ΔFW-NPS6-Dependent Transcriptome Profiling Reveals Putative Pathogenicity Genes in Fusarium oxysporum

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Distribution of Mapped Reads

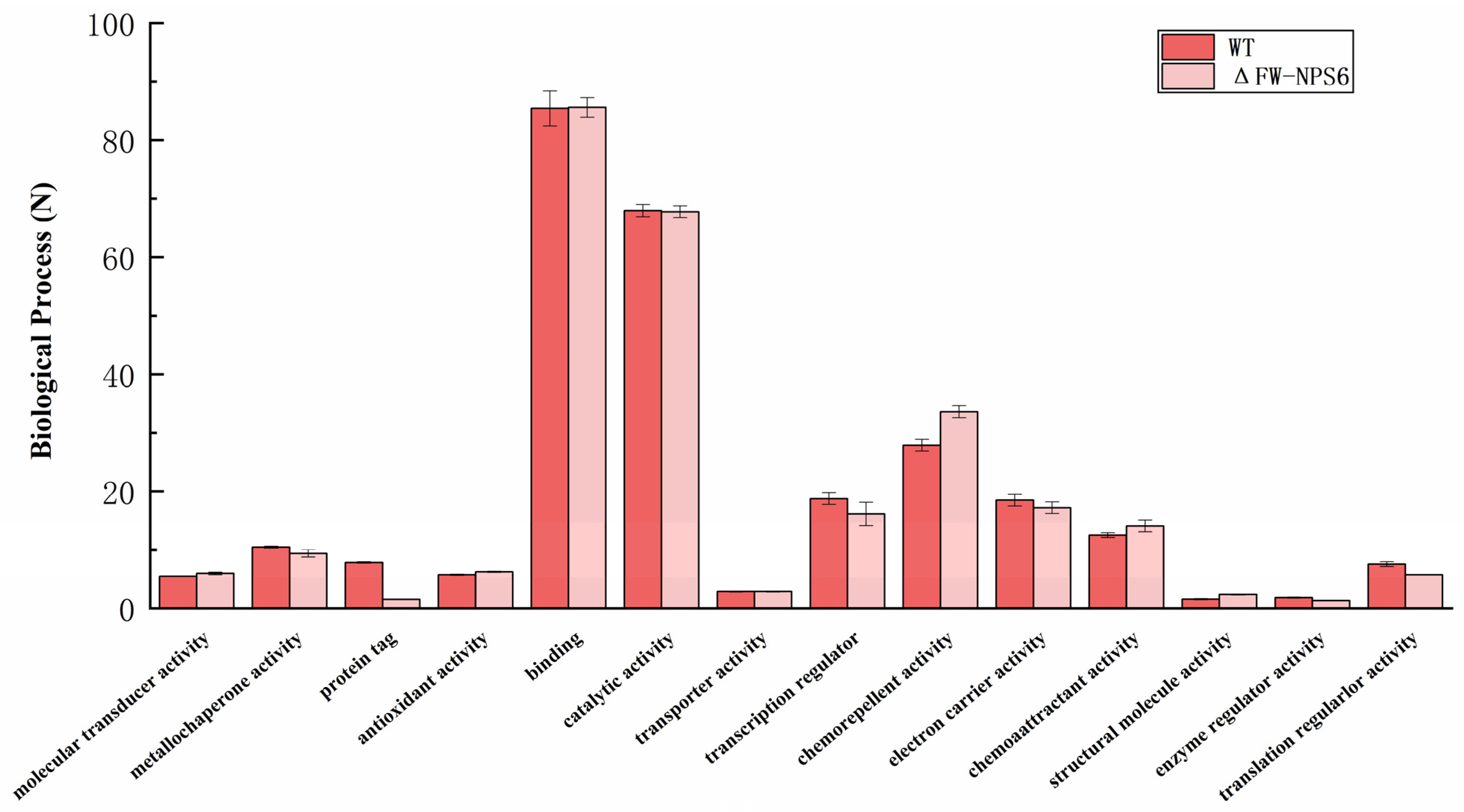

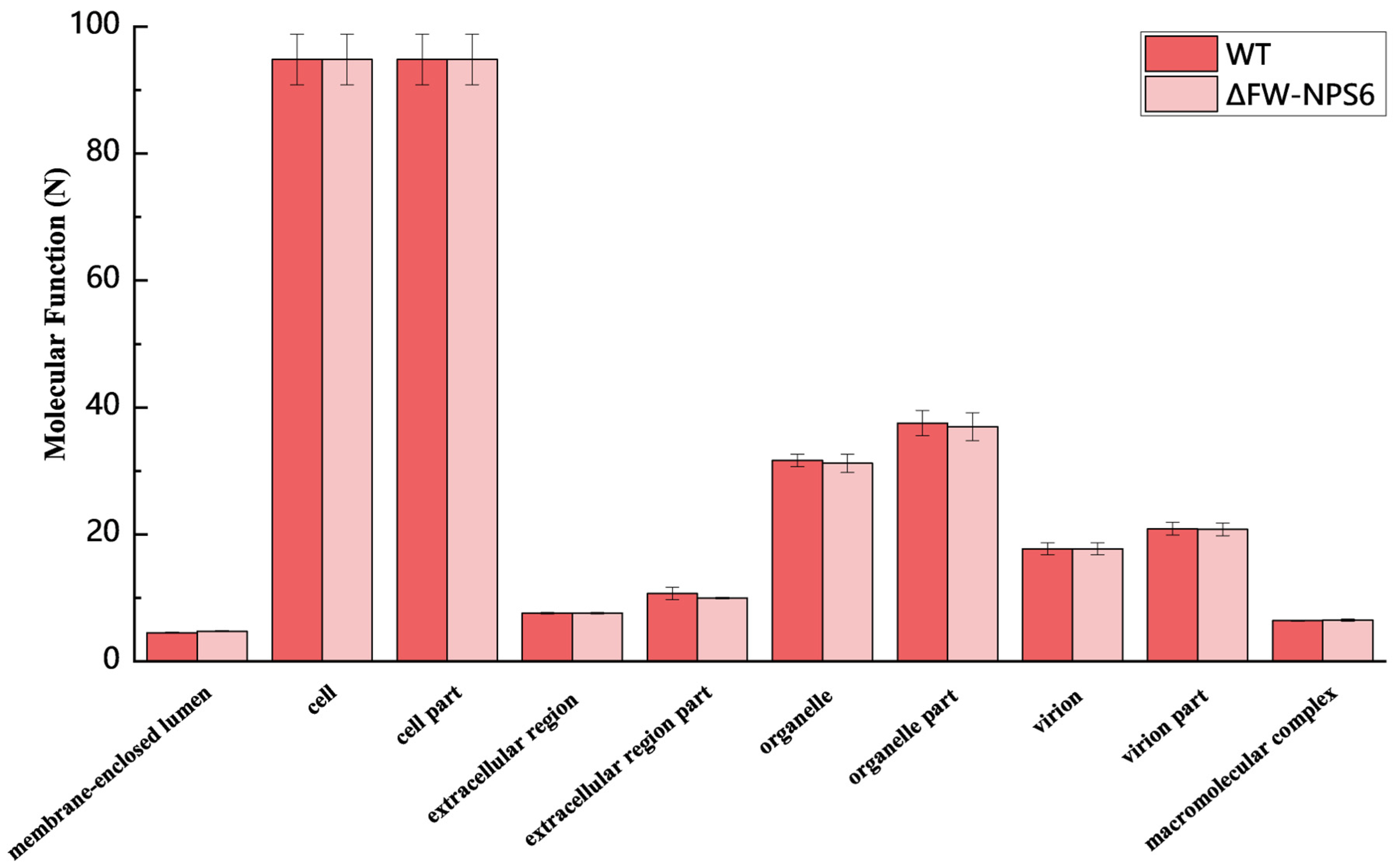

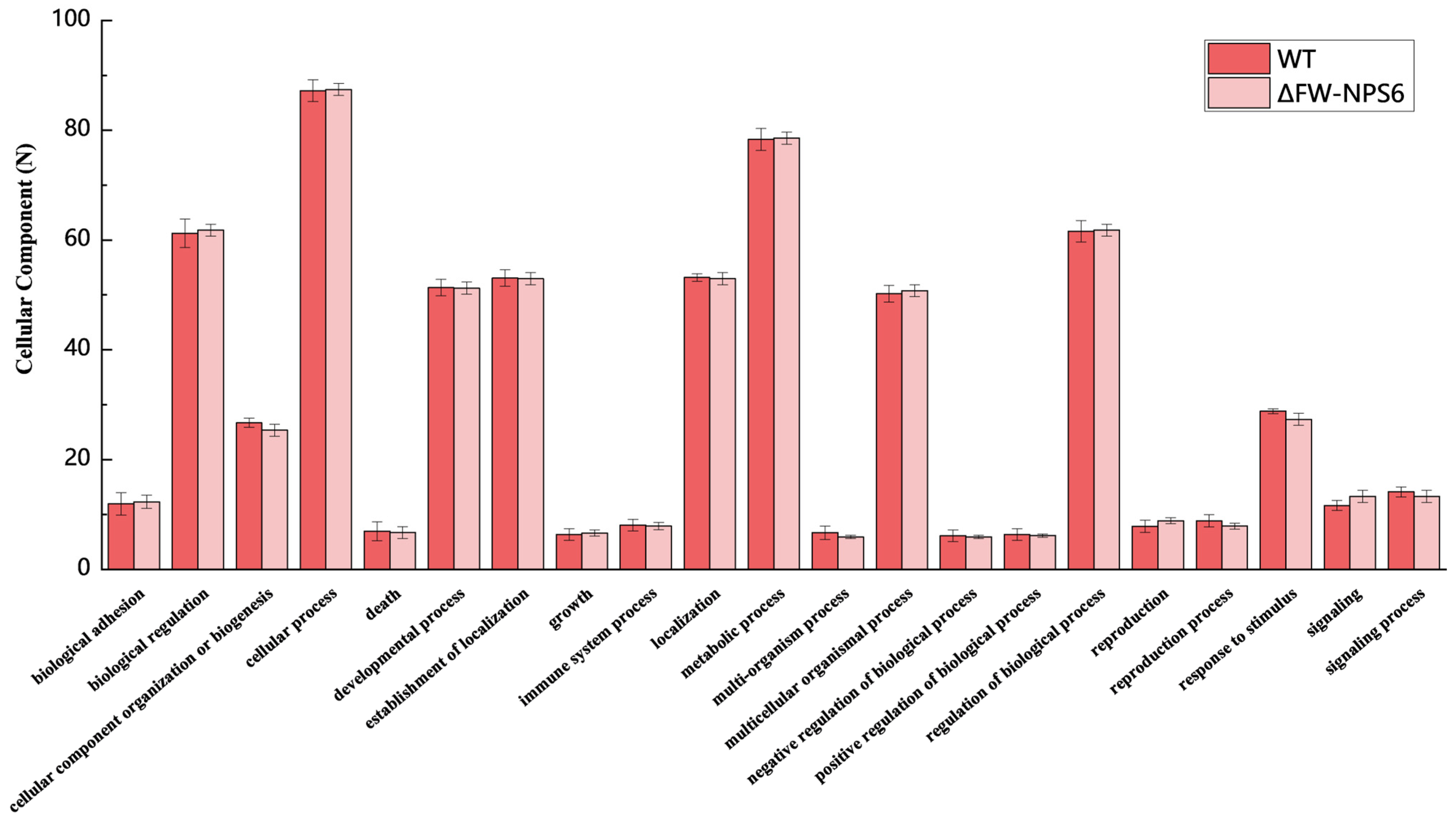

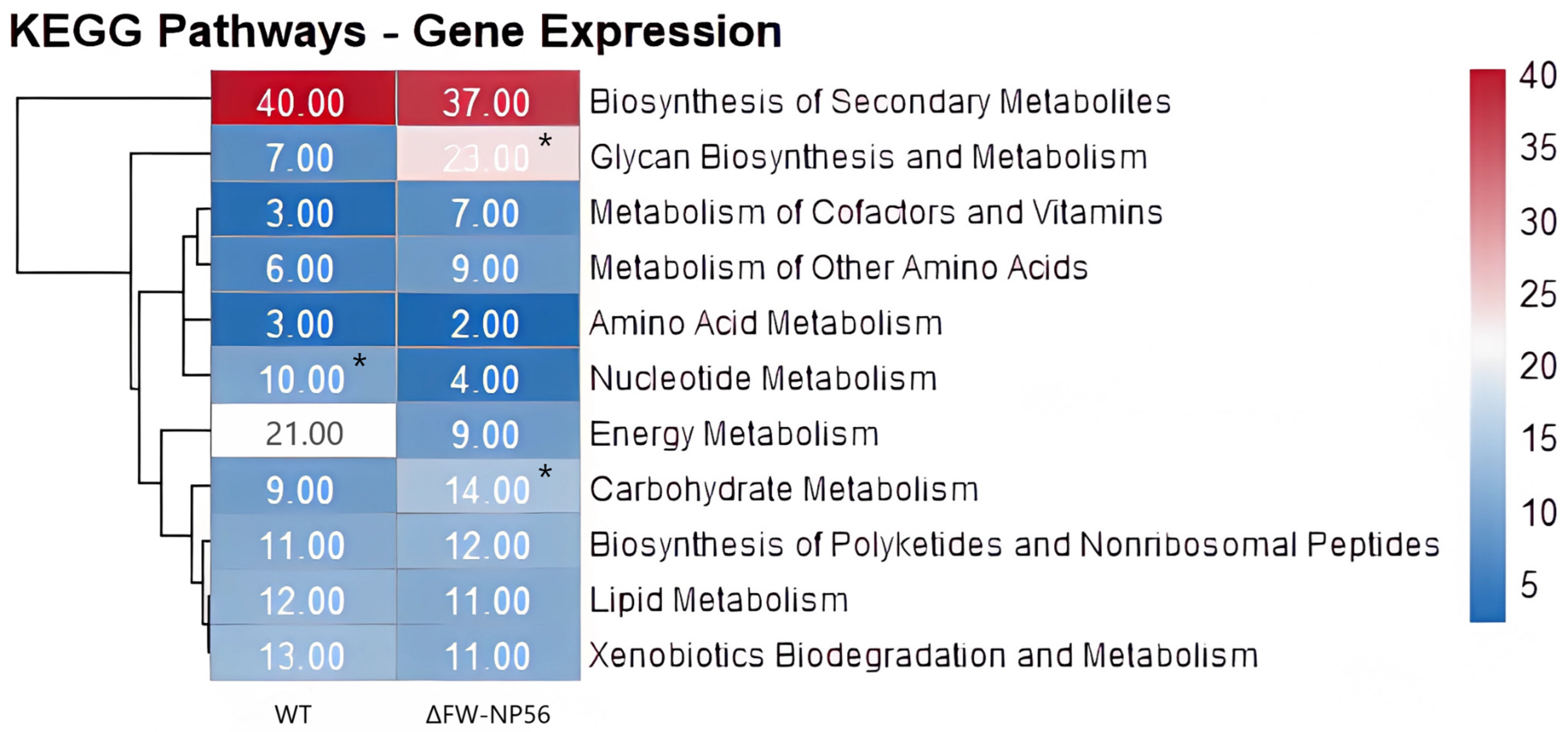

2.2. Gene Ontology (GO) Classification

2.3. Identification of the Differentially Expressed Genes

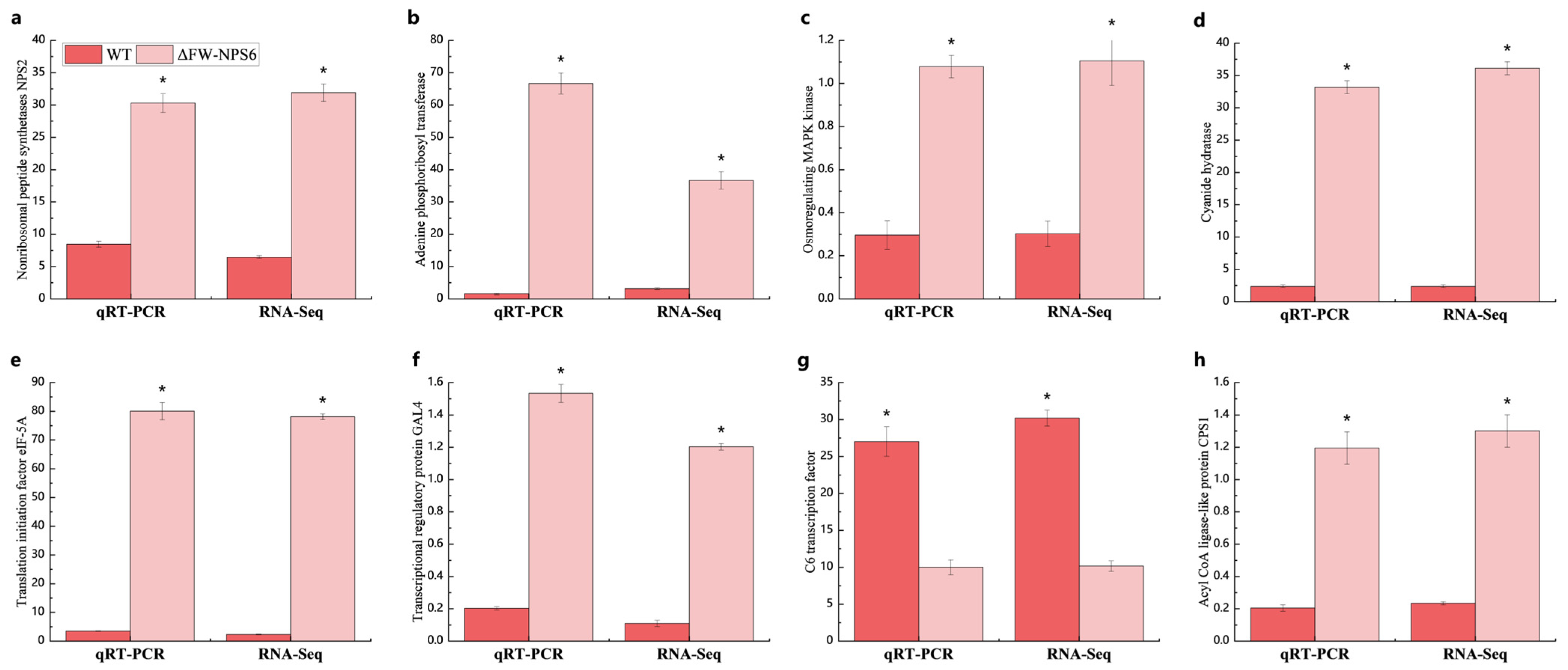

2.4. Identification of High-Confidence NPS6-Dependent Genes

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sampling of Mutant Strains

4.2. RNA Isolation, cDNA Library Preparation and Sequencing

4.3. Read Mapping and Gene Annotation

4.4. Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes

4.5. Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase (qRT-PCR)

4.6. Data Access

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, J.; Gao, Y.; Li, B.; Zhang, L.; Fang, Y.; Zou, H.; Ye, X. FONPS6, a Nonribosomal Peptide Synthetase, Plays a Crucial Role in Achieving the Full Virulence Potential of the Vascular Wilt Pathogen Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. niveum. Life 2025, 15, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, M.; Stork, M.; Naka, H.; Tolmasky, M.E.; Crosa, J.H. Tandem heterocyclization domains in a nonribosomal peptide synthetase essential for siderophore biosynthesis in Vibrio anguillarum. BioMetals 2008, 21, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Shi, J. FgIlv5 is required for branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis and full virulence in Fusarium graminearum. Microbiology 2014, 160, 692–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Xue, C.; Peng, Y.; Katan, T.; Kistler, H.C.; Xu, J.R. A mitogen-activated protein kinase gene (MGV1) in Fusarium graminearum is required for female fertility, heterokaryon formation, and plant infection. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2002, 15, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Wang, Y.M.; Ye, X.H.; Lin, X.G.; Dai, X.; Wang, J.W.; Xie, X.Q. Effects of soil habitat factors on growth of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. niveum and Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Cucumerinum. Soil 2014, 46, 845–850. [Google Scholar]

- Michielse, C.B.; Van, W.R.; Reijnen, L.; Cornelissen, B.J.; Rep, M. Insight into the molecular requirements for pathogenicity of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici through large-scale insertional mutagenesis. Genome Biol. 2009, 10, R4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Dolfing, J.; Guo, Z.; Liu, J.; Pan, X.; Cui, X.; Wang, Y.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, R.; et al. Warmer summers have the potential to affect food security by increasing the prevalence and activity of Actinobacteria. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2025, 124, 103708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, P.A.; Garcia-MacEira, F.I.; Meglecz, E.; Roncero, M.I. A MAP kinase of the vascular wilt fungus Fusarium oxysporum is essential for root penetration and pathogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 1140–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rispail, N.; Di, P.A. Fusarium oxysporum Ste12 controls invasive growth and virulence downstream of the Fmk1 MAPK cascade. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2009, 22, 830–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Diener, A.C. Arabidopsis thaliana resistance to Fusarium oxysporum 2 implicates tyrosine-sulfated peptide signaling in susceptibility and resistance to root infection. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oide, S.; Moeder, W.; Krasnoff, S.; Gibson, D.; Haas, H.; Yoshioka, K.; Turgeon, B.G. NPS6, encoding a nonribosomal peptide synthetase involved in siderophore-mediated iron metabolism, is a conserved virulence determinant of plant pathogenic ascomycetes. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 2836–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.N.; Kroken, S.; Chou, D.Y.; Robbertse, B.; Yoder, O.C.; Turgeon, B.G. Functional analysis of all nonribosomal peptide synthetases in Cochliobolus heterostrophus reveals a factor, NPS6, involved in virulence and resistance to oxidative stress. Eukaryot. Cell 2005, 4, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, F.T.; Droce, A.; Sorensen, J.L.; Fojan, P.; Giese, H.; Sondergaard, T.E. Overexpression of NPS4 leads to increased surface hydrophobicity in Fusarium graminearum. Fungal Biol. 2012, 116, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkier, B.A.; Gershenzon, J. Biology and biochemistry of glucosinolates. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2020, 71, 303–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Liu, X.; An, S.; Chang, C.; Zou, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhong, J.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, Z.; Zhou, J.; et al. A nonribosomal peptide synthase containing a stand-alone condensation domain is essential for phytotoxin zeamine biosynthesis. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2013, 26, 1294–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanschen, F.S.; Winkelmann, T. Sulfur volatiles in plant-plant interactions: Ecological and molecular perspectives. Plant Cell Environ. 2023, 46, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrettl, M.; Bignell, E.; Kragl, C.; Sabiha, Y.; Loss, O.; Eisendle, M.; Wallner, A.; Arst, H.N., Jr.; Haynes, K.; Haas, H. Distinct roles for intra-and extracellular siderophores during Aspergillus fumigatus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2007, 3, e128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.J.; Shi, C.; Teitelbaum, A.M.; Gulick, A.M.; Aldrich, C.C. Characterization of AusA: A dimodular nonribosomal peptide synthetase responsible for the production of aureusimine pyrazinones. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 926–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.B.; Baccile, J.A.; Bok, J.W.; Chen, Y.; Keller, N.P.; Schroeder, F.C. A nonribosomal peptide synthetase-derived iron(III) complex from the pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 2064–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, F.T.; Sorensen, J.L.; Giese, H.; Sondergaard, T.E.; Frandsen, R.J. Quick guide to polyketide synthase and nonribosomal synthetase genes in Fusarium. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 155, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunprom, S.; Pongcharoen, P.; Sekito, T.; Kawano-Kawada, M.; Kakinuma, Y.; Akiyama, K. Characterization of vacuolar amino acid transporter from Fusarium oxysporum in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2015, 79, 1972–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramel, C.; Baechler, N.; Hildbrand, M.; Meyer, M.; Schadeli, D.; Dudler, R. Regulation of biosynthesis of syringolin A, a Pseudomonas syringae virulence factor targeting the host proteasome. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2012, 25, 1198–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.H.; Lin, C.H.; Chung, K.R. A nonribosomal peptide synthetase mediates siderophore production and virulence in the citrus fungal pathogen Alternaria alternata. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2013, 14, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, E.P.; Reiber, K.; Neville, C.; Scheibner, O.; Kavanagh, K.; Doyle, S. A nonribosomal peptide synthetase (Pes1) confers protection against oxidative stress in Aspergillus fumigatus. FEBS J. 2006, 273, 3038–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Feng, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X. DEGseq: An R package for identifying differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq data. Bioinformatics 2009, 26, 136–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condon, B.J.; Leng, Y.; Wu, D.; Bushley, K.E.; Ohm, R.A.; Otillar, R.; Martin, J.; Schackwitz, W.; Grimwood, J.; MohdZainudin, N.; et al. Comparative genome structure, secondary metabolite, and effector coding capacity across Cochliobolus pathogens. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Wu, J.; Jiang, J.; Wang, Z.; Ma, Z. Cystathionine gamma-synthase is essential for methionine biosynthesis in Fusarium graminearum. Fungal Biol. 2013, 117, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Ji, F.; Yin, X.; Shi, J. Involvement of threonine deaminase FgIlv1 in isoleucine biosynthesis and full virulence in Fusarium graminearum. Curr. Genet. 2015, 61, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Choi, Y.E.; Zou, X.; Xu, J.R. The FvMK1 mitogen-activated protein kinase gene regulates conidiation, pathogenesis, and fumonisin production in Fusarium verticillioides. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2011, 48, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oide, S.; Berthiller, F.; Wiesenberger, G.; Adam, G.; Turgeon, B.G. Individual and combined roles of malonichrome, ferricrocin, and TAFC siderophores in Fusarium graminearum pathogenic and sexual development. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenczmionka, N.J.; Maier, F.J.; Losch, A.P.; Schafer, W. Mating, conidiation and pathogenicity of Fusarium graminearum, the main causal agent of the head-blight disease of wheat, are regulated by the MAP kinase gpmk1. Curr. Genet. 2003, 43, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, Y.; Sáez-Sandino, T.; Feng, Y.; Yan, X.; He, S.; Feng, S.; Chen, R.; Guo, H.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M. Gemmatirosa adaptations to arid and low soil organic carbon conditions worldwide. Geoderma 2025, 460, 117420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Stupka, E.; Henkel, C.V. Identification of common carp innate immune genes with whole-genome sequencing and RNA-Seq data. J. Integr. Bioinform. 2011, 8, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oide, S.; Krasnoff, S.B.; Turgeon, B.G. NPS6-dependent extracellular siderophores mediate iron acquisition and virulence in Fusarium oxysporum. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.P.; Woltz, S.S. Effect of ethionine and methionine on the growth, sporulation, and virulence of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici race 2. Phytopathology 1969, 59, 1464–1467. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan, K.J.; Dolan, S.K.; Doyle, S. Endogenous cross-talk of fungal metabolites. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenczmionka, N.J.; Schafer, W. The Gpmk1 MAP kinase of Fusarium graminearum regulates the induction of specific secreted enzymes. Curr. Genet. 2005, 47, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| KEGG Categories Represented | Number of Genes | |

|---|---|---|

| WT | ΔFW-NPS6 | |

| Metabolism | 134 | 139 |

| Amino Acid Metabolism | 3 | 2 |

| Biosynthesis of Polyketides and Nonribosomal Peptides | 11 | 12 |

| Biosynthesis of Secondary Metabolites | 40 | 37 |

| Carbohydrate Metabolism | 9 | 14 |

| Energy Metabolism | 21 | 9 |

| Glycan Biosynthesis and Metabolism | 7 | 23 |

| Lipid Metabolism | 12 | 11 |

| Metabolism of Cofactors and Vitamins | 3 | 7 |

| Metabolism of Other Amino Acids | 6 | 9 |

| Nucleotide Metabolism | 10 | 4 |

| Xenobiotics Biodegradation and Metabolism | 13 | 11 |

| Cellular Processes | 236 | 235 |

| Behavior | 1 | 2 |

| Cell Communication | 40 | 45 |

| Cell Growth and Death | 11 | 14 |

| Cell Motility | 15 | 17 |

| Circulatory System | 9 | 10 |

| Development | 60 | 8 |

| Endocrine System | 51 | 53 |

| Immune System | 14 | 60 |

| Nervous System | 3 | 20 |

| Sensory System | 11 | 7 |

| Transport and Catabolism | 21 | 9 |

| Environmental Information Processing | 107 | 108 |

| Membrane Transport | 4 | 6 |

| Signal Transduction | 51 | 62 |

| Signaling Molecules and Interaction | 52 | 40 |

| Genetic Information Processing | 37 | 43 |

| Folding, Sorting and Degradation | 13 | 13 |

| Replication and Repair | 9 | 4 |

| Transcription | 10 | 9 |

| Translation | 5 | 17 |

| Acc. No. Protein Function | RPKM | Fold Change (ΔFW-NPS6 vs. wt) |

|---|---|---|

| Amino acid transport and metabolism | ||

| FOXG_000585 choline dehydrogenase | 82.4 | 0.09 |

| FOXG_000341 peptidylprolyl isomerase | 172.19 | 0.13 |

| FOXG_000647 homoserine O-acetyltransferase | 61.66 | 0.15 |

| FOXG_000604 phosphoserine aminotransferase | 76.75 | 0.26 |

| FOXG_000834 maleylacetoacetate isomerase | 52.19 | 0.35 |

| FOXG_000478 homocitrate synthase | 108.77 | 0.43 |

| FOXG_175961 homoisocitrate dehydrogenase | 55.26 | 4.1 |

| FOXG_168639 glutamate carboxypeptidase II | 30.08 | 4.73 |

| FOXG_000016 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase | 172.18 | 5.55 |

| FOXG_000497 basic amino acid/polyamine antiporter, APA family | 232.64 | 7.35 |

| FOXG_195125 methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase | 47.4 | 8.36 |

| FOXG_134050 cysteine synthase A | 31.19 | 9.24 |

| FOXG_000472 arginine transporter | 80.44 | 10.71 |

| Carbohydrate transport and metabolism | ||

| FOXG_000713 maltose permease | 59.21 | 0.11 |

| FOXG_000094 D-lactate dehydrogenase | 272.84 | 0.19 |

| FOXG_00921 MFS transporter | 43.14 | 0.4 |

| FOXG_134128 Hexokinase | 51.01 | 2.64 |

| FOXG_137571 NAD(P)H-dependent D-xylose reductase (XR) | 43.37 | 2.85 |

| Cell cycle regulation | ||

| FOXG_166060 cell cycle control protein tyrosine phosphatase Mih1 | 54.81 | 7.47 |

| Stress response | ||

| FOXG_000540 zinc-binding oxidoreductase | 228.44 | 3.65 |

| Growth and Survival | ||

| FOXG_000472 osmoregulating MAPK | 112.19 | 0.13 |

| FOXG_001738 TNF receptor-associated factor 6 | 59.48 | 4.37 |

| Fatty acid and lipid transport and metabolism | ||

| FOXG_001664 extracellular lipase | 64.63 | 2.17 |

| FOXG_000190 extracellular lipase | 107.71 | 3.81 |

| FOXG_130515 acyl-CoA-ligases CPS1 | 57.76 | 7.27 |

| Glycan biosynthesis and metabolism | ||

| FOXG_000478 beta-1,6-N-acetylglucosaminyl transferase | 299.58 | 8.56 |

| FOXG_132156 UDP-N-acetylglucosamine pyrophosphorylase | 38.29 | 10.46 |

| Information storage and processing | ||

| FOXG_000540 peptide-N4-(N-acetyl-beta-glucosaminyl)asparagine amidase | 87.3 | 0.1 |

| FOXG_000113 isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase | 208.94 | 0.31 |

| FOXG_132712 alanyl-tRNA synthetase | 35.22 | 5.58 |

| Inorganic ion transport and metabolism | ||

| FOXG_000973 sulfate permease, SulP family | 37.47 | 0.23 |

| FOXG_001733 phosphate-repressible phosphate permease | 61.64 | 2.09 |

| FOXG_137308 metalloreductase Fre8 | 43.79 | 8.47 |

| Sulfur metabolism | ||

| FOXG_128562 choline sulfatase | 57.89 | 3.95 |

| Nitrogen metabolism | ||

| FOXG_00886 cyanide hydratase | 44.19 | 0.47 |

| Metabolism of cofactors | ||

| FOXG_000058 enoyl-CoA hydratase | 290.43 | 0.13 |

| FOXG_000764 type II pantothenate kinase | 55.39 | 0.17 |

| FOXG_001590 similar to Trans-2-enoyl-CoA reductase | 224.92 | 4.26 |

| FOXG_257691 carnitine O-acetyltransferase | 42.21 | 6.36 |

| Nucleotide transport and metabolism | ||

| FOXG_000135 adenine phosphoribosyltransferase | 204.82 | 0.24 |

| Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, folding and assembly | ||

| FOXG_131982 GNAT family acetyltransferase Nat4 | 39.26 | 3.97 |

| FOXG_168639 glutamate carboxypeptidase II | 30.08 | 4.73 |

| Regulation of gene expression | ||

| FOXG_000190 transcriptional adapter 3 | 187.1 | 0.11 |

| FOXG_010129 regulatory protein SWI5 | 33.11 | 0.17 |

| FOXG_001075 translation initiation factor eIF-5A | 33.72 | 0.36 |

| FOXG_000497 translation initiation factor eIF-4 | 107.75 | 0.46 |

| FOXG_165825 small subunit ribosomal protein S2e | 57.39 | 3.95 |

| FOXG_001655 small subunit ribosomal protein S15e | 69.77 | 4.49 |

| FOXG_000047 transcriptional regulatory protein GAL4 | 117.1 | 4.85 |

| FOXG_001610 C6 transcription factor | 72.49 | 5.52 |

| Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism | ||

| FOXG_000637 nonribosomal peptide synthetases 4 | 66.48 | 0.11 |

| FOXG_236772 nonribosomal peptide synthetases 7 | 46.6 | 0.16 |

| FOXG_000786 nonribosomal peptide synthetases 9 | 52.56 | 0.12 |

| FOXG_000578 nonribosomal peptide synthetases 10 | 82.49 | 0.42 |

| FOXG_144903 nonribosomal peptide synthetases 11 | 49.24 | 0.22 |

| FOXG_000848 dimethylallyl tryptophan synthase FtmPTI | 45.86 | 0.11 |

| FOXG_001684 nonribosomal peptide synthetases 2 | 62.48 | 3.32 |

| FOXG 000058 short-chain dehydrogenase | 109.37 | 3.59 |

| Energy production and conversion | ||

| FOXG 001941 AMID-like mitochondrial oxidoreductase | 41.01 | 0.19 |

| FOXG_000027 aarF domain-containing kinase | 117.12 | 3.47 |

| Other | ||

| FOXG_00944 Carboxymethyl ene butenolidase | 39.24 | 0.34 |

| FOXG_000630 membrane dipeptidase | 74.69 | 0.39 |

| FOXG_168476 Bloom syndrome protein | 53.11 | 8.46 |

| FOXG_000341 5-dehydrogenase | 188.09 | 10.46 |

| No. | Gene ID | Gene Name | Primers Sequences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sense 5′-3′ | Anti-Sense 5′-3′ | |||

| a | FOXG_000135 | adenine phosphoribosyltransferase | GACTTGCGCTCCGTCTCGGCGTTC | GACGATCAGCTGCAGCCTTTGC |

| b | FOXG_000472 | osmoregulating MAPK | GCCCGATATCAACATCTCGTGG | GCATTCAGCTTCTAGCTTGAAATC |

| c | FOXG_00886 | cyanide hydratase | CGTGAGAACTCCATGGCTGTCGAC | GATGACAGCACCGTCAGGACCGA |

| d | FOXG_001075 | translation initiation factor eIF-5A | CCGTTCTCTTCAAAGAACTCGA | GGTGTCACCGTCATCGGTCATG |

| e | FOXG_000047 | transcriptional regulatory protein GAL4 | GCAAGCATCTCGGCTTGCAA | GCTCTTGGAAGACCTGCTCG |

| f | FOXG_001684 | nonribosomal peptide synthetases 2 | CTCTGAACATCGACGCACC | ATGGAATATGTCTGTCGTG |

| g | FOXG_001610 | C6 transcription factor | GGTATGGATCCACAATACC | GGCGCATGATGGTTGTTTC |

| h | FOXG_130515 | acyl-CoA-ligases CPS1 | CGCCTCTCAACCCGGCTTACAAG | TGATAAGACGTACTCATGGTTCG |

| Reference | GenBank: U37499.1 | β-actinI | GCGTGACATCAAGGAGAAGC | TGGGCAACGGAACCTCT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ye, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Lu, H.; Li, J.; Zou, H. ΔFW-NPS6-Dependent Transcriptome Profiling Reveals Putative Pathogenicity Genes in Fusarium oxysporum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 830. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020830

Ye X, Zhang L, Zhang J, Lu H, Li J, Zou H. ΔFW-NPS6-Dependent Transcriptome Profiling Reveals Putative Pathogenicity Genes in Fusarium oxysporum. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):830. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020830

Chicago/Turabian StyleYe, Xuhong, Li Zhang, Jianjie Zhang, Haozhe Lu, Jiaqi Li, and Hongtao Zou. 2026. "ΔFW-NPS6-Dependent Transcriptome Profiling Reveals Putative Pathogenicity Genes in Fusarium oxysporum" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 830. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020830

APA StyleYe, X., Zhang, L., Zhang, J., Lu, H., Li, J., & Zou, H. (2026). ΔFW-NPS6-Dependent Transcriptome Profiling Reveals Putative Pathogenicity Genes in Fusarium oxysporum. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 830. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020830