Recombinant Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor Derived from Trichinella spiralis Suppresses Obesity by Reducing Body Fat and Inflammation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Structural Differences Between T. spiralis MIF and M. musculus MIF

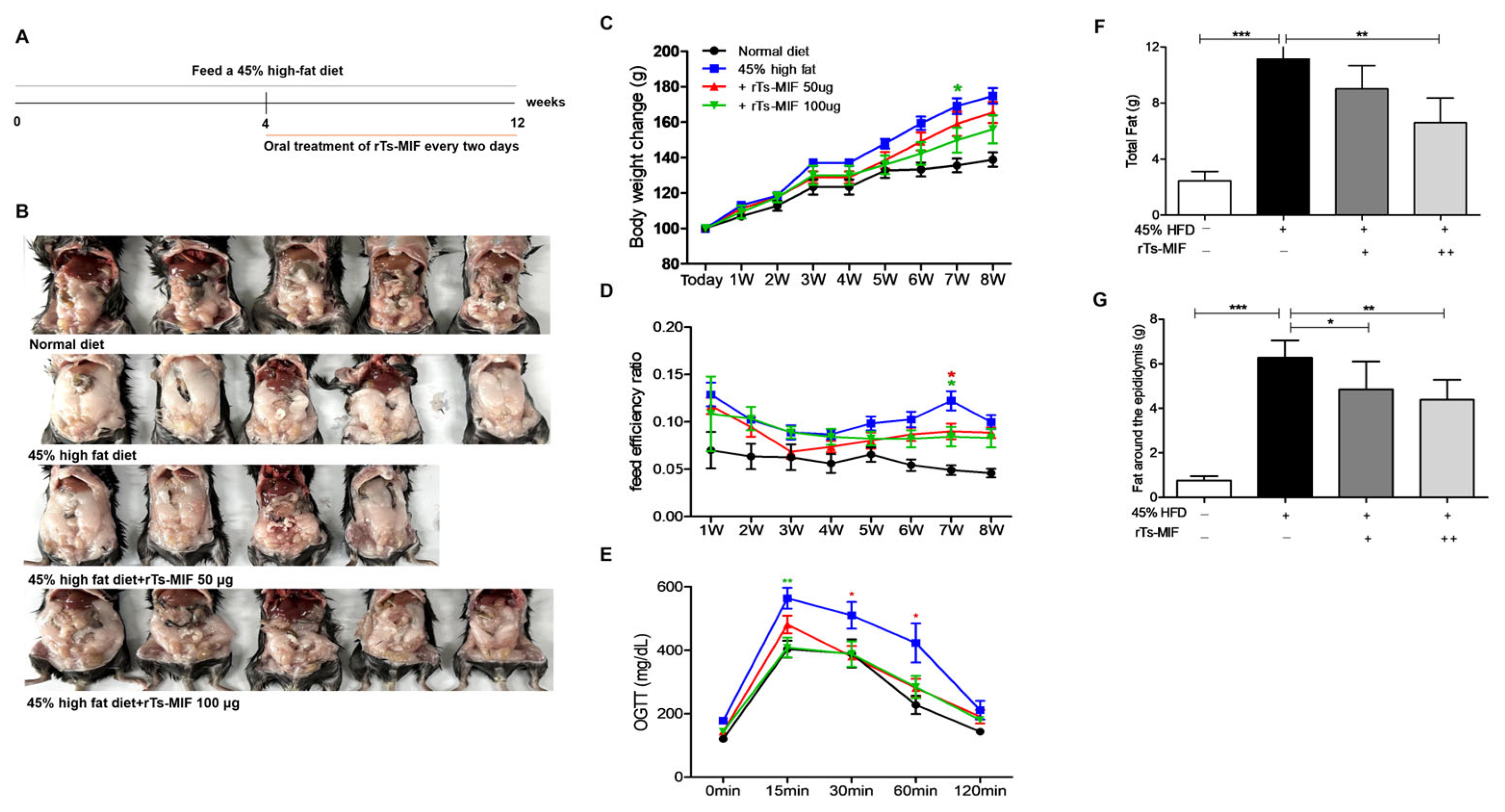

2.2. rTs-MIF Reduces Obesity in Mice

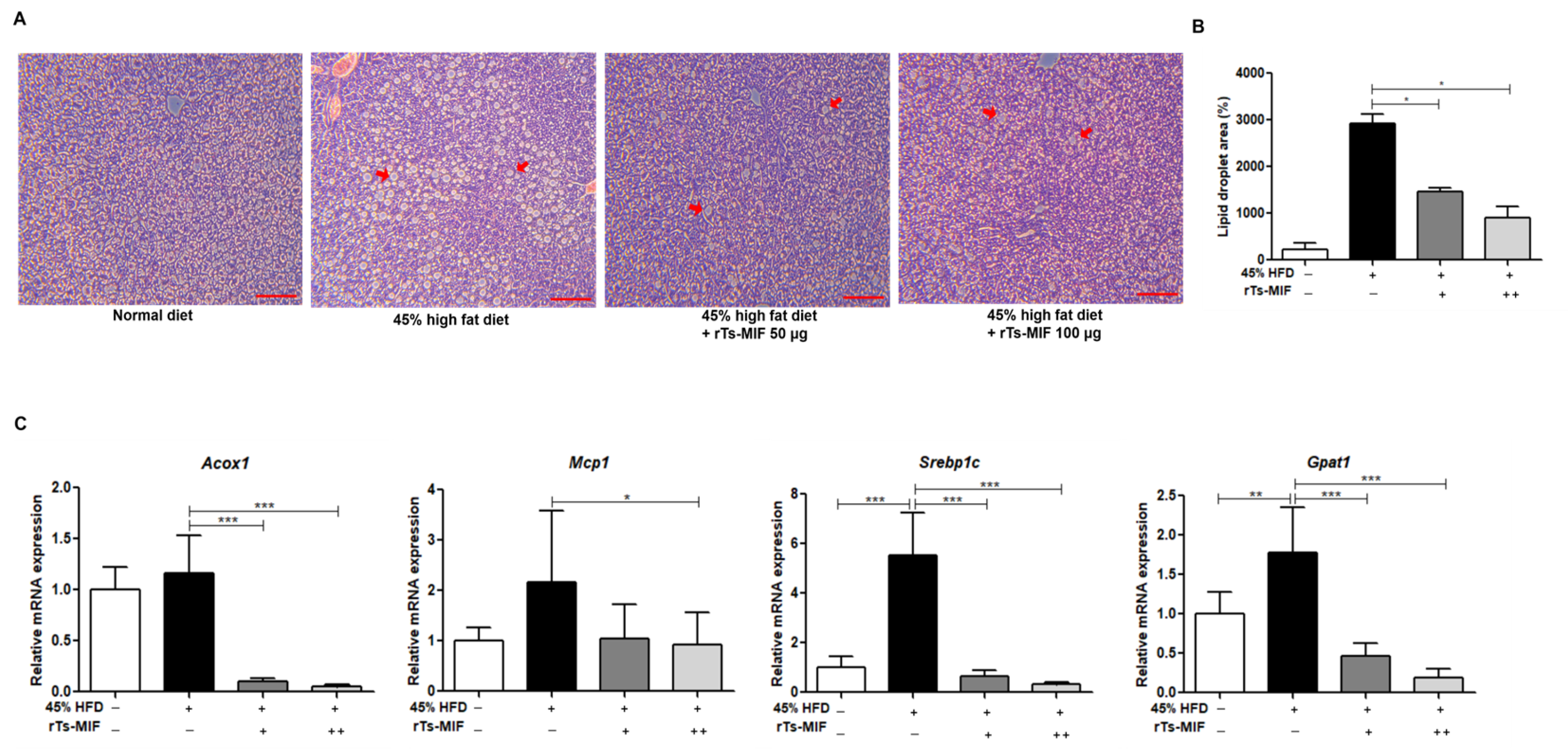

2.3. rTs-MIF Inhibits Hepatic Lipid Accumulation and Lipogenic Gene Expression

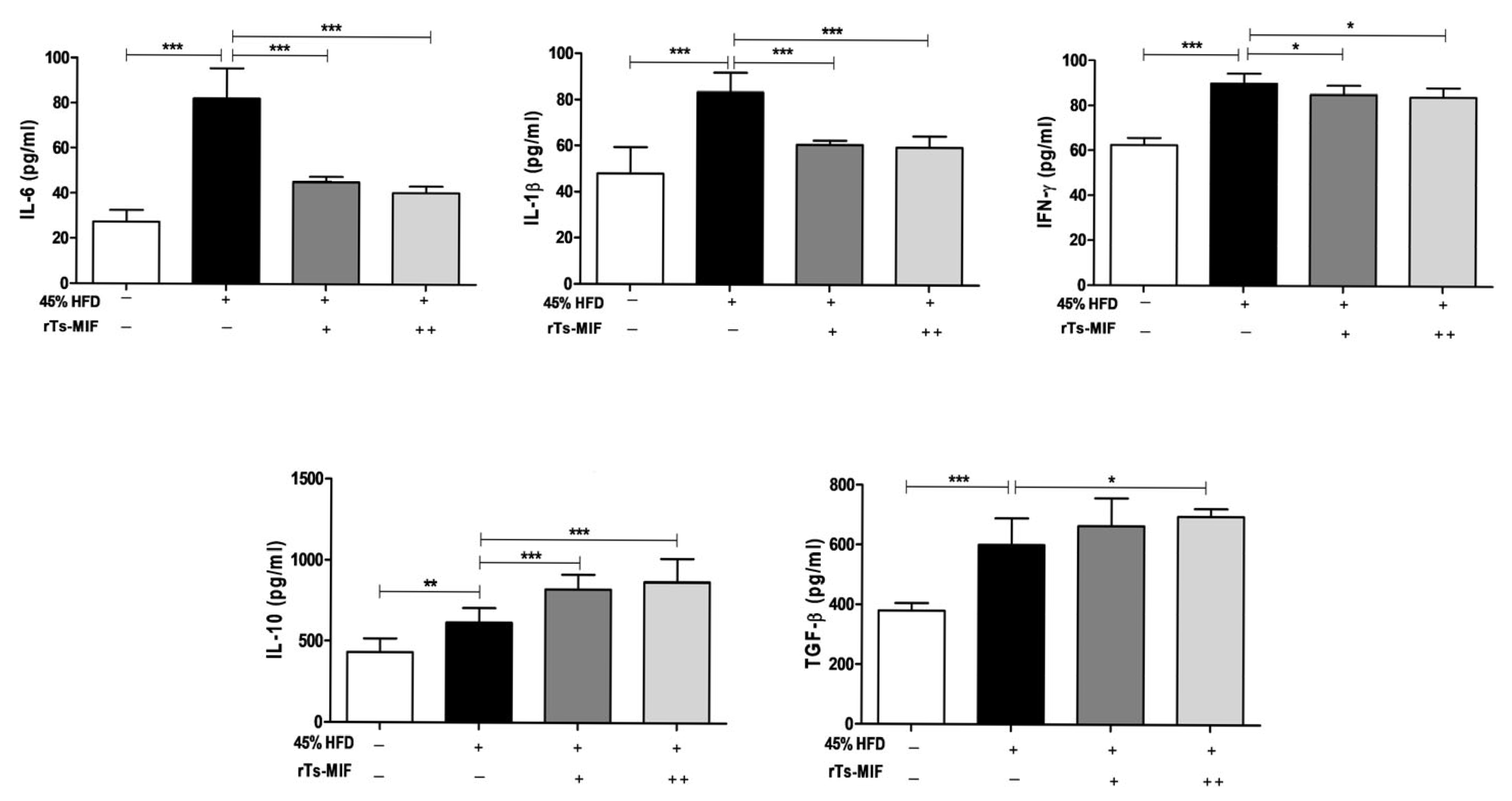

2.4. rTs-MIF Decreases Th1 Cytokines and Increases Th2 Cytokines

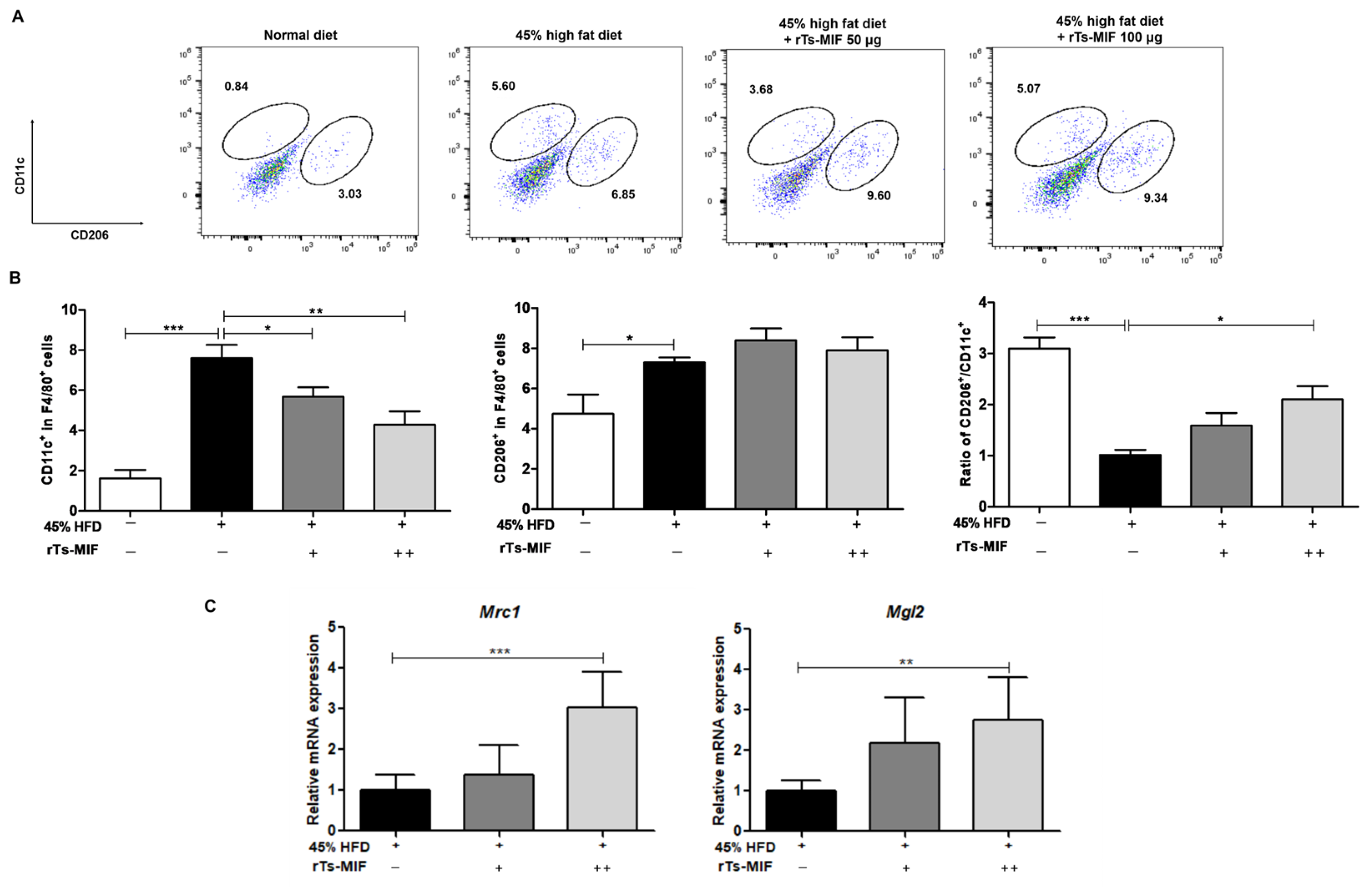

2.5. rTs-MIF Modulates Macrophage Composition in White Adipose Tissue

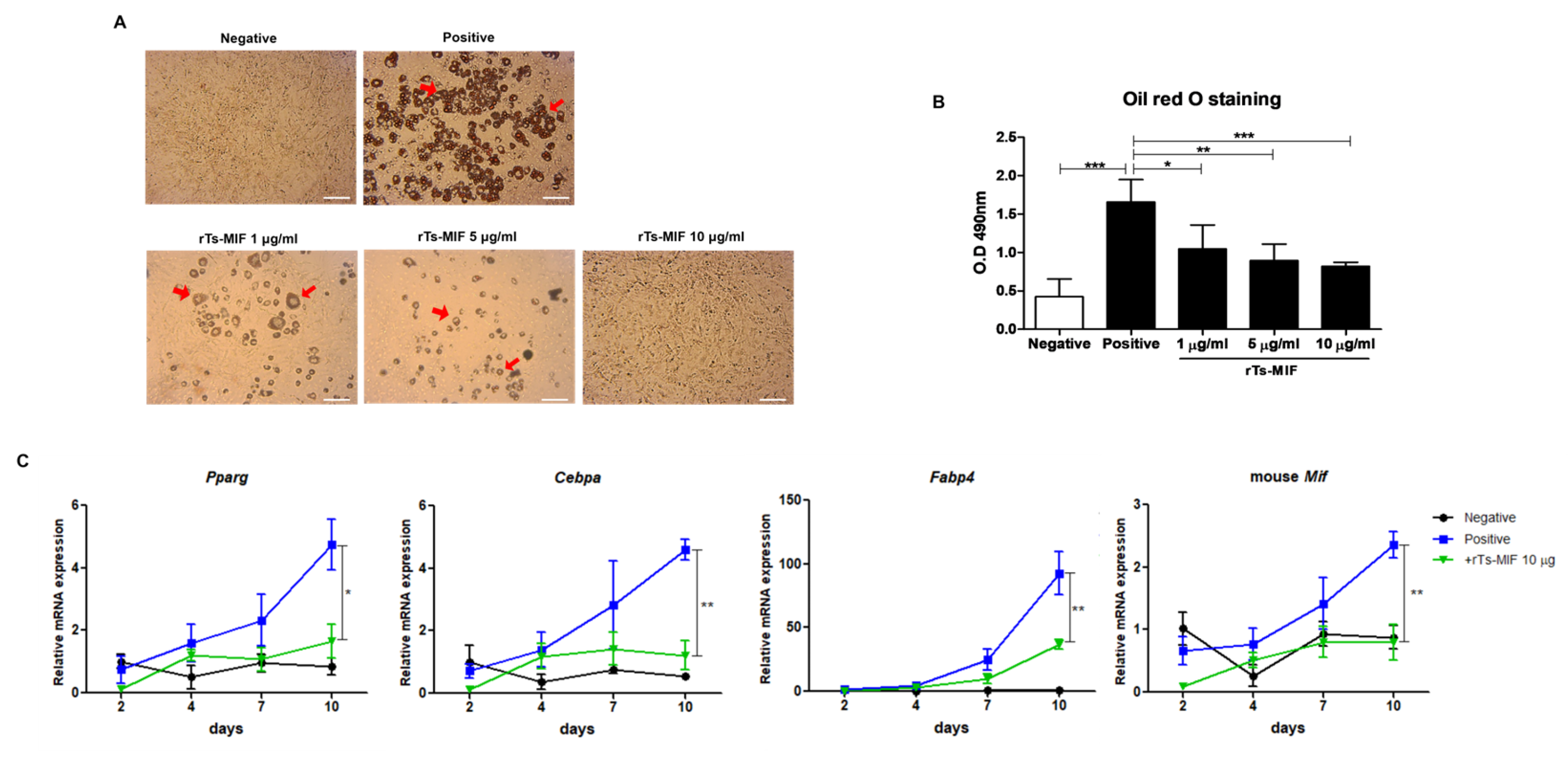

2.6. rTs-MIF Inhibits Adipocyte Differentiation in 3T3-L1 Cells

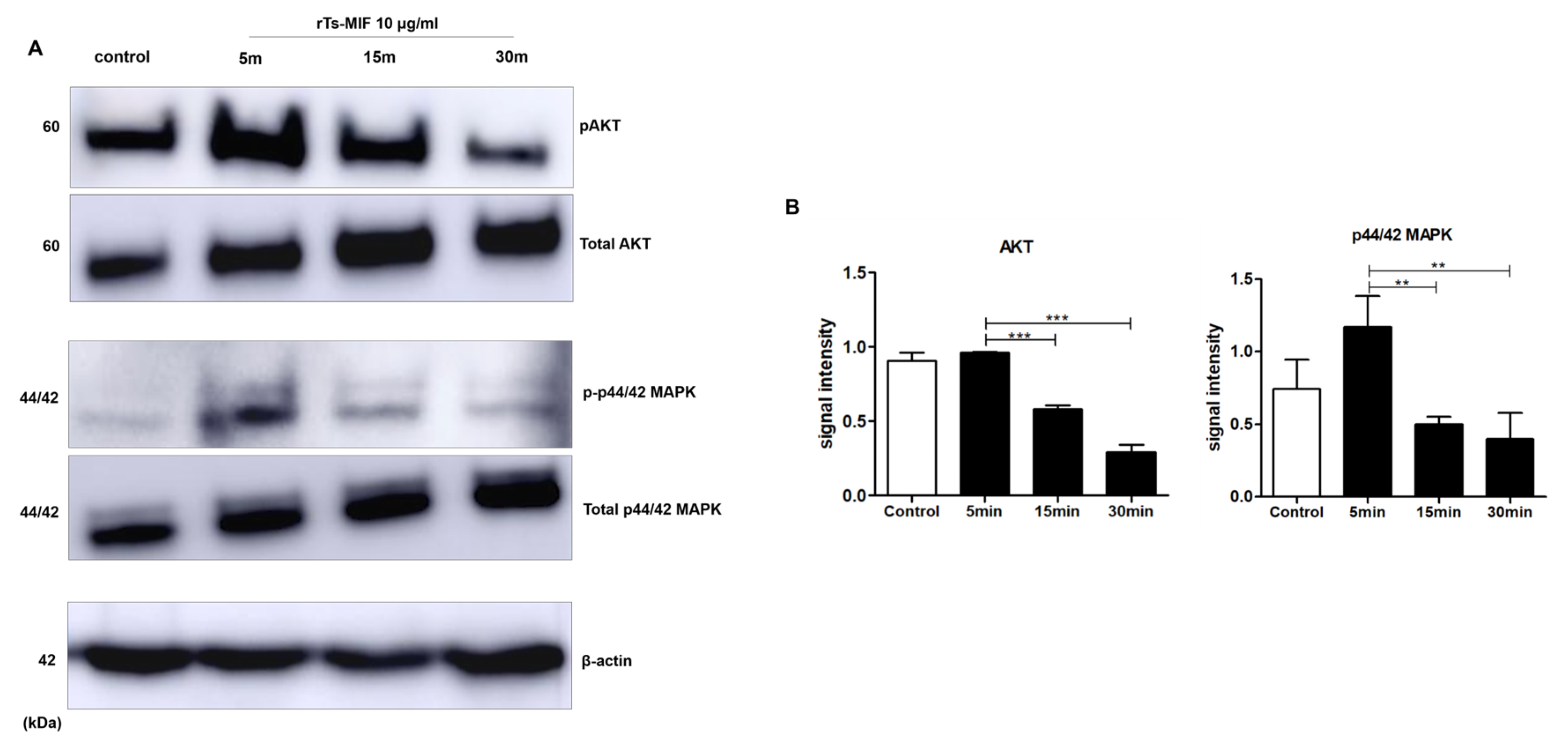

2.7. rTs-MIF Modulates Obesity-Related Signaling Pathways During Early 3T3-L1 Differentiation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Protein Expression and Purification

4.2. Mice and Diet

4.3. Measurement of Body Fat Mass and Adipose Tissue Weight

4.4. Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT)

4.5. Histological Analysis

4.6. RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

4.7. Cytokine Analysis Using ELISA

4.8. Flow Cytometry (FACS)

4.9. 3T3-L1 Cell Culture and Differentiation

4.10. Oil Red O Staining

4.11. Western Blot Analysis

4.12. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Felipe Parra Velasco, P. Obesity and Cardiovascular Risk. In Novel Pathogenesis and Treatments for Cardiovascular Disease; Gaze, D.C., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- La Sala, L.; Pontiroli, A.E. Prevention of Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease in Obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antouri, Z.; Mezouaghi, A.; Djilali, S.; Zeb, A.; Khan, I.; Omer, A.S.A. The impact of obesity on chronic diseases: Type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and high blood pressure. Appl. Math. Sci. Eng. 2024, 32, 2422061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyaolu, A.; Okorie, C.; Qi, X.; Locke, J.; Rehman, S. Childhood and Adolescent Obesity in the United States: A Public Health Concern. Glob. Pediatr. Health 2019, 6, 2333794X19891305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, E.A.; Khavjou, O.A.; Thompson, H.; Trogdon, J.G.; Pan, L.; Sherry, B.; Dietz, W. Obesity and Severe Obesity Forecasts Through 2030. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 42, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaacks, L.M.; Vandevijvere, S.; Pan, A.; McGowan, C.J.; Wallace, C.; Imamura, F.; Mozaffarian, D.; Swinburn, B.; Ezzati, M. The obesity transition: Stages of the global epidemic. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019, 7, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, D. Pharmacotherapy for the management of obesity. Metabolism 2015, 64, 1376–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, G.A.; Frühbeck, G.; Ryan, D.H.; Wilding, J.P. Management of obesity. Lancet 2016, 387, 1947–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupnicka, P.; Król, M.; Żychowska, J.; Łagowski, R.; Prajwos, E.; Surówka, A.; Chlubek, D. GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: A Promising Therapy for Modern Lifestyle Diseases with Unforeseen Challenges. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.G.; Park, C.-Y. Anti-obesity drugs: A review about their effects and safety. Diabetes Metab. J. 2012, 36, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinkajzlová, A.; Mráz, M.; Haluzík, M. Adipose tissue immune cells in obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular diseases. J. Endocrinol. 2022, 252, R1–R22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chylikova, J.; Dvorackova, J.; Tauber, Z.; Kamarad, V. M1/M2 macrophage polarization in human obese adipose tissue. Biomed. Pap. 2018, 162, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, T.; Autieri, M.V.; Scalia, R. Adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in obesity. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2021, 320, C375–C391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern, L.; Mittenbühler, M.J.; Vesting, A.J.; Ostermann, A.L.; Wunderlich, C.M.; Wunderlich, F.T. Obesity-induced TNFα and IL-6 signaling: The missing link between obesity and inflammation—Driven liver and colorectal cancers. Cancers 2019, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, M.; Yang, X.; Yu, Y.; Pan, W. Helminth and host crosstalk: New insight into treatment of obesity and its associated metabolic syndromes. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 827486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.w.; Chen, C.-Y.; Li, Y.; Long, S.R.; Massey, W.; Kumar, D.V.; Walker, W.A.; Shi, H.N. Helminth infection protects against high fat diet-induced obesity via induction of alternatively activated macrophages. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.A.; Choi, J.H.; Baek, K.-W.; Lee, D.I.; Jeong, M.-J.; Yu, H.S. Trichinella spiralis infection ameliorated diet-induced obesity model in mice. Int. J. Parasitol. 2021, 51, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.A.; Yu, H.S. Anti-obesity effects by parasitic nematode (Trichinella spiralis) total lysates. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 13, 1285584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumaiya, K.; Langford, D.; Natarajaseenivasan, K.; Shanmughapriya, S. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF): A multifaceted cytokine regulated by genetic and physiological strategies. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 233, 108024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Leng, L.; Wang, T.; Wang, W.; Du, X.; Li, J.; McDonald, C.; Chen, Z.; Murphy, J.W.; Lolis, E.; et al. CD44 is the signaling component of the macrophage migration inhibitory factor-CD74 receptor complex. Immunity 2006, 25, 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.-Z.; Chen, Q.; Lan, H.-Y. Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor (MIF) as a Stress Molecule in Renal Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, M.K.; Lee, C.H.; Yu, H.S. Amelioration of intestinal colitis by macrophage migration inhibitory factor isolated from intestinal parasites through Toll-like receptor 2. Parasite Immunol. 2011, 33, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.K.; Park, M.K.; Kang, S.A.; Park, S.K.; Lyu, J.H.; Kim, D.H.; Park, H.K.; Yu, H.S. TLR2-dependent amelioration of allergic airway inflammation by parasitic nematode type II MIF in mice. Parasite Immunol. 2015, 37, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.K.; Cho, M.K.; Park, H.K.; Lee, K.H.; Lee, S.J.; Choi, S.H.; Ock, M.S.; Jeong, H.J.; Lee, M.H.; Yu, H.S. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor homologs of Anisakis simplex suppress Th2 response in allergic airway inflammation model via CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cell recruitment. J. Immunol. 2009, 182, 6907–6914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.-W.; Swope, M.; Craig, C.; Bedarkar, S.; Bernhagen, J.; Bucala, R.; Lolis, E. The subunit structure of human macrophage migration inhibitory factor: Evidence for a trimer. Protein Eng. 1996, 9, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, H.; Tang, D.W.T.; Wong, S.H.; Lal, D. Helminths in alternative therapeutics of inflammatory bowel disease. Intest. Res. 2025, 23, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maizels, R.M.; McSorley, H.J. Regulation of the host immune system by helminth parasites. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 138, 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Zande, H.J.P.; Zawistowska-Deniziak, A.; Guigas, B. Immune Regulation of Metabolic Homeostasis by Helminths and Their Molecules. Trends Parasitol. 2019, 35, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikder, S.; Pierce, D.; Sarkar, E.R.; McHugh, C.; Quinlan, K.G.R.; Giacomin, P.; Loukas, A. Regulation of host metabolic health by parasitic helminths. Trends Parasitol. 2024, 40, 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Luca, C.; Olefsky, J.M. Inflammation and insulin resistance. FEBS Lett. 2008, 582, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Chen, R.; Wang, H.; Liang, F. Mechanisms Linking Inflammation to Insulin Resistance. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 2015, 508409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziolkowska, S.; Binienda, A.; Jabłkowski, M.; Szemraj, J.; Czarny, P. The Interplay between Insulin Resistance, Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, Base Excision Repair and Metabolic Syndrome in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, A.; Chen, X.; Tan, M.; Chen, Y.; Lu, D.; Zhang, X.; Dean, J.M.; Razani, B.; Lodhi, I.J. Acetyl-CoA Derived from Hepatic Peroxisomal β-Oxidation Inhibits Autophagy and Promotes Steatosis via mTORC1 Activation. Mol. Cell 2020, 79, 30–42.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, L.; Huang, L.; Xue, Q.; Liu, C.; Xu, K.; Shen, W.; Deng, L. Cell-specific elevation of Runx2 promotes hepatic infiltration of macrophages by upregulating MCP-1 in high-fat diet-induced mice NAFLD. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 11761–11774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.T.P.; Kim, D.-Y.; Lee, Y.-G.; Lee, Y.-S.; Truong, X.T.; Lee, J.-H.; Song, D.-K.; Kwon, T.K.; Park, S.-H.; Jung, C.H.; et al. SREBP-1c impairs ULK1 sulfhydration-mediated autophagic flux to promote hepatic steatosis in high-fat-diet-fed mice. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 3820–3832.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, K.R.; Wang, W.; Miller, M.R.; Boucher, M.; Reynold, J.E.; Daurio, N.A.; Li, D.; Hirenallur-Shanthappa, D.; Ahn, Y.; Beebe, D.A.; et al. GPAT1 Deficiency in Mice Modulates NASH Progression in a Model-Dependent Manner. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 17, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.M.; Macedo-de la Concha, L.E.; Pantoja-Meléndez, C.A. Low-grade inflammation and its relation to obesity and chronic degenerative diseases. Rev. Méd. Hosp. Gen. Méx. 2017, 80, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.C.; He, S.H. IL-10 and its related cytokines for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2004, 10, 620–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Chung, B.Y.; Lee, M.-K.; Song, Y.; Lee, S.S.; Chu, G.M.; Kang, S.-N.; Song, Y.M.; Kim, G.-S.; Cho, J.-H. Centipede grass exerts anti-adipogenic activity through inhibition of C/EBPβ, C/EBPα, and PPARγ expression and the AKT signaling pathway in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 12, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finucane, O.M.; Reynolds, C.M.; McGillicuddy, F.C.; Harford, K.A.; Morrison, M.; Baugh, J.; Roche, H.M. Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor Deficiency Ameliorates High-Fat Diet Induced Insulin Resistance in Mice with Reduced Adipose Inflammation and Hepatic Steatosis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudry, A.; Yang, Z.-Z.; Hemmings, B.A. PKBα is required for adipose differentiation of mouse embryonic fibroblasts. J. Cell Sci. 2006, 119, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, G.; Mei, C.; Li, S.; Zhang, W.; Junjvlieke, Z.; Zan, L. MiR-145 reduces the activity of PI3K/Akt and MAPK signaling pathways and inhibits adipogenesis in bovine preadipocytes. Genomics 2020, 112, 2688–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeire, J.J.; Cho, Y.; Lolis, E.; Bucala, R.; Cappello, M. Orthologs of macrophage migration inhibitory factor from parasitic nematodes. Trends Parasitol. 2008, 24, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabowicz, J.; Długosz, E.; Bąska, P.; Wiśniewski, M. Nematode Orthologs of Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor (MIF) as Modulators of the Host Immune Response and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Pathogens 2022, 11, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Gapdh-for 1 | 5′-CAT CAC TGC CAC CCA GAA GAC TG-3′ |

| Gapdh-rev | 5′-ATG CCA GTG AGC TTC CCG TTC AG-3′ |

| Acox1-for | 5′-GCC ATT CGA TAC AGT GCT GTG AG-3′ |

| Acox1-rev | 5′-CCG AGA AAG TGG AAG GCA TAG G-3′ |

| Mcp1-for | 5′-GCT ACA AGA GGA TCA CCA GCA G-3′ |

| Mcp1-rev | 5′-GTC TGG ACC CAT TCC TTC TTG G-3′ |

| Srebp1c-for | 5′-GGA GCC ATG GAT TGC ACA TT-3′ |

| Srebp1c-rev | 5′-GGC CCG GGA AGT CAC TGT-3′ |

| Gpat1-for | 5′-GCA AGC ACT GTT ACC AGC GAT C-3′ |

| Gpat1-rev | 5′-TGC AAT CAG CCT TCG TCG GAA G-3′ |

| Mgl2-for | 5′-CGA GAC TTG AGC CAG AAG GTG A-3′ |

| Mgl2-rev | 5′-GCC TTC AAG TCT GTC TCC AGC T-3′ |

| Mrc1-for | 5′-CAG GTG TGG GCT CAG GTA GT-3′ |

| Mrc1-rev | 5′-TGT GGT GAG CTG AAA GGT GA-3′ |

| Pparg-for | 5′-GCC TCC TGG TGA CTT TAT GGA-3′ |

| Pparg-rev | 5′-GCA GCA GGT TGT CTT GGA TG-3′ |

| Cebpa-for | 5′-CAA AGC CAA GAA GTC GGT GGA CAA-3′ |

| Cebpa-rev | 5′-TCA TTG TGA CTG GTC AAC TCC AGC-3′ |

| Fabp4-for | 5′-TGA AAT CAC CGC AGA CGA CAG G-3′ |

| Fabp4-rev | 5′-GCT TGT CAC CAT CTC GTT TTC TC-3′ |

| mouse Mif-for | 5′-ATG CCT ATG TTC ATC GTG-3′ |

| mouse Mif-rev | 5′-TCA AGC GAA GGT GGA ACC-3′ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Choi, S.Y.; Park, M.-K.; Jeong, Y.J.; Han, D.G.; Jin, C.; Han, C.W.; Jang, S.B.; Kang, S.A.; Yu, H.S. Recombinant Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor Derived from Trichinella spiralis Suppresses Obesity by Reducing Body Fat and Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 887. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020887

Choi SY, Park M-K, Jeong YJ, Han DG, Jin C, Han CW, Jang SB, Kang SA, Yu HS. Recombinant Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor Derived from Trichinella spiralis Suppresses Obesity by Reducing Body Fat and Inflammation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):887. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020887

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Seo Yeong, Mi-Kyung Park, Yu Jin Jeong, Dong Gyu Han, Chaeeun Jin, Chang Woo Han, Se Bok Jang, Shin Ae Kang, and Hak Sun Yu. 2026. "Recombinant Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor Derived from Trichinella spiralis Suppresses Obesity by Reducing Body Fat and Inflammation" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 887. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020887

APA StyleChoi, S. Y., Park, M.-K., Jeong, Y. J., Han, D. G., Jin, C., Han, C. W., Jang, S. B., Kang, S. A., & Yu, H. S. (2026). Recombinant Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor Derived from Trichinella spiralis Suppresses Obesity by Reducing Body Fat and Inflammation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 887. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020887