Disulfiram/Copper Combined with Irradiation Induces Immunogenic Cell Death in Melanoma

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

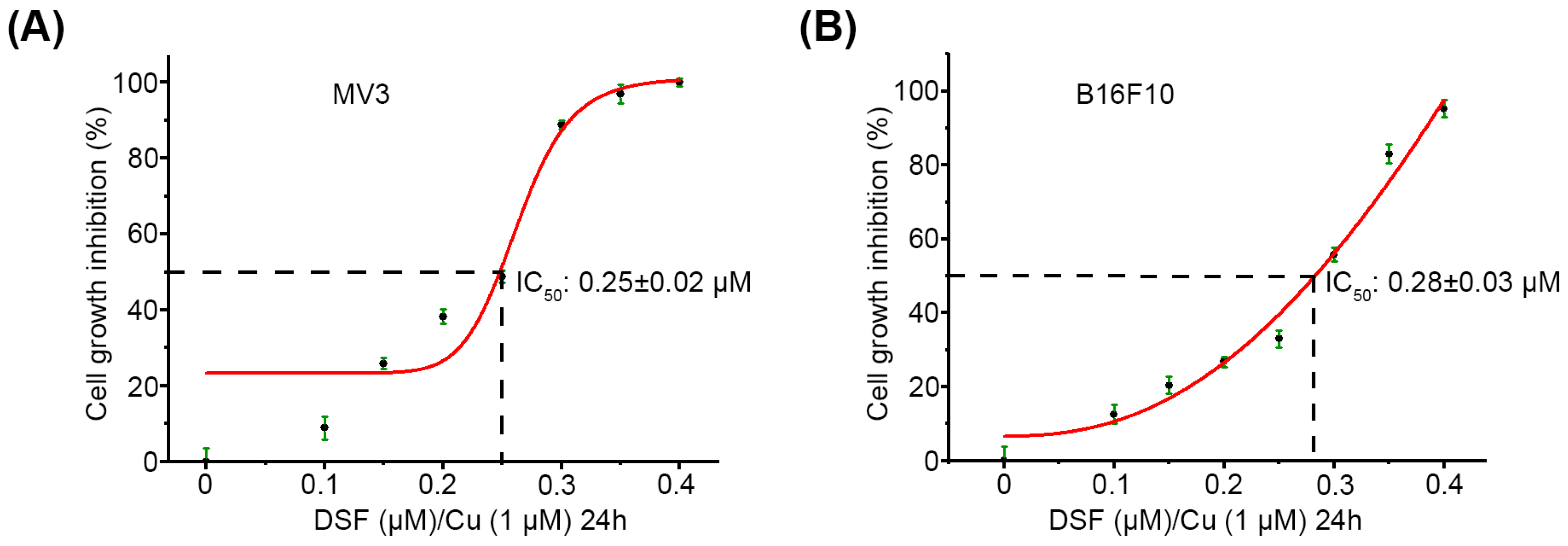

2.1. DSF/Cu Decreases Viability of Melanoma Cells In Vitro

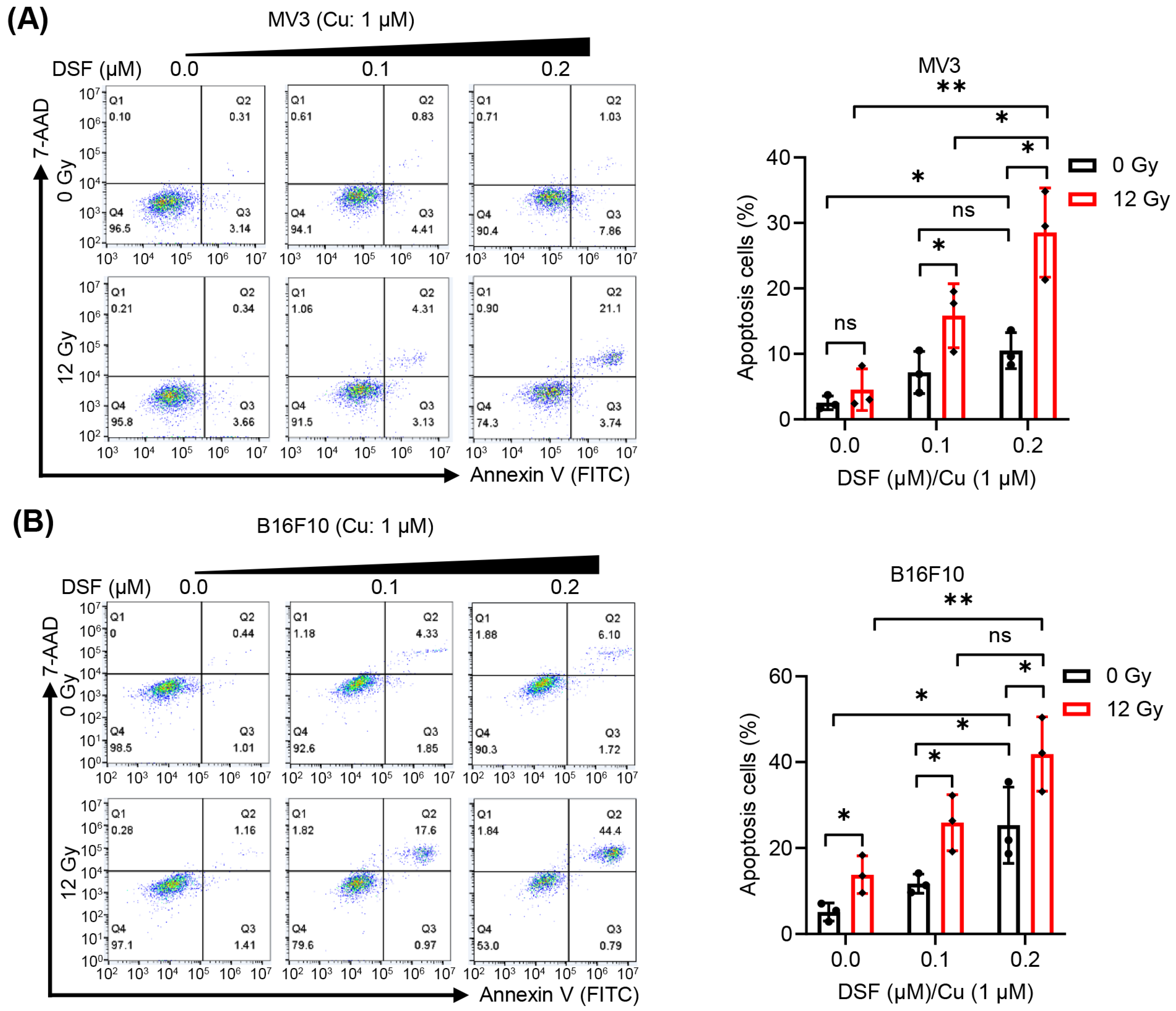

2.2. DSF/Cu + IR Induces Apoptosis of Melanoma Cells In Vitro

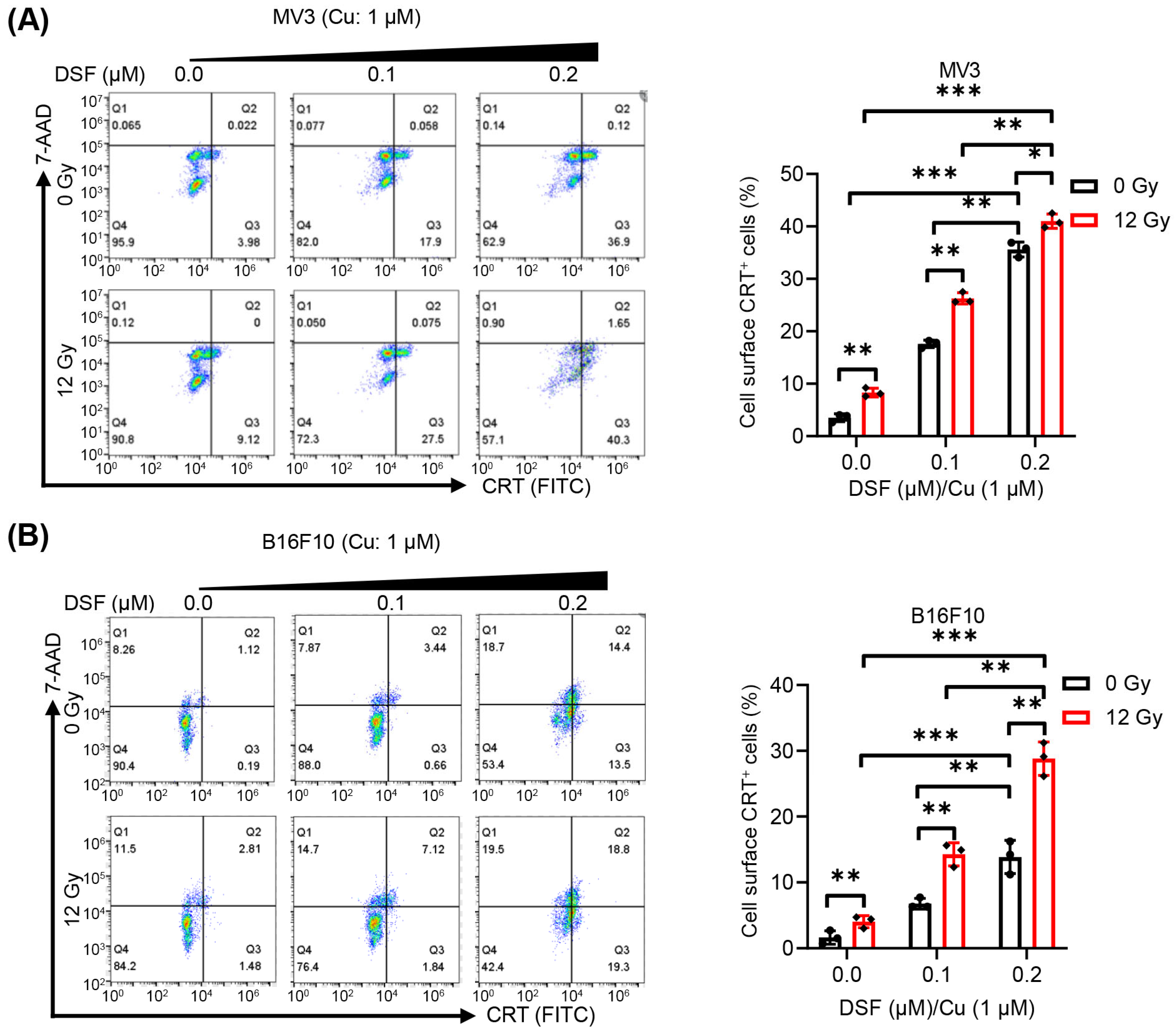

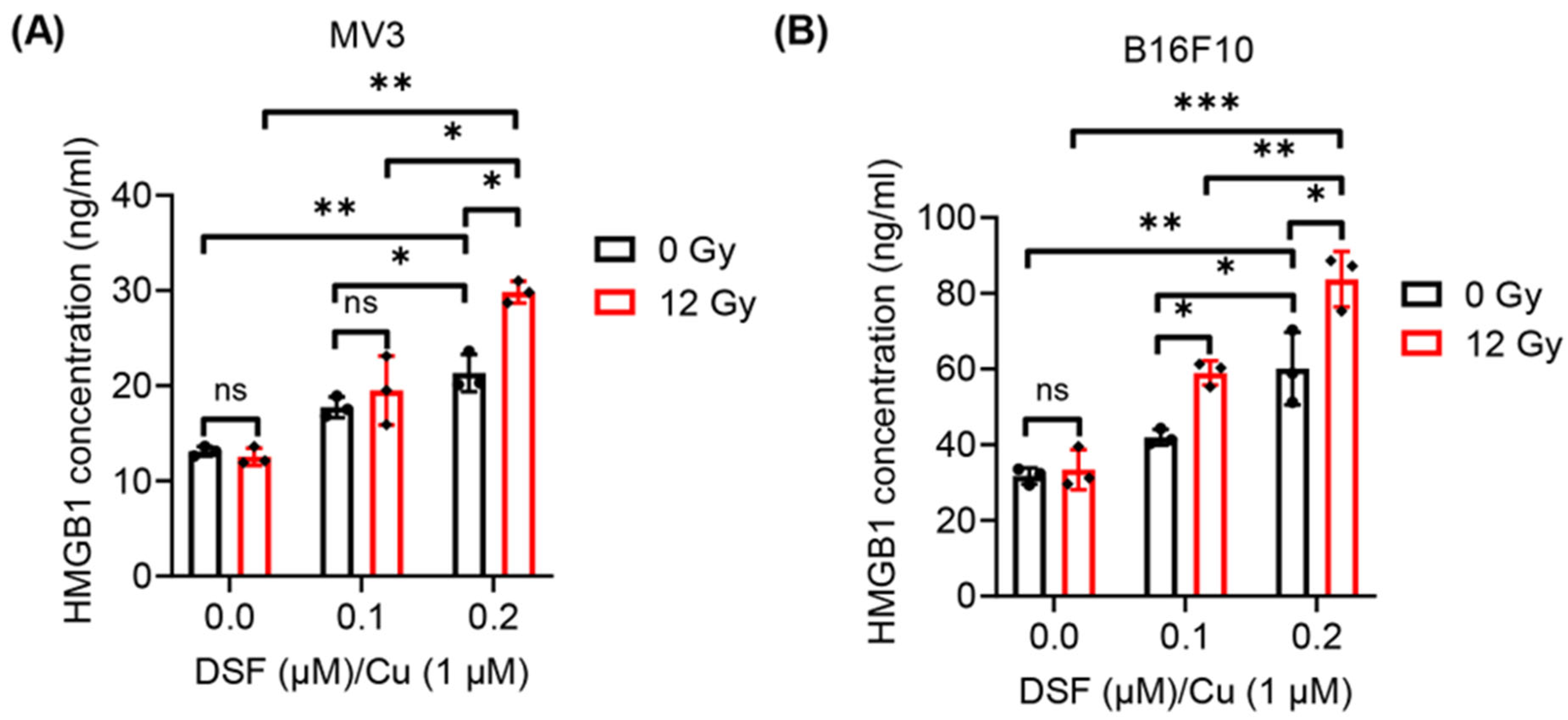

2.3. DSF/Cu + IR Induces ICD of Melanoma Cells In Vitro

2.4. Impact of DSF/Cu + IR on Tumor Growth in the Mouse B16F10 Melanoma Model

2.5. Levels of Distinct Subpopulations of Infiltrating Immune Cells in Tumors

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Lines

4.2. Chemical Reagents and X-Ray Machine

4.3. Cell Treatment DSF/Cu and/or IR In Vitro

4.4. Cell Viability Assay

4.5. Cell Apoptosis Assay

4.6. Flow Cytometric Analysis of Cell Surface Expression of CRT

4.7. Detection of Intracellular ATP

4.8. Quantitation of Extracellular HMGB1

4.9. Animals and Ethics Statement

4.10. Therapy of B16F10 Melanoma-Bearing C57BL/6 Mice

4.11. Preparation of a Single-Cell Suspension of Mouse Melanoma Tumor Tissue for Flow Cytometry Analyses

4.12. Characterization of Tumor-Infiltrating Immune Cells by Flow Cytometry Analysis

4.13. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wei, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, G.; Liu, M. Current landscape and future directions of bispecific antibodies in cancer immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1035276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, A.; Karapetyan, L.; Kirkwood, J.M. Immunotherapy in Melanoma: Recent Advances and Future Directions. Cancers 2023, 15, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorentino, V.; Pizzimenti, C.; Franchina, M.; Pepe, L.; Russotto, F.; Tralongo, P.; Micali, M.G.; Militi, G.B.; Lentini, M. Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1 Immunohistochemical Expression and Cutaneous Melanoma: A Controversial Relationship. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, E.; Schinzari, G.; Zizzari, I.G.; Maiorano, B.A.; Pagliara, M.M.; Sammarco, M.G.; Fiorentino, V.; Petrone, G.; Cassano, A.; Rindi, G.; et al. Immunological Backbone of Uveal Melanoma: Is There a Rationale for Immunotherapy? Cancers 2019, 11, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreidieh, F.Y.; Tawbi, H.A. The introduction of LAG-3 checkpoint blockade in melanoma: Immunotherapy landscape beyond PD-1 and CTLA-4 inhibition. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2023, 15, 17588359231186027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, B.M.; Fane, M.E.; Weeraratna, A.T.; Rebecca, V.W. Determinants of resistance and response to melanoma therapy. Nat. Cancer 2024, 5, 964–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Gomes, F.; Lorigan, P. The role for chemotherapy in the modern management of melanoma. Melanoma Manag. 2017, 4, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Zheng, M. Advances in targeted therapy and immunotherapy for melanoma (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2023, 26, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.B.; Sosman, J.A. Update on the targeted therapy of melanoma. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2013, 14, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrdinka, M.; Yabal, M. Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins in human health and disease. Genes Immun. 2019, 20, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogarty, G.B.; Hong, A. Radiation therapy for advanced and metastatic melanoma. J. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 109, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dousset, L.; Pacaud, A.; Barnetche, T.; Kostine, M.; Dutriaux, C.; Pham-Ledard, A.; Beylot-Barry, M.; Gerard, E.; Prey, S.; Andreu, N.; et al. Analysis of tumor response and clinical factors associated with vitiligo in patients receiving anti-programmed cell death-1 therapies for melanoma: A cross-sectional study. JAAD Int. 2021, 5, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badami, S.; Upadhaya, S.; Velagapudi, R.K.; Mikkilineni, P.; Kunwor, R.; Al Hadidi, S.; Bachuwa, G. Clinical and Molecular Characteristics Associated with Survival in Advanced Melanoma Treated with Checkpoint Inhibitors. J. Oncol. 2018, 2018, 6279871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cybulska-Stopa, B.; Rogala, P.; Czarnecka, A.M.; Lugowska, I.; Teterycz, P.; Galus, L.; Rajczykowski, M.; Dawidowska, A.; Piejko, K.; Suwinski, R.; et al. Efficacy of ipilimumab after anti-PD-1 therapy in sequential treatment of metastatic melanoma patients—Real world evidence. Adv. Med. Sci. 2020, 65, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhave, P.; Ahmed, T.; Lo, S.N.; Shoushtari, A.; Zaremba, A.; Versluis, J.M.; Mangana, J.; Weichenthal, M.; Si, L.; Lesimple, T.; et al. Efficacy of anti-PD-1 and ipilimumab alone or in combination in acral melanoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e004668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knispel, S.; Gassenmaier, M.; Menzies, A.M.; Loquai, C.; Johnson, D.B.; Franklin, C.; Gutzmer, R.; Hassel, J.C.; Weishaupt, C.; Eigentler, T.; et al. Outcome of melanoma patients with elevated LDH treated with first-line targeted therapy or PD-1-based immune checkpoint inhibition. Eur. J. Cancer 2021, 148, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzi, L.; Buque, A.; Kepp, O.; Zitvogel, L.; Kroemer, G. Immunogenic cell death in cancer and infectious disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, B. A review of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of disulfiram and its metabolites. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. Suppl. 1992, 369, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Cui, Q.C.; Yang, H.; Dou, Q.P. Disulfiram, a clinically used anti-alcoholism drug and copper-binding agent, induces apoptotic cell death in breast cancer cultures and xenografts via inhibition of the proteasome activity. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 10425–10433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doytcheva, M.A.; Jeliazkova, B.G. Structure of copper(II) dithiocarbamate mixed-ligand complexes and their photoreactivities in alcohols. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2004, 60, 1299–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cen, D.; Brayton, D.; Shahandeh, B.; Meyskens, F.L., Jr.; Farmer, P.J. Disulfiram facilitates intracellular Cu uptake and induces apoptosis in human melanoma cells. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 6914–6920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrott, Z.; Mistrik, M.; Andersen, K.K.; Friis, S.; Majera, D.; Gursky, J.; Ozdian, T.; Bartkova, J.; Turi, Z.; Moudry, P.; et al. Alcohol-abuse drug disulfiram targets cancer via p97 segregase adaptor NPL4. Nature 2017, 552, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, N.C.; Fombon, I.S.; Liu, P.; Brown, S.; Kannappan, V.; Armesilla, A.L.; Xu, B.; Cassidy, J.; Darling, J.L.; Wang, W. Disulfiram modulated ROS-MAPK and NFkappaB pathways and targeted breast cancer cells with cancer stem cell-like properties. Br. J. Cancer 2011, 104, 1564–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, P.; Ding, S.Y.; Sun, T.; Liu, L.; Han, S.; DeLeo, A.B.; Sadagopan, A.; Guo, W.; Wang, X. Induction of autophagy-dependent apoptosis in cancer cells through activation of ER stress: An uncovered anti-cancer mechanism by anti-alcoholism drug disulfiram. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2019, 9, 1266–1281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.; Yang, W.; Toprani, S.M.; Guo, W.; He, L.; DeLeo, A.B.; Ferrone, S.; Zhang, G.; Wang, E.; Lin, Z.; et al. Induction of immunogenic cell death in radiation-resistant breast cancer stem cells by repurposing anti-alcoholism drug disulfiram. Correction in Cell Commun. Signal. 2020, 18, 36. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Drum, D.L.; Sun, R.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, F.; Sun, F.; Dal, E.; Yu, L.; Jia, J.; Arya, S.; et al. Stressed target cancer cells drive nongenetic reprogramming of CAR T cells and solid tumor microenvironment. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Qian, Y.; Wei, J.; Jin, T.; Kong, X.; Cao, H.; Ding, K. The Disulfiram/Copper Complex Induces Autophagic Cell Death in Colorectal Cancer by Targeting ULK1. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 752825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, F.; Chen, J.; Chan, S.; He, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, G. Disulfiram/Copper Induces Antitumor Activity against Both Nasopharyngeal Cancer Cells and Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts through ROS/MAPK and Ferroptosis Pathways. Cancers 2020, 12, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, L.H.; Zhang, H.T.; Wang, Y.T.; Liu, S.; Zhou, W.L.; Yuan, X.Z.; Li, T.Y.; Wu, C.F.; Yang, J.Y. Disulfiram combined with copper inhibits metastasis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma through the NF-kappaB and TGF-beta pathways. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2018, 22, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, W.; Yang, C.; Jing, Q.; Zhou, C.; Wang, X.; Hu, J.; Wang, L.; et al. Overcoming the compensatory elevation of NRF2 renders hepatocellular carcinoma cells more vulnerable to disulfiram/copper-induced ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 2021, 46, 102122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.; Tait, S.W.G. Targeting immunogenic cell death in cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2020, 14, 2994–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohles, N.; Nagel, D.; Jungst, D.; Stieber, P.; Holdenrieder, S. Predictive value of immunogenic cell death biomarkers HMGB1, sRAGE, and DNase in liver cancer patients receiving transarterial chemoembolization therapy. Tumour Biol. 2012, 33, 2401–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, I.; Wang, Y.; Michaud, M.; Ma, Y.; Sukkurwala, A.Q.; Shen, S.; Kepp, O.; Metivier, D.; Galluzzi, L.; Perfettini, J.L.; et al. Molecular mechanisms of ATP secretion during immunogenic cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2014, 21, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, M.; Tesniere, A.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Fimia, G.M.; Apetoh, L.; Perfettini, J.L.; Castedo, M.; Mignot, G.; Panaretakis, T.; Casares, N.; et al. Calreticulin exposure dictates the immunogenicity of cancer cell death. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesniere, A.; Panaretakis, T.; Kepp, O.; Apetoh, L.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Zitvogel, L.; Kroemer, G. Molecular characteristics of immunogenic cancer cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2008, 15, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broz, P.; Monack, D.M. Newly described pattern recognition receptors team up against intracellular pathogens. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Jia, L.; Xie, L.; Kiang, J.G.; Wang, Y.; Sun, F.; Lin, Z.; Wang, E.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, P.; et al. Turning anecdotal irradiation-induced anticancer immune responses into reproducible in situ cancer vaccines via disulfiram/copper-mediated enhanced immunogenic cell death of breast cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, B.; Zhu, S. Disulfiram/Copper Activates ER Stress to Promote Immunogenic Cell Death of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2024, 82, 1291–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Guo, Q.; Fu, H.; Yu, J.; Wang, L.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; Duan, Y. Asynchronous blockade of PD-L1 and CD155 by polymeric nanoparticles inhibits triple-negative breast cancer progression and metastasis. Biomaterials 2021, 275, 120988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, A.C.; Zappasodi, R. A decade of checkpoint blockade immunotherapy in melanoma: Understanding the molecular basis for immune sensitivity and resistance. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 660–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Chen, J.; Zhao, L.; Hollebecque, A.; Kepp, O.; Zitvogel, L.; Kroemer, G. PD-1 blockade synergizes with oxaliplatin-based, but not cisplatin-based, chemotherapy of gastric cancer. Oncoimmunology 2022, 11, 2093518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, R.; Dawulieti, J.; Chi, N.; Wu, Z.; Yun, Z.; Du, J.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Xie, X.; Xiao, K.; et al. Self-polymerized platinum (II)-Polydopamine nanomedicines for photo-chemotherapy of bladder Cancer favoring antitumor immune responses. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogino, T.; Wang, X.; Kato, S.; Miyokawa, N.; Harabuchi, Y.; Ferrone, S. Endoplasmic reticulum chaperone-specific monoclonal antibodies for flow cytometry and immunohistochemical staining. Tissue Antigens 2003, 62, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroemer, G.; Galassi, C.; Zitvogel, L.; Galluzzi, L. Immunogenic cell stress and death. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 487–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fucikova, J.; Kepp, O.; Kasikova, L.; Petroni, G.; Yamazaki, T.; Liu, P.; Zhao, L.; Spisek, R.; Kroemer, G.; Galluzzi, L. Detection of immunogenic cell death and its relevance for cancer therapy. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasikova, L.; Hensler, M.; Truxova, I.; Skapa, P.; Laco, J.; Belicova, L.; Praznovec, I.; Vosahlikova, S.; Halaska, M.J.; Brtnicky, T.; et al. Calreticulin exposure correlates with robust adaptive antitumor immunity and favorable prognosis in ovarian carcinoma patients. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysko, D.V.; Agostinis, P.; Krysko, O.; Garg, A.D.; Bachert, C.; Lambrecht, B.N.; Vandenabeele, P. Emerging role of damage-associated molecular patterns derived from mitochondria in inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2011, 32, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, M.R.; Chekeni, F.B.; Trampont, P.C.; Lazarowski, E.R.; Kadl, A.; Walk, S.F.; Park, D.; Woodson, R.I.; Ostankovich, M.; Sharma, P.; et al. Nucleotides released by apoptotic cells act as a find-me signal to promote phagocytic clearance. Nature 2009, 461, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, M.; Shin, J.; Lee, C.E.; Chung, J.Y.; Kim, M.; Yan, X.; Yang, W.H.; Cha, J.H. Immunogenic cell death in cancer immunotherapy. BMB Rep. 2023, 56, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Guo, L.; Zhang, B.; Liu, S.; Zhang, K.; Yan, J.; Zhang, W.; Yu, M.; Chen, Z.; Xu, Y.; et al. Disulfiram combined with copper induces immunosuppression via PD-L1 stabilization in hepatocellular carcinoma. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2019, 9, 2442–2455. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yuan, M.; Shi, L.; Liu, Y.; Xiang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Ji, M.; Hou, P. Disulfiram/copper triggers cGAS-STING innate immunity pathway via ROS-induced DNA damage that potentiates antitumor response to PD-1 checkpoint blockade. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2025, 21, 1730–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medetgul-Ernar, K.; Davis, M.M. Standing on the shoulders of mice. Immunity 2022, 55, 1343–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pangrsic, T.; Potokar, M.; Stenovec, M.; Kreft, M.; Fabbretti, E.; Nistri, A.; Pryazhnikov, E.; Khiroug, L.; Giniatullin, R.; Zorec, R. Exocytotic release of ATP from cultured astrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 28749–28758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, J.; Kunda, N.; Qiao, G.; Calata, J.F.; Pardiwala, K.; Prabhakar, B.S.; Maker, A.V. Colon cancer cell treatment with rose bengal generates a protective immune response via immunogenic cell death. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, E.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, L.; Lin, Z.; Sun, T.; Hu, P.; Wang, K.; Shang, Z.; Guo, W.; Kiang, J.G.; et al. Disulfiram/Copper Combined with Irradiation Induces Immunogenic Cell Death in Melanoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 980. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020980

Wang E, Zhang Y, Jia L, Lin Z, Sun T, Hu P, Wang K, Shang Z, Guo W, Kiang JG, et al. Disulfiram/Copper Combined with Irradiation Induces Immunogenic Cell Death in Melanoma. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):980. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020980

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Enwen, Yida Zhang, Lin Jia, Zunwen Lin, Ting Sun, Pan Hu, Kun Wang, Zikun Shang, Wei Guo, Juliann G. Kiang, and et al. 2026. "Disulfiram/Copper Combined with Irradiation Induces Immunogenic Cell Death in Melanoma" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 980. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020980

APA StyleWang, E., Zhang, Y., Jia, L., Lin, Z., Sun, T., Hu, P., Wang, K., Shang, Z., Guo, W., Kiang, J. G., & Wang, X. (2026). Disulfiram/Copper Combined with Irradiation Induces Immunogenic Cell Death in Melanoma. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 980. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020980