From Proteome to miRNome: A Review of Multi-Omics Ocular Allergy Research Using Human Tears

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Comorbidities

3. Developments in Multi-Omics Analysis

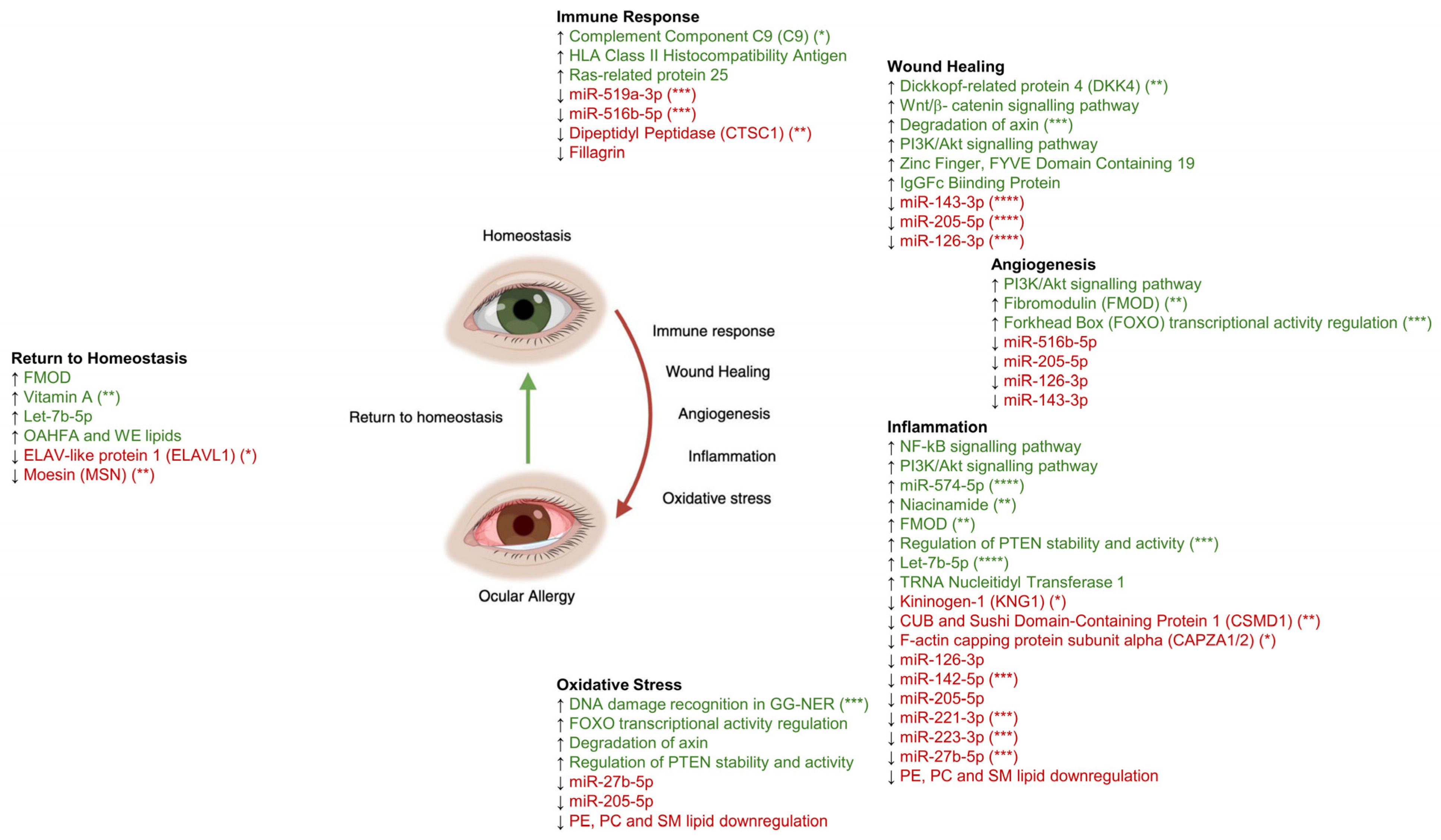

4. Systemic Multi-Omics Studies of OA-Associated Conditions

5. Immune Response

6. Wound Healing

7. Angiogenesis

8. Inflammation

9. Oxidative Stress

10. Return to Homeostasis

11. Connections to Comorbidities

12. Limitations

13. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stull, D.E.; Schaefer, M.; Crespi, S.; Sandor, D.W. Relative strength of relationships of nasal congestion and ocular symptoms with sleep, mood and productivity. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2009, 25, 1785–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, A.; Piliego, F.; Castegnaro, A.; Lazzarini, D.; La Gloria Valerio, A.; Mattana, P.; Fregona, I. Allergic conjunctivitis: A cross-sectional study. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2015, 45, 1118–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, G.; Esterich, N. Awareness of treatment: A source of bias in subjective grading of ocular complications. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0226960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Sheng, M.; Li, J.; Yan, G.; Lin, A.; Li, M.; Wang, W.; Chen, Y. Tear proteomic analysis of Sjögren syndrome patients with dry eye syndrome by two-dimensional-nano-liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, V.L.; Chen, W.; Craig, J.P.; Dogru, M.; Jones, L.; Stapleton, F.; Wolffsohn, J.S.; Sullivan, D.A. TFOS DEWS III: Executive Summary. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2026, 282, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akasaki, Y.; Inomata, T.; Sung, J.; Nakamura, M.; Kitazawa, K.; Shih, K.C.; Adachi, T.; Okumura, Y.; Fujio, K.; Nagino, K.; et al. Prevalence of Comorbidity between Dry Eye and Allergic Conjunctivitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMonnies, C.W. Mechanisms of rubbing-related corneal trauma in keratoconus. Cornea 2009, 28, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bawazeer, A.M.; Hodge, W.G.; Lorimer, B. Atopy and keratoconus: A multivariate analysis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2000, 84, 834–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weed, K.H.; MacEwen, C.J.; Giles, T.; Low, J.; McGhee, C.N.J. The Dundee University Scottish Keratoconus study: Demographics, corneal signs, associated diseases, and eye rubbing. Eye 2008, 22, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, J.V.; Leahy, C.D.; Welter, D.A.; Hearn, S.L.; Weidman, T.A.; Korb, D.R. Histopathology of the Ocular Surface After Eye Rubbing. Cornea 1997, 16, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, S.; Liu, M.; Li, H.; Fang, X.; Xie, Z.; Xiao, X.; Yang, Z.; Lin, Y.; et al. Tear IgE point-of-care testing for differentiating type I and type IV allergic conjunctivitis. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1577656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Azizoglu, S.; Suphioglu, C.; Mikhail, E.; Gokhale, M. Exploring the Diagnostic Utility of Tear IgE and Lid Wiper Epitheliopathy in Ocular Allergy Among Individuals with Hay Fever. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghayan-Ugurluoglu, R.; Ball, T.; Vrtala, S.; Schweiger, C.; Kraft, D.; Valenta, R. Dissociation of allergen-specific IgE and IgA responses in sera and tears of pollen-allergic patients: A study performed with purified recombinant pollen allergens. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2000, 105, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, E.; Callahan, D.L.; Chong, L.; Azizoglu, S.; Gokhale, M.; Suphioglu, C. The Plight of the Metabolite: Oxidative Stress and Tear Film Destabilisation Evident in Ocular Allergy Sufferers across Seasons in Victoria, Australia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, E.; Nie, S.; Azizoglu, S.; Chong, L.; Gokhale, M.; Suphioglu, C. What’s the situation with ocular inflammation? A cross-seasonal investigation of proteomic changes in ocular allergy sufferers’ tears in Victoria, Australia. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1386344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nättinen, J.; Aapola, U.; Jylhä, A.; Vaajanen, A.; Uusitalo, H. Comparison of Capillary and Schirmer Strip Tear Fluid Sampling Methods Using SWATH-MS Proteomics Approach. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2020, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergouwen, D.P.C.; Schotting, A.J.; Endermann, T.; van de Werken, H.J.G.; Grashof, D.G.B.; Arumugam, S.; Nuijts, R.M.M.A.; Berge, J.C.T.; Rothova, A.; Schreurs, M.W.J.; et al. Evaluation of pre-processing methods for tear fluid proteomics using proximity extension assays. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Frenia, K.; Garwood, K.C.; Kimmel, J.; Labriola, L.T. High-Throughput Tear Proteomics via In-Capillary Digestion for Biomarker Discovery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, G.; Lee, T.J.; Glass, J.; Rountree, G.; Ulrich, L.; Estes, A.; Sezer, M.; Zhi, W.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, A. Comparison of Different Mass Spectrometry Workflows for the Proteomic Analysis of Tear Fluid. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harkness, B.M.; Hegarty, D.M.; Saugstad, J.A.; Behrens, H.; Betz, J.; David, L.L.; Lapidus, J.A.; Chen, S.; Stutzman, R.; Chamberlain, W.; et al. Experimental design considerations for studies of human tear proteins. Ocul. Surf. 2023, 28, 58–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, E.; Dhar, P.; Gokhale, M.; Chong, L.; Azizoglu, S.; Suphioglu, C. A Review of Emerging Tear Proteomics Research on the Ocular Surface in Ocular Allergy. Biology 2022, 11, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Zhang, H.; Xie, Z.; Liu, Y.; Gao, K.; Zhang, J.; Xie, S.; Wang, F.; Fan, R.; Jiang, W. Identification of Novel Biomarkers for Evaluating Disease Severity in House-Dust-Mite-Induced Allergic Rhinitis by Serum Metabolomics. Dis. Markers 2021, 2021, 5558458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.-J.; Zhang, J.-P.; Zhang, J.-H.; Han, Y.-L.; Xin, B.; Zhang, J.-X.; Bona, D.; Yuan, Z.; Cheng, G. Distinct Metabolic Profile of Inhaled Budesonide and Salbutamol in Asthmatic Children during Acute Exacerbation. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2017, 120, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.C.; Wang, T.S.; Wang, J.; Ma, Z.J.; Pu, S.B. Serum metabolomics study of patients with allergic rhinitis. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2020, 34, e4739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Yan, G.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, H.; Luo, W.; Xue, M.; Li, N.; Wu, J.-L.; Sun, B. Metabolomics Reveals Process of Allergic Rhinitis Patients with Single- and Double-Species Mite Subcutaneous Immunotherapy. Metabolites 2021, 11, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.-J.; Li, L.-S.; Sun, J.L.; Guan, K.; Wei, J.F. 1H NMR-based metabolomic study of metabolic profiling for pollinosis. World Allergy Organ. J. 2019, 12, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zhang, R.; Liu, G.; Yan, Z.; Hu, H.; Yu, S.; Jie, Z. Microarray analysis of differentially expressed microRNAs in allergic rhinitis. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2011, 25, e242–e246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suojalehto, H.; Toskala, E.; Kilpeläinen, M.; Majuri, M.; Mitts, C.; Lindström, I.; Puustinen, A.; Plosila, T.; Sipilä, J.; Wolff, H.; et al. MicroRNA Profiles in Nasal Mucosa of Patients with Allergic and Nonallergic Rhinitis and Asthma; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 612–620. [Google Scholar]

- Pua, H.H.; Steiner, D.F.; Patel, S.; Gonzalez, J.R.; Ortiz-Carpena, J.F.; Kageyama, R.; Chiou, N.-T.; Gallman, A.; de Kouchkovsky, D.; Jeker, L.T.; et al. MicroRNAs 24 and 27 suppress allergic inflammation and target a network of regulators of T helper 2 cell-associated cytokine production. Immunity 2016, 44, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, L.; Jiang, L.; Hu, Q.; Li, Y. MicroRNA-133b ameliorates allergic inflammation and symptom in murine model of allergic rhinitis by targeting Nlrp3. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 42, 901–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, E.; Azizoglu, S.; Chong, L.; Gokhale, M.; Suphioglu, C. microRNA-mediated allergic angiogenesis and inflammation evident in a preliminary study of the tears of patients with ocular allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vera-Montecinos, A.; Pardo, C.C.; Hernández, M.; Saldivia, P.; Nourdin, G.; Elizondo-Vega, R.; Sánchez, E.; Amulef, S.; Koch, E.; Vargas, C.; et al. High throughput tear proteomics with data independent acquisition enables biomarker discovery in allergic conditions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gijs, M.; Adelaar, T.I.; Vergouwen, D.P.C.; Visser, N.; Dickman, M.M.; Ollivier, R.C.I.; Berendschot, T.T.J.M.; Nuijts, R.M.M.A. Tear Fluid Inflammatory Proteome Analysis Highlights Similarities Between Keratoconus and Allergic Conjunctivitis. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2023, 64, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guéant, J.L.; Romano, A.; Cornejo-Garcia, J.A.; Oussalah, A.; Chery, C.; Blanca-López, N.; Guéant-Rodriguez, R.-M.; Gaeta, F.; Rouyer, P.; Josse, T.; et al. HLA-DRA variants predict penicillin allergy in genome-wide fine-mapping genotyping. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 135, 253–259.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willcox, M.D.P.; Morris, C.A.; Thakur, A.; Sack, R.A.; Wickson, J.; Boef, W. Complement and Complement Regulatory Proteins in Human Tears. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1997, 38, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Korkmaz, B.; Horwitz, M.S.; Jenne, D.E.; Gauthier, F. Neutrophil Elastase, Proteinase 3, and Cathepsin G as Therapeutic Targets in Human Diseases. Pharmacol. Rev. 2010, 62, 726–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sima, J.; Piao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Schlessinger, D. Molecular dynamics of Dkk4 modulates Wnt action and regulates meibomian gland development. Development 2016, 143, 4723–4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delalle, I.; Pfleger, C.M.; Buff, E.; Lueras, P.; Hariharan, I.K. Mutations in the Drosophila Orthologs of the F-Actin Capping Protein α- and β-Subunits Cause Actin Accumulation and Subsequent Retinal Degeneration. Genetics 2005, 171, 1757–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.M.; Bradford, H.N.; Isordia-Salas, I.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Espinola, R.G.; Ghebrehiwet, B.; Colman, R.W. High-Molecular-Weight Kininogen Fragments Stimulate the Secretion of Cytokines and Chemokines Through uPAR, Mac-1, and gC1qR in Monocytes. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006, 26, 2260–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Peng, R.; Chen, H.; Cui, C.; Ba, J.; Wang, F. Kininogen 1 and insulin-like growth factor binding protein 6: Candidate serum biomarkers of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2014, 97, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blom, A.M. The role of complement inhibitors beyond controlling inflammation. J. Intern. Med. 2017, 282, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baum, M.L.; Wilton, D.K.; Muthukumar, A.; Fox, R.G.; Carey, A.; Crotty, W.; Scott-Hewitt, N.; Bien, E.; Sabatini, D.A.; Lanser, T.; et al. CUB and Sushi Multiple Domains 1 (CSMD1) opposes the complement cascade in neural tissues. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Xiao, J.; Yi, J.; Xiao, J.; Lu, F.; Liu, X. Immunomodulatory Effect of Serum Exosomes From Crohn Disease on Macrophages via Let-7b-5p/TLR4 Signaling. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2022, 28, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalaimani, L.; Devarajan, B.; Namperumalsamy, V.P.; Veerappan, M.; Daniels, J.T.; Chidambaranathan, G.P. Hsa-miR-143-3p inhibits Wnt-β-catenin and MAPK signaling in human corneal epithelial stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Bi, Q.; Wang, X.; Liu, J. Down-regulation of mir-27b promotes angiogenesis and fibroblast activation through activating PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Wound Repair Regen. 2020, 28, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oltra, M.; Vidal-Gil, L.; Maisto, R.; Sancho-Pelluz, J.; Barcia, J.M. Oxidative stress-induced angiogenesis is mediated by miR-205-5p. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 1428–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Zhang, L.; Qi, R.; Qiu, L.; Gao, X.; Xiao, T.; Chen, H. miR-126-3p and miR-16-5p as novel serum biomarkers for disease activity and treatment response in symptomatic dermographism. Clin. Immunol. 2021, 222, 108636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Li, C.; Xu, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, X. LncRNA LINC01123 promotes malignancy of ovarian cancer by targeting hsa-miR-516b-5p/VEGFA. Genes Genom. 2023, 46, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, J.; Yu, Z.; de Paiva, C.S.; Pflugfelder, S.C. Retinoid Regulation of Ocular Surface Innate Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldogh, I.; Bacsi, A.; Choudhury, B.K.; Dharajiya, N.; Alam, R.; Hazra, T.K.; Mitra, S.; Goldblum, R.M.; Sur, S. ROS generated by pollen NADPH oxidase provide a signal that augments antigen-induced allergic airway inflammation. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 2169–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, J.P.; Tomlinson, A. Importance of the lipid layer in human tear film stability and evaporation. Optom. Vis. Sci. 1997, 74, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMonnies, C.W. Eye rubbing type and prevalence including contact lens “removal-relief” rubbing. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2016, 99, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, S.A.; Pye, D.C.; Willcox, M.D.P. Effects of eye rubbing on the levels of protease, protease activity and cytokines in tears: Relevance in keratoconus. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2013, 96, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jere, S.W.; Abrahamse, H.; Houreld, N.N. Interaction of the AKT and β-catenin signalling pathways and the influence of photobiomodulation on cellular signalling proteins in diabetic wound healing. J. Biomed. Sci. 2023, 30, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Li, S.; Li, J.; Huang, C.; Zhou, F.; Zhao, L.; Yu, W.; Qin, X. Knockdown of Fibromodulin Inhibits Proliferation and Migration of RPE Cell via the VEGFR2-AKT Pathway. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 2018, 5708537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Bove, A.M.; Simone, G.; Ma, B. Molecular Bases of VEGFR-2-Mediated Physiological Function and Pathological Role. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 599281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, S.S.; Pan, Y.M.; Yang, W.J.; Rao, Z.Q.; Yang, Y.N. Inhibition of EZH2 alleviates angiogenesis in a model of corneal neovascularization by blocking FoxO3a-mediated oxidative stress. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 10168–10181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grange, P.; Raingeaud, J.; Calvez, V.; Dupin, N. Nicotinamide inhibits Propionibacterium acnes-induced IL-8 production in keratinocytes through the NF-kappaB and MAPK pathways. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2009, 56, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagdic, A.; Sener, O.; Bulucu, F.; Karadurmus, N.; Özel, H.E.; Yamanel, L.; Tasci, C.; Naharci, I.; Ocal, R.; Aydin, A. Oxidative stress status and plasma trace elements in patients with asthma or allergic rhinitis. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2011, 39, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Niu, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, S.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Gong, L. Role of the mucin-like glycoprotein FCGBP in mucosal immunity and cancer. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 863317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzalyova, A.; Brunner, J.O. Determinants of the utilization of allergy management measures among hay fever sufferers: A theory-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Schiemann, W.P. Fibromodulin Suppresses Nuclear Factor-κB Activity by Inducing the Delayed Degradation of IKBA via a JNK-dependent Pathway Coupled to Fibroblast Apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 6414–6422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, F.E.C.; Covre, J.L.; Ramos, L.; Hazarbassanov, R.M.; Santos MSdos Campos, M.; Gomes, J.Á.P.; Gil, C.D. Evaluation of galectin-1 and galectin-3 as prospective biomarkers in keratoconus. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 102, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimmura-Tomita, M.; Wang, M.; Taniguchi, H.; Akiba, H.; Yagita, H.; Hori, J. Galectin-9-Mediated Protection from Allo-Specific T Cells as a Mechanism of Immune Privilege of Corneal Allografts. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlfart, S.; Meiller, R.; Hammersen, J.; Park, J.; Menzel-Severing, J.; Melichar, V.O.; Huttner, K.; Johnson, R.; Porte, F.; Schneider, H. Natural history of X-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia: A 5-year follow-up study. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2020, 15, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Gao, N.; Wang, D.; Pazo, E.E.; Qi, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, C.; Yang, R. Differential Expression of Tear Lymphotoxin-A, Immunoglobulin E, and Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 in Allergic Conjunctivitis-Associated Dry Eye. Curr. Eye Res. 2025, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente, M.; Rodríguez-Agirretxe, I.; Vecino, E.; Astigarraga, E.; Acera, A.; Barreda-Gómez, G. Elevation of Tear MMP-9 Concentration as a Biomarker of Inflammation in Ocular Pathology by Antibody Microarray Immunodetection Assays. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Analyte | Biomarker | Regulation in OA | Primary Biopathway(s) | Proposed Role on the Ocular Surface |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins | HLA class II histocompatibility antigen DRB5 beta chain (HLA-DRB5) | Upregulated | Immune response | Enhanced antigen presentation to CD4+ T cells, contributing to amplification of allergic inflammation [32,34] |

| Dipeptidyl peptidase (CTSC1) | Upregulated | Immune response, inflammation | Regulation of innate immunity and neutrophil activation, facilitating clearance of allergenic peptides [15,35,36] | |

| Complement component 9 (C9) | Upregulated | Immune response, inflammation | Activation of complement-mediated inflammatory responses [31,35,36] | |

| Fibromodulin (FMOD) | Upregulated | Wound healing, angiogenesis, inflammation | Extracellular matrix organisation, fibroblast activation, angiogenesis and modulation of inflammatory responses [15] | |

| IgGFc-binding protein (FCGBP) | Upregulated | Inflammation, homeostasis | Mucosal epithelial defence with cytoprotective and anti-inflammatory functions [32] | |

| Zinc Finger, FYVE Domain Containing 19 (ZFYVE19) | Upregulated | Wound healing | Regulation of cytokinesis and epithelial cell proliferation [32] | |

| Dickkopf-related protein 4 (DKK4) | Upregulated | Wound healing | Inhibition of Wnt signalling [15,37] | |

| F-actin capping protein subunit alpha (CAPZA 1/2) | Downregulated | Cytoskeletal integrity, inflammation | Indicative of cell structure disruption due to inflammation and mechanical stress (eye rubbing) [15,38] | |

| Moesin (MSN) | Downregulated | Homeostasis | Cytoskeletal organisation and maintenance of epithelial stability [15] | |

| ELAV-like protein 1 (ELAV1) | Downregulated | Homeostasis | Post-transcriptional regulation of inflammatory mediators [15] | |

| TRNA Nucleotidyl Transferase 1 (TRNT1) | Dysregulated | Inflammation | Regulation of tRNA maturation and cellular stress responses [32] | |

| Ras-related protein 25 (RAB25) | Dysregulated | Inflammation | Regulation of vesicle trafficking and epithelial polarity [32] | |

| Kininogen-1 (KNG1) | Dysregulated (downregulated in OA) | Inflammation, wound healing | Regulation of inflammatory cascades and vascular permeability [15,39,40,41,42] | |

| CUB And Sushi Multiple Domains 1 (CSMD1) | Dysregulated (downregulated in OA) | Inflammation, angiogenesis | Modulation of complement activation and inflammatory signalling [15,39,40,41,42] | |

| miRNAs | let-7 family (e.g., let-7b-5p) | Upregulated | Inflammation, homeostasis | Anti-inflammatory regulation and facilitation of return to homeostasis [31,43] |

| miR-143-3p | Downregulated | Wound healing | Reduced inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signalling, favouring epithelial proliferation [31,44] | |

| miR-27b-5p | Downregulated | Inflammation | Promotion of fibroblast activation and proinflammatory cytokine release [31,45] | |

| miR-142-5p | Downregulated | Inflammation | Modulation of immune cell activation and cytokine expression [31] | |

| miR-221-3p | Downregulated | Inflammation | Regulation of inflammatory signalling pathways [31] | |

| miR-223-3p | Downregulated | Inflammation | Control of innate immune responses [31] | |

| miR-205-5p | Dysregulated | Wound healing, angiogenesis, inflammation | Regulation of epithelial repair, VEGF signalling and inflammatory mediator expression [31,46,47,48] | |

| miR-126-3p | Dysregulated | Angiogenesis, inflammation | Modulation of VEGF-driven angiogenesis and endothelial function [31,46,47,48] | |

| miR-516b-5p | Dysregulated | Angiogenesis | Regulation of VEGF expression and neovascularization [31,46,47,48] | |

| miR-574-5p | Dysregulated | Inflammation | Modulation of inflammatory signalling pathways, including regulation of NF-κB-associated cytokine expression [31] | |

| Metabolites/Pathways | Vitamin A | Upregulated | Homeostasis, anti-inflammation | Tear film maintenance and anti-inflammatory compensation [14,49] |

| FOXO regulation | Upregulated | Oxidative stress, angiogenesis | Regulation of oxidative stress responses and antioxidant secretion [14,46,50] | |

| Niacinamide/Vitamin B3 | Dysregulated | Inflammation, oxidative stress | Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity [14] | |

| Theanine | Dysregulated | Inflammation, oxidative stress | Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity [14] | |

| Lipids | Choline-derived lipids | Downregulated | Tear film stability, oxidative stress | Reduced tear film stability and increased evaporation [14,51] |

| Phosphatidylcholine/Phosphatidylethanolamine | Downregulated | Tear film integrity | Altered lipid layer composition contributing to inflammation and dry eye [14,51] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Aydin, E.; Azizoglu, S.; Chong, L.; Gokhale, M.; Suphioglu, C. From Proteome to miRNome: A Review of Multi-Omics Ocular Allergy Research Using Human Tears. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 671. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020671

Aydin E, Azizoglu S, Chong L, Gokhale M, Suphioglu C. From Proteome to miRNome: A Review of Multi-Omics Ocular Allergy Research Using Human Tears. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):671. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020671

Chicago/Turabian StyleAydin, Esrin, Serap Azizoglu, Luke Chong, Moneisha Gokhale, and Cenk Suphioglu. 2026. "From Proteome to miRNome: A Review of Multi-Omics Ocular Allergy Research Using Human Tears" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 671. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020671

APA StyleAydin, E., Azizoglu, S., Chong, L., Gokhale, M., & Suphioglu, C. (2026). From Proteome to miRNome: A Review of Multi-Omics Ocular Allergy Research Using Human Tears. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 671. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020671