Metal Pollution in the Air and Its Effects on Vulnerable Populations: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Metals in Air Pollution, Sources, and Mechanisms of Toxicity

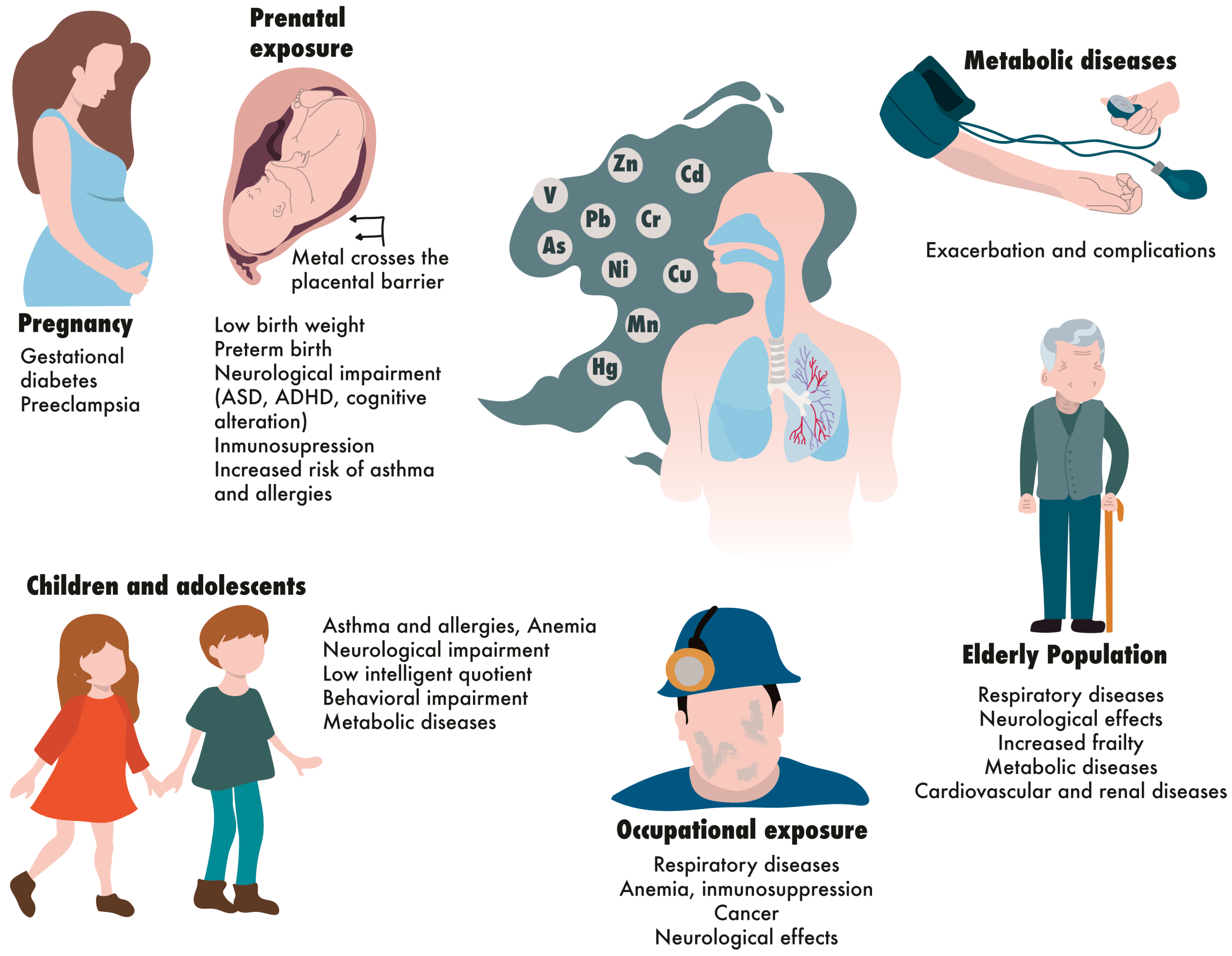

3. Vulnerability Due to Age-Related Susceptibility

3.1. Prenatally Exposed Individuals

3.2. Children and Adolescents

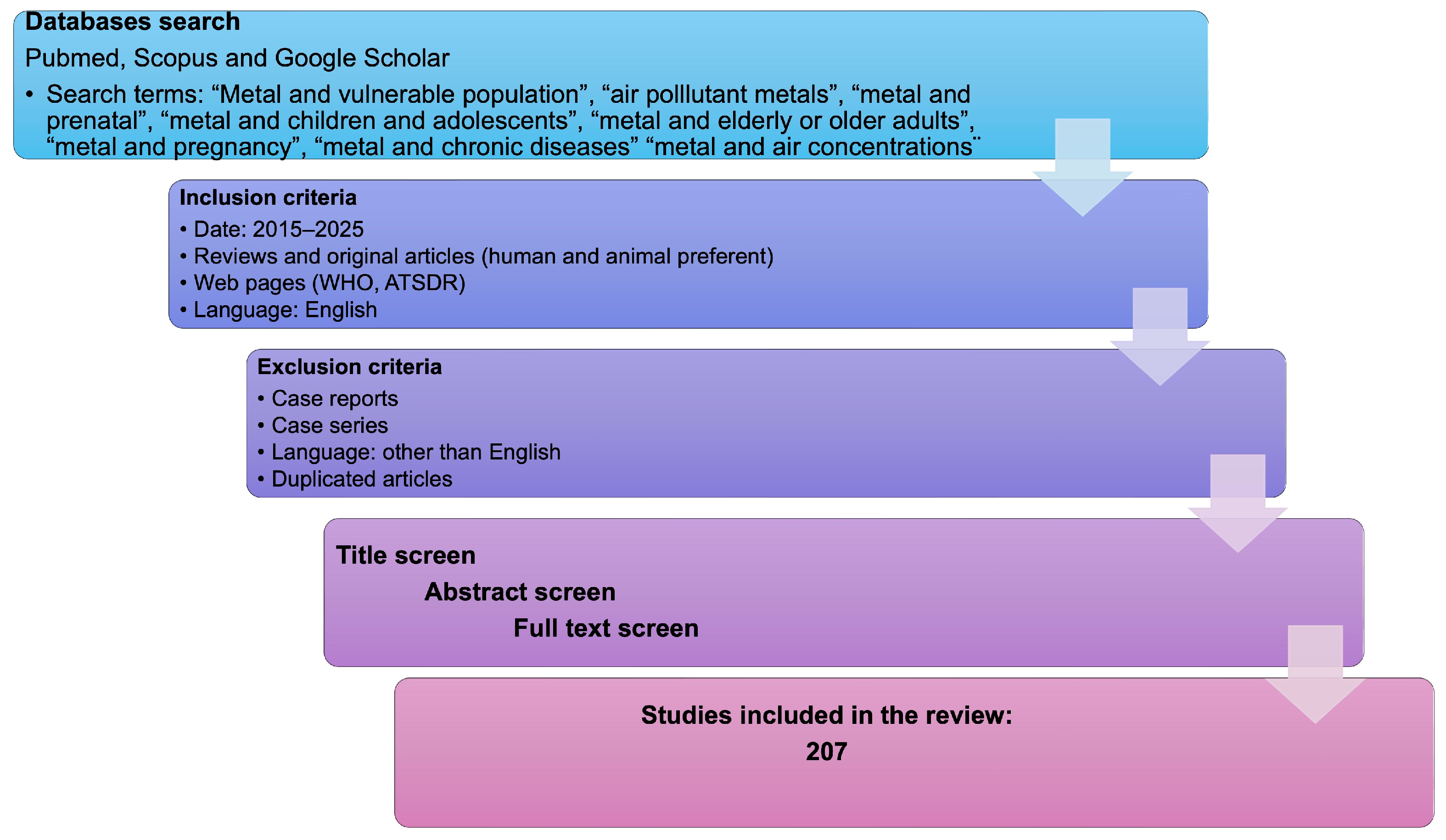

3.3. Older Adults

4. Vulnerability Due to Pregnancy

5. Vulnerability Due to Chronic and Metabolic Diseases

6. Vulnerability Due to High and Cumulative Exposure to Metals

7. Materials and Methods

8. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADHD | Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder |

| ADLs | Activities of daily living |

| ALAD | Delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydrogenase |

| ARDS | Acute respiratory distress syndrome |

| ASD | Autism spectrum disorder |

| BLL | Blood lead level |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| CTR1 | Copper transporters |

| CYP | Cytochrome P450 |

| eGFR | Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| GST | Glutathione S-transferase |

| HIF-1 | Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha |

| IADLs | Instrumental activities of daily living |

| IARC | International Agency for Research on Cancer |

| IQ | Intelligence quotient |

| JAK/STAT | Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription |

| LAPs | Lipid accumulation products |

| MAPKs | Mitogen-activated protein kinases |

| MDI | Mental development index |

| MMSE | Mini-Mental State Examination |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor-kappa B |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PLGF | Placental growth factor |

| PM | Particulate matter |

| T2D | Type 2 diabetes |

| TIM-3 | T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-containing protein |

| VAI | Visceral adiposity index |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- World Health Organization. Vulnerability and Vulnerable Populations. Available online: https://wkc.who.int/our-work/health-emergencies/knowledge-hub/community-disaster-risk-management/vulnerability-and-vulnerable-populations (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Chae, D.H.; Snipes, S.A.; Chung, K.W.; Martz, C.D.; LaVeist, T.A. Vulnerability and Resilience: Use and Misuse of These Terms in the Public Health Discourse. Am. J. Public Health 2021, 111, 1736–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorokowska, A.; Pytlinska, A.; Frackowiak, T.; Sorokows, P.; Oleszkiewicz, A.; Stefanczyk, M.M.; Rokosz, M. Perceived vulnerability to disease in pregnancy and parenthood and its impact on newborn health. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dunea, D.; Iordache, S.; Pohoata, A. A Review of Airborne Particulate Matter Effects on Young Children’s Respiratory Symptoms and Diseases. Atmosphere 2018, 9, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formichi, C.; Caprio, S.; Nigi, L.; Dotta, F. The impact of environmental pollution on metabolic health and the risk of non-communicable chronic metabolic diseases in humans. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2025, 35, 103975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Li, A.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, Q.; Zhao, M.; Xu, J.; Li, R.; Li, Y.; Li, K.; Ge, X.; et al. Association of long-term air pollution exposure with the risk of prediabetes and diabetes: Systematic perspective from inflammatory mechanisms, glucose homeostasis pathway to preventive strategies. Environ. Res. 2023, 216, 114472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lay, A.M.; Saunders, R.; Lifshen, M.; Breslin, C.; LaMontagne, A.; Tompa, E.; Smith, P. Individual, occupational, and workplace correlates of occupational health and safety vulnerability in a sample of Canadian workers. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2016, 59, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Rojas, C.; Jones, B.C. Sex Differences in Neurotoxicogenetics. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virolainen, S.J.; VonHandorf, A.; Viel, K.; Weirauch, M.T.; Kottyan, L.C. Gene-environment interactions and their impact on human health. Genes Immun 2023, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, S. Genetic factors influencing individual susceptibility to toxic agents. Res. Rev. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Stud. 2024, 12, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Heavy metals: Toxicity and human health effects. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 153–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Villalva, A.; Marcela, R.L.; Nelly, L.V.; Patricia, B.N.; Guadalupe, M.R.; Brenda, C.T.; Maria Eugenia, C.V.; Martha, U.C.; Isabel, G.P.; Fortoul, T.I. Lead systemic toxicity: A persistent problem for health. Toxicology 2025, 515, 154163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Xu, X.; Zheng, X.; Reponen, T.; Chen, A.; Huo, X. Heavy metals in PM2.5 and in blood, and children’s respiratory symptoms and asthma from an e-waste recycling area. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 210, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiordelisi, A.; Piscitelli, P.; Trimarco, B.; Coscioni, E.; Iaccarino, G.; Sorriento, D. The mechanisms of air pollution and particulate matter in cardiovascular diseases. Heart Fail. Rev. 2017, 22, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al osman, M.; Yang, F.; Massey, I.Y. Exposure routes and health effects of heavy metals on children. Biometals 2019, 32, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jomova, K.; Makova, M.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Rhodes, C.J.; Valko, M. Essential metals in health and disease. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2022, 367, 110173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohiagu, F.O.; Chikezie, P.C.; Ahaneku, C.C.; Chikezie, C.M. Human exposure to heavy metals: Toxicity mechanisms and health implications. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 6, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balali-Mood, M.; Naseri, K.; Tahergorabi, Z.; Khazdair, M.R.; Sadeghi, M. Toxic mechanisms of five heavy metals: Mercury, lead, chromium, cadmium, and arsenic. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 643972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Caminero, A.; Howe, P.D.; Hughes, M.; Kenyon, E.; Lewis, D.R.; Moore, M.; Ng, J.; Aitio, A.; Becking, G. Arsenic and Arsenic Compounds. World Health Organization, 2001. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/42366 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Baker, B.A.; Cassano, V.A.; Murray, C. ACOEM Task Force on Arsenic Exposure. Arsenic Exposure, Assessment, Toxicity, Diagnosis, and Management: Guidance for Occupational and Environmental Physicians. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 60, e634–e639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATSDR. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Addendum to Toxicological Profile for Arsenic. 2016. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/TSP/ToxProfiles/ToxProfiles.aspx?id=22&tid=3 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Palma-Lara, I.; Martínez-Castillo, M.; Quintana-Pérez, J.C.; Arellano-Mendoza, M.G.; Tamay-Cach, F.; Valenzuela-Limón, O.L.; García-Montalvo, E.A.; Hernández-Zavala, A. Arsenic exposure: A public health problem leading to several cancers. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 110, 104539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genchi, G.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Lauria, G.; Carocci, A.; Catalano, A. The effects of cadmium toxicity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhani, I.; Sahab, S.; Srivastava, V.; Singh, R.P. Impact of cadmium pollution on food safety and human health. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2021, 27, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Han, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhu, Z.; Tong, Z.; Shao, X.; Peng, J.; Hamid, Y.; Yang, X.; Deng, Y.; et al. Heavy metal content and health risk assessment of atmospheric particles in China: A meta-analysis. Sci Total Environ. 2023, 867, 161556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordberg, M.; Nordberg, G.F. Metallothionein and CadmiumToxicology—Historical Review and Commentary. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charkiewicz, A.E.; Omeljaniuk, W.J.; Nowak, K.; Garley, M.; Nikliński, J. Cadmium Toxicity and Health Effects-A Brief Summary. Molecules 2023, 28, 6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saedi, S.; Watson, S.E.; Young, J.L.; Tan, Y.; Wintergerst, K.A.; Cai, L. Does maternal low-dose cadmium exposure increase the risk of offspring to develop metabolic syndrome and/or type 2 diabetes? Life Sci. 2023, 315, 121385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrifar, Y.; Pirami, H.; Farhang Dehghan, S. Occupational Exposure to Cadmium and Its Compounds: A Review on Health Effects and Monitoring Techniques. JOHE 2025, 14, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Hu, J.; Zhang, B.; Li, Y.; Wise, J.P.; Bassig, B.A.; Zhou, A.; Savitz, D.A.; Xiong, C.; Zhao, J.; et al. A case-control study of maternal exposure to chromium and infant low birth weight in China. Chemosphere 2016, 144, 1484–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kapoor, D.; Wang, J.; Shahzad, B.; Kumar, V.; Bali, A.S.; Jasrotia, S.; Zheng, B.; Yuan, H.; Yan, D. Chromium bioaccumulation and its impacts on plants: An overview. Plants 2020, 9, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, J.J.; Bansal, N.; Chirwa, E.M. Chromium in environment, its toxic effect from chromite-mining and ferrochrome industries, and its possible bioremediation. Expos. Health 2018, 12, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.S.; Marini, J.; Solo-Gabriele, H.M.; Robey, N.M.; Townsend, T.G. Arsenic, copper, and chromium from treated wood products in the US disposal sector. Waste Manag. 2019, 87, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ma, H.; Chen, X.; Zhu, C.; Li, X. Effect of incineration temperature on chromium speciation in real chromium-rich tannery sludge under air atmosphere. Environ. Res. 2020, 183, 109159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumolo, M.; Ancona, V.; De Paola, D.; Losacco, D.; Campanale, C.; Massarelli, C.; Uricchio, V.F. Chromium pollution in European water, sources, health risk, and remediation strategies: An overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.; Dey, S.; Ram, D.K.; Reis, A.P. Hexavalent chromium pollution and its sustainable management through bioremediation. Geomicrobiol. J. 2023, 41, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, C.C.; Gómez, M.E.B.; Zavala, A.H. Hexavalent chromium: Regulation and health effects. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2021, 65, 126729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Hu, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, B.; Liu, W.; Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Hu, C.; Chen, X.; Xia, W.; et al. Exposure to chromium during pregnancy and longitudinally assessed fetal growth: Findings from a prospective cohort. Environ. Int. 2018, 121, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavesi, T.; Moreira, J.C. Mechanisms and individuality in chromium toxicity in humans. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2020, 40, 1183–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuana, R.A.; Okieimen, F.E. Heavy Metals in Contaminated Soils: A Review of Sources, Chemistry, Risks and Best Available Strategies for Remediation. ISRN Ecol Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2011, 402647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.A.; Alhadlaq, H.A.; Ahmad, J.; Al-Khedhairy, A.A.; Musarrat, J.; Ahamed, M. Copper Oxide Nanoparticles Induced Mitochondria Mediated Apoptosis in Human Hepatocarcinoma Cells. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oorts, K. Copper. In Heavy Metals in Soils. Environmental Pollution; Alloway, B., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibber, S.; Shanker, R. Can CuO Nanoparticles Lead to Epigenetic Regulation of Antioxidant Enzyme System? J. Appl. Toxicol. 2017, 37, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukai, T.; Ushio-Fukai, M.; Kaplan, J.H. Copper Transporters and Copper Chaperones: Roles in Cardiovascular Physiology and Disease. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2018, 315, C186–C201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, X.; Zhou, L.; Zeng, Q.; Zhu, H.; Luo, J. High Serum Copper as a Risk Factor of All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality among US Adults, NHANES 2011–2014. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1340968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gembillo, G.; Labbozzetta, V.; Giuffrida, A.E.; Peritore, L.; Calabrese, V.; Spinella, C.; Stancanelli, M.R.; Spallino, E.; Visconti, L.; Santoro, D. Potential Role of Copper in Diabetes and Diabetic Kidney Disease. Metabolites 2023, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, M.C. Copper Homeostasis in Mammals, with Emphasis on Secretion and Excretion: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsvetkov, P.; Coy, S.; Petrova, B.; Dreishpoon, M.; Verma, A.; Abdusamad, M.; Rossen, J.; Joesch-Cohen, L.; Humeidi, R.; Spangler, R.D.; et al. Copper Induces Cell Death by Targeting Lipoylated TCA Cycle Proteins. Science 2022, 375, 1254–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO (World Health Organization). Lead Poisoning. September 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lead-poisoning-and-health (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Mielke, H.W.; Gonzales, C.R.; Powell, E.T.; Egendorf, S.P. Lead in Air, Soil, and Blood: Pb Poisoning in a Changing World. Int Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andjelkovic, M.; Djordjevic, A.B.; Antonijevic, E.; Antonijevic, B.; Stanic, M.; Kotur-Stevuljevic, J.; Spasojevic-Kalimanovska, V.; Jovanovic, M.; Boricic, N.; Wallace, D.; et al. Toxic Effect of Acute Cadmium and Lead Exposure in Rat Blood, Liver, and Kidney. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATSDR Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Toxicological Profile for Lead. 2020. Available online: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/ToxProfiles/tp13.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Chen, P.; Bornhorst, J.; Aschner, M. Manganese metabolism in humans. Front. Biosci. 2018, 23, 1655–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aschner, M.; Erikson, K. Manganese. Adv. Nutr. 2017, 8, 520–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundseth, K.; Pacyna, J.M.; Pacyna, E.G.; Pirrone, N.; Thorne, R.J. Global Sources and Pathways of Mercury in the Context of Human Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.-S.; Osman, A.I.; Hosny, M.; Elgarahy, A.M.; Eltaweil, A.S.; Rooney, D.W.; Chen, Z.; Rahim, N.S.; Sekar, M.; Gopinath, S.C.B.; et al. The Toxicity of Mercury and Its Chemical Compounds: Molecular Mechanisms and Environmental and Human Health Implications: A Comprehensive Review. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 5100–5126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulaikhah, S.T.; Wahyuwibowo, J.; Pratama, A.A. Mercury and its effect on human health: A review of the literature. Int. J. Public Health Sci. 2020, 9, 103−114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.K.; Reddy, R.C.; Bagoji, I.B.; Das, S.; Bagali, S.; Mullur, L.; Khodnapur, J.P.; Biradar, M.S. Primary concept of nickel toxicity—An overview. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2018, 30, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, U.; Mujica Roncery, L.; Raabe, D.; Souza Filho, I.R. Sustainable nickel enabled by hydrogen-based reduction. Nature 2025, 641, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åkerlund, E.; Islam, M.S.; McCarrick, S.; Alfaro-Moreno, E.; Karlsson, H.L. Inflammation and (secondary) genotoxicity of Ni and NiO nanoparticles. Nanotoxicology 2019, 13, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Yang, Q.; Ouyang, Y.; Lou, Y.; Cui, H.; Deng, H.; Zhu, Y.; Geng, Y.; Ouyang, P.; Chen, L.; et al. Nickel induces blood-testis barrier damage through ROS-mediated p38 MAPK pathways in mice. Redox Biol. 2023, 67, 102886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, M.; Feng, L.; Tian, M.; Mu, X.; Bu, S.; Liu, J.; Xie, J.; Xie, Y.; Hou, L.; Li, G. Huaxian formula alleviates nickel oxide nanoparticle-induced pulmonary fibrosis via PI3K/AKT signaling. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.T.; Li, C.T.; Tang, S.C.; Hsin, I.L.; Lai, Y.C.; Hsiao, Y.P.; Ko, J.L. Nickel chloride regulates ANGPTL4 via the HIF-1α-mediated TET1 expression in lung cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2021, 352, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, S.; Du, Q.; Liu, Y.; Qin, C.; Wu, B. The Protective Effects of Methionine on Nickel-Induced Oxidative Stress via NF-κB Pathway in the Kidneys of Mice. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2025, 203, 3234–3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imtiaz, M.; Rizwan, M.S.; Xiong, S.; Li, H.; Ashraf, M.; Shahzad, S.M.; Shahzad, M.; Rizwan, M.; Tu, S. Vanadium, recent advancements and research prospects: A review. Environ. Int. 2015, 80, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlesinger, W.H.; Klein, E.M.; Vengosh, A. Global biogeochemical cycle of vanadium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 26, E11092–E11100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Lemus, M.; López-Valdez, N.; Bizarro-Nevares, P.; González-Villalva, A.; Ustarroz-Cano, M.; Zepeda-Rodríguez, A.; Pasos-Nájera, F.; García-Peláez, I.; Rivera-Fernández, N.; Fortoul, T.I. Toxic Effects of Inhaled Vanadium Attached to Particulate Matter: A Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, S.; Díaz, A.; Sánchez-Lara, E.; Sanchez-Gaytan, B.L.; Perez-Aguilar, J.M.; González-Vergara, E. Vanadium in Biological Action: Chemical, Pharmacological Aspects, and Metabolic Implications in Diabetes Mellitus. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2019, 188, 68–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehder, D. Perspectives for vanadium in health issues. Futur. Med. Chem. 2016, 8, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatola, O.I.; Olaolorun, F.A.; Olopade, F.E.; Olopade, J.O. Trends in vanadium neurotoxicity. Brain Res. Bull. 2019, 145, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirkhanloo, H.; Faghihi-Zarandi, A.; Mobarake, M.D. Thiol modified bimodal mesoporous silica nanoparticles for removal and determination toxic vanadium from air and human biological samples in petrochemical workers. NanoImpact 2021, 23, 100339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ścibior, A.; Pietrzyk, Ł.; Plewa, Z.; Skiba, A. Vanadium: Risks and possible benefits in the light of a comprehensive overview of its pharmacotoxicological mechanisms and multi-applications with a summary of further research trends. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2020, 61, 126508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agnew, U.M.; Slesinger, T.L. Zinc Toxicity. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Orlando, FL, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554548/ (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Lundin, K.K.; Qadeer, Y.K.; Wang, Z.; Virani, S.; Leischik, R.; Lavie, C.J.; Strauss, M.; Krittanawong, C. Contaminant Metals and Cardiovascular Health. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2023, 10, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoofs, H.; Schmit, J.; Rink, L. Zinc Toxicity: Understanding the Limits. Molecules 2024, 29, 3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, K.; Fatima, F.; Waheed, I.; Akash, M.S.H. Prevalence of exposure of heavy metals and their impact on health consequences. J. Cell. Biochem. 2018, 119, 157–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, W.; Zhou, Q.; Lai, Z.; Pu, Y.; Yin, L. The Role of Autophagy in Copper-Induced Apoptosis and Developmental Neurotoxicity in SH-SY5Y Cells. Toxics 2025, 13, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hajjar, L.; Hindieh, J.; Andraos, R.; El-Sabban, M.; Daher, J. Myeloperoxidase-Oxidized LDL Activates Human Aortic Endothelial Cells through the LOX-1 Scavenger Receptor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaetke, L.M.; Chow-Johnson, H.S.; Chow, C.K. Copper: Toxicological relevance and mechanisms. Arch. Toxicol. 2014, 88, 1929–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baj, J.; Flieger, W.; Barbachowska, A.; Kowalska, B.; Flieger, M.; Forma, A.; Teresiński, G.; Portincasa, P.; Buszewicz, G.; Radzikowska-Büchner, E.; et al. Consequences of Disturbing Manganese Homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, K.A. Is Prenatal Lead Exposure a Concern in Infancy? What Is the Evidence? Adv. Neonatal Care 2015, 15, 416–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eaves, L.A.; Lodge, E.K.; Rohin, W.R.; Roell, K.R.; Manuck, T.A.; Fry, R.C. Prenatal metal(loid) exposure and preterm birth: A systematic review of the epidemiologic evidence. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2025, 35, 696–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, M.; Shibata, E.; Morokuma, S.; Tanaka, R.; Senju, A.; Araki, S.; Sanefuji, M.; Koriyama, C.; Yamamoto, M.; Ishihara, Y.; et al. The association between whole blood concentrations of heavy metals in pregnant women and premature births: The Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS). Environ. Res. 2018, 166, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inadera, H.; Takamori, A.; Matsumura, K.; Tsuchida, A.; Cui, Z.-G.; Hamazaki, K.; Tanaka, T.; Ito, M.; Kigawa, M.; Origasa, H.; et al. Association of blood cadmium levels in pregnant women with infant birth size and small for gestational age infants: The Japan Environment and Children’s study. Environ. Res. 2020, 191, 110007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsanya, M.K.; Willkens, M.; Peck, R.N.; Kapiga, S.H.; Nyanza, E.C. Exposure to toxic chemical elements (Pb, Cd, and Hg) and its association with sustained high blood pressure among secondary school attending adolescents in Northwestern Tanzania. Environ. Res. 2025, 278, 121738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO (World Health Organization). Mercury. Octubre 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mercury-and-health# (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Dack, K.; Fell, M.; Taylor, C.M.; Havdahl, A.; Lewis, S.J. Prenatal Mercury Exposure and Neurodevelopment up to the Age of 5 Years: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X.; Heinrich, J.; Zhang, J.; Schramm, K.-W.; Huang, Q.; Tian, M.; Eqani, S.A.M.A.S.; Shen, H. A nested case-control study indicating heavy metal residues in meconium associate with maternal gestational diabetes mellitus risk. Environ. Health 2015, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, B.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ge, W.; Yang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, P.; Si, J.; et al. Personal exposure to PM2.5 constituents associated with gestational blood pressure and endothelial dysfunction. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 250, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Liu, W.; Zhang, B.; Shen, X.; Hu, C.; Chen, X.; Jin, S.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, H.; Cao, Z.; et al. Maternal Heavy Metal Exposure, Thyroid Hormones, and Birth Outcomes: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 104, 5043–5052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Xia, W.; Pan, X.; Zheng, T.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, A.; Buka, S.L.; Bassig, B.A.; Liu, W.; Wu, C.; et al. Association of adverse birth outcomes with prenatal exposure to vanadium: A population-based cohort study. Lancet Planet. Health 2017, 1, e230–e241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Peng, Y.; Zheng, T.; Zhang, B.; Liu, W.; Wu, C.; Jiang, M.; Braun, J.M.; Liu, S.; Buka, S.L.; et al. Effects of trimester-specific exposure to vanadium on ultrasound measures of fetal growth and birth size: A longitudinal prospective prenatal cohort study. Lancet Planet. Health 2018, 2, e427–e437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordas, K.; Ardoino, G.; Coffman, D.L.; Queirolo, E.I.; Ciccariello, D.; Mañay, N.; Ettinger, A.S. Patterns of Exposure to Multiple Metals and Associations with Neurodevelopment of Preschool Children from Montevideo, Uruguay. J. Environ. Public Health 2015, 493471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, A.P.; Claus, H.B.; Wright, R.O. Perinatal and Childhood Exposure to Cadmium, Manganese, and Metal Mixtures and Effects on Cognition and Behavior: A Review of Recent Literature. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2015, 2, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Igusa, T.; Wang, G.; Buckley, J.P.; Hong, X.; Bind, E.; Steffens, A.; Mukherjee, J.; Haltmeier, D.; Ji, Y.; et al. In-utero co-exposure to toxic metals and micronutrients on childhood risk of overweight or obesity: New insight on micronutrients counteracting toxic metals. Int. J. Obes. 2022, 46, 1435–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.H.; Jung, C.R.; Lin, C.Y.; Chang, Y.C.; Hsieh, C.Y.; Hsu, P.C.; Chuang, B.R.; Hwang, B.F. Prenatal and postnatal exposure to heavy metals in PM2.5 and autism spectrum disorder. Environ. Res. 2023, 237, 116874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Sharkey, K.; Mitra, S.; Chow, T.; Paik, S.A.; Thompson, L.; Su, J.; Cockburn, M.; Ritz, B. Prenatal exposure to criteria air pollution and traffic-related air toxics and risk of autism spectrum disorder: A population-based cohort study of California births (1990–2018). Environ. Int. 2025, 201, 109562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, H.; Ritz, B.; Warren, J.L.; Pollitt, K.G.; Liew, Z. Ambient toxic air contaminants in the maternal residential area during pregnancy and cerebral palsy in the offspring. Environ. Health Perspect. 2025, 133, 17008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skogheim, T.S.; Weyde, K.V.F.; Engel, S.M.; Aase, H.; Surén, P.; Øie, M.G.; Biele, G.; Reichborn Kjennerud, T.; Caspersen, I.H.; Hornig, M.; et al. Metal and Essential Element Concentrations during Pregnancy and Associations with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children. Environ. Int. 2021, 152, 106468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Mahai, G.; Zheng, D.; Yan, M.; Huang, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Xia, W.; Xu, S. Effects of prenatal vanadium exposure on neurodevelopment in early childhood and identification of critical window. Environ. Res. 2025, 276, 121506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farias, P.M.; Marcelino, G.; Santana, L.F.; de Almeida, E.B.; Guimarães, R.C.A.; Pott, A.; Hiane, P.A.; Freitas, K.C. Minerals in Pregnancy and Their Impact on Child Growth and Development. Molecules 2020, 25, 5630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Chen, H.; Zeng, Q.; Xu, S.; Xia, W.; Li, Y. Prenatal and postnatal exposure to vanadium and the immune function of children. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2021, 67, 126787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokopciuk, N.; Taminskiene, V.; Vaideliene, L.; Juskiene, I.; Svist, V.; Valiulyte, I.; Valskys, V.; Valskiene, R.; Valiulis, A.; Aukstikalnis, T.; et al. The incidence of upper respiratory infections in children is related to the concentration of vanadium in indoor dust aggregates. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1339755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charkiewicz, A.E.; Omeljaniuk, W.J.; Garley, M.; Nikliński, J. Mercury Exposure and Health Effects: What Do We Really Know? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, K.A.; Larcombe, A.N.; Sly, P.D.; Zosky, G.R. In utero exposure to low dose arsenic via drinking water impairs early life lung mechanics in mice. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.Y.; Jung, C.R.; Lin, C.Y.; Hwang, B.F. Combined exposure to heavy metals in PM2.5 and pediatric asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 147, 2171–2180.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Q.; Zhang, W.X.; Zheng, T.Z.; Zhou, B.; Li, J.X.; Zhang, B.; Xia, W.; Li, Y.; Xu, S.Q. Prenatal and postnatal cadmium exposure and cellular immune responses among pre-school children. Environ. Int. 2020, 134, 105282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesce, G.; Sesé, L.; Calciano, B.; Travert, B.; Dessimond, C.N.; Maesano, G.; Ferrante, G.; Huel, J.; Prud’homme, M.; Guinot, M.; et al. Isabella Annesi-Maesano Foetal exposure to heavy metals and risk of atopic diseases in early childhood. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2021, 32, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeester, L.; Fry, R.C. Long-Term Health Effects and Underlying Biological Mechanisms of Developmental Exposure to Arsenic. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2018, 5, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, K.F.; Ungewitter, E.K.; Crespo-Mejias, Y.; Liu, C.; Nicol, B.; Kissling, G.E.; Yao, H.H. Effects of in Utero Exposure to Arsenic during the Second Half of Gestation on Reproductive End Points and Metabolic Parameters in Female CD-1 Mice. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Guo, X.; Wu, B.; Yu, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, M. Arsenic induces diabetic effects through beta-cell dysfunction and increased gluconeogenesis in mice. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 6894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pánico, P.; Velasco, M.; Salazar, A.M.; Picones, A.; Ortiz-Huidobro, R.I.; Guerrero-Palomo, G.; Salgado-Bernabé, M.E.; Ostrosky-Wegman, P.; Hiriart, M. Is Arsenic Exposure a Risk Factor for Metabolic Syndrome? A Review of the Potential Mechanisms. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 878280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig-Pijuan, T.; Souza, L.R.Q.; Pedrosa, C.d.S.G.; Higa, L.M.; Monteiro, F.L.; Tanuri, A.; Valverde, R.H.F.; Einicker-Lamas, M.; Rehen, S.K. Copper Regulation Disturbance Linked to Oxidative Stress and Cell Death during Zika Virus Infection in Human Astrocytes. J. Cell. Biochem. 2022, 123, 1997–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udom, G.J.; Iyaye, D.; Oritsemuelebi, B.; Nwanaforo, E.; Bede-Ojimadu, O.; Abdulai, P.M.; Frazzoli, C.; Orisakwe, O.E. Public health concerns of multifaceted exposures to metal and metalloid mixtures: A systematic review. Environ. Monit Assess. 2025, 197, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patriarca, M.; Menditto, A.; Rossi, B.; Lyon, T.D.B.; Fell, G.S. Environmental exposure to metals of newborns, infants and young children. Microchem. J. 2000, 67, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neal, S.L.; Zheng, W. Manganese Toxicity Upon Overexposure: A Decade in Review. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2015, 2, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Signes-Pastor, A.J.; Martinez-Camblor, P.; Baker, E.; Madan, J.; Guill, M.F.; Karagas, M.R. Prenatal exposure to arsenic and lung function in children from the New Hampshire Birth Cohort Study. Environ. Int. 2021, 155, 106673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, T.R.; Powers, M.; Perzanowski, M.; George, C.M.; Graziano, J.H.; Navas-Acien, A. A Meta-analysis of Arsenic Exposure and Lung Function: Is There Evidence of Restrictive or Obstructive Lung Disease? Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2018, 5, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Akhtar, E.; Roy, A.; von Ehrenstein, O.S.; Vahter, M.; Wagatsuma, Y.; Raqib, R. Arsenic exposure alters lung function and airway inflammation in children: A cohort study in rural Bangladesh. Environ. Int. 2017, 101, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recio-Vega, R.; Gonzalez-Cortes, T.; Olivas-Calderon, E.; Lantz, R.C.; Gandolfi, A.J.; Gonzalez-De Alba, C. In utero and early childhood exposure to arsenic decreases lung function in children. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2015, 35, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, X.; Feng, M.; Zhang, J.; Yu, H.; Chi, H.; Li, X.; Yan, L.; Yu, P.; Ye, T.; et al. Associations between blood nickel and lung function in young Chinese: An observational study combining epidemiology and metabolomics. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 284, 116963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatem, G.; Faria, A.M.; Pinto, M.B.; Teixeira, J.P.; Salamova, A.; Costa, C.; Madureira, J. Association between exposure to airborne endocrine disrupting chemicals and asthma in children or adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 369, 125830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isufi, D.; Jensen, M.B.; Kursawe Larsen, C.; Alinaghi, F.; Schwensen, J.F.B.; Johansen, J.D. Allergens Responsible for contact allergy in children from 2010 to 2024: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Contact Dermat. 2025, 92, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, N.C.; Huang, H.Y.; Wang, S.L.; Tseng, Y.L.; Chang-Chien, J.; Tsai, H.J.; Yao, T.C. Association of exposure to environmental vanadium and manganese with lung function among young children: A population-based study. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2023, 264, 115430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disalvo, L.; Varea, A.; Matamoros, N.; Sala, M.; Fasano, M.V.; González, H.F. Blood Lead Levels and Their Association with Iron Deficiency and Anemia in Children. Biol Trace Elem Res 2025, 203, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parithathvi, A.; Choudhari, N.; Dsouza, H.S. Prenatal and early life lead exposure induced neurotoxicity. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2024, 43, 9603271241285523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.X.; Hobson, K.; Benedetti, C.; Kennedy, S. Water-soluble vitamins and trace elements in children with chronic kidney disease stage 5d. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2024, 39, 1405–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, R.; Jiang, Y.; Li, W.; Ding, W.; Feng, L. Effects of Prenatal Arsenic, Cadmium, and Manganese Exposure on Neurodevelopment in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina 2025, 61, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zheng, X.; Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Yang, L. Environmental pollutant exposure and adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes: An umbrella review and evidence grading of meta-analyses. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 491, 137832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes-Filho, J.A.; Carvalho, C.F.; Rodrigues, J.L.G.; Araújo, C.F.S.; Dos Santos, N.R.; Lima, C.S.; Bandeira, M.J.; Marques, B.L.S.; Anjos, A.L.S.; Bah, H.A.F.; et al. Environmental Co-Exposure to Lead and Manganese and Intellectual Deficit in School-Aged Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Shen, L.; Khan, N.U.; Zhang, X.; Chen, L.; Zhao, H.; Luo, P. Trace elements in children with autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analysis based on case-control studies. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2021, 67, 126782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lin, J.; Zhao, X.; Yao, F.; Feng, C.; He, Z.; Cao, X.; Gao, Y.; Khan, N.U.; Chen, M.; et al. Trace Element Changes in the Plasma of Autism Spectrum Disorder Children and the Positive Correlation Between Chromium and Vanadium. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2022, 200, 4924–4935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustin, K.; Tofail, F.; Vahter, M.; Kippler, M. Cadmium exposure and cognitive abilities and behavior at 10 years of age: A prospective cohort study. Environ. Int. 2018, 113, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flannery, B.M.; Schaefer, H.R.; Middleton, K.B. A scoping review of infant and children health effects associated with cadmium exposure. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 131, 105155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pujol, J.; Fenoll, R.; Macià, D.; Martínez-Vilavella, G.; Álvarez-Pedrerol, M.; Rivas, I.; Forns, J.; Deus, J.; Blanco-Hinojo, L.; Querol, X.; et al. Airborne Copper Exposure in School Environments Associated with Poorer Motor Performance and Altered Basal Ganglia. Brain Behav. 2016, 6, e00467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masanova, V.; Uhnakova, I.; Wimmerova, S.; Trnovec, T.; Sovcikova, E.; Patayova, H.; Murinova, L.P. As, Cd, Hg, and Pb biological concentrations and anthropometry in Slovak adolescents. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2025, 203, 4052–4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yekeen, T.A.; Liu, J.; Zhuang, B.; Li, W.; Huo, X. Chromium exposure among children from an electronic waste recycling town of China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 1778–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, W.; Liu, W.; Liu, G. The relationships between serum copper levels and overweight/total obesity and central obesity in children and adolescents aged 6-18 years. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2020, 61, 126557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leff, T.; Stemmer, P.; Tyrrell, J.; Jog, R. Diabetes and Exposure to Environmental Lead (Pb). Toxics 2018, 6, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.W.; Wang, C.W.; Wu, D.W.; Lee, W.H.; Chen, Y.C.; Liu, Y.H.; Li, C.H.; Tsai, C.C.; Lin, W.Y.; Chen, S.C.; et al. Significant association between blood lead (Pb) level and haemoglobin A1c in non-diabetic population. Diabetes Metab. 2021, 47, 101233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Lima, E.; Ortega-Romero, M.; Aztatzi-Aguilar, O.G.; Rubio-Gutiérrez, J.C.; Narváez-Morales, J.; Esparza-García, M.; Méndez-Hernández, P.; Medeiros, M.; Barbier, O.C. Vanadium exposure and kidney markers in a pediatric population: A cross-sectional study. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2025, 40, 1689–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.E.; Pereira, A.; Binder, A.M.; Amarasiriwardena, C.; Shepherd, J.A.; Corvalan, C.; Michels, K.B. Time-specific impact of trace metals on breast density of adolescent girls in Santiago, Chile. Int. J. Cancer 2024, 155, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filler, G.; Kobrzynski, M.; Sidhu, H.K.; Belostotsky, V.; Huang, S.S.; McIntyre, C.; Yang, L. A cross-sectional study measuring vanadium and chromium levels in paediatric patients with CKD. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e014821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, A.P.; Mazzella, M.J.; Malin, A.J.; Hair, G.M.; Busgang, S.A.; Saland, J.M.; Curtin, P. Combined exposure to lead, cadmium, mercury, and arsenic and kidney health in adolescents age 12–19 in NHANES 2009–2014. Environ. Int. 2019, 131, 104993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-López, E.; Tamayo-Ortiz, M.; Ariza, A.C.; Ortiz-Panozo, E.; Deierlein, A.L.; Pantic, I.; Tolentino, M.C.; Estrada-Gutiérrez, G.; Parra-Hernández, S.; Espejel-Núñez, A.; et al. Early-Life Dietary Cadmium Exposure and Kidney Function in 9-Year-Old Children from the PROGRESS Cohort. Toxics 2020, 8, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, G.J.S. Therapeutic Potential of Copper Chelation with Triethylenetetramine in Managing Diabetes Mellitus and Alzheimer’s Disease. Drugs 2011, 71, 1281–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, X.; Zhu, L.; Chen, H. Association between blood heavy metal levels and COPD risk: A cross-sectional study based on NHANES data. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1494336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Q.; Weng, X.; Liu, K.; Liu, S.; Chen, J.; Guo, X.; Jing, C. The Relationship between Metal Exposure and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in the General US Population: NHANES 2015-2016. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Zhang, R.; Yang, A.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, R.; Luo, F.; Luo, H.; Chen, R.; Luo, B.; et al. Cross-sectional associations between multiple plasma heavy metals and lung function among elderly Chinese. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, F.; Chen, C.; Wang, J.; Luo, Y.; Li, C.; Xiong, J.; Lv, Y.; Li, J.; et al. Association of blood lead exposure with frailty and its components among the Chinese oldest old. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 242, 113959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza-Talarico, J.N.; Marcourakis, T.; Barbosa FJr Moraes Barros, S.B.; Rivelli, D.P.; Pompéia, S.; Caramelli, P.; Plusquellec, P.; Lupien, S.J.; Catucci, R.F.; Alves, A.R.; et al. Association between heavy metal exposure and poor working memory and possible mediation effect of antioxidant defenses during aging. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 575, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wise, J.P., Jr.; Young, J.L.; Cai, J.; Cai, L. Current understanding of hexavalent chromium [Cr (VI)] neurotoxicity and new perspectives. Environ. Int. 2022, 158, 106877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vielee, S.T.; Isibor, J.; Buchanan, W.J.; Roof, S.H.; Patel, M.; Meaza, I.; Williams, A.; Toyoda, J.H.; Lu, H.; Wise, S.S.; et al. Female rat behavior effects from low levels of hexavalent chromium (Cr [VI]) in drinking water evaluated with a toxic aging coin approach. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooqui, Z.; Bakulski, K.M.; Power, M.C.; Weisskopf, M.G.; Sparrow, D.; Spiro, A., 3rd; Vokonas, P.S.; Nie, L.H.; Hu, H.; Park, S.K. Associations of cumulative Pb exposure and longitudinal changes in Mini-Mental Status Exam scores, global cognition and domains of cognition: The VA Normative Aging Study. Environ. Res. 2017, 152, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rył, A.; Szylińska, A.; Bohatyrewicz, A.; Jurewicz, A.; Pilarczyk, B.; Tomza-Marciniak, A.; Rotter, I. Relationships Between Indicators of Metabolic Disorders and Selected Concentrations of Bioelements and Lead in Serum and Bone Tissue in Aging Men. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2022, 15, 3901–3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhou, J.; Huo, P.; Zhang, H.; Shen, H.; Huang, Q.; Chen, G.; Yang, L.; Zhang, D. Exposure to Multiple Metal(loid)s and Hypertension in Chinese Older Adults. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2025, 203, 2944–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, R.; Tan, A.; Shen, S.; Xiong, Y.; Zhao, L.; Lei, X. Association between blood lead levels and hyperlipidemiais: Results from the NHANES (1999–2018). Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 981749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Zhou, S.; Weng, Z.; Liang, G.; Gu, A. Association between nickel and multiple metabolic outcomes: The mediating roles of lipid metabolism and inflammation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 298, 118274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javorac, D.; Tatović, S.; Anđelković, M.; Repić, A.; Baralić, K.; Djordjevic, A.B.; Mihajlović, M.; Stevuljević, J.K.; Đukić-Ćosić, D.; Ćurčić, M.; et al. Low-lead doses induce oxidative damage in cardiac tissue: Subacute toxicity study in Wistar rats and Benchmark dose modelling. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 161, 112825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalili, C.; Kazemi, M.; Cheng, H.; Mohammadi, H.; Babaei, A.; Taheri, E.; Moradi, S. Associations between exposure to heavy metals and the risk of chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2021, 51, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, J.A.; David, L.; Lux, F.; Tillement, O. Low-level, chronic ingestion of lead and cadmium: The unspoken danger for at-risk populations. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 478, 135361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.-T.; Hu, B.; Meng, X.-L.; Sun, L.; Li, H.-B.; Xu, P.-R.; Cheng, B.-J.; Sheng, J.; Tao, F.-B.; Yang, L.-S.; et al. The associations between urinary metals and metal mixtures and kidney function in Chinese community-dwelling older adults with diabetes mellitus. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 226, 112829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Duan, S.; Wang, R.; He, P.; Zhang, Z.; Li, M.; Shen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, H.; et al. Associations between multiple urinary metals and metabolic syndrome: Exploring the mediating role of liver function in Chines community-dwelling elderly. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2024, 85, 127472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Wang, R.; He, P.; Sun, J.; Yang, H. Associations between multiple urinary metals and the risk of hypertension in community-dwelling older adults. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 76543–76554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yu, T.; Zhai, M.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, B.; Duan, C.; Cheng, H.; Li, H.; Wei, Z.; Yang, Y.; et al. Maternal cadmium exposure impairs placental angiogenesis in preeclampsia through disturbing thyroid hormone receptor signaling. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 244, 114055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.T.; Zhu, H.L.; Xu, X.F.; Xiong, Y.W.; Dai, L.M.; Zhou, G.X.; Liu, W.B.; Zhang, Y.F.; Xu, D.X.; Wang, H. Gestational cadmium exposure impairs placental angiogenesis via activating GC/GR signaling. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 224, 112632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Xia, W.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, A.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Hu, C.; Chen, X.; et al. Relation between cadmium exposure and gestational diabetes mellitus. Environ. Int. 2018, 113, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, M.H.; Baiz, N.; Huel, G.; Yazbeck, C.; Botton, J.; Heude, B.; Bornehag, C.G.; Annesi-Maesano, I. EDEN Mother-Child Cohort Study Group. Exposure to heavy metals during pregnancy related to gestational diabetes mellitus in diabetes-free mothers. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 656, 870–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y. Blood manganese level and gestational diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2023, 43, 2266646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.; Li, J.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Zhu, T. Association of Blood Manganese and Preeclampsia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2024, 202, 1843–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorena, K.; Jaskulak, M.; Michalska, M.; Mrugacz, M.; Vandenbulcke, F. Air Pollution, Oxidative Stress, and the Risk of Development of Type 1 Diabetes. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Villalva, A.; Colín-Barenque, L.; Bizarro-Nevares, P.; Rojas-Lemus, M.; Rodríguez-Lara, V.; García-Pelaez, I.; Ustarroz-Cano, M.; López-Valdez, N.; Albarrán-Alonso, J.C.; Fortoul, T.I. Pollution by metals: Is there a relationship in glycemic control? Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2016, 46, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Zhi, X.; Xu, M.; Li, B.; Zhang, Z. Gender-specific differences of interaction between cadmium exposure and obesity on prediabetes in the NHANES 2007-2012 population. Endocrine 2018, 61, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yimthiang, S.; Pouyfung, P.; Khamphaya, T.; Kuraeiad, S.; Wongrith, P.; Vesey, D.A.; Gobe, G.C.; Satarug, S. Effects of Environmental Exposure to Cadmium and Lead on the Risks of Diabetes and Kidney Dysfunction. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Gong, X.; Li, R.; Gao, W.; Hu, D.; Yi, X.; Liu, Y.; Fang, J.; Shao, J.; Ma, Y.; et al. Exposure to cadmium and lead is associated with diabetic kidney disease in diabetic patients. Environ. Health 2024, 23, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Wang, N.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xia, F.; Chen, B.; Dong, R.; Lu, Y. Blood lead, nutrient intake, and renal function among type 2 diabetic patients. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021, 28, 49063–49073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeppesen, C.; Valera, B.; Nielsen, N.O.; Bjerregaard, P.; Jørgensen, M.E. Association between whole blood mercury and glucose intolerance among adult Inuit in Greenland. Environ. Res. 2015, 143, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, M.; Papi, A.; Contoli, M.; Beghé, B.; Celli, B.R.; Wedzicha, J.A.; Fabbri, L.M. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation fundamentals: Diagnosis, treatment, prevention and disease impact. Respirology 2021, 26, 532–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouadri, A.; Cormenier, J.; Gemy, K.; Macari, L.; Charbonnier, P.; Richaud, P.; Michaud-Soret, I.; Alfaidy, N.; Benharouga, M. Copper-Associated Oxidative Stress Contributes to Cellular Inflammatory Responses in Cystic Fibrosis. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coradduzza, D.; Congiargiu, A.; Azara, E.; Mammani, I.M.A.; De Miglio, M.R.; Zinellu, A.; Carru, C.; Medici, S. Heavy metals in biological samples of cancer patients: A systematic literature review. Biometals 2024, 37, 803–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Zhou, R.; Zhao, Y.; Pan, Y.; Liang, H.; Zhang, J.; Tai, S.; Jin, L.; Teng, C. Blockage of SLC31A1-Dependent Copper Absorption Increases Pancreatic Cancer Cell Autophagy to Resist Cell Death. Cell Prolif. 2019, 52, e12568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezanifar, S.; Azimian, A.; Khadiv, E.; Naziri, S.H.; Gharari, N.; Fazlzadeh, M. Para-occupational exposure to chemical substances: A systematic review. Rev. Environ. Health 2023, 39, 737–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samarghandian, S.; Shirazi, F.M.; Saeedi, F.; Roshanravan, B.; Pourbagher-Shahri, A.M.; Khorasani, E.Y.; Farkhondeh, T.; Aaseth, J.O.; Abdollahi, M.; Mehrpour, O. A systematic review of clinical and laboratory findings of lead poisoning: Lessons from case reports. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. 2021, 429, 115681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessel, E.V.; Staal, Y.C.; Piersma, A.H.; den Braver-Sewradj, S.P.; Ezendam, J. Occupational exposure to hexavalent chromium. Part I. Hazard assessment of non-cancer health effects. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 126, 105048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, C.; Malik, R.N.; Chen, J. Human exposure to chromite mining pollution, the toxicity mechanism and health impact. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Bharagava, R.N. Toxic and genotoxic effects of hexavalent chromium in environment and its bioremediation strategies. J. Environ. Sci. Health 2016, 34, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, J.; Keller, L.; Pacheco, K. Updates in Metal Allergy: A Review of New Pathways of Sensitization, Exposure, and Treatment. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2025, 25, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szűcs-Somlyó, É.; Lehel, J.; Májlinger, K.; Lőrincz, M.; Kővágó, C. Metal-oxide inhalation induced fever—Immuntoxicological aspects of welding fumes. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2023, 175, 113722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reisgen, M.; Thomas, K.; Beilmannn, V. The Role of Cell-Derived Iinflammation in Metal Fume Fever-Blood Count Changes after Exposure with Zinc-and Copper-Containing Welding Fumes. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 56, 648. [Google Scholar]

- Farkhondeh, T.; Samarghandian, S.; Sadighara, P. Lead exposure and asthma: An overview of observational and experimental studies. Toxin Rev. 2015, 34, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, K.; Manna, P.; Dey, T.; Kalita, J.; Unni, B.G.; Ozah, D.; Baruah, P.K. Circulatory heavy metals (cadmium, lead, mercury, and chromium) inversely correlate with plasma GST activity and GSH level in COPD patients and impair NOX4/Nrf2/GCLC/GST signaling pathway in cultured monocytes. Toxicol. Vitr. 2019, 54, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, C.D.; Garcia, S.C.; Brucker, N.; Goethel, G.; Sauer, E.; Lacerda, L.M.; Oliveira, E.; Trombini, T.L.; Machado, A.B.; Pressotto, A.; et al. Occupational risk assessment of exposure to metals in chrome plating workers. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 45, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bidu, N.S.; Lemos, D.S.; Fernandes, B.J.D. Occupational exposure to arsenic and leukopenia risk: Toxicological alert. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2024, 40, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Si, H.; Jin, X.; Guo, Y.; Xia, J.; He, J.; Deng, X.; Deng, M.; Yao, W.; Hao, C. Changes in serum TIM-3 and complement C3 expression in workers due to Mn exposure. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1289838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Y.; Si, H.; Jin, X.; Guo, Y.; Xia, J.; He, J.; Deng, X.; Deng, M.; Yao, W.; Hao, C. Expression levels of key immune indicators and immune checkpoints in manganese-exposed rats. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 272, 116029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, E.; Calderón-Salinas, V.; Hérnandez-Franco, P.; Loaiza, B.; Maldonado-Vega, M.; Martínez-Baeza, E.; Mussali-Galante, P.; Ramos-Espinosa, P.; Silva-Aguilar, M.; Tovar-Sánchez, E.; et al. Workers exposed to lead at a battery recycling plant in Mexico: Blood lead levels; DNA damage and repair in blood cells (comet assay). Mutat. Res. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2025, 907, 503882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasak, T.; Dujlovic, T.; Barth, A. Manganese exposure and cognitive performance: A meta-analytical approach. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 332, 121884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjørklund, G.; Peana, M.; Dadar, M.; Chirumbolo, S.; Aaseth, J.; Martins, N. Mercury-induced autoimmunity: Drifting from micro to macro concerns on autoimmune disorders. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 213, 108352–108358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashari, A.; Kazi, T.G.; Afridi, H.I.; Baig, J.A.; Arain, M.B.; Lashari, A.A. Evaluate the Work-Related Exposure of Vanadium on Scalp Hair Samples of Outdoor and Administrative Workers of Oil Drilling Field: Related Health Risks. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2024, 202, 5366–5372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Q.; Jing, J.; He, H.; Huang, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, M.; Qi, Z.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Z.; Yan, Y.; et al. Manganese induces podocyte injury through regulating MTDH/ALKBH5/NLRP10 axis: Combined analysis at epidemiology and molecular biology levels. Environ. Int. 2024, 187, 108672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, L.; Patel, T.N. Systemic impact of heavy metals and their role in cancer development: A review. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IARC. International Agencia for Research on Cancer. Available online: https://monographs.iarc.who.int/list-of-classifications/ (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Deng, Y.; Wang, M.; Tian, T.; Lin, S.; Xu, P.; Zhou, L.; Dai, C.; Hao, Q.; Wu, Y.; Zhai, Z.; et al. The Effect of Hexavalent Chromium on the Incidence and Mortality of Human Cancers: A Meta-Analysis Based on Published Epidemiological Cohort Studies. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meaza, I.; Williams, A.R.; Wise, S.S.; Lu, H.; Wise, J.P., Sr. Carcinogenic mechanisms of hexavalent chromium: From DNA breaks to chromosome instability and neoplastic transformation. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2024, 11, 484–546, Correction in Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2025, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianicolo, E.A.L.; Mangia, C.; Cervino, M.; Bruni, A.; Portaluri, M.; Comba, P.; Pirastu, R.; Biggeri, A.; Vigotti, M.; Blettner, M. Long-term effect of arsenic exposure: Results from an occupational cohort study. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2019, 62, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morakinyo, O.M.; Mukhola, M.S.; Mokgobu, M.I. Health Risk Analysis of Elemental Components of an Industrially Emitted Respirable Particulate Matter in an Urban Area. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minessota Department of Labor and Industry. Available online: https://www.dli.mn.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/pels.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

| Metals | Molecular Targets Toxicity Mechanisms | References |

|---|---|---|

| Arsenic | Thiol binding and inhibition of thiol-rich enzymes: pyruvate dehydrogenase, 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase, and tyrosine phosphatases. Interaction with zinc finger proteins. Interaction with tubulin (mitotic arrest). Altered MAPKs, NF-κB. Uncoupled oxidative phosphorylation (altered ATP production). | [11,18,21,76] |

| Cadmium | Metallothionein binding. Increased metallothionein. Interference with zinc-dependent enzymes. Thiol binding and inhibition of thiol-rich enzymes. Mimicking the function and behavior of essential metals (Ca, Zn, Fe), disturbing their homeostasis. Activation of MAPKs, increased c-fos, c-jun, c-myc. Autophagy dysfunction. | [11,18,25] |

| Chromium | DNA damage. Genomic instability. | [18] |

| Copper | Interaction with kinases that lead to inhibition of autophagy. LDL oxidation. Altered lipid metabolism. Altered hepatic gene expression. Altered protein–metal interaction. | [77,78,79] |

| Lead | Mimicking divalent cations (calcium). Inactivation of specific enzymes of heme synthesis (ALAD and ferrochelatase). | [12,76] |

| Manganese | Activation of enzymes. Mitochondrial dysfunction. Altered homeostasis of other metals (Fe, Ca, and Zn). Dysregulation of glutamate transport. Impairment of dopaminergic function. | [80] |

| Mercury | Thiol binding Enzyme inhibition. Amine, amide, carboxyl, and sulfhydryl group binding. Glutamate regulation alteration. Calcium homeostasis impairment. Microtubule inhibition. Increased c-fos expression | [18,58] |

| Nickel | Thiol, sulfhydryl binding. Activation of MAPKs, PI3K, HIF-1, and NK-kB signaling pathways. | [61,62,64,76] |

| Vanadium | Phosphate binding and dysfunction of proteins and enzymes (ATPases and phosphatases). Activation or inhibition of MAPKs and JAK/STAT signaling pathways. | [70,71] |

| Zinc | Mimicking other metals. Competing for metallothionein with other metals (Cu deficiency). | [74,75] |

| Arsenic, cadmium, chromium, copper, lead, manganese, mercury, nickel, vanadium, and zinc | ROS production and decrease in antioxidant enzyme levels, leading to oxidative stress and inflammation. Nitrosative stress. Lipid peroxidation. DNA damage. Mitochondrial dysfunction. | [10,12,17,18,22,29,39,48,53,57,61,62,63,64,67,72] |

| Metal | Environmental | Occupational |

|---|---|---|

| Arsenic | 0.006 μg/m3 | 10 μg/m3 a,b |

| 2 μg/m3 c | ||

| Cadmium | 0.0003 μg/m3 | 10 μg/m3 a |

| 5 μg/m3 b,c | ||

| Chromium (Cr VI) | 0.012 μg/m3 | 500 μg/m3 a,b,c |

| Copper | 100 μg/m3 | Vapors 0.1 mg/m3 a,b |

| Dust 1 mg/m3 a,d | ||

| Lead | 0.5 μg/m3 | 50 μg/m3 a,b,c |

| Manganese | 5 mg/m3 | 20 μg/m3 a |

| 1 mg/m3 b | ||

| 200 μg/m3 c | ||

| Mercury | 5 ng/m3 * | 0.025 mg/m3 a |

| 0.1 mg/m3 b | ||

| 0.05 mg/m3 c | ||

| Nickel | 0.00024 μg/m3 | 0.007 mg/m3 b |

| Vanadium | 0.05 mg/m3 a,c | |

| ND | Dust 0.5 mg/m3 b | |

| Vapors 0.1 mg/m3 b | ||

| Zinc | ND | 5 mg/m3 b 2 mg/m3 a |

| Vulnerable Population | Metal | Toxic Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age-Related Susceptibility | |||

| Prenatally exposed individuals | Pb, As, V, Cd, Cr, Hg | Low birth weight Preterm birth | [49,81,82,83,84] |

| Hg | Congenital malformations | [49,87] | |

| Zn, Cd, Hg, As Cd, Pb | Immunosuppression Risk of postnatal respiratory infections Asthma and allergies | [27,102,103,105,106,107,108] | |

| Cu | Increased risk of congenital Zika (neurological damage) | [113] | |

| Cd, Pb, As, Ni, V, Mn, Cu, Hg | Neurodevelopmental impairment (ADHD, ASD, cognitive impairment) Lower MDI | [54,85,93,94,95,96,98,99,100] | |

| As | Epigenetic changes leading to metabolic diseases: glucose intolerance, diabetes, dyslipidemia, liver steatosis. Increased risk of cancer in early life | [21,109,110,111,112] | |

| Children and adolescents | Mn | Increased infant mortality | [116] |

| Pb | Seizures, coma, and death | [15] | |

| Cd | Stunted growth in male adolescents | [85] | |

| Pb, Cd, V | Osteoporosis Hypertension Increased risk of cancer | [15,52,85,142] | |

| As, Mn, Ni, Pb, V | Lung damage Asthma Reduced lung capacity Atopic dermatitis | [117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124] | |

| Pb, Zn | Anemia and neutropenia | [125,126,127] | |

| Pb, Cr, Cu | Obesity Increased risk of diabetes | [85,127,136,137,138,139,140] | |

| V, Cr, Cd, Cu | Kidney damage | [141,143,144,145,146] | |

| Cu | Liver damage | [146] | |

| Cu | Motor impairment and alteration of basal ganglia | [135] | |

| As, Pb, Cd, Mn, Hg, Cr, V | Neurodevelopmental impairment: cognitive impairment, learning disorders, memory problems, behavioral issues, attention deficit. Lower IQ scores, ADHD, ASD | [12,15,27,80,128,129,130] | |

| Older adults | Pb, Cd, Cr, Ni | Greater risk of all-cause mortality Lung damage, COPD Increased risk of frailty | [147,148,149,150] |

| Pb, Cr | Reduced working memory, MMSE, altered motor function | [151,152,153,154] | |

| Pb, Mn, Cu, Zn, V | Obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia | [155,156,157] | |

| Ni, Pb | Cardiovascular risk | [155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164] | |

| V | Kidney damage | [162] | |

| Vulnerability due to pregnancy | Cd, Pb Mn As | Insulin resistance Gestational diabetes Epigenetic changes that increase the risk of metabolic diseases | [28,88,109,110,111,167,168,169] |

| Zn | Anemia and neutropenia | [101] | |

| Cd, Pb | Placental angiogenesis and preeclampsia | [165,166] | |

| Vulnerability due to chronic and metabolic diseases | Pb, Cd, Hg, Ni | Increased risk of worsening hyperglycemia, diabetes, metabolic syndrome Diabetes and Alzheimer’s Increased risk of cardiovascular disease | [146,171,172,173] |

| Cu | Increased risk of kidney damage Myocardial injury, atherosclerosis, arrythmia, hypertension | [15,44,45,46,146] | |

| Vulnerability due to high and cumulative exposure (occupational) | Pb | Encephalopathy, coma, and death | [12,183] |

| Ni Zn | Respiratory distress syndrome Smoke fever | [58,75,188,189] | |

| Cr (VI) | Skin, oral and respiratory epithelium damage, nasal septum necrosis | [184,185] | |

| Cr, Ni | Rhinitis, bronchitis, dermatitis | [17,187] | |

| Cd, Cr, Pb, Hg, V | Asthma, COPD | [72,190,191,199] | |

| Ni, Zn | Pulmonary fibrosis | [17,189] | |

| Mn, Cr Pb | Parkinsonism Cognitive, short-term memory impairment, behavioral alterations | [12,80,197] | |

| Hg | Acrodynia (polyneuropathy) | [198] | |

| As, Pb | Anemia, leukocyte alterations Oxidative stress and DNA damage Lymphocyte activation markers | [12,192,193,194,195,196] | |

| Mn | Immunosuppression | [195] | |

| V, Ni, Mn, Pb | Kidney damage | [12,58,72,199,200] | |

| Pb, Cr, Ni Pb, Cd, Cr, Hg, As | Increased risk of cancer IARC classification 1: As, Cr (VI), Cd, Ni; 2A: Pb; 2B: V, Hg | [58,201,203,204,205] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gonzalez-Villalva, A.; Rojas-Lemus, M.; López-Valdez, N.; Cervantes-Valencia, M.E.; Guerrero-Palomo, G.; Casarrubias-Tabarez, B.; Bizarro-Nevares, P.; Morales-Ricardes, G.; García-Peláez, I.; Ustarroz-Cano, M.; et al. Metal Pollution in the Air and Its Effects on Vulnerable Populations: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 720. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020720

Gonzalez-Villalva A, Rojas-Lemus M, López-Valdez N, Cervantes-Valencia ME, Guerrero-Palomo G, Casarrubias-Tabarez B, Bizarro-Nevares P, Morales-Ricardes G, García-Peláez I, Ustarroz-Cano M, et al. Metal Pollution in the Air and Its Effects on Vulnerable Populations: A Narrative Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):720. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020720

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzalez-Villalva, Adriana, Marcela Rojas-Lemus, Nelly López-Valdez, María Eugenia Cervantes-Valencia, Gabriela Guerrero-Palomo, Brenda Casarrubias-Tabarez, Patricia Bizarro-Nevares, Guadalupe Morales-Ricardes, Isabel García-Peláez, Martha Ustarroz-Cano, and et al. 2026. "Metal Pollution in the Air and Its Effects on Vulnerable Populations: A Narrative Review" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 720. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020720

APA StyleGonzalez-Villalva, A., Rojas-Lemus, M., López-Valdez, N., Cervantes-Valencia, M. E., Guerrero-Palomo, G., Casarrubias-Tabarez, B., Bizarro-Nevares, P., Morales-Ricardes, G., García-Peláez, I., Ustarroz-Cano, M., Salgado-Hernández, J. Á., Reséndiz Ramírez, P., Villafaña Guillén, N., Cevallos, L., Teniza, M., & Fortoul, T. I. (2026). Metal Pollution in the Air and Its Effects on Vulnerable Populations: A Narrative Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 720. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020720