1. Introduction

High-energy ionizing radiation arises from both natural and human-made sources that can ionize atoms [

1]. Life-threatening doses of ionizing radiation can arise from nuclear detonations, severe reactor or criticality accidents, unshielded high-activity sources in industry, radiotherapy misadministration, and extreme solar particle events affecting astronauts. Medical countermeasures are vital to rapidly reduce radiation injury, prevent complications, and improve survival [

2]. Ionizing radiation disrupts the chemical bonds within molecules, which is highly damaging, especially in living tissues. Ionizing radiation primarily damages human health by disrupting cellular processes and DNA structure. This damage can lead to a range of effects, depending on the dose and exposure time. Severely damaged cells may undergo programmed cell death or necrosis [

3]. When enough cells in a tissue or organ are damaged or die, the organ’s function is impaired, leading to symptoms like skin burns, gastrointestinal distress, bone marrow suppression, or organ failure [

1]. Ionizing radiation severely suppresses the immune system by damaging and depleting highly radiosensitive immune cells, particularly lymphocytes and their bone marrow precursors [

1]. This leads to a compromised ability to fight infections and an impaired capacity for tissue repair and immune surveillance.

Ionizing radiation significantly impacts macrophages by causing direct DNA damage and indirectly generating harmful free radicals, leading to their dysfunction or death. This results in impaired phagocytosis, altered cytokine production (often shifting towards a pro-inflammatory or pro-fibrotic profile), and modulated ability to present antigens [

4,

5,

6].

Macrophage extracellular traps (METs) are web-like structures released by macrophages into the extracellular space, primarily composed of decondensed chromatin (DNA and associated histones) and various antimicrobial proteins and enzymes [

7]. Like neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), the main function of METs is to physically trap and concentrate pathogens (like bacteria, fungi, viruses, and parasites), preventing their dissemination and allowing the embedded proteins to neutralize or kill them [

7]. MET formation has significant clinical implications in various diseases, including autoimmune diseases, cardiovascular disorders, cancer, infectious diseases, chronic inflammation conditions, and neurological disorders [

8].

Peptidyl arginine deiminase (PAD) enzymes are required for initiating the formation of METs [

9]. By chemically modifying histones through a process called citrullination, PADs cause the tightly packed chromatin to decondense and unravel. This released web of DNA then forms the structural backbone of the MET, which is expelled from the cell to trap pathogens. PAD2- and PAD4-mediated histone citrullination loosens chromatin. Intracellular granules help decondense DNA, which is ultimately expelled, either by suicidal membrane rupture or via vesicular export, in a vital process [

10,

11].

Gasdermin D (GSDMD) was discovered as the executioner of pyroptosis in 2015, and the release of IL-1β and IL-18 (and likely other IL-1 family members) was found to be dependent on GSDMD [

12,

13]. It was activated by inflammasome both dependently and independently [

14]. The protein consists of an N-terminal pore-forming domain and a C-terminal inhibitory domain, with a cleavage site in the linker between the two domains at position D276 in mice and D275 in humans. GSDMD plays a crucial role in the release of METs [

11,

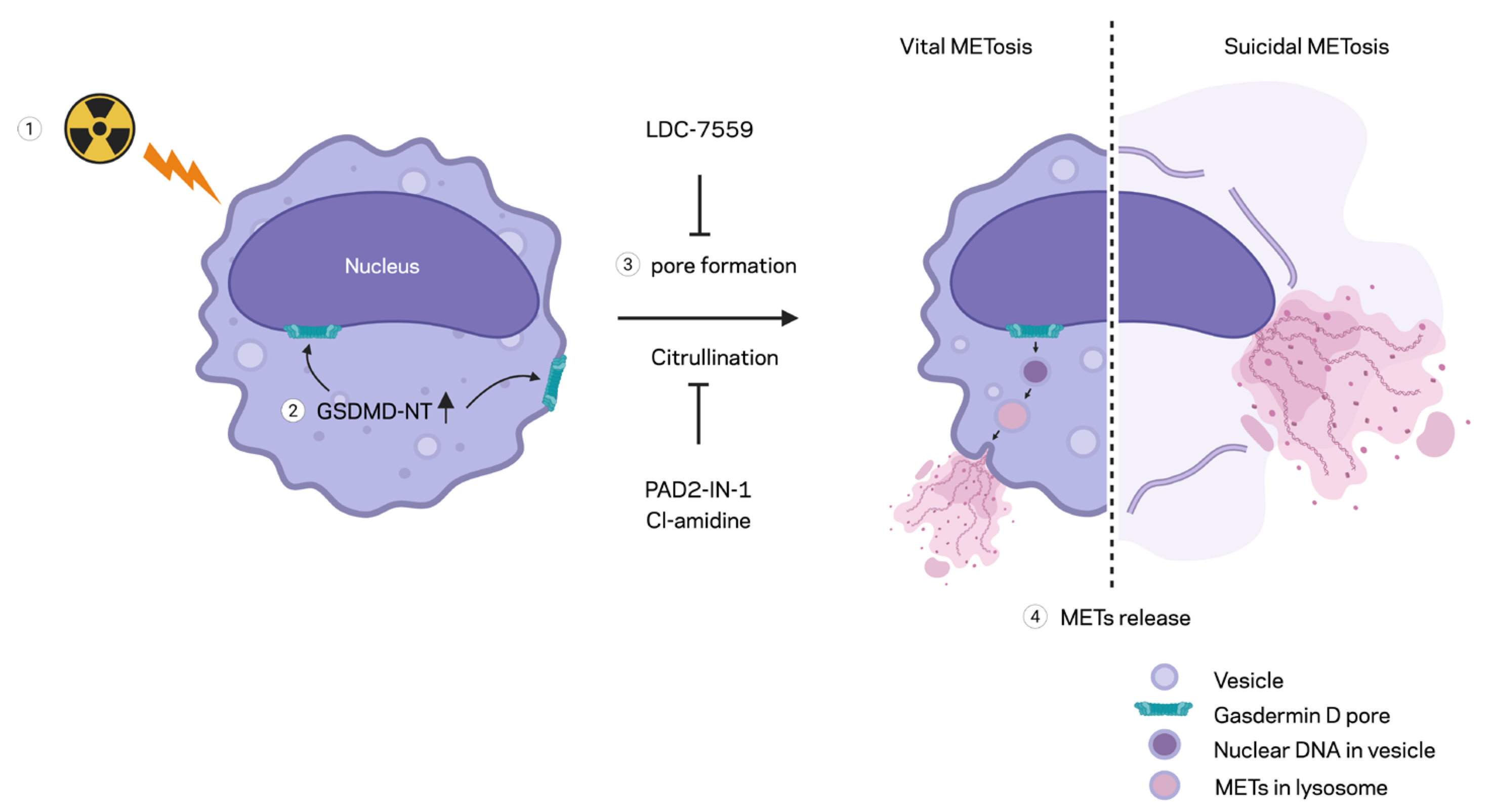

15]. Upon activation by extracellular cold-inducible RNA-binding protein (eCIRP), cleaved GSDMD forms large pores in the macrophage’s cell membrane. This pore formation leads to cell rupture, an inflammatory cell death process known as pyroptosis, which expels the pre-formed MET scaffold from the cell’s interior into the surrounding environment to combat pathogens.

Exposure to ionizing radiation resulted in extracellular trap formation from neutrophils [

16]. However, any evidence of macrophage extracellular trap formation by ionizing radiation has not yet been reported. In this study, we discovered that macrophages release their DNA to the extracellular space in response to ionizing radiation. This extracellular DNA was modified in its histone protein with citrullination, and the process was dependent on the activation of GSDMD and PAD enzymatic activity. Thus, our findings shed light on how radiation exposure compromises macrophage function and identify a new therapeutic target to mitigate radiation-induced immune cell dysfunction.

3. Discussion

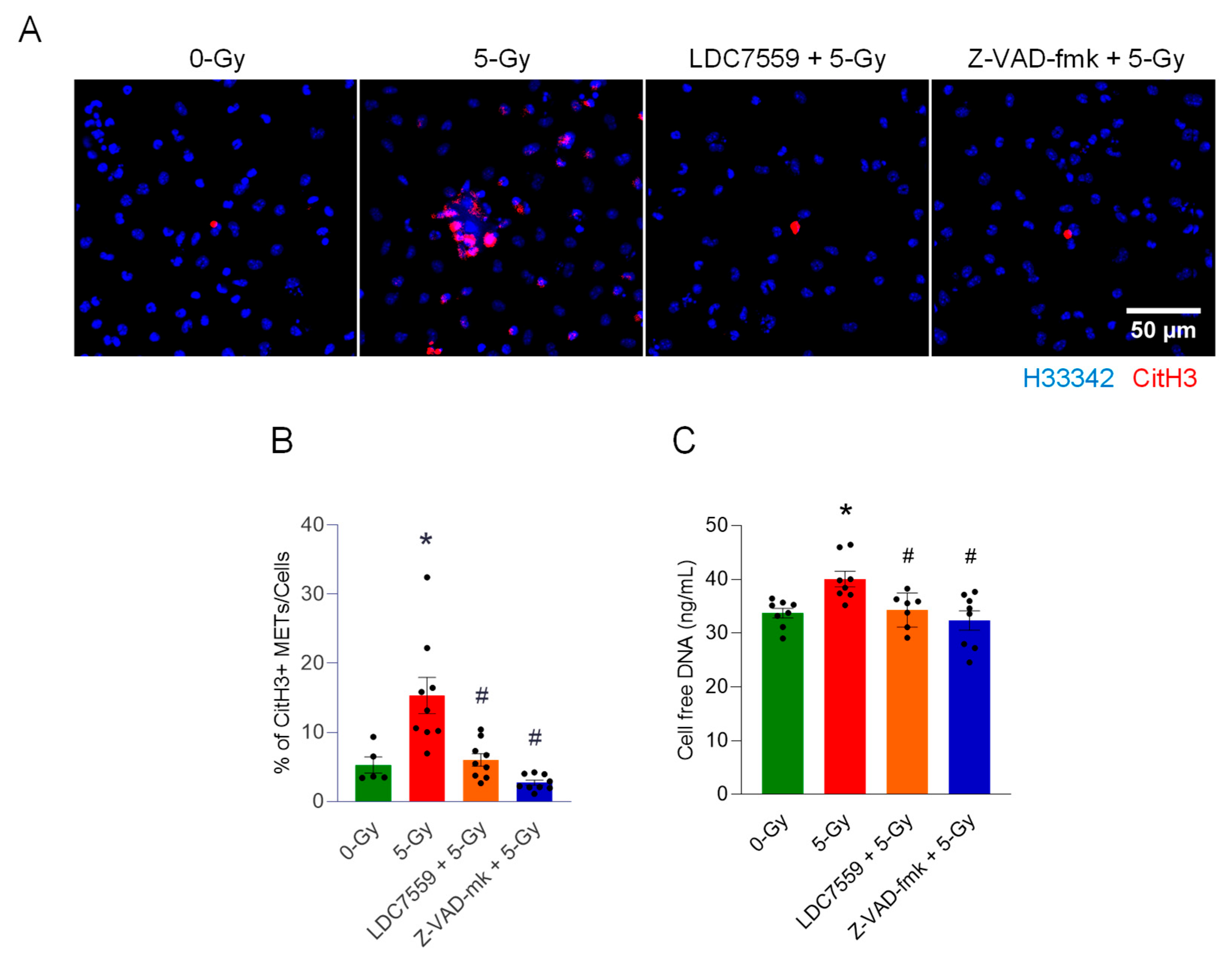

In this study, we demonstrated the formation of extracellular traps in mouse peritoneal macrophages exposed to ionizing radiation. The METs induced by ionizing radiation carried components like citrullination of histone and MPO, as they were observed in different circumstances and routes of release, including suicidal and vesicular transport. Employing a GSDMD inhibitor and PAD inhibitors, we showed the involvement of GSDMD in MET formation and, furthermore, the indispensable role of PADs (

Figure 6). Our study showed radiation exposure induced pyroptotic cell death in macrophages and the release of extracellular traps. Radiation modulates macrophage phenotype and function, often shifting cytokine profiles and surface marker expression. It can impair phagocytic capacity while altering the secretion of inflammatory mediators [

6,

17]. At higher doses, radiation increases macrophage cell death, reducing tissue homeostatic support. Ionizing radiation generates DNA damage and oxidative stress, which can activate danger-sensing pathways in exposed cells. Radiation-induced damage engages priming inflammasome components such as NLRP3 [

18]. Activation of inflammasomes leads to caspase-1 (or caspase-4/5/11 in the noncanonical route) cleavage of GSDMD, creating pore-forming N-terminal fragments. GSDMD pores perforate the plasma membrane, causing ionic fluxes, cell swelling, and the release of IL-1β and IL-18. The culmination is lytic cell death (pyroptosis), which amplifies inflammation and can exacerbate radiation tissue injury. Both suicidal and vital METosis were observed in this study. Suicidal METosis is a trap-forming process in which a macrophage undergoes terminal cell death, characterized by chromatin decondensation, membrane rupture, and the release of DNA strands decorated with granule enzymes into the extracellular space [

7,

15]. Vital METosis, in contrast, allows macrophages to expel extracellular traps while preserving plasma membrane integrity and continued viability, via vesicular export of DNA [

11].

We also showed the involvement of PAD2 and 4 in disseminating the extracellular traps of macrophages exposed to radiation. We employed two enzyme inhibitors, PAD2-IN-1 and Cl-amidine. Both inhibitors were characterized, as they inhibit the isoforms of PAD differentially. PAD2-IN-1 is known to preferentially affect PAD2 95-fold higher than PAD4, whereas Cl-amidine has broad specificity for PADs, including PAD1, PAD3, and PAD4. Both inhibitors effectively inhibited MET formation in the macrophages exposed to the ionizing radiation. To evaluate the activity of PADs, we probed the citrullination of histone H3 protein, which has been frequently used as a marker of extracellular trap detection [

19]. Protein citrullination is a post-translational modification (PTM) that is catalyzed by the PAD family of enzymes. Among the isoforms of PAD, PAD2 and PAD4 were identified as required for macrophages generating extracellular traps [

9]. In our study, the treatment of both inhibitors decreased not only the citrullination of histone but also the cell-free DNA measurement, which includes the levels of LDC7559 and Z-VAD-fmk. This reminds us that the inhibition of PADs has profound effects on cellular physiology, including cell death, inflammation, and DNA/RNA processing pathways, in macrophages [

20,

21].

Radiation-induced extracellular traps have been observed in neutrophils [

22]. NETs generated by ionizing radiation exacerbate subsequent infection and inflammation after exposure to ionizing radiation. It was demonstrated that NETs were generated with the activation of the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1. NET is also considered as an important prognostic implication due to NET’s association with metastases, therapeutic resistance, and immunosuppression [

16,

23]. Here, we showed that macrophages could release extracellular traps as low as 5 Gy in vitro. Though we showed the requirement of GSDMD and PADs in the formation of MET by radiation, we still need to identify how the MET formation is controlled by upstream signaling in detail. Even though we successfully demonstrated the MET formation in the cells exposed to a single radiation dose of 5 Gy in vitro, due to the lack of systemic investigation, which was beyond the scope of current study, on the role of macrophage extracellular traps in response to ionizing radiation, there remain open questions on what dose is sufficient to induce MET formation and cause tissue injury as mediated by the METs produced. Further systemic investigations in the future are anticipated. These will provide invaluable information about susceptibility to the injury caused by radiation-induced METs in different organs like the peritoneum, spleen, and others due to subsequent infection and inflammation.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents

Hoechst 33342 (H33342) (cat. no. R37605) and SYTOX Orange (cat. no. S11368) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Antibodies against cleaved Gasdermin D (cat. no. 10137), Gasdermin D (cat. no. 39754), and LC3B (cat. no. 2775) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Anti-GAPDH antibody (cat. No. 60004-1-Ig) was purchased from Proteintech (Rosemont, IL, USA). Anti-MPO-FITC (cat. no. ab90812), Alexa Fluor 647 anti-LAMP1 antibody (cat. No. ab237307), and anti-histone H3 (citrulline R2 + R8 + R17) antibody (cat. no. ab281584) were purchased from Abcam (Waltham, MA, USA). Z-VAD-fmk (final concentration, 20 μM) was purchased from Sellekchem, Houston TX, USA (cat no. S7023). LDC7559 (final concentration, 10 μM), Cl-amidine (Final concentration, 10 μM), and PAD2-IN-1 (AFM32a hydrochloride) (final concentration, 20 μM) were purchased from MedChemExpress (Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA). Inhibitors were all dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Inhibitor treatment was performed 30 min prior to the radiation treatment. DMSO (final concentration, 0.5% v/v) was used as a control. Inhibitor treatment was continued for 24 h.

4.2. Experimental Animals

C57BL/6 wild-type male mice (8 to 12 weeks) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Mice were housed in a temperature-controlled environment under a 12 h light cycle with ad libitum access to standard rodent chow and water. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines for using experimental animals by the National Institutes of Health. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research.

4.3. Cell Culture

Mouse peritoneal lavage was performed to collect peritoneal cells from unstimulated normal mice [

24]. The mouse peritoneum was flushed with 10 mL cold PBS supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum. For each experiment, peritoneal exudate cells from 8–12 mice were collected by centrifuge 400×

g for 10 min at 4 °C and pooled. Cells were seeded in a cell culture vessel and incubated overnight. Cells were maintained in RPMI media with fetal bovine serum (10%) and penicillin–streptomycin. In 12-well plate cells, 12 mL of peritoneal cell suspension from 6 mice was aliquoted to each well. For 6-well plate cells, 12 mL of peritoneal cell suspension from 6 mice was aliquoted to each well. The culture vessel was then washed 3 times with fresh cell culture medium after overnight incubation. The inhibitor was applied 30 min before the radiation exposure. Cell culture was maintained for 24 h after radiation treatment. Samples were collected and processed for further analysis.

4.4. X-Ray Irradiation

Peritoneal macrophages were subjected to a single dose of 5 Gy with an X-ray irradiation system, X-Rad320 (Precision X-Ray Inc., Madison, CT, USA). Cells were incubated for 24 h after irradiation.

4.5. Time-Lapse Microscopy

Time-lapse microscopy was performed with an Incucyte live imaging system (Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany). Time-lapse images were recorded for 16 h at intervals of 15 min. Transmit light and red channel were recorded for detecting SYTOX Orange dead-cell staining. For live-cell imaging, glass-bottom culture plates were used. The 35 mm glass-bottom culture dish (part no.: P35G-1.5-20-C) and 6-well (part no.: P06G-1.5-20-F) and 12-well (part no.: P12G-1.5-14-F) plates were purchased from MatTek Life Sciences (Ashland, MA, USA).

4.6. Immunofluorescence

Cells were incubated for 24 h after radiation exposure, fixed for 15 min at room temperature with paraformaldehyde (4%), and washed 3 times with PBS. The fixed cells were immediately blocked with blocking buffer (5% BSA and 100 mM glycine in PBS) for 2 h, followed by the incubation of the primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. Antibody was diluted in the blocking buffer according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The cells were then washed 3 times with PBS and incubated with fluorescence tagged secondary antibody for 2 h. After washing the cells 3 times with PBS, the immunofluorescence specimen was prepared by adding prolong gold antifade (cat. no.: P36934, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

4.7. Confocal Microscopy

Images with high resolution were obtained using the Zeiss Axio Observer.Z1/7 equipped with an LSM900 Airyscan confocal system (White Plains, NY, USA). Images of cells were acquired as a z-stack with a Plan-Apochromat 63×/1.40 Oil DIC M27 objective lens. The SR-4Y fast Airyscan acquisition mode and 4× averaging was used. The z-stack images obtained by Airyscan were merged and combined by FIJI ImageJ (Version 1.54p, National Institute of Health, USA) [

25].

4.8. Quantitative Image Analysis

Low-magnification confocal images with immunofluorescence staining were acquired and analyzed by FIJI ImageJ. The Plan-Apochromat 10X/0.45 M27 objective was used for imaging. Nuclear counting was performed with Hoechst 33342 image. Citrullinated Histone H3 (CitH3) quantification was conducted using immunofluorescence staining with anti-citrullinated Histone H3 antibody. To quantify the CitH3 signal only in the MET area, the CitH3 signal in the nuclear region was removed by applying the ROI of the nuclear region. Then, the MET region was counted by generating a binary mask with thresholding command. The resulting MET count was normalized by the number of nuclei in the field.

4.9. Western Blotting

The cell-free lysate of macrophages was prepared by incubating RIPA buffer in each sample. The lysis buffer was supplemented with Sodium Orthovanadate (2 mM), phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) (0.2 mM), and cOmplet mini-protease inhibitor cocktail from Roche (cat. No.: 11836153001; Millipore, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). The protein content of the lysate was determined with a protein assay reagent (cat. no.: 5000002, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Each sample was separated by SDS-PAGE using 4–12% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen, NP0322, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Proteins in the gel were then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane by the X cell II blot module. The membrane was incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C, followed by the incubation of Odyssey secondary antibody (cat. no.: 926-32211 or 926-68070, Lycor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA). The detection and quantification of Western blot was performed by the Odyssey CLx imaging system (Lycor Biosciences).

4.10. Cell-Free DNA Quantification

All cell samples were prepared in 12-well culture plates and maintained with 1 mL cell culture medium per each well in the plate. Cell culture media samples were collected at 24 h after radiation exposure by pipetting. The bottom of each well of the plate was flushed 5 times. EDTA (10 mM) was added to the sample to prevent DNase enzyme activity in the media. The culture media were subjected to centrifuge, 400× g for 10 min at 4 °C. The cell pellets were discarded, and the supernatants were immediately used for DNA measurement with a picogreen DNA quantification kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

4.11. Statistical Analysis

Data represented in the figures are expressed as mean ± SEM. The two-tailed Student’s t-test was used for two-group comparison, and one-way ANOVA with the post hoc Tukey test was used for multiple-group comparison. A statistical significance threshold was considered for p ≤ 0.05 between study groups. Data analyses and graph preparation were carried out using GraphPad Prism (Version 10.2.0 (392)) graphing and statistical software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).