Defining the Critical Role of α-Gustducin for NF-κB Inhibition and Anti-Inflammatory Signal Transduction by Bitter Agonists in Lung Epithelium

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

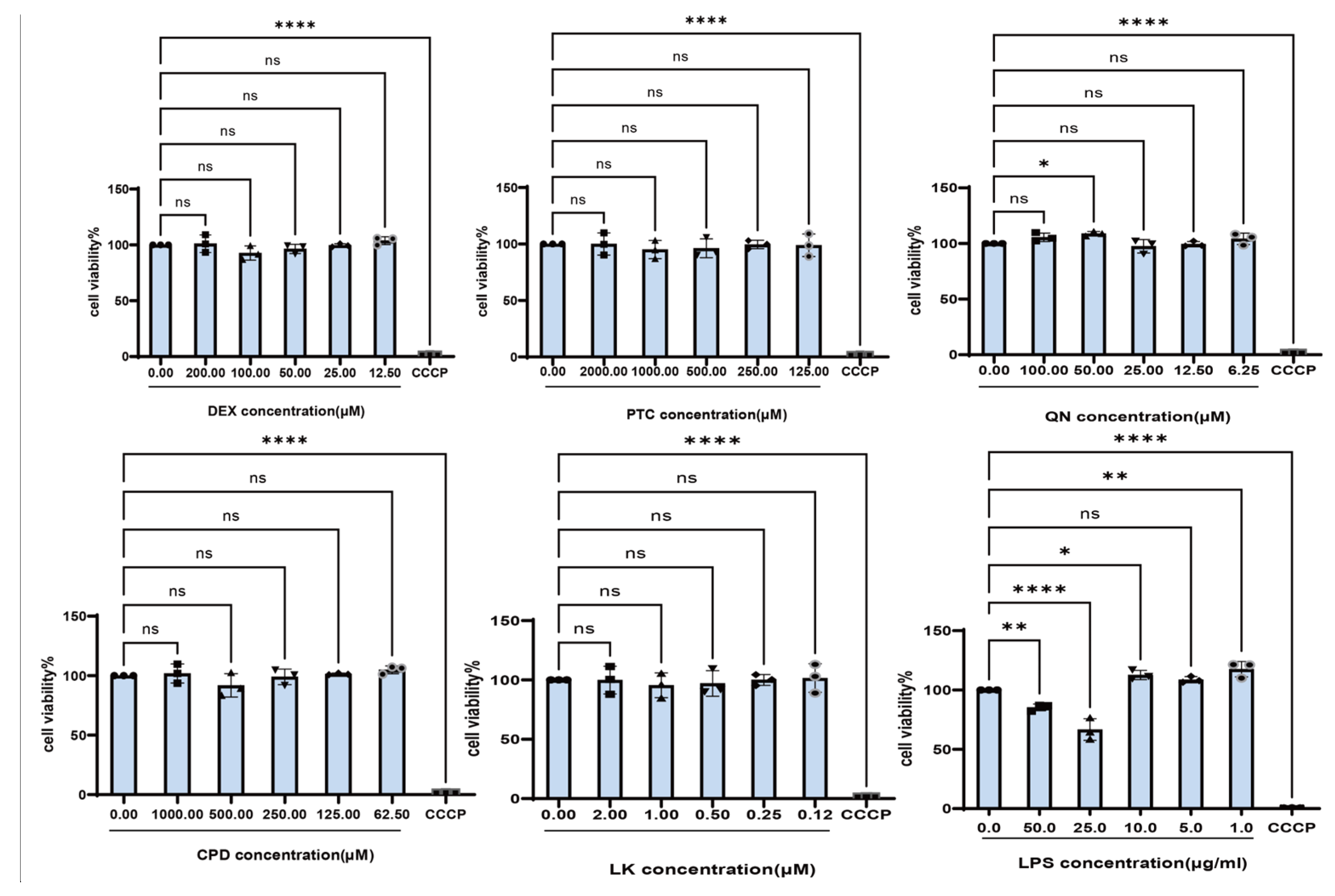

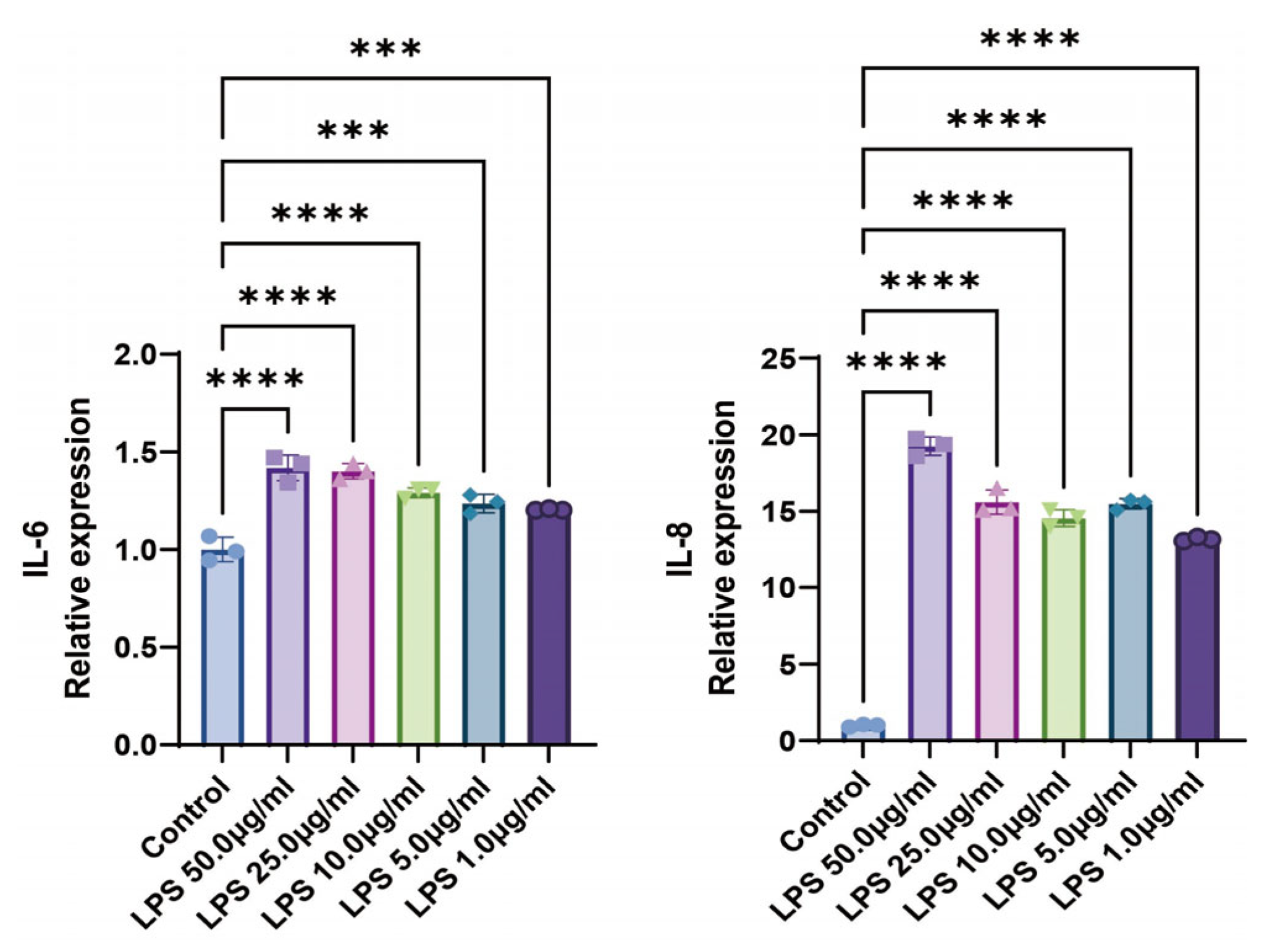

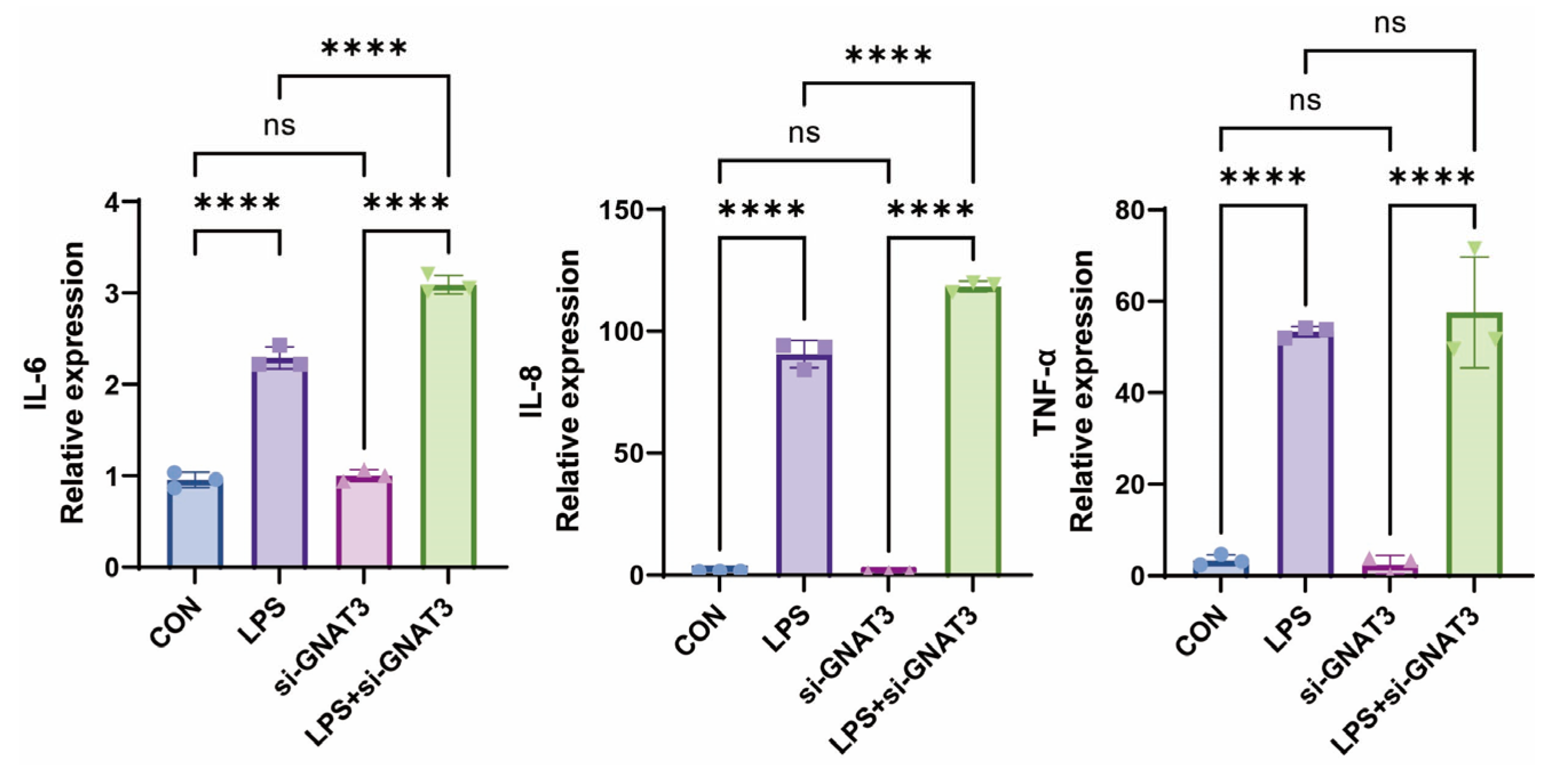

2.1. LPS Promotes the Expression Levels of Inflammatory Cytokines in BEAS-2B Cells

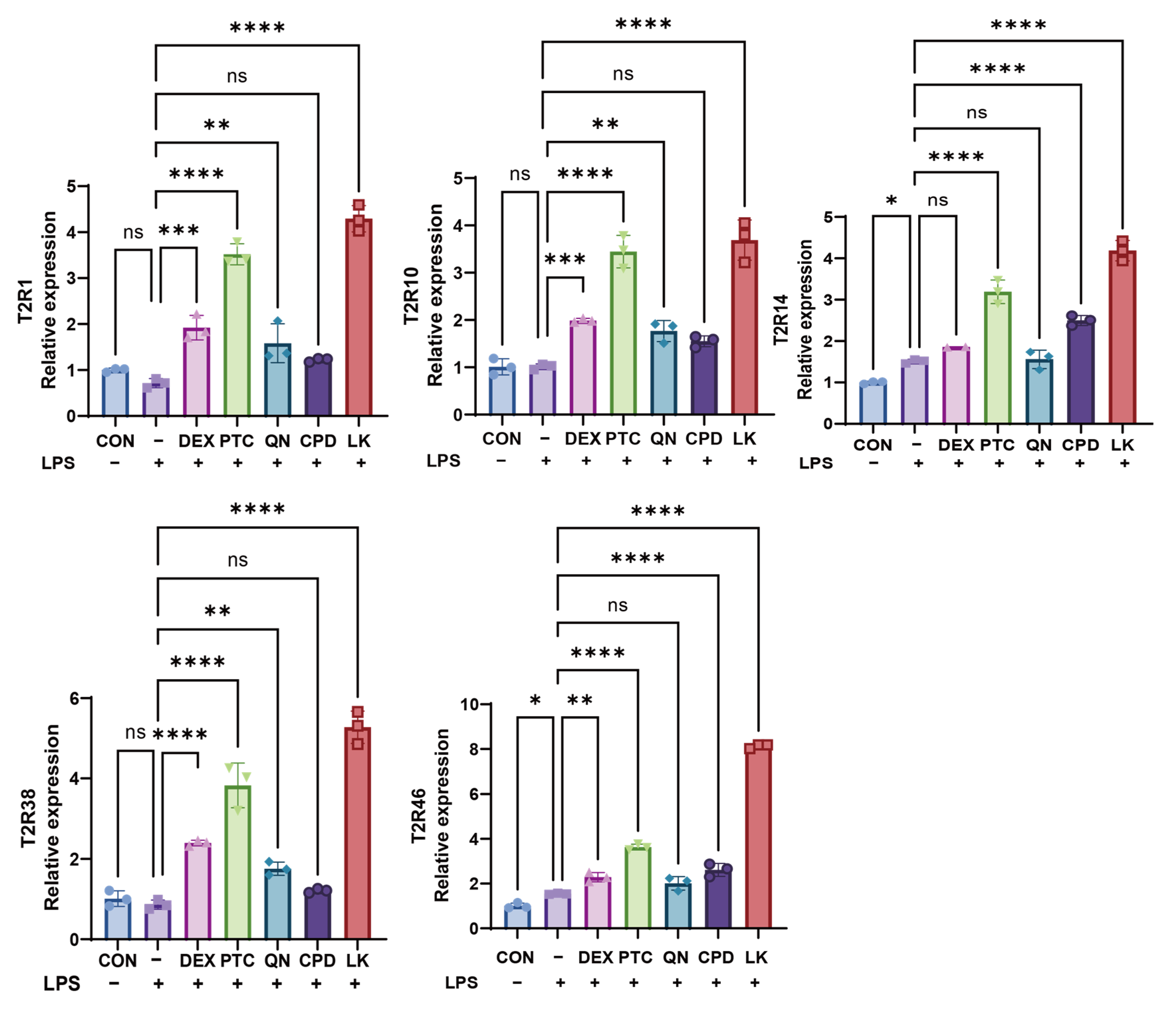

2.2. Bitter Receptor Agonists Specifically Upregulate Bitter Receptor Expression

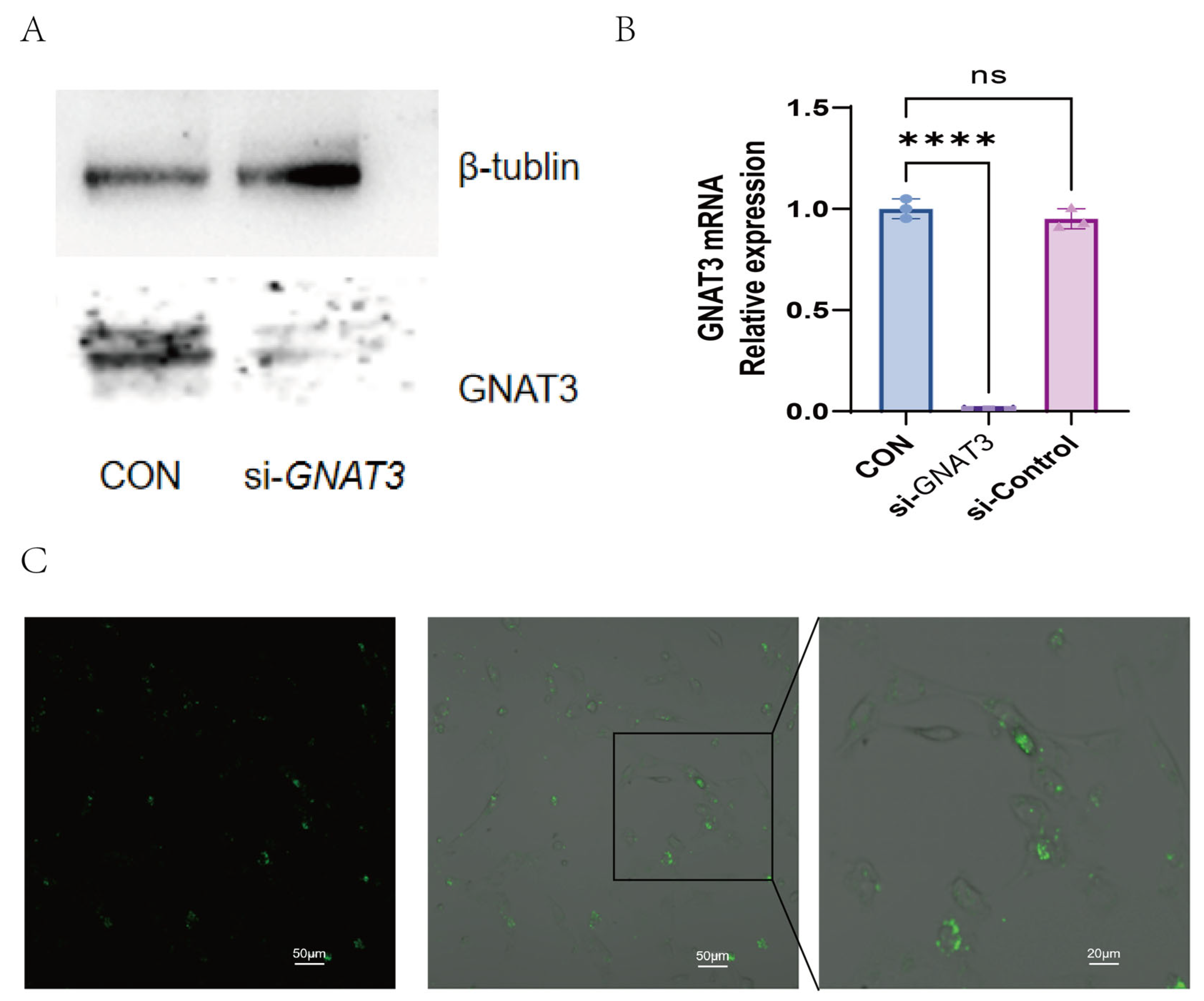

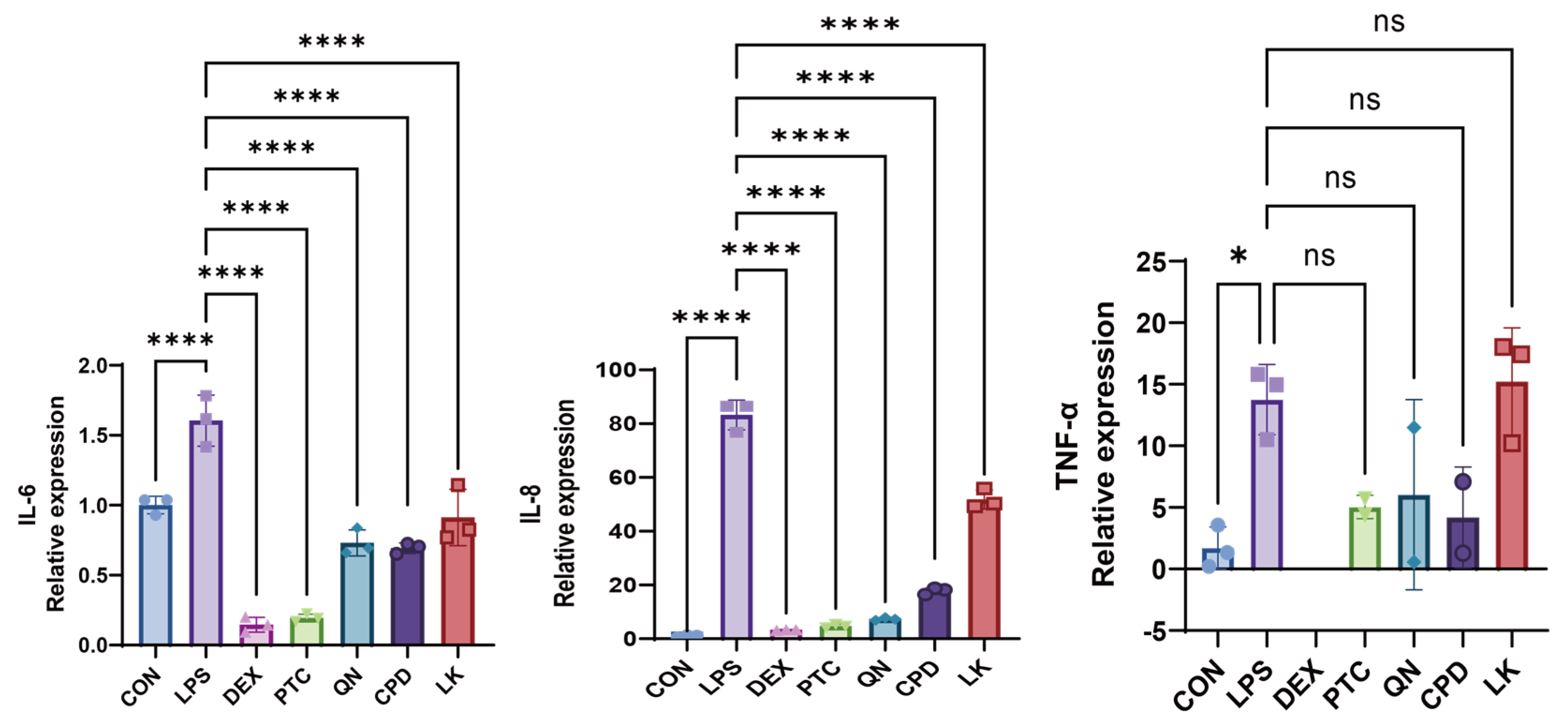

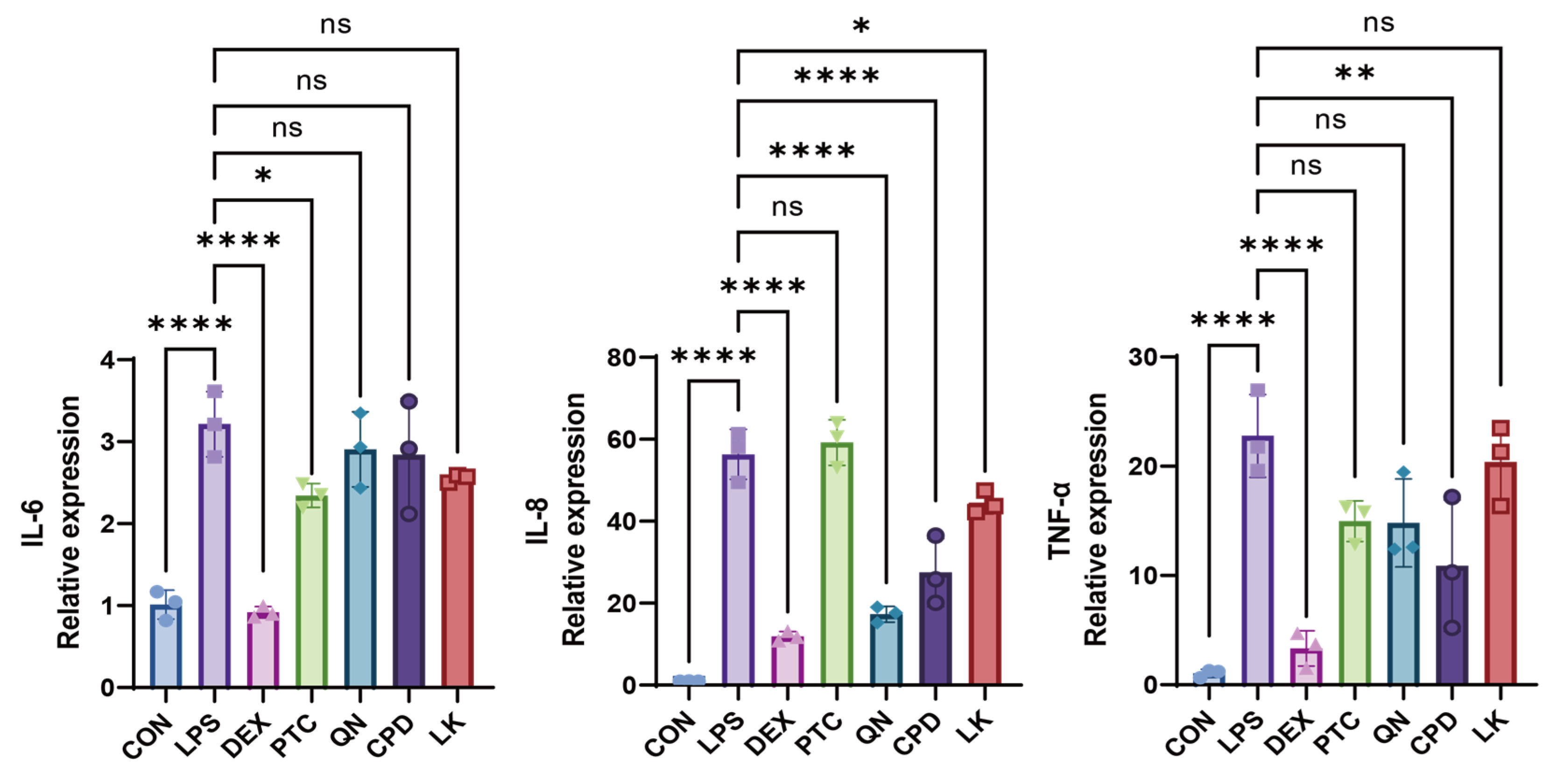

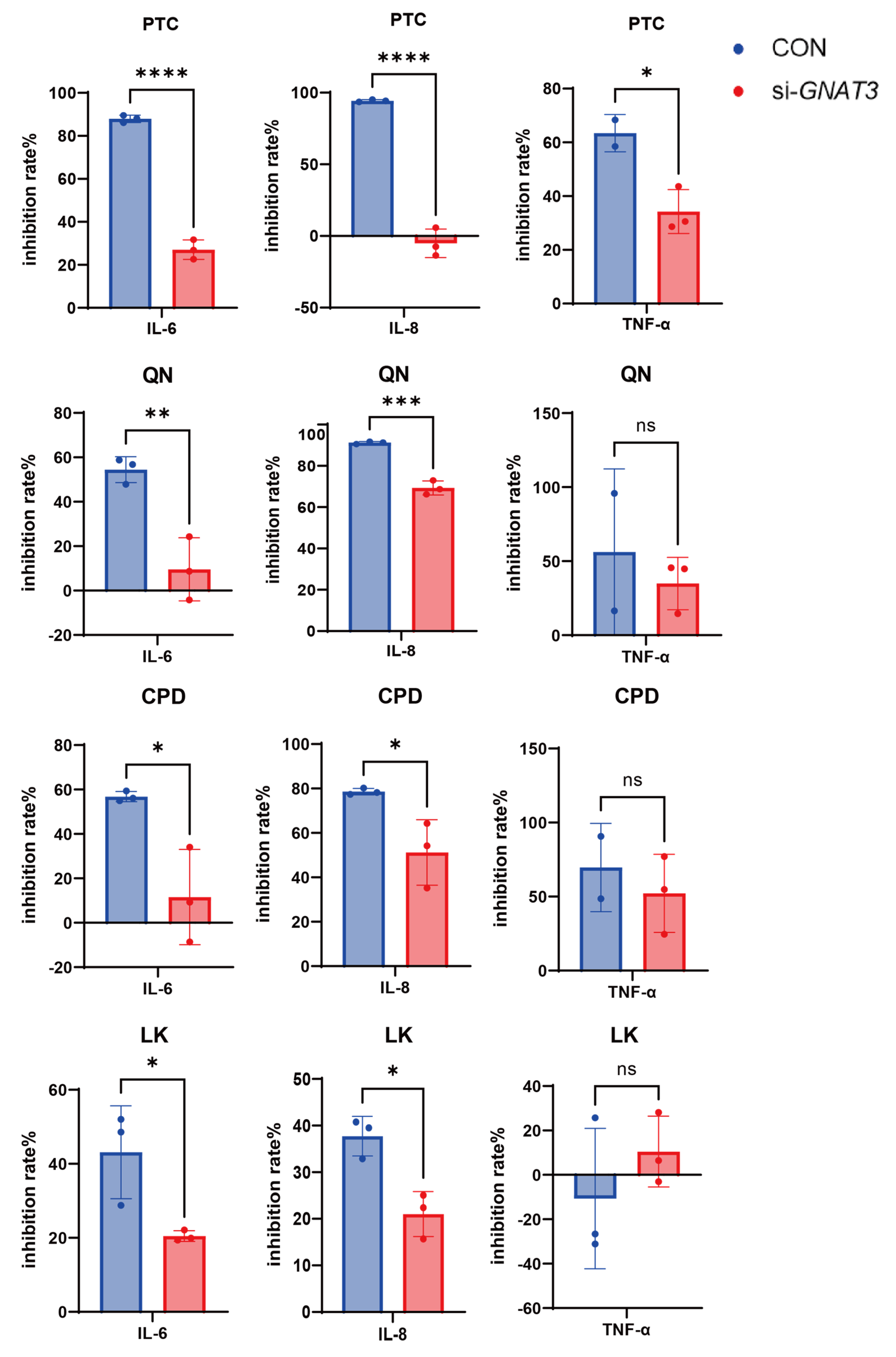

2.3. PTC, QN, CPD, and LK Regulate LPS-Induced Inflammatory Cytokine Expression in BEAS-2B Cells via GNAT3

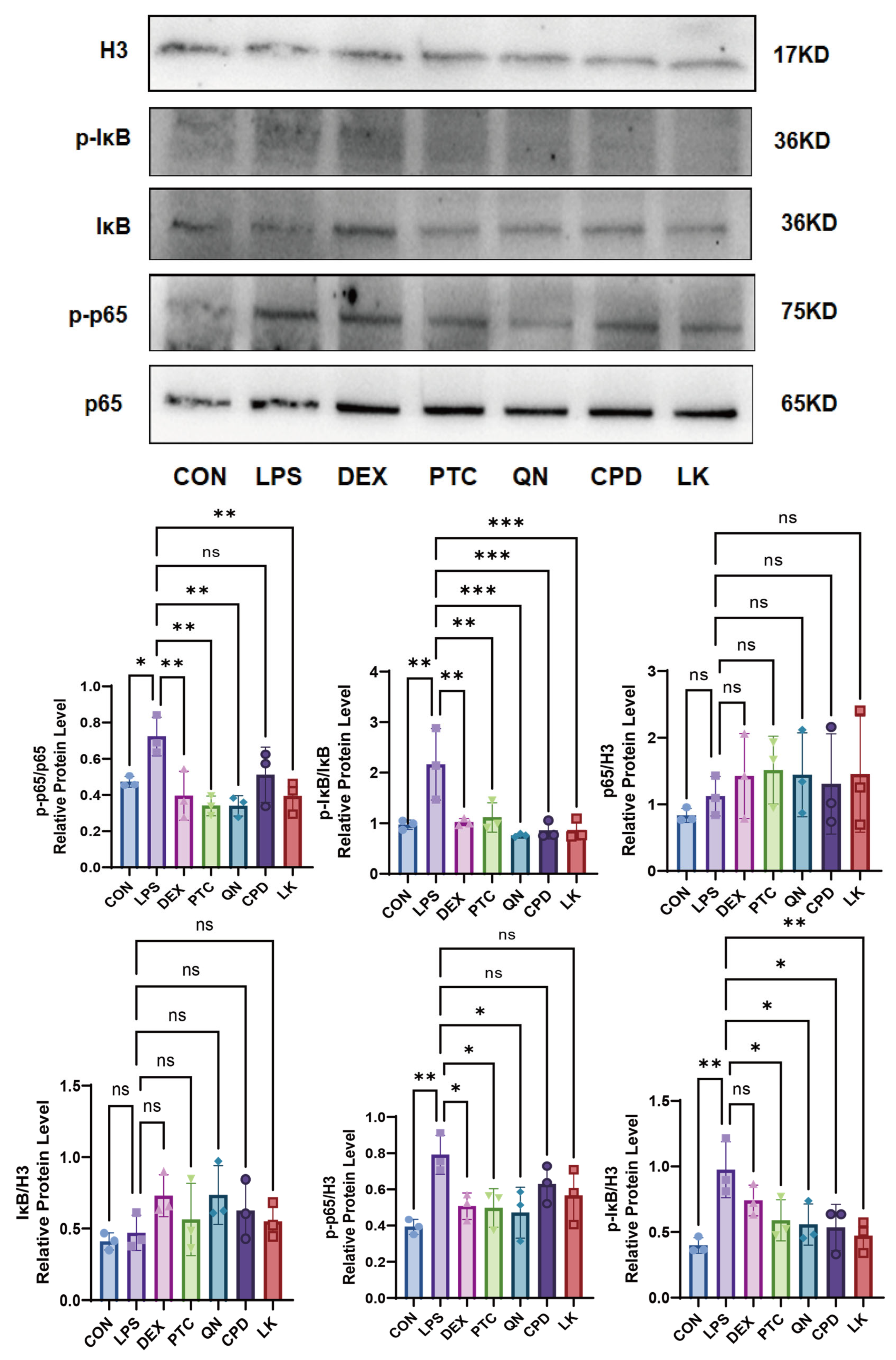

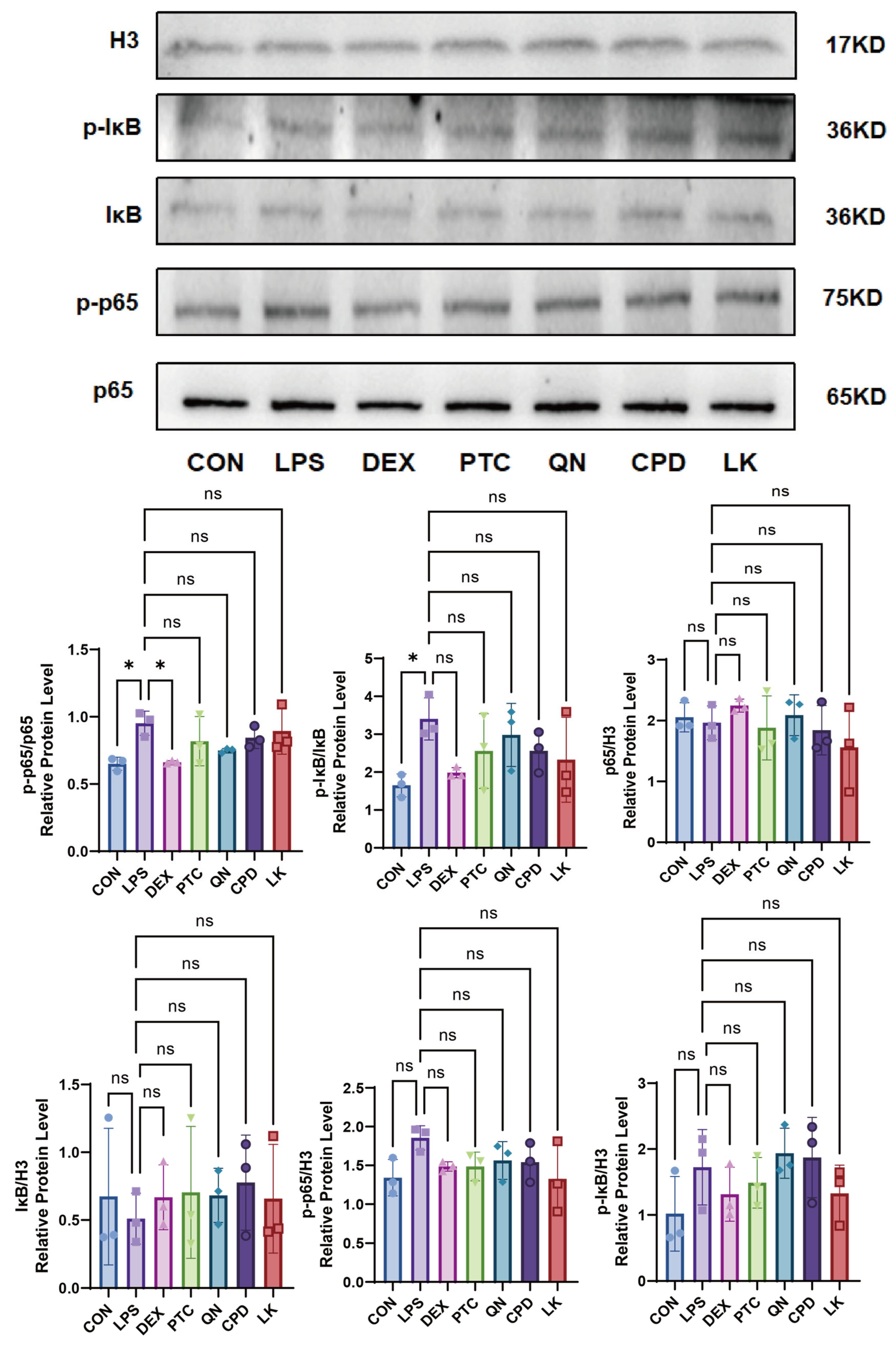

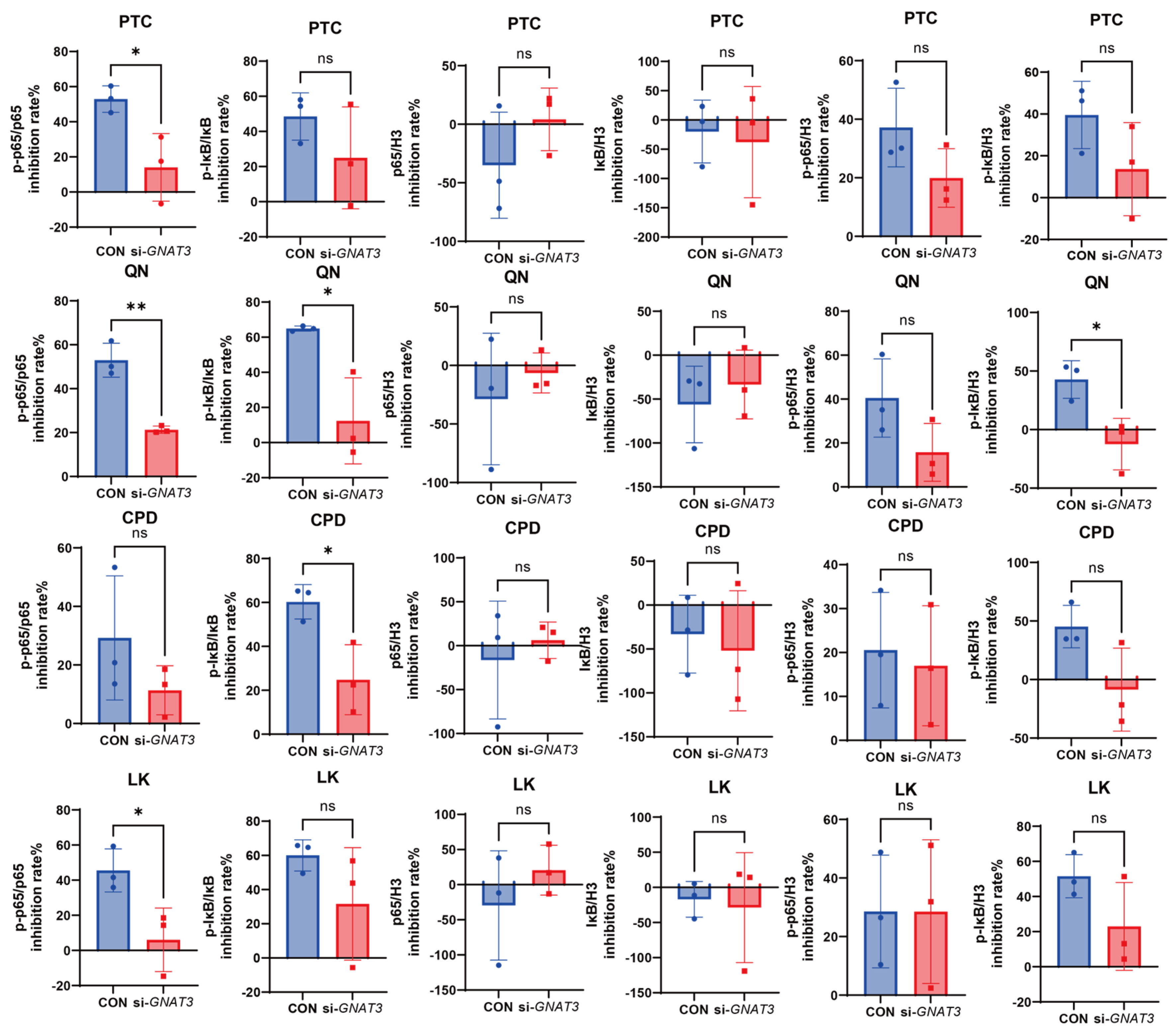

2.4. Effects of PTC, QN, CPD, and LK via GNAT3 on LPS-Induced NF-κB Pathway Protein Expression in BEAS-2B Cells

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture

4.2. Cell Viability Assay

4.3. Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR

4.4. Western Blot

4.5. siRNA Interference Experiment

4.6. Immunofluorescence

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| T2R | type 2 bitter taste receptor |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| DEX | Dexamethasone |

| PTC | Phenylthiourea |

| QN | Quinine |

| CPD | Carisoprodol |

| LK | Chloroquine |

References

- Yi, X.; Gao, J.; Wang, Z. The human lung microbiome—A hidden link between microbes and human health and diseases. Imeta 2022, 1, e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.K.; Kuckel, D.P.; Recidoro, A.M. Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Children: Rapid Evidence Review. Am. Fam. Physician 2021, 104, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Talmon, M.; Pollastro, F.; Fresu, L.G. The Complex Journey of the Calcium Regulation Downstream of TAS2R Activation. Cells 2022, 11, 3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, N.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Qin, Q.; Zhu, K.; Ren, X.; Chen, J. Progress of research on distribution and function of bitter taste receptors in oral cavity. Stomatology 2024, 44, 391–396. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, A.S.; Ben-Shahar, Y.; Moninger, T.O.; Kline, J.N.; Welsh, M.J. Motile cilia of human airway epithelia are chemosensory. Science 2009, 325, 1131–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Xia, Z.; Zhong, W.; Pei, J.; Huang, X.; Fu, X.; Liu, J. Advances in bitterness receptors T2Rs in different diseases. China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2024, 49, 4347–4358. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon, C.P.; Deng, D.; Breslin, P.A.S. Bitter Taste Receptors (T2Rs) are Sentinels that Coordinate Metabolic and Immunological Defense Responses. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2021, 20, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merigo, F.; Benati, D.; Tizzano, M.; Osculati, F.; Sbarbati, A. α-Gustducin immunoreactivity in the airways. Cell Tissue Res. 2005, 319, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, T.; Chen, X.; Xu, H.; Song, Y.; Wang, H.; Gao, Y.; Wang, J.; Du, R.; Lou, H.; Dong, T. Mitochondrial metabolism mediated macrophage polarization in chronic lung diseases. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 239, 108208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schleimer, R.P.; Kato, A.; Kern, R.; Kuperman, D.; Avila, P.C. Epithelium: At the interface of innate and adaptive immune responses. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2007, 120, 1279–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, A.; Schleimer, R.P. Beyond inflammation: Airway epithelial cells are at the interface of innate and adaptive immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2007, 19, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vareille, M.; Kieninger, E.; Edwards, M.R.; Regamey, N. The airway epithelium: Soldier in the fight against respiratory viruses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 24, 210–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuanming, L.F.B. Research progress on the role of NF-κB signaling pathway in acute lung injury and TCM intervention. China Pharm. 2025, 36, 1277–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Tully, J.E.; Nolin, J.D.; Guala, A.S.; Hoffman, S.M.; Roberson, E.C.; Lahue, K.G.; van der Velden, J.; Anathy, V.; Blackwell, T.S.; Janssen-Heininger, Y.M. Cooperation between classical and alternative NF-kappaB pathways regulates proinflammatory responses in epithelial cells. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2012, 47, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, W.; Zhang, B.; Liu, X.; Zhang, C.; Liu, J.; Miao, Q. Interleukin-33-Dependent Accumulation of Regulatory T Cells Mediates Pulmonary Epithelial Regeneration During Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 653803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kertesz, Z.; Harrington, E.O.; Braza, J.; Guarino, B.D.; Chichger, H. Agonists for Bitter Taste Receptors T2R10 and T2R38 Attenuate LPS-Induced Permeability of the Pulmonary Endothelium in vitro. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 794370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grassin-Delyle, S.; Salvator, H.; Mantov, N.; Abrial, C.; Brollo, M.; Faisy, C.; Naline, E.; Couderc, L.J.; Devillier, P. Bitter Taste Receptors (TAS2Rs) in Human Lung Macrophages: Receptor Expression and Inhibitory Effects of TAS2R Agonists. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.J.; Xiong, G.; Kofonow, J.M.; Chen, B.; Lysenko, A.; Jiang, P.; Abraham, V.; Doghramji, L.; Adappa, N.D.; Palmer, J.N.; et al. T2R38 taste receptor polymorphisms underlie susceptibility to upper respiratory infection. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 4145–4159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhyaya, J.D.; Chakraborty, R.; Shaik, F.A.; Jaggupilli, A.; Bhullar, R.P.; Chelikani, P. The Pharmacochaperone Activity of Quinine on Bitter Taste Receptors. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Forward Primer Sequence (5′→3′) | Reverse Primer Sequence (5′→3′) | |

|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | CTGCCTGCTGCACTTTGGAG | ACATGGGCTACAGGCTTGTCACT |

| GNAT3 | AGAGGACCAACGACAACTTTATG | AGCCGTTTTATTACCTCAGCC |

| T2R1 | CACCCGGCAAATGAGAAACA | GACAGGATAGACAGCAACGC |

| T2R10 | CAGAAGCTCATGTGAAGGCAAT | GGGATAGATGGCTGTGGTTGT |

| T2R14 | ATACCCTTTACTTTGTCCCTGGCA | TGACAGTGTGCTGCATCTTCT |

| T2R38 | GGGTGATGGTTTGTGTTGGG | CTTGTGGTCGGCTCTTACCT |

| T2R46 | AGTTCCCTTCACTCTGACCCT | GTGGACCTTCATGCTGGGAT |

| IL-6 | ACTCACCTCTTCAGAACGAATTG | CCATCTTTGGAAGGTTCAGGTTG |

| IL-8 | CACCGGAAGGAACCATCTCA | TTGGGGTGGAAAGGTTTGGA |

| ACTB | TGGCACCCAGCACAATGAA | CTAAGTCATAGTCCGCCTAGAAGCA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wu, S.; He, X.; Wang, S.; Ma, R.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y. Defining the Critical Role of α-Gustducin for NF-κB Inhibition and Anti-Inflammatory Signal Transduction by Bitter Agonists in Lung Epithelium. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 997. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020997

Fang Y, Wang Q, Wu S, He X, Wang S, Ma R, Zhao H, Zhao X, Wang X, Zhang Y. Defining the Critical Role of α-Gustducin for NF-κB Inhibition and Anti-Inflammatory Signal Transduction by Bitter Agonists in Lung Epithelium. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):997. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020997

Chicago/Turabian StyleFang, Yuzhen, Qiujie Wang, Shuobin Wu, Xinxiu He, Shengyu Wang, Ruonan Ma, Hao Zhao, Xiaoyi Zhao, Xing Wang, and Yuxin Zhang. 2026. "Defining the Critical Role of α-Gustducin for NF-κB Inhibition and Anti-Inflammatory Signal Transduction by Bitter Agonists in Lung Epithelium" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 997. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020997

APA StyleFang, Y., Wang, Q., Wu, S., He, X., Wang, S., Ma, R., Zhao, H., Zhao, X., Wang, X., & Zhang, Y. (2026). Defining the Critical Role of α-Gustducin for NF-κB Inhibition and Anti-Inflammatory Signal Transduction by Bitter Agonists in Lung Epithelium. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 997. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020997