Approach to Design of Potent RNA Interference-Based Preparations Against Hepatocellular Carcinoma-Related Genes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Design of siRNA Sequences

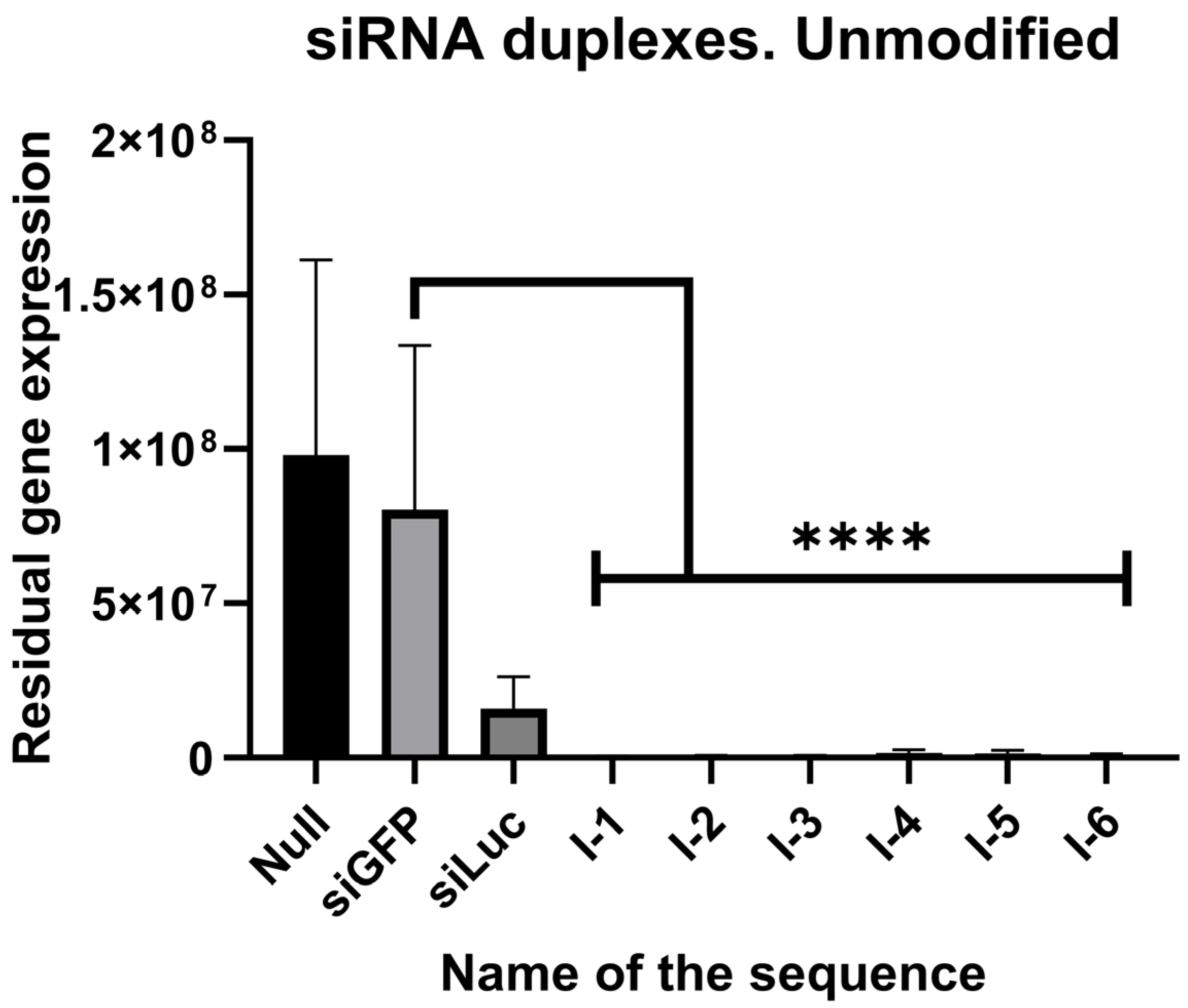

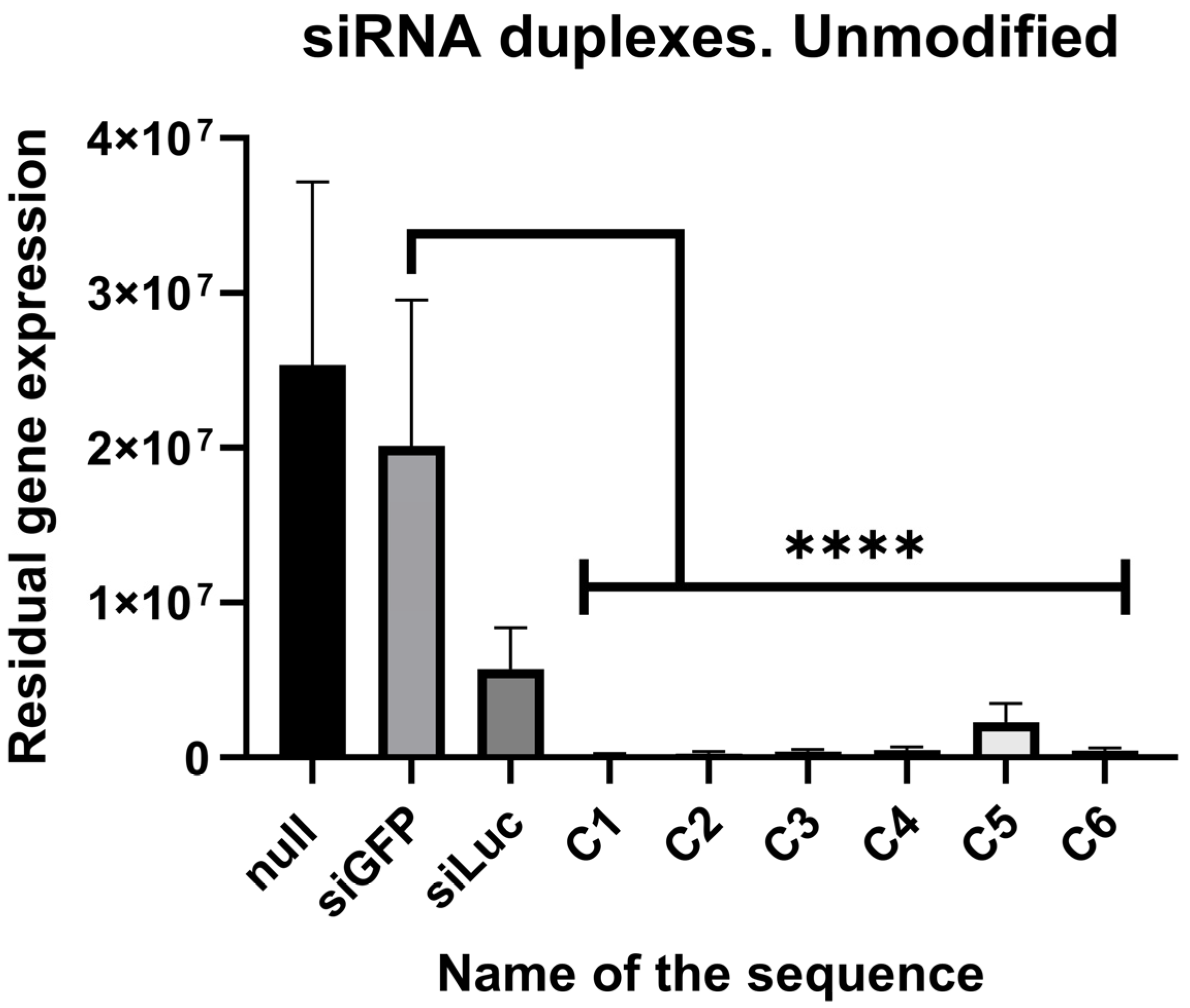

2.2. In Vitro Screening of Ribose Duplexes

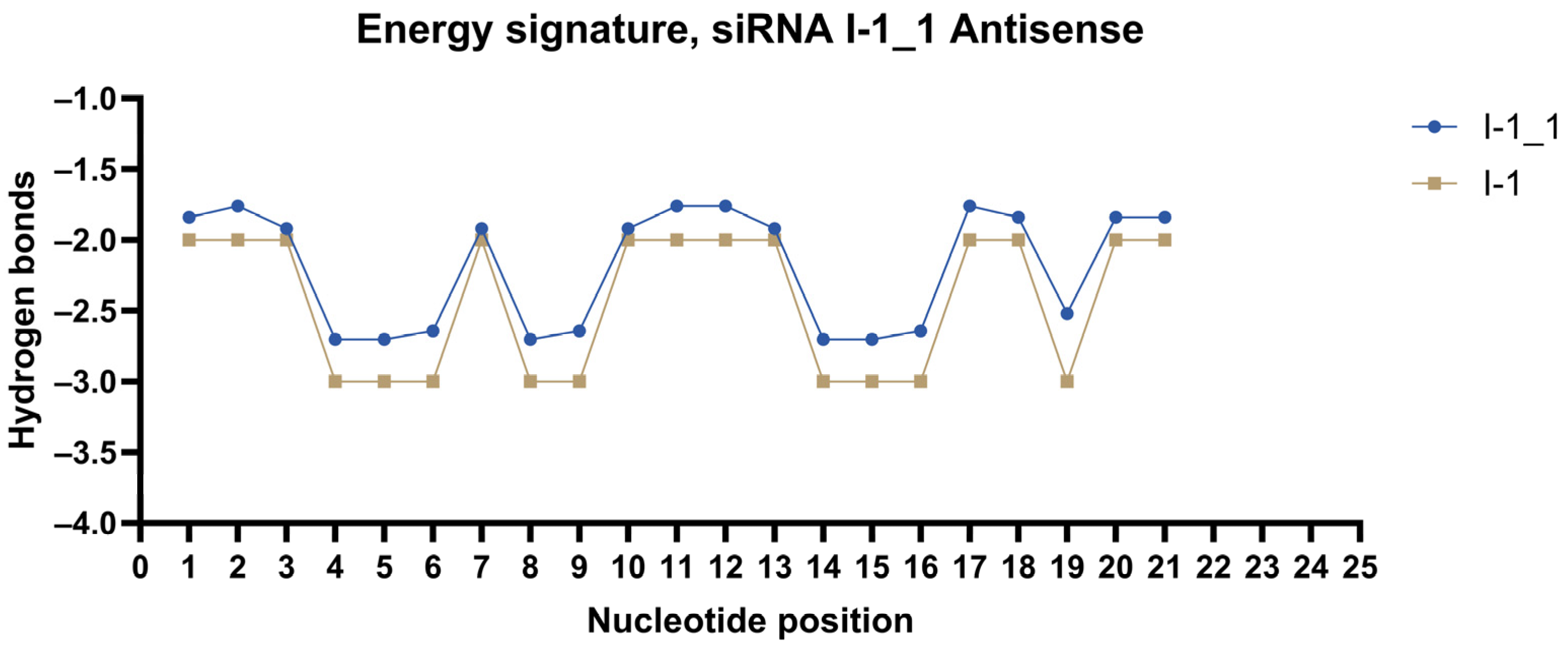

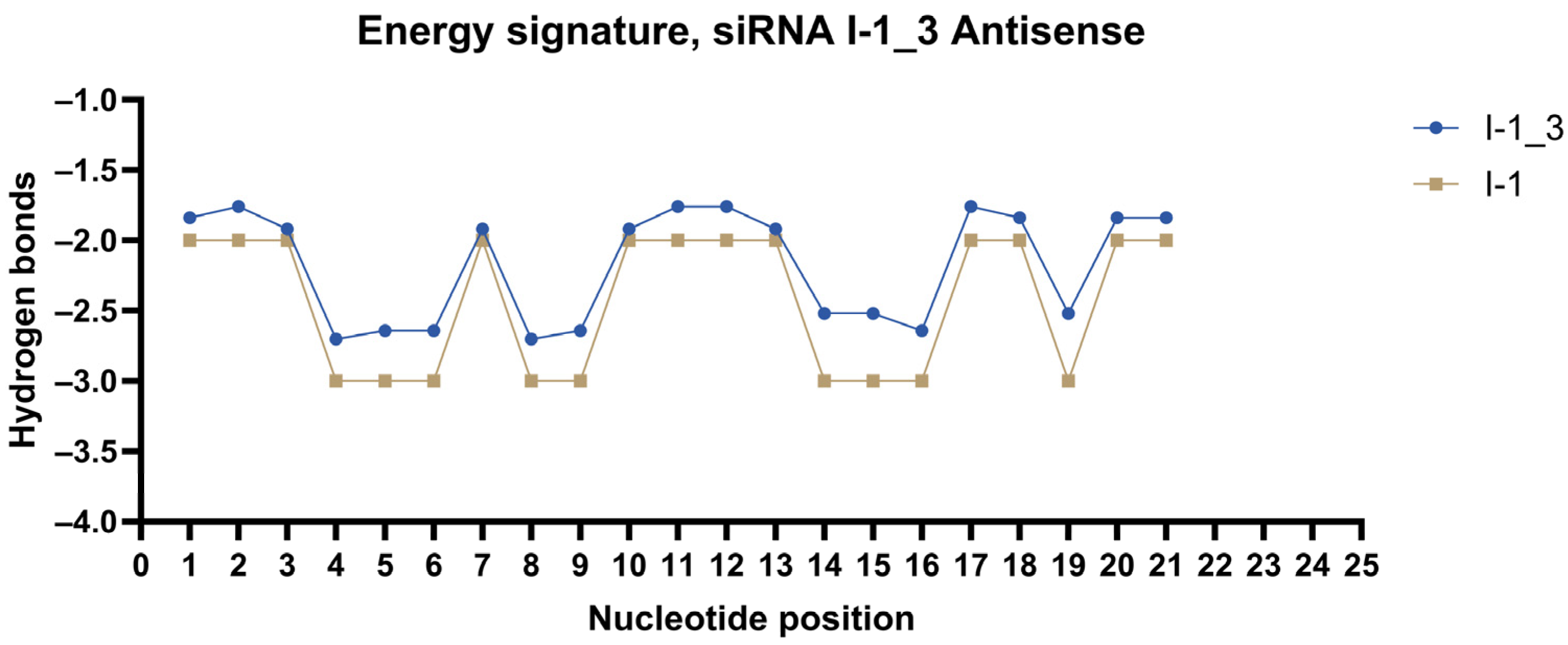

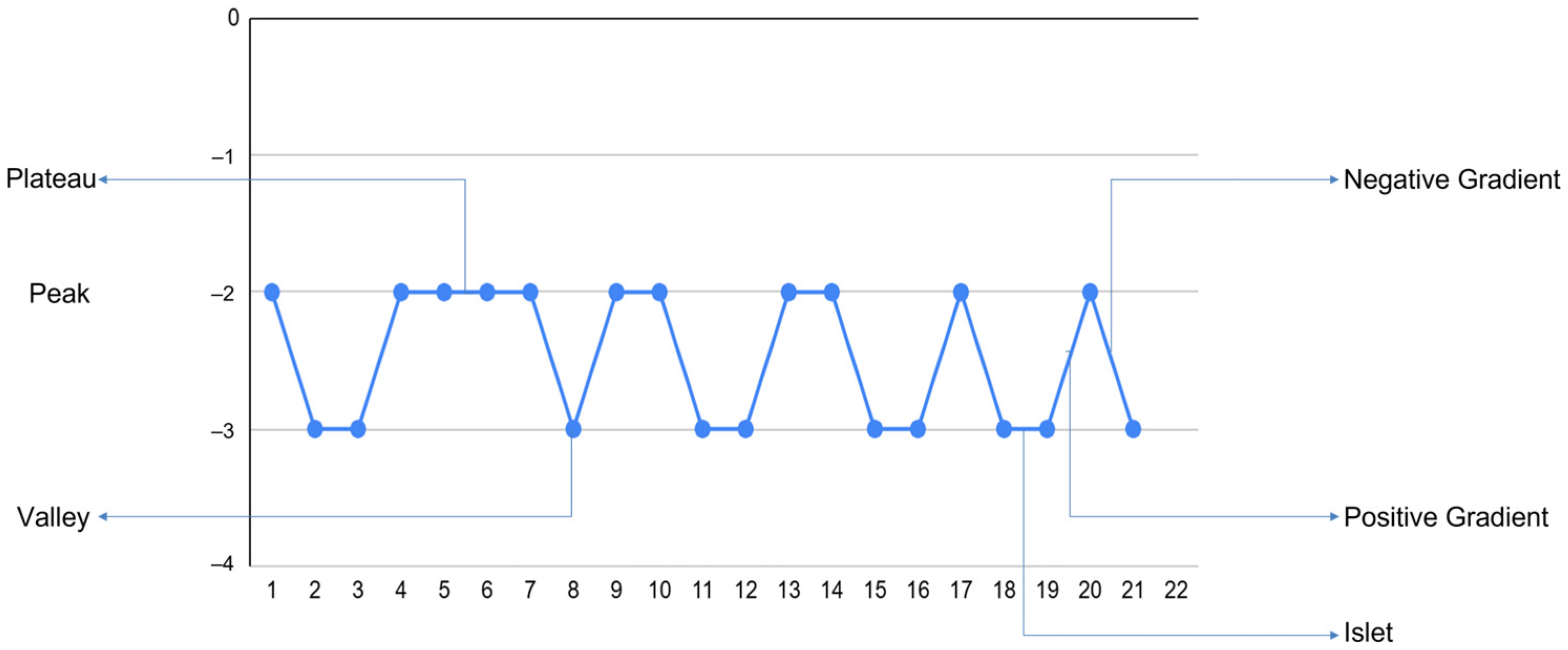

2.3. Design of siRNA Modifications

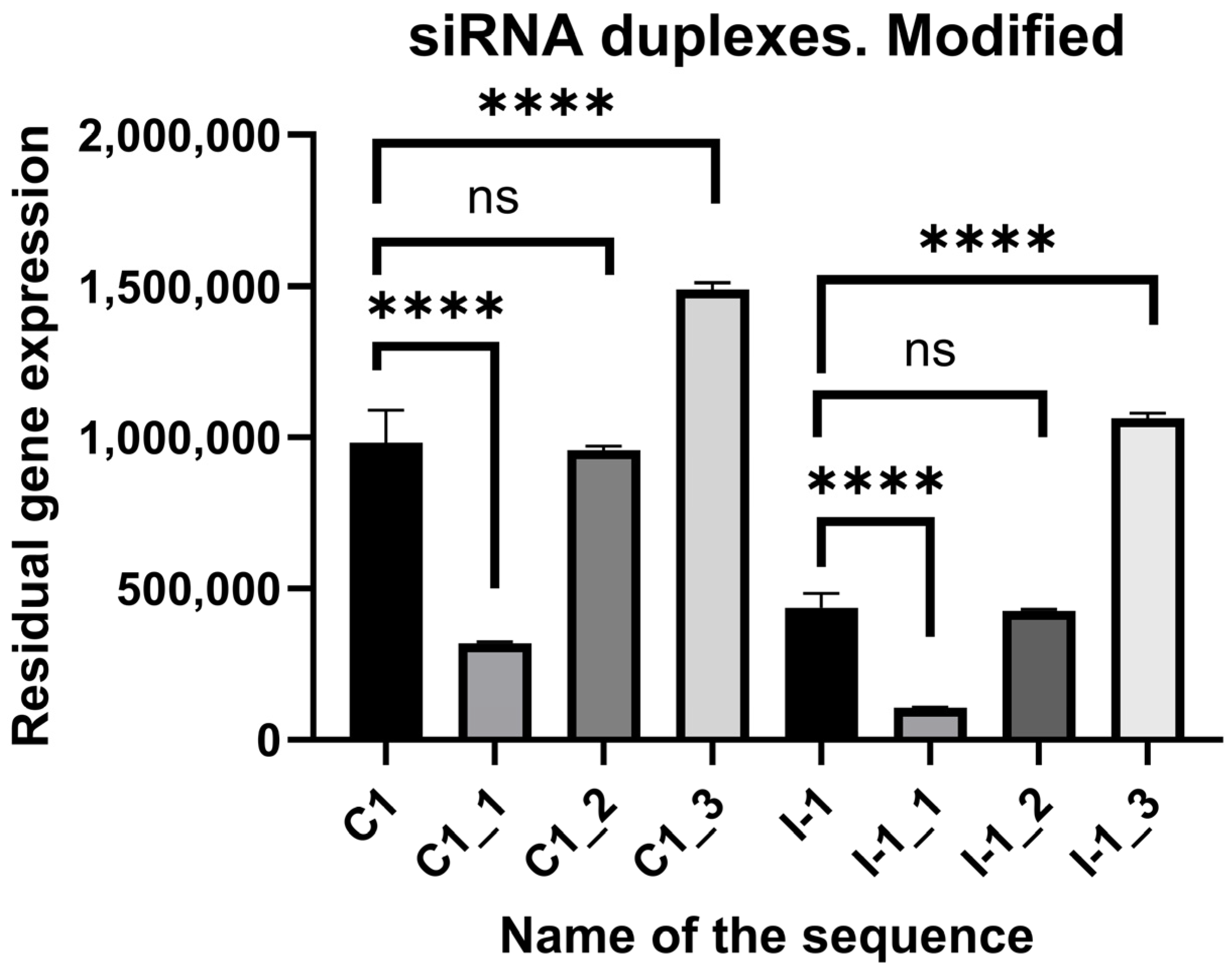

2.4. In Vitro Screening of Modified siRNAs

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Design of siRNA Sequences

4.2. Modification of the siRNAs

4.3. Automated Solid-Phase Oligonucleotide Synthesis, Chromatographic Purification, Physico-Chemical Characterization

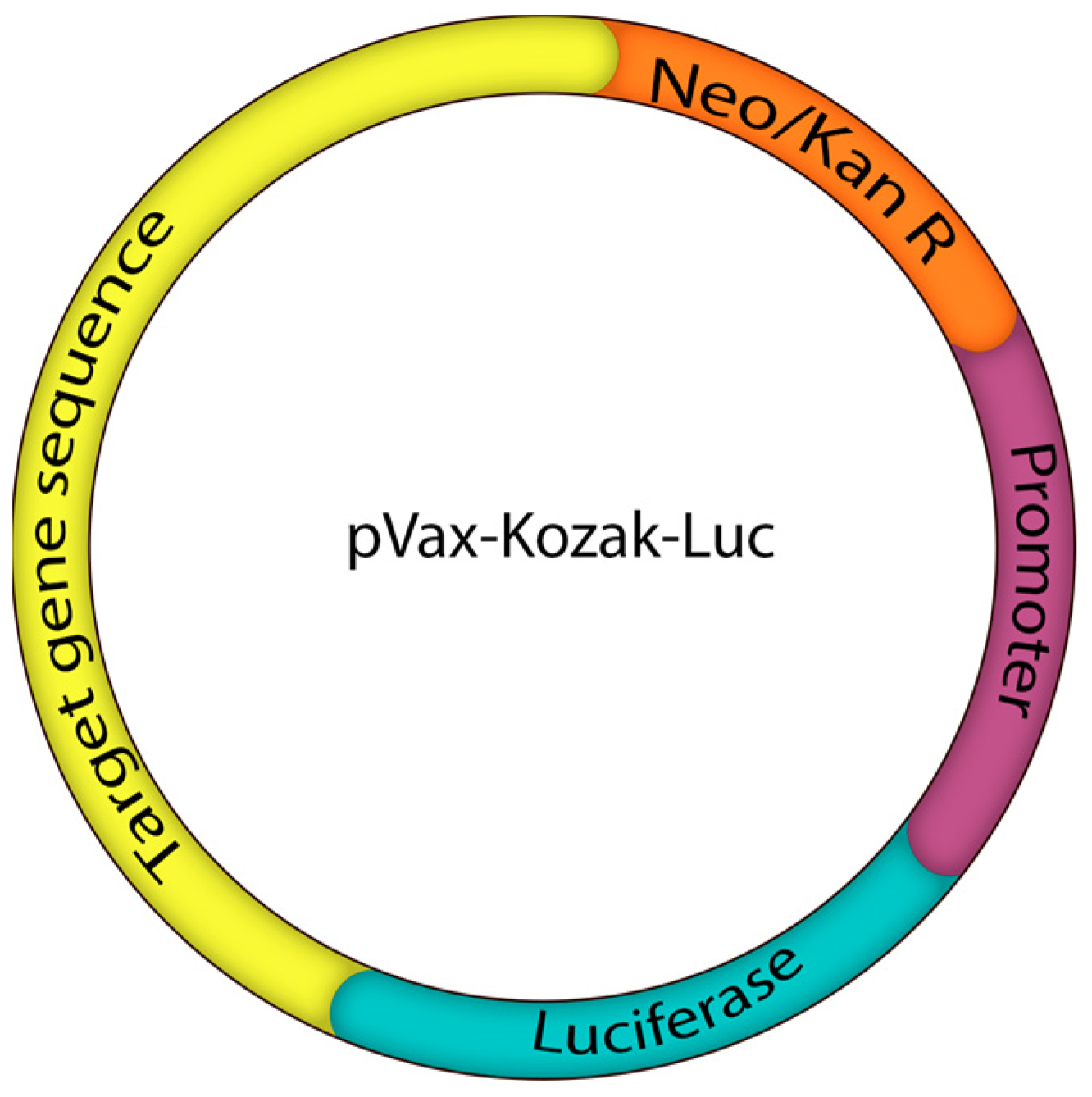

4.4. Reporter Plasmids

4.5. In Vitro Study

4.6. Statistical Evaluation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| ASO | Antisense Oligonucleotide |

| CD | Cluster of Differentiation |

| CMV | Cytomegalovirus |

| CTLA | Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte-Associated Protein |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| ECAM | Extracellular Adhesion Molecule |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration (USA) |

| FMBA | Federal Medical–Biological Agency (Russia) |

| HCC | Hepatocellular Carcinoma |

| HEK | Human Embryonic Kidney |

| HEPES | (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid) |

| IAP | Integrin-Associated Protein |

| ITGB | Integrin Subunit Beta |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| MALDI-ToF | Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization—Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| NRC | National Research Center |

| PD-1 | Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed Death-Ligand 1 |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| RNAi | RNA Interference |

| RISC | RNA-Induced Silencing Complex |

| SIRPα | Signal Regulatory Protein Alpha |

| siRNA | Small Interfering RNA |

| UTR | Untranslated Region |

| 2′-F | 2′-Fluorinated nucleotide |

| 2′-OMe | 2′-O-Methylated nucleotide |

References

- Bertuccio, P.; Turati, F.; Carioli, G.; Rodriguez, T.; La Vecchia, C.; Malvezzi, M.; Negri, E. Global Trends and Predictions in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Mortality. J. Hepatol. 2017, 67, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.-J.; Ip, E.W.K.; Fong, Y. Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Current Surgical Management. Gastroenterology 2004, 127, S248–S260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.; Dawson, L.A. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Radiation Therapy: Review of Evidence and Future Opportunities. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2013, 87, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Han, J.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Y. PD-1/PD-L1 Checkpoint Inhibitors in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1070961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, N.; Dasaradhi, P.V.N.; Mohmmed, A.; Malhotra, P.; Bhatnagar, R.K.; Mukherjee, S.K. RNA Interference: Biology, Mechanism, and Applications. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2003, 67, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott, D.; Yanai, I.; Hunter, C.P. Natural RNA Interference Directs a Heritable Response to the Environment. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 7387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leitão, A.L.; Enguita, F.J. A Structural View of MiRNA Biogenesis and Function. Noncoding RNA 2022, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauffer, M.C.; van Roon-Mom, W.; Aartsma-Rus, A. Possibilities and Limitations of Antisense Oligonucleotide Therapies for the Treatment of Monogenic Disorders. Commun. Med. 2024, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crater, A.K.; Roscoe, S.; Roberts, M.; Ananvoranich, S. Antisense Technologies in the Studying of Toxoplasma Gondii. J. Microbiol. Methods 2017, 138, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Guo, Q.; Luo, Q. Inhibition of ITGB1-DT Expression Delays the Growth and Migration of Stomach Adenocarcinoma and Improves the Prognosis of Cancer Patients Using the Bioinformatics and Cell Model Analysis. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2022, 13, 615–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sudani, H.; Ni, Y.; Jones, P.; Karakilic, H.; Cui, L.; Johnson, L.D.S.; Rose, P.G.; Olawaiye, A.; Edwards, R.P.; Uger, R.A.; et al. Targeting CD47-SIRPa Axis Shows Potent Preclinical Anti-Tumor Activity as Monotherapy and Synergizes with PARP Inhibition. npj Precis. Oncol. 2023, 7, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zou, W. Inhibition of Integrin Β1 Decreases the Malignancy of Ovarian Cancer Cells and Potentiates Anticancer Therapy via the FAK/STAT1 Signaling Pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 7869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Mo, J.; Dong, S.; Liao, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, P. Integrinβ-1 in Disorders and Cancers: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, A.P.Y.; Khavkine Binstock, S.S.; Thu, K.L. CD47: The Next Frontier in Immune Checkpoint Blockade for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 5229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.; Rennhack, J.; Mok, S.; Ling, C.; Perez, M.; Roccamo, J.; Andrechek, E.R.; Moraes, C.; Muller, W.J. Functional Redundancy between Β1 and Β3 Integrin in Activating the IR/Akt/MTORC1 Signaling Axis to Promote ErbB2-Driven Breast Cancer. Cell Rep. 2019, 29, 589–602.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, X.; Yan, B.; Tian, X.; Liu, Q.; Jin, J.; Shi, J.; Hou, Y. CD47/SIRPα Pathway Mediates Cancer Immune Escape and Immunotherapy. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 17, 3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaitov, M.; Nikonova, A.; Shilovskiy, I.; Kozhikhova, K.; Kofiadi, I.; Vishnyakova, L.; Nikolskii, A.; Gattinger, P.; Kovchina, V.; Barvinskaia, E.; et al. Silencing of SARS-CoV-2 with Modified SiRNA-Peptide Dendrimer Formulation. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 76, 2840–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, J.; Zhang, T.; Xue, J.; Liu, S.; Gao, H.; Zhang, Z.Z.Z.; Wu, J.; et al. Mechanistic Insights into RNA Cleavage by Human Argonaute2–SiRNA Complex. Cell Res. 2025, 35, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliuchnikov, E.; Maksudov, F.; Zuber, J.; Hyde, S.; Castoreno, A.; Waldron, S.; Schlegel, M.K.; Marx, K.A.; Maier, M.A.; Barsegov, V. Improving the Potency Prediction for Chemically Modified SiRNAs through Insights from Molecular Modeling of Individual Sequence Positions. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2025, 36, 102415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimbrough, E.M.; Nguyen, H.A.; Li, H.; Mattingly, J.M.; Bailey, N.A.; Ning, W.; Gamper, H.; Hou, Y.M.; Gonzalez, R.L.; Dunham, C.M. An RNA Modification Prevents Extended Codon-Anticodon Interactions from Facilitating +1 Frameshifting. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manickam, N.; Joshi, K.; Bhatt, M.J.; Farabaugh, P.J. Effects of TRNA Modification on Translational Accuracy Depend on Intrinsic Codon–Anticodon Strength. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 44, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ui-Tei, K.; Naito, Y.; Takahashi, F.; Haraguchi, T.; Ohki-Hamazaki, H.; Juni, A.; Ueda, R.; Saigo, K. Guidelines for the Selection of Highly Effective SiRNA Sequences for Mammalian and Chick RNA Interference. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 936–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A.; Leake, D.; Boese, Q.; Scaringe, S.; Marshall, W.S.; Khvorova, A. Rational SiRNA Design for RNA Interference. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004, 22, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarzguioui, M.; Prydz, H. An Algorithm for Selection of Functional SiRNA Sequences. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 316, 1050–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernov, P.V.; Dmitriev, N.A.; Gusev, A.E.; Kholstov, A.V.; Khodzhava, M.V.; Kovchina, V.I.; Rusak, T.E.; Kudlay, D.A.; Shilovskiy, I.P.; Kofiadi, I.A. Development and Validation of Algorithms for the Search, Evaluation and Modification of SiRNAs Applicable to the Treatment of Pathologies of the Immune System Using the Model of the APOB Gene. Immunologiya 2025, 46, 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Manton, J.D.; Ostrovsky, A.D.; Prohaska, S.; Jefferis, G.S. NBLAST: Rapid, Sensitive Comparison of Neuronal Structure and Construction of Neuron Family Databases. Neuron 2016, 91, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuker, M. Mfold Web Server for Nucleic Acid Folding and Hybridization Prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 3406–3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ATDBio. Nucleic Acids Book; Chapter 5: Solid-Phase Oligonucleotide Synthesis. Available online: https://atdbio.com/nucleic-acids-book/Solid-phase-oligonucleotide-synthesis (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Glen Report 22.210: Glen-PakTM Product Update: New Protocols for Purification. Available online: https://www.glenresearch.com/reports/gr22-210 (accessed on 22 November 2025).

| Name | Antisense 5′-3′ | Sense 5′-3′ |

|---|---|---|

| I-1 | UUUGCAUUCAGUGUUGUGGGA | CCACAACACUGAAUGCAAAGU |

| I-2 | UUAAAAGCUUCCAUAUCAGCA | CUGAUAUGGAAGCUUUUAAUG |

| I-3 | UCCUUAACUAGCUAGCAGGAC | CCUGCUAGCUAGUUAAGGAUU |

| I-4 | UAAAAAGGCAAAUUGACCGCU | CGGUCAAUUUGCCUUUUUAAU |

| I-5 | AAAACAAGAAUGUGACUAGUG | CUAGUCACAUUCUUGUUUUAA |

| I-6 | AAUACAUCAGAGUCAAGACAU | GUCUUGACUCUGAUGUAUUUU |

| C1 | UAACUAACAAUCACGUAAGGG | CUUACGUGAUUGUUAGUUAAG |

| C2 | UGACAGUGAUCACUAGUCCAG | GGACUAGUGAUCACUGUCAUU |

| C3 | UUUUCAUAGAUAUCUCUGGGU | CCAGAGAUAUCUAUGAAAACC |

| C4 | UCAAGAAGAGCUGUCUUGCUA | GCAAGACAGCUCUUCUUGAAA |

| C5 | UUAAAAGGUACAACUUUAGUU | CUAAAGUUGUACCUUUUAAUA |

| C6 | AGUGCAAAUAACAAUUUGGUG | CCAAAUUGUUAUUUGCACUAA |

| pVax + 0 | siGFP | siLuc | I-1 | I-2 | I-3 | I-4 | I-5 | I-6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.816 | 0.183 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.018 | 0.016 | 0.008 |

| Null | siGFP | siLuc | C-1 | C-2 | C-3 | C-4 | C-5 | C-6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.796 | 0.235 | 0.009 | 0.015 | 0.018 | 0.0273 | 0.098 | 0.022 |

| Name | Antisense 5′-3′ | Sense 5′-3′ |

|---|---|---|

| I-1 | rUrUrUrGrCrArUrUrCrArGrUrGrUrUrGrUrGrGrGrA | rCrCrArCrArArCrArCrUrGrArArUrGrCrArArArGrU |

| I-1_1 | mUmUmUmGmCmAmUmUmCmAmGmUmGmUmUmGmUmGmGmGmA | mCmCmAmCmAmAmCmAmCmUmGmAmAmUmGmCmAmAmAmGmU |

| I-1_2 | mUfUfUmGmCmAfUmUmCfAmGmUmGmUfUmGmUmGfGfGmA | fCfCmAmCmAmAmfCmAmCmUfGmAmAmUmGfCmAmAmAmGmU |

| I-1_3 | fUfUmUmGmCmAfUfUmCfAmGmUmGmUfUmGmUmGfGfGmA | fCdCmAmCmAmAfCmAmCdTmGmAmAmUmGfCfAmAmAmGmU |

| C1 | rUrArArCrUrArArCrArArUrCrArCrGrUrArArGrGrG | rCrUrUrArCrGrUrGrArUrUrGrUrUrArGrUrUrArArG |

| C1_1 | mUmAmAmCmUmAmAmCmAmAmUmCmAmCmGmUmAmAmGmGmG | mCmUmUmAmCmGmUmGmAmUmUmGmUmUmAmGmUmUmAmAmG |

| C1_2 | mUfAmAmCmUfAmAmCmAfAmUmCmAfCfGmUfAmAmGfGfG | fCfUfUmAmCmGmUmGfAfUmUmGmUmUmAmGmUmUmAfAfG |

| C1_3 | mUmAfAmCmUmAfAmCmAfAmUmCmAfCfGmUmAfAmGmGdA | fCdTmUmAmCmGmUmGmAdTmUmGmUdTmAmGmUmUmAfAfG |

| Criterion | Value | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Content of GC in the antisense strand | 36–52% of the strand | 1 |

| Amount of GC and AU repeats in the antisense strand | GC repeats < 3, AU repeats < 4 | 1 |

| Low GC content in 9–14 positions of antisense strand | GC content in 9–14 < GCcontent/2 | 2 |

| Number of A/U in positions 13–19 of the antisense strand | At least 3 | 1 |

| G/C at position 1 of the sense strand | Yes | 1 |

| A/U at position 10 of the sense strand | Yes | 1 |

| A at positions 3 and 19 of the sense strand | Yes | 1 |

| Absence of G/C at position 19 of the sense strand | Yes | 1 |

| Absence of G at position 13 of the sense strand | Yes | 1 |

| A/U at position 1 of the antisense strand | Yes | 1 |

| A at position 6 of the antisense strand | Yes | 1 |

| Content of GC in positions 2–7 and 8–18 of the antisense strand | GCcontent in positions 2–7 < 19%, GCcontent in positions 8–18 < 52% | 1 |

| Successful mFold | No annealing to thermodynamically rigid segments of mRNA | 1 |

| Successful BLAST | No significant off-target effects | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chernov, P.V.; Ivanov, V.N.; Dmitriev, N.A.; Gusev, A.E.; Kovchina, V.I.; Gongadze, I.S.; Kholstov, A.V.; Popova, M.V.; Kudlay, D.A.; Kryuchko, D.S.; et al. Approach to Design of Potent RNA Interference-Based Preparations Against Hepatocellular Carcinoma-Related Genes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 603. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020603

Chernov PV, Ivanov VN, Dmitriev NA, Gusev AE, Kovchina VI, Gongadze IS, Kholstov AV, Popova MV, Kudlay DA, Kryuchko DS, et al. Approach to Design of Potent RNA Interference-Based Preparations Against Hepatocellular Carcinoma-Related Genes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):603. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020603

Chicago/Turabian StyleChernov, Petr V., Vladimir N. Ivanov, Nikolai A. Dmitriev, Artem E. Gusev, Valeriia I. Kovchina, Ivan S. Gongadze, Alexander V. Kholstov, Maiia V. Popova, Dmitry A. Kudlay, Daria S. Kryuchko, and et al. 2026. "Approach to Design of Potent RNA Interference-Based Preparations Against Hepatocellular Carcinoma-Related Genes" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 603. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020603

APA StyleChernov, P. V., Ivanov, V. N., Dmitriev, N. A., Gusev, A. E., Kovchina, V. I., Gongadze, I. S., Kholstov, A. V., Popova, M. V., Kudlay, D. A., Kryuchko, D. S., Kofiadi, I. A., & Khaitov, M. R. (2026). Approach to Design of Potent RNA Interference-Based Preparations Against Hepatocellular Carcinoma-Related Genes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 603. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020603