PrPC-Neutralizing Antibody Confers an Additive Benefit in Combination with 5-Fluorouracil in KRAS-Mutant Colorectal Cancer Models, Associated with Reduced RAS-GTP and AKT/ERK Phosphorylation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

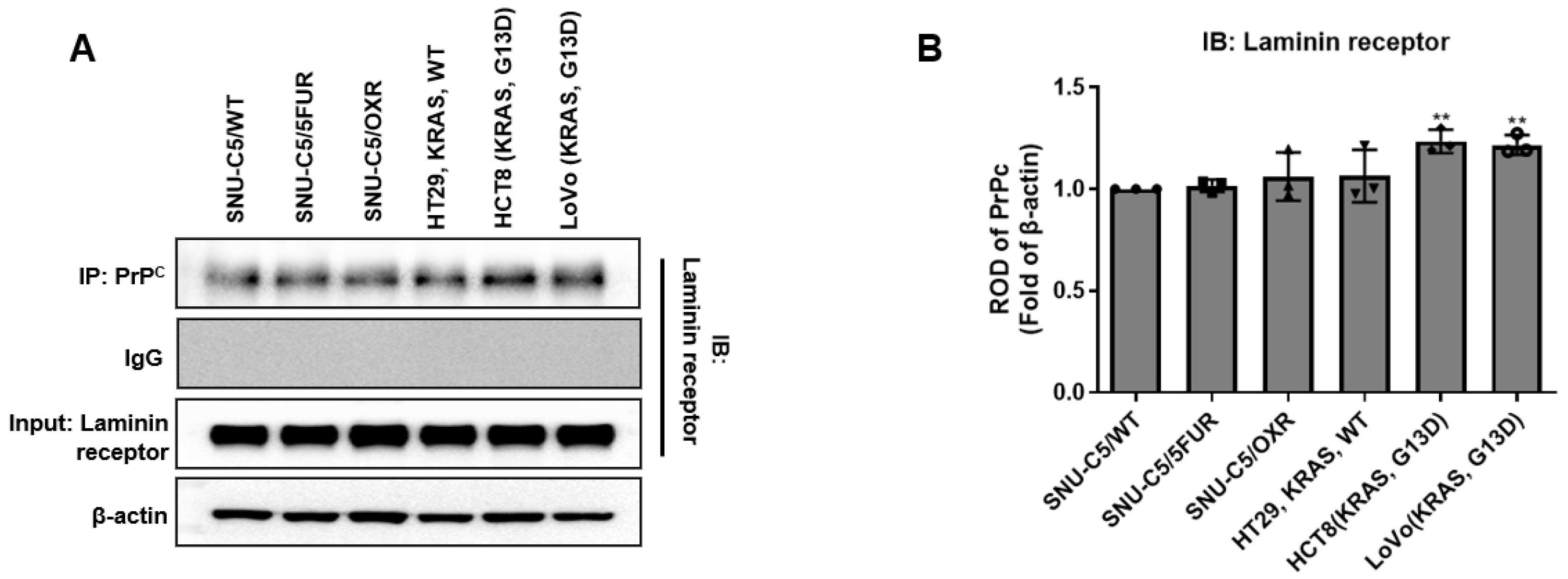

2.1. Co-Immunoprecipitation of PrPC–RPSA Complexes Across Colorectal Cancer Cell Lines

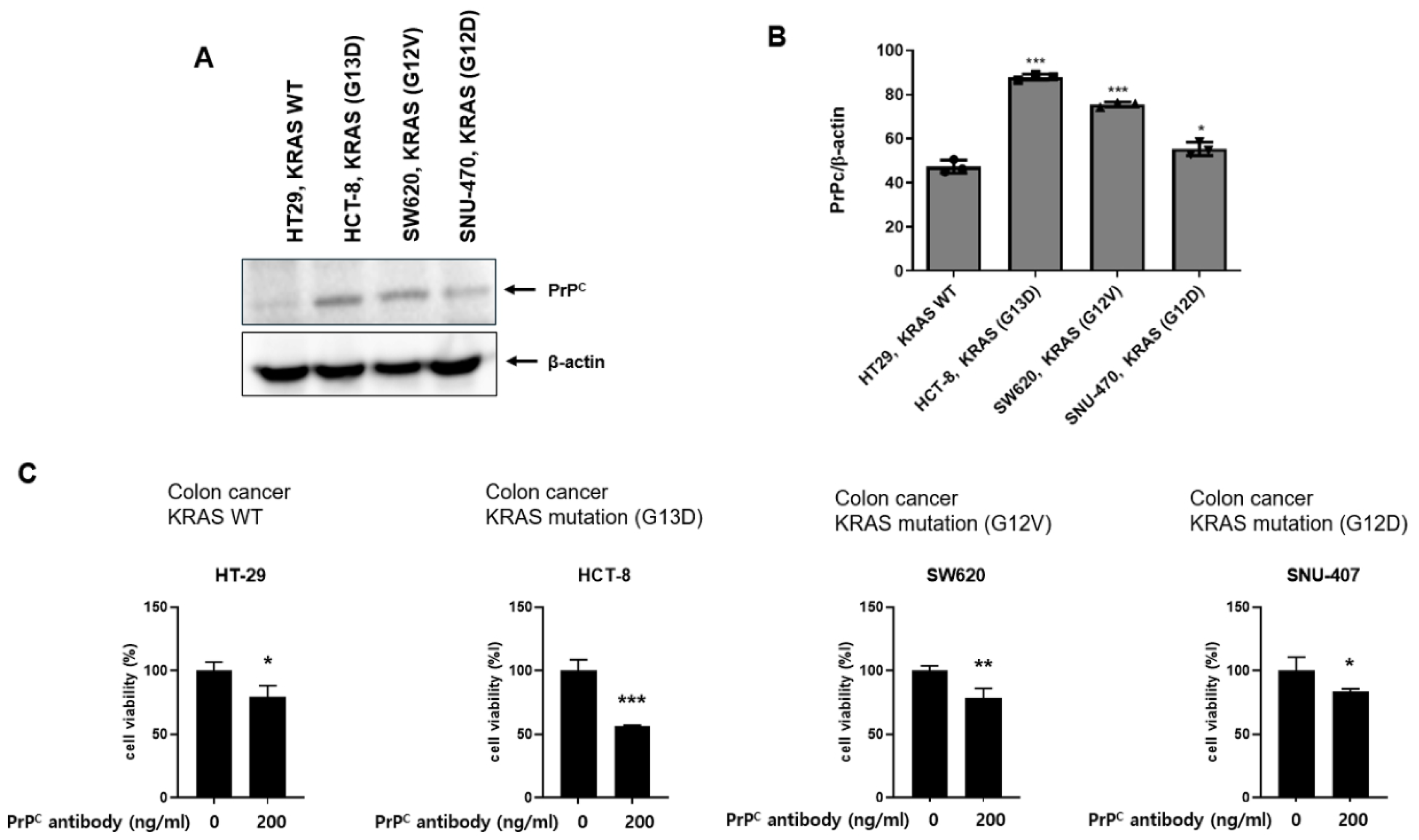

2.2. Neutralizing PrPC Preferentially Reduces Viability in KRAS-Mutant Colorectal Cancer Cells

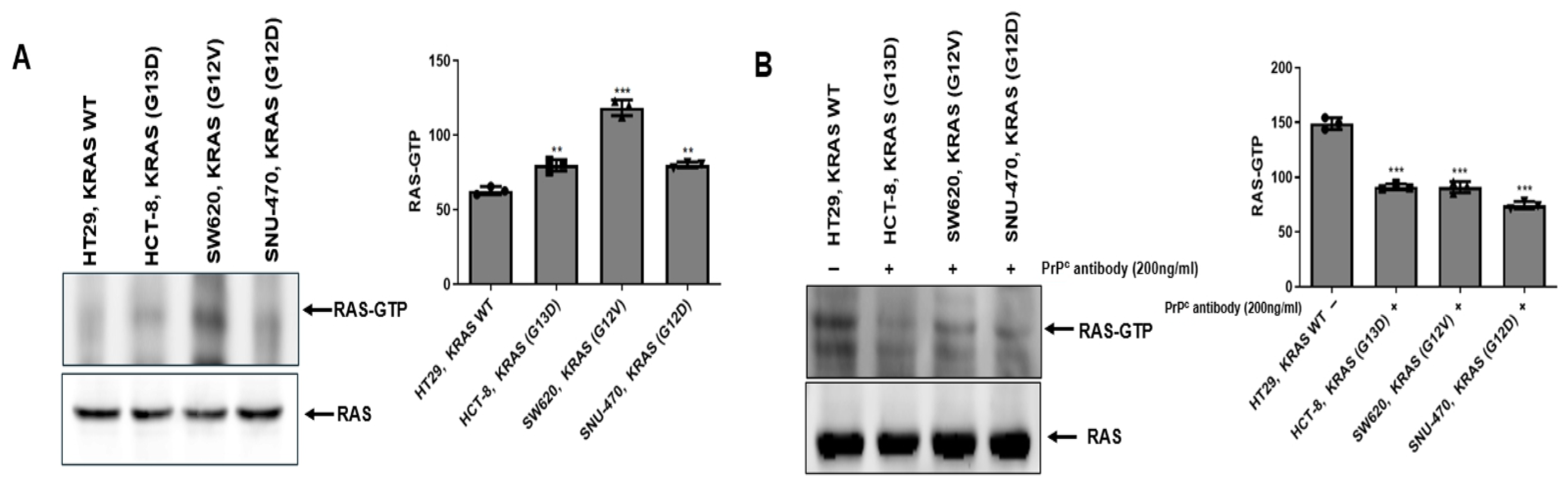

2.3. PrPC Treatment Is Associated with Reduced RAS Activity (RAS-GTP) in KRAS-Mutant Colorectal Cancer Cells

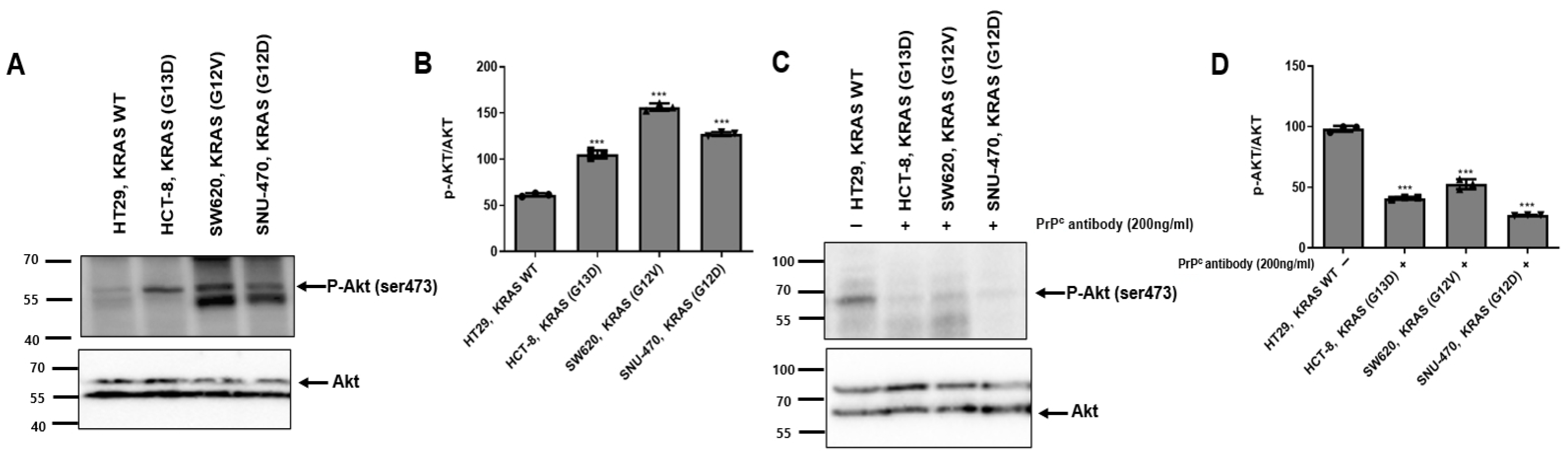

2.4. PrPC Antibody Attenuates AKT Activation in KRAS-Mutant Colorectal Cancer Cells

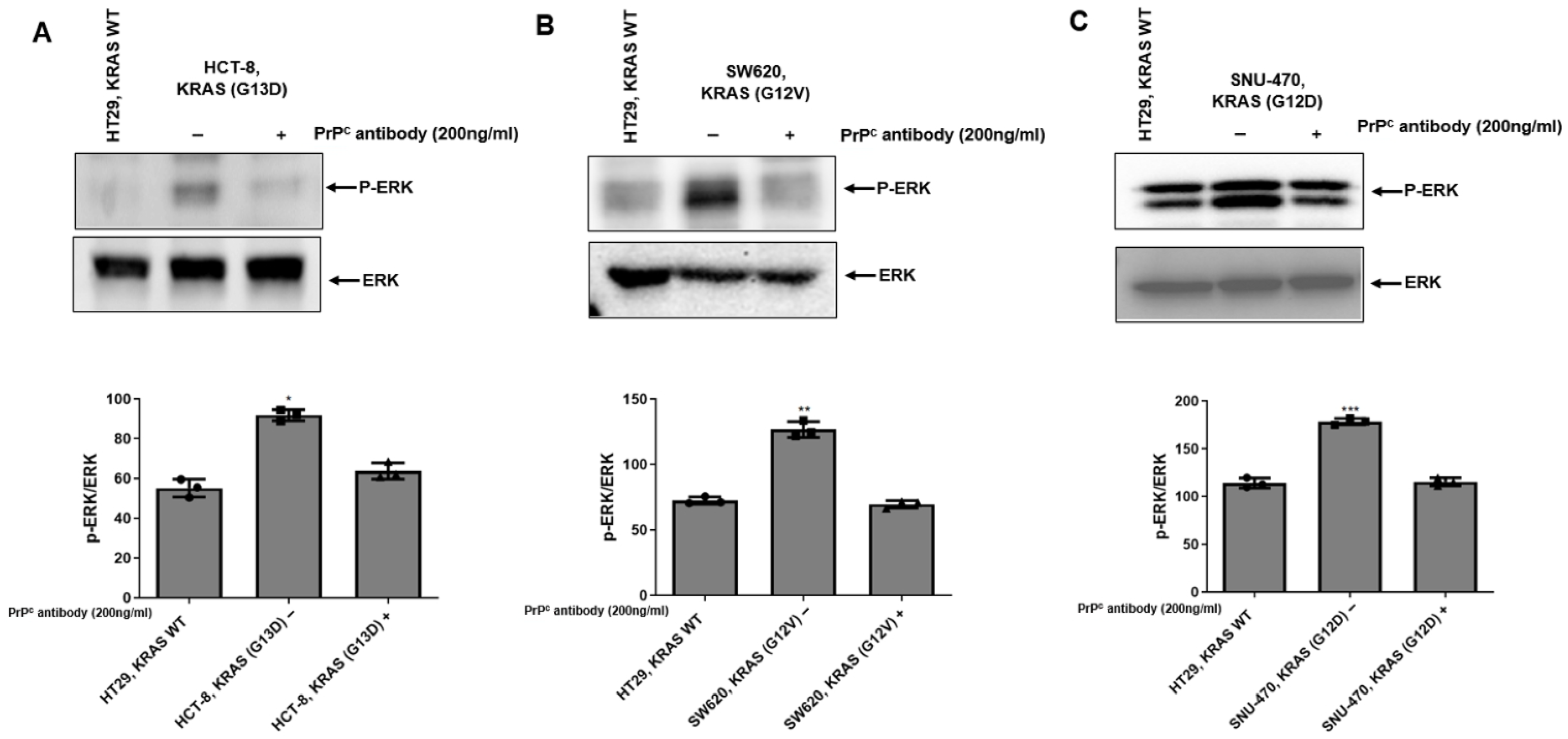

2.5. PrPC Antibody Attenuates ERK Activation in KRAS-Mutant Colorectal Cancer Cells

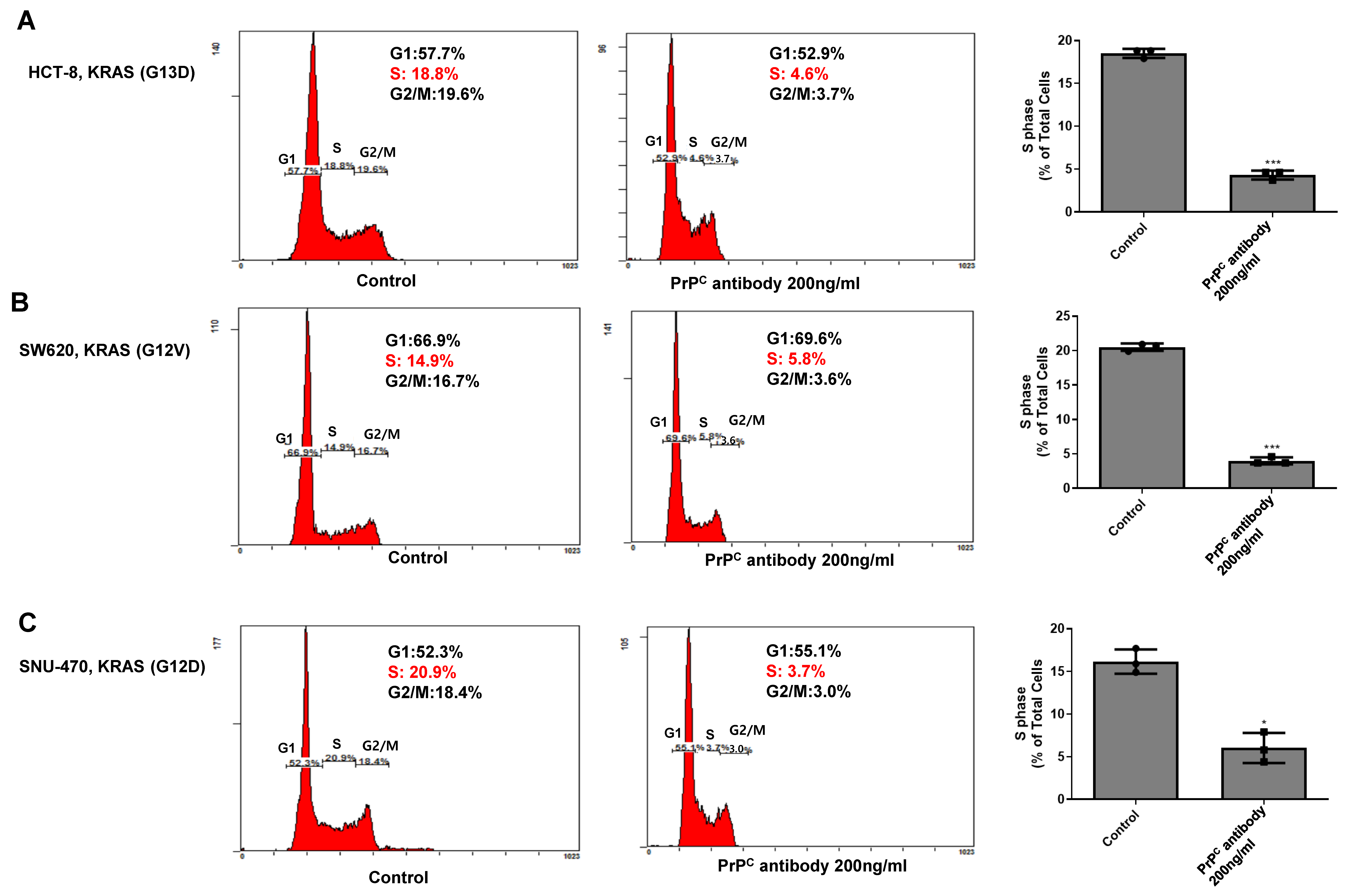

2.6. PrPC Neutralization Decreases S-Phase Entry in KRAS-Mutant Colorectal Cancer Cells

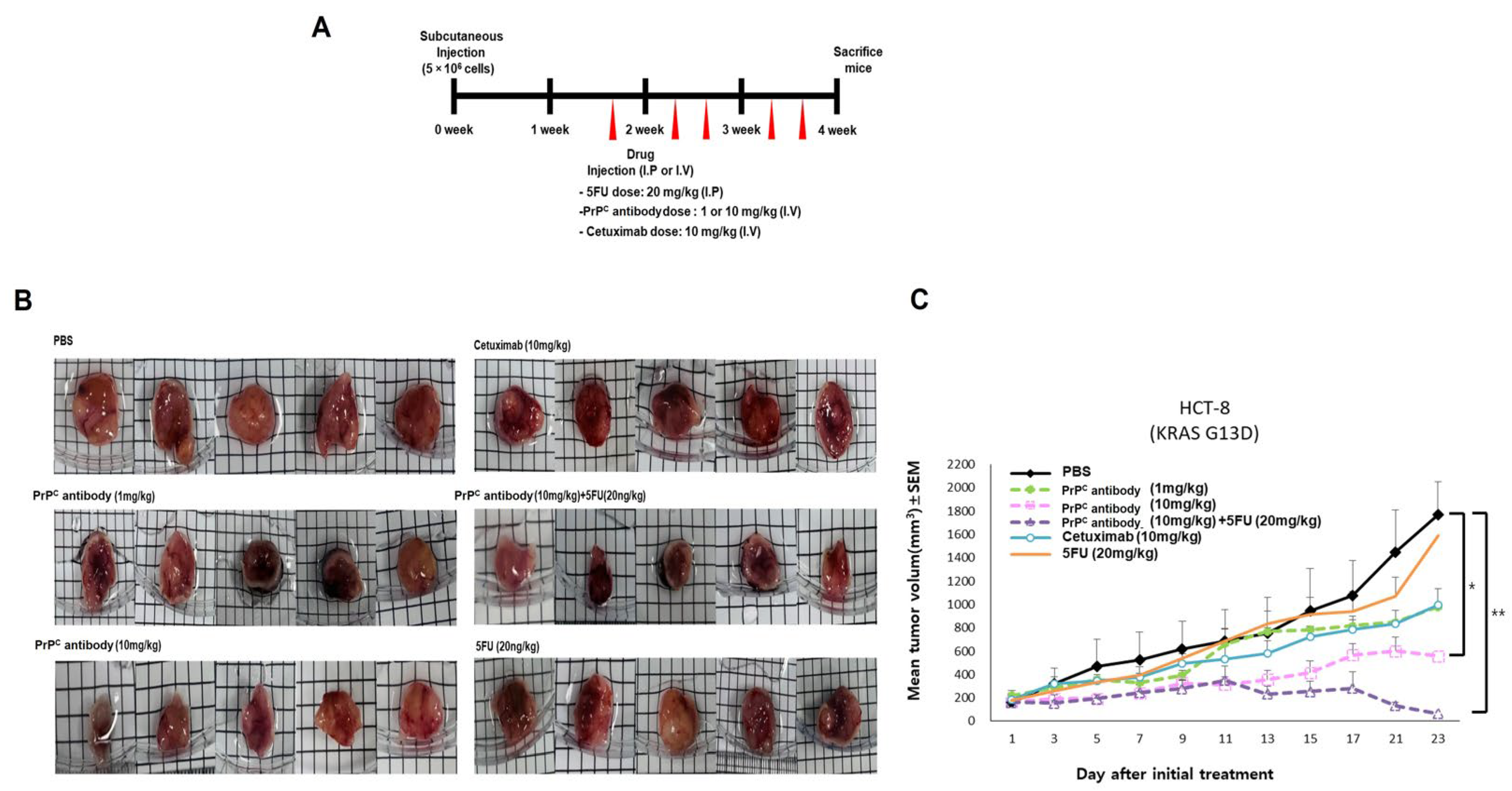

2.7. PrPC Retains Antitumor Activity in a KRAS-Mutant Xenograft and Improves 5-FU Response

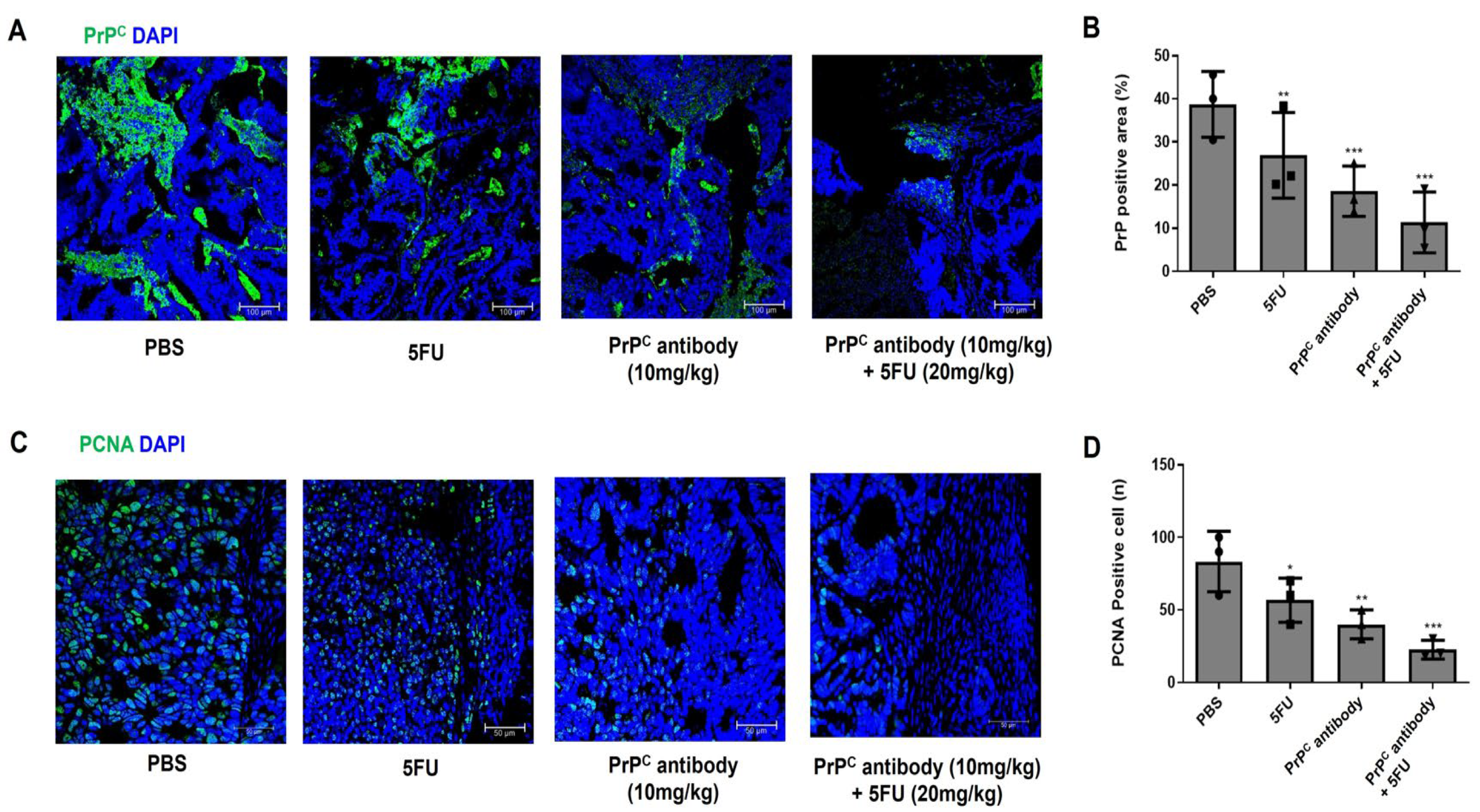

2.8. PrPC Antibody Reduces Intratumoral PrPC and Proliferating Cells in KRAS-Mutant Xenografts

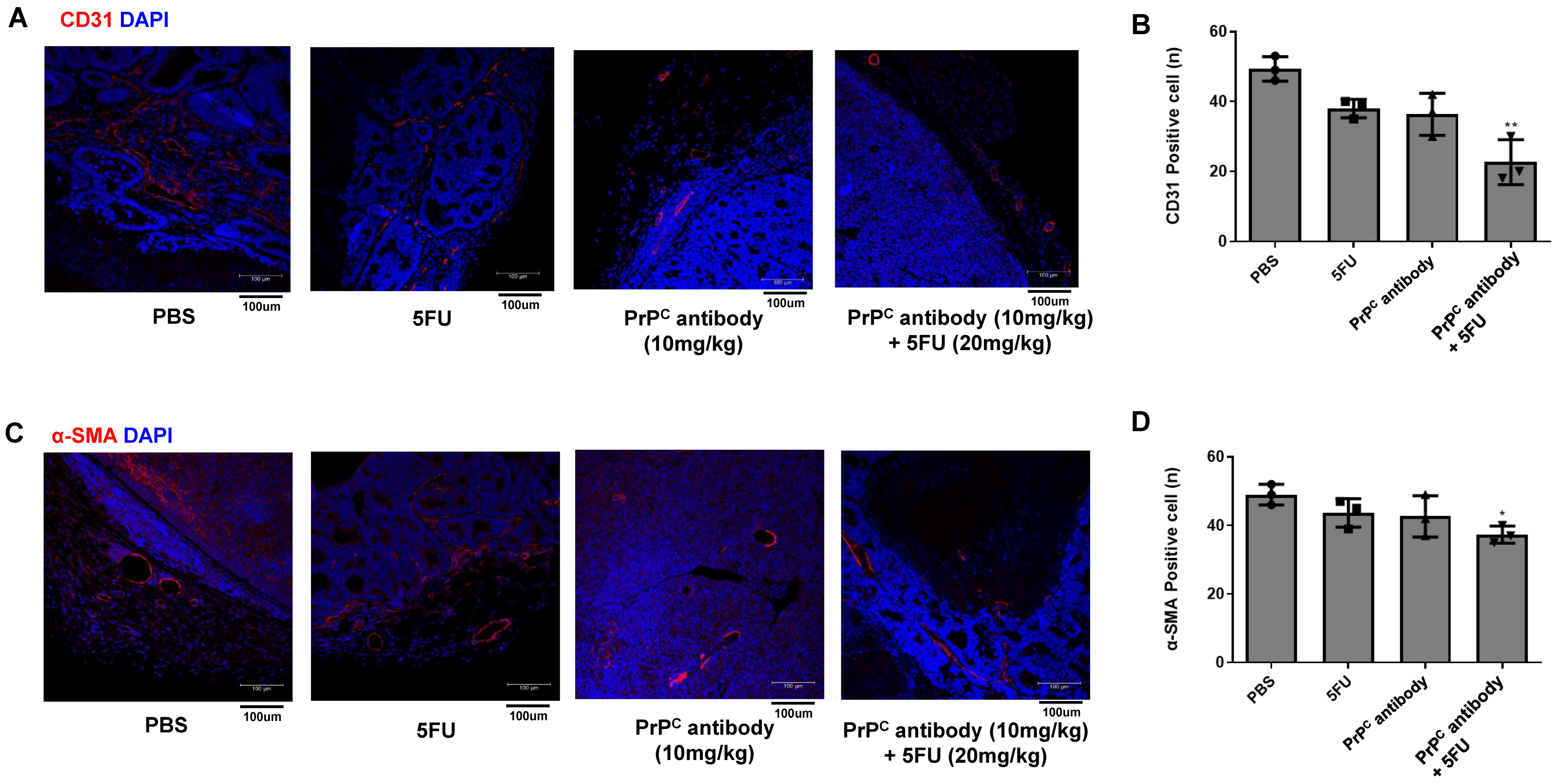

2.9. PrPC Neutralization Reduces Tumor-Associated Vessel Formation in KRAS-Mutant Xenografts

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents and Antibodies

4.2. Epitope Mapping

4.3. Cell Culture

4.4. Co-Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

4.5. Cell Viability Assay with PrPC Antibody

4.6. Ras Activity Assay

4.7. Western Blot Analysis

4.8. Cell Cycle Analysis and Dose Selection for Combination Studies

4.9. Xenograft Studies (HCT-8 KRAS G13D)

4.10. Immunofluorescence Staining

4.11. Statistics

4.12. Ethics

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karapetis, C.S.; Khambata-Ford, S.; Jonker, D.J.; O’Callaghan, C.J.; Tu, D.; Tebbutt, N.C.; Simes, R.J.; Chalchal, H.; Shapiro, J.D.; Robitaille, S.; et al. K-ras mutations and benefit from cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 1757–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douillard, J.-Y.; Oliner, K.S.; Siena, S.; Tabernero, J.; Burkes, R.; Barugel, M.; Humblet, Y.; Bodoky, G.; Cunningham, D.; Jassem, J.; et al. Panitumumab–FOLFOX4 treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1023–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervantes, A.; Adam, R.; Roselló, S.; Arnold, D.; Normanno, N.; Taïeb, J.; Seligmann, J.; De Baere, T.; Osterlund, P.; Yoshino, T.; et al. Metastatic colorectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 10–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauczynski, S.; Peyrin, J.; Haïk, S.; Leucht, C.; Hundt, C.; Rieger, R.; Krasemann, S.; Deslys, J.; Dormont, D.; Lasmézas, C.I.; et al. The 37-kDa/67-kDa laminin receptor acts as the cell-surface receptor for the cellular prion protein. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 5863–5875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, C.J.; Kawamata, F.; Liu, C.; Ham, S.; Győrffy, B.; Munn, A.L.; Wei, M.Q.; Möller, A.; Whitehall, V.; Wiegmans, A.P. EGFR and Prion protein promote signaling via FOXO3a-KLF5 resulting in clinical resistance to platinum agents in colorectal cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2019, 13, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Corre, D.; Ghazi, A.; Balogoun, R.; Pilati, C.; Aparicio, T.; Martin-Lannerée, S.; Marisa, L.; Djouadi, F.; Poindessous, V.; Crozet, C.; et al. The cellular prion protein controls the mesenchymal-like molecular subtype and predicts disease outcome in colorectal cancer. eBioMedicine 2019, 46, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hundt, C.; Peyrin, J.-M.; Haïk, S.; Gauczynski, S.; Leucht, C.; Rieger, R.; Riley, M.L.; Deslys, J.-P.; Dormont, D.; Lasmézas, C.I.; et al. Identification of interaction domains of the prion protein with its 37-kDa/67-kDa laminin receptor. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 5876–5886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.H.; Go, G.; Lee, S.H. PrPC Regulates the cancer stem cell properties via interaction with c-Met in colorectal cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2021, 41, 3459–3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lacerda, T.C.S.; Costa-Silva, B.; Giudice, F.S.; Dias, M.V.S.; de Oliveira, G.P.; Teixeira, B.L.; dos Santos, T.G.; Martins, V.R. Prion protein binding to HOP modulates the migration and invasion of colorectal cancer cells. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2016, 33, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.; Rao, G.; Wang, H.; Li, B.; Tian, W.; Cui, J.; He, L.; Laffin, B.; Tian, X.; Hao, C.; et al. CD44-Positive cancer stem cells expressing cellular prion protein contribute to metastatic capacity in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 2682–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Yun, C.W.; Lee, S.H. Cellular prion protein enhances drug resistance of colorectal cancer cells via regulation of a survival signal pathway. Biomol. Ther. 2018, 26, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Han, Y.-S.; Yoon, Y.M.; Yun, C.W.; Yun, S.P.; Kim, S.M.; Kwon, H.Y.; Jeong, D.; Baek, M.J.; Lee, H.J.; et al. Role of HSPA1L as a cellular prion protein stabilizer in tumor progression via HIF-1α/GP78 axis. Oncogene 2017, 36, 6555–6567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corsaro, A.; Bajetto, A.; Thellung, S.; Begani, G.; Villa, V.; Nizzari, M.; Pattarozzi, A.; Solari, A.; Gatti, M.; Pagano, A.; et al. Cellular prion protein controls stem cell-like properties of human glioblastoma tumor-initiating cells. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 38638–38657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryskalin, L.; Biagioni, F.; Busceti, C.L.; Giambelluca, M.A.; Morelli, L.; Frati, A.; Fornai, F. The role of cellular prion protein in promoting stemness and differentiation in cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, D.R.; Hooper, N.M. The prion protein and lipid rafts (Review). Mol. Membr. Biol. 2006, 23, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, J.; Choe, V.; Cheng, H.; Tsai, Y.C.; Weissman, A.M.; Luo, S.; Rao, H. Ubiquitin ligase gp78 targets unglycosylated prion protein PrP for ubiquitylation and degradation. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.-Y.; Jeong, J.-K.; Lee, J.-H.; Moon, J.-H.; Kim, S.-W.; Lee, Y.-J.; Park, S.-Y. Induction of cellular prion protein (PrPc) under hypoxia inhibits apoptosis caused by TRAIL treatment. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 5342–5353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Knoll, G.; Bittner, S.; Kurz, M.; Jantsch, J.; Ehrenschwender, M. Hypoxia regulates TRAIL sensitivity of colorectal cancer cells through mitochondrial autophagy. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 41488–41504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lee, J.; JunYoung, Y.; Young, L.J.; Lee, S.H. PrPC-Neutralizing Antibody Confers an Additive Benefit in Combination with 5-Fluorouracil in KRAS-Mutant Colorectal Cancer Models, Associated with Reduced RAS-GTP and AKT/ERK Phosphorylation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1159. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031159

Lee J, JunYoung Y, Young LJ, Lee SH. PrPC-Neutralizing Antibody Confers an Additive Benefit in Combination with 5-Fluorouracil in KRAS-Mutant Colorectal Cancer Models, Associated with Reduced RAS-GTP and AKT/ERK Phosphorylation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(3):1159. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031159

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Jeongkun, Yoon JunYoung, Lee Jae Young, and Sang Hun Lee. 2026. "PrPC-Neutralizing Antibody Confers an Additive Benefit in Combination with 5-Fluorouracil in KRAS-Mutant Colorectal Cancer Models, Associated with Reduced RAS-GTP and AKT/ERK Phosphorylation" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 3: 1159. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031159

APA StyleLee, J., JunYoung, Y., Young, L. J., & Lee, S. H. (2026). PrPC-Neutralizing Antibody Confers an Additive Benefit in Combination with 5-Fluorouracil in KRAS-Mutant Colorectal Cancer Models, Associated with Reduced RAS-GTP and AKT/ERK Phosphorylation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(3), 1159. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031159