Dissecting the Interaction Domains of SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein and Human RNA Helicase DDX3X and Search for Potential Inhibitors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

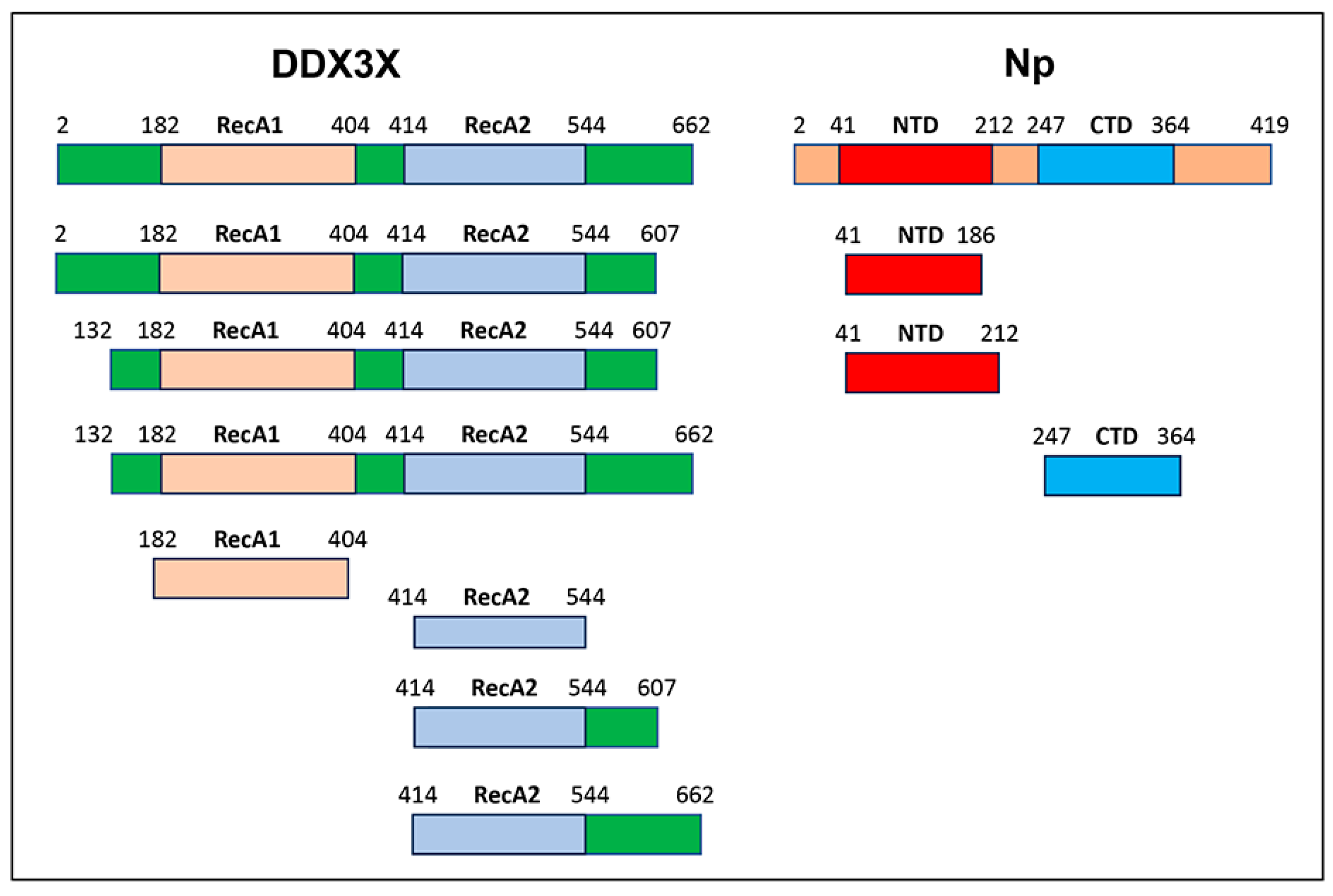

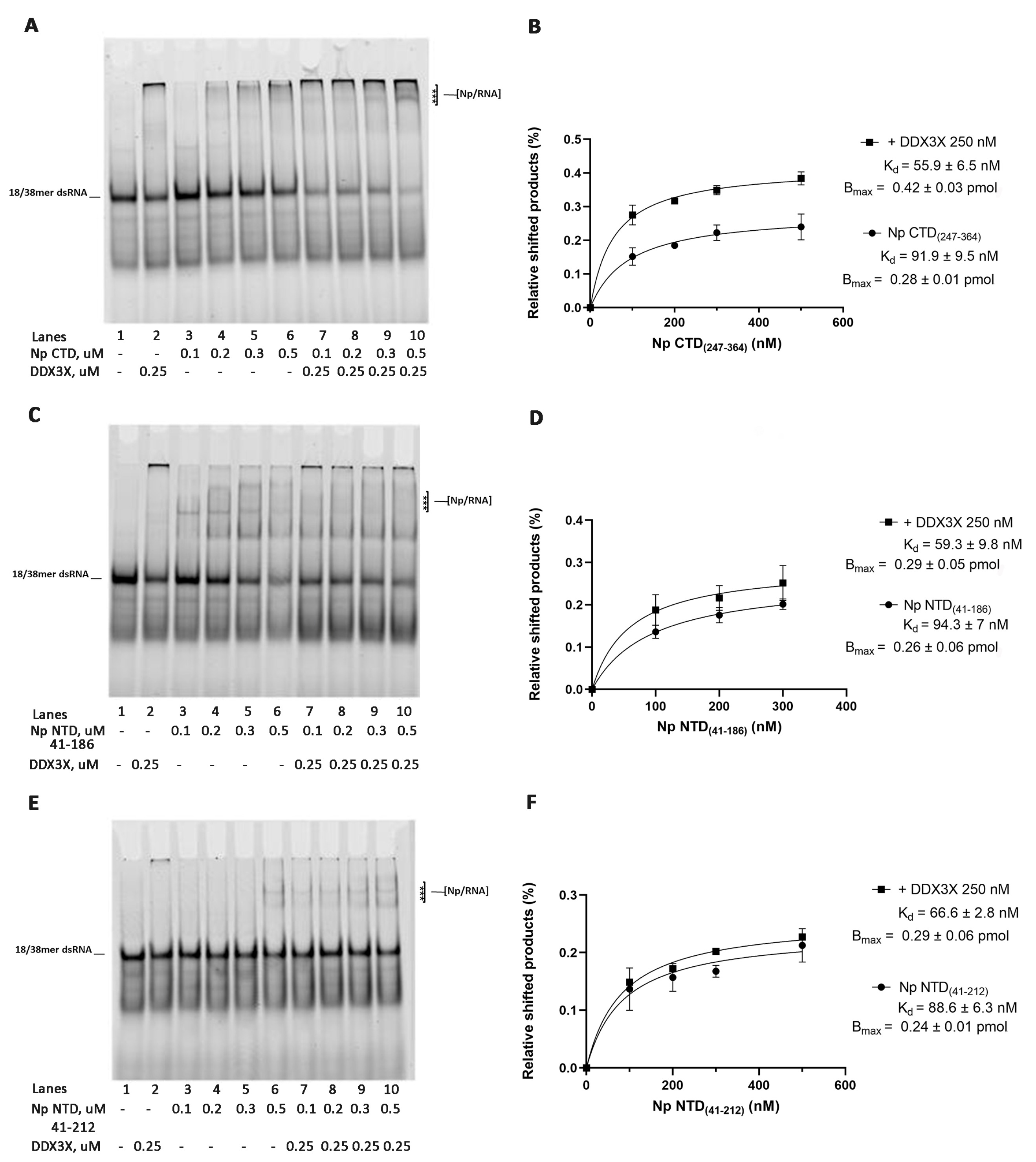

2.1. Human DDX3X Increases the Affinity of SARS-CoV-2 Np CTD and NTD Protein for dsRNA

2.2. Mapping the DDX3X Domain of Interaction with SARS-CoV 2 Np

2.3. SARS-CoV-2 Np Physically Interacts with DDX3X

2.4. AlphaFold 3 Model of DDX3X-Np Interaction

2.5. DDX3X RecA2 Domain Interact with Np

2.6. Search for Small Molecules Inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Np RNA Binding

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cloning, Expression and Purification of Recombinant Proteins

4.2. Nucleic Acid Substrates

- ssRNA 38 mer

- 5′-AUGAAGGUUUGAGUUGAGUGGAGAUAGUGGAGGGUAGU-3′

- ssRNA 18 mer FAM

- 3′-UACUUCCAAACUCAACUC-5′ FAM

4.3. EMSA

4.4. Pull-Down Assays

4.5. Western Blot

4.6. NanoBRET Assay

4.7. Computational Details

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Np | SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein |

| RNP | Ribonucleoprotein complex |

| gRNA | Genomic RNA |

| LLPS | Liquid–liquid phase separation |

| NTD | N-terminal domain |

| CTD | C-terminal domain |

| IDRs | Intrinsically disordered regions |

| LKR | Central linker region |

| dsRNA | Double stranded RNA |

| RIG-I | Retinoic acid-inducible gene-I |

| IPS-1 | Interferon-beta promoter stimulator 1 |

| HCV | Hepatitis C virus |

| EMSA | Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay |

| MBP | Maltose binding protein |

| NLuc | NanoLuc luciferase |

| TGM2 | Transglutaminase 2 |

| pTM | Predicted Template Modelling score |

| ipTM | Interface predicted TM-score |

| pLDDT | Predicted local distance difference test |

| RMSD | Root Mean Square Deviation |

References

- Mothae, S.A.; Chiliza, T.E.; Mvubu, N.E. SARS-CoV-2 host-pathogen interactome: Insights into more players during pathogenesis. Virology 2025, 610, 110607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morse, M.; Sefcikova, J.; Rouzina, I.; Beuning, P.J.; Williams, M.C. Structural domains of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein coordinate to compact long nucleic acid substrates. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Syed, A.M.; Khalid, M.M.; Nguyen, A.; Ciling, A.; Wu, D.; Yau, W.M.; Srinivasan, S.; Esposito, D.; Doudna, J.A.; et al. Assembly of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein with nucleic acid. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 6647–6661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezerra, P.R.; Almeida, F.C.L. Structural basis for the participation of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein in the template switch mechanism and genomic RNA reorganization. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 107834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laughlin, P.M.; Young, K.; Gonzalez-Gutierrez, G.; Wang, J.C.; Zlotnick, A. A narrow ratio of nucleic acid to SARS-CoV-2 N-protein enables phase separation. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 107831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, G.; Martins, M.L.; Fernandes, N.P.; Veloso, T.; Lopes, J.; Gomes, T.; Cordeiro, T.N. Dynamic ensembles of SARS-CoV-2 N-protein reveal head-to-head coiled-coil-driven oligomerization and phase separation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, gkaf502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Cao, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, J. The SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein and Its Role in Viral Structure, Biological Functions, and a Potential Target for Drug or Vaccine Mitigation. Viruses 2021, 13, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, H.; Sun, C.; Zhang, S. The SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein: Its role in the viral life cycle, structure and functions, and use as a potential target in the development of vaccines and diagnostics. Virol. J. 2023, 20, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, S.; Huang, C.; Li, B.; Li, J.; Jin, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Pan, P.; Du, W.; et al. Molecular characterization of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1415885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Y.Q.; Huang, M.; Feng, K.; Jia, Y.; Sun, X.; Ning, Y.J. A New Cellular Interactome of SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein and Its Biological Implications. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2023, 22, 100579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodola, C.; Secchi, M.; Sinigiani, V.; De Palma, A.; Rossi, R.; Perico, D.; Mauri, P.L.; Maga, G. Interaction of SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein and Human RNA Helicases DDX1 and DDX3X Modulates Their Activities on Double-Stranded RNA. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccosanti, F.; Di Rienzo, M.; Romagnoli, A.; Colavita, F.; Refolo, G.; Castilletti, C.; Agrati, C.; Brai, A.; Manetti, F.; Botta, L.; et al. Proteomic analysis identifies the RNA helicase DDX3X as a host target against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Antiviral Res. 2021, 190, 105064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, J.; Liang, H.; Su, C.; Li, P.; Chen, J.; Zhang, B. DDX3X: Structure, physiologic functions and cancer. Mol. Cancer 2021, 20, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secchi, M.; Lodola, C.; Garbelli, A.; Bione, S.; Maga, G. DEAD-Box RNA Helicases DDX3X and DDX5 as Oncogenes or Oncosuppressors: A Network Perspective. Cancers 2022, 14, 3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, J.; Choi, H.; Han, C. A Dual Role of DDX3X in dsRNA-Derived Innate Immune Signaling. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 912727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samir, P.; Kanneganti, T.D. DEAD/H-Box Helicases in Immunity, Inflammation, Cell Differentiation, and Cell Death and Disease. Cells 2022, 11, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapescu, I.; Cherry, S. DDX RNA helicases: Key players in cellular homeostasis and innate antiviral immunity. J. Virol. 2024, 98, e0004024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, S.C.; Heaton, S.M.; Audsley, M.D.; Kleifeld, O.; Borg, N.A. TRIM25 and DEAD-Box RNA Helicase DDX3X Cooperate to Regulate RIG-I-Mediated Antiviral Immunity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, V.; Maga, G. From the magic bullet to the magic target: Exploiting the diverse roles of DDX3X in viral infections and tumorigenesis. Future Med. Chem. 2019, 11, 1357–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winnard, P.T., Jr.; Vesuna, F.; Raman, V. Targeting host DEAD-box RNA helicase DDX3X for treating viral infections. Antiviral Res. 2021, 185, 104994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Mao, Q.; Weng, S.; Teng, M.; Luo, J.; Zhang, K. DDX3X and virus interactions: Functional diversity and antiviral strategies. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1630068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariumi, Y. Host Cellular RNA Helicases Regulate SARS-CoV-2 Infection. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e0000222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, S.D.; Alonso, C.; Garcia-Dorival, I. Comparative Proteomics and Interactome Analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein in Human and Bat Cell Lines. Viruses 2024, 16, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Johnson, B.A.; Meliopoulos, V.A.; Ju, X.; Zhang, P.; Hughes, M.P.; Wu, J.; Koreski, K.P.; Clary, J.E.; Chang, T.C.; et al. Interaction between host G3BP and viral nucleocapsid protein regulates SARS-CoV-2 replication and pathogenicity. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 113965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Du, N.; Lei, Y.; Dorje, S.; Qi, J.; Luo, T.; Gao, G.F.; Song, H. Structures of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid and their perspectives for drug design. EMBO J. 2020, 39, e105938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubuk, J.; Alston, J.J.; Incicco, J.J.; Singh, S.; Stuchell-Brereton, M.D.; Ward, M.D.; Zimmerman, M.I.; Vithani, N.; Griffith, D.; Wagoner, J.A.; et al. The SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein is dynamic, disordered, and phase separates with RNA. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Nguyen, A.; Wu, D.; Li, Y.; Hassan, S.A.; Chen, J.; Shroff, H.; Piszczek, G.; Schuck, P. Plasticity in structure and assembly of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein. PNAS Nexus 2022, 1, pgac049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Högbom, M.; Collins, R.; van den Berg, S.; Jenvert, R.M.; Karlberg, T.; Kotenyova, T.; Flores, A.; Karlsson Hedestam, G.B.; Schiavone, L.H. Crystal structure of conserved domains 1 and 2 of the human DEAD-box helicase DDX3X in complex with the mononucleotide AMP. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 372, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carabelli, A.M.; Peacock, T.P.; Thorne, L.G.; Harvey, W.T.; Hughes, J.; COVID-19 Genomics UK Consortium; Peacock, S.J.; Barclay, W.S.; de Silva, T.I.; Towers, G.J.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 variant biology: Immune escape, transmission and fitness. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabdano, S.O.; Ruzanova, E.A.; Vertyachikh, A.E.; Teplykh, V.A.; Emelyanova, A.B.; Rudakov, G.O.; Arakelov, S.A.; Pletyukhina, I.V.; Saveliev, N.S.; Lukovenko, A.A.; et al. N-protein vaccine is effective against COVID-19: Phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J. Infect 2024, 89, 106288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Ghosh Roy, S.; Dwivedi, R.; Tripathi, P.; Kumar, K.; Nambiar, S.M.; Pathak, R. Beyond the Pandemic Era: Recent Advances and Efficacy of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines Against Emerging Variants of Concern. Vaccines 2025, 13, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambike, S.; Cheng, C.C.; Feuerherd, M.; Velkov, S.; Baldassi, D.; Afridi, S.Q.; Porras-Gonzalez, D.; Wei, X.; Hagen, P.; Kneidinger, N.; et al. Targeting genomic SARS-CoV-2 RNA with siRNAs allows efficient inhibition of viral replication and spread. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden-Reid, E.; Moles, E.; Kelleher, A.; Ahlenstiel, C. Harnessing antiviral RNAi therapeutics for pandemic viruses: SARS-CoV-2 and HIV. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2025, 15, 2301–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Farzan, M.; Choe, H. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: Structure, viral entry and variants. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 23, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Hilgenfeld, R.; Whitley, R.; De Clercq, E. Therapeutic strategies for COVID-19: Progress and lessons learned. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2023, 22, 449–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yu, J.; Shen, A.; Lai, S.; Liu, Z.; He, T.S. The RNA-binding proteins regulate innate antiviral immune signaling by modulating pattern recognition receptors. Virol. J. 2024, 21, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di, D.; Dileepan, M.; Ahmed, S.; Liang, Y.; Ly, H. Recombinant SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein: Expression, Purification, and Its Biochemical Characterization and Utility in Serological Assay Development to Assess Immunological Responses to SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savastano, A.; Ibáñez de Opakua, A.; Rankovic, M.; Zweckstetter, M. Nucleocapsid protein of SARS-CoV-2 phase separates into RNA-rich polymerase-containing condensates. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, X.; Gao, T.; Liu, Y.; Li, E.; Wang, X.; Cao, Z.; Zhu, L.; Dong, Q.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 N Protein Antagonizes Stress Granule Assembly and IFN Production by Interacting with G3BPs to Facilitate Viral Replication. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e0041222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Chen, S.; Lu, W.; Luo, T.; Shi, R.; Li, J.; Shen, H. Liquid-liquid phase separation of DDX3X: Mechanisms, pathological implications, and therapeutic potential. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 317, 144835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eiermann, N.; Haneke, K.; Sun, Z.; Stoecklin, G.; Ruggieri, A. Dance with the Devil: Stress Granules and Signaling in Antiviral Responses. Viruses 2020, 12, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fu, X.; Bai, G.; Li, X.; Mao, J.; Yan, Y.; Hu, L. Multiple functions of stress granules in viral infection at a glance. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1138864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brai, A.; Trivisani, C.I.; Poggialini, F.; Pasqualini, C.; Vagaggini, C.; Dreassi, E. DEAD-Box Helicase DDX3X as a Host Target against Emerging Viruses: New Insights for Medicinal Chemical Approaches. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 10195–10216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riva, V.; Garbelli, A.; Casiraghi, F.; Arena, F.; Trivisani, C.I.; Gagliardi, A.; Bini, L.; Schroeder, M.; Maffia, A.; Sabbioneda, S.; et al. Novel alternative ribonucleotide excision repair pathways in human cells by DDX3X and specialized DNA polymerases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 11551–11565, Correction in Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, gkaf578. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaf578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Secchi, M.; Garbelli, A.; Riva, V.; Deidda, G.; Santonicola, C.; Formica, T.M.; Sabbioneda, S.; Crespan, E.; Maga, G. Synergistic action of human RNaseH2 and the RNA helicase-nuclease DDX3X in processing R-loops. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 11641–11658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, L.L. Release 2021-1: Maestro, Schrödinger; LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Protein | Kd (nM) | Bmax/Kd (pmol·µM−1) |

|---|---|---|

| Np CTD(247–364) | 91.9 ± 9.5 | 3.1 ± 0.5 |

| Np CTD(247–364) + DDX3X | 55.9 ± 6.5 | 7.5 ± 0.8 |

| Np NTD(41–186) | 94.3 ± 7.0 | 2.7 ± 0.3 |

| Np NTD(41–186) + DDX3X | 59.3 ± 9.8 | 4.9 ± 0.6 |

| Np NTD(41–212) | 88.6 ± 6.3 | 2.7 ± 0.5 |

| Np NTD(41–212) + DDX3X | 66.6 ± 2.8 | 4.4 ± 0.6 |

| DDX3X(2–607) + Np | 27.2 ± 3.7 | 15.1 ± 0.9 |

| DDX3X(132–607) + Np | 25.2 ± 2.5 | 17.4 ± 1.1 |

| DDX3X(132–662) + Np | 20.5 ± 3.4 | 20.5 ± 0.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lodola, C.; Pallotta, M.M.; Manetti, F.; Governa, P.; Crespan, E.; Maga, G.; Secchi, M. Dissecting the Interaction Domains of SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein and Human RNA Helicase DDX3X and Search for Potential Inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 672. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020672

Lodola C, Pallotta MM, Manetti F, Governa P, Crespan E, Maga G, Secchi M. Dissecting the Interaction Domains of SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein and Human RNA Helicase DDX3X and Search for Potential Inhibitors. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):672. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020672

Chicago/Turabian StyleLodola, Camilla, Maria Michela Pallotta, Fabrizio Manetti, Paolo Governa, Emmanuele Crespan, Giovanni Maga, and Massimiliano Secchi. 2026. "Dissecting the Interaction Domains of SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein and Human RNA Helicase DDX3X and Search for Potential Inhibitors" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 672. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020672

APA StyleLodola, C., Pallotta, M. M., Manetti, F., Governa, P., Crespan, E., Maga, G., & Secchi, M. (2026). Dissecting the Interaction Domains of SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein and Human RNA Helicase DDX3X and Search for Potential Inhibitors. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 672. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020672