RNA-Binding Proteins in Adipose Biology: From Mechanistic Understanding to Therapeutic Opportunities

Abstract

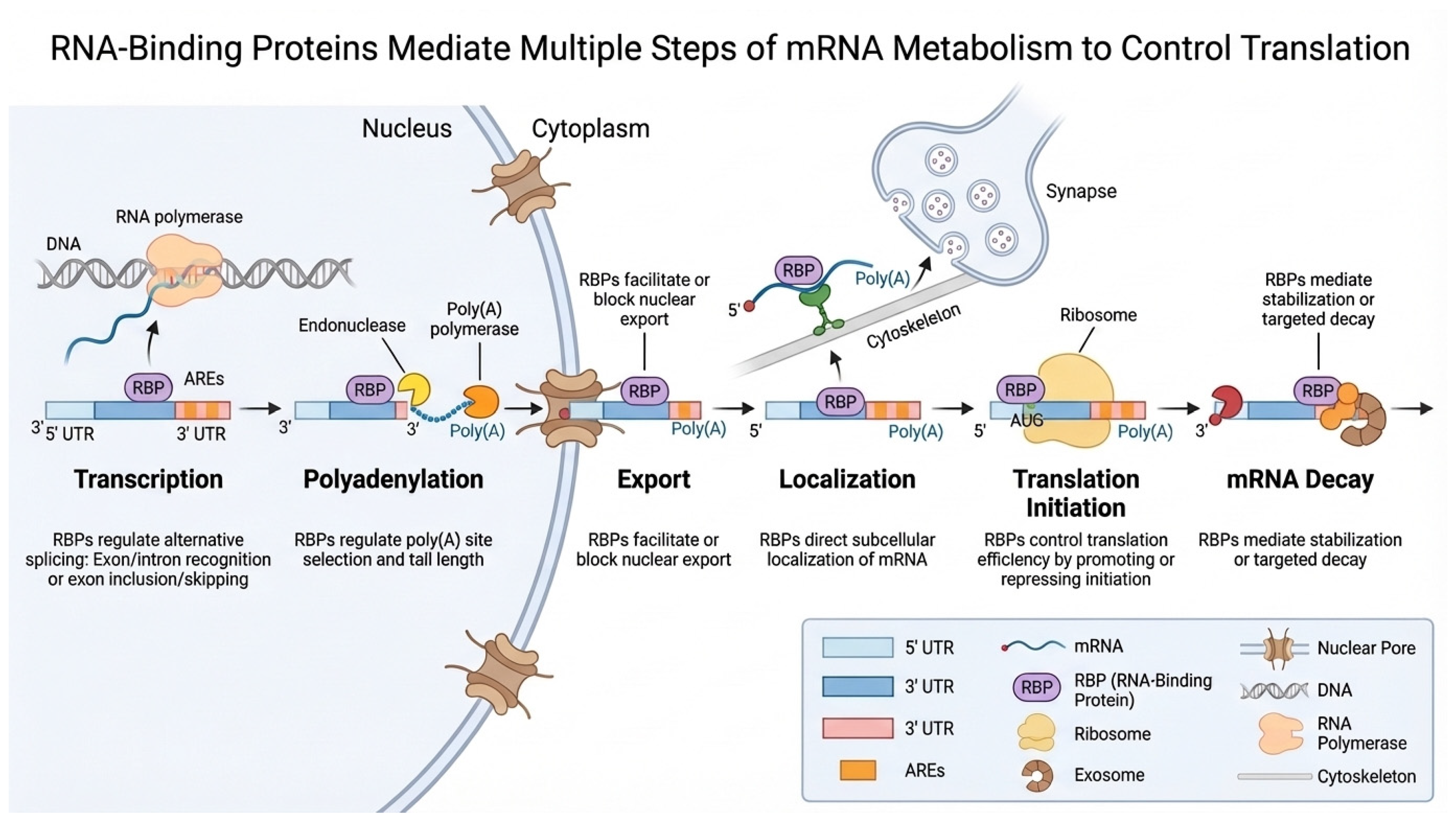

1. Introduction

2. Regulatory Controls of Adipogenesis and Adipose Tissue Function

3. RNA-Binding Proteins in the Regulation of Adipogenesis and Adipose Metabolism

3.1. Quaking Protein (QKI)

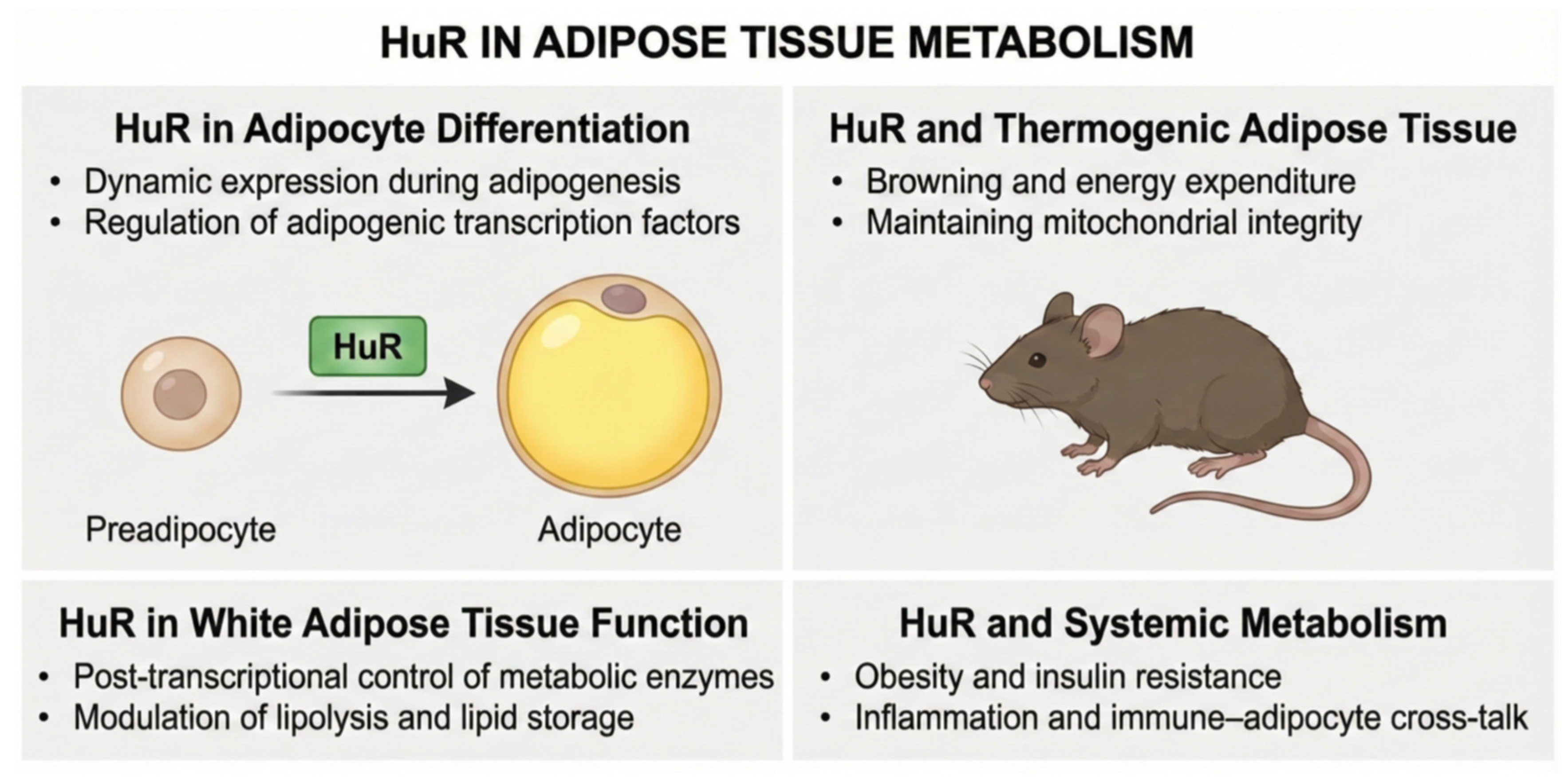

3.2. HuR (Human Antigen R)

3.3. Y-Box Binding Proteins

3.4. CELF1 (CUG-Binding Protein 1)

3.5. IGF2BP1 (Insulin-like Growth Factor 2 mRNA-Binding Protein 1)

3.6. ZFP36 (Zinc Finger Protein 36 Homolog)

3.7. CPEB4 (Cytoplasmic Polyadenylation Element Binding Protein 4)

3.8. HNRNPA1 (Heterogeneous Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein A1)

3.9. HnRNPA2B1 (Heterogeneous Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein A2/B1)

3.10. PSPC1 (Paraspeckle Component 1)

3.11. RBMS1 (RNA-Binding Motif Single-Stranded Interacting Protein 1)

3.12. MEX3C (Mex-3 RNA Binding Family Member C)

3.13. PCBP2 (Poly(rC)-Binding Protein 2)

3.14. Sam68

4. Emerging Therapeutic Approaches to Target RNA-Binding Proteins

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RBP | RNA-binding protein |

| QKI | Quaking |

| WAT | White adipose tissue |

| BAT | Brown adipose tissue |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma |

| HuR | Human antigen R |

| BMI | Body mass index |

References

- Verma, S.; Hussain, M.E. Obesity and Diabetes: An Update. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2017, 11, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauder, K.A.; Ritchie, N.D. Reducing Intergenerational Obesity and Diabetes Risk. Diabetologia 2021, 64, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meldrum, D.R.; Morris, M.A.; Gambone, J.C. Obesity Pandemic: Causes, Consequences, and Solutions—But Do We Have the Will? Fertil. Steril. 2017, 107, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blüher, M. An Overview of Obesity-related Complications: The Epidemiological Evidence Linking Body Weight and Other Markers of Obesity to Adverse Health Outcomes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingram, Y.; Olujide, O.; Sheikh, N.; Robinson, A.; Ho, J.H.; Syed, A.A.; Adam, S. The Relationship Between Obesity and Cancer: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and the Effect of Obesity Treatment on Cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pati, S.; Irfan, W.; Jameel, A.; Ahmed, S.; Shahid, R.K. Obesity and Cancer: A Current Overview of Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Outcomes, and Management. Cancers 2023, 15, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, S.; Haboubi, H.; Haboubi, N. Adult Obesity Complications: Challenges and Clinical Impact. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 11, 2042018820934955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M.; Adair, L.S.; Ng, S.W. Global Nutrition Transition and the Pandemic of Obesity in Developing Countries. Nutr. Rev. 2012, 70, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinburn, B.A.; Sacks, G.; Hall, K.D.; McPherson, K.; Finegood, D.T.; Moodie, M.L.; Gortmaker, S.L. The Global Obesity Pandemic: Shaped by Global Drivers and Local Environments. Lancet 2011, 378, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecker, J.; Freijer, K.; Hiligsmann, M.; Evers, S.M.A.A. Burden of Disease Study of Overweight and Obesity; the Societal Impact in Terms of Cost-of-Illness and Health-Related Quality of Life. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leutner, M.; Dervic, E.; Bellach, L.; Klimek, P.; Thurner, S.; Kautzky, A. Obesity as Pleiotropic Risk State for Metabolic and Mental Health throughout Life. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalle Grave, R. The Benefit of Healthy Lifestyle in the Era of New Medications to Treat Obesity. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2024, 17, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadden, T.A.; Tronieri, J.S.; Butryn, M.L. Lifestyle Modification Approaches for the Treatment of Obesity in Adults. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, M.; Oliveira, T.; Fernandes, R. Biochemistry of Adipose Tissue: An Endocrine Organ. Arch. Med. Sci. 2013, 9, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Liu, M. Adipose Tissue in Control of Metabolism. J. Endocrinol. 2016, 231, R77–R99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragoo, J.L.; Shapiro, S.A.; Bradsell, H.; Frank, R.M. The Essential Roles of Human Adipose Tissue: Metabolic, Thermoregulatory, Cellular, and Paracrine Effects. J. Cartil. Jt. Preserv. 2021, 1, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigolet, M.E.; Gutiérrez-Aguilar, R. The Colors of Adipose Tissue. Gac. Med. Mex. 2020, 156, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, B.; Nedergaard, J. Brown Adipose Tissue: Function and Physiological Significance. Physiol. Rev. 2004, 84, 277–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, B.; Li, M.; Speakman, J.R. Switching on the Furnace: Regulation of Heat Production in Brown Adipose Tissue. Mol. Asp. Med. 2019, 68, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negroiu, C.E.; Tudorașcu, I.; Bezna, C.M.; Godeanu, S.; Diaconu, M.; Danoiu, R.; Danoiu, S. Beyond the Cold: Activating Brown Adipose Tissue as an Approach to Combat Obesity. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifarelli, V.; Beeman, S.C.; Smith, G.I.; Yoshino, J.; Morozov, D.; Beals, J.W.; Kayser, B.D.; Watrous, J.D.; Jain, M.; Patterson, B.W.; et al. Decreased Adipose Tissue Oxygenation Associates with Insulin Resistance in Individuals with Obesity. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 6688–6699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, M.; Zatterale, F.; Naderi, J.; Parrillo, L.; Formisano, P.; Raciti, G.A.; Beguinot, F.; Miele, C. Adipose Tissue Dysfunction as Determinant of Obesity-Associated Metabolic Complications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajer, G.R.; Van Haeften, T.W.; Visseren, F.L.J. Adipose Tissue Dysfunction in Obesity, Diabetes, and Vascular Diseases. Eur. Heart J. 2008, 29, 2959–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai, T.; Autieri, M.V.; Scalia, R. Adipose Tissue Inflammation and Metabolic Dysfunction in Obesity. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2021, 320, C375–C391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, L.; Wanasinghe, A.I.; Brunori, P.; Santosa, S. Is Adipose Tissue Inflammation the Culprit of Obesity-Associated Comorbidities? Obes. Rev. 2025, 26, e13956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatterale, F.; Longo, M.; Naderi, J.; Raciti, G.A.; Desiderio, A.; Miele, C.; Beguinot, F. Chronic Adipose Tissue Inflammation Linking Obesity to Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes. Front. Physiol. 2020, 10, 1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yun, K.; Mu, R. A Review on the Biology and Properties of Adipose Tissue Macrophages Involved in Adipose Tissue Physiological and Pathophysiological Processes. Lipids Health Dis. 2020, 19, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, S.S.; Huh, J.Y.; Hwang, I.J.; Kim, J.I.; Kim, J.B. Adipose Tissue Remodeling: Its Role in Energy Metabolism and Metabolic Disorders. Front. Endocrinol. 2016, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, C.E.; O’Rahilly, S.; Rochford, J.J. Adipogenesis at a Glance. J. Cell Sci. 2011, 124, 2681–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakab, J.; Miškić, B.; Mikšić, Š.; Juranić, B.; Ćosić, V.; Schwarz, D.; Včev, A. Adipogenesis as a Potential Anti-Obesity Target: A Review of Pharmacological Treatment and Natural Products. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2021, 14, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambele, M.A.; Dhanraj, P.; Giles, R.; Pepper, M.S. Adipogenesis: A Complex Interplay of Multiple Molecular Determinants and Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, E.D.; Walkey, C.J.; Puigserver, P.; Spiegelman, B.M. Transcriptional Regulation of Adipogenesis. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 1293–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siersbæk, R.; Nielsen, R.; Mandrup, S. PPARγ in Adipocyte Differentiation and Metabolism—Novel Insights from Genome-wide Studies. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 3242–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farmer, S.R. Regulation of PPARγ Activity during Adipogenesis. Int. J. Obes. 2005, 29, S13–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefterova, M.I.; Haakonsson, A.K.; Lazar, M.A.; Mandrup, S. PPARγ and the Global Map of Adipogenesis and Beyond. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 25, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hishida, T.; Nishizuka, M.; Osada, S.; Imagawa, M. The Role of C/EBPδ in the Early Stages of Adipogenesis. Biochimie 2009, 91, 654–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, L.E.; Orho-Melander, M.; William-Olsson, L.; Sjöholm, K.; Sjöström, L.; Groop, L.; Carlsson, B.; Carlsson, L.M.S.; Olsson, B. CCAAT/Enhancer Binding Protein α (C/EBPα) in Adipose Tissue Regulates Genes in Lipid and Glucose Metabolism and a Genetic Variation in C/EBPα Is Associated with Serum Levels of Triglycerides. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 93, 4880–4886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-Y.; Jang, H.-J.; Muthamil, S.; Shin, U.C.; Lyu, J.-H.; Kim, S.-W.; Go, Y.; Park, S.-H.; Lee, H.G.; Park, J.H. Novel Insights into Regulators and Functional Modulators of Adipogenesis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 177, 117073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, S.; Peng, J. Novel Insights into Adipogenesis from the Perspective of Transcriptional and RNA N6-Methyladenosine-Mediated Post-Transcriptional Regulation. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 2001563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squillaro, T.; Peluso, G.; Galderisi, U.; Di Bernardo, G. Long Non-Coding RNAs in Regulation of Adipogenesis and Adipose Tissue Function. Elife 2020, 9, e59053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-J.; Choo, K.B. Circular RNA- and MicroRNA-Mediated Post-Transcriptional Regulation of Preadipocyte Differentiation in Adipogenesis: From Expression Profiling to Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naing, Y.T.; Sun, L. The Role of Splicing Factors in Adipogenesis and Thermogenesis. Mol. Cells 2023, 46, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Wu, W.; Ma, C.; Du, C.; Huang, Y.; Xu, H.; Li, C.; Cheng, X.; Hao, R.; Xu, Y. RNA-Binding Proteins in the Regulation of Adipogenesis and Adipose Function. Cells 2022, 11, 2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anghel, S.I.; Wahli, W. Fat Poetry: A Kingdom for PPARγ. Cell Res. 2007, 17, 486–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Mao, S.; Chen, S.; Zhang, W.; Liu, C. PPARs-Orchestrated Metabolic Homeostasis in the Adipose Tissue. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, R.; Bhattacharya, P.; Gavrilova, O.; Glass, K.; Moitra, J.; Myakishev, M.; Pack, S.; Jou, W.; Feigenbaum, L.; Eckhaus, M.; et al. Suppression of the C/EBP Family of Transcription Factors in Adipose Tissue Causes Lipodystrophy. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2011, 46, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; MacLean, P.S.; Schaack, J.; Orlicky, D.J.; Darimont, C.; Pagliassotti, M.; Friedman, J.E.; Shao, J. C/EBPα Regulates Human Adiponectin Gene Transcription Through an Intronic Enhancer. Diabetes 2005, 54, 1744–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseti, D.; Regassa, A.; Kim, W.-K. Molecular Regulation of Adipogenesis and Potential Anti-Adipogenic Bioactive Molecules. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.; Wang, W.; Tu, M.; Zhao, B.; Han, J.; Li, J.; Pan, Y.; Zhou, J.; Ma, W.; Liu, Y.; et al. Deciphering Adipose Development: Function, Differentiation and Regulation. Dev. Dyn. 2024, 253, 956–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C.; Durandt, C.; Kallmeyer, K.; Ambele, M.A.; Pepper, M.S. The Role of Pref-1 during Adipogenic Differentiation: An Overview of Suggested Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Q.; Dalgin, G.; Xu, H.; Ting, C.-N.; Leiden, J.M.; Hotamisligil, G.S. Function of GATA Transcription Factors in Preadipocyte-Adipocyte Transition. Science 2000, 290, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Li, X.; Zhai, J.; Lu, C.; Yu, W.; Wu, W.; Chen, J. Orchestrating Nutrient Homeostasis: RNA-Binding Proteins as Molecular Conductors in Metabolic Disease Pathogenesis. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotamisligil, G. Molecular Mechanisms of Insulin Resistance and the Role of the Adipocyte. Int. J. Obes. 2000, 24, S23–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Itoh, M.; Ogawa, Y.; Suganami, T. Molecular Mechanism of Obesity-induced ‘Metabolic’ Tissue Remodeling. J. Diabetes Investig. 2018, 9, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Z.; Chen, J.; Chen, F.; Guan, W.; Zhang, S. Regulation of the JAK2-STAT5 Pathway by Signaling Molecules in the Mammary Gland. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 604896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurylowicz, A. MicroRNAs in Human Adipose Tissue Physiology and Dysfunction. Cells 2021, 10, 3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hentze, M.W.; Castello, A.; Schwarzl, T.; Preiss, T. A Brave New World of RNA-Binding Proteins. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corley, M.; Burns, M.C.; Yeo, G.W. How RNA-Binding Proteins Interact with RNA: Molecules and Mechanisms. Mol. Cell 2020, 78, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Xu, N. Insights into the Mode and Mechanism of Interactions Between RNA and RNA-Binding Proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, B.; Billaud, M.; Almeida, R. RNA-Binding Proteins in Cancer: Old Players and New Actors. Trends Cancer 2017, 3, 506–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Chu, J.; An, S.; Liu, X.; Tan, R. The Biological Mechanisms and Clinical Roles of RNA-Binding Proteins in Cardiovascular Diseases. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelaini, S.; Chan, C.; Cornelius, V.A.; Margariti, A. RNA-Binding Proteins Hold Key Roles in Function, Dysfunction, and Disease. Biology 2021, 10, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maziuk, B.; Ballance, H.I.; Wolozin, B. Dysregulation of RNA Binding Protein Aggregation in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, J.-Y.; Yang, B.; Shi, C.-P.; Deng, W.-X.; Deng, J.-S.; Cen, M.-F.; Zheng, B.-Q.; Zhan, Z.-L.; Liang, Q.-L.; Wang, J.-E.; et al. RBPWorld for Exploring Functions and Disease Associations of RNA-Binding Proteins across Species. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D220–D232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukong, K.E.; Chang, K.; Khandjian, E.W.; Richard, S. RNA-Binding Proteins in Human Genetic Disease. Trends Genet. 2008, 24, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Xu, L. The RNA-Binding Protein HuR in Human Cancer: A Friend or Foe? Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2022, 184, 114179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnieri, A.R.; Anthony, S.R.; Gozdiff, A.; Green, L.C.; Fleifil, S.M.; Slone, S.; Nieman, M.L.; Alam, P.; Benoit, J.B.; Owens, A.P.; et al. Adipocyte-Specific Deletion of HuR Induces Spontaneous Cardiac Hypertrophy and Fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2021, 321, H228–H241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, P.; Wang, R.; Tang, T.; Qi, K. Adipose-Specific HuR Deletion Protects against High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity in Mice through Upregulating Ucp1 Expression. Lipids Health Dis. 2025, 24, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordovkina, D.; Lyabin, D.N.; Smolin, E.A.; Sogorina, E.M.; Ovchinnikov, L.P.; Eliseeva, I. Y-Box Binding Proteins in MRNP Assembly, Translation, and Stability Control. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Wang, W. YBX1: A Multifunctional Protein in Senescence and Immune Regulation. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 14058–14079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleene, K.C. Y-Box Proteins Combine Versatile Cold Shock Domains and Arginine-Rich Motifs (ARMs) for Pleiotropic Functions in RNA Biology. Biochem. J. 2018, 475, 2769–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Zeng, F.; Lei, Y.; Li, Y.; Deng, J.; Luo, G.; He, Q.; Zhou, Y. YBX1: An RNA/DNA-Binding Protein That Affects Disease Progression. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1635209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.; Xu, S.; Kyaw, A.M.M.; Lim, Y.C.; Chia, S.Y.; Chee Siang, D.T.; Alvarez-Dominguez, J.R.; Chen, P.; Leow, M.K.-S.; Sun, L. RNA Binding Protein Ybx2 Regulates RNA Stability During Cold-Induced Brown Fat Activation. Diabetes 2017, 66, 2987–3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Yu, C.; Xu, X.; Jin, W.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, H.; Gao, Y.; Pan, D. Phosphorylated YBX2 Is Stabilized to Promote Glycolysis in Brown Adipocytes. iScience 2023, 26, 108091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Shi, J.-J.; Chen, R.-Y.; Li, C.-Y.; Liu, Y.-J.; Lu, J.-F.; Yang, G.-J.; Cao, J.-F.; Chen, J. Curriculum Vitae of CUG Binding Protein 1 (CELF1) in Homeostasis and Diseases: A Systematic Review. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2024, 29, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, J.; Lee, J.E.; López, C.M.; Anderson, J.; Nguyen, T.P.; Heck, A.M.; Wilusz, J.; Wilusz, C.J. The CELF1 RNA-Binding Protein Regulates Decay of Signal Recognition Particle MRNAs and Limits Secretion in Mouse Myoblasts. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhury, A.; Cheema, S.; Fachini, J.M.; Kongchan, N.; Lu, G.; Simon, L.M.; Wang, T.; Mao, S.; Rosen, D.G.; Ittmann, M.M.; et al. CELF1 Is a Central Node in Post-Transcriptional Regulatory Programmes Underlying EMT. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinney, A.; Albayrak, Ö.; Antel, J.; Volckmar, A.; Sims, R.; Chapman, J.; Harold, D.; Gerrish, A.; Heid, I.M.; Winkler, T.W.; et al. Genetic Variation at the CELF1 (CUGBP, Elav-like Family Member 1 Gene) Locus Is Genome-wide Associated with Alzheimer’s Disease and Obesity. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2014, 165, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagiannides, I.; Thomou, T.; Tchkonia, T.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Kypreos, K.E.; Cartwright, A.; Dalagiorgou, G.; Lash, T.L.; Farmer, S.R.; Timchenko, N.A.; et al. Increased CUG Triplet Repeat-Binding Protein-1 Predisposes to Impaired Adipogenesis with Aging. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 23025–23033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, T.; Xiao, L.; Li, J.; Wu, H.; Guo, X.; Zhu, F.; Yu, X.; Cui, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; et al. Adipocyte RNA-Binding Protein CELF1 Promotes Beiging of White Fat through Stabilizing Dio2 MRNA. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Day, F.R.; Gustafsson, S.; Buchkovich, M.L.; Na, J.; Bataille, V.; Cousminer, D.L.; Dastani, Z.; Drong, A.W.; Esko, T.; et al. New Loci for Body Fat Percentage Reveal Link between Adiposity and Cardiometabolic Disease Risk. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crujeiras, A.B.; Diaz-Lagares, A.; Moreno-Navarrete, J.M.; Sandoval, J.; Hervas, D.; Gomez, A.; Ricart, W.; Casanueva, F.F.; Esteller, M.; Fernandez-Real, J.M. Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Pattern in Visceral Adipose Tissue Differentiates Insulin-Resistant from Insulin-Sensitive Obese Subjects. Transl. Res. 2016, 178, 13–24.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Wang, F.; Sheng, Y.; Xia, F.; Jin, Y.; Ding, G.; Wang, X.; Yu, J. Estrogen Supplementation Deteriorates Visceral Adipose Function in Aged Postmenopausal Subjects via Gas5 Targeting IGF2BP1. Exp. Gerontol. 2022, 163, 111796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouchard, L.; Tchernof, A.; Deshaies, Y.; Marceau, S.; Lescelleur, O.; Biron, S.; Vohl, M.-C. ZFP36: A Promising Candidate Gene for Obesity-Related Metabolic Complications Identified by Converging Genomics. Obes. Surg. 2007, 17, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Hai, J.; Ti, Y.; Kong, B.; Yao, G.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, C.; Ma, X.; et al. Adipose ZFP36 Protects against Diet-Induced Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Metabolism 2025, 164, 156131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajuthi, S.P.; Sharma, N.K.; Chou, J.W.; Palmer, N.D.; McWilliams, D.R.; Beal, J.; Comeau, M.E.; Ma, L.; Calles-Escandon, J.; Demons, J.; et al. Mapping Adipose and Muscle Tissue Expression Quantitative Trait Loci in African Americans to Identify Genes for Type 2 Diabetes and Obesity. Hum. Genet. 2016, 135, 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pell, N.; Garcia-Pras, E.; Gallego, J.; Naranjo-Suarez, S.; Balvey, A.; Suñer, C.; Fernandez-Alfara, M.; Chanes, V.; Carbo, J.; Ramirez-Pedraza, M.; et al. Targeting the Cytoplasmic Polyadenylation Element-Binding Protein CPEB4 Protects against Diet-Induced Obesity and Microbiome Dysbiosis. Mol. Metab. 2021, 54, 101388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Su, Y.; Xu, Y.; Hu, T.; Lu, X.; Sun, J.; Li, W.; Zhou, J.; Ma, X.; Yang, Y.; et al. Adipocyte-Specific Hnrnpa1 Knockout Aggravates Obesity-Induced Metabolic Dysfunction via Upregulation of CCL2. Diabetes 2024, 73, 713–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, D.; Ping, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wang, L.; Jin, L.; Zhao, W.; Guo, M.; Shen, F.; et al. Local Hyperthermia Therapy Induces Browning of White Fat and Treats Obesity. Cell 2022, 185, 949–966.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, M.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, D.; Li, D.; Xu, L.; Ma, X. HnRNPA2B1 Aggravates Inflammation by Promoting M1 Macrophage Polarization. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunez Lopez, Y.O.; Casu, A.; Kovacova, Z.; Petrilli, A.M.; Sideleva, O.; Tharp, W.G.; Pratley, R.E. Coordinated Regulation of Gene Expression and MicroRNA Changes in Adipose Tissue and Circulating Extracellular Vesicles in Response to Pioglitazone Treatment in Humans with Type 2 Diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 955593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Rajbhandari, P.; Damianov, A.; Han, A.; Sallam, T.; Waki, H.; Villanueva, C.J.; Lee, S.D.; Nielsen, R.; Mandrup, S.; et al. RNA-Binding Protein PSPC1 Promotes the Differentiation-Dependent Nuclear Export of Adipocyte RNAs. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 987–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazakova, E.; Chen, M.; Jamaspishvili, E.; Lin, Z.; Yu, J.; Sun, L.; Qiao, H. Association between RBMS1 Gene Rs7593730 and BCAR1 Gene Rs7202877 and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in a Chinese Han Population. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2018, 65, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, L.; Cornelis, M.C.; Kraft, P.; Stanya, K.J.; Linda Kao, W.H.; Pankow, J.S.; Dupuis, J.; Florez, J.C.; Fox, C.S.; Paré, G.; et al. Genetic Variants at 2q24 Are Associated with Susceptibility to Type 2 Diabetes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010, 19, 2706–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dairi, G.; Al Mahri, S.; Benabdelkamel, H.; Alfadda, A.A.; Alswaji, A.A.; Rashid, M.; Malik, S.S.; Iqbal, J.; Ali, R.; Al Ibrahim, M.; et al. Transcriptomic and Proteomic Analysis Reveals the Potential Role of RBMS1 in Adipogenesis and Adipocyte Metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, Y.; George, S.K.; Zhao, Q.; Hulver, M.W.; Hutson, S.M.; Bishop, C.E.; Lu, B. Mex3c Mutation Reduces Adiposity and Increases Energy Expenditure. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2012, 32, 4350–4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuniyoshi, K.; Takeuchi, O.; Pandey, S.; Satoh, T.; Iwasaki, H.; Akira, S.; Kawai, T. Pivotal Role of RNA-Binding E3 Ubiquitin Ligase MEX3C in RIG-I–Mediated Antiviral Innate Immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 5646–5651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluscevic, M.; Paradise, C.R.; Dudakovic, A.; Karperien, M.; Dietz, A.B.; van Wijnen, A.J.; Deyle, D.R. Functional Expression of ZNF467 and PCBP2 Supports Adipogenic Lineage Commitment in Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Gene 2020, 737, 144437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huot, M.-É.; Vogel, G.; Zabarauskas, A.; Ngo, C.T.-A.; Coulombe-Huntington, J.; Majewski, J.; Richard, S. The Sam68 STAR RNA-Binding Protein Regulates MTOR Alternative Splicing during Adipogenesis. Mol. Cell 2012, 46, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Cheng, M.; Boriboun, C.; Ardehali, M.M.; Jiang, C.; Liu, Q.; Han, S.; Goukassian, D.A.; Tang, Y.-L.; Zhao, T.C.; et al. Inhibition of Sam68 Triggers Adipose Tissue Browning. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 225, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, A.; Ma, W.; Deng, J.; Zhou, J.; Han, C.; Zhang, E.; Boriboun, C.; Xu, S.; Zhang, C.; Jie, C.; et al. Ablation of Sam68 in Adult Mice Increases Thermogenesis and Energy Expenditure. FASEB J. 2021, 35, e21772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilariño-García, T.; Guadix, P.; Dorado-Silva, M.; Sánchez-Martín, P.; Pérez-Pérez, A.; Sánchez-Margalet, V. Decreased Expression of Sam68 Is Associated with Insulin Resistance in Granulosa Cells from PCOS Patients. Cells 2022, 11, 2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pérez, A.; Sánchez-Jiménez, F.; Vilariño-García, T.; de la Cruz, L.; Virizuela, J.A.; Sánchez-Margalet, V. Sam68 Mediates the Activation of Insulin and Leptin Signalling in Breast Cancer Cells. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Veer, E.P.; de Bruin, R.G.; Kraaijeveld, A.O.; de Vries, M.R.; Bot, I.; Pera, T.; Segers, F.M.; Trompet, S.; van Gils, J.M.; Roeten, M.K.; et al. Quaking, an RNA-Binding Protein, Is a Critical Regulator of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Phenotype. Circ. Res. 2013, 113, 1065–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edatt, L.; Li, D.; Dudley, A.C.; Pecot, C.V. Diverse Roles of Quaking in Endothelial Cell Biology. Angiogenesis 2025, 29, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Yang, W.; Sun, G.; Huang, J. RNA-Binding Protein Quaking: A Multifunctional Regulator in Tumour Progression. Ann. Med. 2025, 57, 2443046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artzt, K.; Wu, J.I. STAR Trek: An Introduction to STAR Family Proteins and Review of Quaking (QKI). Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010, 693, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Galarneau, A.; Richard, S. Target RNA Motif and Target MRNAs of the Quaking STAR Protein. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005, 12, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yin, J.; Cao, D.; Xiao, D.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, Y.; Shou, W. The Emerging Roles of the RNA Binding Protein QKI in Cardiovascular Development and Function. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 668659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, D.P.; Goodall, G.J.; Gregory, P.A. The Quaking RNA-binding Proteins as Regulators of Cell Differentiation. WIREs RNA 2022, 13, e1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Chu, C.; Li, X.; Gu, S.; Zou, Q.; Jin, Y. RNA-Binding Protein QKI Suppresses Breast Cancer via RASA1/MAPK Signaling Pathway. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zong, F.-Y.; Fu, X.; Wei, W.-J.; Luo, Y.-G.; Heiner, M.; Cao, L.-J.; Fang, Z.; Fang, R.; Lu, D.; Ji, H.; et al. The RNA-Binding Protein QKI Suppresses Cancer-Associated Aberrant Splicing. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandesh, K.; Prasad, G.; Giri, A.K.; Kauser, Y.; Upadhyay, M.; Basu, A.; Tandon, N.; Bharadwaj, D. Genome-Wide Association Study of Blood Lipids in Indians Confirms Universality of Established Variants. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 64, 573–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; He, C.; Ren, J.; Dai, C.; Stevens, S.R.; Wang, Q.; Zamler, D.; Shingu, T.; Yuan, L.; Chandregowda, C.R.; et al. Mature Myelin Maintenance Requires Qki to Coactivate PPARβ-RXRα-Mediated Lipid Metabolism. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 2220–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Sun, Y.; Liu, W.; Dong, J.; Chen, J. SIRT1 Mediates the Role of RNA-Binding Protein QKI 5 in the Synthesis of Triglycerides in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Mice via the PPARα/FoxO1 Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 43, 1271–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Ye, Z.; Zhai, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Luo, W.; Lu, Z.; Chen, J. QKI Regulates Adipose Tissue Metabolism by Acting as a Brake on Thermogenesis and Promoting Obesity. EMBO Rep. 2020, 21, e47929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachiondo-Ortega, S.; Delgado, T.C.; Baños-Jaime, B.; Velázquez-Cruz, A.; Díaz-Moreno, I.; Martínez-Chantar, M.L. Hu Antigen R (HuR) Protein Structure, Function and Regulation in Hepatobiliary Tumors. Cancers 2022, 14, 2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, M.; Chakraborty, P.; Mohan, S.; Mehrotra, S.; Palanisamy, V. HuR as a Molecular Target for Cancer Therapeutics and Immune-Related Disorders. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2022, 188, 114442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppler, N.; Jones, E.; Ahamed, F.; Zhang, Y. Multifaceted Human Antigen R (HuR): A Key Player in Liver Metabolism and MASLD. Livers 2025, 5, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goutas, D.; Pergaris, A.; Giaginis, C.; Theocharis, S. HuR as Therapeutic Target in Cancer: What the Future Holds. Curr. Med. Chem. 2022, 29, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Kim, S.H.; Armaly, A.M.; Aubé, J.; Xu, L.; Wu, X. RNA-Binding Protein HuR Inhibition Induces Multiple Programmed Cell Death in Breast and Prostate Cancer. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzeszutek, I.; Nowak-Król, A. HuR-Targeted Small-Molecule Inhibitors—Beneficial Impact in Cancer Therapy. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 68, 22009–22032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, C.; Liu, J.; Xie, M.; Chen, X.; Dixon, D.A.; Wu, X.; Yang, L. Post-Transcriptional Regulation by HuR in Colorectal Cancer: Impacts on Tumor Progression and Therapeutic Strategies. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1658526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatti da Silva, G.H.; Pereira Dos Santos, M.G.; Nagasse, H.Y.; Pereira Coltri, P. Human Antigen R (HuR) Facilitates MiR-19 Synthesis and Affects Cellular Kinetics in Papillary Thyroid Cancer. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 56, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finan, J.M.; Sutton, T.L.; Dixon, D.A.; Brody, J.R. Targeting the RNA-Binding Protein HuR in Cancer. Cancer Res. 2023, 83, 3507–3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.E.; Kipchumba, R. HuR Brings the Heat: Linking Adipose Tissue to Cardiac Dysfunction. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2021, 321, H214–H216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnieri, A.R.; Anthony, S.; Tranter, M. HuR Mediates Thermogenic Metabolism in Brown Adipose Tissue Through Control of Sarco-Endoplasmic Calcium Cycling. FASEB J. 2022, 36, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Gong, L.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Tian, M.; Lu, H.; Bu, P.; Yang, J.; Ouyang, C.; et al. Adipose HuR Protects against Diet-Induced Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siang, D.T.C.; Lim, Y.C.; Kyaw, A.M.M.; Win, K.N.; Chia, S.Y.; Degirmenci, U.; Hu, X.; Tan, B.C.; Walet, A.C.E.; Sun, L.; et al. The RNA-Binding Protein HuR Is a Negative Regulator in Adipogenesis. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantt, K.; Cherry, J.; Tenney, R.; Karschner, V.; Pekala, P.H. An Early Event in Adipogenesis, the Nuclear Selection of the CCAAT Enhancer-Binding Protein β (C/EBPβ) MRNA by HuR and Its Translocation to the Cytosol. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 24768–24774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, S.R.; Guarnieri, A.; Lanzillotta, L.; Gozdiff, A.; Green, L.C.; O’Grady, K.; Helsley, R.N.; Owens, A.P.; Tranter, M. HuR Expression in Adipose Tissue Mediates Energy Expenditure and Acute Thermogenesis Independent of UCP1 Expression. Adipocyte 2020, 9, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.; Feng, S.; Li, F.; Shu, G.; Wang, L.; Gao, P.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, C.; Wang, S.; Jiang, Q. Transcriptional and Post-Transcriptional Control of Autophagy and Adipogenesis by YBX1. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakaguchi, M.; Okagawa, S.; Okubo, Y.; Otsuka, Y.; Fukuda, K.; Igata, M.; Kondo, T.; Sato, Y.; Yoshizawa, T.; Fukuda, T.; et al. Phosphatase Protector Alpha4 (A4) Is Involved in Adipocyte Maintenance and Mitochondrial Homeostasis through Regulation of Insulin Signaling. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabiee, A.; Plucińska, K.; Isidor, M.S.; Brown, E.L.; Tozzi, M.; Sidoli, S.; Petersen, P.S.S.; Agueda-Oyarzabal, M.; Torsetnes, S.B.; Chehabi, G.N.; et al. White Adipose Remodeling during Browning in Mice Involves YBX1 to Drive Thermogenic Commitment. Mol. Metab. 2021, 44, 101137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Cao, S.; Li, F.; Feng, S.; Shu, G.; Wang, L.; Gao, P.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, C.; Wang, S.; et al. RNA-binding Protein YBX1 Promotes Brown Adipogenesis and Thermogenesis via PINK1/PRKN-mediated Mitophagy. FASEB J. 2022, 36, e22219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yao, Y.; Han, J.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Tang, Z.; Gao, F. Longitudinal Epitranscriptome Profiling Reveals the Crucial Role of N6-Methyladenosine Methylation in Porcine Prenatal Skeletal Muscle Development. J. Genet. Genom. 2020, 47, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Q.; Chen, Y.; Bai, D.-P.; Mai, L.; Fan, Q.-M.; Shi, Y.-Z.; Chen, C.; Li, A. Differential Expression of MSTN, IGF2BP1, and FABP2 across Different Embryonic Ages and Sexes in White Muscovy Ducks. Gene 2022, 829, 146479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Yang, C.; Xu, S.; Ji, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, H.; Deng, Z.; Liang, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhi, E.; et al. RNA-Binding Protein IGF2BP1 Is Required for Spermatogenesis in an Age-Dependent Manner. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Sun, K.; Yu, S.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, J.; Hu, H.; Dai, L.; Cui, M.; Jiang, C.; et al. A Mettl16/M6A/Mybl2b/Igf2bp1 Axis Ensures Cell Cycle Progression of Embryonic Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cells. EMBO J. 2024, 43, 1990–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regué, L.; Minichiello, L.; Avruch, J.; Dai, N. Liver-Specific Deletion of IGF2 MRNA Binding Protein-2/IMP2 Reduces Hepatic Fatty Acid Oxidation and Increases Hepatic Triglyceride Accumulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 11944–11951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Wu, S.; Zhang, L.; Li, W.; Xiang, D.; Kasim, V. The Biological Roles and Molecular Mechanisms of M6A Reader IGF2BP1 in the Hallmarks of Cancer. Genes Dis. 2025, 12, 101567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.; Qin, Y.; Ren, W. Insulin-like Growth Factor 2 MRNA-Binding Protein 1 (IGF2BP1) in Hematological Diseases. Mol. Med. 2024, 30, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, H.; Guo, X.; Zhu, Z.; Cai, H.; Kong, X. Insulin-like Growth Factor 2 MRNA-Binding Protein 1 (IGF2BP1) in Cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 11, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicchetto, A.C.; Jacobson, E.C.; Sunshine, H.; Wilde, B.R.; Krall, A.S.; Jarrett, K.E.; Sedgeman, L.; Turner, M.; Plath, K.; Iruela-Arispe, M.L.; et al. ZFP36-Mediated MRNA Decay Regulates Metabolism. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makita, S.; Takatori, H.; Nakajima, H. Post-Transcriptional Regulation of Immune Responses and Inflammatory Diseases by RNA-Binding ZFP36 Family Proteins. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 711633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáenz-Narciso, B.; Bell, S.E.; Matheson, L.S.; Venigalla, R.K.C.; Turner, M. ZFP36-Family RNA-Binding Proteins in Regulatory T Cells Reinforce Immune Homeostasis. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.E.; Bradstreet, T.R.; Webber, A.M.; Kim, J.; Santeford, A.; Harris, K.M.; Murphy, M.K.; Tran, J.; Abdalla, N.M.; Schwarzkopf, E.A.; et al. The ZFP36 Family of RNA Binding Proteins Regulates Homeostatic and Autoreactive T Cell Responses. Sci. Immunol. 2022, 7, eabo0981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén-Boixet, J.; Buzon, V.; Salvatella, X.; Méndez, R. CPEB4 Is Regulated during Cell Cycle by ERK2/Cdk1-Mediated Phosphorylation and Its Assembly into Liquid-like Droplets. Elife 2016, 5, e19298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, J.D. CPEB: A Life in Translation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2007, 32, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-S.; Kan, M.-C.; Lin, C.-L.; Richter, J.D. CPEB3 and CPEB4 in Neurons: Analysis of RNA-Binding Specificity and Translational Control of AMPA Receptor GluR2 MRNA. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 4865–4876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Huang, X.; Ruan, X.; Shang, X.; Zhang, M.; Liu, L.; Wang, P.; An, P.; Lin, Y.; Yang, J.; et al. Cpeb4-Mediated Dclk2 Promotes Neuronal Pyroptosis Induced by Chronic Cerebral Ischemia through Phosphorylation of Ehf. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2024, 44, 1655–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arasaki, Y.; Hayata, T. The RNA-binding Protein Cpeb4 Regulates Splicing of the Id2 Gene in Osteoclast Differentiation. J. Cell. Physiol. 2024, 239, e31197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ollà, I.; Pardiñas, A.F.; Parras, A.; Hernández, I.H.; Santos-Galindo, M.; Picó, S.; Callado, L.F.; Elorza, A.; Rodríguez-López, C.; Fernández-Miranda, G.; et al. Pathogenic Mis-Splicing of CPEB4 in Schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 2023, 94, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parras, A.; Anta, H.; Santos-Galindo, M.; Swarup, V.; Elorza, A.; Nieto-González, J.L.; Picó, S.; Hernández, I.H.; Díaz-Hernández, J.I.; Belloc, E.; et al. Autism-like Phenotype and Risk Gene MRNA Deadenylation by CPEB4 Mis-Splicing. Nature 2018, 560, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Sun, H.; Wen, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, S.; WANG, J.-G.; Liu, X.-P. Expression of CPEB4 in Invasive Ductal Breast Carcinoma and Its Prognostic Significance. Onco Targets Ther. 2015, 8, 3499–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Zapater, E.; Pineda, D.; Martínez-Bosch, N.; Fernández-Miranda, G.; Iglesias, M.; Alameda, F.; Moreno, M.; Eliscovich, C.; Eyras, E.; Real, F.X.; et al. Key Contribution of CPEB4-Mediated Translational Control to Cancer Progression. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CHEN, Y.; TSAI, Y.-H.; TSENG, S.-H. Regulation of the Expression of Cytoplasmic Polyadenylation Element Binding Proteins for the Treatment of Cancer. Anticancer. Res. 2016, 36, 5673–5680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ishizuka, T.; Bao, H.-L.; Wada, K.; Takeda, Y.; Iida, K.; Nagasawa, K.; Yang, D.; Xu, Y. Structure-Dependent Binding of HnRNPA1 to Telomere RNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 7533–7539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, S.; Roy, I.; Appadurai, R.; Srivastava, A. The Ribonucleoprotein HnRNPA1 Mediates Binding to RNA and DNA Telomeric G-Quadruplexes through an RGG-Rich Region. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 108491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.-H.; Chen, C.-C.; Hsiao, Y.-C.; Lin, Y.-H.; Pi, W.-C.; Huang, P.-R.; Wang, T.-C.V.; Chen, C.-Y. Heterogeneous Nuclear Ribonucleoproteins A1 and A2 Function in Telomerase-Dependent Maintenance of Telomeres. Cancers 2019, 11, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Xu, D.; Feng, H.; Ren, Z.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Yu, J.; Cang, S. HnRNPA1 Promotes the Metastasis and Proliferation of Gastric Cancer Cells through WISP2-Guided Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway. Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J.P.; Thibault, P.A.; Salapa, H.E.; Levin, M.C. A Comprehensive Analysis of the Role of HnRNP A1 Function and Dysfunction in the Pathogenesis of Neurodegenerative Disease. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 659610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salapa, H.E.; Thibault, P.A.; Libner, C.D.; Ding, Y.; Clarke, J.-P.W.E.; Denomy, C.; Hutchinson, C.; Abidullah, H.M.; Austin Hammond, S.; Pastushok, L.; et al. HnRNP A1 Dysfunction Alters RNA Splicing and Drives Neurodegeneration in Multiple Sclerosis (MS). Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Tang, P.L.F.; Wang, J.; Bao, S.; Shieh, J.T.; Leung, A.W.L.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, F.; Wong, S.Y.Y.; Hui, A.L.C.; et al. Mutations in Hnrnpa1 Cause Congenital Heart Defects. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e98555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Yang, W.; Chen, Z.; Chen, J.; Meng, Y.; Feng, B.; Sun, L.; Dou, L.; Li, J.; Cui, Q.; et al. Long Noncoding RNA LncSHGL Recruits HnRNPA1 to Suppress Hepatic Gluconeogenesis and Lipogenesis. Diabetes 2018, 67, 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, W.; Zhu, W.F.; Zhu, Y.; Tang, S.; Zheng, F.; Yin, X.; Lin, X.; Li, H. LncRNAH19 Improves Insulin Resistance in Skeletal Muscle by Regulating Heterogeneous Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein A1. Cell Commun. Signal. 2020, 18, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Shen, L.; Ouyang, Z.; Li, M.; Deng, G.; Yang, C.; Zheng, W.; Kong, L.; Wu, X.; Wu, X.; et al. Loss of HnRNP A1 in Murine Skeletal Muscle Exacerbates High-Fat Diet-Induced Onset of Insulin Resistance and Hepatic Steatosis. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 12, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, J.H.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, W.; Kim, S.G. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Hepatic Stellate Cells Promotes Liver Fibrosis via PERK-Mediated Degradation of HNRNPA1 and Up-Regulation of SMAD2. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 181–193.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shi, S. The Roles of hnRNP A2/B1 in RNA Biology and Disease. WIREs RNA 2021, 12, e1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; Flavell, R.A.; Li, H.-B. RNA M6A Modification and Its Function in Diseases. Front. Med. 2018, 12, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wu, D.; Deng, N.; Xu, F.; Luo, S.; Fan, X.; Guo, H.; Chen, J.; Li, W.; Si, X. HNRNPA2B1: A Novel Target in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1497938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, X.; Du, R.; Guo, S.; Feng, X.; Yu, T.; OuYang, Q.; Chen, Q.; Fan, X.; Wang, X.; Guo, C.; et al. PGE2 -EP3 Axis Promotes Brown Adipose Tissue Formation through Stabilization of WTAP RNA Methyltransferase. EMBO J. 2022, 41, e110439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Cui, P.; Sun, Q.; Du, Z.; Chen, Z.; Li, Z.; Liu, C.; Cao, Y.; Yang, Z.; Liu, R.; et al. PSPC1 Regulates CHK1 Phosphorylation through Phase Separation and Participates in Mouse Oocyte Maturation. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2021, 53, 1527–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Bashkenova, N.; Hong, Y.; Lyu, C.; Guallar, D.; Hu, Z.; Malik, V.; Li, D.; Wang, H.; Shen, X.; et al. A TET1-PSPC1-Neat1 Molecular Axis Modulates PRC2 Functions in Controlling Stem Cell Bivalency. Cell Rep. 2022, 39, 110928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-L.; Chen, X.-H.; Xu, B.; Chen, M.; Zhu, S.; Meng, N.; Wang, J.-Z.; Zhu, H.; Chen, D.; Liu, J.-B.; et al. K235 Acetylation Couples with PSPC1 to Regulate the M6A Demethylation Activity of ALKBH5 and Tumorigenesis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, T.; Cheng, X.; Zhu, Q.; Han, Z.; Zhu, K.; Tan, J.; Liu, M.; Chen, W.; Chen, X.; Chen, X.; et al. LncRNA LOC105369504 Inhibits Tumor Proliferation and Metastasis in Colorectal Cancer by Regulating PSPC1. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeiwa, T.; Ikeda, K.; Suzuki, T.; Sato, W.; Iino, K.; Mitobe, Y.; Kawabata, H.; Horie, K.; Inoue, S. PSPC1 Is a Potential Prognostic Marker for Hormone-Dependent Breast Cancer Patients and Modulates RNA Processing of ESR1 and SCFD2. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemster, A.-L.; Weingart, A.; Bottner, J.; Perner, S.; Sailer, V.; Offermann, A.; Kirfel, J. Elevated PSPC1 and KDM5C Expression Indicates Poor Prognosis in Prostate Cancer. Hum. Pathol. 2023, 138, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Navickas, A.; Asgharian, H.; Culbertson, B.; Fish, L.; Garcia, K.; Olegario, J.P.; Dermit, M.; Dodel, M.; Hänisch, B.; et al. RBMS1 Suppresses Colon Cancer Metastasis through Targeted Stabilization of Its MRNA Regulon. Cancer Discov. 2020, 10, 1410–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, H.; Jiao, T.; Feng, M.; Na, F.; Sun, M.; Zhao, M.; Xue, L.; et al. RBMS1 Promotes Gastric Cancer Metastasis through Autocrine IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 Signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Guo, J.; Feng, J.; Li, T.; Xu, B.; Li, W.; Yang, N.; Ji, W.; Zhuang, S.; Geng, Y.; et al. Deficiency of the RNA-Binding Protein RBMS1 Improves Myocardial Fibrosis and Heart Failure. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 47, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, L.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Tan, M.; Liu, C. Circular RNA Rbms1 Inhibited the Development of Myocardial Ischemia Reperfusion Injury by Regulating MiR-92a/BCL2L11 Signaling Pathway. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 3082–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, B.; Le Borgne, M.; Chartier, N.T.; Billaud, M.; Almeida, R. MEX-3 Proteins: Recent Insights on Novel Post-Transcriptional Regulators. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2013, 38, 477–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, Y.; Bishop, C.E.; Lu, B. Mex3c Regulates Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF1) Expression and Promotes Postnatal Growth. Mol. Biol. Cell 2012, 23, 1404–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haemmerle, M.W.; Batmanov, K.; Sen, S.; Varney, M.J.; Utecht, A.T.; Good, A.L.; Scota, A.V.; Tersey, S.A.; Ghanem, L.R.; Philpott, C.C.; et al. RNA Binding Proteins PCBP1 and PCBP2 Regulate Pancreatic β Cell Translation. Mol. Metab. 2025, 98, 102175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimura, K.; Kano, F.; Murata, M. Identification of PCBP2, a Facilitator of IRES-Mediated Translation, as a Novel Constituent of Stress Granules and Processing Bodies. RNA 2008, 14, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Xin, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Bao, W.; Lin, X.; Yin, B.; Zhao, J.; Yuan, J.; Qiang, B.; Peng, X. RNA-Binding Protein PCBP2 Modulates Glioma Growth by Regulating FHL3. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 2103–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haemmerle, M.W.; Scota, A.V.; Khosravifar, M.; Varney, M.J.; Sen, S.; Good, A.L.; Yang, X.; Wells, K.L.; Sussel, L.; Rozo, A.V.; et al. RNA-Binding Protein PCBP2 Regulates Pancreatic β Cell Function and Adaptation to Glucose. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, e172436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; He, L.; Xu, Z.; Luo, X.; Ji, L.; Lin, C.; Giuliano, A.E.; Cui, X.; Deng, Z.; Wu, J.; et al. PCBP2 Mediates Olaparib Resistance in Breast Cancer by Inhibiting M6A Methylation to Stabilize PARP1 MRNA. Cancer Res. 2025, 85, 3949–3965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palusa, S.; Ndaluka, C.; Bowen, R.A.; Wilusz, C.J.; Wilusz, J. The 3′ Untranslated Region of the Rabies Virus Glycoprotein MRNA Specifically Interacts with Cellular PCBP2 Protein and Promotes Transcript Stability. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y. PCBP2 Promotes NRG4 MRNA Stability to Diminish Angiotensin II-Induced Hypertrophy, NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation, and Oxidative Stress of AC16 Cardiomyocytes. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2025, 83, 4989–5001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Pan, X.; Tang, J.; Liu, Z.; Luo, M.; Wen, Y. The Binding of PCBP2 to IGF2 MRNA Restores Mitochondrial Function in Granulosa Cells to Ameliorate Ovarian Function in Premature Ovarian Insufficiency Mice. Cell. Signal. 2025, 136, 112103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najib, S.; Martín-Romero, C.; González-Yanes, C.; Sánchez-Margalet, V. Role of Sam68 as an Adaptor Protein in Signal Transduction. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2005, 62, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukong, K.E.; Richard, S. Sam68, the KH Domain-Containing SuperSTAR. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Rev. Cancer 2003, 1653, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, J.N.-M.; Sánchez-Vidaña, D.I.; Anoopkumar-Dukie, S.; Li, Y.; Benson Wui-Man, L. RNA-Binding Protein Signaling in Adult Neurogenesis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 982549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowd, V.; Kass, J.D.; Sarkar, N.; Ramakrishnan, P. Role of Sam68 as an Adaptor Protein in Inflammatory Signaling. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielli, P.; Busà, R.; Paronetto, M.P.; Sette, C. The RNA-Binding Protein Sam68 Is a Multifunctional Player in Human Cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2011, 18, R91–R102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisone, P.; Pradella, D.; Di Matteo, A.; Belloni, E.; Ghigna, C.; Paronetto, M.P. SAM68: Signal Transduction and RNA Metabolism in Human Cancer. Biomed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 528954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungfleisch, J.; Gebauer, F. RNA-Binding Proteins as Therapeutic Targets in Cancer. RNA Biol. 2025, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Feng, D.; Zhou, J.; Liu, L.; Li, X.; Yuan, Z.; Wu, J.; Yao, H. Targeting RNA Binding Proteins with Small-Molecule Inhibitors: Advances, Challenges, and Therapeutic Opportunities. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, F.F.; Preet, R.; Aguado, A.; Vishwakarma, V.; Stevens, L.E.; Vyas, A.; Padhye, S.; Xu, L.; Weir, S.J.; Anant, S.; et al. Impact of HuR Inhibition by the Small Molecule MS-444 on Colorectal Cancer Cell Tumorigenesis. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 74043–74058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Wu, K.; Li, Y.; Sun, R.; Li, X. Human Antigen R: A Potential Therapeutic Target for Liver Diseases. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 155, 104684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Hjelmeland, A.B.; Nabors, L.B.; King, P.H. Anti-Cancer Effects of the HuR Inhibitor, MS-444, in Malignant Glioma Cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2019, 20, 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, S.; Appadurai, M.I.; Maurya, S.K.; Nallasamy, P.; Marimuthu, S.; Shah, A.; Atri, P.; Ramakanth, C.V.; Lele, S.M.; Seshacharyulu, P.; et al. MUC16 Promotes Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Lung Metastasis by Modulating RNA-Binding Protein ELAVL1/HUR. Breast Cancer Res. 2023, 25, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegri, L.; Baldan, F.; Roy, S.; Aubé, J.; Russo, D.; Filetti, S.; Damante, G. The HuR CMLD-2 Inhibitor Exhibits Antitumor Effects via MAD2 Downregulation in Thyroid Cancer Cells. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dev, A.J.R.; Malhotra, L.; Kashyap, A.; Umar, S.M.; Rathee, M.; Samanta, S.; Kharkwal, R.; Sengupta, D.; Prasad, C.P. Biophysical and Molecular Characterization of HuR Inhibitors, CMLD-2 and Dihydrotanshinone I (DHTS), in Triple Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 320, 145848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhong, C.; He, L.; Zhang, Y.; Armaly, A.M.; Aubé, J.; Welch, D.R.; Xu, L.; Wu, X. Functional Inhibition of the RNA-binding Protein HuR Sensitizes Triple-negative Breast Cancer to Chemotherapy. Mol. Oncol. 2023, 17, 1962–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Chen, P.; Polireddy, K.; Wu, X.; Wang, T.; Ramesh, R.; Dixon, D.A.; Xu, L.; Aubé, J.; Chen, Q. An RNA-Binding Protein, Hu-Antigen R, in Pancreatic Cancer Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition, Metastasis, and Cancer Stem Cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2020, 19, 2267–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arneson-Wissink, P.C.; Pelz, K.; Worley, B.; Mendez, H.; Pham, P.; Diba, P.; Levasseur, P.R.; McCarthy, G.; Chitsazan, A.; Brody, J.R.; et al. The RNA-Binding Protein HuR Impairs Adipose Tissue Anabolism in Pancreatic Cancer Cachexia 2024. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minuesa, G.; Albanese, S.K.; Xie, W.; Kazansky, Y.; Worroll, D.; Chow, A.; Schurer, A.; Park, S.-M.; Rotsides, C.Z.; Taggart, J.; et al. Small-Molecule Targeting of MUSASHI RNA-Binding Activity in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brücksken, K.A.; Sicking, M.; Korsching, E.; Suárez-Arriaga, M.C.; Espinoza-Sánchez, N.A.; Marzi, A.; Fuentes-Pananá, E.M.; Kemper, B.; Götte, M.; Eich, H.T.; et al. Musashi Inhibitor Ro 08–2750 Attenuates Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cell Proliferation and Migration and Acts as a Novel Chemo- and Radiosensitizer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2025, 186, 118002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, K.; Yu, G.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, T.; Ling, Q.; Man, W.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, W. HNRNPA1 Gene Is Highly Expressed in Colorectal Cancer: Its Prognostic Implications and Potential as a Therapeutic Target. J. South. Med. Univ. 2024, 44, 1685–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, S.; Bley, N.; Busch, B.; Glaß, M.; Lederer, M.; Misiak, C.; Fuchs, T.; Wedler, A.; Haase, J.; Bertoldo, J.B.; et al. The Oncofetal RNA-Binding Protein IGF2BP1 Is a Druggable, Post-Transcriptional Super-Enhancer of E2F-Driven Gene Expression in Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 8576–8590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, A.; Hassan Dalhat, M.; Jahan, S.; Choudhry, H.; Imran Khan, M. BTYNB, an Inhibitor of RNA Binding Protein IGF2BP1 Reduces Proliferation and Induces Differentiation of Leukemic Cancer Cells. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 30, 103569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Li, Z.; Lin, W.; Xie, R.; Huang, H. RNA Epigenetics in Cancer: Current Knowledge and Therapeutic Implications. MedComm 2025, 6, e70322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S. RNA Binding Protein as an Emerging Therapeutic Target for Cancer Prevention and Treatment. J. Cancer Prev. 2017, 22, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Pu, W.; Chen, S.; Peng, Y. Therapeutic Targeting of RNA-Binding Protein by RNA-PROTAC. Mol. Ther. 2021, 29, 1940–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| RBP Name | Binding Domain | Target RNAs | Functional Significance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QKI | KHx1 | Ucp1, Pgcα | Negative regulator of thermogenesis | [66] |

| HuR | RRMx3 | Atgl, Insig1 | Negative regulator of adipogenesis, thermogenesis, and lipid homeostasis | [67,68,69,70,71,72] |

| YBX-1 | CSD | Pink1 Ulk1 Jmjd1c | Promotes thermogenesis and adipogenesis | [73,74,75,76] |

| YBX-2 | CSD | Cidec and Plin1 | Regulator of adipogenesis and lipid storage | [77,78] |

| CELF1 | RRMx3 | C/Ebpβ, Dio2 | Inhibits adipogenesis, activates thermogenesis, and promotes energy expenditure | [79,80] |

| IGF2BP1 | RRMx2; KHx4 | Not known | Regulates adipogenesis and adipose metabolism | [81,82,83] |

| ZFP36 | Tandem CCCH zinc-finger domains | Fgf21, Rnf128 | Lipid metabolism and whole-body insulin function | [84,85] |

| CPEB4 | RRMx2 | Not known | Pro-adipogenic factor, and its inhibition protects against obesity and metabolic disease | [86,87] |

| HnRNPA1 | RRMx2 | Ccl2 | Regulates metabolic homeostasis by reducing adipose tissue inflammation | [88] |

| HnRNPA2B1 | RRMx2 | Tnfα, Il-6, and Il-1β | Cold induced thermogenesis, inflammation | [89,90,91] |

| PSPC1 | RRMx2 | Ddx3x | Adipogenesis and lipid storage | [92] |

| RBMS1 | RRMx2 | Not known | Regulates adipogenic differentiation | [93,94,95] |

| MEX3C | KHx2; Znf_RINGx1 | Not known | Whole-body energy metabolism | [96,97] |

| PCBP2 | KHx3 | Not known | Adipogenesis | [98] |

| SAM68 | KHx1 | Not known | Adipogenesis, thermogenesis, and insulin signaling | [99,100,101,102,103] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dairi, G.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Mahri, S.A.; Al-Regaiey, K.; Malik, S.S.; Mohammad, S. RNA-Binding Proteins in Adipose Biology: From Mechanistic Understanding to Therapeutic Opportunities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 756. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020756

Dairi G, Ibrahim MA, Mahri SA, Al-Regaiey K, Malik SS, Mohammad S. RNA-Binding Proteins in Adipose Biology: From Mechanistic Understanding to Therapeutic Opportunities. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):756. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020756

Chicago/Turabian StyleDairi, Ghida, Maria Al Ibrahim, Saeed Al Mahri, Khalid Al-Regaiey, Shuja Shafi Malik, and Sameer Mohammad. 2026. "RNA-Binding Proteins in Adipose Biology: From Mechanistic Understanding to Therapeutic Opportunities" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 756. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020756

APA StyleDairi, G., Ibrahim, M. A., Mahri, S. A., Al-Regaiey, K., Malik, S. S., & Mohammad, S. (2026). RNA-Binding Proteins in Adipose Biology: From Mechanistic Understanding to Therapeutic Opportunities. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 756. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020756