reservoir of bacterial plasmids conferring carbapenem resistance. MBio 2018, 9, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laço, J.; Martorell, S.; Gallegos, M.d.C.; Gomila, M. Yearlong analysis of bacterial diversity in hospital sink drains: Culturomics, antibiotic resistance and implications for infection control. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1501170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamal, A.; Mataseje, L.; Brown, K.; Katz, K.; Johnstone, J.; Muller, M.; Allen, V.; Borgia, S.; Boyd, D.; Ciccotelli, W. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales in hospital drains in Southern Ontario, Canada. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 106, 820–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranega-Bou, P.; Ellaby, N.; Ellington, M.J.; Moore, G. Migration of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC)-producing Enterobacter cloacae through wastewater pipework and establishment in hospital sink waste traps in a laboratory model system. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECDC. Rapid Risk Assessment: Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales—Third Update; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2025. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/risk-assessment-carbapenem-resistant-enterobacterales-third-update-february-2025_0.pdf? (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Apanga, P.A.; Ahmed, J.; Tanner, W.; Starcevich, K.; VanDerslice, J.A.; Rehman, U.; Channa, N.; Benson, S.; Garn, J.V. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in sink drains of 40 healthcare facilities in Sindh, Pakistan: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Berglund, B.; Li, Q.; Shangguan, X.; Li, J.; Liu, F.; Yao, F.; Li, X. Transmission of clones of carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli between a hospital and an urban wastewater treatment plant. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 336, 122455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Carbapenemase Testing for Carbapenem-Resistant Organisms (CRO): A Primer for Clinical and Public Health Laboratories; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CHCQ/HAI/CDPH%20Document%20Library/CRO_PrimerTests_for_Carbapenemases.pdf? (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Zeng, M.; Xia, J.; Zong, Z.; Shi, Y.; Ni, Y.; Hu, F.; Chen, Y.; Zhuo, C.; Hu, B.; Lv, X. Guidelines for the diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control of infections caused by carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacilli. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2023, 56, 653–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Jia, P.; Li, X.; Wang, T.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, G.; Duan, S.; Kang, W.; Xu, Y.; Yang, Q. Carbapenemase detection by NG-Test CARBA 5—A rapid immunochromatographic assay in carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales diagnosis. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Zhou, J.; Li, G.; Liu, R.; Lu, G.; Shen, J. Methodological evaluation of carbapenemase detection by different methods. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2024, 73, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomehzadeh, N.; Rahimzadeh, M.; Ahmadi, B. Molecular detection of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-and carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in southwest Iran. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2024, 29, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECDC. Rapid Risk Assessment: Carbapenemase-Producing (OXA-48) Klebsiella pneumoniae ST392 in Travellers Previously Hospitalised in Gran Canaria, Spain; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018; Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/28-06-2018-RRA-Klebsiella-pneumoniae-Spain-Sweden-Finland-Norway.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Kamruzzaman, M.; Iredell, J.R. CRISPR-Cas system in antibiotic resistance plasmids in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Wu, J.; Xi, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S.; Yang, H.; Duan, G. Association between Type IV-A CRISPR/Cas system and plasmid-mediated transmission of carbapenemase genes in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 301, 128297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackow, N.A.; Shen, J.; Adnan, M.; Khan, A.S.; Fries, B.C.; Diago-Navarro, E. CRISPR-Cas influences the acquisition of antibiotic resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurić, I.; Jelić, M.; Markanović, M.; Kanižaj, L.; Bošnjak, Z.; Budimir, A.; Kuliš, T.; Tambić-Andrašević, A.; Ivančić-Baće, I.; Mareković, I. CRISPR-Cas Dynamics in Carbapenem-Resistant and Carbapenem-Susceptible Klebsiella pneumoniae Clinical Isolates from a Croatian Tertiary Hospital. Pathogens 2025, 14, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamruzzaman, M.; Shoma, S.; Thomas, C.M.; Partridge, S.R.; Iredell, J.R. Plasmid interference for curing antibiotic resistance plasmids in vivo. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, K.N.; Spanogiannopoulos, P.; Soto-Perez, P.; Alexander, M.; Nalley, M.J.; Bisanz, J.E.; Nayak, R.R.; Weakley, A.M.; Yu, F.B.; Turnbaugh, P.J. Phage-delivered CRISPR-Cas9 for strain-specific depletion and genomic deletions in the gut microbiome. Cell Rep. 2021, 37, 109930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kippnich, J.; Benz, F.; Uecker, H.; Baumdicker, F. Effectiveness of CRISPR-Cas in sensitizing bacterial populations with plasmid-encoded antimicrobial resistance. Genetics 2025, 231, iyaf192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, A.; Bhattacharjee, R.; Nandi, A.; Sinha, A.; Kar, S.; Manoharan, N.; Mitra, S.; Mojumdar, A.; Panda, P.K.; Patro, S. Phage delivered CRISPR-Cas system to combat multidrug-resistant pathogens in gut microbiome. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 151, 113122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrancianu, C.O.; Popa, L.I.; Bleotu, C.; Chifiriuc, M.C. Targeting plasmids to limit acquisition and transmission of antimicrobial resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckner, M.M.; Ciusa, M.L.; Piddock, L.J. Strategies to combat antimicrobial resistance: Anti-plasmid and plasmid curing. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 42, 781–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manavalan, V.A.; Vinayagam, S.; Sundaram, T.; Chopra, S.; Chopra, H.; Malik, T. Bacteriophage Therapy in Intensive Care Units: A Targeted Strategy to Combat Multidrug-Resistant Infections—A Review. Methodology 2025, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bris, J.; Chen, N.; Supandy, A.; Rendueles, O.; Van Tyne, D. Phage therapy for Klebsiella pneumoniae: Understanding bacteria–phage interactions for therapeutic innovations. PLoS Pathog. 2025, 21, e1012971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponsecchi, G.; Olimpieri, T.; Poerio, N.; Antonelli, A.; Coppi, M.; Di Lallo, G.; Gentile, M.; Paccagnini, E.; Lupetti, P.; Lubello, C. Characterization of four novel bacteriophages targeting multi-drug resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains of sequence type 147 and 307. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1473668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kim, S.; Choi, Y.-J.; Shin, M.; Kim, J. Characterization of newly isolated bacteriophages targeting carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Microbiol. 2024, 62, 1133–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khambhati, K.; Bhattacharjee, G.; Gohil, N.; Dhanoa, G.K.; Sagona, A.P.; Mani, I.; Bui, N.L.; Chu, D.T.; Karapurkar, J.K.; Jang, S.H. Phage engineering and phage-assisted CRISPR-Cas delivery to combat multidrug-resistant pathogens. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2023, 8, e10381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto Riquelme, M.V.; Garner, E.; Gupta, S.; Metch, J.; Zhu, N.; Blair, M.F.; Arango-Argoty, G.; Maile-Moskowitz, A.; Li, A.-d.; Flach, C.-F. Demonstrating a comprehensive wastewater-based surveillance approach that differentiates globally sourced resistomes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 14982–14993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Punch, R.; Azani, R.; Ellison, C.; Majury, A.; Hynds, P.D.; Payne, S.J.; Brown, R.S. The surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in wastewater from a one health perspective: A global scoping and temporal review (2014–2024). One Health 2025, 21, 101139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martiny, H.-M.; Munk, P.; Fuschi, A.; Becsei, Á.; Pyrounakis, N.; Brinch, C.; Larsson, D.J.; Koopmans, M.; Remondini, D. Geographics and bacterial networks differently shape the acquired and latent global sewage resistomes. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 10278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mustapha, A.I.; Tiwari, A.; Laukkanen-Ninios, R.; Lehto, K.-M.; Oikarinen, S.; Lipponen, A.; Pitkänen, T.; Heikinheimo, A. Wastewater based genomic surveillance key to population level monitoring of AmpC/ESBL producing Escherichia coli. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillay, S.; Calderón-Franco, D.; Urhan, A.; Abeel, T. Metagenomic-based surveillance systems for antibiotic resistance in non-clinical settings. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1066995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcázar, J.L. Wastewater-Based Epidemiology as a Complementary Tool for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance: Overcoming Barriers to Integration. BioEssays 2025, 47, e70034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canada, G. One Health Surveillance for Antimicrobial Resistance and Emerging Pathogens by Targeted Metagenomics at Human–Livestock–Environment Interfaces; Genome Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2025; Available online: https://genomecanada.ca/project/one-health-surveillance-for-antimicrobial-resistance-and-emerging-pathogens-by-targeted-metagenomics-at-human-livestock-environment-interfaces/? (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Djordjevic, S.P.; Jarocki, V.M.; Seemann, T.; Cummins, M.L.; Watt, A.E.; Drigo, B.; Wyrsch, E.R.; Reid, C.J.; Donner, E.; Howden, B.P. Genomic surveillance for antimicrobial resistance—A One Health perspective. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2024, 25, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, K.K.; Olsen, R.J.; Musick, W.L.; Cernoch, P.L.; Davis, J.R.; Peterson, L.E.; Musser, J.M. Integrating rapid diagnostics and antimicrobial stewardship improves outcomes in patients with antibiotic-resistant Gram-negative bacteremia. J. Infect. 2014, 69, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- bioMérieux. Evidence-Based Diagnostics for Antimicrobial Stewardship: Selection of Publications; 2024 Edition; bioMérieux: Marcy-l’Étoile, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.biomerieux.com/content/dam/biomerieux-com/04---our-responsibility/03---healthcare-ecosystem/EVIDENCE-BASED%20DX%20FOR%20AMS%20-%20Selection%20of%20Publications%20Update%202024%20-%20FINAL%20-%20Interactive%20links%20-%2003-24.pdf.coredownload.pdf? (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Madney, Y.; Mahfouz, S.; Bayoumi, A.; Hassanain, O.; Hassanain, O.; Sayed, A.A.; Jalal, D.; Lotfi, M.; Tolba, M.; Ziad, G.A. Carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae (CRE) in children with cancer: The impact of rapid diagnostics and targeted colonization strategies on improving outcomes. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasala, A.; Hytönen, V.P.; Laitinen, O.H. Modern tools for rapid diagnostics of antimicrobial resistance. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, D.; Spellberg, B. Leveraging antimicrobial stewardship into improving rates of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Virulence 2017, 8, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. GLASS Whole-Genome Sequencing for Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/antimicrobial-resistance/glass_wgs_report_v8_web.pdf? (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Jauneikaite, E.; Baker, K.S.; Nunn, J.G.; Midega, J.T.; Hsu, L.Y.; Singh, S.R.; Halpin, A.L.; Hopkins, K.L.; Price, J.R.; Srikantiah, P. Genomics for antimicrobial resistance surveillance to support infection prevention and control in health-care facilities. Lancet Microbe 2023, 4, e1040–e1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECDC. ECDC Strategic Framework for the Integration of Molecular and Genomic Typing into European Surveillance and Multi-Country Outbreak Investigations, 2019–2021; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2021. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/framework-for-genomic-surveillance.pdf? (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Halpin, A.L.; Mathers, A.J.; Walsh, T.R.; Zingg, W.; Okeke, I.N.; McDonald, L.C.; Elkins, C.A.; Harbarth, S.; Peacock, S.J.; Srinivasan, A. A framework towards implementation of sequencing for antimicrobial-resistant and other health-care-associated pathogens. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, e235–e244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarocki, V.M.; Cummins, M.L.; Donato, C.M.; Howden, B.P.; Djordjevic, S.P. A One Health approach for the genomic surveillance of AMR. Microbiol. Aust. 2024, 45, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcom, H.B.; Bowes, D.A. Use of Wastewater to Monitor Antimicrobial Resistance Trends in Communities and Implications for Wastewater-Based Epidemiology: A Review of the Recent Literature. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigozie, V.U.; Aniokete, C.U.; Ogbonna, P.I.; Iroha, R.I. Transforming antimicrobial resistance mitigation: The genomic revolution in one health and public health. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Diagnostic Platform | Molecular Targets | Specimen and Clinical Setting | Clinical Application | Key Findings from Clinical Studies | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real-time PCR for blaKPC from blood cultures | blaKPC | Positive blood culture bottles from patients with suspected bloodstream infection | Early confirmation of blaKPC-producing K. pneumoniae to guide rapid therapy decisions | Detected blaKPC with 100% sensitivity and specificity; limit of detection about 10–20 CFU per reaction | [172] |

| Multiplex real-time PCR for epidemic CRKP clones | blaKPC and ST258-associated markers | Cultured Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates during hospital outbreaks | Rapid identification of high-risk blaKPC-producing ST258 K. pneumoniae | 100% sensitivity and specificity in tested isolates; faster than MLST | [173] |

| Xpert Carba-R NAAT | blaKPC, blaNDM, blaVIM, blaOXA-48-like, blaIMP | Rectal swabs and clinical isolates in screening programs | Rapid detection and classification of carbapenemase genes for infection control | Sensitivity about 93–98% and specificity close to 100% across multiple evaluations | [145,174,175] |

| LAMP assays | K. pneumoniae markers and blaKPC or blaNDM | Cultured isolates and selected clinical samples | Rapid detection of CRKP without thermocyclers | Results within about 60 min with high concordance to PCR | [149,153,154] |

| CRISPR–Cas13a assays | blaKPC and blaNDM | Clinical isolates and simulated clinical samples | Highly sensitive detection of CRKP with portable formats | Detection limits down to a few copies of DNA with full agreement to qPCR | [157,163] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Elbehiry, A.; Marzouk, E.; Abalkhail, A. Molecular Insights into Carbapenem Resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae: From Mobile Genetic Elements to Precision Diagnostics and Infection Control. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1229. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031229

Elbehiry A, Marzouk E, Abalkhail A. Molecular Insights into Carbapenem Resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae: From Mobile Genetic Elements to Precision Diagnostics and Infection Control. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(3):1229. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031229

Chicago/Turabian StyleElbehiry, Ayman, Eman Marzouk, and Adil Abalkhail. 2026. "Molecular Insights into Carbapenem Resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae: From Mobile Genetic Elements to Precision Diagnostics and Infection Control" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 3: 1229. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031229

APA StyleElbehiry, A., Marzouk, E., & Abalkhail, A. (2026). Molecular Insights into Carbapenem Resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae: From Mobile Genetic Elements to Precision Diagnostics and Infection Control. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(3), 1229. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031229