Antiprotozoal Potential of Cultivated Geranium macrorrhizum Against Giardia duodenalis, Trichomonas gallinae and Leishmania infantum

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Antiparasitic Activity of Essential Oils from G. macrorrhizum

2.2. Chemical Composition of G. macrorrhizum EOs

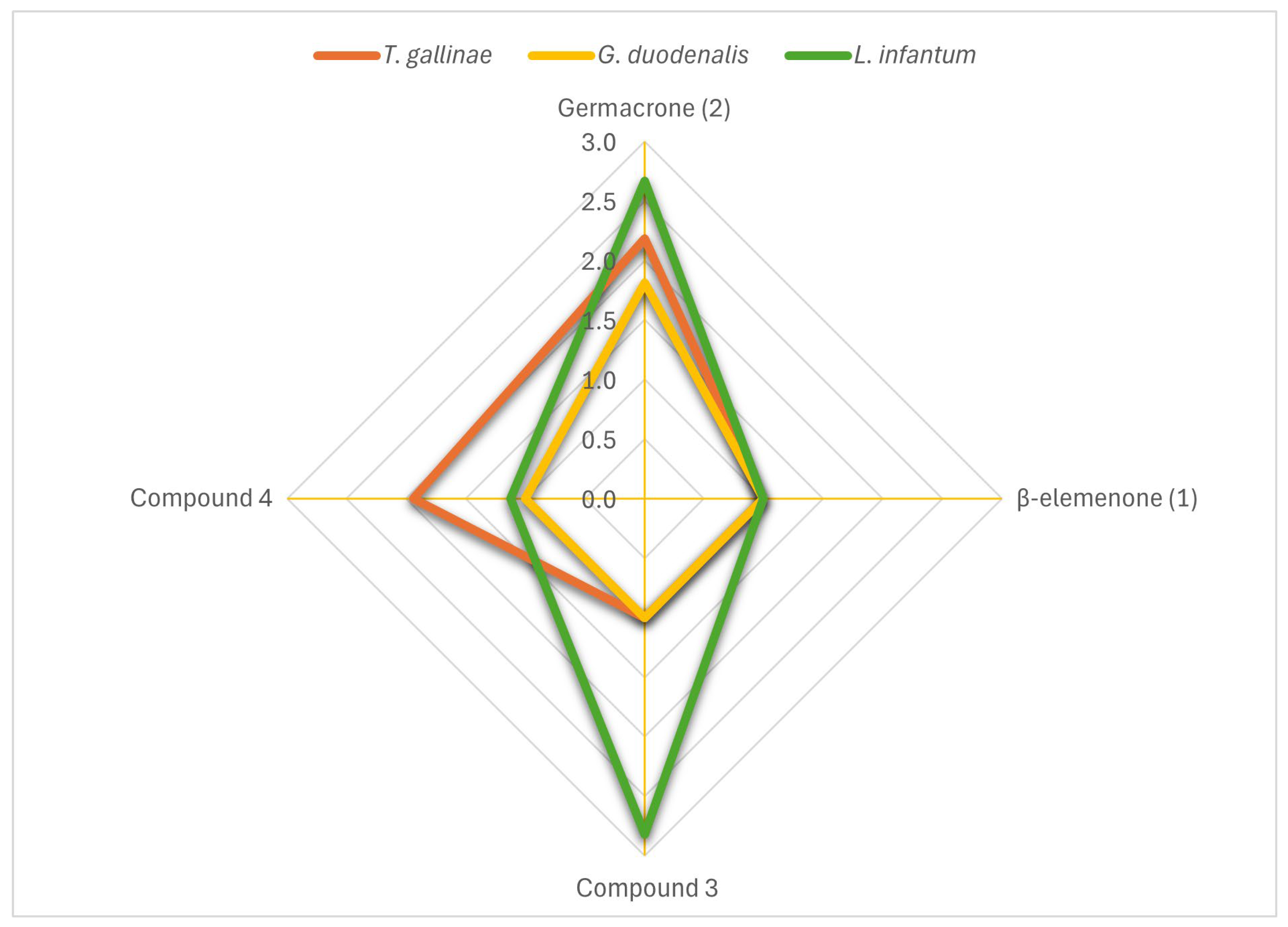

2.3. Antiparasitic and Cytotoxic Properties of G. macrorrhizum Main Compounds Against Extracellular Protozoa

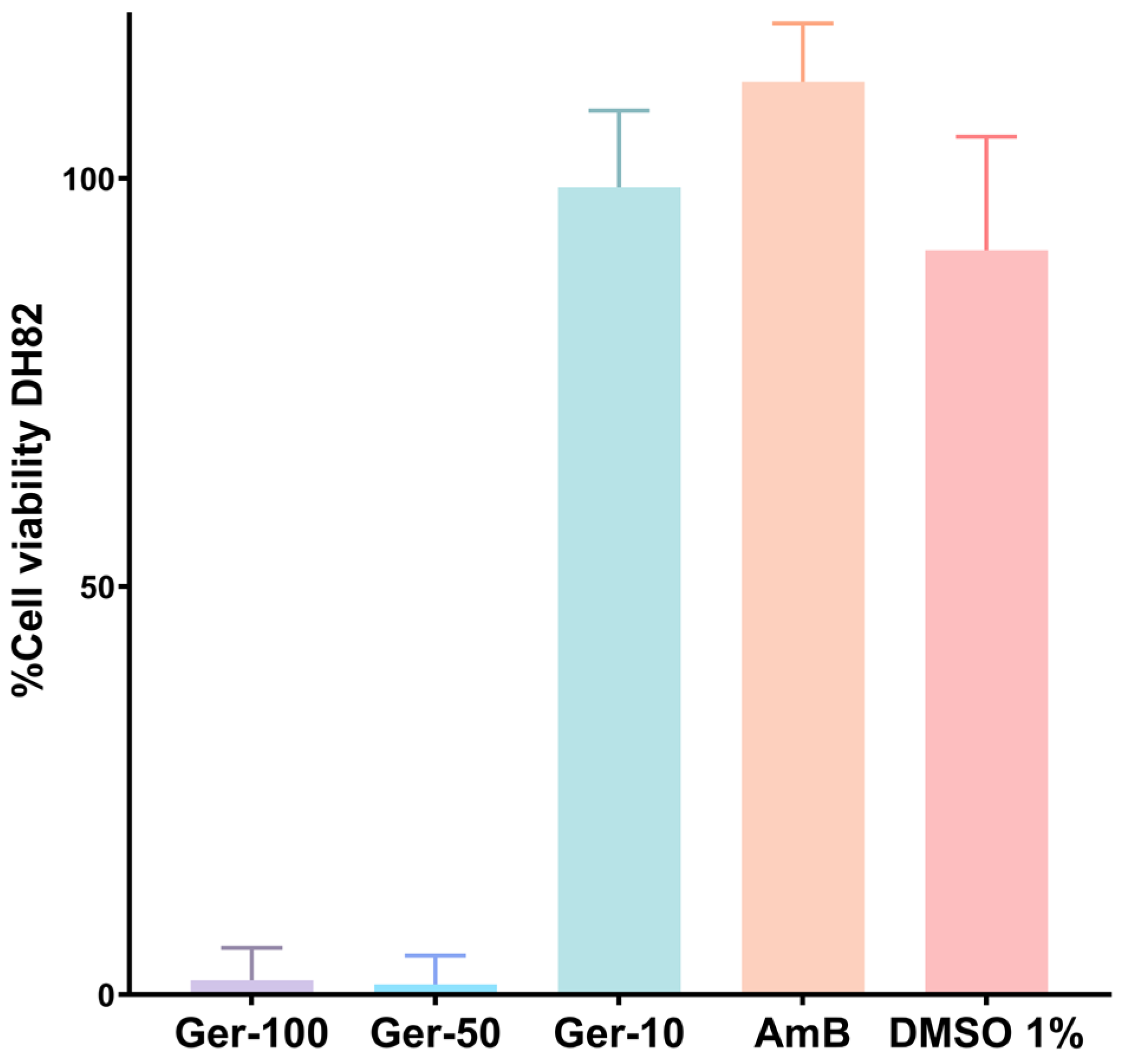

2.4. Antileishmanial Effects of Germacrone on Intracellular Amastigotes

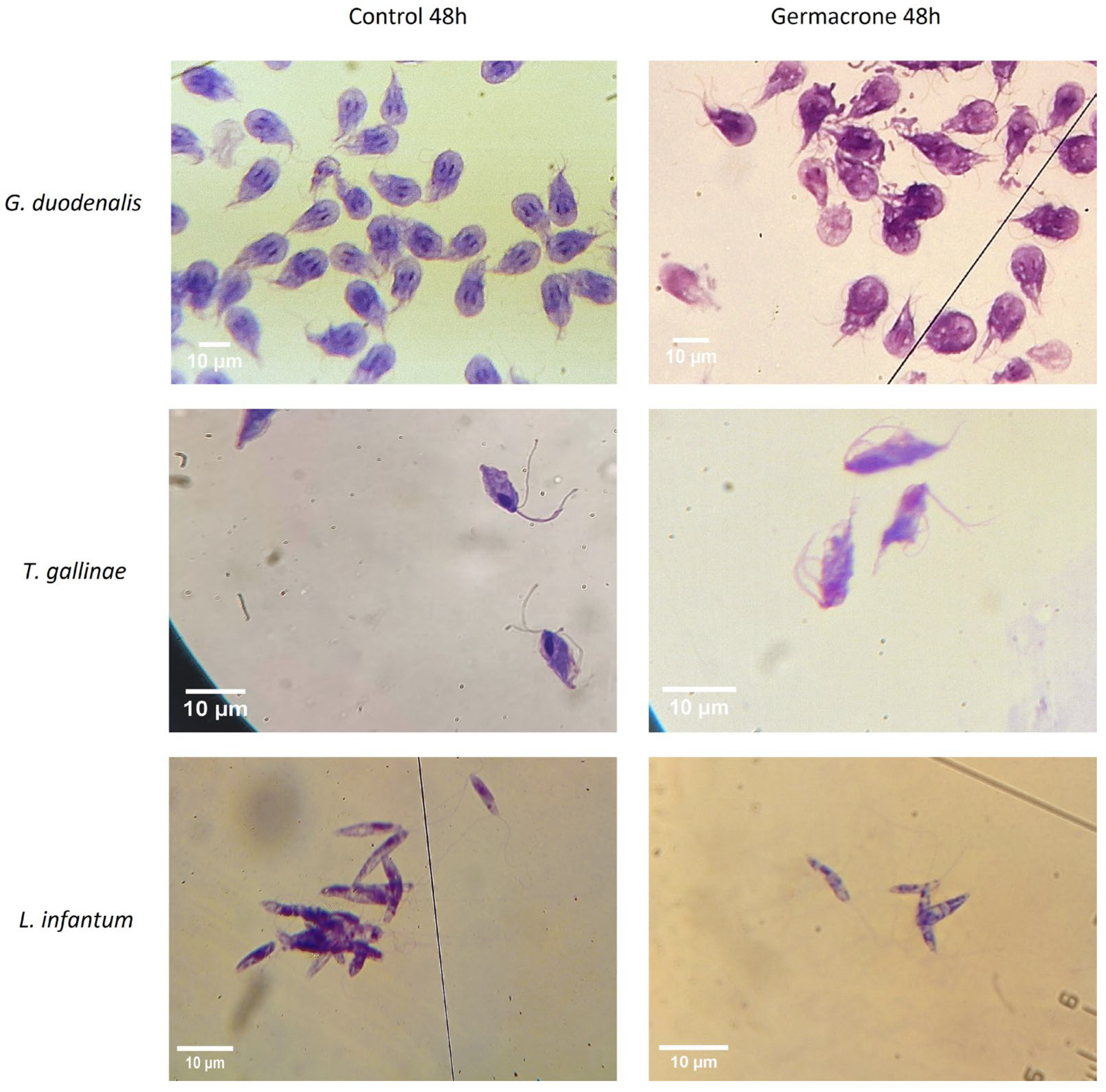

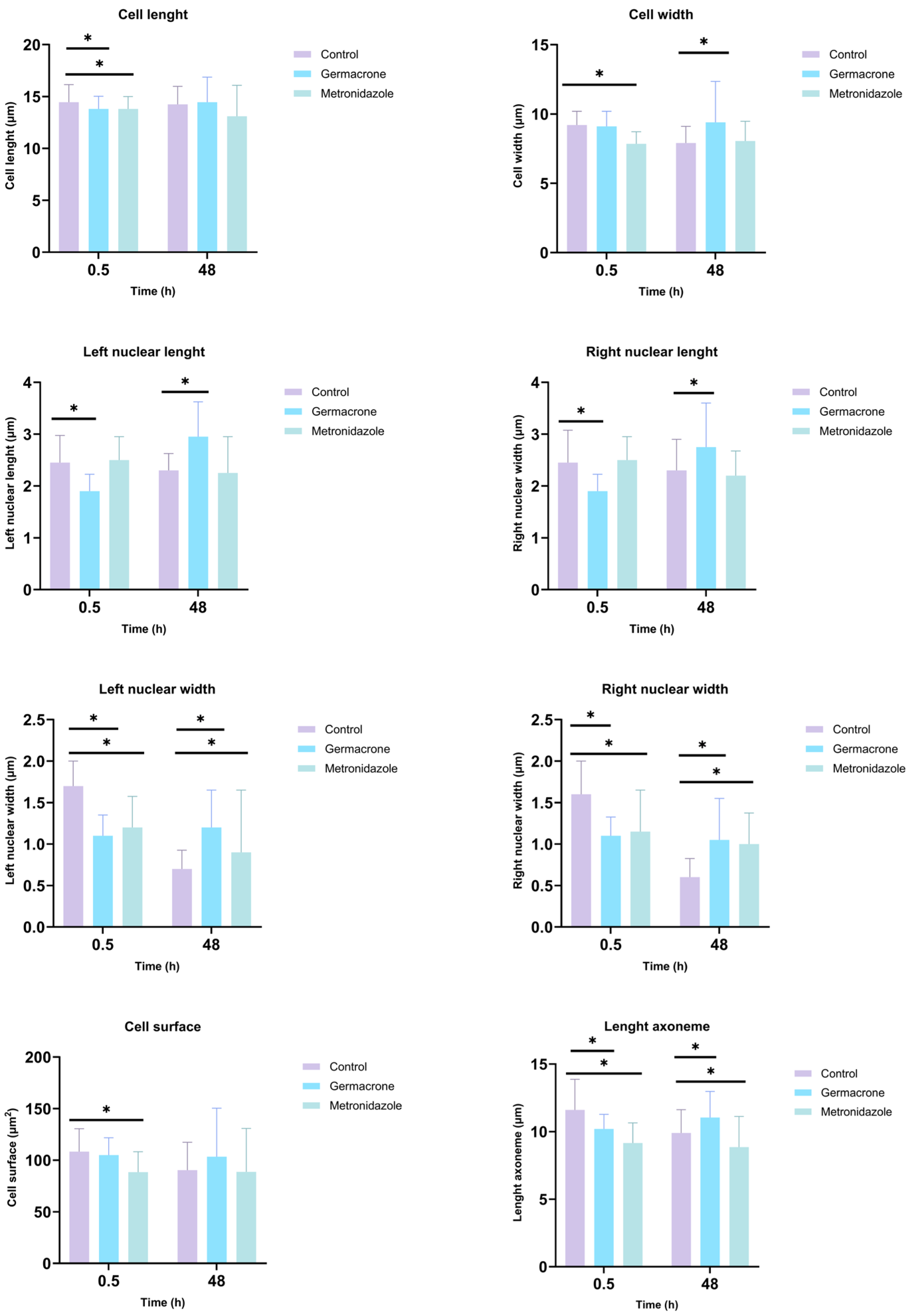

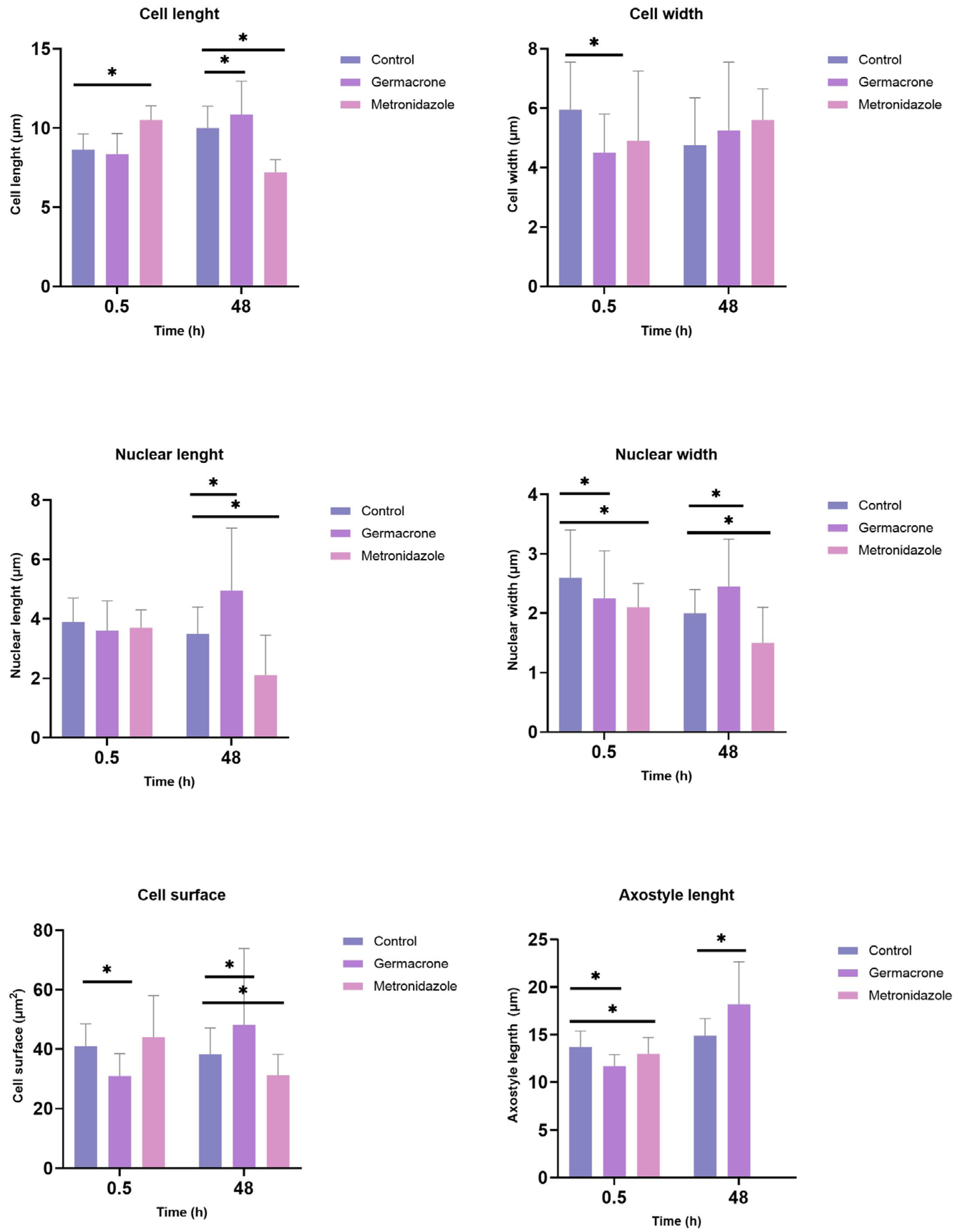

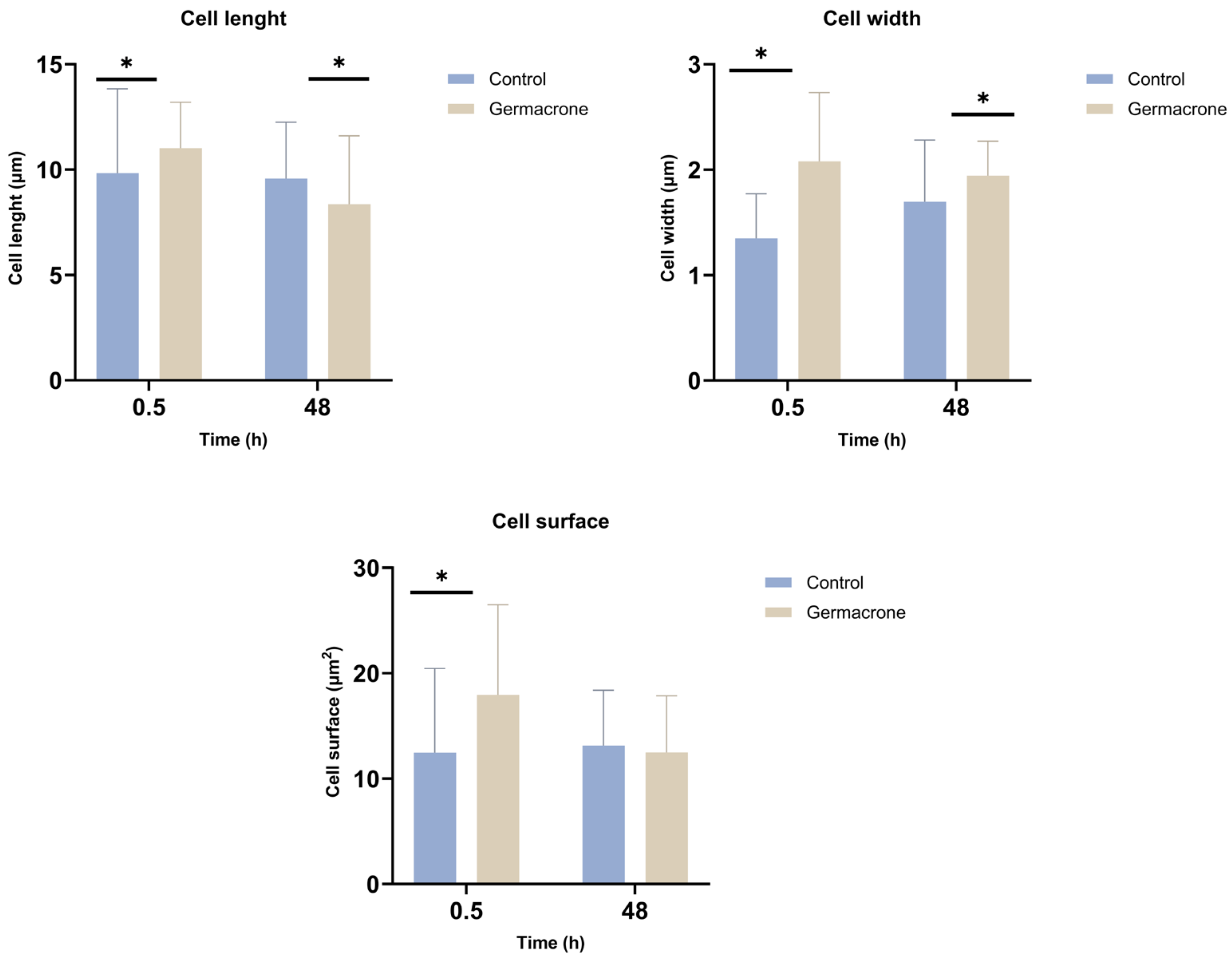

2.5. Morphological Evaluation of the Anti-Protozoan Effects of Germacrone

2.5.1. Giardia duodenalis

2.5.2. Trichomonas gallinae

2.5.3. Leishmania infantum

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

4.2. Essential Oils

4.3. Analysis

4.4. Compounds

4.5. Evaluation of Antiparasitic Effects of G. macrorrhizum Extracts and Main Components on Extracellular Protozoa

4.6. Evaluation of Antileishmanial Effects of Germacrone on Intracellular Amastigotes

4.6.1. Macrophages

4.6.2. Cytotoxicity of Germacrone on Mammalian Cells

4.6.3. Infection Index of Macrophages

4.7. Cytotoxicity of Pure Compounds

4.8. Morphological Evaluation of the Anti-Protozoan Effects

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AG | anti-Giardia |

| AL | anti-Leishmania |

| AmB | Amphotericin B |

| AT | anti-Trichomonas |

| CC50 | 50% cytotoxicity concentration |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium |

| EOs | Essential Oils |

| EOAP | Essential Oils from aerial parts |

| EOF | Essential Oils from flowers |

| FBS | fetal bovine serum |

| GC-MS | Gas Chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| IC50 | Half Maximal Inhibitory Concentration |

| Met | Metronidazoles |

| PBS | phosphate-buffered saline |

References

- Menezes, S.A.; Tasca, T. Essential Oils and Terpenic Compounds as Potential Hits for Drugs against Amitochondriate Protists. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramanik, P.K.; Alam, M.N.; Roy Chowdhury, D.; Chakraborti, T. Drug Resistance in Protozoan Parasites: An Incessant Wrestle for Survival. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2019, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasidharan, S.; Saudagar, P. Leishmaniasis: Where Are We and Where Are We Heading? Parasitol. Res. 2021, 120, 1541–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Leishmaniasis. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/gho-ntd-leishmaniasis (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Cernikova, L.; Faso, C.; Hehl, A.B. Five Facts about Giardia lamblia. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argüello-García, R.; Leitsch, D.; Skinner-Adams, T.; Ortega-Pierres, M.G. Drug Resistance in Giardia: Mechanisms and Alternative Treatments for Giardiasis. Adv. Parasitol. 2020, 107, 201–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.; Bilic, I.; Liebhart, D.; Hess, M. Trichomonads in Birds—A Review. Parasitology 2014, 141, 733–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Comission. Commission Regulation (EC) No 1798/95 of 25 July 1995 Amending Annex IV to Council Regulation (EEC) No 2377/90 Laying down a Community Procedure for the Establishment of Maximum Residue Limits of Veterinary Medicinal Products in Foodstuffs of Animal Origin. Off. J. Eur. Union 1995, L174, 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gervazoni, L.F.O.; Barcellos, G.B.; Ferreira-Paes, T.; Almeida-Amaral, E.E. Use of Natural Products in Leishmaniasis Chemotherapy: An Overview. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 579891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasov, A.G.; Zotchev, S.B.; Dirsch, V.M.; Orhan, I.E.; Banach, M.; Rollinger, J.M.; Barreca, D.; Weckwerth, W.; Bauer, R.; Bayer, E.A.; et al. Natural Products in Drug Discovery: Advances and Opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasim, N.; Sandeep, I.S.; Mohanty, S. Plant-Derived Natural Products for Drug Discovery: Current Approaches and Prospects. Nucleus 2022, 65, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aedo, C.; Garmendia, F.M.; Pando, F. World Checklist of Geranium L. (GERANIACEAE). An. Jard. Bot. Madr. 1998, 56, 211–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Rocha, J.; Barrero, A.F.; Burillo, J.; Olmeda, A.S.; González-Coloma, A. Valorization of Essential Oils from Two Populations (Wild and Commercial) of Geranium macrorrhizum L. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 116, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulović, N.; Dekić, M.; Stojanović-Radić, Z. Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of the Volatile Oils of Geranium sanguineum L. and G. robertianum L. (Geraniaceae). Med. Chem. Res. 2012, 21, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miliauskas, G.; Van Beek, T.A.; Venskutonis, P.R.; Linssen, J.P.H.; De Waard, P. Antioxidative Activity of Geranium macrorrhizum. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2004, 218, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzanova, M.T.; Grozeva, N.H.; Gerdzhikova, M.A.; Todorova, M.H. Composition and Antioxidant Potential of Essential Oil of Geranium macrorrhizum L. from Different Regions of Bulgaria. Bulg. Chem. Commun. 2024, 56, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, B.A.; Iqbal, J.; Ahmad, R.; Zia, L.; Kanwal, S.; Mahmood, T.; Wang, C.; Chen, J.T. Bioactivities of Geranium wallichianum Leaf Extracts Conjugated with Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada, F.; Cervantes-Martínez, J.A.; Yépez-Mulia, L. In Vitro Antiprotozoal Activity from the Roots of Geranium mexicanum and Its Constituents on Entamoeba Histolytica and Giardia Lamblia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 98, 191–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada, F.; Yépez-Mulia, L.; Tapia-Contreras, A. Effect of Mexican Medicinal Plant Used to Treat Trichomoniasis on Trichomonas vaginalis Trophozoites. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 113, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooriyan, S.; Dehghani Bidgoli, R.; Tunç, Y. Enhancing Medicinal Plant Yield Through Optimization in Greenhouses and Controlled Environments: A Review. Greenh. Plant Prod. J. 2025, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, I.S.A.; Koko, W.S.; Khan, T.A.; Schobert, R.; Biersack, B. Antiparasitic Activity of Fluorophenyl-Substituted Pyrimido[1,2-a]Benzimidazoles. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, S.M.; Pino, N.; Stashenko, E.E.; Martínez, J.R.; Escobar, P. Antiprotozoal Activity of Essential Oils Derived from Piper spp. Grown in Colombia. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2013, 25, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailén, M.; Díaz-Castellanos, I.; Azami-Conesa, I.; Alonso Fernández, S.; Martínez-Díaz, R.A.; Navarro-Rocha, J.; Gómez-Muñoz, M.T.; González-Coloma, A. Anti-Trichomonas gallinae Activity of Essential Oils and Main Compounds from Lamiaceae and Asteraceae Plants. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 981763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilić, M.D.; Marčetić, M.D.; Zlatković, B.K.; Lakušić, B.S.; Kovačević, N.N.; Drobac, M.M. Chemical Composition of Volatiles of Eight Geranium L. Species from Vlasina Plateau (South Eastern Serbia). Chem. Biodivers. 2020, 17, e1900544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada, F.; Meckes, M.; Cedillo-Rivera, R.; Tapia-Contreras, A.; Mata, R. Screening of Mexican Medicinal Plants for Antiprotozoal Activity. Pharm. Biol. 1998, 36, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, H.; Han, J.H.; Hong, M.; Fitriana, F.; Syahada, J.H.; Lee, W.J.; Mazigo, E.; Louis, J.M.; Nguyen, V.T.; Cha, S.H.; et al. Ellagic Acid from Geranium thunbergii and Antimalarial Activity of Korean Medicinal Plants. Molecules 2025, 30, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, J.N.; Gomez, M.C.V.; Rolón, M.; Coronel, C.; Almeida-Bezerra, J.W.; Fidelis, K.R.; Menezes, S.A.d.; Cruz, R.P.d.; Duarte, A.E.; Ribeiro, P.R.V.; et al. Chemical Composition, Evaluation of Antiparasitary and Cytotoxic Activity of the Essential Oil of Psidium brownianum MART EX. DC. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2022, 39, 102247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, V.P.; Alves, C.C.F.; Miranda, M.L.D.; Bretanha, L.C.; Balleste, M.P.; Micke, G.A.; Silveira, E.V.; Martins, C.H.G.; Ambrosio, M.A.L.V.; de Souza Silva, T.; et al. Chemical Composition and in Vitro Leishmanicidal, Antibacterial and Cytotoxic Activities of Essential Oils of the Myrtaceae Family Occurring in the Cerrado Biome. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 123, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima Nunes, T.A.; Santos, M.M.; de Oliveira, M.S.; de Sousa, J.M.S.; Rodrigues, R.R.L.; Sousa, P.S.d.A.; de Araújo, A.R.; Pereira, A.C.T.d.C.; Ferreira, G.P.; Rocha, J.A.; et al. Curzerene Antileishmania Activity: Effects on Leishmania amazonensis and Possible Action Mechanisms. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 100, 108130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elso, O.G.; Clavin, M.; Hernandez, N.; Sgarlata, T.; Bach, H.; Catalan, C.A.N.; Aguilera, E.; Alvarez, G.; Sülsen, V.P. Antiprotozoal Compounds from Urolepis hecatantha (Asteraceae). Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2021, 2021, 6622894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethencourt-Estrella, C.J.; Nocchi, N.; López-Arencibia, A.; Nicolás-Hernández, D.S.; Souto, M.L.; Suárez-Gómez, B.; Díaz-Marrero, A.R.; Fernández, J.J.; Lorenzo-Morales, J.; Piñero, J.E. Antikinetoplastid Activity of Sesquiterpenes Isolated from the Zoanthid palythoa Aff. Clavata. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.C.J.; Carloto, A.C.M.; Gonçalves, M.D.; Concato, V.M.; Detoni, M.B.; Santos, Y.M.d.; Cruz, E.M.S.; Madureira, M.B.; Nunes, A.P.; Pires, M.F.M.K.; et al. Exploring the Leishmanicidal Potential of Terpenoids: A Comprehensive Review on Mechanisms of Cell Death. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1260448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwaka, S.; Hudson, A. Innovative Lead Discovery Strategies for Tropical Diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006, 5, 941–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, A.; Rasul, A.; Kanwal, N.; Hussain, G.; Shah, M.A.; Sarfraz, I.; Ishfaq, R.; Batool, R.; Rukhsar, F.; Adem, Ş. Germacrone: A Potent Secondary Metabolite with Therapeutic Potential in Metabolic Diseases, Cancer and Viral Infections. Curr. Drug Metab. 2020, 21, 1079–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Zhai, X.; Su, J.; Ye, R.; Zheng, Y.; Su, S. Antiviral Activity of Germacrone against Pseudorabies Virus in Vitro. Pathogens 2019, 8, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Bai, X.; Cui, T.; Zhou, H.; Chen, Y.; Xie, J.; Shi, Q.; Wang, H.; Zhang, G. In Vitro Antiviral Activity of Germacrone Against Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus. Curr. Microbiol. 2016, 73, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galisteo Pretel, A.; Pérez Del Pulgar, H.; Guerrero de León, E.; López-Pérez, J.L.; Olmeda, A.S.; Gonzalez-Coloma, A.; Barrero, A.F.; Quílez Del Moral, J.F. Germacrone Derivatives as New Insecticidal and Acaricidal Compounds: A Structure-Activity Relations. Molecules 2019, 24, 2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Tang, X.; Yang, J.; Pan, C.; Liu, C.; Han, J.; Li, C.; Yi, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. In Vitro Inhibition of Six Active Sesquiterpenoids in Zedoary Turmeric Oil on Human Liver Cytochrome P450 Enzymes. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 322, 117588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zárybnický, T.; Matoušková, P.; Skálová, L.; Boušová, I. The Hepatotoxicity of Alantolactone and Germacrone: Their Influence on Cholesterol and Lipid Metabolism in Differentiated HepaRG Cells. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou El-Leel, O.F.; AbouEl-Leil, E.F.; Aly, A.A. Evaluation of in Vitro-Geranium (Pelargonium graveolens) Plants Affected by Irradiation and Chemical Mutagens. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 7170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

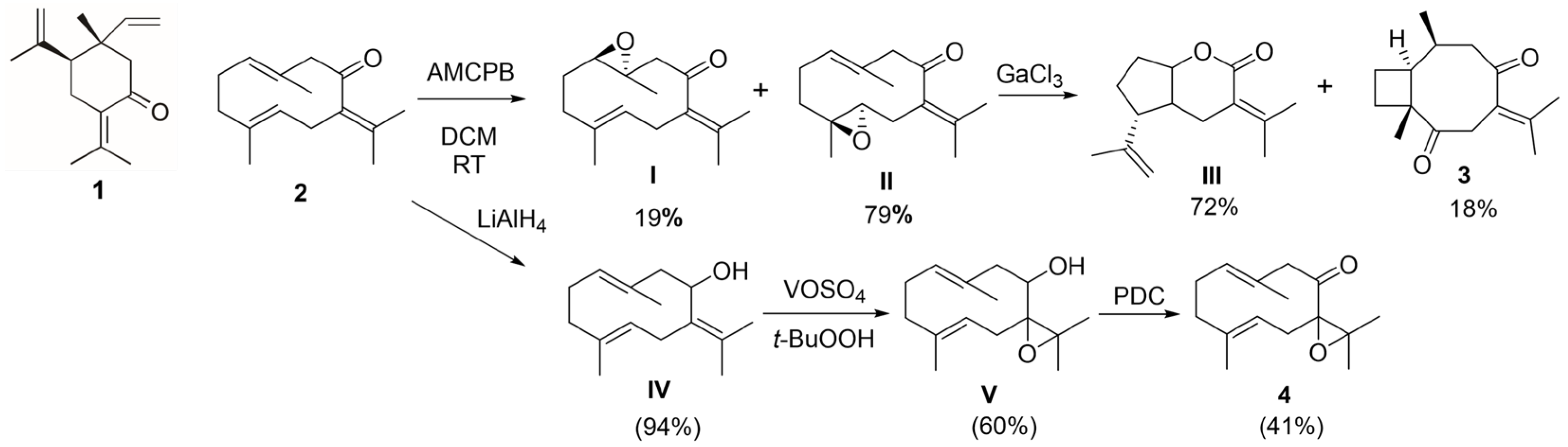

- Barrero, A.F.; Mar Herrador, M.; Arteaga, P.; Catalán, J.V. Germacrone: Occurrence, Synthesis, Chemical Transformations and Biological Properties. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2008, 3, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, E.; Calzada, F.; López-Huerta, F.A.; Yépez-Mulia, L.; Ortega, A. Antiprotozoal Activity of 8-Acyl and 8-Alkyl Incomptine A Analogs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 3260–3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Chávez, J.L.; Rufino-González, Y.; Ponce-Macotela, M.; Delgado, G. In Vitro Activity of ‘Mexican Arnica’ Heterotheca inuloides Cass Natural Products and Some Derivatives against Giardia intestinalis. Parasitology 2015, 142, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada, F.; Cedillo-Rivera, R.; Mata, R. Antiprotozoal Activity of the Constituents of Conyza filaginoides. J. Nat. Prod. 2001, 64, 671–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.W.; Wright, C.W.; Cai, Y.; Yang, S.L.; Phillipson, J.D.; Kirby, G.C.; Warhurst, D.C. Antiprotozoal Activities of Centipeda minima. Phytother. Res. 1994, 8, 436–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passreiter, C.M.; Sandoval-Ramirez, J.; Wright, C.W. Sesquiterpene lactones from Neurolaena oaxacana. J. Nat. Prod. 1999, 62, 1093–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivasenko, S.A.; Edil’baeva, T.T.; Kulyyasov, A.T.; Atazhanova, G.A.; Drab, A.I.; Turdybekov, K.M.; Raldugin, V.A.; Adekenov, S.M. Structure and Biological Activity of α-Santonin Chloro-Derivatives. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2006, 42, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.H.; Liu, K.Y.; Mei, J.; Gao, X.Z. In Vitro Anti-Trichomonas vaginalis Effects of a Mixture of Dihydroartemisinin and Metronidazole. Zhongguo Ji Sheng Chong Xue Yu Ji Sheng Chong Bing Za Zhi 2010, 28, 416–421. [Google Scholar]

- Cheikh-Ali, Z.; Adiko, M.; Bouttier, S.; Bories, C.; Okpekon, T.; Poupon, E.; Champy, P. Composition, and Antimicrobial and Remarkable Antiprotozoal Activities of the Essential Oil of Rhizomes of Aframomum sceptrum K. Schum. (Zingiberaceae). Chem. Biodivers. 2011, 8, 658–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, T.; Sardar, S.K.; Ghosal, A.; Prasad, A.; Nakano, Y.S.; Dutta, S.; Nozaki, T.; Ganguly, S. Andrographolide Induced Cytotoxicity and Cell Cycle Arrest in Giardia Trophozoites. Exp. Parasitol. 2024, 262, 108773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argüello-García, R.; Calzada, F.; Chávez-Munguía, B.; Matus-Meza, A.S.; Bautista, E.; Barbosa, E.; Velazquez, C.; Hernández-Caballero, M.E.; Ordoñez-Razo, R.M.; Velázquez-Domínguez, J.A. Linearolactone Induces Necrotic-like Death in Giardia intestinalis Trophozoites: Prediction of a Likely Target. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, P.A.; Jimenez-Ortiz, V.; Tonn, C.; Giordano, O.; Galanti, N.; Sosa, M.A. Natural Sesquiterpene Lactones Are Active against Leishmania mexicana. J. Parasitol. 2008, 94, 1143–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corpas-López, V.; Merino-Espinosa, G.; Díaz-Sáez, V.; Morillas-Márquez, F.; Navarro-Moll, M.C.; Martín-Sánchez, J. The Sesquiterpene (−)-α-Bisabolol Is Active against the Causative Agents of Old World Cutaneous Leishmaniasis through the Induction of Mitochondrial-Dependent Apoptosis. Apoptosis 2016, 21, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima Nunes, T.A.; Costa, L.H.; De Sousa, J.M.S.; De Souza, V.M.R.; Rodrigues, R.R.L.; Val, M.d.C.A.; Pereira, A.C.T.d.C.; Ferreira, G.P.; Da Silva, M.V.; Da Costa, J.M.A.R.; et al. Eugenia piauhiensis Vellaff. Essential Oil and γ-Elemene Its Major Constituent Exhibit Antileishmanial Activity, Promoting Cell Membrane Damage and in Vitro Immunomodulation. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2021, 339, 109429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailén, M.; Illescas, C.; Quijada, M.; Martínez-Díaz, R.A.; Ochoa, E.; Gómez-Muñoz, M.T.; Navarro-Rocha, J.; González-Coloma, A. Anti-Trypanosomatidae Activity of Essential Oils and Their Main Components from Selected Medicinal Plants. Molecules 2023, 28, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keister, D.B. Axenic culture of Giardia lamblia in TYI-S-33 medium supplemented with bile. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1983, 77, 487–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Cotrina, J.; Iniesta, V.; Belinchón-Lorenzo, S.; Muñoz-Madrid, R.; Serrano, F.; Parejo, J.C.; Gómez-Gordo, L.; Soto, M.; Alonso, C.; Gómez-Nieto, L.C. Experimental Model for Reproduction of Canine Visceral Leishmaniosis by Leishmania infantum. Vet. Parasitol. 2013, 192, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo Díaz, J.E.; Gómez Muñoz, M.T.; Martínez-Díaz, R.A.; González-Coloma, A. Adaptación del ensayo colorimétrico del MTT para la evaluación de la actividad frente a Giardia duodenalis. Rev. Argent. Parasitol. 2023, 12, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Bernal, G.; Jiménez, M.; Molina, R.; Ordóñez-Gutiérrez, L.; Martínez-Rodrigo, A.; Mas, A.; Cutuli, M.T.; Carrión, J. Characterisation of the Ex Vivo Virulence of Leishmania infantum Isolates from Phlebotomus perniciosus from an Outbreak of Human Leishmaniosis in Madrid, Spain. Parasit. Vectors 2014, 7, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| G. macrorrhizum | G. duodenalis a | L. infantum a | T. gallinae a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 | R2 | IC50 | R2 | IC50 | R2 | ||

| EOs | EOAP | >500 | - | 69.6 (62.5–77.4) | 91.3 | 120.4 (108.0–134.3) | 94.7 |

| EOF | >300 | - | >800 | - | 67.2 (63.1–71.6) | 97.1 | |

| RT | RI | % Relative Abundance | Compound | Class | % Relative Abundance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EOAP | EOF | EOAP | EOF | ||||

| 13.89 | 1369 | 3.05 | 1.11 | g-elemene | Non oxygenated sesquiterpenes | 6.77 | 1.11 |

| 14.92 | 1485 | 3.72 | - | (+)-cuparene | |||

| 17.49 | 1609 | 32.64 | 42.07 | β-elemenone (1) | Oxygenated sesquiterpenes | 73.4 | 78.9 |

| 18.53 | 3.74 | 3.23 | 70/121/93/42/67/107/41/95/79/81 | - | |||

| 19.36 | 1704 | 40.72 | 36.85 | germacrone (2) | Oxygenated sesquiterpenes | ||

| Compound | Vero Cells | L. infantum (pm) | G. duodenalis | T. gallinae | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC50 (µg/mL) a | IC50 (µg/mL) b | R2 | SI c | IC50 (µg/mL) b | R2 | SI c | IC50 (µg/mL) b | R2 | SI c | |

| 1 (β-elemenone) | >100 | >100 | - | 1.0 | >100 | - | 1 | >100 | - | 1.0 |

| 2 (germacrone) | ≈100 | 37.5 (33.6–41.9) | 91.1 | 2.7 | 55.2 (48.2–63.2) | 77.6 | 1.8 | 45.8 (37.2–56.3) | 77.4 | 2.2 |

| 3 | >100 | 35.5 (31.2–40.4) | 92.1 | 2.8 | >100 | - | 1 | >100 | - | 1.0 |

| 4 | >100 | 88.8 (62.6–125.9) | 78.0 | 1.1 | >100 | - | 1 | 51.6 (48.6–54.8) | 96.2 | 1.9 |

| AmB | 7.11 [21] | 0.01 [22] | - | 711 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Met | >100 | - | - | - | 4.4 (3.5–5.5) | 96.1 | 22.7 | 1.0 (0.8–1.1) [23] | - | 100 |

| % Infected Cells | nº Amastigotes/Infected Cell | Infection Index | |

|---|---|---|---|

| control of infection | 42.8 ± 6.8 | 3.5 ± 1.8 | 152.1 ± 29.4 |

| DMSO 1% | 46.9 ± 6.9 | 2.7 ± 1.4 | 126.6 ± 4.9 |

| AmB (1 µg/mL) | 6.4 ± 3.7 * | 1.4 ± 0.7 * | 8.9 ± 0.0 * |

| Germacrone (2) 10 µg/mL | 25.9 ± 8.3 * | 2.4 ± 1.1 | 61.0 ± 9.4 * |

| Germacrone (2) 50 µg/mL | dead cells | dead cells | dead cells |

| Germacrone (2) 100 µg/mL | dead cells | dead cells | dead cells |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Marcos-Herraiz, S.; Irisarri-Gutiérrez, M.J.; Carrión, J.; Azami Conesa, I.; Suárez Lombao, R.; Navarro-Rocha, J.; del Moral, J.F.Q.; Fernández Barrero, A.; Ochoa Larrigan, E.; González-Coloma, A.; et al. Antiprotozoal Potential of Cultivated Geranium macrorrhizum Against Giardia duodenalis, Trichomonas gallinae and Leishmania infantum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021125

Marcos-Herraiz S, Irisarri-Gutiérrez MJ, Carrión J, Azami Conesa I, Suárez Lombao R, Navarro-Rocha J, del Moral JFQ, Fernández Barrero A, Ochoa Larrigan E, González-Coloma A, et al. Antiprotozoal Potential of Cultivated Geranium macrorrhizum Against Giardia duodenalis, Trichomonas gallinae and Leishmania infantum. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021125

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarcos-Herraiz, Sara, María José Irisarri-Gutiérrez, Javier Carrión, Iris Azami Conesa, Rodrigo Suárez Lombao, Juliana Navarro-Rocha, Jose Francisco Quilez del Moral, Alejandro Fernández Barrero, Eneko Ochoa Larrigan, Azucena González-Coloma, and et al. 2026. "Antiprotozoal Potential of Cultivated Geranium macrorrhizum Against Giardia duodenalis, Trichomonas gallinae and Leishmania infantum" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021125

APA StyleMarcos-Herraiz, S., Irisarri-Gutiérrez, M. J., Carrión, J., Azami Conesa, I., Suárez Lombao, R., Navarro-Rocha, J., del Moral, J. F. Q., Fernández Barrero, A., Ochoa Larrigan, E., González-Coloma, A., Gómez-Muñoz, M. T., & Bailén, M. (2026). Antiprotozoal Potential of Cultivated Geranium macrorrhizum Against Giardia duodenalis, Trichomonas gallinae and Leishmania infantum. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021125