Profiles of Growth Factors Secreted by In Vitro-Stimulated Paediatric Acute Leukaemia Blasts of Myeloid and Lymphoid Origin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

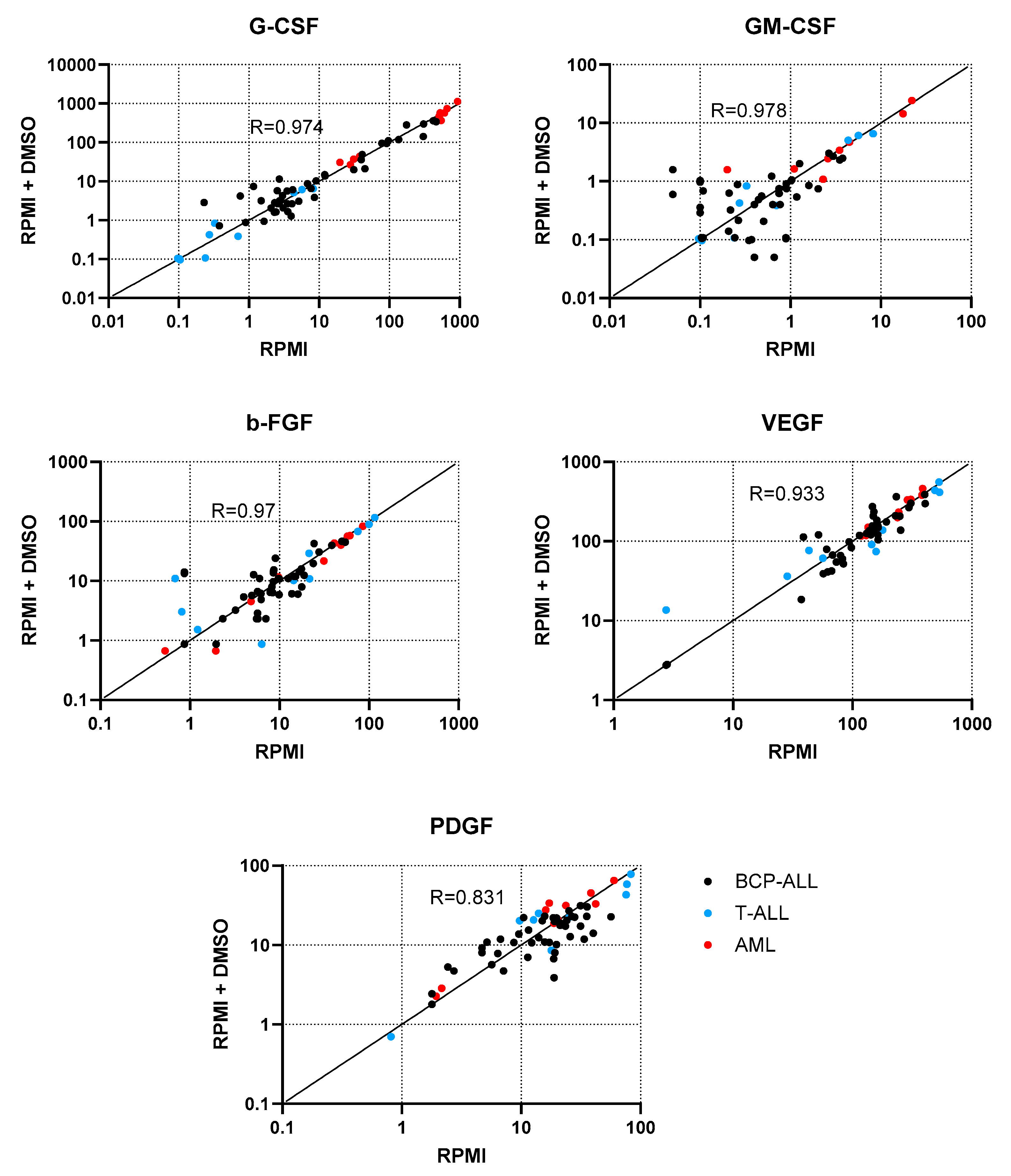

2.1. Determination of the Influence of the Dissolvent on Cell Stimulation

2.2. Basal Concentrations of the Examined GF

2.3. Response of Leukaemic Cells to Stimulation

2.3.1. G-CSF

2.3.2. GM-CSF

2.3.3. b-FGF

2.3.4. VEGF

2.3.5. PDGF

2.4. Lineage-Specific Responses to Stimulation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patients

4.2. Leukaemic Cell Enrichment

4.3. Cell Stimulation

4.4. Growth Factor (GF) Immunoassay

4.5. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GF | Growth factor |

| BCP-ALL | B-cell precursor and T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia |

| T-ALL | T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia |

| PHA | phytohemagglutinin |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| AML | acute myeloid leukaemia |

| PMA + I | phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate with ionophore A23187 |

| GM-CSF | granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| G-CSF | granulocyte colony-stimulating factor |

| b-FGF | basic fibroblast growth factor |

| VEGF | vascular endothelial growth factor |

| PDGF | platelet-derived growth factor |

| MNC | mononuclear cell |

| DMSO | dimethyl sulfoxide |

| CNSL | central nervous system localisation |

| CSF | cerebrospinal fluid |

References

- Wachter, F.; Pikman, Y. Pathophysiology of Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Acta Haematol. 2024, 147, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.H.-C.; Poppe, M.M.; Hua, C.-H.; Marcus, K.J.; Esiashvili, N. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2021, 68, e28371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Coleman, M.P. Increasing incidence of childhood leukaemia: A controversy re-examined. Br. J. Cancer 2007, 97, 1009–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 12–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micallef, B.; Nisticò, R.; Sarac, S.B.; Bjerrum, O.W.; Butler, D.; Sammut Bartolo, N.; Serracino-Inglott, A.; Borg, J.J. The changing landscape of treatment options in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Drug Discov. Today 2022, 27, 1483–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Hu, B.; Zhang, J. Epidemiological characteristics and influencing factors of acute leukemia in children and adolescents and adults: A large population-based study. Hematology 2024, 29, 2327916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães-Gama, F.; Kerr, M.W.A.; de Araújo, N.D.; Ibiapina, H.N.S.; Neves, J.C.F.; Hanna, F.S.A.; Xabregas, L.d.A.; Carvalho, M.P.S.S.; Alves, E.B.; Tarragô, A.M.; et al. Imbalance of Chemokines and Cytokines in the Bone Marrow Microenvironment of Children with B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. J. Oncol. 2021, 2021, 5530650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, T.P.; Wiemels, J.L.; Zhou, M.; Kang, A.Y.; McCoy, L.S.; Wang, R.; Fitch, B.; Petrick, L.M.; Yano, Y.; Imani, P.; et al. Cytokine Levels at Birth in Children Who Developed Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2021, 30, 1526–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solati, H.; Zareinejad, M.; Ghavami, A.; Ghasemi, Z.; Amirghofran, Z. IL-35 and IL-18 Serum Levels in Children with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: The Relationship with Prognostic Factors. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 42, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampogiannis, A.; Piperi, C.; Baka, M.; Zoi, I.; Papavassiliou, A.G.; Moschovi, M. Low IL-23 levels in peripheral blood and bone marrow at diagnosis of acute leukemia in children increased with the elimination of leukemic burden. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 7426–7435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, M.; Monteiro, A.C.; Neto, E.; Barrias, C.C.; Sobrinho-Simões, M.A.; Duarte, D.; Caires, H.R. Transforming the niche: The emerging role of extracellular vesicles in acute myeloid leukaemia progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Garcia, M.; Weng, L.; Jung, X.; Murakami, J.L.; Hu, X.; McDonald, T.; Lin, A.; Kumar, A.R.; DiGiusto, D.L.; et al. Acute myeloid leukemia transforms the bone marrow niche into a leukemia-permissive microenvironment through exosome secretion. Leukemia 2017, 32, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Q.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Y.; Ye, L.; Shi, R.; Peng, L.; Guo, S.; He, J.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Cytokine network imbalance in children with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia at diagnosis. Cytokine 2023, 169, 156267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, M.P.S.S.; Magalhães-Gama, F.; Loiola, B.P.; Neves, J.C.F.; Araújo, N.D.; Silva, F.S.; Catão, C.L.S.; Alves, E.B.; Pimentel, J.P.D.; Barbosa, M.N.S.; et al. Systemic immunological profile of children with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Performance of cell populations and soluble mediators as serum biomarkers. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1290505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-L.; Tang, C.; Zhang, M.-Y.; Huang, W.-L.; Xu, Y.; Sun, H.-Y.; Yang, F.; Song, L.-L.; Wang, H.; Mu, L.-L.; et al. Blocking ATM-dependent NF-κB pathway overcomes niche protection and improves chemotherapy response in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 2019, 33, 2365–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Witkowski, M.T.; Harris, J.; Dolgalev, I.; Sreeram, S.; Qian, W.; Tong, J.; Chen, X.; Aifantis, I.; Chen, W. Leukemia-on-a-chip: Dissecting the chemoresistance mechanisms in B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia bone marrow niche. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba5536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, B.S.; Slone, W.L.; Thomas, P.; Evans, R.; Piktel, D.; Angel, P.M.; Walsh, C.M.; Cantrell, P.S.; Rellick, S.L.; Martin, K.H.; et al. Bone marrow microenvironment modulation of acute lymphoblastic leukemia phenotype. Exp. Hematol. 2016, 44, 50–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenjen, N.; Ersvær, E.; Ryningen, A.; Bruserud, Ø. In vitro effects of native human acute myelogenous leukemia blasts on fibroblasts and osteoblasts. Int. J. Cancer 2004, 111, 858–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dander, E.; Palmi, C.; D’Amico, G.; Cazzaniga, G. The bone marrow niche in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: The role of microenvironment from pre-leukemia to overt leukemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennis, S.; Conforte, A.; O’Reilly, E.; Takanlu, J.S.; Cichocka, T.; Dhami, S.P.; Nicholson, P.; Krebs, P.; Ó Broin, P.; Szegezdi, E. Cell-cell interactome of the hematopoietic niche and its changes in acute myeloid leukemia. iScience 2023, 26, 106943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankfurt, O.; Tallman, M.S. Growth factors in leukemia. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2007, 5, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, K.; Song, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, X.; Fu, Y.; Yu, F.; Zhou, H.; Liu, X.; Zhou, J.; Fang, B. Efficacy and safety of G-CSF, low-dose cytarabine and aclarubicin in combination with l-asparaginase, prednisone in the treatment of refractory or relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk. Res. 2017, 62, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallerfors, B.; Olofsson, T.; Lenhoff, S. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) in serum in bone marrow transplanted patients. Bone Marrow Transpl. 1991, 8, 191–195. [Google Scholar]

- Beekman, R.; Touw, I.P. G-CSF and its receptor in myeloid malignancy. Blood 2010, 115, 5131–5136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzanotte, V.; Paterno, G.; Cerroni, I.; De Marchi, L.; Taka, K.; Buzzatti, E.; Mallegni, F.; Meddi, E.; Moretti, F.; Buccisano, F.; et al. Use of Primary Prophylaxis with G-CSF in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Patients Undergoing Intensive Chemotherapy Does Not Affect Quality of Response. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nara, N.; Kurokawa, H.; Tohda, S.; Tomiyama, J.; Nagata, K.; Tanikawa, S. The effect of basic and acidic fibroblast growth factors (bFGF and aFGF) on the growth of leukemic blast progenitors in acute myelogenous leukemia. Exp. Hematol. 1995, 23, 1030–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, B.; Ulvestad, E.; Bruserud, Ø. Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) in human acute myelogenous leukemia: PDGF receptor expression, endogenous PDGF release and responsiveness to exogenous PDGF isoforms by in vitro cultured acute myelogenous leukemia blasts. Eur. J. Haematol. 2001, 67, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egyed, B.; Horváth, A.; Semsei, Á.F.; Szalai, C.; Müller, J.; Erdélyi, D.J.; Kovács, G.T. Co-Detection of VEGF-A and Its Regulator, microRNA-181a, May Indicate Central Nervous System Involvement in Pediatric Leukemia. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2022, 28, 1610096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhael, N.L.; Gendi, M.A.S.H.; Hassab, H.; A Megahed, E. Evaluation of multiplexed biomarkers in assessment of CSF infiltration in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Int. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 8, IJH22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.-W.; Ahn, D.-H.; Crawley, S.C.; Li, J.-D.; Gum, J.R.J.; Basbaum, C.B.; Fan, N.Q.; Szymkowski, D.E.; Han, S.-Y.; Lee, B.H.; et al. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate up-regulates the transcription of MUC2 intestinal mucin via Ras, ERK, and NF-kappa B. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 32624–32631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumer, T.; Sinks, L.F. Determining prognosis in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia by phytohemagglutinin (PHA) stimulated lymphocytes. Ann. Saudi Med. 1986, 6, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swart, K.; Hagemeijer, A.; Löwenberg, B. Acute myeloid leukemia colony growth in vitro: Differences of colony-forming cells in PHA-supplemented and standard leukocyte feeder cultures. Blood 1982, 59, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, F.; Oster, W.; Mertelsmann, R. Control of blast cell proliferation and differentiation in acute myelogenous leukemia by soluble polypeptide growth factors. Klin. Padiatr. 1990, 202, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, M.H.; Grunberger, T.; Correa, P.; Axelrad, A.A.; Dube, I.D.; Cohen, A. Autocrine and paracrine growth control by granulocyte-monocyte colony-stimulating factor of acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Blood 1993, 81, 3068–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirro, J.J.; Hurwitz, C.A.; Behm, F.G.; Head, D.R.; Raimondi, S.C.; Crist, W.M.; Ihle, J.N. Effects of recombinant human hematopoietic growth factors on leukemic blasts from children with acute myeloblastic or lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 1993, 7, 1026–1033. [Google Scholar]

- Benko, I.; Kovács, P.; Szegedi, I.; Megyeri, A.; Kiss, A.; Balogh, E.; Oláh, E.; Kappelmayer, J.; Kiss, C. Effect of myelopoietic and pleiotropic cytokines on colony formation by blast cells of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2001, 363, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridgway, D.; Borzy, M.S. Defective production of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-1 by mononuclear cells from children treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 1992, 6, 809–813. [Google Scholar]

- Bhol, N.K.; Bhanjadeo, M.M.; Singh, A.K.; Dash, U.C.; Ojha, R.R.; Majhi, S.; Duttaroy, A.K.; Jena, A.B. The interplay between cytokines, inflammation, and antioxidants: Mechanistic insights and therapeutic potentials of various antioxidants and anti-cytokine compounds. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 178, 117177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paganini, A.; Fritschi, N.; Filippi, C.; Ritz, N.; Simmen, U.; Scheinemann, K.; Filippi, A.; Diesch-Furlanetto, T. Comparative analysis of salivary cytokine profiles in newly diagnosed pediatric patients with cancer and healthy children. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Figueroa, E.; Sánchez-Cuaxospa, M.; Martínez-Soto, K.A.; Sánchez-Zauco, N.; Medina-Sansón, A.; Jiménez-Hernández, E.; Torres-Nava, J.R.; Félix-Castro, J.M.; Gómez, A.; Ortega, E.; et al. Strong inflammatory response and Th1-polarization profile in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia without apparent infection. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 35, 2699–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latoch, E.; Konończuk, K.; Konstantynowicz-Nowicka, K.; Muszyńska-Rosłan, K.; Sztolsztener, K.; Chabowski, A.; Krawczuk-Rybak, M. Asymptomatic Survivors of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Demonstrate a Biological Profile of Inflamm-Aging Early in Life. Cancers 2022, 14, 2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konończuk, K.; Muszyńska-Rosłan, K.; Konstantynowicz-Nowicka, K.; Krawczuk-Rybak, M.; Chabowski, A.; Latoch, E. Biomarkers of Glucose Metabolism Alterations and the Onset of Metabolic Syndrome in Survivors of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhallak, K.; Sun, J.; Muz, B.; Jeske, A.; O’Neal, J.; Ritchey, J.K.; Achilefu, S.; DiPersio, J.F.; Azab, A.K. Liposomal phytohemagglutinin: In vivo T-cell activator as a novel pan-cancer immunotherapy. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2022, 26, 940–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandala, W.; Harawa, V.; Munyenyembe, A.; Soko, M.; Longwe, H. Optimization of stimulation and staining conditions for intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) for determination of cytokine-producing T cells and monocytes. Curr. Res. Immunol. 2021, 2, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, L.; Makyiama, E.N.; Almeida, B.; de Almeida Junior, J.M.; Gonçalves, C.E.d.S.; de Freitas, S.; Amon, R.L.R.; Neves, B.R.O.; Rogero, M.M.; Fock, R.A. Cyanidin-3-glucoside reduces cell migration and inflammatory profile of acute leukemia cells. Nat. Prod. Res. 2025, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.Y.; Lou, X.L.; Wang, Y.; Hou, Y.Q. miR-148b inhibits M2 polarization of LPS-stimulated macrophages by targeting DcR3. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi Chin. J. Prev. Med. 2023, 57, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.S.; Kim, Y.-J.; Han, K.U.; Yoon, B.D.; Kim, J.W. Zymosan and PMA activate the immune responses of Mutz3-derived dendritic cells synergistically. Immunol. Lett. 2015, 167, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-J.; Kang, S.-Y.; Kim, N.-S.; Kim, H.-M. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase regulates PMA-induced differentiation and superoxide production in HL-60 cells. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2002, 24, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaei, M.; Ghanadian, M.; Ghezelbash, B.; Shokouhi, A.; Bazhin, A.V.; Zamyatnin, A.A.J.; Ganjalikhani-Hakemi, M. TIM-3/Gal-9 interaction affects glucose and lipid metabolism in acute myeloid leukemia cell lines. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1267578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandic, M.; Misirkic Marjanovic, M.; Vucicevic, L.; Jovanovic, M.; Bosnjak, M.; Perovic, V.; Ristic, B.; Ciric, D.; Harhaji-Trajkovic, L.; Trajkovic, V. MAP kinase-dependent autophagy controls phorbol myristate acetate-induced macrophage differentiation of HL-60 leukemia cells. Life Sci. 2022, 297, 120481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perbellini, O.; Cavallini, C.; Chignola, R.; Galasso, M.; Scupoli, M.T. Phospho-Specific Flow Cytometry Reveals Signaling Heterogeneity in T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Cell Lines. Cells 2022, 11, 2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Xin, C.; Li, X.; Chang, X.; Jiang, R. NLRP3 participates in the differentiation and apoptosis of PMA-treated leukemia cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2023, 28, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, M.; Thacker, G.; Sharma, A.; Singh, A.K.; Upadhyay, V.; Sanyal, S.; Verma, S.P.; Tripathi, A.K.; Bhatt, M.L.B.; Trivedi, A.K. FBW7 Inhibits Myeloid Differentiation in Acute Myeloid Leukemia via GSK3-Dependent Ubiquitination of PU.1. Mol. Cancer Res. 2021, 19, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharfan-Dabaja, M.; Ayala, E.; Lindner, I.; Cejas, P.J.; Bahlis, N.J.; Kolonias, D.; Carlson, L.M.; Lee, K.P. Differentiation of acute and chronic myeloid leukemic blasts into the dendritic cell lineage: Analysis of various differentiation-inducing signals. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2005, 54, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingett, D.; Long, A.; Kelleher, D.; Magnuson, N.S. pim-1 proto-oncogene expression in anti-CD3-mediated T cell activation is associated with protein kinase C activation and is independent of Raf-1. J. Immunol. 1996, 156, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Growth Factor | Basal/ Stimulated Conditions | AML | T-ALL | BCP-ALL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median Concentration (IQR) [pg/mL] | ||||

| G-CSF | RPMI | 454.87 (596.82) | 52.18 (245.17) | 3.65 (1.74) |

| RPMI + DMSO | 475.93 (582.12) | 27.05 (273.72) | 3.96 (13.05) | |

| PHA | 482.15 (1443.68) | 298.64 (1370.42) | 23.94 (217.08) | |

| PMA + I | 614.55 (1621.03) | 702.12 (1309.62) | 500.24 (1867.88) | |

| LPS | 496.76 (1581.73) | 348.85 (1310.8) | 18.75 (144.54) | |

| GM-CSF | RPMI | 2.7 (3.3) | 0.14 (0.87) | 0.4 (0.81) |

| RPMI + DMSO | 2.42 (2.7) | 0.11 (0.67) | 0.4 (0.67) | |

| PHA | 6.52 (12.65) | 1.31 (1.71) | 0.89 (3.05) | |

| PMA + I | 25.46 (23.4) | 12.36 (190.95) | 5.66 (16.97) | |

| LPS | 3.96 (8.79) | 1.85 (3.36) | 0.75 (1.49) | |

| basic FGF | RPMI | 39.98 (46.97) | 14.89 (22.0) | 9.07 (12.13) |

| RPMI + DMSO | 38.07 (46.89) | 10.82 (30.5) | 9.96 (11.46) | |

| PHA | 77.12 (122.78) | 49.20 (119.66) | 15.61 (28.08) | |

| PMA + I | 124.09 (191.19) | 75.01 (110.85) | 89.16 (131.03) | |

| LPS | 59.78 (105.8) | 61.67 (98.99) | 10.99 (19.55) | |

| VEGF | RPMI | 240.12 (122.87) | 136.05 (149.43) | 147.21 (97.4) |

| RPMI + DMSO | 221.05 (177.88) | 74.53 (92.52) | 130.57 (108.49) | |

| PHA | 375.36 (293.75) | 264.12 (266.69) | 158.47 (161.4) | |

| PMA + I | 432.3 (225.51) | 307.07 (259.52) | 397.5 (490.74) | |

| LPS | 381.85 (278.29) | 241.85 (190.55) | 149.09 (110.59) | |

| PDGF | RPMI | 20.15 (23.05) | 20.85 (22.25) | 14.22 (15.96) |

| RPMI + DMSO | 26.27 (13.67) | 20.20 (29.31) | 11.84 (16.2) | |

| PHA | 58.6 (59.27) | 56.50 (55.00) | 17.01 (7.68) | |

| PMA + I | 119.38 (173.99) | 63.87 (104.5) | 68.72 (163.36) | |

| LPS | 48.56 (62.90) | 62.28 (62.85) | 9.66 (19.23) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kozub, A.; Szarek, R.; Szczęsny, M.; Jaworska, D.; Młynarski, W.; Kowalczyk, J.; Szczepański, T.; Czuba, Z.P.; Sędek, Ł. Profiles of Growth Factors Secreted by In Vitro-Stimulated Paediatric Acute Leukaemia Blasts of Myeloid and Lymphoid Origin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 933. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020933

Kozub A, Szarek R, Szczęsny M, Jaworska D, Młynarski W, Kowalczyk J, Szczepański T, Czuba ZP, Sędek Ł. Profiles of Growth Factors Secreted by In Vitro-Stimulated Paediatric Acute Leukaemia Blasts of Myeloid and Lymphoid Origin. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):933. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020933

Chicago/Turabian StyleKozub, Anna, Rafał Szarek, Mikołaj Szczęsny, Dagmara Jaworska, Wojciech Młynarski, Jerzy Kowalczyk, Tomasz Szczepański, Zenon P. Czuba, and Łukasz Sędek. 2026. "Profiles of Growth Factors Secreted by In Vitro-Stimulated Paediatric Acute Leukaemia Blasts of Myeloid and Lymphoid Origin" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 933. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020933

APA StyleKozub, A., Szarek, R., Szczęsny, M., Jaworska, D., Młynarski, W., Kowalczyk, J., Szczepański, T., Czuba, Z. P., & Sędek, Ł. (2026). Profiles of Growth Factors Secreted by In Vitro-Stimulated Paediatric Acute Leukaemia Blasts of Myeloid and Lymphoid Origin. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 933. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020933